Research indicates that fads and fashions in business techniques typically have latency periods during which the techniques have little popularity (Abrahamson and Eisenman, 2008). Latency may give way to sudden upswings in techniques’ popularity followed by equally sudden downswings, resulting in waves of diverse amplitudes and durations (Carson, Lanier, Carson, and Guidry, 2000). Some ideas may achieve wide acceptance and popularity; other ideas fail to gain much attention.

Both academic and nonacademic writers had been discussing components of Senge’s TLO for several decades; an emergence and sudden surge in popularity could have occurred earlier. They did not. Senge’s book could have been yet another incremental contribution to a continuing latency period. It was not. Instead, Senge brought TLO to prominence. Why Senge? Why his book? Why in 1990?

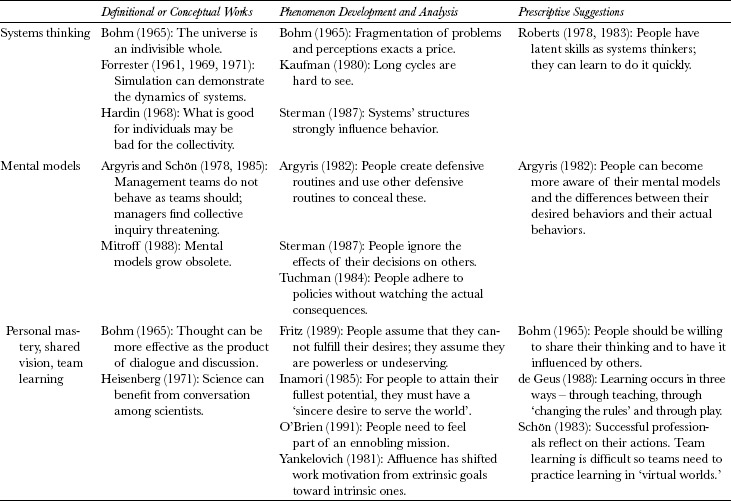

TLO and its five component disciplines build on a wide range of prior conceptual developments. Predecessor thinking concerns organizational learning, organizational rigidity, learning systems, systems thinking, and even prior discussions of similarly described ‘learning organizations.’ Senge devoted large portions of The Fifth Discipline to the ideas of other people. Table 11.1 shows the antecedents on whom Senge relied most strongly; they include both academics and practitioners.

Table 11.1 Antecedents Senge acknowledged as important

Although Senge gave credit to the works listed in Table 11.1, he did not mention much of the research that had preceded his book. Even without attribution, current knowledge builds on prior knowledge. Sometimes similar ideas develop in different camps from a common pool of information, then proceed along different trajectories. Invention races and first-to-invent claims made by individuals in different parts of the world occur often. Senge’s TLO draws from a wide range of prior knowledge concerning systems and organizational learning. Many other thinkers were on tangent paths. For instance, Senge did not report that, fifteen years earlier, Hedberg, Nystrom, and Starbuck (1976: 43) had written about how to keep organizations from rigidifying over time and how to foster continuing development. They argued, ‘Designs can themselves be conceived as processes—as generators of dynamic sequences of solutions, in which attempted solutions induce new solutions and attempted designs trigger new designs.’

Academic studies of organizational learning

As early as 1936, engineers and economists noticed that the costs of producing aircraft grew less as workers produced more aircraft (Argote, 1999). By the early 1950s, academic economists and management scholars were debating the possible influence of evolutionary selection on decision making in populations of business firms (Salgado, Starbuck, and Mezias, 2002). A decade later, Cyert and March (1963) wrote about adaptive learning by individual organizations. They characterized organizational learning as adapting decision rules to circumstances, changing goals and forecasts to reflect experience and updated perceptions, modifying goals to make them more realistic, and searching where previous searches have brought success. Such ideas have subsequently spawned many research studies and generated considerable debate. These studies indicate that organizational learning is deceptively treacherous and very likely to disappoint the learners.

Research studies indicate that the efforts of individual organizations to adapt to their environments are generally inadequate and frequently erroneous. Lessons that prove valuable in the short run tend to prove harmful in the long run (Hedberg et al., 1976). Unpredictable environmental changes may reward organizations that have acted incompetently or ineffectively (Starbuck and Pant, 1996). Intra-organizational politics and careerism may suppress evidence of poor performance and create false evidence of success (Baumard and Starbuck, 2005). Because organizations imitate each other, gains that organizations make vis-à-vis their competitors disappear rather rapidly (Simon and Bonini, 1958). Thus, some researchers have pursued the hypothesis that organizational learning is primarily a population-level phenomenon: evolutionary variation and selection might change the kinds of organizations that exist even if individual organizations change very little. However, over a decade of empirical studies showed that changes in organizational populations look very like random walks (Carroll, 1983; Levinthal, 1991). After more than fifty years of thought and study about organizational learning, March (2010: 114) surmised: ‘Much of organizational and managerial life will produce vividly compelling experiences from which individuals and organizations will learn with considerable confidence, but the lessons they learn are likely to be incomplete, superstitious, self-confirming, or mythic.’

Nonacademic writing about organizational learning

Some of the people who have been working to facilitate organizational learning give credit to Revans, who wrote about ‘The enterprise as a learning system’ (1982). In parallel with Bohm, Argyris, and Schön, on whom Senge relies heavily, Revans argued that organizations should not rely on ‘experts’ for advice and that groups of organization members should discuss their own actions and experiences in a process he called Action Learning.

At least two authors used the exact term ‘the learning organization’ before Senge did, and David Korten (1980) used it a full decade earlier. Korten described five development projects in the Third World, and then argued that such projects should not adhere to plans that were designed top-down but should develop bottom-up through participation by people who understand events at first-hand. There will always be errors, and a learning organization should welcome evidence about errors as guidance about how to perform better. A learning organization also involves local people, takes advantage of what they know, and uses resources that are readily available. A learning organization integrates research, planning, and implementation. However, Korten was clearly talking about development projects that had specific goals and somewhat temporary lifespans, rather than learning that might go on indefinitely.

In a book titled The Learning Organization, Bob Garratt (1987) argued that business organizations typically have too little open discussion of issues, with one result being too little reflection about policies and strategies, and another result being too little information input from business environments. Garratt saw organizational learning as being the special responsibility of senior managers, and he proposed that senior executives ought to devote more effort to their personal learning and they should try to guide their organizations’ continuing development.

In a third work, titled The Learning Company, Pedler, Burgoyne, and Boydell (1988) sought to identify properties of ‘an organization that facilitates the learning of all its members and consciously transforms itself and its context.’ They pointed to eleven properties that would enable such learning. These properties included strategizing as a learning process, wide participation by organization members and stakeholders, a culture that encourages continuous learning, and helpful accounting and information systems.

Clearly, both the term ‘the learning organization’ and the ideas echoed in The Fifth Discipline were well known in the 1980s, especially the late 1980s. Yet, it was Senge’s interpretation of TLO that caught on and began to spread (Jackson, 2000).