Chapter 3

Creating Strategic Alignment

Great strategies make great organizations. But only when they are implemented! A great strategy can focus everyone's attention on the collective purpose, the tactics required, and each individual's role in the process. Great strategies differentiate great organizations from their competition and highlight the unique value that they can create. Finally, great strategies are also built on the complementary capabilities of the organization and its people that no one else can imitate.1

But where do these great strategies come from? Examples like Steve Jobs's legendary control over every detail of a new product launch at Apple make it easy to claim that great strategies come from great leaders. But announcing a global launch should not be confused with delivering a global launch. Apple has mastered both. With each new product announcement, dates are set for the global launch. The product is manufactured and shipped to the stores, arriving the morning of the launch date. Employees are briefed shortly before the product goes on sale, and the crowds gather to see, touch, and buy their new product. The Legend grows.

At Mars, executives still tell the story of a two-day management meeting a few years ago. Day One was in Prague, and Day Two was in Budapest. After lunch on Day One, one of the Mars brothers interrupted the agenda and explained that the team needed to get on the bus because they were going to drive to Budapest. Raised eyebrows gave way to wide-eyed stares as the bus stopped at every store along the way to check on the product placement and shelf space given to Snickers, Mars bars, and M&M's. Connecting the big-picture strategy to the action on the ground takes a lot of discipline.

Ram Charan tells the story of DuPont's reaction to the financial crisis in October 2008.2 Sparked by a conversation with a Japanese customer, CEO Chad Holliday and his top team quickly formulated a strategy to conserve cash, so that they could survive in an environment in which capital and credit had disappeared overnight. The more impressive part of the story is that it took only ten days for every employee in the company to have a face-to-face meeting with a manager to identify three things that they could do to conserve cash and reduce costs. It took DuPont only six weeks to create the strategic alignment required to implement their plan to conserve cash.

Culture Eats Strategy for Lunch!

A successful business strategy always involves mobilizing people in pursuit of an organizational objective. Organizations must build a strong connection between the positioning of the firm and its products in the marketplace, the systems and structures needed to coordinate the required resources, and the mindset of the individuals who will deliver on the promise. Without careful attention to aligning people, the strategy is just a plan. What happens when a new strategy clashes with an old culture? “Culture eats strategy for lunch!”

This aphorism has been repeated so often that it is hard to determine who said it first. But it always reminds us that implementing a business strategy is very different from formulating a business strategy.3 Formulation can occur primarily at the top of organizations, but implementation can work only when alignment is achieved across levels, geographies, functions, product lines, and supply chains. After all, managing culture is about managing the balance between external adaptation and internal integration.

It Takes Time to Implement a New Strategy

Rolling out a new strategy takes a lot of time and effort. Consider this example from DeutscheTech, one of Germany's leading technology companies.4 DeutscheTech has several global business units that serve both consumer and industrial applications. Overall, these businesses generate over $20 billion in annual revenues and employ over fifty thousand workers in over 125 countries.

Culture is important to DeutscheTech, and it goes deep into the roots of a family firm that was founded back in the mid-nineteenth century. At the time that we were working with them, they described one of their core values as preserving that tradition of a family company. The family still has a strong presence in the company, even though their stock has been publicly traded for years. DeutscheTech also recognizes the strength of the bond between the company and its customers and knows the importance of long-term commitment.

Our example comes from DeutscheTech's adhesives business. The company is the global market leader in many of the types of adhesives, sealants, and surface treatments used in manufacturing. Their products help to make cars, appliances, and other manufactured goods quieter, safer, stronger, more comfortable, and more durable. Until 2003, their industrial adhesives and surface treatment technologies had been run as two separate business units. They had separate sales targets, sales forces, management hierarchies, and brands. They used different technologies, and the products were produced in different plants.

But the customers were often the same! Two or three of their salespeople might even be calling on the same client at the same time, competing for their attention, and positioning DeutscheTech as if it were two small suppliers rather than one large one. In addition, the complementarities between the technologies DeutscheTech uses to prepare metal surfaces for bonding and the adhesives that they use to stick them together were more difficult to realize because they were in two separate business units. So DeutscheTech made the decision to combine these two business units into one.

We tracked DeutscheTech's culture over several years while this strategy was being implemented. Tracking the evolution of their culture over this period of time helped to give us some good insights into the dynamics of the integration process in these two business units. We surveyed all of the levels of management around the world at DeutscheTech for several years using our Organizational Culture Survey. The results presented here describe the perspective of the four levels of management, L1 through L4, in an organization of over four thousand people.

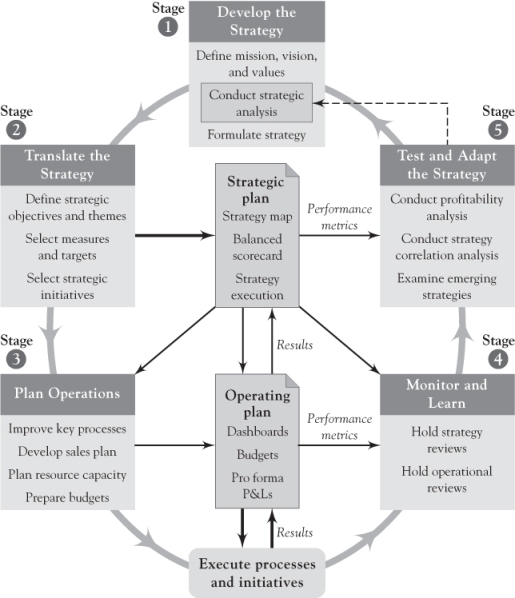

The results presented in Figure 3.1 focus on just one of the twelve indexes, the Vision index. The results show the perceptions of the vision for the business across the four levels of the management hierarchy in the new business unit that combined the adhesives and surface treatments businesses into one organization. There are five items that make up the Vision index as follows:

Figure 3.1 The Vision Index

The Vision index is the mean score for these five items, which were answered on a five-point Likert scale, with responses that ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The data in Figure 3.1 are presented as percentile scores, which reflect the percentage of the companies in our benchmark database who scored lower than this target sample.

These results help tell the story of how the leadership team in the adhesives business managed the strategy implementation process. When the management board saw the 2003 results, they realized that there was still a lot of work to do. The plan to integrate the two businesses had been announced throughout the organization, and the structural changes had been made at the top of the business unit. But it was apparent from the results that the overall vision for the business unit still wasn't very clear to the rest of the organization. The business was still production driven, and the products were still produced in different plants. The old mindset of two separate product organizations took time to change. Few of the salespeople could convincingly sell the whole product range, and they needed more cooperation among the different parts of the business to actually deliver for their customers.

As Figure 3.1 shows, the vision score in 2003 was below the 70th percentile for all of the management levels. But the scores were slightly higher at the top two levels, L1 and L2, and somewhat lower for the bottom two levels. Interestingly, the scores were lower for the third level of management than they were for the fourth level, who were the frontline supervisors. We have found that this can be a common situation during a strategic change, as the organization struggles to achieve alignment. The muddle is in the middle. Middle managers have to make the connection between the vision of the top executives and the realities of the marketplace. But on the front line, things haven't changed very much, and some people may still be playing “wait and see,” questioning whether the change is really going to happen. The daily reality of the marketplace continues to have a stronger impact than the new strategy and remains the main influence on the mindset of those on the front line.

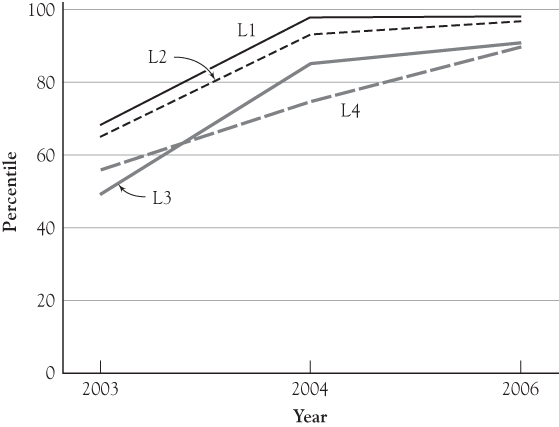

Figure 3.2 shows the responses across management levels over the same period for one specific item: “There is a long-term purpose and direction.” This item is a part of the Strategic Direction and Intent index, which is also part of the Mission trait. These results show an even more dramatic pattern. In 2003, all levels of management were average or below, with L1 and L2 scoring right around the 50th percentile and the two bottom levels scoring 20 points lower. It is normal to see a difference of 5 to 10 percentile points as you move across the levels of an organization, but differences of 30, 40, or even 50 points are usually a strong indication that there is more work to do to achieve alignment. Looking at these survey results across levels helped DeutscheTech to focus on their alignment, but it also forced them to see which parts of the organization needed the most help and attention and where they needed to direct their efforts in order to complete the integration process.

Figure 3.2 “There Is a Long-Term Purpose and Direction”

The leadership team in the adhesives business reacted to this situation by focusing more of their attention on the organization. They did more cross-training for their salespeople to ensure that they could all sell the entire product line. The technical groups cooperated more freely to offer better technical service and support to customers. These changes had a solid impact over the next year, as they showed a significant improvement both in overall vision and in long-term purpose and direction. The third-level managers, in particular, made a big improvement in Vision between 2003 and 2004, as they started to come into alignment with the leadership team in their business unit. But the alignment gap on the long-term purpose and direction item grew wider. At the top, the executives saw the purpose clearly, but the frontline leaders didn't notice that much difference.

Driving this strategic change deep into the organization took still more time. Not until 2006 do we clearly see that all levels of the organization are on board and in alignment. Moving to this stage took an entirely different approach, one that involved two important dimensions: visibility and dialogue. To build alignment, the leadership team took to the road to build their global presence. They explained the new organization, visited customers together with local teams, and most important, spent endless hours in dialogue, until they were sure that everyone in the organization understood what the strategic changes meant for their role. That's what it took to finally achieve alignment between their strategy and their culture.

Successful Culture Change Impacts Everyone in the Organization

Our second example of the important role that culture plays in the implementation of strategy comes from the financial services sector. Swiss Re is the world's second-largest reinsurance company, headquartered in Zurich, Switzerland. They were formed in 1863 to reinsure the risks from fires and floods that were being taken by the primary insurers in Switzerland's growing insurance industry. Swiss Re entered the American market in the late nineteenth century and soon paid out most of its capital to cover claims associated with the San Francisco earthquake in 1906. Today they operate in three business areas—property and casualty, life and health, and financial services—reinsuring large risks for primary insurers. Swiss Re's ten thousand employees in twenty-six countries generate revenues of around $30 billion.

Throughout most of the 1990s, Swiss Re competed in a “soft” market with low prices and readily available capital. Insurers had to pursue a top-line growth strategy, even if profitability was lagging. A strong stock market meant that the reinvestment of premium revenues could generate a strong overall return even if the initial investment wasn't very profitable. But by 2000, the business cycle had shifted to a “hard” market, with limited capital, rising prices, and a weak stock market.

The Americas Division was in trouble. Swiss national Andreas Beerli came over from Zurich to replace local management as the new division CEO. He faced a challenging situation: The business was losing money, but the current management team's combination of big-picture vision and decentralized style made it difficult for the organization to react to the crisis. The current leaders were bright, charismatic, and well liked, but they had not built a reputation for establishing a clear direction and getting things done.6

Change happened quickly. Andreas rebuilt the management team with new members who were relatively young and very experienced and had a reputation for success. Almost all came from within Swiss Re, but only a few had a prior working relationship with Andreas. In most cases, a few days of working closely together during the first few months of Andreas's tenure as CEO formed the basis for his decision. One observer commented, “In a short period of time, Andreas started making decisions about who he would trust. He is a good judge of character and can make decisions very quickly.” In twelve to eighteen months he had an entirely new leadership team.

The first change may have been the most important one: Andreas installed the best espresso machine in the building next to his office to encourage everyone to come by and talk. He moved the management board members' offices close together, so that they talked throughout the day, and he created an informal team atmosphere. Slowly a common understanding of the problems and opportunities began to emerge.

The most dramatic transformation took place in the US Direct business, led by French-Canadian Patrick Mailloux. US Direct sold reinsurance products directly to primary insurers, without working through brokers. In one three-day meeting, the new management team designed the new strategy, systems, and behaviors required to move their focus from the top line to the bottom line. But it was their changes to the “operating model” that had the most far-reaching impact. Making a decision about a reinsurance contract typically requires the combination of three separate perspectives: the client representative, the actuary, and the underwriter. The client representative interacts most closely with the client, understands their needs, and usually initiates the proposal for a deal. The actuary assesses the risks and sets a price, and the underwriter writes the contract. During the years when top-line growth was the strategy, the client representative was clearly the top dog. Younger actuaries and underwriters learned to “never say no” to a client representative, who was always motivated to close the deal.

This new operating model created a more equal balance of power in the team, so that any of the three could say “no.” This equal power helped ensure that new business contributed to bottom-line performance as well as top-line growth. Their choice of timing to implement this new way of working was bold—they chose to implement this during their annual renewal cycle. Each fall, reinsurance contracts are up for renewal for the following year. It is always a busy time and determines a lot of the company's success for the year. But this year, they were also learning a new model of how to do business. So at the end of each week during the renewal period, they also met together back at headquarters to track their progress and to ensure that their new priorities were in place to deliver on the bottom-line strategy.

US Direct CEO Patrick Mailloux reflected on the factors that were most important to the division's successful transformation:

We had the freedom to pick the team. We picked very good people, recognized their talents, moved them around, and let the cream rise to the top. We had to tell our message of bottom-line performance to people who had stopped caring. We had to convince them that we meant it and that you can't survive here if you don't care.

I love coming to work here because I get to work with the best. Andreas tells us where we need to go but not how to get there. If you are committed and you perform, then you have autonomy.

We are much more informal now, but much more direct. We have laughter, intellect, frustration. We think that simplicity is sexy. We created a totally different management board within two to three months. My conference table has name plaques for each of the members of the management board. It is a recognition of who is on the team and a reminder that we each need to earn the right to be at the next meeting. I don't expect them to be sitting there converting O2 to CO2.

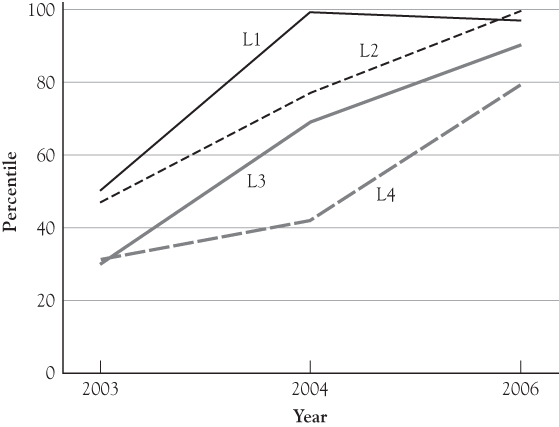

We tracked the Swiss Re culture over this period of time. The changes in the culture scores were dramatic, especially in the US Direct business. Figure 3.3 presents the changes in the overall culture profile, which is one of the most dramatic transformations that we have ever seen. In 2000, all of the scores were in the first quartile, reflecting a human organization that was not up to the task. Things changed slowly at first, but by 2002 they had created a high-performance culture that had transformed the business.

Figure 3.3 Comparing 2000 to 2002 Culture Survey Results: Swiss Re Americas Division, U.S. Direct Business

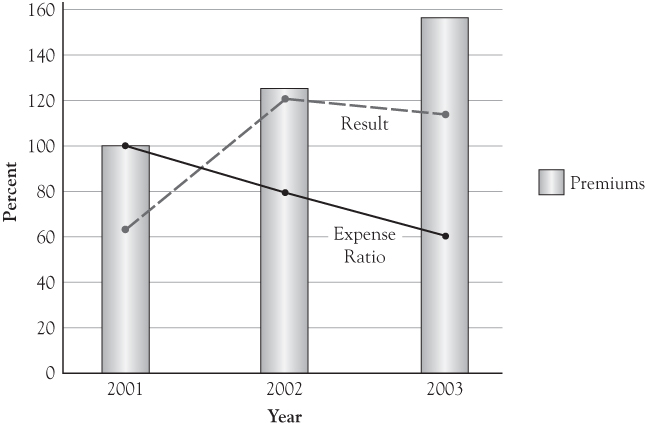

Business performance also changed dramatically over this period of time. Figure 3.4 presents the division's results for this time span, showing dramatic gains over the two years in several aspects of performance. Premium revenues were up by over 50 percent and were accompanied by strong gains in profit results and a marked decrease in expenses.

Figure 3.4 Swiss Re Americas Division Operating Performance 2001–2003

Source: Denison, 2004.

Lessons for Leaders

Sometimes there is a big disconnect between those who design a firm's strategy and those who are expected to carry it out. It is very tempting to sit at the top of a successful global corporation and contemplate your strategic options. But it is equally humbling to listen to the office chatter on the front line and realize how little impact your most profound strategic insights have on the day-to-day actions of the people who actually deliver the strategy to your customers. A disconnect makes it difficult to be agile, adaptive, or innovative, and makes it impossible to move fast enough to outflank your competition. But unfortunately, this kind of disconnect is all too common. Believe it or not, one organization that we worked with a few years ago even told us that their new strategy was being communicated only on a “need to know” basis! Creating a new strategy can be fun, but implementing it is hard work. Strategic alignment is the test of how well the organization has done at implementing its strategy.

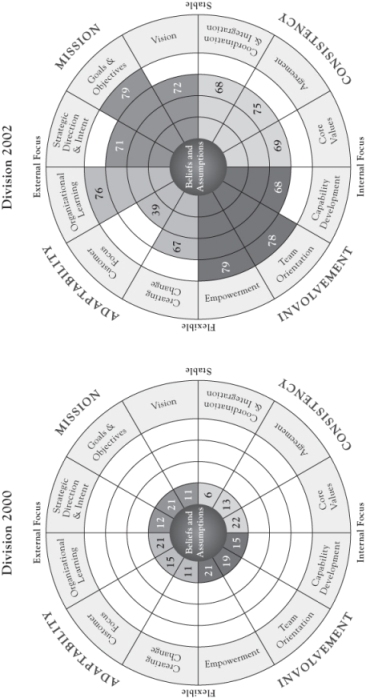

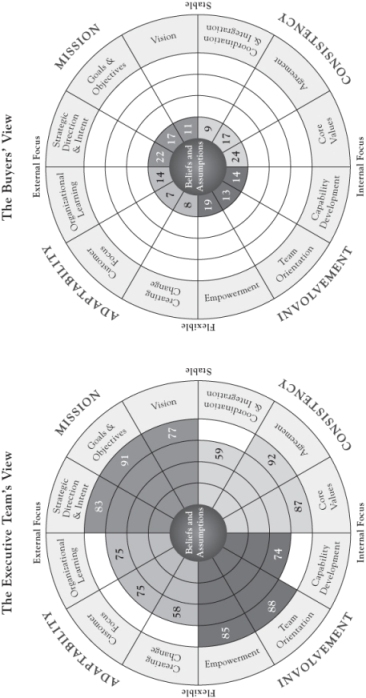

Several years ago we did a project with 4,500 people in the global purchasing department of a large manufacturing company. We surveyed them all. The results, presented in Figure 3.5, were quite shocking. At the top, the eight-person executive team saw the organization as being very effective. But the buyers, two levels down, saw something dramatically different: They saw an organization with a profile that they called the “donut of doom”!

Figure 3.5 Strategic Alignment in Global Purchasing

All of the scores were in the first quartile. In other words: no mission, no adaptability, no involvement, and no consistency. This extreme type of disconnect is very unusual, but the general dynamic is a familiar one. The cause is detachment from the day-to-day realities of the business, an insulated environment for the top leaders, and a genuine reluctance on their part to engage their people in open discussion.

Many lessons about strategic alignment can be drawn from the two case studies presented in this chapter. These lessons can be applied in any organization that wants to build a culture that creates a tight link between boardroom strategy and the action on the front line.

The Muddle Is in the Middle

Lack of alignment seldom occurs because top executives don't want to translate their strategy into action or because their people on the front line don't want to be effective in their roles. As we saw in the DeutscheTech case, the battleground is almost always in the middle. So the first step is always to understand where the disconnect actually occurs. Strategic alignment is built one conversation at a time. So it may start at the top, but creating alignment across the entire organization means that people at each level and location need to understand the strategy and their role in its implementation. The role of middle managers is to connect the vision of the top leaders to the reality of the marketplace.7

The chain of command is only as strong as its weakest link. To manage the implementation of a strategy, new or old, leaders need to find that weakest link and help them out. For all of the talk about “taking out levels of management” and “creating flatter, more responsive organizations,” it is amazing how little discussion there is about finding those in the middle who don't clearly understand their role in implementing the strategy, and taking the time to discuss and explain their role. As often as not, when leaders take the initiative to have this discussion—“managing by walking around,” as Tom Peters called it—they learn a lot about the logic of their organization and the gaps between the strategy, the marketplace, and the capabilities of the firm. In addition, the visibility and accessibility of the leaders builds trust and commitment when they show an interest in how the firm's strategy looks to their people across the levels of their organization.

Simplicity Is Sexy

I never thought that the reinsurance business could be sexy until I heard Swiss Re executive Patrick Mailloux say this. His message was clear: When the purpose is compelling, the goals are well understood, and the roles are well defined, it creates a focus that builds energy. The shared sense of purpose frees people up, even as they work intensely together as a team to get the job done. Simplicity requires that everyone “gets it.” The role of understanding cannot be overestimated. If people are still confused, the organization can't have a sense of simplicity. And that's not very sexy!

An organization's culture also plays an important role in resolving ambiguity and helping people sort out unfamiliar situations. Well-developed organizational cultures give a lot of redundant signals about the right and wrong ways to do things. All of the signs point in the same direction. The underlying assumptions and core logic of the firm provides a common point of reference that helps us find a simple response to a complex situation.

Deciding Who to Trust

One of the best lessons about leading change came from Andreas Beerli, CEO of Swiss Re's Americas Division in our case study. He didn't say it himself, but the point came through loud and clear from several executives on his new management team, as they talked about the way Andreas decided who he was going to trust with the key roles on his management team.

They noted that Andreas typically made up his mind about who he was going to trust for key roles in a relatively short period of time—usually within several months. He didn't just bring in former colleagues or pick from established relationships, but instead made his decisions based on intensive interactions over relatively short periods of time. One of his executives gave an example of spending two or three days working together with Andreas a couple of different times, over a period of six weeks while they were working on the new strategy. After that, Andreas asked him to join the management team.

The message from all of these stories was clear: You can't wait forever to decide whom you are going to trust. And the longer that you wait to choose, the more likely people are to conclude that you aren't going to trust anyone. Once this decision is made, the new team starts to come together. Andreas usually picked younger people who had a record of high achievement, great knowledge of the business, and a high level of energy. But trust came first. Trust allows you to move fast.8

A Successful Transformation Has an Impact on Everyone

Successful transformations require deep involvement. Another important lesson from the Swiss Re case emerges from when they redefined their “operating model.” To move from a top-line strategy to a bottom-line strategy, they needed to make decisions about a new business opportunity with a three-person team at the table: a client representative, an actuary, and an underwriter. This was a big departure from the days of the top-line strategy, when the client representatives held the most power. This power shift and new way of working together influenced thousands of decisions—and hundreds of people, as they learned a new way to work together to breathe life into the new strategy.

This case is also a great example of how important it is to find the pulse of the organization when you are trying to create a change. Swiss Re implemented this change in the middle of the busiest period of the year: the renewal season in the autumn, when all of their contracts were updated and renewed for the coming year. They certainly would have had more time to put the new operating model in place if they had waited until after the first of the year. But timing is everything. If the changes are not implemented when they really count, then the opportunity has been lost until the next cycle comes around. When you are trying to change an organization, you must understand the dynamics of your organization's business cycle. What timing gives you the greatest leverage with which to drive the change process? In the fashion business, for example, designers always create new styles two or three seasons ahead of the time when they will actually be sold. Trying to intervene when the new products are already on the way to the stores would be pointless. So it is very important to “find the pulse” and use that cycle to build momentum for the transformation.

Creating Strategic Alignment: Beyond DeutscheTech and Swiss Re

Strategic alignment is always achieved by creating a clear cycle that connects strategy formulation and strategy implementation. The strategies that are formulated need to reflect the business realities on the ground. This means that the experience of all levels of an organization is critically important to formulating a new strategy. When formulation is done only at the top, there is an increased likelihood that the organization will choose a strategy that it cannot really implement. The top, the middle, and the bottom all need to collaborate in order to bring together knowledge from both inside and outside the organization. In some firms and industries the best vantage point for understanding the competition is at the top, where the leaders can see the latest developments in the marketplace. But in other firms the best knowledge of the competition is on the front line, where the battle is fought every day. In other firms, the best understanding of the competition is in the design studio or the R&D labs, where relentless product improvements are constantly created. The alignment of all of these forces is what characterizes the most successful strategies.

When it comes to implementation, the link between the top, the middle, and the bottom becomes even more important. The implementation process is the only way to execute the strategy—and the only way to test the strategy. After all, you can't really judge the success of a new strategy until you have actually tried it. So up and down the line there are two goals that must be pursued in parallel: execution and learning. “Just do what I say” might sometimes be good advice for execution, but it is most often poor advice for learning.

The Cycle of Strategy Formulation and Implementation

One of the most useful ways to look at the cycle of strategy formulation and implementation is the one provided by balanced scorecard gurus Robert Kaplan and David Norton. An overview of their model is presented in Figure 3.6.9

Kaplan and Norton point out that the process usually starts at the top, with mission, vision, and values. Translating this plan into action requires a set of measures, targets, and strategic initiatives for all of the different parts of the organization. Next comes planning and implementing this at an operational level. But after this stage the focus turns to monitoring and learning and then to testing and adapting. This learning process is a key part of developing the strategy for the next cycle. Then the process starts all over again.10 Organizations that do this well can create “a performance-directed culture … one in which everyone is actively aligned with the organization's mission; transparency and accountability are the norm, new insights are acted on in unison, and conflicts are resolved positively and effectively.”11

Mobilizing Mindset

The link between the mindset of the people and the logic of the system that they create is always at the heart of the alignment process. The mindset and the system are two sides of the same coin. Sometimes we can change our mindset by immersing ourselves in a new system. But other times, “successful change only comes when we view the world with new eyes.”12 The survey process in each of these organizations helped them see that the mindset and systems that they had created in the past were no longer suited to their current challenges. That insight built a lot of energy and ambition and drove them to innovate together and to plan a future that would be different from the past.

Notes

1 Porter, Michael. “What Is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review, November-December 1996, 61–78.

2 Charan, Ram. Leadership in the Era of Economic Uncertainty (see ch. 1, n. 32).

3 Kaplan, Robert S., and Norton, David P. “Mastering the Management System.” Harvard Business Review, January 2008, 63–77.

4 At the company's request, we have adopted a pseudonym for this firm.

5 Although statement 3 is negatively worded, its response scores are reversed(R), so a higher percentile score indicates a better condition for all five statements.

6 Denison, Daniel R. “Swiss Re Americas Division.” Lausanne, Switzerland: IMD Business School, IMD 4–0281, 2004.

7 Nonaka, Ikujiro. “Toward Middle-Up-Down Management: Accelerating Information Creation.” Sloan Management Review 29, no. 3 (1988): 9–18.

8 Covey, Stephen M. R. The Speed of Trust: The One Thing That Changes Everything. New York: Free Press, 2006.

9 Kaplan and Norton, “Mastering the Management System.”

10 Two useful articles that give an overview of the alignment process are Collins, Jim, “Aligning with Vision and Values.” Leadership Excellence, 23, no. 4 (2006): 6; Sull, Donald, “Closing the Gap Between Strategy and Execution.” MIT Sloan Management Review 48, no. 4 (Summer 2007): 30–38.

11 Dresner, Howard. “Building a Performance-Directed Culture.” Balanced Scorecard Report (Harvard Business Publishing), January-February 2010, 3–8.

12 Carr, Patricia. “Riding the Tiger of Culture Change.” T+D, August 2004, 32–41.