IN THIS CHAPTER

Configurations, also known as simply configs, are variations of a part in which dimensions are changed, features are suppressed (turned off), and other items such as color may also be controlled. Configurations enable you to have these variations within a single part file, which is both convenient and efficient.

This chapter deals only with part configurations, but you should be aware that assemblies can also have configurations. Assembly configurations can use different part configurations, among other things. This will mean more to you as you learn about part configurations.

Note

Assembly configurations are discussed in Chapter 14.

One example of the use of configurations is Toolbox. By default, Toolbox uses configurations to create many sizes of hardware within a single part file. For example, the Socket Head Cap Screw is a single part in Toolbox that contains hundreds of sizes. You can change the size by simply varying the dimensions of the existing features. Toolbox parts also have features that you can turn off and on (suppress and unsuppress, respectively), particularly those related to thread representation (swept versus revolved versus cosmetic). Changing dimensions and suppressing or unsuppressing features are the most commonly used techniques that are available through configurations.

With every new release of SolidWorks software, it seems that there are new items that become "configurable," that is, able to be driven by configurations. Configurable items for parts include the following:

Feature dimensions, driving/driven state

Suppression of features, equations, sketch relations, and end conditions

Which sketch plane is by a sketch

Configuration-specific custom properties

Part, body, feature, and face colors

Derived configurations

The ability to assign properties such as mass and center of gravity

Configuration of base or split parts

You can work with configurations in one of two ways: either manually or through a design table. I describe the manual method first, to give you a good understanding of how to intervene with configs the manual "old-fashioned" way when you need to. Design tables are a fantastic way to organize and manage config data and options, but they also require a bit of syntax, and so I will describe them in a separate section later in this chapter.

Tip

You can split the FeatureManager interface into two by dragging the splitter bar at the top of the panel. This is a very useful function that allows you to see the FeatureManager in the upper panel and the PropertyManager or ConfigurationManager in the lower panel.

Each part has a default config named "Default." There is nothing special about this config; you can rename it and even delete it. There must always be at least one config in the tree, and you cannot delete the current configuration. If you would like to remove a config, then you need to switch to another config first, and then delete it.

In relation to assembly configurations, you cannot delete a config if it is being used in an assembly that is open and resolved. In order to delete a config such as this, you need to either close the assembly or change the part config used in the assembly.

If you try to delete a configuration being used by an open assembly, SolidWorks simply gives the message "None of the selected entities could be deleted" without explanation.

If you delete a configuration of a part that is used in an assembly, but the assembly is not currently open, the next time the assembly is opened it issues the message "The following component configurations could not be found . . . . If the configuration was renamed the same configuration will be used, otherwise the last active configuration will be substituted for each instance."

As you can see, a configuration that is simply renamed is dealt with differently than a configuration that is deleted. In any case, you need to be careful when dealing with parts with configurations that are used in an assembly.

Note

Many users get into the habit of clicking out of any error, warning, or message box that comes up, often without reading what it has to say. It is important to read error and warning messages when they come up. Some of them, such as the configuration message shown previously, are vitally important to the integrity of your design data. They are sometimes actually useful.

You can delete groups of configs by window select, Shift-select, or Ctrl-select in the ConfigurationManager. You can also use the RMB menu, much like regular features in the FeatureManager.

In the ConfigurationManager, configs are listed alphabetically, not in the order in which they are created. This has several advantages, especially when you have a large number of configs. For example, if configs are named by size in a part that you are working with, then when selecting a configuration, you can type in a number, and the selection scrolls to that place in the list of configs. This makes it easier to select the one you are looking for, much the same as it works in Windows Explorer.

This alphabetized order is significant because many other sections of the SolidWorks interface are not alphabetized, which causes problems when you are searching for items in larger lists. Sections that are not alphabetized include Help/Contents, Files Of Type lists in Open and Save dialog boxes, and the Tools/Options/File Locations, Entity Color list. If you are inclined to send in an Enhancement Request, alphabetization is one topic that would benefit everyone and should be fairly easy for SolidWorks to implement.

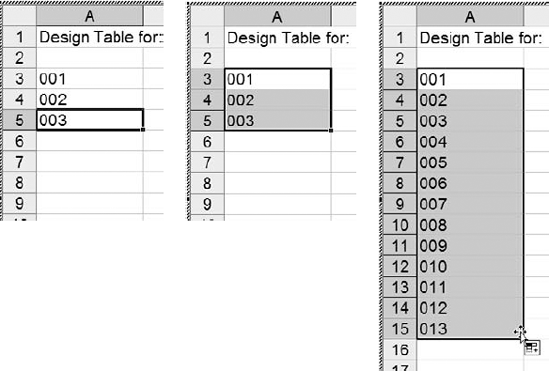

In order for this sorting and alphabetization to work, you must first name the configs properly. For example, if you have a list of sizes or config names from 1 to 100, then you should use 001, 002...100 as your syntax. This makes the config names easier to browse and type in. Syntax becomes most important when you place a part with many configs into an assembly, because you must select a config from the list, and typing in the first few numbers is often faster and easier than scrolling to it.

Note

The CD-ROM contains a part called Chapter 10 Config Names.sldprt, which illustrates proper naming and alphabetization.

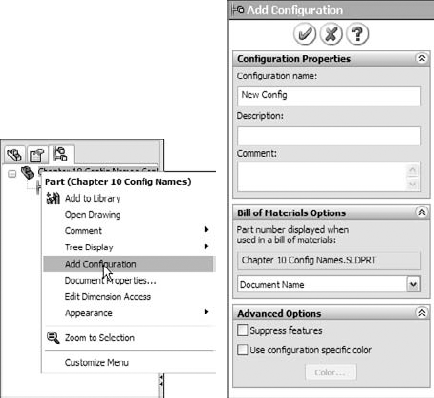

To understand this technique better, you can open the part called Chapter 10 Config Names.sldprt from the CD-ROM, split the FeatureManager area, and change one of the panes to display the ConfigurationManager. Click one of the configuration names, and type in a number between 001 and 100. The highlight scrolls to the number that you typed in. Thoughtful selection of the configuration names can save you and your coworkers a lot of time when you need to insert select configs into an assembly. Figure 10.1 shows this arrangement.

Note

The splitter bar and other portions of the FeatureManager interface appear in Chapter 2.

Within a part file, to change the display from one configuration to another, you must first switch to the ConfigurationManager panel, and then either double-click the desired config or RMB click it and select Show Configuration.

Alternatively, you can RMB click the config in the ConfigurationManager and select Show Preview, as shown in Figure 10.2. A small preview thumbnail displays in the PropertyManager panel. However, not all configurations will have previews. For example, in a part with many configs that have been generated automatically by a design table, the configurations may not have previews because the config itself has never actually been rebuilt. Previews exist only when the configuration has been activated once, the image on the screen generated, and the part then saved. SolidWorks stores both the body (geometry) and the preview image of the part so that next time you access the configuration, the software does not have to rebuild everything again.

You can even select a configuration while opening a file. This allows you to save time by avoiding two model rebuilds. To take advantage of this option, you must use the File

You can create configs manually or through Excel-driven design tables. Design tables are extremely useful for situations where there are more than a few configs, or more than a few items are being controlled. You should use design tables because they keep things very organized within the spreadsheet grid.

For now, I am going to focus on creating and manipulating configs manually so that you can become familiar with them without also worrying about Excel and design table syntax.

The name of the config is important mainly for quick access and organization purposes. The configuration description is also important, because it can display in the ConfigurationManager, and even in the Assembly tree. This is important when the name of the config is numerical rather than descriptive, and you would like to also have a description but not include it in the name. The config description can also appear in place of the filename in the Assembly tree display. I discuss this in more detail in Chapter 12. Config descriptions can be driven manually through the Configuration Properties dialog box or through a design table if you have many configs to manage. You can display config descriptions through the RMB menu, as shown in Figure 10.5.

I discuss the Bill Of Materials options in Chapter 24, but the option is set in the Configuration Properties to use the filename, the configuration name, or a custom name that the user specifies. You can save this setting with a template. Control over configurations is achieved through the combination of the Configuration Properties and the Advanced Options, which are discussed next.

Note

Although you can change the preferred settings at any time, it is definitely a best practice to make a template early on when you are using SolidWorks to model parts. SolidWorks remembers the Bill of Materials options and Advanced options that you set for the Default configuration and uses them in document templates. This is true for both part and assembly templates.

The two advanced configuration options are found in the bottom panel of the Configuration Properties PropertyManager. Suppress Features and Use Configuration Specific Color are the two options available. While the second option is self-explanatory, the first one is not, and often catches new and even experienced users off guard.

Suppress Features refers to how inactive configurations should handle new features. For example, if you have two configs, 1 and 2, and config 1 is active and you add a new Fillet feature, then what happens to that feature in config 2? If this option is turned on, then the new features are suppressed. If it is turned off, then the new features will be unsuppressed when the inactive configs are activated. This creates a much bigger challenge for manually created configurations than for design table-driven configs because changing suppression states for several features across multiple configs is much easier in a design table than in manual config management.

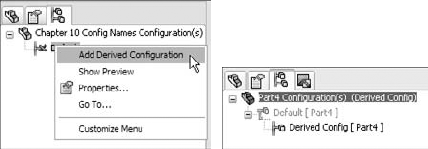

Derived configurations are configs that are dependent on other configs. You can create them from the RMB menu on a configuration instead of on the top level in the ConfigurationManager, and they appear indented underneath the parent config. Figure 10.6 shows the RMB menu and the position of the derived config in the tree.

Derived configurations maintain the same values and properties of the parent config unless you break the link to the child config by explicitly changing a value in the child config. For all other values, the child config value changes when the parent config value changes.

One very nice application of derived configs is to use them for simplified configurations, and set the properties so that any features that are added to the parent config are also added to the derived config. You can do this by setting the Advanced Option Suppress Features to Off. This causes the derived config to inherit only features that are added to the parent, and not to other configs. The simplified configs are used for FEA, making drawings of models where all of the edge breaks have actually been modeled. They are also used for the reverse (a complex config rather than simple) to have a config that includes fillets for rendering purposes that are otherwise not there. You can also create and maintain derived configs using design tables, which are discussed in the next section.

A long-standing dispute has raged over the effects of file size on speed. Here are the facts: When SolidWorks creates a configuration, it stores information about the 3D geometry and a preview thumbnail of the configuration inside the part file. This makes it faster to access the configuration the next time because it has only to read the data, rather than read other data and then recalculate the new data. As a result, saving the stored data allows you to avoid having to recalculate it.

Note

Appendix A contains a section on Data Management that has several options for dealing with data and large file sizes.

File size has a negative effect on speed when you are sending data across the Internet or working across a network. If the data is on your hard drive, then storing data instead of calculating it offers a big benefit.

Note

SolidWorks 2007 Service Pack 1 has a fix associated with it that takes advantage of a new hotfix from Microsoft that removes shadow data from files, and may reduce the size of SolidWorks files to one-half or even one-quarter of their original size. See the SolidWorks Customer Portal and the Microsoft support site for details regarding Microsoft Knowledge Base article 919880. The Microsoft hotfix files can be found on the SolidWorks support site. Files with many configurations are supposed to derive the most benefit from the combination of this service pack and hotfix.

Controlling dimensions with configurations is simple. You need only three things to start: one dimension and two configurations. Because you already know how to create these elements, you are ready to start. Configurations require that you spend some time developing "design intent" for parts. Configurations drive changes in models, and if they are improperly modeled, then configurations will cause feature or sketch failures.

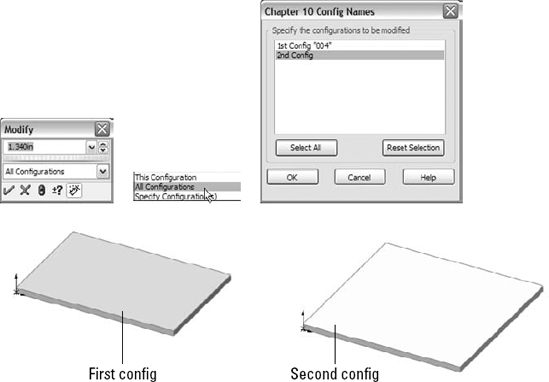

I will start with the example of a simple block. A fully dimensioned block has three dimensions. Make sure that you have manually created at least two configurations. Double-clicking the model brings up all of the dimensions, and double-clicking one of the dimensions brings up the familiar Modify dialog box. Or almost familiar, I should say; Figure 10.7 shows that there is a small difference in the new Modify dialog box. It now has a drop-down list where you can specify whether this change applies only to this config, to all configs, or to specified configs. If you select specified configs, then the dialog box on the right in Figure 10.7 appears, where you can select which configs this dimension change applies to.

Once you are finished, you can toggle back and forth between the configs by double-clicking each of the configs in the ConfigurationManager. Although this is simple, if you forget to change the drop-down list from the All Configurations setting to either the This Configuration or the Specify Configuration(s) setting, then you apply the change to all of the configurations. This example shows that building a configuration manually is fine for a few simple changes, but it can become unwieldy if you are changing more than a few dimensions in this way. You would then have to remember which dimensions were changed to what. As you can see, using design tables is a better method for multiple dimensions.

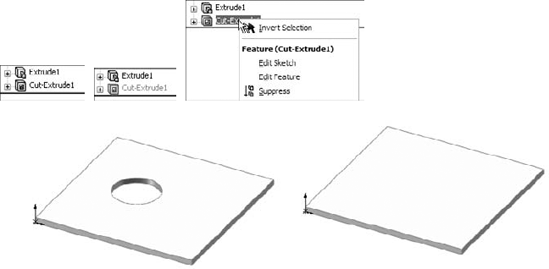

In addition to the Suppress toolbar button, you can also use the Unsuppress and Unsuppress with Dependents features. When you suppress a feature, any feature that is dependent on it is also suppressed. If you then use the Unsuppress feature, it unsuppresses only the feature itself. However, Unsuppress with Dependents brings back all of the dependent features, as well.

Note

Suppressing complex features is a great way to improve performance. Experienced users often create a configuration of a part that they use as a simplified config, where patterns, fillets, and extruded text features are suppressed. This becomes more important as you start working with assemblies.

Generally, SolidWorks users employ a combination of these methods, mainly because configurations are not usually started on a complete model; they are often added when the model is still in progress, and so features are added after the users create the configurations.

Figure 10.8 to the left side of the image shows a feature that is both unsuppressed and suppressed in the tree. The text and icon for the suppressed feature are grayed out. You can suppress features from the RMB menu on the feature, from the Edit menu, or through a tool on a toolbar. The Suppress button is not on a toolbar by default, but you can find it in the Tools

When you control suppression in manually managed configurations, you will often need to switch between configs to ensure that you have applied the correct dimensions and suppression scheme. As a result, manual configuration management is not a desirable method.

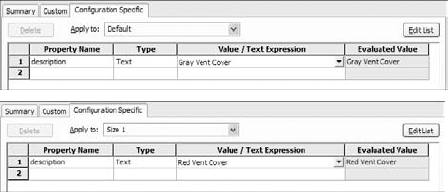

Custom properties fall into a category of model data called metadata, which is text-based information. This metadata is meant for any text-based data that you would like to accompany the part, such as description, material, vendor, vendor part number, price, or even cost. Several reasons may compel you to use custom properties, including search criteria for a Product Data Management system, automatically filling out drawing title blocks, or adding information to the Bill of Materials.

When you are using custom properties with configurations, you must use the Configuration Specific Custom Properties interface, which enables you to have custom properties that change with each configuration. This is useful for situations such as different part numbers for configurations, and many other situations that are limited mostly by your use of configs.

The interface for managing custom properties manually is shown in Figure 10.9. You can access this dialog box through menus at File

You can also link custom properties to mass properties, model dimensions, link values, and global variables by selecting from the drop-down list under the Value/Text Expression column, which appears when you select a cell in the column, as shown in Figure 10.9. To link a custom property to a model dimension, simply place the cursor in the Value/Text Expression box that you want to populate, and click a dimension in the graphics window. Again, managing this data for a single config or only a few configs is easy enough; however, it can quickly become unwieldy, which is where using design tables can make a huge difference.

Face, feature, body, and part colors as well as materials are also configurable. Just switch to the configuration you want to control, and make the changes.

Note

New in SolidWorks 2007 sp1 is a button in the Color Properties dialog box labeled Remove All Colors. You do not need to have anything selected for this function to work, but it only works for the current configuration. It removes all colors that are assigned to anything but the part level (the part needs to have a color assigned to it). In the past, users required a macro to eliminate special colors.

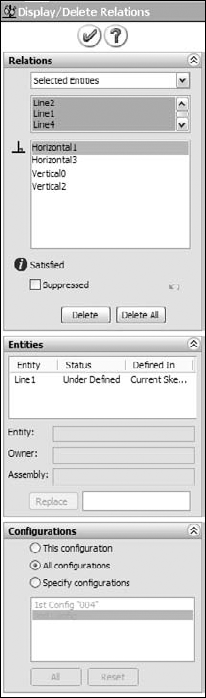

You can individually suppress or unsuppress sketch relations using configurations. Figure 10.10 shows the Display/Delete Relations PropertyManager interface, at the bottom of which is the Configurations panel. To suppress a relation, select it from the list and select the Suppressed option in the Relations section above the Delete buttons.

Tip

This is another situation where Delete is not used as an editing option. Using this technique, you can save sketch relations, or activate different sets of relations in different configs; this technique allows a single sketch to react to changes differently.

You cannot configure the Offset distance in the From option for extrudes, but you can configure the sketch plane for the sketch that is used in the feature. The Sketch Plane PropertyManager interface expands when configurations are present, as shown in Figure 10.11.

Tip

Another way to change the sketch plane is to put the sketch on an offset plane or a plane that can otherwise be driven by a dimension (for example, using reference sketch geometry). Actually moving a sketch to another plane can cause the sketch to rotate or flip. Moving the plane it is on is a better option that does not cause the sketch to rotate or flip.

Warning

Changing sketch planes indiscriminately can have serious consequences for your model. "Face/Plane Normals" sometimes point in different directions, and can cause a sketch to flip, rotate, or mirror when you change it from one plane to another. One strange result is that changing it back to the original location can cause the sketch to flip again, but in a different way so that it does not go back to its original location/orientation. As a result, every time you change the configuration, the sketch could appear in a new and unexpected location or orientation.

Note

Inserted parts are discussed in detail in Chapter 28, which describes master model techniques.

Inserted parts use one part as the starting point for another part. The inserted part sits as a feature in the FeatureManager of the child part. The features of the original inserted part are not brought forward; only the finished solid body or bodies, select surface bodies, planes, and cosmetic threads are brought forward. It is a major point of contention for many people that you should also be able to bring forward sketch data, but this option is not available at this time (however, if you have a bookmark to that enhancement request site, you may want to request this feature).

The role of configurations with inserted parts is that the configuration of the inserted part can be controlled from the child component. For example, you may have designed an engine block for an automobile. This engine block is a casting, and using configurations, you have both the six-cylinder and the eight-cylinder blocks in a single-part file. This model represents the "as cast" engine block. The next step is to make the block with all of the secondary machining operations, such as facing mating surfaces, reaming cylinders, drilling and tapping holes for threaded connections, and so on. As a result, the as-cast part is inserted into the as-machined part, and the configuration is selected before you add the cut features. As the name suggests, you add inserted parts through the menus using Insert

The interface for assigning the configuration is shown in Figure 10.12. Simply RMB click the inserted part feature and select List External References.

Library features can have configurations, and they carry those configurations with them into the part in which they are placed. Unfortunately, part configs cannot reference different library feature configs.

Note

Chapter 17 discusses the Hole Wizard, and Chapter 18 discusses library features.

Configurations for library features are created in exactly the same ways that configurations are created for other parts. The technique for saving the configs to the library feature is discussed in Chapter 18.

As important as it is to know what you can do, it is equally important to know what you cannot do. The following is a list of items that are not configurable. Although this list is not complete, it contains many of the more relevant items that cannot be configured:

Hole Wizard holes (although there is a workaround: dimensions can be configured)

Library feature configs

Blocks

Extrude direction or From Offset dimension or direction

Most of the values in features such as Deform, Freeform, and Twist

Hide/Show state of a body

In addition to describing some of the basic concepts involved with configurations, the first part of this chapter has offered reasons for using design tables. For example, while manual configuration management can be haphazard, and is highly prone to mistakes, design tables lay everything out in an Excel spreadsheet. Although many new users ask whether they can use a different replacement spreadsheet program, you must use Excel.

Note

The versions of Excel that are supported by SolidWorks for design tables are XP, 2000, and 2003. Although Excel 97 may still work, Microsoft no longer supports that product.

Excel is a format that is easy to read and print out, and even non-SolidWorks users can understand and work with it. Although there is some special syntax that you need to use with design tables, for most uses, SolidWorks can create the syntax automatically for you, and so there is a minimum of manual data entry. If you are careful to name dimensions, features, and configurations properly, design tables should be easy to understand and manage. Excel can also color cells, rows, and columns in such a way that large amounts of tabulated data are easier to sort through. In addition, because design tables use Excel, they can also use Excel's equations.

Note

When using equations and design tables, it is considered best practice to name dimensions, sketches, features, and other configured items. However, it is not recommended to mix design tables with SolidWorks equations. Besides the fact that Excel equations are far more sophisticated than those of SolidWorks, driving dimensions from too many locations can be confusing when you edit the part after you have forgotten the details of how the part was built.

It is a great idea to document design intent using comments in the features or the Design Journal. You should also add comments to design tables as needed.

Just because something can be configured does not necessarily mean that it can also be driven by a design table. Here is a small list of items that fit into this category:

Sketch plane configuration

Suppressed sketch relations

Suppressed dimensions (suppressed dimensions become driven dimensions)

However, the good news is that there are many items that can be driven by a design table. Table 10.1 lists these items, along with their associated syntax.

Table 10.1. Items That Can Be Driven by a Design Table

Item | Syntax (Goes in Column Header) | Possible Values (Goes in Field Cell) | Default Value If Field Is Blank |

|---|---|---|---|

Configs of Inserted Parts | $configuration@<part name> | <config name> | not evaluated |

Configs of Split Parts | $configuration@<split feature name> | <config name> | not evaluated |

Comment Column | $comment | comment text | blank |

Configuration Description | $description | description text | <config name> |

BOM Part No. | $partnumber | $d, $document = document name $p, $parent = parent config name $c, $configuration = config name <text> = custom name | config name |

Feature Suppression State | $state@<feature name> | suppressed, s unsuppressed, u | present suppression state |

Dimension Value | dimension@<feature name> dimension@<sketch name> | allowed numerical values | not evaluated |

Parent Config (creates a derived config) | $parent | parent config name text | not evaluated |

Config Specific Custom Property | $prp@<property name> | property name text | not evaluated |

Equation State | $state@<equation number>@equations | suppressed, s unsuppressed, u | unsuppressed |

Light Suppression State | $state@<light name> | suppressed, s unsuppressed, u | unsuppressed |

Sketch Relation Suppression | $state@<relation name> @<sketch name> | suppressed, s unsuppressed, u | unsuppressed |

User Notes (same as comment) | $user_notes | Text | blank |

Part or Feature Color | $color $color@<feature name> | see SolidWorks Help, Colors, Parameters in design tables | 0, black |

Assigned Mass | $sw-mass | allowed numerical values | value from Mass properties |

Assigned Center of Gravity X, Y, Z Coordinates | $sw-cog | allowed numerical values in the format of x, y, z | value from Mass properties |

Dimension Tolerance | $tolerance@<dimension name> | see SolidWorks Help, Tolerance Keywords and Syntax in Design Tables | none |

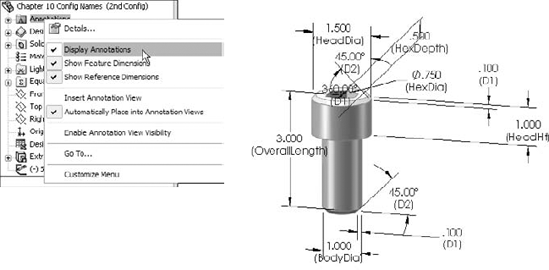

When you prepare to create a design table, you generally need to give appropriate names to dimensions, sketches, and features. Remember that while the feature is the most visible item and the easiest to rename, most of the dimensions probably belong to the sketch, which you may also need to rename. Names should reflect the function or location of the item. It is a good idea to show dimension names when renaming items (remember that you can show dimension names by turning on the option at Tools

You can use one of the following three techniques to add a design table to a SolidWorks part:

Insert Blank Design Table: This method starts from a blank template that contains the underlying framework, but no values.

Auto-create Design Table: This method populates the new design table with any existing configurations and items that are different between the configs.

From File: This method allows you to create a design table externally and then import it.

Although I prefer the Auto-create method, it is most appropriate for when you have existing configurations. The From File method is best when a design table has been exported from another part, saved externally, and brought into the current part. For the following example, I am using the Insert Blank Design Table method.

Note

If you would like to follow along with these steps to create the design table, you can use the part from the CD-ROM with the filename Chapter 10 DTstart.sldprt.

Figure 10.14 shows the results of starting with the new blank design table. You may notice that the window title bar at the top says SolidWorks, but the toolbars look a lot like the Excel interface. This is because Excel is actually running inside of SolidWorks. Clicking outside of the Excel window can cause the Excel window to close, although there are several items outside of the Excel window that you can select without the window closing, such as features in the FeatureManager and dimensions in the graphics window. You can also rotate and pan the view in the graphics window without closing the Design Table window. If you are very careful, you can also drag the thin hatched border of the Excel window to adjust its size or location.

Design Tables also can be edited in a separate window, which makes editing easier, but makes adding dimension and feature names more difficult. To edit the table in its own window, RMB on the Design Table in the FeatureManager and select Edit Table In New Window.

Figure 10.14. The interface where you can create the design table, and the resulting blank design table

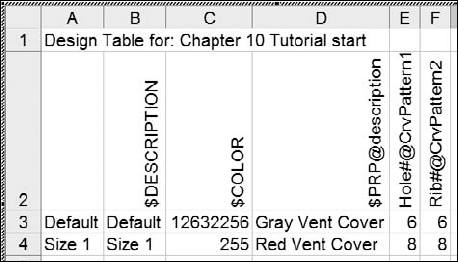

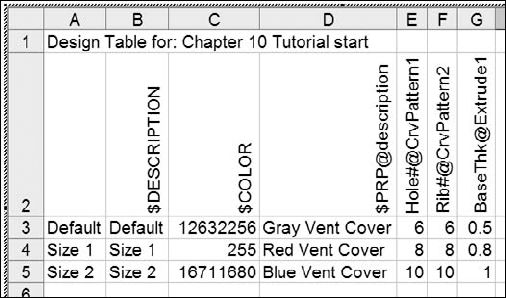

Figure 10.15 shows a fully developed design table, with some complexity. Although your first design table does not need to be this complex, this example demonstrates what you can do with this feature.

The config names go in the first column, and the feature or property names go in the second row. The first row is reserved for the name of the table. All of this is automatically set up by SolidWorks.

Note

Because you are actually working in Excel when working with design tables, you can use Excel formatting, which is how the text in Figure 10.15 is rotated 90 degrees for the column headers. (To rotate text in a table, RMB click the cell, group of cells, or row; select Format Cells; and then select the Alignment tab).

In our new design table, the next step is to type in some configuration names. Because you are working in Excel, all of the fill functionality is available. In the example shown in Figure 10.16, I have typed in the first three values of 001, 002, and 003, then window-selected the cells, and dragged the fill handle on the selection window to fill the number pattern to populate a larger area. To find more information about this technique, look for Fill or Automatically Number Rows in the Excel Help files.

The next step is to fill in some feature and dimension names in the second row. The first thing that you do is to suppress the HexDrive feature. To make this the first feature in the list, click in cell B2, and then double-click the HexDrive feature in the FeatureManager. The name of the feature and its current suppression state are added to the design table with all of the necessary syntax and correct spelling.

To rotate the text in this row vertically, RMB click row number 2, select Format Cells, click the Alignment tab, and turn the orientation to 90 degrees. The word unsuppressed displays with all capitals and fully spelled out, while all you need is a U or an S. Replace the word with an S, and double-click the line between the column heading letters B and C at the top of the Excel window, to condense column B as much as possible. Alternate the rest of the rows between Us and Ss to either suppress or unsuppress the HexDrive feature in various configurations. Figure 10.17 shows the current state of the design table.

Close the Design Table window, and click OK on the message box that lists the new configurations created by the Design Table. Now split the FeatureManager, set the lower pane to the ConfigurationManager, and double-click some configurations. Notice that in the configs where you specified an S, the HexDrive is suppressed, and no longer appears in the model.

You can now add a dimension to the design table. To add a dimension, it is most convenient to display the dimensions on the screen at all times. To show all of the dimensions in the part, RMB click the Annotations folder in the FeatureManager and select Display Annotations. If the dimensions do not display, then you may have to go back and select Show Feature Dimensions. Arrange the dimensions so that you can clearly see them all, as shown in Figure 10.18.

To display the design table again, locate it in the FeatureManager list, just below the Origin, RMB click it, and select Edit Table. Editing the feature changes the settings used for the design table. Edit Table in New Window is an option that we will use later because it simplifies many things; however, for now, the Edit Table option makes it easiest to add new items to the design table.

Note

If a window appears with the name Add Rows and Columns, just click OK for now. This window lists parameters that have changed in its lower pane, and it is asking you if you would like to add any of the changed parameters to the design table. If you would like to add them, just select the parameter in the lower pane and click OK. If not, just click OK.

If the design table displays on top of your model, you can either move the model or move the design table. Moving the design table is a bit tricky, and involves dragging the striped-line border of the Excel window; remember not to grab it at the corners or midpoints, because this will simply resize it. If you click inside the border, nothing happens. If you click outside of the border, the Excel window closes. Moving the model may be easier. To do this, just Ctrl-drag in blank space in the graphics window; it pans the display so that you can see the part dimensions.

With cell C2 selected, or whatever the next available cell is in the second row, double-click the OverallLength dimension in the graphics window. SolidWorks adds the proper syntax to the design table, along with the current value for the first configuration in the list. Fill in values for the rest of the configurations. These values can then be calculated in Excel using any of the available techniques.

Exit the design table and toggle through the various configurations to see their different lengths. These examples should get you started on more complex configurations and design tables. Any dimensions that are controlled by the design table (and that are therefore locked) display in pink on the screen.

Figure 10.14 shows the PropertyManager for design tables. After you have created the table, you can edit the table settings by RMB clicking the table and then selecting Edit Feature. Edit Feature enables you to edit the settings for the table only; it does not enable you to edit values within the table.

By selecting the From File source option, you can create a design table from an external file; you can also link the table to the external file. When you use the other two options, Blank and Auto-Create, SolidWorks stores the Excel file within the SolidWorks document. Linking to an external file may be useful if you have a non-SolidWorks user who is entering data into the design table, or if a single table controls multiple parts.

The Edit Control panel has two options, which act as a toggle. The Allow Model Edits To Update The Design Table option is self explanatory, as is its opposite, the Block Model Edits That Would Update The Design Table option. If the Allow Model Edits option is selected, and you make a manual change to the model, the next time you open the design table, SolidWorks warns you about the change and that it will update the design table. Likewise, if you try to make a manual change and the Block Model Edits option is selected, you receive a warning that the value cannot be changed.

The Options settings determine the behavior when you are using the Allow Model Edits option and a new item has been configured. For example, the design table may already exist, and you manually add a configuration and suppress a feature.

Configurations that have been added manually are displayed somewhat differently from configs that are being managed by the design table. Figure 10.19 shows the two configurations at the bottom of the tree with square symbols, while the design table configs have Excel symbols.

After you manually add the config and suppress the feature, the next time you open the design table, the Add Rows and Columns dialog box appears. Most users are simply annoyed by this, but that may be because they do not understand what it does or why it appears. In the example shown in Figure 10.20, a new configuration has been manually added; it appears in the Configurations box as Manually Added Config, and in the Parameters box, it looks like a feature named BodyChamf has been either suppressed or unsuppressed manually. The appearance of this dialog box means that SolidWorks is asking you if you would like to include these items in the design table. If so, then simply select the items you would like to add to the design table and click OK. If you do not want to include the items in the design table, then simply click OK or Cancel. If you click OK, then you will not be offered these choices again; if you click Cancel, then the next time you open the table, the dialog box with the same choices will reappear. If you never want to see this dialog box again, then make sure that all of the options in the Options panel shown in Figure 10.14 are turned off.

As mentioned earlier, when you open the design table inside the SolidWorks window, it can sometimes be difficult to work with. One way to handle this problem is to only edit the design table inside SolidWorks when you want to add new features to the column headers, and when adding new configurations or editing the field values, edit the table in a separate window. This option appears on the RMB menu, as Edit Table in New Window. It allows you much more flexibility in resizing the Excel window, changing zoom scale, and other operations, but it does not allow you to double-click a dimension so that it is added automatically to the column header.

Warning

When working on design tables, it is a good idea to avoid conflicts with other sessions of Excel by closing any other Excel windows. The combination of operating Excel spreadsheets inside both SolidWorks and Excel has been known to cause crashes, or the "Server Busy" warning message. If you are diligent about having only one session of Excel active at a time when you are working on design tables (or Excel BOMs), then there is less likelihood of a crash or conflict.

Throughout this book, parts that I use for one purpose may also be interesting for other purposes as well. For example, the part used in this tutorial uses a loft with guide curves where both guide curves are created in the same sketch. The guide curve sketch is made from symmetrical splines where I have used the spline handles to change the shape smoothly and in a controlled way. I have also used a curve-driven pattern to go around an elliptical shape.

Tip

If at some point you decide that you have made mistakes from which you cannot recover, or you would simply like to start over again, you can select File, Reload. This is the same as exiting the part without saving, and then reopening the part to start from the beginning.

To start working with configurations and design tables, follow these steps:

From the CD-ROM, open the part called Chapter 10 Tutorial start.sldprt. Take a moment to become familiar with this part by using the rollback bar to see how it was made. In particular, look at the two patterns, which need to be parametrically linked. Figure 10.21 shows the part.

Manually create a configuration for the part called Size 1. Remember that to create a configuration, you must show the ConfigurationManager tab in the FeatureManager area, and RMB click the name of the part at the top level. It is better to do this by splitting the FeatureManager window and setting the lower pane to the ConfigurationManager.

Set the Advanced option to both Suppress Features and Use Configuration Specific Color (both turned on).

Before closing the Add Configuration PropertyManager, click the Color button on the Advanced Options panel of the Configuration PropertyManager and select a different color for the Size 1 configuration. The color does not change immediately. It will change after you close the PropertyManager.

Turn on the Tools

Double-click the feature CrvPattern1 in the FeatureManager. A number 6 with a D1 under it will appear on one of the holes in the pattern. If you have changed your part to a blue color, then it may be difficult to see, because the text will also be blue.

Change the name of the dimension to Hole# by RMB clicking the dimension and selecting Properties.

Change the value of the number to 8, and be careful to also change the drop-down setting to This Configuration Only instead of All Configurations. If you forget to do this, then you will have to go to the other configuration and set it back to 6.

Click the Rebuild symbol (which resembles a traffic light) to show the changes before exiting the Modify dialog box. Notice that the CrvPattern2 fails after rebuilding CrvPattern1 with eight instances. Click the green check mark icon to exit the Modify dialog box, and then make the same changes to the CrvPattern2, from changing the dimension name and the number of patterned instances to eight (remember to use the This Configuration Only setting). The part should now look like Figure 10.22.

Double-clicking to change configurations now shows a part with a different color and a different number of holes and ribs. After the first change between configurations, the changes should happen quickly because SolidWorks has stored the geometry.

Go to File

Exit the Custom Properties dialog box.

Now that you have made a few changes manually, the following steps guide you through bringing these changes into a design table and using the design table to make additional changes. From the menus, select Insert

Use the striped border to move the window without closing it. This may take some practice. If the window closes, just RMB click the design table in the FeatureManager and select Edit Table. Move the window to a place where you can see the model clearly.

If a cell in the second row of the design table is selected, select a different empty cell that is not in the second row (this prevents data from automatically populating cells until you have the correct data). Now double-click the Extrude1 feature in the FeatureManager. Find the .500'' (D1) dimension on the screen. RMB click the dimension and rename it BaseThk.

Click the next open cell in the second row, and double-click the .500'' dimension that you just renamed. You may have to use the handles at the corners and side midpoints to resize the Excel window to see everything. Add another configuration row and the additional values in the cells, as shown in Figure 10.25. The color number is determined by a formula that you can find in the help section under the topic Color Parameter.

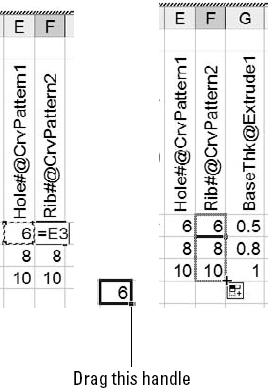

Remember that this part needs to have the number of ribs always equal to the number of holes. This is simple to do in Excel. Click in the first row value for the Rib# number. This is cell F3 in Figure 10.25. Type the equal sign, and then click in the cell to the left, E3. You can also simply type =E3 in this cell. This links the Rib# cell to the Hole# cell.

Use the Window Fill feature by selecting the dot at the lower-right corner of the selected F3 cell and dragging it down to also include cells F4 and F5, as shown in Figure 10.26.

Click in a blank space to exit the design table. Double-click through the configurations in the ConfigurationManager to see the results of your efforts.

Configurations are a powerful way to control variations of a design within a single part file. Many aspects of the part can be configured, while a few cannot. Manually created configurations are useful for making a small number of variations and a small number of configurations, but they become unwieldy when you need to make more than a few variations of either type.

Design tables are recommended because they allow you to more clearly see all of the changes that have been made for all of the configurations. Having the power of Excel available allows you to access many functions that are not shown here, such as using lookup tables and Concatenate functions to build descriptions or configuration names. I will briefly revisit design tables in the section on assembly configurations to expand on the information here, and to incorporate the additional assembly configuration information.