Chapter 7

Building a Global Business from an Emerging Market

In the past decade, high-profile companies from emerging markets have surprised analysts by expanding dramatically in “mature” markets. They have expanded through organic growth and by acquiring companies in other emerging markets, but they have also expanded by acquiring established multinationals in developed markets. And the phenomenon is not linked to just one industry. The auto, computer, pharmaceutical, mining, and luxury goods industries have all seen companies from the emerging markets acquire companies in the developed markets. Examples include Lenovo's (China) purchase of IBM; AmBev's (Brazil) purchase of Interbrew (Belgium) to create InBev, which then bought Anheuser-Busch (USA); Mittal Steel's takeover of Arcelor to form ArcelorMittal; Lupin Pharmaceuticals's (India) acquisition of Hormosan Pharma (Germany); Yanzhou Coal Mining Company's (China) purchase of Felix Resources (Australia); and China Haidian Holdings's acquisition of the watchmaker Eterna (Switzerland). The list keeps growing.

The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) noticed this trend a few years ago and began publishing a list of “Global Challengers.”1 These organizations were the ones from the emerging economies that were the most successful at globalizing their businesses. The Global Challengers came primarily from the BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China)—such as China State Construction, CHINT Group, Embraer, Marcopolo, Bharti Airtel, Lupin Pharmaceuticals, and Gazprom—and are now competing directly with established multinationals for global leadership in their industries.2 But the number of companies from emerging markets that were expanding globally was growing so quickly that in 2011 BCG added a new category: Global Challenger Emeritus. This first group of Emeriti included Vale, the Brazilian mining company that is the focus of our discussion in this chapter. Vale was a Global Challenger in 2006, but now looks much more like an established multinational.

How do emerging market companies grow into Global Challengers? Research has shown that organizations in emerging markets pursue cross-border acquisitions to gain competencies such as technologies, assets, or brands. They typically do so by going through three stages: they start in their home countries, internationalize by expanding to similar markets nearby, and finally go global. During each stage they learn a set of lessons that can be applied to the next stage.3 An essential part of this learning process is the adaptation of the organization's culture to a global environment and a global role. To succeed, they must learn as they go. They may have all the systems and processes in place to execute strategy, but if they are not quick to learn and adapt their culture, then they are unlikely to succeed.

The first stage of the adaptation process is a focus on getting the organization's house in order in their home market. Organizations must adapt internally to create a strong and unified culture that is the foundation for growth. In the second stage, organizations test the waters by expanding in the markets and products that are most similar to their home markets, diversifying through joint ventures, strategic alliances, or acquisitions. Again, these developments allow organizations to adapt their structures, cultures, and business practices to an international set of demands. Finally, to create a truly global reach, organizations typically push forward, with both organic growth strategies and growth through acquisitions, to establish a sustainable global footprint. To successfully navigate these three stages, organizations must closely align their cultural adaptation with their strategic objectives.

In this chapter, we will follow the development of Vale through these three stages. In 2001 they were a state-owned iron ore company that was hierarchical but decentralized. How is it possible to have a hierarchical, top-down culture in a decentralized company? In Vale's case, the company was organized around individual mines. The head of each mining operation had a clear mandate from headquarters regarding the results they were supposed to achieve, but how those leaders went about achieving their results was up to them. And the mines were usually a long way from the headquarters in Rio de Janeiro.

In the second stage of their evolution, Vale's focus shifted to becoming an international organization. During this time the pendulum started to swing toward the centralization and professionalization of the organization. Their managers started to benefit from a bit more freedom and autonomy. In the third stage, Vale grew into a well-established, highly professionalized global player with a more adaptable and open culture. This moved the pendulum back again toward decentralization and empowerment, but now with a much higher level of professionalism. By 2011 Vale had achieved outstanding business results that were acknowledged by their promotion to the Global Challengers “Emeritus” category.

Becoming a Global Challenger

It was in 1942 when the Brazilian government took control of two mining companies and a railway and created Vale's predecessor, Companhia Vale do Rio Doce (CVRD). (For simplicity's sake we refer to the company as Vale throughout the chapter, although it was known as CVRD until it adopted Vale as the global brand in 2007.) Over time it flourished and grew, adding both shipping and port management to its mining and railway operations. Its modern era began in 1997 when the Brazilian government began to privatize the iron ore company. Vale was fully privatized in March 2001, and in July of that year Roger Agnelli was appointed CEO. (In keeping with the Vale culture, we refer to Mr. Agnelli throughout the chapter as Roger.) According to company documents, his vision was for Vale “to become a global mining-focused multi-business company and a major global competitor in logistics and energy-related business, with a market valuation of $25 billion in 2010.”

Getting the Brazilian Business in Order

When Roger took over as CEO, Vale was just starting to adjust to its status as a privately owned company. They still operated as a government-owned iron-ore company. During this period Vale described itself as “one of the world's largest producers and exporters of iron ore and pellets. We are the largest diversified mining company in the Americas by market capitalizations and one of the largest companies in Brazil.”4

To become an international iron ore company and then a global mining company, Vale had to change both their mindset and their structure while simultaneously expanding their international operations. The biggest mindset change required was for its leaders to view Vale as one company. This was easier said than done. In 2001, Vale's culture was quite fragmented, made up of a series of mines that in most cases were run like individual fiefdoms. Each of Vale's business groups was run independently, and they did not use the same back-office operations. This resulted in a great variety of idiosyncrasies in the way in which the organization's back-office operations—finance, purchasing, logistics, accounting, human resources (HR), and operations—were organized. In addition, the decision-making process was informal. The CFO commented that in those days many of the relationships with suppliers were based on nothing more than a handshake. This made it very difficult for new managers to understand what kind of commitments Vale had made and how some of these relationships could be more formally structured. This gave Vale the unusual corporate culture mentioned earlier—informal, yet hierarchical and decentralized.

One of Roger's key priorities in these early days was to create “one Vale.” This meant that the first step in the process was to move toward a more centralized model that would eliminate the individual fiefdoms that existed throughout the company. To do this, Vale started to standardize practices in human resources, finance, supply chain, accounting, and other processes. This included the introduction of standard ordering procedures, formalized contracting processes (rather than handshakes), consistent financial audits, regular performance appraisals, and much, much more. Getting the Brazilian business in order meant the introduction of professional standards in all functions and operations. These new standards helped diminish the power of the fiefdoms, as did the introduction of the same standard financial performance measures for all of the mining operations. This meant that the culture slowly shifted from local fiefdoms to a more professional mindset. At the same time, Roger refocused Vale's strategy on its mining, logistics, and energy businesses.

Although the professionalization of Vale was helped by the introduction of standardized processes, a professional mindset was more difficult to create. The legacy of having had a strong fiefdom culture in both the mines and headquarters meant that most people were passive—used to waiting to be told what to do and how to do it. There was also a culture of blame. Managers knew that when mistakes were made, someone had to pay the price rather than learning from the mistakes and trying to improve. For example, when a section of a primary rainforest was mistakenly logged, Vale fired the person responsible rather than trying to understand and correct the process that had led to the problem. So although professional processes and structures were introduced relatively easily, the mindset shift from passive to active and from blaming to learning took much longer.

Becoming an Internationally Diversified Company

By 2003, Vale had made a lot of progress in getting their house in order, At this point, they started to adjust their vision of the future and what it might be:

To be a Brazilian global business company ranking [among] the world's three leading diversified mining companies, and to achieve excellence in research, development, project implementation and business operations by 2010.5

As Vale expanded into other countries—such as Australia, China, Indonesia, and Canada—they typically used Brazilians rather than locals for the key leadership positions, such as senior geologist and country manager, because they feared losing control or hiring someone who did not “know the Vale way of doing things.” Sending out expatriates who were familiar with the informal, top-down, and centralized way of doing business was an important step in the process of combining professionalization and empowerment in their uniquely Brazilian way. Because they knew the “Vale way,” these Brazilian expats were allowed to operate more independently.

But even when the top management team and the Brazilian expats had a well-defined and well-understood strategy, they did not always communicate it well to the rest of the organization. Their involvement of the middle managers in running the local businesses still had a long way to go. Corporate HR helped by working with the businesses to define the capabilities that they needed—immediate, medium-term and long-term—to deliver on the company strategy. Succession planning was one key area in which they made a major improvement.

Many leaders also noted that changing HR's interaction with the business was a fundamental step for Vale to create one culture and mindset and become a global mining company. They also involved the lower levels of management by launching Vale's Corporate University, to provide technical, geological, and leadership training to all levels of management. This was essential in spreading the Vale culture and in driving Vale's transformation. The HR executive director noted:

The first challenge was to determine if we were going to do a turnaround (change in a short period or time) or a transformation (making gradual changes with the people and assets available). I believed we were doing a transformation. So, we had to develop a people strategy because we did not have enough capabilities for sustained growth. We did this at the same time that we were transforming the Brazilian iron ore company into a global, diversified company.

The company also continued to create “one Vale” by creating a shared service department, which consolidated all back-office functions into one central operation. This included procurement, warehouse and inventory management, recruitment, payroll, training, execution, benefits administration, accounts payable, accounts receivable, and tax collection. In creating this department, Vale not only looked for synergies throughout the company but also captured and built upon their experience integrating earlier acquisitions. The director of the Shared Services group described their mission:

The whole idea of implementing shared services was to create what we are calling a “plug and play” back office; that we can absorb or integrate a new company or even a project that is coming into operation into this Vale management model a lot faster than we did before.

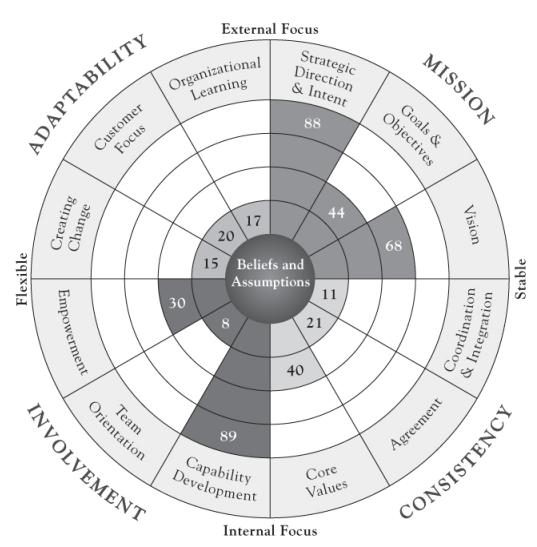

To assess the progress they had made, in 2006 Vale asked its top two hundred leaders to complete our Organizational Culture Survey. As the results in Figure 7.1 show, the company had done a great job in communicating the strategy and in developing its own people. However, the results show that the blame culture was still alive and well and that different business units did not work well together. In spite of taking many steps to internationalize, their scores on adaptability—creating change, customer focus, and organizational learning—were still very low. So although great progress had been made in terms of having one vision and strategy, there was still a silo mentality in the different local organizations.

Figure 7.1 2006 Culture Survey Results: Vale

Going Global

During this third stage, Vale became more serious about becoming a truly global, diversified mining company. They had to expand their product lines and their geographic reach. In August 2006, Vale made an all-cash offer for the Canadian nickel mining company Inco. This was the largest deal ever done in either Latin America or Canada, and it was bigger than the total of all of Vale's other acquisitions combined. The acquisition came as a surprise to both the industry and to Inco. As one Inco executive said, “Who were these people coming from Brazil? We had never heard of them.”6

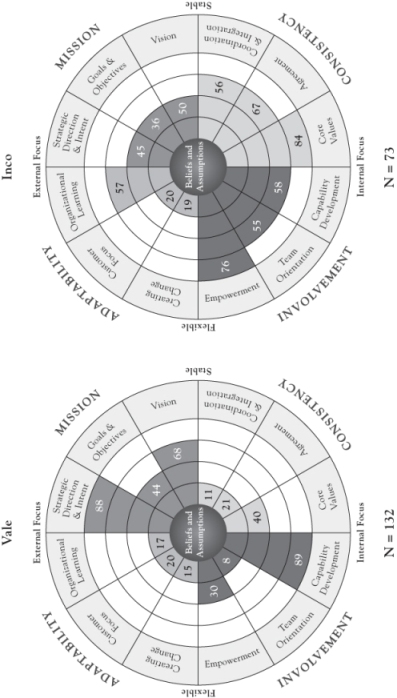

The cultural differences between Vale and Vale Inco were also apparent in the survey results (see Figure 7.2). Managers were not given much discretion in decision making, but the managers at Vale Inco in Canada were used to a decentralized organization, which gave them a much wider scope in which to achieve their goals. Their scores on empowerment, team orientation, and organizational learning were much higher than Vale's. However, Vale was much higher on strategic direction and intent, vision, and capability development.

Figure 7.2 Comparing 2006 Culture Survey Results: Vale (Overall) Versus Inco

Hooijberg and Lane, 2009.

The different national cultures also played an important part in the survey results. The managers in North America expected their leaders to explain why a process or system was being implemented and expected that they would be consulted about how the changes should be implemented. The Brazilian managers, coming from a more top-down culture, did not expect to be asked for so many explanations or consultations. As one leader described it, Inco's culture had always been one in which top management decided the general direction and then delegated the implementation to the middle managers, who were given the freedom and decision-making authority to achieve those goals. On the one hand, from the Inco perspective, Vale executives didn't always communicate the context for their decisions very clearly. For example, when they decided to create one global compensation system, Vale headquarters simply sent an e-mail instructing Inco to implement the new compensation plan, rather than going to Canada and explaining the logic behind the new plan. On the other hand, the Brazilians always thought that the Canadians were spending too much time questioning their decisions.

Communicating across cultures always has its challenges. One of the key lessons that the Canadians and the Brazilians learned while working together was about the way that they used the words “question” (pergunta) and “doubt” (dúvida). In Portuguese, the words are distinct, but the concepts are closely linked together. In Portuguese, you ask a pergunta because you have a dúvida. Dúvida does not imply a lack of trust or confidence in the same way that “doubt” does in English; it simply signals a gap in understanding, a challenge to be resolved, or an issue about which someone has a question.

So when Vale executives visited Inco, they expressed lots of dúvidas—issues about which they had questions. But they often used the English word “doubt” to describe the issues they were trying to understand. The Canadians often took this as a lack of confidence, or an absence of trust, rather than an expression of curiosity. That was not what the Brazilians intended, but it took everyone several months to realize the problems that this misunderstanding had created.

In 2007 Vale continued their global expansion by buying the Australian coal mining company AMCI Holdings. AMCI had been put together by private equity investors in the early 2000s with the goal of a quick sale. Because of this background, AMCI had minimal systems and processes; AMCI's managers found it relatively easy to implement Vale's “plug-and-play” shared services concept. The overall integration of AMCI into Vale had its challenges, but it was much smoother than the Vale Inco integration.

During this acquisition period Vale also decided to try to create more bottom-up participation. To achieve this goal, they created two executive programs to develop their senior leaders: in the United States MIT created a program for general management, and in Switzerland IMD developed a program for leadership training. These programs addressed multiple items that were identified by the Culture Survey. First, both programs were clearly focused on developing capability. Second, the programs directly addressed some of the challenges identified in areas such as empowerment, teamwork, organizational learning, creating change, agreement, and coordination.

The leadership program focused on such topics as organizational culture, change management, self-awareness, and working as a team. One of the key elements in the program was the use of a 360-degree feedback tool, based on the same model as the Culture Survey. In Vale, this was the first time that direct reports and peers, in addition to bosses, had provided feedback on the managers' leadership behaviors. This was a huge step in a traditionally top-down culture. The results of the Culture Survey itself were also openly discussed. Each program also included an executive director who held an open-ended discussion with the participants on the last day of the program.

Bottom-up participation was further encouraged in the Global Leadership Forums that Vale organized in 2007 and 2008, providing a chance for the top five hundred leaders to meet face-to-face and discuss the issues confronting the company. These forums provided top management with a way to deliver their views on Vale's future and an opportunity for the participants to air their opinions about the challenges they faced and how Vale's approach was working.

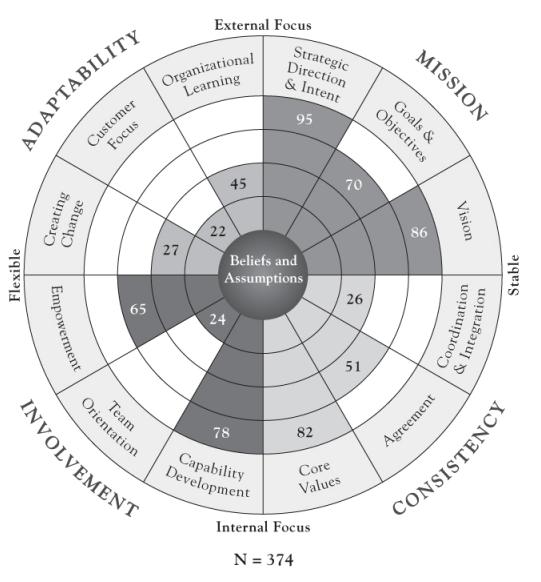

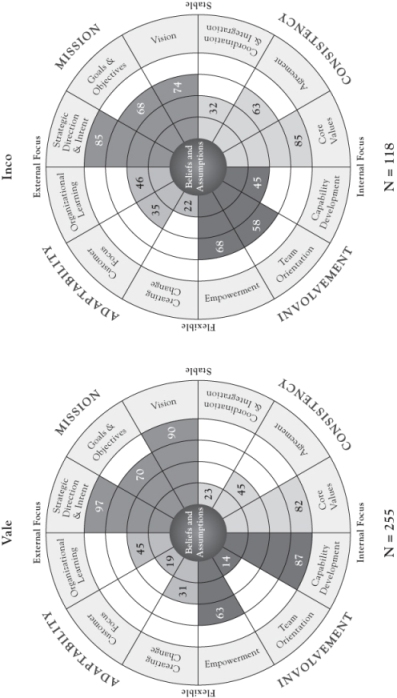

By 2009, Vale had become a diversified global mining company. Along with the changes in the business portfolio and the geography, the culture had also changed significantly. The results from the 2008 Culture Survey, shown in Figure 7.3, reveal that almost all areas saw significant improvements. The results were especially impressive in the areas of empowerment, core values, and vision. Another example of progress is that the culture profiles for Vale and Vale Inco, presented in Figure 7.4, now looked very similar, indicating that a relatively high level of integration had been achieved.

Figure 7.3 2008 Culture Survey Results: Vale

Figure 7.4 Comparing 2008 Culture Survey Results: Vale Versus Inco

These improvements did not just show up in the survey results. We also saw these changes at the Global Leadership Forums and in the leadership courses. Employees sensed the difference. They felt that their opinions were taken into consideration and their voices were heard. One long-term employee noted that Vale's top leaders had become much more engaged and communicated better with their people. Another executive noted that the board was also more open to discussion, and that their openness and willingness to discuss cascaded down to the rest of Vale.

After 2006, Vale also began to hire more locals as senior managers or senior geologists, instead of relying only on Brazilian expatriates. The big advantage of this was that Vale could then learn from the local employees about their country's customs, traditions, and way of working. Many people remarked that the blame culture had changed: Vale made an effort to learn from mistakes rather than just looking for a scapegoat. However, they also worried that the changed financial situation stemming from the 2008 financial crisis would bring back the blame culture.

The integration of Inco and AMCI Holdings also marked Vale's growing ability to manage using a global mindset. For example, when making decisions management would consider the impact on all its regions, not just the impact in Brazil. Vale also began attracting managers from the outside who embraced change; it was becoming a company with an increasingly younger mentality. The newer managers—in 2008, 70 percent of Vale managers had fewer than five years of experience with the company—were not as steeped in the old culture and were more open to change. Overall, employees were more entrepreneurial and willing to try out new things.

Lessons for Leaders

In less than a decade, Vale transformed itself from a decentralized, government-owned organization with a top-down culture to one that was professional, centralized, empowered, and global. Its operating revenue grew from $3.1 billion in 2002 to $37.4 billion in 2008. Growth like this required Vale to adapt both its strategy and its culture. Several clear lessons stand out from this successful transformation.

First, Put Your Own House in Order

The 2011 BCG report noted that the emerging market companies that had become global players started by being “financially fit and able to take advantage of opportunities to buy attractive assets and compete against more established competitors that are still in recovery mode.” As examples, they highlight not only Vale, but also such companies as Lenovo, Tata, Bharti Airtel, El Sewedy Electric, Yanzhou Coal Mining Company, and Wilmar International. All of these businesses first built up their strength nationally before aggressively expanding internationally. Not only were these companies financially fit before expanding internationally, but they also had acquired significant experience in integrating acquisitions in their local markets. This highlights both the professionalism of the companies as well as the clarity of their vision.

Many of the emerging market companies show similar patterns of geographic expansion. In its first one hundred years, up until 2000, Tata never acquired any companies outside of India's borders. Egypt's El Sewedy Electric was established in 1938 but didn't enter into its first joint venture until 2002 and didn't make its first acquisition until 2008.

The Balance Between Professionalism and Empowerment

Going global from an emerging market requires developing a culture of empowered professionals orchestrated by a centralized core. A lot of global expertise must be developed in the local markets to support successful decentralization, and a lot of local expertise must be developed in headquarters to support successful centralization. Organizations need to be both centralized and decentralized, according to what works best for thousands of processes and procedures. The right balance of professionalism and empowerment is hard to achieve—and harder to maintain.

As an example, at one point “professionalization” at Vale meant that the executive board became involved in the appointment of managers as many as four levels below the board. This standardization of procedures, KPIs, and appointment criteria allowed Vale to strongly influence the professionalization of its culture. The upgrade in professionalization also provided these companies with the trust in their leaders when they sent them abroad to run acquisitions, participate in partnerships, and build up greenfield sites. Centralizing the appointment of managers for a few years allowed the organization to then achieve greater decentralization of the operations as they developed more capability and trust on the ground.

Another interesting example of the importance of professionalism is Hindalco. In six years, Hindalco jumped from being India's largest producer of aluminum to being a major global player. They moved from supplying aluminum to others to acquiring the American company Novelis, a world leader in producing flat-rolled aluminum and aluminum products, for $6 billion in 2007. Another company Hindalco acquired along the way was Indal, an Indian manufacturer that not only developed aluminum products but also had developed the capacity to brand and distribute them.

But Indal's managers were worried that Hindalco's culture, which they characterized as a family business, would ruin their culture, which they viewed as professionally managed. Hindalco reassured them that it was buying talent, not just assets, and that they would always pick the best manager for the job. They backed up this claim by keeping Indal's senior management and giving the job of CFO of Hindalco after the merger to an Indal executive. Hindalco's integration consistently focused on using whichever business process works best.7

Building a Global Business from an Emerging Market: Beyond Vale

One of the most valuable lessons from Vale concerns the importance of vision. This theme is also strongly reflected in the experience of a number of the other Global Challengers. All of the examples we could find involved CEOs and other leaders with a remarkable sense of vision. At each stage, the vision was re-created to extend and energize these Global Challengers.

The importance of having a visionary, hard-driving CEO cannot be underestimated. Liu Chuanzhi, CEO of Lenovo during much of its history, began his journey soon after China took its first steps toward privatization. He had been employed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) in its Institute of Computing Technology as a scientist and had participated in the development of over twenty mainframe computers. However, he was unhappy about the decline in the Computer Institute's prospects in the face of budget cuts and priorities shifting away from research on mainframes. When he decided to set up a company, funded with RMB 200,000, he and three others had to convince their scientific colleagues to overcome their distaste for business and join them in the unknown. They did not really have a plan other than wanting to take part in technology development. In the early days of the company, Liu insisted on maintaining close ties with the CAS. In 1985, one faction in Lenovo wanted to break free of the Academy. But Liu insisted that there were enormous advantages in maintaining the ties to the people, the research, and the financial backing.8

Liu went on to steer the organization through the changing Chinese landscape. He took control from the start in 1984 when the CAS funded Lenovo. He tried to make sure that the government had no say in the management—Lenovo had the right to control their finances, make hiring and firing decisions, and make decisions about the company's operations.9 When the Chinese government refused to grant licenses to produce PCs on the mainland, Liu set up a factory in Hong Kong. When China entered into the WTO and Lenovo faced more international competition, he launched a series of mass-market PCs that were low-cost and high-quality.10 Wong Mai Min, CFO and senior vice president, believes that Liu's visionary and strategic leadership contributed to Lenovo's success.11

It was not always a smooth ride for Lenovo. After Liu handed over management of the merged firm to Western managers, there was a culture clash that hampered its ability to strike a balance between IBM's focus on big customers and the faster-growing segments of the PC market for small businesses and customers. Furthermore, the 2008 financial crisis hit sales, and Lenovo experienced a $97 million loss in the quarter ending December 2008. Liu returned to manage the company. He was worried that the former CEO's management style was too top-down and dominant—with the CEO making the decision and then working with individual leaders of the top management team to implement it. This was in contrast to the consensus-based style Liu developed over the years “in which the CEO develops and implements strategy as part of a tight-knit group of executives.”12

In the past, Westerners often thought of emerging economies primarily as a source of cheap production for the established economies. As this chapter demonstrates, however, it is clear that this view is way out of date. Global organizations need to recognize these as high-growth economies led by rapidly professionalizing companies with global aspirations.

Notes

1 Aguiar, Marcos, et al. “The New Global Challengers: How 100 Top Companies from Rapidly Developing Economies Are Changing the World.” Boston Consulting Group, May 2006.

2 Verma, Sharad, et al. “Companies on the Move: Rising Stars from Rapidly Developing Economies Are Reshaping Global Industries.” Boston Consulting Group, January 2011.

3 Kumar, Nurmalia. “How Emerging Giants Are Rewriting the Rules of M&A.” Harvard Business Review 87, no. 5 (2009): 115–121.

4 SEC Form 20F, 2002, retrieved from www.vale.com

5 Hooijberg, Robert, and Lane, Nancy. “Vale: Going Global (A).” International Institute for Management Development, Lausanne, Switzerland: IMD Business School, IMD-4-0312, 2009.

6 From an interview at the Global Leadership Forum, October 2008.

7 Kumar, “How Emerging Giants Are Rewriting the Rules of M&A.”

8 Ling, Zhijun, and Avery, Martha. The Lenovo Affair: The Growth of China's Computer Giant and Its Takeover of IBM-PC. Singapore: Wiley Asia, 2006.

9 Ibid.

10 Schuman, Michael. “Lenovo's Legend Returns.” Time 175, no. 18 (May 10, 2010): 1–7.

11 Millman, Gregory J. “From East to West.” Financial Executive 24, no. 10 (December 2008): 31–33.

12 Schuman, “Lenovo's Legend Returns.”