Yes, yes, let’s talk about the weather. | ||

| --W. S. Gilbert, The Pirates of Penzance, or the Slave of Duty | ||

Even if you’re not called upon to re-create extreme climate conditions (as someone once pointed out seems to be a theme in my work), even a casual glance out the window demonstrates that the meteorological phenomena are always in play: a breeze is blowing in the trees, or water and particulate in the air are changing the appearance of buildings and the land closest to the horizon.

This chapter offers methods to create natural elements such as particulate and wind effects, as well as to replace a sky, or add mist, fog, or smoke, or other various forms of precipitation. All of these are more easily captured with a camera than re-created in After Effects, but sometimes the required conditions aren’t available on the day of a shoot. Mother nature is, after all, notoriously fickle, and shooting just to get a particular environment can be extraordinarily expensive.

It’s rare indeed that weather conditions cooperate on location, and even rarer that a shoot can wait for perfect weather or can be set against the perfect backdrop. Transforming the appearance of a scene using natural elements is among the more satisfying things you can do as a compositor.

Particulate matter in the air influences how objects appear at different depths. What is this matter? Fundamentally, it is water and other gas, dust, or visible particulate usually known as pollution. Even in an ideal, pristine, pollution-free environment there is moisture in the air—even in the driest desert, where there also might be heavier forms of particulate like dust and sand. The amount of haze in the air offers clues as to

The distance to the horizon and of objects in relation to it

The basic type of climate; the aridness or heaviness of the weather

The time of year and the day’s conditions

The air’s stagnancy (think Blade Runner)

The sun’s location (when it’s not visible in shot)

Notes

Particulate matter does not occur in outer space, save perhaps when the occasional cloud of interstellar dust drifts through the shot. Look at photos of the moon landscape, and you’ll see that the blacks in the distance look just as dark as those in the foreground.

The color of the particulate matter offers clues to how much pollution is present and what it is, even how it feels: dust, smog, dark smoke from a fire, and so on (Figure 13.1).

Essentially, particulate matter in the air lowers the apparent contrast of visible objects; secondarily, objects take on the color of the atmosphere around them and become slightly diffuse. This is a subtle yet omnipresent depth cue: With any particulate matter in the air, objects lose contrast further from camera; the apparent color can change quite a bit, and detail is softened. As a compositor, you use this to your advantage, not only to re-create reality, but to provide dramatic information.

Figure 13.2 shows how the same object at the same size indicates its depth by its color. The background has great foreground and background reference for black and white levels; although the rear plane looks icy blue against gray, it matches the look of gray objects in the distance of the image.

Figure 13.2. One plane (white circle) is composited as if it is a toy model in the foreground, the other (black circle) as if it is crossing the sky further in the distance; a look at just the planes shows them to be identical but for their color (left). The difference between a toy model airplane flying close, a real airplane flying nearby, and the same plane in the distant sky is conveyed with the use of Scale, but just as importantly, with Levels that show the influence of atmospheric haze.

The technique used here is the same as the one outlined in Chapter 5 with the additional twist that now you understand how atmospheric haze influences the color of the scene. Knowing how this works from studying a scene like this one helps you create something similar from scratch even without such good reference.

The plane as a foreground element seems to make life easier by containing a full range of monochrome colors. When matching a more colorful or monochrome element, you can always create a small solid and add the default Ramp effect. With such a reference element, it is simple to add the proper depth cueing with Levels and then apply the setting to the final element (Figure 13.3).

Figure 13.3. If your foreground layer lacks the full range of values, match a grayscale gradient, then swap in the element. These gradient squares have the same settings as the planes in 13.2.

To re-create depth cues in a shot from scratch, you must somehow separate the shot into planes of distance. If the source imagery is computer-generated, the 3D program that created it can also generate a depth map for you to use. If not, you can slice the image into planes of distance, or you can make your own depth map to weight the distance of the objects in frame (Figure 13.4).

There are several ways in which a depth map can be used, but the simplest approach is probably to apply it to an adjustment layer as a Luma (or Luma Inverted) Matte, and then add Levels or other color correction adjustment to the adjustment layer. Depth cueing would be applied to the furthest elements, so applying this matte as a Luma Inverted Matte and then flashing the blacks (raising the Output Black level in Levels) adds the effect of atmosphere on the scene.

Tip

Getting reference is easy for anyone with an Internet connection these days, thanks to sites and services like flickr.com and Google image search.

Depth data may also be rendered and stored in an RPF file, as in Figure 13.5 (which is taken from an example included on the disc as part of 13_multipass.aep). RPF files are in some ways crude, lacking even thresholding in the edges (let alone higher bit depths), but they can contain several types of 3D data, as are listed in the 3D Channel menu. This data can be used directly by a few effects to simulate 3D, including Particle Playground, which accepts RPF data as an influence map.

Notes

One good reason to use a basic 3D render of a scene as the basis for a matte painting is that the perspective and lens angle can be used not only for reference, but to generate a depth map, even if the entire scene is painted over.

More extreme conditions may demand actual 3D particles, which are saved for later in the chapter.

Sky replacement is among the most inexpensive and fundamental extensions that can be made to a shot. It opens up various possibilities to shoot faster and more cheaply. Not only do you not have to wait for ideal climate conditions, you can swap in a different sky or an extended physical skyline.

Skies are, after all, part of the story—often a subliminal one, but occasionally a starring element. An interior with a window could be anywhere, but show a recognizable skyline outside the window and locals will automatically gauge the exact neighborhood and city block of that location, along with the time of day, time of year, weather, outside temperature, and so on, possibly without ever really paying conscious attention to it.

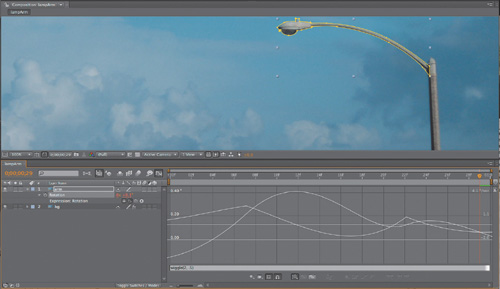

You could spend tens (even hundreds) of thousands of dollars for that view apartment on Central Park East to film a scene at golden hour (the beautiful “hour” of sunset that typically lasts about 20 minutes and is missing on an overcast day). The guerilla method would be to use your friend’s apartment, light it orange, shoot all day, and add the sunset view in post. In many cases, the real story is elsewhere, and the sky is a subliminal (even if beautiful) backdrop that must serve that story (Figures 13.6).

Figure 13.6. For an independent film with no budget set in San Francisco, the director had the clever idea of shooting it in a building lobby across the bay in lower-rent Oakland (top left), pulling a matte from the blue sky (top center), and match moving a still shot of the San Francisco skyline (from street level, top right) for a result that anyone familiar with that infamous pyramid-shaped building would assume was taken in downtown San Francisco (bottom). (Images courtesy of The Orphanage.)

Study the actual sky (there may be one nearby as you read this) or even better, study reference images, and you may notice that the blue color desaturates near the horizon, cloudless skies are not always so easy to come by, and even clear blue skies are not as saturated as they might sometimes seem.

Some combination of a color keyer, such as Keylight, and a hi-con luminance matte pass or a garbage matte, as needed, can remove the existing sky in your shot, leaving nice edges around the foreground. Chapter 6 focuses on strategies for employing these, and Chapter 7 describes supporting strategies when keys and garbage mattes fail.

The first step of sky replacement is to remove the existing “sky” (which may include other items at infinite distance, such as buildings and clouds) by developing a matte for it. As you do this, place the replacement sky in the background; a sky matte typically does not have to be as exacting as a blue-screen key if the replacement sky is also fundamentally blue, or if the whole image is radically color corrected as in Figure 13.7.

A locked-off shot can be completed with the creation of the matte and a color match to the new sky. If, however, there is camera movement in the shot, you might assume that a 3D track is needed to properly add a new sky element.

Typically, that’s overkill. Instead, consider

When matching motion from the original shot, if anything in the source sky can be tracked, by all means track the source.

If only your foreground can be tracked, follow the suggestions in Chapter 8 for applying a track to a 3D camera: Move the replacement sky to the distant background (via a Z Position value well into four or five digits, depending on camera settings). Scale up to compensate for the distance; this is all done by eye.

A push or zoom shot (Chapter 9 describes the difference), may be more easily re-created using a tracked 3D camera (but look at Chapter 8 for tips on getting away with a 2D track).

The basic phenomenon to re-create is the scenery at infinite distance that moves less than objects in the foreground. This is the parallax effect, which is less pronounced with a long, telephoto lens, and much more obvious with a wide angle. For the match in Figure 13.6, a still shot (no perspective) was skewed to match the correct angle and tracked in 2D; the lens angle was long enough and the shot brief enough that they got away with it. A simpler example is included on the disc.

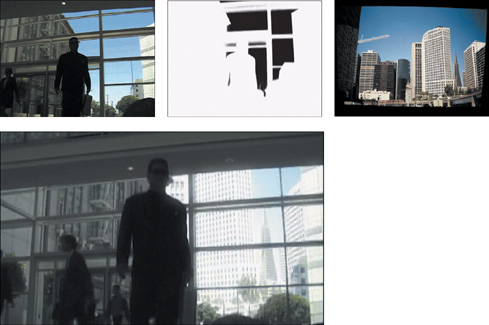

An animated layer of translucent clouds is easy to re-create in After Effects. The basic element can be fabricated by applying the Turbulent Noise effect to a solid, then adding a blending mode such as Add or Screen with the appropriate Opacity setting. On the book’s disc, 13_smokyFlyover. aep contains a simple example of layers of smoke laid out as if on a three-dimensional plane.

Turbulent Noise at its default settings already looks smoky (Figure 13.8); switching the Noise Type setting from the default, Soft Linear, to Spline improves it. The main thing to add is motion, which I like to do with a simple expression applied to the Evolution property: time*60 (I find 60 an appropriate rate in many situations, your taste may vary). The Transform properties within Fractal Noise can be animated, causing the overall layer to move as if being blown by wind.

Figure 13.8. The new Turbulent Noise effect (shown at the default setting) is a decent stand-in for organic-looking ambient smoke and fog. Animate the Evolution if you want any billowing of the element. The same alternate Fractal Types as found in the older Fractal Noise effect are available, as seen in the pop-up menu.

Brightness, Contrast, and Scale settings influence the apparent scale and density of the noise layer. Complexity and Sub settings also affect apparent scale and density, but with all kinds of undesirable side effects that make the smoke look artificial. The look is greatly improved by layering at least two separate passes via a blending mode (as in the example project).

When covering the entire foreground evenly with smoke or mist, a more realistic look is achieved using two or three separate overlapping layers with offset positions (Figure 13.9). The unexpected byproduct of layering 2D particle layers in this manner is that they take on the illusion of depth and volume.

The eye perceives changes in parallax between the foreground and background and automatically assumes these to be a byproduct of full three-dimensionality, yet you save the time and trouble of a 3D volumetric particle render. Of course, you’re limited to instances in which particles don’t interact substantially with movement from objects in the scene; otherwise, you instantly graduate to some very tricky 3D effects (although I have seen it done in After Effects with warps).

Notes

Fractal Noise texture maps maintain the advantage over Turbulent Noise in that they can loop seamlessly (allowing reuse on shots of varying length). In Evolution Options, enable Cycle Evolution, and animate Evolution in whole revolutions (say, from 0° 2 × 0.0°). Set the Cycle (in Revolutions) parameter to the number of total revolutions (2). The first and last keyframes now match, and a loopOut("cycle") expression continues this loop infinitely.

Particle layers can be combined with the background via blending modes, or they can be applied as a Luma Matte to a colored solid (allowing you to specify the color of the particles without having a blending mode change it).

To add smoke to a generalized area of the frame, a big elliptical mask with a high feather setting (in the triple digits even for video resolution) will do the trick; if the borders of the smoke area are apparent, increase the mask feather even further (Figure 13.10).

Figure 13.10. This mask of a single smoke element from the shot in Figure 13.8 has a feather value in the hundreds. The softness of the mask helps to sell the element as smoke and works well overlaid with other, similarly feathered masked elements.

The same effect you get when you layer several instances of Turbulent or Fractal Noise can aid the illusion of moving forward through a misty cloud. That’s done simply enough (for an example of flying through a synthetic cloud, see 13_smokyLayers.aep), but how often does your shot consist of just moving through a misty cloud? Most of the time, clouds of smoke or mist are added to an existing shot.

You can use the technique for emulating 3D tracking (see Chapter 8) to make the smoke hold its place in a particular area of the scene as the camera moves through (or above) it. To make this work, keep a few points in mind:

Each instance of Fractal Noise should have a soft elliptical mask around it.

The mask should be large enough to overlap with another masked instance, but small enough that it does not slide its position as the angle of the camera changes.

A small amount of Evolution animation goes a long way, and too much will blow the gag. Let the movement of the camera create the interest of motion.

Depending on the length and distance covered in the shot, be willing to create at least a half-dozen individual masked layers of Fractal Noise.

Close-Up: Selling the Effect with Diffraction

There is more to adding a cloud to a realistic shot than a simple A over B comp; water elements in the air, whether in spray, mist, or clouds, not only occlude light but diffract it. This diffraction effect can be simulated by applying Compound Blur to an adjustment layer between the fog and the background and using a precomposed (or prerendered) version of the fog element as its Blur layer.

This usage of Compound Blur is is detailed further in the next chapter, where it is used to enhance the effect of smoky haze.

13_smokyFlyover.aep features just such an effect of moving forward through clouds. It combines the tracking of each shot carefully into place with the phenomenon of parallax, whereby overlapping layers swirl across one another in a believable manner. Mist and smoke seem to be a volume but they actually often behave more like overlapping, translucent planes—individual clouds of mist and smoke.

Fractal Noise works fine to create and animate thin wispy smoke and mist. It will not, however, be much help if you need to fabricate thick, billowing clouds. Instead of a plug-in effect, all you need is a good still cloud element and you can animate it in After Effects. And all you need to create the element is a high-resolution reference photo—or even a bag of cotton puffs, as were used to create the images in Figure 13.11.

To give clouds shape and contour, open the image in Photoshop, and use the Clone Stamp tool to create a cloud with the shape you want. You can do it directly in After Effects, but this is the kind of job for which Photoshop was designed. Clone in contour layers of highlights (using Linear Dodge, Screen, or Lighten blending modes) and shadows (with Blending set to Multiply or Darken) until the cloud has the look you’re after (Figure 13.12).

Figure 13.12. The elements from Figure 13.11 are incorporated into this matte painting, and the final shot contains a mixture of real and composited smoke.

So now you have a good-looking cloud, but it’s a still. How do you put it in motion? This is where After Effects’ excellent distortion tools come into play, in particular Mesh Warp and Liquify. A project containing just such a cloud animation appears on the disc as 13_smokeCloud.aep.

Mesh Warp lays a grid of Bézier handles over the frame; to animate distortion, set a keyframe for the Distortion Mesh property at frame 0, then move the points of the grid and realign the Bézier handles associated with each point to bend to the vertices between points. The image to which this effect is applied follows the shape of the grid.

By default, Mesh Warp begins with a seven-by-seven grid. Before you do anything else, make sure that the size of the grid makes sense for your image; you might want to increase its size for a high-resolution project, and you can reduce the number of rows to fit the aspect ratio of your shot, for a grid of squares (Figure 13.13).

Tip

Mesh Warp, like many distortion tools, renders rather slowly. As you rough in the motion, feel free to work at quarter-resolution. When you’ve finalized your animation, you can save a lot of time by pre-rendering it (see Chapter 4).

You can’t typically get away with dragging a point more than about halfway toward any other point; watch carefully for artifacts of stretching and tearing as you work, and preview often. If you see stretching, realign adjacent points and handles to compensate. There is no better way to learn about this than to experiment.

I have found that the best results with Mesh Warp use minimal animation of the mesh, animating instead the element that moves underneath it.

Mesh Warp is appropriate for gross distortions of an entire element. The Liquify effect is a brush-based system for fine distortions. 13_smokeCloud.aep includes a composition that employs Liquify to swirl a cloud. Following is a brief orientation to this toolset, but as with most brush-based painterly tools, there is no substitute for trying it hands-on.

The principle behind Liquify is actually similar to that of Mesh Warp; enable View Mesh under View Options and you’ll see that you’re still just manipulating a grid, albeit a finer one that would be cumbersome to adjust point by point—hence the brush interface.

Of the brushes included with Liquify, the first two along the top row, Warp and Turbulence, are most often used (Figure 13.14). Warp has a similar effect to moving a point in Mesh Warp; it simply pushes pixels in the direction you drag the brush. Turbulence scrambles pixels in the path of the brush.

The Reconstruction brush (rightmost on the bottom row) is like a selective undo, reversing distortions at the default setting; other options for this brush are contained in the Reconstruction Mode menu (which appears only when the brush is selected).

Liquify has the advantage of allowing hold-out areas. Draw a mask around the area you want to leave untouched by Liquify brushes, but set the Mask mode to None, disabling it. Under Warp Tool Options, select the mask name in the Freeze Area Masked menu.

Liquify was a key addition to the “super cell” element (that huge swirling mass of weather) for the freezing of the New York City sequence in The Day After Tomorrow. Artists at The Orphanage were able to animate matte paintings of the cloud bank, broken down into over a dozen component parts to give the effect the appropriate organic complexity and dimension.

Many effects, including smoke trails, don’t require particle generation in order to be re-created faithfully. This section is included less because the need comes up often and more to show how, with a little creativity, you can combine techniques in After Effects to create effects that you might think require extra tools.

Initial setup of such an effect is simply a matter of starting with a clean plate, painting the smoke trails in a separate still layer, and revealing them over time (presumably behind the aircraft that is creating them). The quickest and easiest way to reveal such an element over time is often by animating a mask, as in Figure 13.15, or you could use techniques described in Chapter 8 to apply a motion tracker to a brush.

The second stage of this effect is dissipation of the trail; depending on how much wind is present, the trail might drift, spread, and thin out over time. That might mean that in a wide shot, the back of the trail would be more dissipated than the front, or it might mean the whole smoke trail was blown around.

One method is to displace with a black-to-white gradient (created with Ramp) and Compound Blur. The gradient is white at the dissipated end of the trail and black at the source (Figure 13.16a); each point can be animated or tracked in. Compound Blur uses this gradient as its Blur Layer, creating more blur as the ramp becomes more white. Another method, shown in Figure 13.16b, uses a different displacement effect, Turbulent displace, to create the same type of organic noise as in the preceding cloud layers.

Figure 13.16a and b. To dissipate a smoke trail the way the wind would, you can do so using a gradient and Compound Blur, so that the smoke dissipates more over time, or using the Turbulent Displace effect that, like Turbulent Noise, adds fractal noise, using it to displace the straight trails from Figure 13.15.

What is wind doing in this chapter? You can’t see it. Nevertheless, a static environment is rarely believable if it’s not the surface of the moon, and because your job is to help the viewer suspend disbelief, you may have to consider adding the influence of wind to your scene.

The fact is that most still scenes in the real world contain ambient motion of some kind. Not only objects directly in the scene, but reflected light and shadow might be changing all the time in a scene we perceive to be motionless.

As a compositor, you always look for opportunities to add to them in ways that contribute to the realism of the scene without stealing focus. Obviously, the kinds of dynamics involved with making the leaves and branches of a tree sway are mostly beyond the realm of 2D compositing, but there are often other elements that are easily articulated and animated ever so slightly. Successful examples of ambient animation should not be noticeable, and they often will not have been explicitly requested, so it’s an exercise in subtlety.

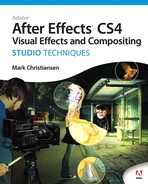

To make it easier on yourself, look for elements that can be readily isolated and articulated; you should be able to mask the element out with a simple roto or a hi-con matte if it’s not separated to begin with. Look for the point where the object would bend or pivot, place your anchor point there, then animate a gentle rotation. 13_ambientAnim.aep (on the disc) offers a simple animation of the arm of a street-light, held out from the background. A little warp on the clouds behind it, and this still image could convincingly be a brief moving shot (Figure 13.17).

Close-Up: Primary and Secondary

Primary animation is the gross movement of the object, the movement of the object as a whole. Secondary animation is the movement of individual parts of the object as a result of inertia. So, for example, a helicopter crashes to the ground: That’s the primary animation. Its rotors and tail bend and shudder at impact: That’s the secondary animation. For the most part, in 2D compositing, your work is isolated to primary animation.

You also have the option of acquiring and adding elements that indicate or add to the effect of wind motion. Figure 13.18 is an element of blowing autumn leaves shot against a black background for easy removal and matting; granted, you could add an element this turbulent only to a scene that either already had signs of gusts in it or that contained only elements that would show no secondary motion from wind whatsoever.

You might want to create a “dry for wet” effect, taking footage that was shot under clear, dry conditions and adding the effects of inclement weather. Not only can you not time a shoot so that you’re guaranteed shooting in a storm (not in most parts of the world, anyhow), but wet, stormy conditions limit shooting possibilities and cut down on available light. Re-creating a storm by having actual water fall in a scene is expensive, complicated, and not necessarily convincing.

I like to use the Trapcode Particular effect (demo on the book’s disc) for the particles of accumulating rain or snow. This effect outdoes After Effects’ own Particle Playground for features, flexibility, and fast renders. As the following example shows, Particular is good for more than just falling particles, as well.

Study reference photographs of stormy conditions and you’ll notice some things that they all have in common, as well as others that depend on variables. Here are the steps taken to make a sunny day gloomy (Figure 13.19):

Replace the sky: placid for stormy (Figure 13.20a).

Adjust Hue/Saturation—LA for Dublin—to bring out the green mossiness of those dry hills, I’ve knocked out the blues and pulled the reds down and around toward green (Figure 13.20b).

Exchange Tint—balmy for frigid—a bluish cast is common to rainy scenes (Figure 13.20c).

Fine-tune Curves—low light for daylight—aggressively dropping the gamma while holding the highlights makes things even moodier (Figure 13.20d).

That’s dark, but it looks as dry as a lunar surface. How do you make the background look soaked? It seems like an impossible problem, again, until you study reference. Then it becomes apparent that all of that moisture in the air causes distant highlights to bloom. This is a win-win adjustment (did I really just type that?) because it also makes the scene lovelier to behold.

You can simply add a Glow effect, but it doesn’t offer as much control as the approach I recommend.

Bring in the background layer again (you can duplicate it and delete the applied effects, Ctrl+Shift+E/Command+Shift+E).

Add an Adjustment Layer below it and set the duplicated background as a Luma Matte.

Use Levels to make the matte layer a hi-con matte that isolates the highlights to be bloomed.

Fast Blur the result to soften the bloom area.

On the Adjustment Layer, add Exposure and Fast Blur to bloom the background within the matte selection.

Figure 13.20e shows the result; it now looks like a wet, cold day, but where’s the rain?

Particular contains all the controls needed to generate custom precipitation; it contains a lot of controls, period. A primer is helpful, to get past the default animation of little white squares emanating out in all directions (click under Preview in Effect Controls to see it). To get started making rain, create a comp-sized 2D solid layer, apply Particular, and

Twirl down Emitter and set an Emitter Type. For rain I like Box so that I can easily set its width and depth, but anything besides the default Point and Grid will work.

Set Emitter Size to at least the comp width in X, to fill the frame.

Set Direction to Directional.

Set X Rotation to −90 so that the particles fall downward.

Boost velocity to go from gently falling snow speed to pelting rain.

You might think it more correct to boost gravity than velocity, but gravity increases velocity over time (as Galileo discovered) and rain begins falling thousands of feet above; however, this is not something you need to replicate, as no one will know the difference.

You do, however, need to do the following:

Move the Emitter Y Position to 0 or less so that it sits above frame.

Increase the Emitter Size Y to get more depth among those falling particles.

Crank up the Particles/sec and Physics Time (under Physics) to get enough particles, full blast from the first frame.

If the particles are coming up short at the bottom of frame, increase the Life setting under Particle.

Enable motion blur for the layer and comp to get some nice streaky rain (Figure 13.21).

Figure 13.21. In the “good enough” category, two passes of rain, one very near, one far, act together to create a watery deluge. Particular could generate this level of depth with a single field, and the mid-ground rain is missing, but planes are much faster to set up for a fast-moving shot like this. The rain falls mainly on two planes.

From here, you can add Wind and Air Resistance under Physics. If you’re creating snow instead of rain, you might want to customize the Particle Type, even referring to your own Custom layer if necessary for snowflakes.

What is the color of falling rain? The correct answer to this zen koan-like question is that raindrops and snowflakes are translucent. Their appearance is heavily influenced by the background environment, because they behave like tiny falling lenses. They diffract light, defocusing and lowering the contrast of whatever is behind them, but they themselves also pick up the ambient light.

Therefore, on The Day After Tomorrow our crew found success with using the rain or snow element as a track matte for an adjustment layer containing a Fast Blur and a Levels (or Exposure) effect, like a reflective, defocused lens. This type of precipitation changes brightness according to its backlighting, as it should. You may see fit to hold out specific areas and brighten them more, if you see an area where a volumetric light effect might occur.

The final result in Figure 13.19b benefits from a couple of extra touches. The rain is divided into multiple layers, near and far, and motion tracked to match the motion of the car from which we’re watching this scene. Particular has the ability to generate parallax without using multiple layers, but I sometimes find this approach gives me more control over the perspective.

Because we’re looking out a car window, if we want to call attention to the point of view because the next shot reverses to an actor looking out this window, it’s only appropriate that the rain bead up. This is also done with Particular, with Velocity turned off and Custom particles for the droplets.

And because your audience always can tell when you have the details wrong, even if they don’t know exactly what’s wrong, check out Figure 13.22 for how the droplet is designed.

Figure 13.22. It looks jaggy because you don’t want particles to be any higher resolution than they need to be, or they take up massive amounts of render time. There are two keys to creating this particle: It uses the adjusted background, inverted, with the CC Lens effect to create the look. Look at raindrops on a window sometime and notice that, as little lenses, they invert their fisheye view of the scene behind them.

Once again, it is attention to detail and creative license that allow you to simulate the complexities of nature. It can be fun and satisfying to transform a scene using the techniques from this chapter, and it can be even more fun and satisfying to design your own based on the same principles: Study how it really works, and notice details others would miss. Your audience will appreciate the difference every time.

The next chapter heats things up with fire, explosions, and other combustibles.