CHAPTER 8

STRATEGIC ISSUES IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT1

“Every advantage…is judged in the light of the final issue.”

DEMOSTHENES, 384–322 B.C.

8.1 INTRODUCTION

In the management of a project, there are likely to be issues or contentions that can have a significant impact on what purposes the project fulfills—and how the project should be managed. Often project success or failure rides on these issues—and how they have been adequately considered during the planning for and execution of projects. The notion of strategic issues in the management of projects is another area of consideration that broadens the role of the project manager and his or her team members.

In this chapter, the nuclear power industry will be used to provide some representative examples of what is meant by strategic project “issues.” How to identify issues, how to analyze the significance of issues, and how to manage project strategic issues will be suggested. Once the project team has identified the issue and analyzed its real or potential impact on the project, strategies can be developed and executed to deal with those issues that might have an important impact on the management of the project as well as its outcome. Also some insight into why projects succeed and why they fail because of strategic issues will be provided.

8.2 WHAT ARE STRATEGIC ISSUES?

The concept of “strategic issues” has emerged as a way to identify and manage factors and forces that can significantly affect an organization’s future strategies and tactics. The importance of strategic issues has therefore appeared in the literature primarily in the context of the strategic management of an organization. King has put forth the notion of strategic issue management as an integral element of the strategic management of organizations,2 and Brown also has dealt with strategic issues in the management of organizations.3

This chapter describes an approach to the assessment and management of strategic issues facing project teams as well as some strategic issues that have had an impact on contemporary projects.

Project owners need to be aware of the possible and probable impacts of strategic issues. The project team leader has the primary responsibility to focus the owner’s resources in order to deal with project strategic issues. The authors suggest three key aspects of strategic issue management: a need to be aware of strategic issues facing a project, an approach for the assessment of the strategic issues, and a technique for the management of strategic issues.

8.3 SOME EXAMPLES

Sometimes the existence of strategic issues in an industry fosters the use of project management techniques in a fashion not previously used. For example, intense foreign competition in the U.S. automobile industry has prompted U.S. automobile manufacturers to develop innovations in the design of their cars. Cutting costs and cutting car design–development time are other key strategic issues facing U.S. producers. Their response to the need to reduce the time it takes to manufacture a car has, in part, been to use project management techniques in the form of an organizational alignment and a process of engineering manufacturing called simultaneous engineering or use of product design teams. The result: shorter car model product-development cycles with consequent cost savings, improved quality, and a more competitive product in the world car market.

When the Japanese automaker Nissan considered building a plant in the United States, it recognized that a strategic issue facing that project was the adaptability of the local community and the workers to the Nissan culture. By carefully selecting their employees and using exchange trips to Japan, and by orientation sessions at the plant in Tennessee, the Japanese managers were able to resolve this strategic issue, resulting in a successful production facility characterized by model employee-management relations.

Jaafari discusses the strategic issues in the management of macroprojects in Australia by first looking at the typical pattern of managerial relationships that occur and must be administered in such macroprojects. These occur between:

• Each participating owner and the joint venture or company acting as the collective body for owners (herein referred to as the owner)

• The owner and the government(s)

• The owner and the lenders

• The owner and purchasers of the end product(s)

• The owner and insurer/underwriters

• The owner and project manager or engineer-constructor

• The owner and constructors/suppliers and fabricators

• The owner and the designer4

These relationships emerge as the project stakeholders are identified and the nature of their stake is determined. Stakeholders are those persons or organizations that have, or claim to have, an interest or share in the project undertaking. Strategic issues can arise from many different stakeholder groups: customers, suppliers, the public, government, intervenors, and so forth.

In a project, a strategic issue is a condition of pressure, either internal or external, that will have a significant effect on one or more factors of the project, such as its financing, design, engineering, construction, and operation.5 Some examples of the way that contemporary projects have faced strategic issues follow.

On the U.S. Supersonic Transport Program, the managers had too narrow a view of the essential players or stakeholders and generally dismissed the impact of the environment-related strategic issues surrounding the program until it was too late. Environmentalists, working through their political networks, succeeded in stopping the U.S. supersonic program.6

The life cycle of the Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway provides insight into the negative role that strategic issues can play.7 On this waterway project, strategic issues played a role in the consideration of funding for this project over many decades. Political considerations, lawsuits, environmental factors, and social factors delayed approval and construction of the project for extended periods. Although the actual construction of this waterway took almost 14 years, the waterway was 175 years in the making. As far back as 1810, the citizens of Knox County in Tennessee petitioned Congress to provide a waterway to Mobile Bay. Congress finally authorized the first federal study in 1974, but the project was delayed through 22 presidential administrations, 55 terms of Congress, 8 major studies and restudies, and 2 major lawsuits. This waterway is one of the largest civil works projects ever designed and built by the Army Corps of Engineers. About 234 miles long, the project cost $2 billion and required more than 114 major contracts during its construction period.

In contrast to the handling of the Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway, in the Midwest a Water Pollution Abatement Program costing approximately $2.5 million successfully faced challenging strategic issues at the outset and during the early years of the program. The development of a master plan for the project included the development of appropriate environmental impact statements. This master plan could not be changed without court and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) approval. Because the funding for the project included EPA federal grants, state grants, general obligation bonds, and tax district levies, the courts became involved in the planning and execution of the project. The Army Corps of Engineers reviewed all construction contract documents before bidding, reviewed all change orders to the construction contracts, reviewed completed construction, and audited contract administration procedures. All the work that received federal grant participation ultimately was audited by the EPA and Army Corps of Engineers, as well as state and local auditors. In addition, the General Accounting Office conducted periodic reviews of the project. All these stakeholder groups became involved in the legal and regulatory strategic issues that arose on this project. Successful management of this project included the management of not only the project team, but also the project stakeholders and the strategic issues that faced this project throughout its life cycle.

Sometimes a strategic issue arises from the attitudes of employees. For example, CEO George Fisher’s key strategies for turning around Eastman Kodak included a three-phase plan: first, reconfigure Kodak by selling all businesses unrelated to photography, repay most of the debts, and separate the embryonic digital–electronic imaging operations from the traditional chemistry-based silver halide photography division; second, set strict financial goals that included achieving virtual perfection in manufacturing quality; and third, require accelerated growth initiatives. In all of this CEO Fisher was convinced that his most urgent task was to eliminate resistance to change from employees.8

Strategic issues can emerge at any time during a project’s life cycle. The following is an illustration of how costly it can be to ignore them. On a large nuclear power plant project, an offshore earthquake fault was discovered only a few miles from the plant site. This occurred midway through the project’s life cycle. Although the discovery of this fault was obviously a significant strategic issue, there was little evidence that the senior managers of the owner organization demanded and received a “satisfactory accounting” or made any in-depth inquiry to determine its full ramifications. The potential strategic implications of the fault should have prompted the corporate board of directors to do the following:

• Ask for an immediate, in-depth study of its possible and probable effects on the design of the plant.

• Acknowledge the need to forthrightly resolve the effects of the earthquake fault on the seismic design of the plant.

• Order a full-scale audit of the current status of the plant.

The project owner was not able to provide any evidence that the board of directors or the executive committee of the board considered the available options of

• Withdrawing its license application or stopping work

• Significantly reducing work at the site pending a full-scale investigation of the implications of the fault

• Accelerating offshore investigations to speed resolution of any questions that might have been raised

There was no evidence that the board of directors considered any options other than that of continuing work, so that after the plant was nearly completed, the board members were faced with the enormous costly problem of redesigning the plant so that it could function safely in spite of its poor location.9 Public concern over the seismic-geologic potential safety of this plant was expressed through the organized efforts of several intervenor or stakeholder groups acting through the courts to require reassessment, or even cancellation, of the plant.

The successful completion of any substantial public works project is dependent upon the recognition and management of strategic issues surrounding the social, political, legal, and economic aspects of the project as well as the cost, schedule, and technical performance aspects. On these public works, the project can expect to encounter strategic issues such as:

• Land acquisition challenges

• Environmental impacts

• Political support or uncertainty

• Advocacy usually related to who conceives, champions, and nurtures the project and provides ongoing maneuvering to keep the project alive and well—a task partially fulfilled by the project managers

• Intervenors ranging from such organizations as local newspapers to vested interest groups such as the Sierra Club

• Competitors who would like to see the project fail so they could pick up some of or all the action

One of the major strategic issues facing the United States and other nations as well is the development of alternative means for generating electrical power. The energy crisis of 1974 pointed out the imprudence of depending on oil and gas as the principal fuels for generating electric power. Today, that crisis seems to be part of our forgotten past—but it has not gone away. Limited research is being carried out in projects leading to the development of alternative means of producing electrical power. In the judgment of the authors, another energy crisis is forthcoming. It is not a question of whether such a crisis will emerge—it is a question of when. Although many people will disagree with the authors’ opinion in this regard, what if such a crisis does come forth? What alternative means for generating electrical power will be available? One such alternative source is nuclear power. But this source is not acceptable to most people because of the history at the Three Mile Island facility and the experiences at Chernobyl. Then, too, the poor management of the construction of nuclear power plants in the United States causes a lot of concern about whether or not the design and construction of plants in the future would do any better.

Jack Welch, General Electric Company’s CEO for nearly 20 years, forged an entrepreneurial culture that kept the company at the forefront of U.S. industries. He once observed, “Managing success is a tough job. There’s a very fine line between self-confidence and arrogance. Success often breeds both, along with a reluctance to change.” When Welch attempted to merge Honeywell with GE, this attitude seemed to be more than self-confidence and the merger met with failure.

Welch did not adequately assess the influence of the European Commission, and specifically the Commission’s top antitrust official. Welch was confident of the outcome of the GE-Honeywell merger because of his successes in 1700 other mergers during his 20-year tenure. What was not considered was

• A growing sense of rivalry between the European and the U.S. aerospace companies

• Cultural sensitivities

• Tough top antitrust officials in Europe with a reputation for challenging large mergers

• A perceived arrogance on the part of GE by the Europeans

• European fears that GE would dominate the aircraft maintenance, repair, and overhaul operations in Europe

Observers of the situation attribute Welch’s attitude and lack of understanding of the European culture, including the tough stand taken on large mergers in Europe. This attempted merger, initiated just prior to Welch’s planned retirement, places a stain on his otherwise brilliant career and demonstrates that 1700 successes in the past do not assure success when fundamental areas are ignored.10

8.4 AN APPLICATION OF THE CONCEPT OF STRATEGIC ISSUES: NUCLEAR CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY

Strategic issues vary depending on the industry and the circumstances of a particular project. In the material that follows, the nuclear plant construction industry is used to illustrate the concept of strategic issues as applied to a select industry. This industry has been chosen because of the many strategic issues that have faced the industry—issues which relate to a particular project as well as to the many generic issues that confront project owners, managers, constructors, designers, regulators, investors, local communities, consumers, and other vested stakeholder groups.

A project that has as long a life cycle as a nuclear power generating plant will be affected by many issues (some of them linked) that are truly strategic in nature. For example, the typical strategic issues that a nuclear power plant project faces today include:

• Licensability

• Passive safety

• Power costs

• Reliability of generating system

• Nuclear fuel reprocessing

• Waste management

• Capital investment

• Advocacy

• Environment

• Safeguards11

The U.S. nuclear power industry has had extraordinary challenges in the past such as uncertain licensing procedures, project cost and schedule control problems, quality assurance disputes, intervenor actions, and other conditions that are strategic issues to be dealt with by a project team in managing a nuclear power plant project. A discussion of these issues follows.

Licensability

All U.S. nuclear plants, to be licensed, must meet federal codes and standards as well as the nuclear regulatory guides for the particular design. But many of these codes, standards, and guides are not applicable to a new concept and design that have not been licensed previously. The first of a kind becomes precedent-setting and will receive a commensurate amount of attention from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) staff—so much so that joint groups will be set up with representation from the Department of Energy (DOE), NRC, and a bevy of consultant experts to answer the hundreds of questions posed by the NRC staff and to draft appropriate revisions to the existing federal codes and regulations as well as to set up future guides for the new concept.

Passive Safety

All the commercial reactors built and operated in the United States today require the activation, within a prescribed period, of an auxiliary shutdown system, either automatic or manual. At present, if one allows the reactor to operate without adding reactivity (a process similar to adding coal to a fire) and assuming that the cooling systems remain effective (the pumps operate, the valves open and close on cue, the heat exchangers transfer heat, etc.), the reactor should eventually bring the auxiliary system into operation. The difficulty comes when the auxiliary system cannot halt or lower the reactivity (like removing coal from the fire) and/or maintain the effectiveness of the cooling systems.

Power Costs

The components of power costs are capital costs, operations and maintenance (O&M), and fuel costs. For a typical nuclear power plant, the capital cost component is four times the O&M cost, which is approximately equal to the fuel cost. Hence, it is evident that capital cost is the most significant component.

Construction times for many recent U.S. nuclear plants have exceeded 10 years. The U.S. licensing and judicial procedures have accounted for much of the delay, but other factors, such as imprudent project management, also have taken their toll. Whatever the reasons, the delays have an extraordinary impact on the resultant capital investment in these plants even before they have produced 1 kWh of electricity.

Reliability of Generating System

The reliability of a nuclear power plant must be extremely high, particularly in the safety systems and components. There are reliability differences from one model to another; that is, one might have fewer moving parts, fewer systems, fewer components, and fewer things to go wrong.

Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing

Commercial nuclear fuel reprocessing in the United States is limited. Instead, the U.S. government has agreed, for a price, to accept the spent fuel from U.S. reactors for long-term storage. Europe and Japan, however, have viable programs to recover for future use the nuclear fissionable fuel from spent fuel assemblies.

Waste Management

Public reaction to shipments of nuclear waste is becoming increasingly severe. Therefore, minimum waste streams and minimum movement of such wastes outside the plant boundaries are advisable. The waste disposal program conceived and managed by the U.S. government and the nuclear power industry to store radioactive fuel safely is being challenged under public pressure.

Capital Investment

Closely akin to the strategic issue of power costs are the financial exposure and risks that investors of nuclear power plants have experienced over the last several years.

Public Perception

Aggravated by the nuclear accidents at Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, the increasingly negative public perception of nuclear power and its associated risks has made this strategic issue more acute, and the need for government research programs more pressing.

Advocacy

Not many government interest research programs can proceed through the government bureaucracy without a strong advocate who can gain substantial support for the program. A reactor manufacturer who contemplates obtaining government funds to research advanced nuclear reactors should determine what advocacy exists for such research, both in the government and in the corporation.

Environment

From an environmental viewpoint, the nuclear advocates had essentially convinced the general public that nuclear power plants were environmentally benign—until the media convinced the public otherwise after the Three Mile Island incident. The Chernobyl incident reinforced the sense that nuclear power was a serious threat to the environment and to life itself.

Safeguards

The objective of nuclear safeguards is to keep fissionable material out of unauthorized hands. A nuclear plant security system that does this better than another should have a competitive edge.

8.5 MANAGING PROJECT STRATEGIC ISSUES

Project strategic issues often are nebulous, defying management in the literal sense of the word. It is important that the project team identifies the strategic issues the project faces and deals with them in terms of how they may affect the outcome of the project. In the assessment of the issues, some may be set aside as not having a significant impact on the project. These would not be reacted to but would be monitored to see if any changes occur that could affect the project. Of course, some significant issues may not be subject to the influence of the project team.

A useful technique to identify strategic issues facing a project is to keep a running tally of all issues that face the project and then take time to have the project team discuss these issues to see which ones are operational (short term) and which are strategic (in the manner described in this book). Once the project team has been acquainted with the notion of strategic issues, each member should be encouraged to note any emerging issues for discussion and review at one of the regular project team meetings. During this meeting all issues should be reviewed, selecting those that appear to be relevant and assigning a member of the team to follow the issue and keep the project team aware of it and its implications on the project’s future. More serious issues may require the appointment of an investigative subproject team that will report back to the full team. An example of how one project team’s awareness on strategic issues early in the project’s life cycle proved useful appears later.

A kickoff meeting of the project team and the senior managers from the owner’s organization was held to get the project team organized and to start preliminary project planning. During this 3-day meeting a tally was made of issues known to impact or have potential future impact on the project. Some issues were determined to be truly strategic, and the group decided to track them to determine their significance. If such a tally had not been done and if the preliminary discussions had not been carried out, it is highly probable that some of the more important issues might not have surfaced until the project was into its life cycle. By then an orderly and timely resolution of some of these issues would have been difficult, if not impossible. This suggests that an important part of any project review meeting is to discuss and update the current project issues to see which ones might be added. By the same process, those issues judged as no longer important could be put aside.

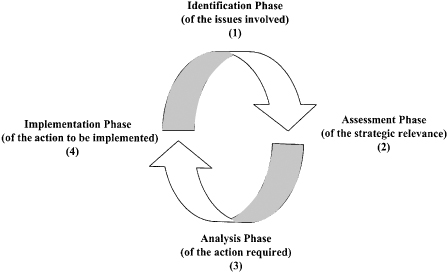

The project team requires a philosophy on how to manage strategic issues. A phased approach is suggested as portrayed in Fig. 8.1. These phases are discussed below.

FIGURE 8.1 An approach for the management of strategic issues.

8.6 ISSUE IDENTIFICATION

Identifying some of the issues often can come about during the selection of the project to support the organizational strategy. During the selection process, the following criteria can be addressed to determine if the project truly supports organizational strategy:

• Does the project support a strength that the enterprise holds?

• Does it avoid a dependence on something that is a weakness of the enterprise?

• Does the project support an organizational need?

• Is there a customer who is willing to pay for the project?

• Can the project owner assume the risk that is involved in the project?

• Are the resources and management skills available to bring the project to completion on time and within budget?12

As the decision makers seek the answers to these questions, there will be some strategic issues that emerge naturally. Other issues can be identified by the project team during its planning, evaluation, and control meetings.

For example, during a customer review of a bid package for a new weapon system, an aerospace contractor’s project proposal team discovered that the customer had serious doubts about the contractor’s cost-estimating ability. This concern prompted the contractor to engage a consultant to conduct a survey of its customers to assess its image in two general areas: product image (price, quality, reliability, etc.) and organizational image (quality of personnel, responsiveness, integrity, etc.). Both structured and unstructured personnel interviews were conducted with key customer personnel. One significant outcome of this image survey was the perception by key customer personnel that the contractor’s cost estimates were far too conservative, invariably resulting in excessive cost overruns. The contractor’s key executives were shocked by the customer’s perceptions of its cost performance credibility. This matter of credibility immediately became an urgent strategic issue within the contractor’s organization. A task force was formed to investigate the issue and recommend a strategy on how to deal with it. In their deliberations, the task force found that the contractor’s cost performance was in fact quite credible, and that the perception held by the customer’s key people was not valid. Consequently, the contractor mounted an advertising and indoctrination program to change the customer’s viewpoint by working through the field marketing people and by visiting the customer’s offices to present the actual facts on contractor cost performance. The result was a resolution of the strategic issue in the contractor’s favor. Had the project proposal team not been alerted to this potential strategic issue, the contractor may well have lost future government contracts.

By maintaining close contact with the customer, an opportunity is provided to identify issues that can have an impact on the project. Another technique is to examine the stakeholders on the project to see if the nature of their claims suggests any strategic issues.13 As each stakeholder group is reviewed, the following questions should be addressed:

• What claims do the stakeholders have in the project?

• How might the claims affect the outcome of the project?

• What resources and influence do the stakeholders have to push the satisfaction of their claims?

• Can the project live with the stakeholder’s purposes and motivation?

• Can the outcome of the stakeholder’s claim on the project be predicted?

• What can the project team do about these claims?

Other techniques can be used such as the nominal group technique14 or brainstorming to aid in the identification of issues. Perhaps the best way to identify issues is to ensure that the project team is well organized, well managed, and well aware of the larger systems context (economic, political, social, technological, and competitive) of the project. If the team meets these conditions, there is a better likelihood that most of the important and relevant strategic issues will surface.

8.7 ASSESSMENT OF AN ISSUE

The act of assessing an issue entails judging its importance in terms of its impact on the project. King has suggested four criteria for first assessing an issue as strategic and then moving to subsequent states of management of the issue:15

• Strategic relevance

• Actionability

• Criticality

• Urgency

The strategic relevance of an issue relates to whether it will have a long-term impact (more than 1 year) on the project. Most of the strategic issues mentioned earlier in this chapter could be considered to be strategically relevant, such as licensability, passive safety, and power costs. Strategic relevance addresses the question: Will this strategic issue influence the project strategy or the likely consequences of the strategies that are being followed on the project? If an issue is strategy-relevant, then the project manager has two basic courses of action: Try to live with the issue’s impact, or do something about the issue.

But some strategic issues will be beyond the authority and resources of the project manager to resolve. In such situations, a third course is open to the project manager: Elevate the issue to senior managers for their analysis and possible evaluation. Even though senior managers are aware of the issue, the project manager retains residual responsibility to see that the issue is “tracked” and given due attention.

The actionability of a project issue deals with the capability of the project team and the enterprise to do something about the issue. For example, the issue of licensability of a new nuclear power plant is critical to the decision of whether to fund such a plant. A company can help resolve the licensability of nuclear power plants by participating with the industry’s groups that are trying to influence the Nuclear Regulatory Commission either directly or through congressional persuasion to do something about the uncertainties related to licensing. Such participation would be useful in influencing the strategic issue as well as for keeping informed about the status of the issue. The related strategic issue of funding support for a power-generating plant would be an issue that the enterprise would actively try to resolve by working with investment bankers in the financial community.

A project may face strategic issues about which little can be done. Keeping track of the issue and considering its potential impact on project decisions may be the only realistic action the team can take. Key project managers should always be aware that there are issues that may be beyond their influence.

The criticality of an issue is the determined impact that the issue can have on the project’s outcome. The issue of growing congressional disenchantment with the U.S. Supersonic Transport Program arose from the concern of the environmentalists over the sonic boom problem. Proactive environmental groups along with the general public exerted political influence, which contributed to the termination of that program. Project advocates recognized too late that the sonic boom controversy was the critical fulcrum for the environmentalists to use for their public and congressional support. If a preliminary analysis of an issue indicates it is noncritical, then the issue should be monitored and periodically evaluated to see if its status has changed.

The urgency of an issue has to do with the time period in which something needs to be done. All else being equal, if an issue should be dealt with immediately, it must take precedence over other issues. Urgent issues emerging during the project planning should be considered a “work package” in the management of the project. Someone should be designated as the issue work package manager to look after the issue, particularly during its urgency status.

8.8 ANALYSIS OF ACTION

Identification and assessment of an issue are not enough; the issue has to be managed so that its adverse effect on the project is minimized and its potential benefit is maximized. The issue work package manager is in charge of collecting information, tracking the project, and ensuring that the issue remains visible to the project team. That manager should also coordinate decisions made and implemented regarding the issue.

In the analysis of action required to deal with an issue, seeking answers to a series of questions like the following can be helpful:

• What will be the probable effect of the issue in terms of impact on the project’s schedule, cost, and technical performance and the owner’s strategy?

• Who are the principal stakeholders who have an interest in the project? What will be the impact on their probable strategy?

• How influential are these stakeholders?

• What strategy should the project team develop to deal with these issues?

• What might be the real cost in relation to the apparent cost to the project owner, and will other projects being funded by the project owner be affected?

• What specific action will be required, and what will it cost the project owner?

The action developed to deal with the issue may, at the minimum, consist of simply monitoring the issue and giving status reports to the project team. Some issues, however, may require a more aggressive approach. The issue work package manager may find it useful to think of the issue as having a life cycle, with such phases as conception, definition, production, operations, and termination, and to identify the key actions to be considered and accomplished during each phase. The manager should be specific and should stipulate what will be done, when it will be done, how to do it, where, and who will be in charge of implementing the action leading to resolution of the issue.

8.9 IMPLEMENTATION

However it is dealt with, the resolution of an issue or the mitigation of its effects requires that a project plan of action be developed and implemented. Indeed, the resolution of a strategic issue can be dealt with as a miniproject requiring the execution of the management functions—planning, organizing, motivating, direction, and control—and all these functions entail some degree of work breakdown analysis, scheduling, cost estimating, matrix responsibility, information systems, design of monitoring and control, and so on. What resources are to be used to resolve the issue and who should take the leadership role in resolving that issue and the crucial questions to be answered should be considered.

The potential for the success or failure of a project can have strategic issue implications. In the material that follows, a brief review of some of the reasons for project success and failure is given to remind the leader that such issues are very real and should be considered during the project’s life cycle.

8.10 STRATEGIC ISSUES OF PROJECT SUCCESS AND FAILURE

In 1945, Mayo observed that the United States is technically competent, but we have considerable social incompetence.16 Another perspective is offered by two researchers who found that for the overwhelming majority of failed projects there was not a single technological issue to explain the failure—rather, it was sociological in nature.17 Thamhain and Wilemon found in their research that newer project management approaches require more extensive human skills and competence. Some of the skills they found that were associated with building multidisciplinary teams involved motivating staff people, developing a healthy work climate, managing conflict, and communicating effectively at all levels.18

What are the key critical factors in successful projects? One study identified a general set of critical success factors that could be applied to any project regardless of its characteristics or development methodology. It was recognized that timing was evident in the factors. The top factors identified were those concerned with establishing adequate planning to include goals and the general philosophy and mission of the project, as well as the commitment to these goals. Factors associated with user involvement tended to take up the middle of the rankings. Finally, at the low end of the factors were the project management and technical factors to include the selling of the system, the monitoring of progress, and troubleshooting activities usually found during project development activities.19

Another study about project success formulates a conceptual framework to assess the impact of success factors on the success criteria of a technology transfer project. The study drew from a sample of 40 automation industry firms and 48 successful and not so successful cases. The dominant importance of involvement for the success of a technology transfer project became evident. Technical characteristics are the second most important factor in determining project success. One key outcome of this study was a list of policy implications and recommendations to enhance the technology transfer process.20

Florida Power and Light management identified what it thought to be the 10 most important factors in completing the St. Lucie 2 Nuclear Power Plant essentially on schedule, within cost, and without major quality-related problems:

• Management commitment

• A realistic and firm schedule

• Clear decision-making authority

• Flexible project control tools

• Teamwork

• Maintaining engineering ahead of construction

• Early start-up involvement

• Organizational flexibility

• Ongoing critique of the project

• Close coordination with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission21

The potential for a project failure or success usually has strong overtones of a strategic issue. If a product development project fails, the strategic viability of the enterprise can be threatened. Conversely, if a project succeeds, a significant contribution to the future viability of the enterprise has been made. Project managers, team members, and senior managers should be aware of how strategic issues can impact the success or cause failure of a project.

8.11 TO SUMMARIZE

The major points expressed in this chapter include:

• In a project, a strategic issue is a condition of pressure, either internal or external, that will have a significant effect on one or more factors of the project, such as its financing, design, engineering, construction, and operation.

• Examples were given of how strategic issues impacted some of the projects in the past and in contemporary times.

• The principal strategic issues facing potential projects for the construction of nuclear power plants were presented to keynote the importance of effectively managing the strategic issues in a project.

• Strategic issues on a project can arise from within the enterprise, and from outside, such as major concerns that the project stakeholders have about the project.

• Potential strategic issues likely to impact a project during its life cycle should be identified during the early planning stages for the project.

8.12 ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

The following additional sources of project management information may be used to complement this chapter’s topic material. This material complements and expands on various concepts, practices, and theory of project management as it relates to areas covered here.

• John D. Sterman, Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World (Burr Ridge, Ill.: McGraw-Hill, 2000). It is not enough to identify the strategic issues in projects, but one must be able to solve those issues through analysis and application of working models. This book provides the basis for strategic thinking in the context of business, engineering, and social and physical sciences.

• Stephen G. Haines, The Systems Thinking Approach to Strategic Planning (Boca Raton, Fla., Saint Lucie Press, 2000). This book is a practical application to systems thinking and improves on the systems thinking concept first introduced by Peter Senge in the Fifth Discipline (Doubleday, 1990). This book focuses on planning strategies and the change management process in support of customer satisfaction.

• Anonymous, “Seattle Light Rail in Question,” Railway Age, June 2001. This article describes the cost overrun and schedule delay of the Seattle Light Rail Transport System. It introduces the issue of cost and schedule growth by approximately one-third and the challenges associated with this project.

• Anonymous, “Thinking Outside the Box,” Chain Store Age, May 2001. This article addresses numerous issues that face organizations when considering doing business in a particular state, county, or municipality. If a project was being planned for a particular location, the list of challenges to good business would be invaluable. With projects bridging several communities, such as a telecommunication tower project, the issues described would apply and require resolution for the best outcome.

• William R. Bigler, “The New Science of Strategy Execution: How Incumbents Become Fast, Sleek Wealth Creators,” Strategy & Leadership, May–June 2001, pp. 29–34. This article focuses on the delays in implementing strategies for firms and the resultant chaos. Discussion centers on the identification of opportunities and rapid implementation to achieve the desired outcome.

8.13 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Define a strategic issue.

2. Select a project management situation from your work or school experience, and list the strategic issues.

3. What methods might project managers employ to identify the strategic issues of a project?

4. What approaches can be used by project leaders to assess the impact of a strategic issue?

5. What management techniques can be used to address strategic issues?

6. What roles do environmental issues play in projects such as power plants and other major construction projects?

7. List and define the elements of the phase approach to dealing with strategic issues.

8. In identifying the strategic issues of a project, management can ask questions pertaining to the project stakeholders. What kinds of questions should be asked?

9. What is meant by the strategic relevance of an issue?

10. How can management assess the criticality and urgency of a strategic issue?

11. How can managers ensure that project team members are aware of and understand the project strategic issues?

12. What trends can be recognized when project portfolio management categorizes projects?

13. Discuss the use of project portfolio management when an organization has not fully developed and announced its strategic goals and objectives.

14. What advantages do you see for using project portfolio management in your organization?

15. How does project portfolio management affect the allocation of resources in your organization?

8.14 USER CHECKLIST

1. Do the project managers of your organization understand the concept of strategic issues? How do they manifest this understanding in managing projects?

2. Do any formal methods exist in your organization for strategic issue management? What are they? How are they used?

3. Do the project managers of your organization attempt to identify project interfaces that can seriously impact the outcome of a project? Explain.

4. Does top management use any postproject appraisals to help uncover strategic issue-related problems? Does management see the value in postproject appraisals?

5. Does the management of your organization recognize the importance of understanding public perception? In what ways do project managers control public perception?

6. Are there any outside advocates that can be or are effective in altering public opinion in favor of your organization’s projects?

7. Do project managers assess the environmental impacts of projects? In what ways?

8. Could the phase approach to managing strategic issues be used effectively in your organization? How?

9. Are current project managers kept informed of the factors likely to impact project success or failure?

10. Does management seek to identify the relevant issues for each project stakeholder?

11. Does management identify the strategic relevance of each issue and determine the actionability, criticality, and urgency? In what ways is this done? What other methods could be used?

12. Are project team members made aware of strategic issues? How? Do they then attempt to monitor these issues as they relate to their own work packages?

8.15 PRINCIPLES OF PROJECT MANAGEMENT

1. Strategic issues may adversely impact project success through inadequate attention being paid to the issues.

2. Large, long-term projects have a great potential for cost overruns and schedule delays.

3. Relationships between the project owner and others are critical to the success of the project.

4. Large projects have diverse stakeholders who may not agree on the risk of the project or the benefits of its product.

5. Anticipating and addressing strategic issues materially improves the chance for successful projects.

8.16 PROJECT MANAGEMENT SITUATION—SOME STRATEGIC ISSUES

When an organization changes from its present type of work to a new competency, there are typically uncharted courses taken. The obvious impediments to change are easy to identify and resolve through some routine planning or contingency action. It is the unanticipated issues that will create problems—emerging when other activities are taking the time and resources or slowly materializing in a fashion so that it is difficult to characterize the issue.

Anticipating issues for a major change of direction for an organization may be unsuccessful for several reasons. There may not be someone knowledgeable available to review the plans and identify potential problems. Also, the organization’s plan for change may have weak goals that are unclear or not understood. This anticipated change is probably a new venture for the organization that is based more on a desire to reposition than the facts regarding difficulty for the change.

One of the more challenging situations is to assume that because the competition has made a similar change, this organization can also transition to the new position with relative ease. It must be remembered that the competition will neither share the difficulty of the transition nor share information on the success of their transition. It is not in a competitor’s interest to help another position to compete for a part of the market.

Strategic issues may be a part of the operating environment, such as performing work in a foreign country using indigenous unskilled labor or conforming with laws or customs of the foreign country, that must be considered during the decision-making process. The best method of meeting strategic issues and resolving them through various means is to be well armed with information.

Issues that affect relationships in a foreign country may be derived from religious followings, language barriers and language translations, work ethics, local and federal laws, customs of the population, labor unions, trade barriers, and human skill levels. It takes an expert on the country to identify these differences from what is current practice in the United States. Some issues may arise from what one would assume is a favorable situation for the local population.

For example, apparently favorable situations such as employment and good wages can cause competition among those seeking jobs and possible sabotage of the work by those not employed. Some countries require that groups of people be hired for jobs, rather than the typical model of hiring one person at a time. These same groups may require that the leader be paid, but that he will not be required to work or supervise. If work instructions are given in English, the worker may often use lack of communication as the excuse for poor performance.

Initiating a venture that can develop strategic issues can be difficult to complete without thorough planning with a lot of information and a process to handle emerging issues. Failed projects may be the outcome when the organization is overcome by issues that seem to have no immediate answer.

8.17 STUDENT/READER ASSIGNMENT

1. You are the project manager for a light manufacturing firm and it has been decided that the work can be done at less overall cost if the items are manufactured in Dalian, China. What issues do you anticipate with manufacturing the products in China?

2. A competitor has a major coffee-growing effort in Ethiopia and seems to be doing well. Management has decided to invest in a project in Ethiopia to start a major wool-growing effort that will provide cheap wool for the world market. What issues do you see in this venture?

3. Your organization, an experienced mine operator in the United States, has been invited to participate in a major mining operation in northern Canada. You have been tasked with identifying any issues associated with partnering on the new mine. What are the issues?

4. Your organization has been awarded a contract to build an airfield in the Sudan. All construction equipment will be transported to the location. One of the issues is that heavy equipment operators are not available from the indigenous labor force. What are some of the means to resolve this issue?

5. While working in a foreign country, you identify the issue that the computers are not working properly because of the difference in frequency of the local electricity (50-Hz current versus 60-Hz current in the United States). Your project management scheduling tools as well as clocks are not working properly. What action should you take to resolve this issue?