Chapter 5

Exporting Culture Change

Every global organization faces the same challenge. It doesn't matter whether they are American, Dutch, Swiss, Chinese, German, French, Japanese, Brazilian, or Indian: their organization started in one place and grew successfully from there. The core logic and the established culture of the firm reflect those origins. As their organization has thrived, it has grown far beyond their initial origins and aspirations. But in the process, they start to bump up against a basic dilemma: How do you export the spirit, the essence, and the principles that form the foundation of a successful organization to a new context without falling victim to the folly of imposing home country habits in a new setting where those habits don't fit very well?

Examples are everywhere. How do you sell hamburgers in India? Yes, management consultants are fond of saying that “sacred cows make the best burgers,” but that doesn't help McDonald's create a product strategy for Hindu customers.1 When Domino's Pizza first entered Germany, they tried to stick to the formula that had worked for them in the States. But they quickly found out that most German men would not take their families out for pizza if they couldn't sit down at a table and have a beer. So they had to change their plans to adapt to the local habits. In Chapter One, we talked about the fact that IKEA's flatpack strategy made it nearly impossible for them to really prosper in the commercial furniture market. However, they have successfully introduced lingonberries as an icon of Swedish style in many different countries. Building a successful global corporation always means successfully importing and exporting elements of an organizational culture across national boundaries.

When Japanese companies first began building cars in the United States in the 1980s, they tried, with mixed success, to introduce Japanese work practices into their American factories. One practice that didn't transfer very well was the Japanese habit of workers doing calisthenics together before starting work in the morning. I never understood why this practice worked so well with Japanese workers until our oldest child Roland went to fifth grade in a Japanese public school. Every morning, even in the winter, the students would line up in the playground at the beginning of the day. Their teachers would call roll, make announcements, and talk about the plans for the day. While they talked, the children shivered, but did not dare to complain. When the teacher stopped talking, the exercises would begin! Slowly, the day would come alive, as the children started to warm up together.

So for a Japanese worker, morning calisthenics has a lot of meaning with deep roots in their national culture. But the same practice had very little meaning for the American workers, so it didn't achieve the intended purpose. These stories are good reminders for all of us that meaning makes sense only in context. When we change context, we always need to make sure we connect.

Can Culture Change Be Exported?

A successful transformation of any one part of an organization is a major achievement. But translating those changes to another part of the organization is a far bigger challenge. Achieving uniform change on a global scale is the biggest challenge of all. It is difficult because organizations seldom change at the same pace throughout the world. Many firms make the mistake of assuming that they can roll out programmatic change on a global basis. In our experience, it is quite different. All change is local, and then multilocal, long before it becomes global. Learning from local best practice, so that the most important lessons are transmitted to the entire firm, is the hardest part of the change process. The seeds of the future always exist in the present, where they are waiting to be discovered and leveraged on a global scale.

This perspective implies that transforming a global organization requires successful change in one part of the organization to be “exported” to other parts of the firm and then integrated into the local context. Is that really possible? What does it take to make this process successful? Let's have a look at one example of a successful transformation in the United States that was then “exported” to Europe.

Transformation and Turnaround

In 1998, GT Automotive acquired S&H Fabrication and formed the HVAC Division (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) to serve the automotive market.3 GT was a private company that originated in 1919 in Birmingham, England, as Tube Investments Ltd. From the start, GT was an industrial company specializing in products that carried fluids through tubing, such as braking systems, fuel systems, and HVAC systems. Through the decades, the company grew organically and through acquisitions (the company is now owned by a private equity firm). By 2009, they operated over a hundred facilities in twenty-seven nations with sixteen thousand employees on six continents. Of around $3 billion in annual sales, Europe generated 50 percent; North America, 35 percent; and the remainder came from Asia and South America. GT is a supplier to every major auto manufacturing company, and General Motors is their largest customer.

In 2002, Tim Kuppler became general manager of GT's North American HVAC Division. Kuppler was a veteran employee of GT, having joined the company in 1992. His experience in the company included ten years in quality assurance, followed by a stint in fuel systems. He inherited the leadership role in an organization that had gone through a lot of transition and was the ninth leader to take charge of the organization within the last five years!

Since the S&H acquisition, all administration has been centralized around the North American headquarters near Detroit. Many long-term employees felt that the innovative and entrepreneurial culture of S&H had been replaced with the slow, bureaucratic culture of GT. With tight functional silos and limited workspace, some of the staff even found themselves working in trailers in the parking lots. Furthermore, as the smallest division of GT, HVAC seldom got the attention that they needed from the top GT executives. One HVAC manager noted, “We were like the red-headed stepchild of GT.”

Tracking the Progress

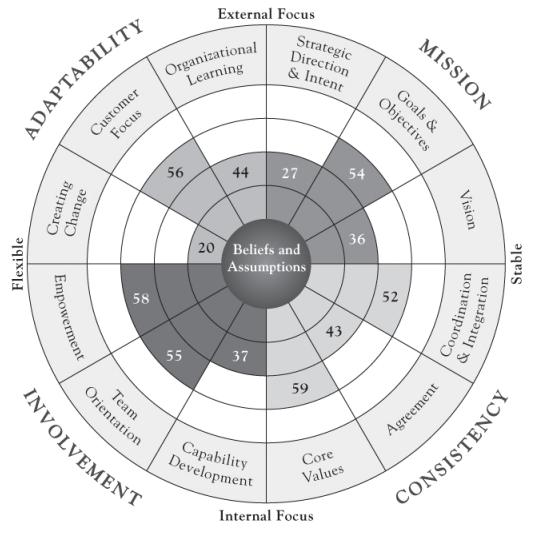

Our Organizational Culture Survey had been used by GT for four years before Tim Kuppler became GM of HVAC.4 Given what he observed in the early days of his tenure as general manager, he believed that this approach could be helpful in diagnosing the division's problems and helpful in improving the business. The message from a survey of all the division's salaried employees in 2003 was clear. These survey results are presented in Figure 5.1. The results showed a weak sense of direction and a lot of uncertainty about the division's capabilities to make the changes required to become more competitive. They needed a sense of their future—and a plan for how they were going to get there.

Figure 5.1 2003 Culture Survey Results: HVAC North America

Involvement Meetings

GT's approach for moving from diagnosis to action has important implications for every organization. They brought all salaried employees together for a day-long “involvement” meeting that would serve as a platform for understanding the division's survey results and starting to plan the changes that would address their major problems.

From the beginning, there was pervasive skepticism. In the past, meetings of this type had led to few real changes. But Kuppler's enthusiasm for making HVAC North America a better place to work was infectious. Their first involvement meeting started with a review of HVAC history. After that, the leaders presented the culture model and the survey results. No one was surprised by the news that they had some work to do.

As a part of this meeting, the leadership team proposed a vision statement for the HVAC staff to consider. Small work groups then reacted to the proposed vision statement, offering suggestions on enhancing the customer relationship strategy and suggesting ways to address the issues raised by the survey. The process invited and rewarded everyone's participation in helping to determine the future strategic direction of the company. The ideas that came from these small-group discussions were presented to the entire group, with lots of suggestions for action steps and follow-up.

A few months later, a second involvement meeting was held to evaluate progress against the goals that they had set in the first meeting. Both management and employees were held responsible for formulating ideas and implementing change. As this cultural transformation started to gain momentum, attitudes started to shift throughout the organization. The involvement meetings became a twice-yearly event for employees, who started to look forward to these events as great opportunities to catch up with colleagues and contribute to shaping the future of the division.

Source: Denison and Lief, 2009a and 2009b.

Business Teams

But involvement teams alone were not enough to drive the transformation. To sustain the momentum created by the involvement meetings, the next step was to capture that energy and direct it at a set of core business issues. To do this, they created a set of business teams focused on the specific changes required to enhance the customer experience at HVAC. Five business teams were created, ranging from five to twenty individuals, and every salaried employee was involved in the work of at least one of those teams. They thought through the choices for the best structure, composition, goals, responsibilities, and metrics of each of the new business teams. Leadership selection and operating procedures were left to the discretion of each team. The only requirements for each team were that they should: (1) meet regularly, to encourage communication and engagement; (2) participate in a charity function annually; (3) update their objectives on a quarterly basis; (4) report progress at monthly business meetings; and (5) maintain a site on the company intranet. To keep each other informed, the business teams were invited to present their best practices and current challenges at monthly all-team meetings.

These business teams overlapped quite a bit with the existing organizational structure. But their purpose was not just to have every department form a business team; rather, it was to create a new way of working, in keeping with the overall purpose of “enhancing the customer experience at HVAC.” One important feature of this approach was that the business teams were not simply the leadership teams of the departments or units. Instead, the members of the business team were usually one or two levels down in the organization from the leaders of the department in which the business team was being formed. This “action team” approach is usually very effective, because it creates a team of knowledgeable and experienced individuals with a strong stake in leading the organization into the future, rather than an intact leadership team that may be tempted to get distracted by defending the decisions of the past.

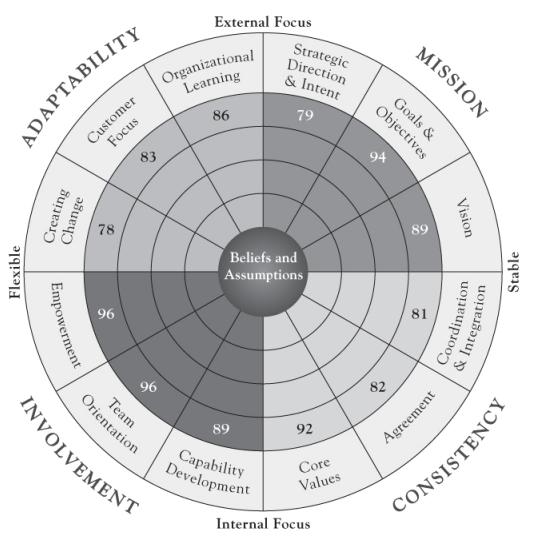

After a year of this process, the leadership team and the staff were actually a little surprised by their progress. Their 2004 survey results, presented in Figure 5.2, showed substantial improvements in every category. HVAC beat their profit plan by 20 percent in 2004, and quality and safety performance also improved. The efforts of Kuppler and his team drew the notice of TI corporate executives. They had created a cultural transformation of their own and had led a significant turnaround in the business. HVAC was no longer the “red-headed stepchild” of TI.

Figure 5.2 2004 Culture Survey Results: HVAC North America

Be Careful What You Wish For

As a result of these successes, Kuppler was asked by TI to take on global responsibility as vice president and general manager for the HVAC Division. Although he was convinced that he needed to implement a change agenda in his new position, he wondered if he should take the same approach in this new context. Corporate culture would clearly be an issue, but this time national culture would be too. In his new global role, he would have to deal with the complexity of HVAC's operations in eleven countries around the world. The workforce was scattered over a wide geographic area, and the influence of diverging national cultures on the corporate culture would make the job much more difficult.

His initial idea was to extend the successful change process that they had used in North America but to continuously modify it based on the lessons they learned in each country. Europe was clearly the top priority. HVAC had manufacturing operations in Spain, Italy, and the Czech Republic, with commercial operations headquartered in Heidelberg, Germany. There were big cultural differences among these locations. Would the same approach that brought an enhanced work environment and impressive financial performance in the United States also prevail in this diverse set of European settings?

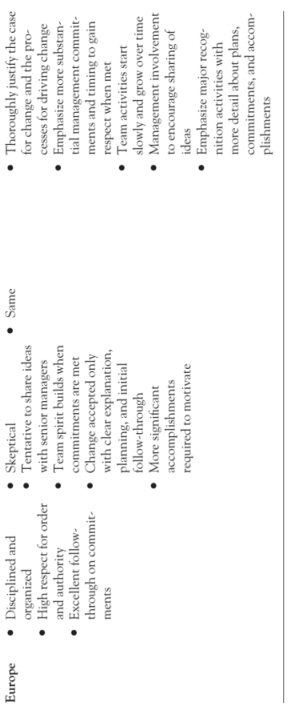

Kuppler sensed that the strength of the European organization was in its disciplined approach, respect for authority, and dedication to following through on tasks. However, he also found that employees seemed very skeptical of new initiatives and, therefore, less willing to candidly share their feelings and ideas. This group needed convincing that real change would come, no matter what they did or how much they talked. But this time the job was also more complex because of the five operating languages that were used in the European facilities. He had his work cut out for him, but he had the strong support of the global HVAC leadership team he had created with representatives from around the division. Table 5.1 presents a summary of the similarities and differences between the United States and Europe.

Table 5.1 North America/Europe Culture Change Comparison: GT Automotive HVAC

The survey results for Europe in 2004, presented in Figure 5.3, were actually more challenging than the initial survey results in North America in 2003. Consistency, which was not so much of a problem for North America, turned out to be the weakest trait for Europe, reflecting that there was little agreement among the different locations about what was needed to create one global HVAC business. The survey results were available in June 2004 and the first involvement meetings were scheduled for that same month. Once again, the agenda for the meeting included the presentation of the group's results and votes on establishing priorities for action plans. A vision and strategy for the European unit was discussed and clarified. The next meeting was scheduled for November 2004.

Figure 5.3 2004 Culture Survey Results: HVAC Europe

The reaction to these results varied quite a bit by location. In the commercial center in Heidelberg, home to the sales teams and the design groups, there was a lot of skepticism about the results and their implications for change. In their first involvement meeting, it took a long time to gain a consensus to move forward. But once they had reached an agreement, the Germans tended to move forward with discipline and structure. The manufacturing locations in Italy, Spain, and the Czech Republic, in contrast, had initial discussions that were more receptive to the results and the need to take action. Their consensus came more quickly, but their follow-through was less structured.

The low scores on agreement that appeared in their results pointed to a set of issues that could not be resolved using a location-by-location approach. This led to a series of discussions among managers from the four locations about coordination and agreement between the customer, the sales process, the design team, and the manufacturing sites. This kind of discussion had never happened before. It forced them to sort out issues that had several layers of culture. With the Germans, the Italians, the Spaniards, and the Czechs all in the room, there were several layers of culture to consider: the center versus the locations, sales versus manufacturing, design versus production, Northern versus Southern Europe, and Germany versus the rest. All of these factors had an important influence on the values of the team members and their ability to work together. Nonetheless, these discussions led to a set of cross-functional metrics—such as launch quality, sales, and margins—that forced a new level of collaboration in the European organization.

As in North America, Kuppler worked quickly with his leadership team to create business teams throughout Europe to follow up on the momentum created by the involvement meetings. In all, thirty business teams were established across the global business unit by the time he was finished. A summary of the global business teams that were created is presented in Table 5.2. Each of the teams was required to develop a standard set of metrics that they would use to report their progress on a regular basis. Each team was also required to update everyone through their team webpage on the company intranet. Although this process had many similarities with the process used in the United States, it was also very flexible. Kuppler noted,

This was not a tightly planned effort from the start. It was more watching how things evolved over time and continuously obtaining employee feedback for improvement as we defined and updated our priorities. We learned what to emphasize as we went along. And we got a better appreciation for how culture touches everything.

Table 5.2 HVAC Global Business Teams

| Global

Core Engineering Technology Commercial Business Systems Purchasing Estimating Europe GM / Fiat / Suzuki Strategic Customers Tier 1 + Truck Customers Jablonec Plant Tauste Plant Cisliano Plant North America GM DCx Delphi Air International Ford Prototype Employee Involvement Design Tool Group Plants: 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, Service Sanford Plant Asia Asia Commercial Anting, China Plant |

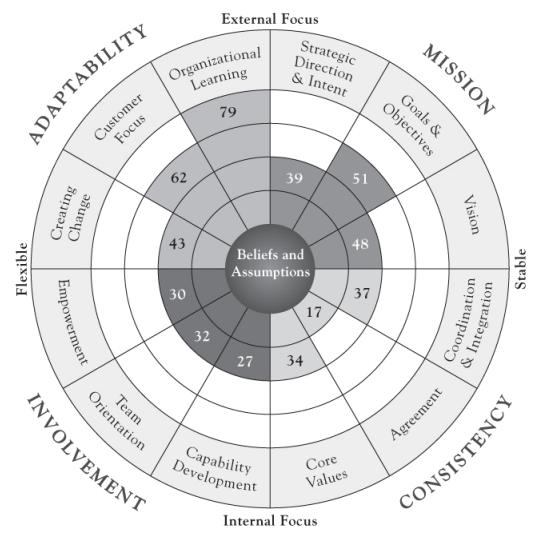

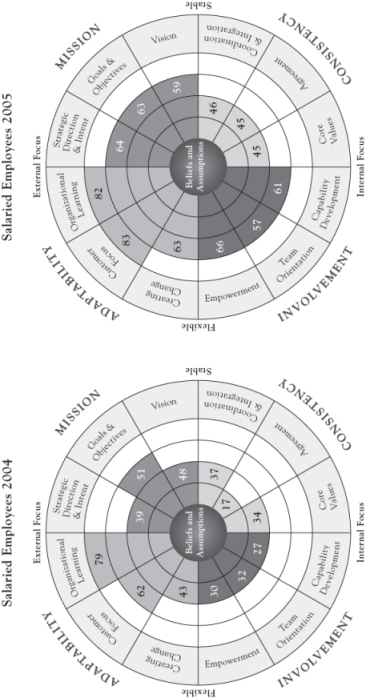

The changes from 2004 to 2005 were dramatic. Much improvement was noted, with better results in every category. There was still much to be done, particularly in the area of Consistency—Core Values, Agreement, and Coordination and Integration—but overall the leadership team had much to feel good about. As reflected in Figure 5.4, HVAC operations in Europe moved forward in a variety of ways. There were signs of progress in everything from financial performance to new business wins to safety, quality, and strategy implementation.

Figure 5.4 Comparing 2004 to 2005 Culture Survey Results: HVAC Europe

Kuppler came to believe that the only way to survive as a firm in the auto industry was to strengthen the team, building individual leadership capabilities through regular feedback for senior managers, routine developmental reviews for all managers, exchange programs between locations, and a significant expansion of the opportunities for training and development. But it was also important to line up behind one comprehensive, well-understood vision. Regular follow-up and communication with respect to progress toward that vision was also important in order to sustain the effort. These changes led to considerable improvement in the performance of the business and made TI a healthier, more enjoyable place to work. Table 5.3 gives an overview of the changes in performance that occurred between 2002 and 2006.

Table 5.3 Improved HVAC Culture = Improved Results

| 2002 | 2003–2006 | |

| Profit | On plan | 2003–2005: 10 percent better than plan

2006: NA restructuring |

| Quality | Thirty-seven parts per million (PPM) | Single-digit PPM |

| New Business Wins | Two non-GM wins in prior five years | Over 20 non-GM wins |

| Globalization | No Asia presence | Four programs won in Asia

New plant established in China |

| Global Leadership | Eight leaders in five years | One leader |

| Global Coordination | None | Leading TI business

Global strategies Global teams Global intranet Global business processes Global product designs Global manufacturing processes |

After successfully leading the HVAC business transformation in North America and Europe, Kuppler went on to head TI's entire operation in North America, with responsibility for the brake and fuel business as well as the HVAC Division. He introduced his leadership and teamwork ideas to this work unit as well. In mid-2008, following the appointment of a new corporate CEO and the implementation of a new global organizational structure, Kuppler left TI. But looking back on his efforts, he reflected,

The most important factor in our success was the freedom given to me and our leadership team by my boss, Rich Kolpasky. He had confidence in me and my ideas. He trusted me to run the businesses the way I thought best. After reading literally hundreds of leadership and management books, I had ideas I wanted to try out. He gave me the opportunity to follow my instincts and knowledge. And the results were satisfying—a more involved workforce and substantially improved performance when we initially managed the culture change.

Lessons for Leaders

GT Automotive's success, using a change process that was first developed in the United States and then applied in Europe, came as quite a surprise to the organization and to industry observers. Isn't national culture supposed to be a nearly insurmountable barrier to creating a truly “organizational culture”? Doesn't each national culture require its own independent approach to creating the buy-in required for successful organizational change? Let's consider some of these questions as we look at lessons that we can take away from this example.

Do What You Know Best

Although it is clearly true that different national contexts may require very different approaches to organizational change, this case is a good reminder of the fact that doing what you know how to do with honesty, openness, and integrity can go a long way. Leading with curiosity, respect, and a clear set of principles that you are trying to apply in the new context can be quite successful.

When we use an approach that is familiar to us, we are able to more quickly create a structure that will apply some core principles to have a large-scale impact. In the United States, Kuppler created a structure of weekly business team meetings, monthly business meetings, quarterly objective updates, quarterly global strategy meetings, and twice a year an involvement meeting with a social event in the evening. This set of activities reinforced the change process and created a new level of teamwork. This architecture allowed the organizations in both locations to manage the transition from the insights and dialogue of the involvement meetings to the action orientation of the business teams.

The logic of this approach and the credibility that it had based on the success in North America provided an irresistible advantage to the change process. It didn't take a lot of time to gear up, and Kuppler and his colleagues were very familiar with the key leverage points in the process as it unfolded. The integrity of this structured approach seemed to outweigh the needs for a more unique approach to each country and location.

But Adapt as You Go

On the other hand, it is very important to understand that the lessons about “doing what you know best” were about expressing the same set of principles in the new European context, and not about enforcing adherence to TI's practices on the ground. There is a big difference between consistency and compliance. One interesting example of this was the reaction to the “service learning” component of the change process in the United States and Europe. In the United States, spending a day together as a team working on a charity was a big part of the process. It built a commitment among the team members that they were a force for good and that they were working together for a purpose that went beyond their quarterly business targets. But in Europe, for a number of reasons, this component of the process was not as well received. So they changed this part of the process and concentrated their efforts on other ways to build teamwork and commitment.

It is also critically important to remember that expecting to find a uniform approach to the change process is mostly wishful thinking. Change almost always happens at different rates in different places. As seductive as it may seem to roll out a global change process with the expectation of a unified approach, it almost never happens. Consistency in the change process is often worth striving for, but it seldom happens. Change strategies designed to create momentum will beat change strategies designed to create uniformity every time.

Exporting Culture Change: Beyond GT Automotive

GT provides us with lots of good examples of the challenges of exporting change across national boundaries. It is hard work, but as this case shows, it is definitely possible. So despite the hard work associated with leading global culture change, organizations keep trying to overcome the realities of fragmented, disconnected “global” organizations to try to create better integration. Let's consider some other authors' perspectives on this issue.

Which Is Stronger: National Culture or Organizational Culture?

As many authors have noted, national cultures have a depth that organizational cultures can never achieve.5 It takes hundreds or even thousands of years to develop a national culture, and that process creates roots that go far deeper than any that could ever be created by an organization.6 However, Freud reminds us that “love and work are the cornerstones of humanity.” He didn't mention anything about which passport we carry!

There is no question that nationality has an influence on those all-important work habits that are so central to our identities. But our habits are also shaped by many other aspects of the context that we work in: the organization we join, the industry we work in, the profession we have chosen, and the work group we are a part of. All of these factors have a strong influence on our identities—as the following situation illustrates.

Two poets walk into a bar, followed by two engineers. One of the poets is French and the other is English. Same with the engineers. The four of them start talking. What do you think will have the biggest influence on the approach that they take to the issues they discuss: their nationality or their profession? What if they are talking about building a bridge? Or writing a song? How about EU fiscal policy?

The answer, of course, is that this depends on the issues they are discussing. But when it comes to organizational culture, many of the values, beliefs, and work practices that we develop are quite specific to the organizational context that we work in.7 Occupational culture, for example, is also a strong influence. It is always fascinating to see the reaction of a roomful of executives from all over the world when they are grouped by function. There is almost a sigh of relief that now auditors can talk to auditors, pilots can talk to pilots, engineers can talk to engineers, and sales guys can talk to sales guys. The influence of nationality on work habits fades away fast.8

These connections of common organizational experience provide a basis for creating a change process that spans national boundaries. Lessons learned in one country can sometimes be transferred across boundaries to build momentum for change.9 National culture has a strong influence on the way that we organize and the way that we lead. But it is certainly not the only influence.

Clear Direction Makes All the Difference

The lessons from this chapter are also a good reminder that setting a clear direction has a strong influence. A long debate over the right or the wrong way to proceed is seldom a motivator. Interestingly enough, setting a clear direction is so important to a team, a group, or an organization that the energy and focus can sometimes transcend the importance of the actual direction itself. Scholar Karl Weick tells this story:

The young lieutenant of a small Hungarian detachment in the Alps sent a reconnaissance unit into the icy wilderness. It began to snow immediately, snowed for two days and the unit did not return. The lieutenant suffered, fearing that he had dispatched his own people to their death. The third day the unit came back. Where had they been? How had they made their way?

Yes, they said, we considered ourselves lost and waited for the end. And then one of us found a map in his pocket. That calmed us down. We pitched camp, lasted out the snowstorm, and then with the map, we discovered our bearings. And here we are.

The lieutenant borrowed this remarkable map and had a good look at it. He discovered to his astonishment that it was not a map of the Alps, but a map of the Pyrenees.2

Setting direction and building momentum are essential to any change process. Momentum can build across national boundaries if we follow those elements of the culture that we share in common—and respect those elements of the culture that we do not.

Notes

1 Kriegel, Robert, and Brandt, David. Sacred Cows Make the Best Burgers: Developing Change-Driving People and Organizations. New York: Warner Books, 1996.

2 At the company's request, we have adopted a pseudonym for this firm.

3 Denison, Daniel R., and Lief, Colleen. “GT Automotive (A): Transforming a Corporate Culture.” Lausanne, Switzerland: IMD Business School, IMD-4–0308, 2009; Denison, Daniel R., and Lief, Colleen. “GT Automotive (B): Building a Global Team.” Lausanne, Switzerland: IMD Business School, IMD-4–0309, 2009.

4 Hofstede, Geert. Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2001. See also Wilkins, Alan, and Ouchi, William. “Efficient Cultures: Exploring the Relationship Between Culture and Organizational Performance.” Administrative Science Quarterly 28, no. 3 (1983): 468–481.

5 Gomez-Mejia, Luis R., and Palich, Leslie. “Cultural Diversity and the Performance of Multinational Firms.” Journal of International Business Studies 28, no. 2 (1997): 309–335.

6 For years, our research team has studied the differences in our culture data from around the world. The shocking finding is that the differences are actually very small. In the Appendix to this book, you will find a more detailed description of these research studies.

7 Apfelthaler, Gerhard, Muller, Helen J., and Rehder, Robert R. “Corporate Culture as Competitive Advantage: Learning from Germany and Japan in Alabama and Austria?” Journal of World Business 37, no. 2 (2002): 108–118. See also Brock, David M., Barry, David, and Thomas, David C. “‘Your Forward Is Our Reverse, Your Right, Our Wrong’: Rethinking Multinational Planning Processes in Light of National Culture.” International Business Review 9, no. 6 (2000): 687–701.

8 Schneider, Susan, and Barsoux, Jean-Louis. Managing Across Cultures. Harlow, UK: Financial Times/Prentice Hall, 2003.

9 Weick, Karl. Making Sense of the Organization. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2001.