Agile Project Management

Graham Collins, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, University College London

Chapter Outline

Definitions of Success Are Part of the Problem

How Does a Generic Agile Development and Project Run?

Having an adaptable process to development that can respond to rapidly changing economic conditions is one way organisations can compete effectively. Agile project management enhances the ability of teams and organisations to react to these changes. Traditional approaches to project management often entail following a set plan and if there is a divergence from this plan it is often considered the role of the project manager to correct this and ensure no deviations. Agile approaches, however, recognise that goals will inevitably change and that achieving value for the client should be the most important consideration.

It is often the case that during a development process the requirements will have substantially changed. The longer the time interval from requirements gathering to delivery the more likely the client will indicate that what has been developed doesn’t meet their needs. Also it is unlikely that many of the requirements will still be considered important after a few months or even at the start of development. During workshops with clients it often occurs that every participant volunteers at least one requirement, but if after outlining this list there is a voting opportunity for the priority of these requirements it is likely many are not voted for at all. It is not only that the client team needs to see a prototype, often to understand what they truly want, it is also likely that any software developed may change the business processes to such an extent as to make the original requirements even more obsolete.

One way to reduce the risk of development being detached from what is actually required by the client is to provide a more frequent feedback to the client including what is being developed. Agile project management accelerates the feedback cycle and actively involves the customer in the prioritisation of the requirements and design of the product. Delivering a product after 12 or 18 months runs the risk that the business needs have changed or that the client team realises on viewing the software it is not what they actually want. It is better to have a set regular feedback cycle continually prioritising the most valuable functionality and delivering some thread of working software for the client to comment on. Producing a tangible software or product at regular intervals and having a continual communication cycle, involving the client, is at the heart of agile methods.

Traditional planning is typically based on the concept of delivering a project within a set budget within a set schedule. The agile philosophy encompasses delivering as rapidly as possible high value products or software. Ensuring that this delivery benefits from regular feedback enhances this value. It also ensures that within a fixed time the greatest value in terms of the functionality as prioritised by the client is delivered. The shift for both the organisation and the project manager is one from delivery of a project to schedule and budget to one of delivery of the highest value within the time and other constraints set.

It is through a cycle of iterations and release, with continual working software of product developments, that trust is built and the client can see that every release is providing increased functionality and business value.

The Paradox

Managers typically wish to know how much and how long a project will take and yet they still want to have the flexibility to respond to the business environment and embrace innovation. How can we achieve flexibility and respond to change and at the same time follow a plan? The answer is partly in granularity, considering the capabilities at a high level of abstraction for planning and allowing development teams to define specific tasks according to the needs of the project. Agile is inherently measurable because of the clear regular cycles and internal and external measures. At a high level of abstraction these are the regular releases defined by the needs of the project, domain, and agile method, often every 90 to 120 days. Within these there are the iterations of one month or shorter cycles. And furthermore within a day there is the daily cycle identifying what has been delivered, what are the problems, and what will be done next. Within this especially in software development there are cycles that are achieved within even shorter periods by development teams using test-driven development and automated testing techniques.

Definitions of Success Are Part of the Problem

If we measure success in terms of achieving the original specifications, then measuring agile projects that are designed to incorporate changes in goals to achieve maximum business value to the client will bound to be problematic. What is needed is to base measures on what the client considers of value and for this to be updated continually. In agile methods and particularly with the Scrum method this is achieved via the Product Owner who is the client representative on the team. Typically the Product Owner is part of the development team and represents and works closely with the client or client team to determine the most valuable capabilities and constituent features. They will at the start of each iteration be involved in prioritising features from capabilities they have identified into a finer detail of functionality expected from the system. Dependent on the method, the requirements may be in the form of user stories, to gain some idea of how users will use the system. It is through this process that the Product Owner with the development team prioritises the most valuable stories for the coming iteration. This cycle continues so that at any given point the project has delivered the highest value functionality as defined by the client.

One advantage of reducing cycle time is that the team soon learns what is working and what is not and can correct the development as necessary. Another advantage is that valuable working software or products are brought into use earlier, starting to contribute economic benefits, so that the project reaches the breakeven point and provides a return on investment (ROI) sooner.

What Is Agile?

Jim Highsmith (2010) outlines that being agile is not a silver bullet to solving your development or project management problems. He characterizes agile in two statements: ‘Agility is the ability to both create and respond to change in order to profit in a turbulent business environment. Agility is the ability to balance flexibility and stability’ (Highsmith, 2002).

The concept of iterative and incremental development is not new, and developers in the 80s and 90s were designing light methods aimed at involving the development teams and customers in closer collaboration. An alliance of these developers met in Snowbird, Utah, in February 2001 to see if there was anything in common between the various methodologies being used at the time. They agreed on an agile manifesto and values (below) supporting the manifesto. The latest updates to this can be found at www.AgileAlliance.org:

• Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software

• Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer competitive advantage

• Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter time scale

• Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project

• Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done

• The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation

• Working software is the primary measure of progress

• Agile processes promote sustainable development

• The sponsors, developer, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely

• Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility

• Simplicity – the art of maximizing the amount of work done – is essential

• The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams

• At regular intervals the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behaviour accordingly

One of the most important aspects of agile processes is the continual reflection and adaption. Many of these values have also been adopted by agile project management approaches, especially the concepts embedded within one of the methods, Scrum, including set iteration lengths termed sprints, daily stand-up meetings, and reviews, as part of the process. At the end of each sprint, a tangible product is delivered and at the end of a series of sprints, a release, the current working version of the product is released to the customer for detailed review.

Lean

Lean processes are typified by reduced inventories and cycle times. There are many concepts that agile and lean have in common particularly in processes to remove waste and rework. The background to the lean movement can be seen in the Japanese manufacturing sector and also in the Six Sigma quality improvement initiatives. As with many agile methods and approaches some of the ideas have their roots in previous practices.

Grant Rule (2011), during his guest lecture at UCL, 2010, outlined the similar concepts used in the production line techniques of building warships at the height of the Venetian empire, several hundred years prior to the concept of automotive production lines. During this period of expansion, the wooden warships were to protect the trading interest of the Venetians and due to the limited space in the Arsenale the inventory and waste was kept to a minimum and the pressure of conflicts meant that they had to reduce cycle times and release ships to protect their routes and territories as frequently as possible. This would be the equivalent of producing working software frequently to customers. There is evidence of continual improvement in the process although whether this allowed teams time for reflection and self-organisation is highly unlikely.

The importance of frequent releases of software is central in agile project management. This enables feedback from the client to build trust and an effective product that provides the highest value within the given time. As requirements often fit into a profile familiar in Pareto analysis with only 20% of the functions used 80% of the time, then delivering the highest value and functionality first will often be sufficient as many of the additional requirements may be obsolete, seldom used, or need to be changed.

To take full advantage of agile methods lean practices need to be adopted across the organisation (Salloway, Beaver, and Trott, 2010). It is certainly the case that the major challenges in an organisation are often the cultural changes necessary, which include the empowerment of teams and creating an environment of trust to allow the teams to determine their own approach to development.

Agile is not a panacea. There is no set recipe to follow, but there are some patterns that perhaps all projects should follow. One pattern is the idea of time-boxing every aspect of the project cycle. This is not just a defined time but as short as possible time to speed up the feedback and associated learning cycle. This includes the discussions with clients as well as the review meetings.

Two Levels of Planning

Agile techniques encourage planning at two levels of abstraction. The customer or client, represented by the Product Owner, usually has an initial idea for the capabilities of the product being developed. This allows for a high-level capability plan to be developed in which the capabilities can be valued. Dean Leffingwell (2007) suggests a value feature approach in which the features are assigned priority and value, giving immediately some indication of value of the project as well as an approach to track progress in terms of value at a high level.

At an iteration level the capabilities need to be decomposed further into features and stories and prioritised. It is this that gives the second level of tracking and can be achieved in terms of stories and the size estimated in terms of story points. The team then decides how these tasks are broken down and commit at a daily level to delivery of this work.

Terminology

As with any professional practice there is often terminology that may be difficult for the outsider to interpret. In law, Latin phases are often used, although increasingly in other areas such as medicine it appears that the language is converging to more readily understandable terms. A glossary of agile terms can be found in the Guide to Agile Practices http://guide.agilealliance.org/. Perhaps it is that sometimes those not involved in agile project management and development are somewhat perplexed by terms such as Scrum and Planning Poker. Is this some kind of game we are playing? Well, part of the answer is yes, as the highly interactive and collaborative planning process has been termed a ‘game’ by some leading agile proponents (Cockburn, 2002). A game involving the customer at its core and delivering the highest business value within a given period.

How Does a Generic Agile Development and Project Run?

A workshop may be needed to determine the overall process and project management approach. Different agile techniques favour different approaches and use different terms. All outline the need for prioritisation of requirements. In some methods such as Feature Driven Development (FDD) these are known as features and are similar to other approaches that incorporate an understanding of how the user makes use of the system such as by user stories.

User stories tend to have more clarity if developed in conjunction with the client and time is spent on considering how they will be tested. The user stories are stored in a product backlog and the Product Owner or representative from the client organisation determines the value of each of these and prioritises them. The development team then determines which are done within the next iteration. This is achieved by an initial planning meeting at the start of the iteration often lasting only 2 hours in which the stories are estimated by the development team as to how long these will take. The team also takes into account the priority within the product backlog as to which stories are to be developed for the next iteration, and reviews this when the iteration is completed.

Stand-up Meeting

At the start of each day there is a stand-up meeting. The idea is to keep the meeting short to a maximum of 15 minutes and to encourage comments to be kept succinct. Here team members outline briefly what they did yesterday, what were the impediments to getting certain tasks done, and what they are going to achieve today. Tasks and who is doing them are summarised on the whiteboard and because these commitments are made to the group there tends to be motivation to achieve what individuals have outlined as their tasks. After the short meeting a technical problem discussed will often immediately be resolved by others in the group dependent on whether it is an architecture, programming, or resource issue. There is regular feedback. Typically there is a retrospective or review at the end of each iteration to outline what went well and what didn’t go as well, but there are also daily reviews and the stand-up meeting helps highlight problems early.

The key is a built-in system of reviews at every level.

With my research groups after their projects, I asked them, if they were allowed to repeat their projects how long would they take to achieve the same results? Most had been working nearly 6 months and agreed that to repeat their work and achieve the same results would take less than half the time. Much of this is due to the learning curve, working out how to solve a problem, deciding the valid metrics, developing effective testing procedures, designing the tests and introducing automated testing procedures wherever possible. This is the importance of speeding up the cycle time to get results quickly and learn from them. To develop code and deliver this to the client after six months without a review with the client is a recipe for disaster. They will invariably say that this is not quite what they had envisaged. The feedbacks are necessary both for team learning and also to ensure that the teams are delivering the right product for the customer and ensuring that what they deliver is of the highest value and quality Collins (2013).

It is important for research groups to consider the value of the project management approaches and consider these as assisting rather than being an overhead. Techniques in testing clarify the goals and if testing is automated should accelerate the process. Both in research and development a more facilitative approach to project management is required. Within the Scrum method this is supported by role of the ScrumMaster whose function is to ensure that the processes determined by the group are followed.

Estimation

Within traditional approaches managers estimate and try to establish predictable plans and any deviation from these is seen as a problem with the development team. This approach often combined with a waterfall sequence of requirements for gathering, design, development, and testing is often a failure. The long list of requirements that may have taken months to gather is often out of date before the design is started. This is why it is so important to build something for the client to see at regular intervals to check that what is being built meets requirements.

Mike Cohn (2004) humorously points out in his book on user stories, using an analogy based on shopping, that seemingly trivial tasks often take several hours to complete. This is a way of introducing several important points about overoptimism in estimation, and not allowing enough time for technical development or thorough testing.

Of course, there are times when project managers may deliberately tell senior management what they want to hear, and agreeing to an unrealistically short schedule that the development team has no hope of achieving. With agile project management these aspects are substantially reduced. Firstly, the ‘death march’ scenario of no time and unrealistic planning from the project manager is avoided because the teams estimate their own work. The priorities determined by the client in effect decide what should be drawn from the product backlog and incorporated into the next iteration. This backlog can then be used as a clear measure to protect the team from unreasonable additional demands. If further tasks are added to the product backlog it is the priority of each that determines the urgency. As only a certain number of stories in terms of relative difficulty and duration in story points can be achieved in any iteration, there is an immediate indication of whether it may be feasible or even if it is a priority to add the new stories into the current iteration. The work is then delivered at a sustainable pace in a predictable way and the project schedule is fine-tuned as more process and project metrics become available.

One aspect of agile is using the ‘wisdom of crowds’, tapping into the fact that groups can estimate with better predicted outcomes and faster than individual team members. Earlier approaches have used Delphi techniques based on averages and giving higher ranking to central values. In recent years a popular technique that has been adopted by the agile community is ‘Planning Poker’. This allows the rapid estimation of user stories and will allow, based on these estimates, the team to plan a realistic set of user stories and constituent tasks for the current iteration. It is based on the concept that those doing the work are best placed to do the estimation. Also, as many of the benefits of estimation are quite quickly achieved, putting in more effort has decreasingly diminishing returns on accuracy.

Each of the development teams has a set of cards marked with a series of Fibonacci numbers. These are made up of the previous two numbers added, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, with the larger card not necessarily fitting in the sequence, say 100. There are other variants of this series that sum with 0 and a half, others based on multiples of 10, and others even with a question mark for the decisions that are difficult to initially make. The idea is that it is relatively easy to determine how long a task will take relative to another task, but this becomes more difficult as the size increases. As it becomes more difficult to differentiate between consecutive numbers as the task becomes bigger, so the widening gap makes it easier to estimate (e.g., it is easier to determine whether a task will take closer to 8 or 13 units than say 11 and 13 time units).

For each user story each member of the team estimates in story points the relative effort it is going take to develop and places their selected card with the value face down. As soon as everyone has done this they turn their cards over, to reveal their estimate at the same time. There may be consensus on the numbers say 3, 3, 3, and 5 in which case the card representing the generally agreed value is taken. However, if there is variation, a low and a high number say, those who selected these values outline their perspective and it may be that in light of this there are assumptions and technical issues that the others haven’t considered, and there is another round of voting. If there is consensus then the team can move on to the next story. Rounds without discussion as outlined by Amr Elssamadisy (2009) allow reflection and consensus, but may have the consequence of individuals being too influenced by the perceived leaders in the group.

If the team is working with user stories, then they need to estimate the relative size of these stories at the beginning of the iteration as a team. Mike Cohn (2004) points out this can be done in story points, which can be relative to the team’s own working practices and experience. However, the true measure of working becomes apparent from the team’s own measures of velocity, how many of their story points they are completing within a week or iteration. This measure can then be used as yesterday’s weather, to provide improved estimates of the rate of work, and better baseline the measures for completion of user stories and their constituent tasks to accomplish these (Cohn, 2006) (Figure A-1).

Figure A-1 Chart showing velocity or work achieved in story points during each iteration. This can help the team to determine the amount of story points they can realistically achieve in future iterations, and when the backlog is likely to be complete.

The team uses its own measures such as velocity and ‘burndown’ charts that show the remaining stories to be developed. As capabilities and features become increasingly clear and stable from management and the team acquires a sustainable development rate, the test data will support the figures to show when the project will be complete. The test data including percentage passing acceptance tests, the amount of code changes (churn), and the defect rates are going to be of particular importance in software development and will be used in conjunction to establishing realistic estimates for the overall completion of the project.

Technical Debt

Within the planning process of the iteration it is essential to consider the quality of the product and ensure attributes such as scalability and security. These may not always be outlined by the customer or the Product Owner, but to avoid technical debt and the code being difficult to maintain and extend these issues need to be addressed. It is important within the planning process that architectural issues are dealt with. One way in which to help achieve this is to consider not just the user functionality or user stories but also tasks that have to be achieved in order to keep the architecture aspects required. This can be achieved through a dependency mapping as outlined by Brown, et al (2010).

Defining the Architecture of the System

The architecture of a system describes its overall structure, components, interfaces, and behaviour. Definitions vary but often include the perspectives or views of the structure (Bass, Clements, and Kazman, 2003). One area that is emphasised by one instance of the generic Unified Process (UP) and Rational Unified Process (RUP) is the concept of requirements. In this case it is often user functionality via user cases and subsets of scenarios that shows what functionality a user or actor requires of the system.

Some agile methods such as Extreme Programming (XP) favour the use of understanding of the system in an exploratory way, via development of code, improving the design without affecting the behavior, i.e., refactoring. So for instance, developing a security check in a banking system would necessitate understanding the structure and coding this feature would verify and quickly establish an architecture, if there wasn’t a model already available.

Unless the architectural issues are addressed there will be inconsistencies in performance as the system is scaled. These defects will require ever more refactoring in order to avoid design problems. Therefore some consideration of the design is necessary to avoid later problems. This process of consideration of the planning of the architecture is termed architectural runway allowing for a smooth transition and rework and to avoid technical debt. Planning ahead, the architecture can be allocated on a planned process as advocated in agile architecture provisioning (Brown et al, 2010). Here architectural elements that are necessary for quality attributes (non-functional) such as security are allocated to the iteration backlog and provisioned within this period to carefully outline both functional and non-functional requirements, which are so important in determining scaling and performance factors. An alternative but similar approach would be to include design spikes at the Last Responsible Moment (LRM) to ensure the flexibility of the architecture. Where there is a choice of architecture this can then allow for a different approach to estimation of value. Instead of using a static cost-benefit analysis, which is normally based on static estimates and architecture, an investigation of alternative options and their relative future changes can be investigated and interpreted via real-options analysis (Bahsoon and Emmerich, 2004). This approach, which was originally developed in the financial markets, is increasingly used to determine the dynamically changing nature of viable options in areas such as provisioning of resources as in cloud provisioning within the IT sector (Collins, 2011). The nature of engineering is changing and increasingly ‘composing systems from open source, commercial, and proprietary components’ (Bosch, 2011), and in agile environments where the focus is on early exploration the ‘selection and trade-off decisions’ should be captured including the rationale that will help to understand why the product is better and why it is being built (CMMI, 2010). Pareto optimality and how this can be applied to balancing requirements as well as trade-off decisions for goals within project and programme management is a current area of research within the Faculty of Engineering Sciences at UCL.

Sharing knowledge and reflection

Research teams are well known for their synergy. Jeff Sutherland (2005) outlines this enthusiasm in agile projects and Dean Leffingwell (2007) outlines these concepts including how teams can create new points of view and resolve problems through dialogue. Within workshops, particularly in scientific research and innovation, it is useful to allow dialogue, not having to defend your idea, and allow further time to explore possibilities. This is refreshing, as often the stress is on discussions to resolve issues within a specified time period, i.e., time-boxing. Leffingwell also points out that in the spirit of Scrum, amongst its many attributes including commitment and autonomy, ‘leaders provide creative chaos’. This is precisely the concept that Sir Paul Nurse, during the BBC David Dimbleby lecture in 2012, was conveying when he was outlining how to create a collaborative environment for researchers to excel at the future Crick Institute.

For each project the degree of understanding of goals, emergent design needs to be considered and appropriate patterns need to be in place. Agile development and research both need process and governance frameworks.

Earned Value

With traditional project management progress is based on tracking the intermediate tasks, such as production of the requirements document and the design artefacts, which can be achieved without a demonstrable or working product. Allowing measures to be unrelated to working products can give a false sense of progress.

With agile the focus is on whether the software works, whether it is what the client intended, and whether it is of value. This is done via continual feedback via releases to demonstrate and allow feedback to improve the product and value.

To track progress towards goals in technology and IT projects where there is emergent design, this needs to be achieved at a higher level of abstraction. In research projects a clear idea of initial goals or exploration of concepts still needs careful planning; otherwise it will be unlikely that funding will be granted. In projects in technology and IT when there is emergent design this needs to be done at a higher level of abstraction. In large research projects a clear idea of initial goals or exploration of concepts still needs careful planning, otherwise it will be unlikely that funding will be granted.

There may be an exploratory phase equivalent to a feasibility study in which one or two workshops are planned to outline strategy or develop architecture to develop the technology. This initial phase will have clear goals and should have clear rationale for those invited. As this is bounded by time and consultants and facilitator costs the budget can be easily ascertained. This is likely if parties agree to an exploratory design phase, then a development phase.

During the initial phase in order to define the scope or boundaries of the research or development it will cover the goals that will in many instances then be broken down further to capabilities according to the type of innovation or development project.

Capabilities, a term often used in military projects, determine what is required without determining how this will be achieved. If this is a software development project these may be subdivided into features and stories. Sometimes the term epic in agile development is often used for a larger aggregation of features.

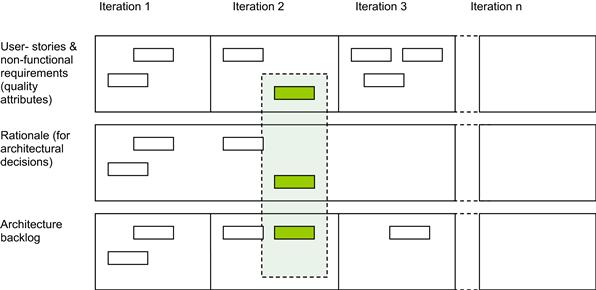

Figure A-2 Architectural elements in iteration planning Collins [2011] based on Brown et al [2010].

User stories represent what the client or Product Owner requires. These requirements are often written as a short outline on a card and then decomposed further to tasks. The Product Owner discusses with the team the prioritisation and order of development with regard to development issues including software architecture.

The use of Earned Value Management (EVM) is well developed in certain sectors of project management including the construction industry and is being increasingly mandated in defence projects in the UK. This can be applied to agile and software development. The essence of agile development is this shared collaborative communication between client and development team, ensuring value for the client and a motivated development team. Although management may be used to using earned value measures this needs to be developed for the agile process so that the development team doesn’t see this as an overhead and both groups can work collaboratively together. One criticism, however, of EVM is that this does not give an indication of the quality. One benefit of adapting this approach in conjunction with agile project management is that processes that improve quality, such as refactoring, are often incorporated into agile development practices.

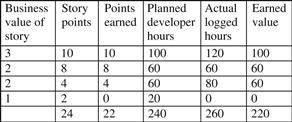

If EVM is required by senior management or through the governance process of the project, one approach is to create a reporting on two levels; one for the capability tracking and one based on stories as shown in Figure A-3, which can be generated with minimal overhead as part of the planning process.

Figure A-3 Earned value derived from stories completed at the end of an iteration. Story points are an estimate of the relative time that the development team thinks the work will take to complete.

In agile development there is continual prioritisation at the iteration level, which is designed to be the same duration. Earned value can be applied to these user stories, but there is a subtle difference in application. The reconciliation seems difficult as the user stories are continually under prioritisation according to the client as to what they consider the most valuable user story. These stories are stored on a backlog for selection during each iteration and the team estimates how large they are in terms of story points.

The stories according to prioritisation are selected for the iteration by the client on their perceived value. If the table is prefaced with the functional value or business value, the order of priority can be much clearer, although the highest priority should be at the top of the backlog and the development process then pulls the next set of stories and set of tasks.

As can be seen from the figure the earned value can be derived from the amount of completed work. For the first story, with the highest priority on the list and business value, the story was completed and therefore earned all the points.

Although the story took slightly longer than expected (i.e., 120 hours) the story was complete and therefore earned the full earned value of 100. Where the story was not complete it was allocated zero. From these figures schedule performance index (SPI) and cost performance index (CPI) can be ascertained to give an indication of progress (Collins, 2006).

Some have argued that velocity is more important. This is not the same as earned value. The velocity is the rate at which a team works and is a useful internal measure as are burndown charts, which show the remaining work and can act as a motivator for the team.

However, while it can be seen that earned value is valid within an iteration there are different interpretations of how this could work at higher levels of abstraction and the value to project management at a project level. Craig Larman (2004) suggests the use of estimates in terms of budgets. This is most easily achieved in terms of hours of work. He also outlines the concept of re-calculating the planned work for each iteration and as more information arises then the baseline is updated. For tasks to earn value it is prudent to only consider these when fully completed. However assessing this needs careful consideration as the development of each story is usually considered finished when all tests including integration and acceptance tests are completed.

It can be seen that using a simple spreadsheet as a by-product of the team’s estimates an EV system can be used as an indicator of progress in terms of business value.

Summary

In agile development it is often about trends emerging rather than making guesses about the future. Walker Royce has written about the indicators for converging on the solution and the indicators for value and progress (Royce, 2011). The way to gain credibility is through working with the client on a joint understanding of a problem, how to measure progress, and when to converge on the solution. This creates the real value, not only to the business, but to the self-worth of the team.

Agile project management is about achieving value collaboratively for the project and client team and the organisations concerned. This is not just about the bottom line but achieving something at work, feeling valued, and sharing knowledge with colleagues to achieve that next breakthrough. This is the true value of agile for individuals, the team, and the organisation.

At UCL at the front of projects are different types of workshops, examples of agile patterns that bring the right mix of researchers and project managers and support staff to solve problems. These vary from the Town Hall meetings where the challenge and opportunity is outlined to more detailed workshops allowing discussions and dialogue. The agile project management and development approaches favour the timeboxed approach to discussions, and estimation and often adding more time does not necessarily give a better outcome. It is these workshops which are often the driver for new innovations and approaches to development. The use of a trained facilitator is often vital with large programmes. It is important that staff with different technical approaches can outline their view. It may be that the idea is rejected in favour of an alternative idea discussed at the meeting. The key is fair process and that the team are deciding the direction. This is the essence of agile allowing the client to work with the development team collaboratively to decide capabilities they which to develop and prioritizing the functionality and user stories, or in the case of research the investigations. (Collins, Graham, UCL Research and Consulting projects (2003–2013), 2013)

It is self-evident that if one member of a team suggests a technical solution, another may disagree and point out an alternative and why in certain circumstances it is a better resolution.

Developing real-time modelling agile approaches with colleagues had a significant impact on communication and indirectly in one project resolving political issues by the clear focus on the technical problem rather than individuals. During a consulting assignment my colleagues in a small consulting group were asked to outline our object and business modelling approach. We had been asked for a solution and found on arrival at the client site already strained working relationships with a development project that had been ongoing for over a year. It was agreed to use our agile modelling approach to clarify the goals of the project and be clear on the direction. It was clear things were not going well, the project manager complained that he didn’t know what kind of project he was working on, as it wasn’t properly defined by the programme director. He didn’t know whether it was a business transformation project or a business improvement project. The client really wanted the project management problems to be resolved and not upset the director of the consulting firm under contract. It was a mess and an expensive mess with technical teams having worked for a considerable time. Without a real-time modelling solution and experience in forming a unified team this impasse would not have been resolved.

Getting buy-in wasn’t just a problem of clarifying the goals but getting support by understanding each of the stakeholder’s goals, communicating the direction over a short iteration with a clear product and defined time and engaging all stakeholders already working on the project.

The leader must be seen by others not to be gaining personally. In the case of the programme that had to be put back on track it was imperative to listen to the other parties and support each of their objectives so that the programme could move forward. Self-interest other than wishing for a successful outcome was not in the cards. Likewise the leaders in agile project management must lead by trusting their team and allow their team to deliver the project in a self-determined way. Self-organising teams and allowing them to report on progress are areas that the leader must embrace in agile project management. Much of what has been written on agile has been on what the teams do and how they track their progress. The burndown chart, keeping progress visible, and keeping tasks visible on the wall are for the team and the team leader. Keeping key tasks and communications visible, this is the ‘whitebox’ of progress reporting. It is the leader in agile project management who needs to understand this iterative process and be a resource provider, to remove all impediments to the team, who must trust his or her team to deliver in the technical approach they consider best. It is this beyond anything that defines the change to a leadership culture in agile.

The challenge in agile project management is not prescriptive plans and practices to follow but to populate the project planning process with appropriate patterns that are effective and add real value. For the time being the challenge must be to balance the planning so that you can achieve the flexibility to deliver increasingly complex projects and rapidly add new developments to enterprises and research establishments.

Bibliography

1. Bahsoon Rami, Emmerich Wolfgang. Evaluating Architectural Stability with Real Options Theory. Proceedings of the 20th IEEE International Conference on Software Maintenance (ICSM’04) 2004.

2. Bass Len, Clements Paul, Kazman Rick. Software Architecture in Practice Second Edition. SEI series in software engineering, Addison-Wesley 2003.

3. Bosch Jan. Keynote abstract Saturn Conference San Francisco. SEI May 2011; 16–20.

4. Brown Nanette, Nord Robert, Ozkaya Ipek. Enabling Agility Through Architecture CrossTalk. Nov/Dec 2010.

5. CMMI® for Development. Version 1.3 CMMI-DEV. V1.3, SEI November 2010.

6. Cockburn Alistair. Agile Software Development. Addison-Wesley 2002.

7. Cohn Mike. User Stories Applied. Addison-Wesley 2004.

8. Cohn Mike, Agile Estimating and Planning, Addison-Wesley. 2006.

9. Collins Graham. Experience in Developing Metrics for Agile Projects Compatible with CMMI Best Practice. SEI SEPG Conference Amsterdam June 2006; 12–15.

10. Collins Graham. Post-graduate course GZ07, academic year 2010-11. Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, UCL 2011a.

11. Collins Graham. Developing Agile Software Architecture using Real-Option Analysis and Value Engineering. SEI SEPG Conference Dublin June 2011; 2011b.

12. Collins Graham. Experience as lead consultant on commercial consulting project 1999-2000 included in GZ07 post-graduate teaching for GZ07 course. Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, UCL 2013.

13. Elssamadisy Amr. Agile Adoption Patterns: A Roadmap to Organisational Success. Addison-Wesley 2009.

14. Highsmith Jim. Agile Software Development Ecosystems. Addison-Wesley 2002.

15. Highsmith Jim. Agile Project Management. second edition Addison-Wesley 2010.

16. Larman Craig, Development Agile & Iterative. A Manager’s Guide. Addison-Wesley 2004.

17. Leffingwell Dean. Scaling Software Agility: Best Practices for Large Enterprises. Addison-Wesley 2007; (chapter 21 with Ken Schwaber).

18. Royce Walker. Measuring Agility and architectural Integrity. Int J Software Informatics. 2011;vol. 5(3):415–433.

19. Rule P. Grant, ‘What do we mean by ‘Lean’? Guest lecture for Professional Practice series, Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, UCL, 3rd February 2011.

20. Schwaber Ken. Agile Project Management, Microsoft. 2004.

21. Shalloway Alan, Beaver Guy, Trott James R. Lean-Agile Software Development: Achieveing Enterprise Agility. Addison-Wesley 2010.

22. Sutherland, Jeff, Future of Scrum: Support for Parallel Pipelining of Sprints in Complex Projects, Denver, CO: Agile 2005 Conference.