Chapter 6

Building a Global Business in an Emerging Market

Established corporations typically enter emerging markets for three main reasons: First, they want to sell their products to a large and growing population that has an increasing need for their products and an increasing ability to pay for them. So, when Siemens of Germany entered the Chinese market for high-speed trains, they were lured by the Chinese plans to create the most advanced railway infrastructure in the world. It worked! China now has the largest network of high-speed trains in the world, and has an aggressive plan expanding their rail infrastructure like no other country in the world.1 Germany's Siemens, along with Japan's Kawasaki, France's Alstom, and Canada's Bombardier, are the major suppliers to the Chinese market.

The second major reason that mature market corporations enter emerging markets is to reduce the costs of labor and other factors of production. So when a European IT company moves its software development to India, or when an American textile company closes an old mill in Puerto Rico and opens a new one in Vietnam, they do so to reduce labor costs, even through their primary markets may remain in Europe or the States. This often leads them to the third major reason that corporations enter emerging markets: so they can use their operations in that market as an export platform to serve other countries as well.

But when corporations begin to combine these approaches, the process of entering an emerging market becomes far more complex. Producing products for local consumption requires an increased investment in marketing, sales, and distribution. It may also become more difficult to protect their technology on the ground. New products have to be developed to meet the demands of local consumers. Choices about ownership, control, and legal structure lead to joint ventures, alliances, partnerships, and acquisitions. These decisions also move things along to the point where the local, emerging market operations have an integrated role in a global corporate strategy.

Inevitably, the last pieces of the puzzle to be integrated into the local environment in an emerging market are the capabilities of research, development, and design. Taking this step requires a level of integration that is difficult to achieve and doesn't come without years of hard work to develop the mindset, capabilities, and methods for global collaboration.

Although it is tempting to assume that a globalization strategy can be pursued by focusing primarily on things such as foreign direct investment, legal structures, ownership interests, IP protection strategies, and supply-chain management, in reality the globalization journey is perhaps the biggest cultural adventure of all. And the stakes are very high. Just consider one fact: When General Motors declared bankruptcy in June 2009, their one-billion-plus shares of stock were worth less than a dollar a share. But that year they sold nearly two million cars in China.2 Do the math. Even a year or two later, when their stock had rebounded into the thirties, the value of the total corporation was not much more than the value of the business that they had created in China over the preceding ten to fifteen years.

Building a Business in an Emerging Market

The choice to build a business in an emerging market is one of the most important decisions that a corporation can make. The cycle starts with developing sales and marketing capabilities and production operations. Managing the added sales or reduced costs from entering an emerging market doesn't pose much of a challenge to the global strategy of most firms. But the path from this point to the point when the local operation plays a key role in implementing an integrated global strategy is a demanding one. Let's consider the case of GE Heathcare's efforts to build their Chinese business from a base near Shanghai.3

Leading with a Vision

GE Healthcare first entered the Chinese market in 1991. The story that we tell in this chapter focuses on their efforts to build their anesthesia business. Globally, GE's serious efforts in the anesthesia business began with their 2002 acquisition of Finland's Datex-Ohmeda (D-O), the leading global brand in anesthesia equipment. D-O had sold a limited number of their high-end machines in China prior to the acquisition, but after the acquisition they started production of D-O equipment in Wuxi at the GE Healthcare site.

Anesthesia machines are essential in the operating room: They provide both anesthesia and oxygen to patients during surgery. GE estimated that this market would grow by 8 to 10 percent per year, in part because China's rural health reform was about to bring 80 percent of the rural population—nearly seven hundred million people—into the national health insurance system.

GE's efforts in the Chinese market accelerated with their 2006 acquisition of Zymed, a family-run company also based in Wuxi. Zymed, which GE renamed Clinical Systems Wuxi (CSW) after the acquisition, manufactured and sold anesthesia machines and respirators with technology that had been “adapted” from D-O's technologies. Zymed was the market leader in the Chinese low-end domestic anesthesia machine market, with an estimated market share of 20 to 25 percent. GE later folded D-O into CSW to create the performance segment of their anesthesia business.

Zymed was founded in 1988 by the head of the Chong family. Ten years later, his four grandchildren took over the business and developed it into the market leader. Each of the grandchildren was an excellent salesperson. They divided the China market into four regions, and each took responsibility for one region. In 2004 and 2005, they sold around 900 machines each year; the number reached 1,200 units in 2006, the year Zymed was acquired by GE Healthcare. Guo Song, operations manager of CSW, commented: “The organization structure of Zymed was simple. It had dreams, but no long-term strategy. It had a culture of thrift. It also had good execution, which was based on a transparent rewards system. In its ten-year history, employees benefited a lot financially.”

But like many Chinese family-run companies, Zymed did not pay much attention to internal controls. There was little vision and few control systems. The incumbent general manager had devoted most of his time to sales and marketing, but hadn't created a strategic plan for building the global value-segment anesthesia business. This might not have mattered so much in a fast-growing market in which demand always exceeded supply. But when GE Healthcare decided to buy Zymed, quality quickly became an issue. At one point, they had to stop shipping machines because of customer complaints and quality problems. In addition, their market share was also shrinking because they had downsized their distribution channels to ensure compliance with GE's internal quality guidelines.

So in the second half of 2007, GE appointed Matti Lehtonen as the new general manager of the business. In many ways, from a cultural standpoint Lehtonen was a perfect choice for the GM job. He had grown up in Finland, was trained as an engineer, and had worked with D-O in the past. But he had spent the last twenty-five years in China working in electronics manufacturing and was fluent in Mandarin, Portuguese, and German as well as Finnish and English.

Building the Management Team

Lehtonen soon rebuilt the management team and included a full complement of GE veterans. For example, Maggie Zhang, operations director, had been with GE Healthcare for over ten years, and Zhang Yukun, global sourcing manager, had seven years of GE experience under his belt. Lehtonen also recruited a new finance manager from GE Healthcare China and an HR manager with long GE experience. These team members had a strong identification with GE values, which was essential to the next stage of integration: injecting a strong sense of vision, mission, and strategy into the organization and reshaping the mindset of all employees. These managers also had experience in managing the requirements that came from GE headquarters. Their global sourcing manager noted: “A lot of requirements come from EHS [environment, health, and safety], HR, finance, and other functions. GE culture is very aggressive. You must close lots of things within a very short period of time.”

A Vision-Led Strategy

Lehtonen and his team formulated a vision for CSW and worked out a strategy map, linking the long-term goals of CSW with its operational activities and short-term imperatives. He then worked with the management to create maps for key functions, such as sales and marketing, operations, and engineering. Then they created action plans for the implementation of the strategy maps. The next step was to promote these ideas throughout the company. They convened monthly town hall meetings that involved all employees. At every monthly and quarterly staff meeting and other management events, Lehtonen and his management team reiterated the vision, the mission, and the GE values and continued to refine their strategy maps.

Matti also used some “special tools.” On both sides of his office door, he put up Chinese poetic couplets, which translated as “Pressure Is Motivation,” “Hard Work Is Happiness,” and “Serve the Patient.” The couplets caught everyone's attention, and for Chinese employees, it was interesting and unique to see the traditional couplets outside the office door of a foreign general manager. His office was located near the entry of the office area, so every employee passed by his office each day as they arrived and left.

To demonstrate the kinds of behaviors that were desired and promoted, the management team presented many awards to their people at all kinds of occasions. For example, they gave an award to a cross-functional team, which included people from sourcing, engineering, and operations, when they solved a quality problem in record time, ensuring on-time delivery to their customer. The leaders sent a clear signal that the award was intended to promote: (1) customer and quality priority, (2) cross-functional cooperation, (3) willingness to work hard, and (4) the attitude of making impossible things possible. These priorities also fit well with GE's five growth traits (external focus, clear thinker, inclusiveness, expertise, and imagination). The top priority was external focus, which meant customer and quality were on the top of the list. This focus on quality was a big change from the old sales-oriented Zymed culture.

Tracking the Progress

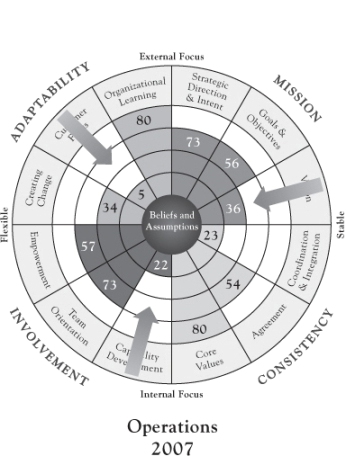

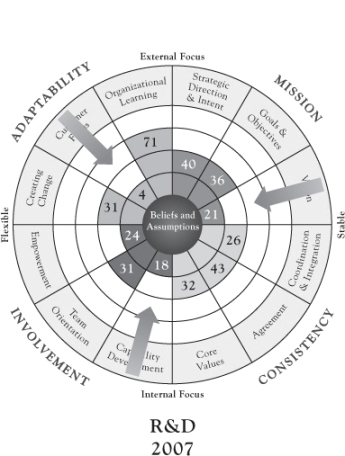

GE Healthcare used our Organizational Culture Survey in late 2007 and early 2009 to track their progress. The results from late 2007, a few months after Lehtonen came on board, are presented in Figure 6.1 for three groups at CSW: Operations, Managerial and Supervisory, and R&D.

Figure 6.1 2007 Culture Survey Results: GE Healthcare, Clinical Systems Wuxi (CSW)

These results present some interesting contrasts. The management scores are the lowest across the board, which appears to reflect the management team's impatience with the status quo and their perception that they had a long way to go on customer focus. Vision and learning were their highest scores, reflecting some of the priorities they had pursued in the first few months. Like many Chinese companies, they also saw capability development as one of the areas most in need of improvement.

The profiles for R&D and Operations are somewhat better, but many of the same priorities for improvement appear. After extensive discussion, the management team decided that they wanted to focus on three major priorities for the coming year: vision, customer focus, and capability development. When we asked Matti Lehtonen what he thought this meant in terms of action priorities, he paused and said, “I think that one of the things that it means is that we should devote more time and resources to something that we are already doing.” What did he mean by that?

To reshape the mindset of all employees, and especially the engineers who designed the products and had the main responsibility for quality, CSW had been sending engineers in groups to hospital operating rooms to see with their own eyes how their products helped doctors save the lives of patients. Kevin Meng, a mechanical engineer, said with emotion, “When I was in the operating room, the idea occurred to me that if the machine didn't work, we could harm people. On the other hand, when the operations are successful, I feel proud of my job because I help save people's lives.”

This one intervention touched all three of the CSW action priorities. Visiting an operating room not only clarified the purpose of their work but also clarified the complexity of the network of customers that they served: the patients, the doctors, the nurses, the hospital, and the insurers. In addition, this program also proved to be an invaluable investment in the capability of their engineers and became a key part of their recruiting strategy to attract new engineers to the organization. Other action plans and priorities also came out of their discussions of the results in the management team, the staff, and the town hall meetings.

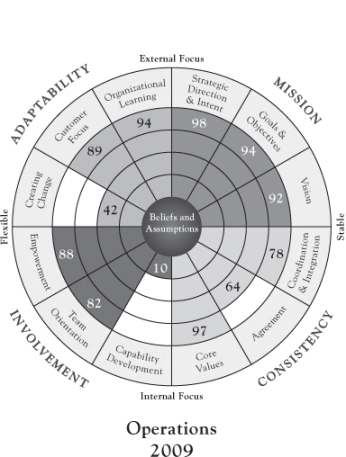

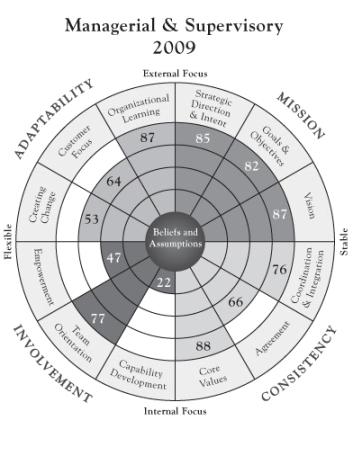

Over the following year, CSW changed dramatically. As the results from early 2009 in Figure 6.2 show, they made great progress in almost all areas. But notably, they also clarified their focus on their biggest challenge, capability development. Especially in R&D and engineering, CSW was in a fierce competition for talent.

Figure 6.2 Comparing 2007 to 2009 Culture Survey Results: GE Healthcare, Clinical Systems Wuxi (CSW)

One Culture? Or Three?

The discussion of the survey results once again focused the company's attention on the four different groups of people who made up the organization: the old D-O culture, the old Zymed culture, the GE culture, and those newly hired from the outside. For those from the D-O culture, joining CSW seemed like a step down—the CSW product line was focused on the value-segment and the machines were not nearly as sophisticated, or as expensive, as the former D-O line. Those from Zymed were not accustomed to processes and systems and felt like these demands slowed them down at every turn. They were more sales-oriented, resourceful, and entrepreneurial—and also more accustomed to waiting for instructions from their bosses. The GE veterans among them struggled to think through how to keep the business running while bringing it into compliance with GE's global guidelines for process discipline and quality. The newcomers? They were often disoriented and a bit confused with the complexity of the situation.

Juggling three different cultures made the development of an integrated process very difficult. There were at least three strong influences on any attempt to create a standard unified process. GE, a process leader, had strong global efforts under way to create common processes among all of its subsidiaries. D-O, a leading brand in the anesthesia business, had its own advanced process discipline, which was quite different from the new unified GE process. Zymed had few clearly articulated processes, but it had a well-established way of doing things. This made it very difficult to create a “clean slate” advantage. Kevin Wu, a mechanical engineer who worked with Zymed before the acquisition, commented, “The new [GE] process is developed based on U.S. FDA requirements. Its level is just too high for our low baseline.”

Lucy Jing, engineering manager, admitted that the new GE process slowed down the working pace of engineers, though she insisted the process would be an advantage in the long run. But the new process did frustrate engineers. Kevin Wu said, “It seems no one realizes how much a good process means to engineers. My understanding is that a good process is like a signpost on the highway. With a good process, you'll know clearly how to do things…Engineers are those people who like to ask ‘why?’ and find the answer…But we have neither clear signposts nor people answering the question here…sometimes you have to spend more than a day to do something that can be done in one hour without the process.”

Kevin Meng, a mechanical engineer from D-O, echoed Kevin Wu's words: “We can't use the D-O process, as it doesn't have a supporting system here. But the new process is not clear. When you get lost with the process and ask someone else, it seems no one knows the direction.”

Quality Improvement or New Product Development?

With a large installed base of the former Zymed products, CSW continued to sell and service these products. The former Zymed engineers had initially imitated the design of the D-O products without understanding all of the underlying design principles. So it was difficult, if not impossible, to trace the problems back to the original blueprints. Thus, whenever they received a customer complaint, it went to the engineering department. The engineers had to figure out what the problem was and develop a solution.

For GE Healthcare and CSW, every customer complaint was a serious issue. This meant that quality issues consumed most of the engineering resources and compromised the engineers' product development efforts. Engineering Manager Lucy Jing said, “We have to put about 90 percent of our engineering resources on maintenance. If I could start from scratch and put the 90 percent of the engineering resources on new product development, we could reduce quality issues by 80 percent.”

But CSW just could not just put aside customer orders and customer complaints. Nor could they simply allocate more engineering resources to new product development. Although GE was supportive of the business, actually getting approval for a new head count was difficult. Even when they did, it was difficult to attract talented, experienced engineers to Wuxi—a second-tier city of only five million people, two hours' drive from Shanghai. CSW had started to develop new products, but the pace was slow due to the lack of engineering resources. Project Leader Google Wu summarized their progress: “We have milestones for new product design, from M0 to M5. Now our new product is at M0, the stage for collecting information, defining products to meet market needs.”

Toward a Global Strategy

Despite all of the struggles, in 2008 CSW managed to double their sales volume in terms of units installed in hospitals over their 2007 sales volume. Exports to India and increasingly to China and Russia had grown to 40 percent of their total volume. Progress on a new anesthesia machine that would create the foundation for a global, value-segment equipment business was slow, but by 2010 CSW had introduced their new “9100c” model and was shipping this to emerging markets all over the world. Although this machine still did not meet the FDA requirements necessary for the U.S. or Western European markets, it was a massive step forward and laid the foundation for resolving the quality and process problems that CSW needed to address to build a global business from a base in Wuxi.

Lessons for Leaders

Within five to six years, GE Healthcare made dramatic progress in China. They established a strong position in the local market and then started an export business, focusing first on India and Brazil and then on Russia. Building from these accomplishments, they played an increasingly important role in the global anesthesia business by establishing Wuxi as the center of the value segment in the anesthesia business and developing new products to serve the global value segment from that base. The leader of this business, Matti Lehtonen, was then promoted to lead GE's global anesthesia business. Let's look at some of the lessons that we can learn from their progress.

Vision Wins Again

As with several of the other stories, this case is a strong testament to the power of a compelling vision. At the beginning, Lehtonen's choice to lead with vision—rather than strategy, process, quality, or sales—was not necessarily a popular or a well-understood decision. Many of the staff in Wuxi, as well as executives in other parts of GE, questioned the wisdom of this approach and were often impatient with the time spent talking about the vision in their town hall meetings.

But the time spent on the vision actually proved to be essential to the transformation. The common purpose that they articulated in their town hall meetings gave a reason for the future strategy of the business. It gave a reason for integrating the production processes for D-O and Zymed. It gave a reason for the urgency of resolving their quality problems as quickly as possible, at the same time that they were striving to accomplish product upgrades and a complete product redesign. The vision helped them make sense of the intense mix of short-term and long-term priorities that they faced. Longer term, this focus on the vision also created the foundation for Wuxi to lead the value segment of the global anesthesia business.

At the beginning it was very difficult to devote the time to a long-term vision. It was even harder to devote the time to the town hall meetings when the urgent quality problems of the day were still unresolved. But in the end this strategic choice paid off handsomely. A little vision often goes a long, long way.

Organizational Subcultures Are Everywhere

In many ways, the biggest cultural hurdle to overcome was not the global challenge of an American multinational building a business in China. Rather, it was the challenge of bridging the gap between the organizational cultures of Datex-Ohmeda and Zymed. Both of these organizations were Chinese, but they were as different as a Silicon Valley start-up and a Rust Belt manufacturer, and they had a history of being competitors. Keeping both operations running while integrating them into one was the fundamental challenge. Without succeeding at this first step, none of the rest would have been possible.

The “American” part of this cultural mix is also very interesting. At the beginning of this story, the GE global standards seemed highly ambitious, if not totally unattainable. Managing the relationship with corporate headquarters mostly meant a lot of administrative work to comply with the corporate standard. But GE's FDA-driven standard was, in the end, critically important to bringing D-O and Zymed together. Without the GE standard, there would have been no common point on the horizon toward which both D-O and Zymed could evolve. There are many aspects to the American culture besides GE's process discipline, but that was certainly the aspect of “American” business culture that had the biggest impact in Wuxi.

It's extremely important to understand national differences in work habits and organizational cultures. But if there is one strong argument against the dominant force of national culture in determining workplace relations, it is the huge variety of organizations, each with their own unique culture, that exists in every country in the world. Individual organizations have unique histories and contexts, and they grow in unique ways. And within each of those unique organizations there is a unique mix of subcultures within cultures that are a key part of the logic by which the parts fit together. This all adds to the complexity. All Chinese organizations are no more alike than all American organizations or all Swiss organizations. So it is essential to focus on the unique aspects of each individual firm as we move around the world and to pay attention to the individual subcultures within them.

Acquiring a “Competitor”

One of the most interesting parts of this case is the fact that when GE acquired Zymed to expand into the Chinese market, they were actually purchasing a company that had originally “adapted” its technology from D-O.4 Zymed then further developed this technology to fit the Chinese market. This was an unusual acquisition strategy, although not without precedent. The upside of this strategy is clear: It was attractive to eliminate an imitator and a competitor in the local market, and it was also attractive to quickly gain the market presence and distribution network that Zymed had established. An organic growth strategy would have taken much longer.

And in the end, surprisingly few of the integration challenges stemmed from Zymed's “adapting” of the D-O technology. By the time Zymed was acquired by GE, there were enough differences in the technology that the situation still required the definition of a new set of GE-based design and production principles. This suggests that, beyond the usual challenges of merging two organizations that had been competitors in the past, GE paid no real penalty—nor gained much real benefit based on the prior connection between Zymed and D-O technologies.

Building a Global Business in an Emerging Market: Beyond GE Healthcare

The study of how multinational firms expand in emerging markets has a long history. But within the past decade, this expansion process has accelerated dramatically. This increase in speed and complexity has put a premium on a company's ability to manage cultural change and integration. The clash of core beliefs and values and daily work practices has become a part of the daily routine.

The capability to manage cultural complexity is a powerful force. When harnessed, it can be the crucial element in creating a global corporate culture. When ignored, cultural fragmentation can become a major barrier to both strategic and operational integration.

The Theory of Globalization: From the Past to the Future

Past approaches to globalization have pointed to three distinct stages of entering a new market—ownership, location, and internalization.5 These stages are often used to describe the evolution of a firm's globalization strategy and their specific approach to entering an individual market. Firms often start to enter an emerging market by exporting from their base in a mature market. Their next step is to move to ownership—they acquire a firm in that market or create a firm to represent their business there. The next stage after ownership is localization, as the firm gradually moves production and later engineering and local design functions to an emerging market, to either serve that market or serve as a base to export from that market. During the final stage, internalization, the firm moves toward creating an integrated operation in the emerging market.

But today, these basic economic decisions tell us very little about a firm's chances for success in an emerging market. Ownership is important in an emerging market to establish the firm's presence and commitment and to gain access to local resources. Location is important too. A firm doesn't need to own everything or to be on every street corner in every emerging market, but firms can no longer achieve a visible presence without creating strong local organizations.

The third stage, internalization, has become much more important to global expansion than it has been in the past. The quality of internalization has become the critical frontier of globalization. Global corporations must demonstrate the superiority of their approach to building a local organization. The quality of that organization is what will determine the success of the firm.

Consider the experience of Pfizer in China and their joint venture with Shanghai Pharmaceutical. This past decade, Pfizer took the lead among pharmaceutical companies to establish an R&D base in Shanghai. Many companies have tried to avoid revealing their critical research capabilities in China in order to protect their intellectual property. But more recently, Pfizer has moved all of their antibacterial research to this location. Why do they continue to invest in this way? There are many attractions, but perhaps the most compelling factor is the incredible stream of life science graduates that China will produce this coming decade. Other pharmaceutical companies—such as GSK, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi-Aventis—have also followed this path. This trend points to the importance to Western firms of insourcing world-class knowledge workers, not just outsourcing low-wage manufacturing jobs.

Or consider GE's John F. Welch Technology Centre in Bangalore, founded in 2000. GE saw the limits of outsourcing and started to build their own technology centers that could provide them with all of the advantages of India's market for knowledge workers. Ultimately, the success of these strategies depends on the ability of multinational firms to become global “magnets” for top talent. As they develop the capability to compete for top talent and use that talent to build key components of their global organizations in emerging markets, they will establish themselves as global leaders.

Culture as a Competitive Advantage

In the early days of the culture movement, researchers pointed out that the unique culture of a firm was one of its most important resources.6 It takes a long time to build a positive culture, and it takes a lot of energy to sustain it. So a new entrant in an industry, seeking to build a competitive organization, had their work cut out for them. They could license the technology, build the production capability, create the distribution network, and rent the office space. But none of this would give them any sustainable competitive advantage unless they could also build a unique culture that integrated all of the pieces of this puzzle with a common logic that was near and dear to the hearts and minds of their people.

This is quite a challenge, because today, on a global scale, the cultural bandwidth to create an integrated organization is in scarce supply. This is partly because the skills necessary to integrate a global corporation are actually quite specific to that corporation. Sure, we always need to hire great talent from the outside, but organizations that aren't creating this capacity internally will always be at a disadvantage. This is especially true when a firm tries to make the transition from playing catch-up to becoming an industry leader with no one left to imitate except themselves.

This challenge is clearly greatest in emerging markets. The race is on. The struggle to win the war for talent and simply get the right person into the right job often leaves us exhausted at the end of the day. And there are still many more positions to fill! But the real target, as we enter this exciting new era of global competition, will always be to build exceptional organizational capabilities, on the ground, that build the firm's competitive advantage for the future.

Notes

1 Gifford, Rob. “China Leads World in High-Speed Rail Tracks.” National Public Radio. November 16, 2010. http://www.npr.org/2010/11/16/131351045/china-leads-other-nations-in-high-speed-rail-tracks

2 Barboza, David. “G.M., Eclipsed at Home, Soars to Top in China.” New York Times. July 21, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/22/business/global/22auto.html

3 Denison, Daniel R., Xin, Katherine, and Zhang, Lily. “GE Healthcare Life Support Solutions (A): Entering a New Global Market.” Lausanne, Switzerland: IMD Business School, IMD-3–2074, 2009; Denison, Daniel R., Xin, Katherine, and Zhang, Lily. “GE Healthcare Life Support Solutions (B): A Vision-Led Integration.” Lausanne, Switzerland: IMD Business School, IMD-3–2075, 2009; Denison, Daniel R., Xin, Katherine, and Zhang, Lily. “GE Healthcare Life Support Solutions (C): Positioning for Quality and Growth.” Lausanne, Switzerland: IMD Business School, IMD-3–2076, 2009.

4 As noted earlier, when GE acquired this company it was named Zymed. After the acquisition, they created the name CSW (Clinical Systems Wuxi) to refer to the combination of Datex-Ohmeda (D-O) and Zymed.

5 Dunning, John H. Multinational Enterprises and the Global Economy. Workingham, UK: Addison-Wesley, 1992.

6 Barney, Jay. “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage.” Journal of Management 17, no. 1(1991): 99–120.