8 Reward Your Consumer

Putting It All Together

Eric Barnes’ wife, Stacy, was the first to tell him that his habit of taking an old Gatorade bottle filled with water when he went running was a bad idea. “It’s a bacteria trap,” she warned, “and you don’t clean it regularly. Pretty gross.” Barnes quickly Googled Stacy’s claim and was shocked to learn how fast bacteria began to form. Eager to find an alternative, he visited several sports stores in search of a reusable water bottle and came back empty-handed. All the choices at the time seemed cheap and flimsy or more suited to a camping expedition than to every-day life. However, Eric had never used bottled water before. He didn’t feel right about the environmental impact of the shipping and that most empties weren’t recycled.

Because Eric had been involved in several entrepreneurial ventures since his days as a work-study student at Princeton, it was only natural that he began to wonder if his conundrum represented an opportunity. He had been reading about companies like Method using design as the basis for reinventing crowded categories such as household products. The spark was lit in his mind: What if he could design a great reusable water bottle? As he discussed the idea with his friend Paul Shustak, a Microsoft executive, Paul too was immediately excited by the idea. They knew that there had to be other people like them who would pay more and help the environment if there were better alternatives available.

Barnes and Shustak continued to research the potential for the water bottle and put together a business plan. When they began to research whom they might collaborate with on the actual design, they spotted BusinessWeek’s latest Best Product Design issue. On the cover was a photo of a neon green RKS Guitar, which had just won an International Design Excellence Award (IDEA). Barnes and Shustak contacted the firm. It was the first conversation in a dialogue that continues today, as the company, KOR Water, that was created continues to grow and expand.1

Greening the Landscape

In many ways, Barnes and Shustak exemplify the changes that are taking place in how companies of all sizes approach innovation. Increasingly, the decisions of entrepreneurs and corporate executives alike are driven by three major priorities:

• Sustainability—The green movement has reached critical mass, and initiatives to address these concerns are permeating every business. Eighty-six percent of the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 has sustainability websites, and some major corporations began to produce dedicated sustainability reports in 2007.2 For most new products, sustainability is a requirement at the outset. Many older offerings are being redesigned or removed to comply with new standards and changing consumer expectations. Incorporating sustainability is complex because standards are evolving, for both companies and consumers.

• Design—As a response to the abundance of choices in the marketplace, design has emerged as the new differentiator. More than ever before, consumers seek out well-designed, attractive products, which are now available in a variety of price points. The lure of design also appears to carry globally. In a survey by the Design Council in the UK, 16 percent of businesses reported that design topped their list of key success factors. In newer and growing businesses, that number rose to 47 percent.3

• Consumer behavior—Although demographic studies and consumer surveys will always be important, business decisions are increasingly driven by data on actual behavior—not incomes. Direct consumer observation today can be easily supplemented by visits to websites and blogs, where attitudes and unedited feedback can be accessed at low cost. The reasons for adoption—and the barriers to adoption—can often be uncovered with greater speed and accuracy using these tools.

As Barnes and Shustak mapped out their initial strategy, they describe what they refer to as the “perfect storm”—a crowded market place, where design could make a difference, an still-nascent backlash against bottled water, and concerns about Bisphenol-A (BPA), a chemical used in many reusable water bottles. From their own experience as well as their research, they knew that these trends were converging and creating a new market opportunity.

For the practice of Psycho-Aesthetics®, the KOR challenge presented the “perfect opportunity.” It was a chance to look at the convergence of behavior, design, and sustainability and question assumptions about markets, consumers, and creative boundaries. The limited budget of KOR’s founders was a test of how well the framework could hold up under intense pressure. It was also a chance to definitively show that individuals could have an impact on the “wicked problems” facing the planet. Design could be the driver that motivated change, to the benefit of the planet and all the stakeholders. It was a chance to start from scratch and rewrite the rules. Could design be used to create not just a product, but also a company and a movement?

Enable Your Stakeholders

Barnes and Shustak brought with them the practical experience of having worked on new product developments in large organizations and were familiar with the process of creating strategy, financial analyses, and market positioning to support new projects. Moreover, both of them had experience with emerging technologies, which involved developing user interfaces and understanding how to drive adoption. Design was something they both had a natural interest in, as well as a clear-cut mission.

Barnes and Shustak came to the project armed with significant market research. Barnes had a clear idea of the market segments he felt were attractive. From his Microsoft days, Shustak knew the persona methodology and many strategic frameworks. Still, they were clear about the benefits of the Psycho-Aesthetics process:

“When you’re as passionate as we were, you really need the structure. You need to be challenged and you need a sanity check. Although we had looked at many different brands that we considered aspirational, you need to have an understanding that goes beyond, ‘Apple—great. Motorola—missed the boat.’ You really need to understand why—from the consumers’ point of view. You can derive insight simply from seeing everything lined up—it makes order out of a complex world. We established a rapport with the design team because of the process. We got a great compass, and more importantly, it was easy to hand that compass off to others as they joined us. “When you’re a new company trying to get the attention of investors and the public, too much text really goes against the grain of a creative environment. There’s a cost to making things too complex—you end up being ignored. If you can show a single picture of over a million discarded water bottles, the point gets across very quickly.”

Through the process of mapping products and personas, the founders and design team realized that people who sought out reusable bottles had many different motivations. Broadening the appeal of the bottle would create a larger market. After an intense process of debating priorities, three pillars were established that became hallmarks of the KOR brand—health, sustainability, and design. These pillars amplified all the elements of the “perfect storm” and provided clarity throughout the development and design process. They would become the standard against which to measure strategies, materials, branding, vendors, and business partnerships going forward.

Map the Future

For KOR, the task of mapping the future meant looking outside of its category for inspiration. High-end liquor and cosmetics were closely studied to see how the bottles supported an image of quality and individual expression. “We spent a lot of time in all kinds of places from wine stores to Sephora (a cosmetics superstore) looking at perfume bottles to see how craftsmanship played a role in the product…in water, the only example that we saw of note was Voss, which was a disposable water bottle.” Voss clearly referenced fashion in the aesthetic of the bottle and gave the consumer a sense of luxury.

The field was wide open, and the founders knew a few things for sure: “We knew that we wanted to innovate in some way; otherwise, what was the point? We really wanted to have some discoverable surprises with the design, even though we weren’t sure what those would be at first.” And Eric was determined that the bottle be a one-handed operation, so that it was easy to use when exercising and pursuing a healthy lifestyle. Those were the non-negotiable items. It had to look great and create a new super-premium category for water bottles.

Though the goals were clear, the process of how to get there was not. Design was important, but as health and sustainability were added, new categories, brands, and causes were mapped to identify where consumers were exchanging ideas on these issues. A person passionate about sustainability may be drawn to very different brands and offerings than a design aficionado. The design team set about assessing the brands, movements, and products that had credibility in all three pillars and narrowing down how to convey quality to all of them. Achieving balance among the three goals was also paramount. Too “designer” risked appearing superficial. Sustainability alone could be judgmental. Health, of course, remained important, but many other bottles were already in use among fitness and sports enthusiasts. It would be most difficult to break into this segment.

Although water was an issue that both KOR and the designers became more passionate about as the project evolved, there were explicit reasons that they chose to focus on the bottle. With so many large, well-funded players researching and addressing water safety, they knew that they could not make much of an impact there. Instead, they could transform water consumption into a new experience and create a platform to raise awareness of the issues surrounding health and sustainability. Using design to drive adoption was also important because of the message that the founders wanted to communicate: “We wanted the KOR brand to be about optimism, not guilt. We were striving to make it as green as possible, but if someone picks it up just because they like how it looks, that’s okay with us. That’s still taking a lot of disposable bottles out of the landfill,” they reasoned.

Personify Your Consumer

When KOR first began, the founders began with the intent of reaching a segment they knew well: the folks who were a lot like them. Barnes and Shustak recall their initial feelings about the water bottle segment: “What if you’re the person who has Kenneth Cole shoes, a Coach bag, and a Blackberry? There was nothing for the segment we like to call the digerati…the urban, global person interested in tech, gadgets, gear, and upwardly mobile career. If you go into a conference room, that backpacker look doesn’t translate….”

In addition to the digerati, KOR also had a few other key personas in mind. There were the Machinists—avid exercisers who worked out primarily in the gym and carried water with them. Mothers, traditionally the stewards of the family’s health, were another category. The final persona it wanted to appeal to was the consumer looking for “meaningful consumption” who might drive a hybrid car even if she could afford a luxury model. This individual would seek out brands such as Patagonia, despite the cost, because the brand values resonated with her own.

The mapping of personas and creating Day-in-the-Life scenarios provided a reality check on assumptions that were implicitly made about all the target consumers. The personas were significantly refined and additional ones were added. Most of the initial personas were upper-income, but further research and mapping revealed that the concerns KOR was addressing had a much wider audience. The view of the consumer was broadened in terms of income, age, and occupation.

It was clear that the greatest impact KOR could have—both in terms of building market share and helping the environment—would be in terms of convincing those consumers currently using bottled water to switch to a reusable bottle. Consumers switching from another brand to KOR were a much smaller market and a secondary concern. Research had revealed that the use of disposable to reusable bottle usage was 50:1. As a small company, it was a matter of necessity to focus on those seeking meaningful consumption and those who enjoyed design. As Barnes summed up, “People want to do better, but they don’t want to do it for less….”

Addressing the issue of sustainability was especially challenging, because of the complexity of consumers and the green movement itself. Standards are still evolving as to what an acceptable carbon footprint is, for example. But it was clear that sustainability was no longer a fringe movement that could be ignored. Piles of plastic water bottles were showing up everywhere, raising the costs of recycling. The public momentum was beginning to build against bottled water but had yet to reach critical mass. The consumers who cared deeply about the issue seemed to apply the mantra of “reduce, reuse, recycle” to all their purchases, even ones that made no environmental claims. Product reviews in a wide variety of categories reflected this. Consider the reviews on Amazon.com for Olay’s 14-day Skin Intervention, a beauty product that consists of 14 small, individually packaged tubes of skin cream. Consumers who loved the product had this to say:

“I would have given this five stars, but this product like most of Olay’s has just a shocking amount of packaging. In this day and age most manufacturers have gotten a clue that this is just unacceptable.

“Another consumer echoes the rave reviews of the product, giving it five stars, but acknowledges the concerns of other reviewers by saying, ‘I’ll recycle extra as penance.’”4

To make matters more complicated, sustainability tended to attract as many people as it repels because of confusing marketing claims and guilt-laden peer interactions. KOR spoke as much about design as sustainability for this very reason: “We wanted to let the consumer know— hey, we’re not perfect. Nobody is. We’re right there in the confessional with you, trying to figure it all out—what we like, what’s good for the planet. There is never any judgment about the reasons why you bought the bottle. We don’t have the ultimate equation….” Making the product attractive to those actively seeking green, health, and design was central to broadening the appeal of the product. The emphasis on celebrities and high fashion also receded as the brand gathered momentum.

Own the Opportunity

As awareness of the environmental impact of bottled water usage grew, the reusable water bottle market began to heat up as generic knock-offs of top brands, such as SIGG, jumped into the fray. The trends of personalization and design (carried over from other segments, such as wine) were becoming prevalent. Bottled-water manufacturers had succeeded in connecting hydration and health in consumer’s minds, and even those rejecting disposable bottles wanted to maintain a healthy level of water consumption.

As the team derived Key Attractors common among the personas, the idea of seeing the water was critical. Glass was not a practical alternative for everyday use, and the available versions of plastic bottles did not convey quality. Seeing the water elevated in the right vessel would also reinforce the idea that water was precious, just as the perfect wine glass is a symbol of craftsmanship and enhances the enjoyment of wine. The team began to look for ways to use plastic to create both ruggedness and elegance in the design.

It was the pillar of health that provided a window to break through the clutter. Looking at websites and chat rooms, Eric and Paul began to notice consumer concerns surfacing about BPA, an additive in many plastics. As Paul recalls, “There was a point in time where you would just see one or two posts on the websites that we visited regularly. But as we started bookmarking articles that we came across, we really started to see a hockey stick type of pattern with the number of concerns, complaints, and links to scientific research. We knew that this issue was going to be big and that we needed to be proactive…so we were interested in alternatives to polycarbonate right away.” The evidence at the time was still being debated, but the concern was real. The team began to look for a plastic that might be BPA-free. However, at the time there were no known alternatives.

Leveraging the strong relationships with Eastman from earlier projects, notably RKS Guitars, the design team received an early, confidential confirmation that a new material was in development. Based on our talks, they opted to engineer it to be BPA-free. Although the team was still working out many details of design and messaging, the decision to wait for the new material was an easy one. It was a matter of upholding the three central values that KOR used to define itself. As the public concern with BPA gathered steam, the dearth of alternatives created a huge opportunity for KOR. The spike in BPA news and restrictions reached critical mass in May/June 2008, just as the KOR ONE was ready to launch.

Work the Design Process

Eric Barnes was unequivocal about the importance of design from the beginning saying, “We knew that if we could think maniacally about how to use design, we could compete against much larger companies. We knew that was the variable that we had to win on.” The design team was already inspired by the cause and the founders. Based on the intense Psycho-Aesthetics work that had been done, they achieved an overall shape and form to work from within three months. The elliptical shape made the bottle easier to carry than the traditional round bottles, and the it could also be carried from the top. The aesthetics represented a huge separation from the outdoorsy feel of what was already in the market, and the team felt confident that it had the ability to become iconic. KOR bottles looked at home in a business meeting, a yoga studio, and a variety of urban settings. It was unexpected but aspirational. Barnes hoped it could be like the Aeron chair, which initially separated people but was ultimately catapulted in popularity when designers and architects embraced it. Though the team was excited about the direction of the design right away, there was more work to be done.

The various design elements of the first KOR ONE water bottle (see Figure 8.1) were:

• Cap—The hinged cap was designed to be easy to operate with one hand and close so securely it wouldn’t leak even if laid flat.

• Tritan material—Eastman’s BPA-free Tritan material provides a safe and durable alternative to traditional materials It also has superior clarity, resembling glass.

• Wide mouth—An extra-wide mouth makes the bottle easy to use from the tap and fridge. It easily accepts full-size ice cubes, and water can be gulped or sipped easily.

• Elliptical shape/handholds at top—These form a “frame” for the water to be showcased and make it easier to carry around and hold.

• Recycling—In keeping with the aim of sustainability, KOR provides a lifetime policy of taking back bottles for proper recycling when (and if) they have gone past their useful life.

• KOR stones—The cap contained a place for an inspirational message and a way to personalize bottles.

© RKS Design

Figure 8.1 The first KOR ONE water bottle

Creating a design that could be operated with one hand that kept the cap tethered to the bottle required trying more than ten different solutions. A cap that screwed onto the bottle could have gone into production far earlier, but the important idea of innovation would have been sacrificed. The team knew that to achieve the desired emotional connection it needed to offer its target personas a better experience. And it knew that the one-handed opening would help create this connection.

As the issue of the cap came to resolution, other ideas had surfaced regarding the appearance and overall feel of the bottle. It was time to look at the personas again, as well as the Key Attractors that were established early on. As the design was held up, the team begun to realize that adding elements might actually make the bottle seem superficial and contrived, thus limiting the audience.

Barnes’ decision on when KOR’s first offering was ready drew on lessons from mythology as well: “At some point, you don’t want to be Icarus flying too close to the sun. There are challenges and trade-offs in reaching too far. As a new company, you also have to have faith that you have to put together a great product, but you’re going to get a second chance. The consumer doesn’t need to know everything that you thought of; they need to see something inspirational. If there are other ideas, you can put them in your pocket.”

Engage Emotionally

The inspiration behind KOR always included the idea of creating a community united by a love of design and concern for the environment and health. The founders saw how the Summer Olympics in 2004 was where people of all different races and ages were beginning to sport the LIVESTRONG wristbands and support a cause. They, too, hoped that their product would spawn the creation of a tribe.

As KOR was looking for a manufacture that would measure up to their SET (Sustainable, Ethical, Transparent) standards, the converging waves of demand (the backlash against bottled water, the power of design in the market, and the BPA issue) continued to build. Then, in the late spring of 2008, the BPA issue reached a tipping point. Canada prohibited the use of plastic containing BPA in baby products, and some cities banned BPA altogether. KOR was still in tooling as one top competitor began to use Tritan material in their bottles. It was a nerve-wracking time. The team was so close; it was frustrating that challenges in manufacturing caused delays. Though it lost the chance to be the first BPA-free reusable water bottle, none of the competitors had the entire package of design, health, and sustainability.

But then KOR hit a roadblock it had failed to anticipate. Like so many small businesses, unanticipated expenses in tooling had emptied its coffers. There was no money left to give the bottle the marketing launch it deserved. It had built a website, but there was the real risk of taking the website live and getting no traffic—the proverbial tree falling in the woods with no one to hear it.

Luckily, the RKS team had recently proven the success of applying the Hero’s Journey to marketing strategy. They’d earlier put out a carefully targeted press release about the Mimique cell phone concept (one of the first concepts designed for Google Android), which became an instant Internet hit. The RKS team knew they could generate this same kind of attention for the KOR ONE. It had a product designed to connect emotionally; it had wonderful photography (taken by Ben Dowdy and Carla Olson of Eastman); and it had the timing to capture the raw power of that perfect storm.

When KOR and Eastman saw the results generated by the Mimique press release, they gave RKS the nod to take the lead. RKS customized a list of key blogs created to fit the audience for KOR’s offering, ensuring that each target persona would be reached. The team compared notes with KOR to make sure the websites that had provided early insight and inspiration for Eric and Paul were included.

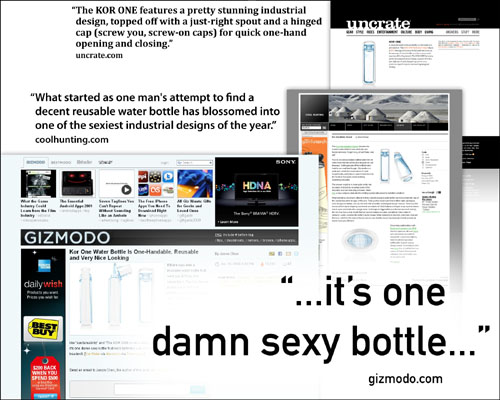

A press release was carefully crafted to ensure that all the emotional touch points of the design were showcased. In mid-June, news of the KOR ONE Hydration Vessel was launched. The response was immediate and overwhelming. News of the KOR ONE was picked up by top sites, including Uncrate, Cool Hunting, Boing Boing, Gizmodo, Yanko, Tree Hugger, Daily Candy, and hundreds more. The results surpassed all expectations—KOR soon found itself oversubscribed for its first year’s capacity.

The KOR ONE story continued to spin into mainstream media including top newspapers (The New York Times), magazines (Oprah’s O Magazine, Outside, Us Weekly, Metropolis, Women’s Running), and TV, with appearances on both CBS’s “The Early Show” and ABC’s “Good Morning America.” It was featured in dozens of gift buyer’s guides for the 2008 holiday season and landed a coveted spot on Oprah’s O List. The KOR ONE clearly connected. Individual bloggers picked up the buzz early and continue to praise it. Unboxing videos and reviews on Amazon show heroic-evangelist users spreading the news of the KOR ONE. The viral power of finely targeted emotional connection becomes clear when you realize that the press release was sent to only a few dozen websites.

Buoyed by the success of the initial release, KOR could afford to bring in an outside PR firm to help with its promotion efforts. Because KOR ONE generated such extreme consumer interest, it has grown its brand without spending anything on advertising. It doesn’t need to. Its heroic evangelists spread the word for them (see Figure 8.2).

© RKS Design

Figure 8.2 Blog posts about KOR ONE

KOR founders and the design team grew their greatest satisfaction from the response of consumers, including ones that they hadn’t envisioned as early consumers. As a young company, the founders had thought about how to align with high fashion and celebrities to raise awareness and visibility. The budget didn’t allow for the glitzy launch, but a grass-roots movement based on shared values was created. Product reviews showed that people latched on to all the pillars of KOR intuitively. As one reader on a blog commented:

“My evil consumer side says, ‘Have to have it.’ My body says, ‘Need to get it.’ My green side says, ‘The earth wants me to have this.’…25–30 bucks? Sold.”

Reward the Consumer

“We save the world by being alive ourselves.”

—Joseph Campbell

“Better Me, Better World.”

—KOR

The final step in the Hero’s Journey involves the return of the Hero to the world he has left, and the sharing of hard-won knowledge with those in his community. In the consumer context, the sharing of a great experience has the same effect: It empowers both the consumer and creates a viral connection. Today, the urgency to the global water crisis has only gotten more intense. More celebrities and ordinary citizens are joining forces. Once regarded as an issue in developing countries, water scarcity and safety are now global concerns. Cirque du Soleil founder Guy Laliberté was one of the first civilian space travelers and dedicated his journey to raise awareness of the global water crisis.

KOR, too, found that the reception the design received created a platform for it to do more to support the cause of global water advocacy. After the successful launch of the KOR ONE, a line of three new colors was created along with a campaign empowering consumers to support different causes related to water with the purchase of their selected color (see Figure 8.3). KOR Water did more than achieve success using design to transform a lucrative but stagnant category. It is an illustration of the “triple bottom line” in practice—a business model that takes into account the interests of consumers, the company, and the planet.

© RKS Design

Figure 8.3 KOR ONE causes: Water Advocacy Campaign

The viral demand that was created resulted in retailers requesting the product. The company hired a dedicated force of sales reps to meet the demand from retailers. Based on feedback from consumers and updating the Psycho-Aesthetics Mapping to reflect the changing marketplace, new items are in development.

The heart of these successes depends on deep understanding of the consumer and tapping into the emotions that can inspire them. It requires a reframing of priorities to making the consumer—not the company—the Hero. It requires rethinking design not as veneer but as a reflection of corporate and consumer values.

The challenges of focusing on emotions require some adjustment. But they are worth making. The fortunes of companies can be fragile. The connections with consumers built through design and experience can provide the insight and the audience to drive change and empowerment for all stakeholders. As the experience of KOR demonstrates, any business success is a matter of persistence, taking risks, and increasingly—design.

Throughout the process, looking at the emotional aspect of alter-natives—whether it was the choice of materials, the launch, and the design itself—led in a different direction than traditional strategic or financial analyses suggested. In the absence of a framework for understanding consumers’ needs and aspirations, it’s difficult to imagine that the same decisions would have been made, especially under pressure. Emotions are even more important when companies are venturing into new areas and new markets, “changing the metaphors” of their industries, and addressing global issues once seen as outside the realm of business.

But learning to unravel the needs and aspirations of consumers (a wicked problem in itself) and learning to apply them systematically can make meeting these challenges more visible, and therefore more possible. Over the years, using Psycho-Aesthetics to empower consumers and stakeholders has helped us both in creating innovation and making agonizing decisions. What you know will get you started. What you need to do will become known. The creative process will still be challenging, but more efficient and transparent. Better solutions and new consumers will emerge as a result. They will share your excitement and help tell the story with you. The result is magic—but the process is predictable.