Chapter 8

Building for the Future: Trading Old Habits for New

All of the companies that we have studied in this book have viewed their organization's culture as a key part of their ability to compete as a business. Why do they see it that way? We believe they see that the culture reflects the core logic of the organization and the basic mindset of the people and helps define the firm's strategy for organizing. “The way we do things around here” is captured in the traditional habits and bundles of interconnected routines that define an organization's knowledge and capabilities. The culture is hard to understand from the outside and hard to change from the inside.

Many of the most popular definitions of organizational culture have emphasized three different levels of analysis: (1) the deep underlying beliefs and assumptions that are often difficult for insiders to articulate, (2) the values and principles that structure action, and (3) the symbols and artifacts that are visible on the surface for all to see.1 This approach helps us to see that much of the knowledge we have as individuals and organizations is tacit—the knowledge is captured in our underlying beliefs and assumptions, and the knowledge informs our daily actions, but we aren't always very aware of how the two are linked. As in the iceberg we presented in Figure 1.1, most of the real substance lies under the surface.

“If only H-P knew what H-P knows,” said the CEO of a major global consulting firm to us recently. The awareness of a firm's knowledge and how it gets applied is a major challenge in any organization. And it is closely related to the ability of the firm to compete. Consider Ratan Tata's commitment to developing a $2,500 car, the Tata Nano. Rather than viewing the project as an attempt to develop a dramatically less expensive car, Tata viewed their target customer as a family of four who are currently riding around on a motorbike. Tata's tacit knowledge of this market segment was a competitive advantage that no Western firm could ever duplicate. Their mindset was their advantage. The belief that the project was possible was their greatest asset.

Trading Old Habits for New

Although it has become popular to conceive of people and organizations as rational decision makers, it is also important to understand that a focus on key rituals, habits, and routines can explain a lot of what goes on in organizations on a day-to-day basis. This is also a powerful way to view culture for those who are trying to change organizations.2 As psychologist William James noted many years ago, habit is the “flywheel” of society: “We must make automatic and habitual … as many useful actions as we can. The more of the details of our daily life we can hand over to the effortless custody of automation, the more our higher powers of mind will be set free for their proper work.”3

When trying to lead culture change, it is always useful to view organizations as a bundle of interdependent rituals, habits, and routines. These routines capture knowledge and translate it into action in an efficient way that conserves energy and resources. The good news is that we don't have to think through everything that we do every time that we do it! But this also means that much of the essential logic of any organizational system tends to sink to an unconscious level, hidden from public view. This all tends to work fine until that moment when the world starts to change around us, and then we have to go through the difficult—and often expensive—process of rethinking what we do, how it fits together with the rest of the organization's capabilities, and how that creates value for the customers.

One of the best stories of innovation ever told is historian Elting Morrison's tale of the evolution of naval artillery, Gunfire at Sea.4 Before the invention of continuous aim firing, cannons were solidly mounted to the side of a battleship. That made it very hard to aim! Continuous aim firing created a system in which the cannon moved back and forth with the motion of the waves so that a gunner could keep his aim on the target. The result? A 6,000-percent increase in accuracy. To understand the magnitude of this innovation, consider Morrison's account:

In 1899 five ships of the North Atlantic Squadron fired five minutes each at a lightship hulk at the conventional range of 1600 yards. After twenty-five minutes of banging away, two hits had been made on the sails of the elderly vessel. Six years later one naval gunner made fifteen hits in one minute at a target 75 by 25 feet at the same range—1600 yards; half of them hit in a bull's eye 50 inches square. [p. 19]

So how long do you think it took for this unbelievable 6,000-percent improvement in accuracy to be translated into action and spread throughout the fleet? The real lesson from Morrison's story is that it took over a generation for this innovation to actually be adopted. Old habits die hard, and sometimes they die only with the people who hold them.

Morrison's essay opens with the story of a young time-and-motion expert trying to find a way to speed up artillery crews during World War I, just after the fall of France. He watched one of the five-man gun crews practicing in the field with their guns mounted on trailers, towed behind their trucks. Puzzled by certain aspects of their procedures, he took some slow-motion pictures of the soldiers performing the loading, aiming, and firing routines.

When he ran these pictures over once or twice, he noticed something that appeared odd to him. A moment before the firing, two members of the gun crew ceased all activity and came to attention for a three-second interval extending throughout the discharge of the gun. [p. 20]

Since this seemed like quite a waste of time, and the young time-and-motion expert really couldn't make any sense of it, he asked an old artillery colonel to look at the films to see if he could explain this strange behavior.

The colonel, too, was puzzled. He asked to see the pictures again. “Ah,” he said when the performance was over, “I have it. They are holding the horses.” [p. 20]

A generation earlier, when the colonel fought in the Boer Wars in South Africa, it was important to “hold the horses.” With horse-drawn artillery, if you didn't hold the horses, they would bolt, dragging the guns along with them. Bad scene. But now, with guns mounted on trailers that were towed by trucks, there was no more need to hold the horses. Nonetheless, the old habits die hard and the vestiges of the past tend to linger on, long after they have outlived their usefulness. The habits that were once an ingenious part of making a complex routine work effectively had become the “ritual inclusion of structure, that no longer serves any purpose.”5

Habit is, to paraphrase Deepak Chopra, a frozen interpretation of the past that is used to plan the future.6 An old Chinese proverb states that habits are “cobwebs at first, cables at last.”7 Warren Buffett described exactly the same dynamic when he said, “Bad habits are like chains that are too light to feel until they are too heavy to carry.”8 By the time we realize how restrictive our old habits have become, it is often too late to do very much about them.

Habits and routines are also difficult to change because they are so tightly interlinked. They fit together in complex chains of events that define “the way we do things around here.” The cross-cultural classic Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands shows how the most difficult aspect of executing routines correctly is that they require a shared mindset among multiple participants9. If you are trying to bow and the other party is trying to kiss, it really doesn't work very well. Changing only our own part of the equation seldom works, because all of the others are still linked together in the same way as before.

Suppose that an ambitious young chef decides to change the menu in his restaurant. Lots of other things must also change to support that decision: buying produce, training sous chefs, advertising, and explaining the new menu to waiters and waitresses all must change at the same time in a complementary fashion. A restaurant that we go to recently decided to change its menu to appeal more to “locavores”—those who favor eating foods that are locally grown. This not only makes a dramatic difference in how and where the restaurant buys its produce but also has a far more radical impact: The menu has to change continually in response to what is available, season by season, in the local region. As in many industrial companies, production, distribution, and the supply chain all have to change in a complementary way for the system to remain in harmony.

A Framework for Leading Culture Change

When talking about culture change, some authors have emphasized the importance of changing values,10 whereas others have concentrated on the dynamics of the change process.11 Still others advocate changing the business first and then making sure that the changes stick by institutionalizing the new way of working.12 Others have worked hard to link the adaptation process to the mindset and underlying assumptions of the leaders.13 All of these approaches are an essential part of any leader's toolkit and represent significant points of leverage that can be used to lead culture change.

But in our experience, making culture change stick requires digging a bit deeper into an organization's basic habits and routines. Routines link the abstract and concrete levels of culture in real time, and using that frame of reference for cultural transformation brings a vague cloud of opportunity down to earth in a rainstorm of practical action. Nonetheless, this emphasis on rituals, habits, and routines has received much less attention than the values and beliefs perspective, so we think that it is important to describe it here in some detail, as a way to summarize what we have learned from the research presented in this book.

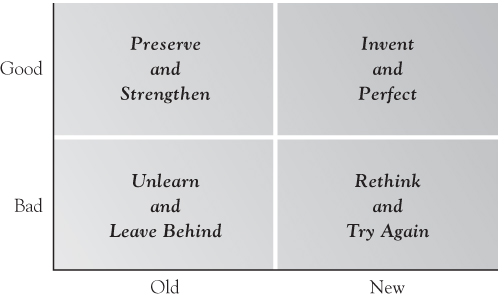

To organize this, we have developed a simple framework to categorize rituals, habits, and routines that has been helpful to many organizations as they discuss their approach to transforming their cultures. One dimension of the framework contrasts the old with the new. Are the routines well grounded in the past traditions of the organization? Or are they newly constructed routines that have just recently been put in place? The other dimension of the framework is good versus bad. Are the routines effective or ineffective? Are they creating value? Or are they just the vestiges of the past that have outlived their usefulness? These four categories suggest four different types of action, as shown in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1 Changing Culture by Changing Rituals, Habits, and Routines

Bad Old Habits: Time to Unlearn and Leave Behind!

One of the strongest motivations for changing a culture is the dilemma posed by the set of bad old habits that have been around for years and have long outlived their usefulness. It can be hard to unlearn these well-established habits and leave them behind, but that's exactly what needs to happen. Let's consider three examples from the companies in this book.

The Old HR Process at Domino's

At the beginning of its transformation, Domino's had over a 150-percent annual turnover of people. The system of policies, practices, processes, and routines that created this situation had built up over the years as a reflection of a culture in which management almost always spent more time discussing the price of cheese than they did discussing the talent of their people. Their habits were very well-established. Individual store owners could do pretty much what they wanted, and typically they saw little connection between the quality of their people and the performance of their store. Corporate HQ generally kept their distance on this issue and at best offered guidelines for franchisees, rather than mandates for best practice. At the corporate level, there was also relatively little strategic HR planning or focus on capability development. Individual leaders came and went as they gained power or fell from favor. Little attention was paid to their development as leaders or to succession planning. All of these habits were well ingrained and had been in place for years.

The HR process was an easy target for improvement. It became very apparent, almost immediately, that this process was old and bad—and furthermore, that it clashed quite dramatically with the new CEO's values and approach to managing the organization. So it quickly popped up to the top of the chart of things to change, starting now. Once a leadership team or group of employees reaches consensus on a set of bad old habits to unlearn and leave behind, this helps to build dissatisfaction with the status quo and focus attention on alternatives for the future. This is one of the key strengths of identifying some of an organization's worst habits as a part of a target for change. It creates one more burning platform to help build momentum.

The Sales Process at DeutscheTech

In the year or two after merging adhesives, sealants, and surface treatments together into one business, DeutscheTech would still send two or three different salespeople out to visit customers representing these three different technology areas. They would compete for time on their customers' busy schedules. This set of habits not only created the impression that DeutscheTech was a collection of small vendors rather than one large vendor, but also created a barrier to the potential areas of collaboration between the related technology groups. The idea that the three different technologies could be combined in ways that would better address a customer's needs was at the core of the decision to merge the units. But in practice, it was very difficult to do until the sales process was integrated in a way that could actually deliver the integrated value to the customer. It was a classic example of how a decision to merge two units together may make perfect sense strategically but not be very visible to customers, because the habits and routines of the market-facing parts of the organization haven't yet been realigned with the strategy.

Both learning and unlearning were required to make this change stick. Individual salespeople needed to take a big step forward to learn how to actually sell the entire range of products in the newly combined adhesives business. On bigger projects, engineers also needed to unlearn the idea that they were the technical experts, able to answer all of the questions. They needed to learn to deliver as a team, in which they were the experts on the customer's needs, rather than about any specific part of the DeutscheTech technology. This example shows us one of the reasons that culture often takes so long to change. The culture reflects the logic by which knowledge gets translated into action. New knowledge, new people, new processes are all required to unlearn the bad old habits and leave them behind.

Fiefdoms at Vale

When Vale was first privatized, they had to confront the fact that the company was organized around individual mines. Traditionally, there was not much systematic structure standing between the mines and the government bureaucracy. Plus, the mines were generally a long way from the headquarters in Rio. Because of that, the individual mines tended to be fiefdoms controlled by individual leaders. Finance, purchasing, logistics, accounting, human resources, and operations were all organized differently at each mine, with very little attention given to the operations of the corporation as a whole. They each had their own habits and routines, with little accountability. Little attention was paid to standardizing mine operations or coordinating capabilities among the mines.

The first steps in the process of creating “one Vale” focused on exactly this problem. Defining a new set of standardized business practices and processes to be adopted across the organization became the main thrust for getting the Brazilian business in order before taking the next steps toward globalization. At first this was unpopular and often viewed as disruptive. It generated a lot of resistance, even though it was absolutely essential if Vale were to move forward.

Every organization has a long list of bad old habits that they are trying to change. But just complaining about the bad habits and hoping that they will change is not nearly enough.14 A clear focus on the areas of consensus about these targets for change can help to build progress and momentum and help develop the experience and conviction to take on bigger challenges.

Good Old Habits: Time to Preserve and Strengthen!

Sometimes, when organizations are undergoing widespread change, they can lose sight of some of the strengths that have made them great and end up “throwing the baby out with the bathwater.” But some of the old and well-established habits and routines from an organization's past are still essential to the organization's success in the future. They are well understood by the people, they are a key part of the organization's mindset, and they are closely linked to other aspects of the organization's functioning. Therefore it is very important to clarify the core habits and routines that need to be preserved and strengthened. Here are three examples to help illustrate the importance of seeing the good old habits clearly.

Domino's Franchise Agreements: The OBI Clause

As we noted in Chapter Two, Domino's required all of their franchisees to sign an agreement that limited the franchisee's ability to maintain “outside business interests.” This meant that all Domino's franchisees were completely focused on their pizza store. This legal requirement created a situation for each Domino's franchisee that was much like the situation for the first Domino's store, opened by founder Tom Monaghan and his brother Jim. Failure was not an option. And when success comes to that first store, what happens next? You open a second store! And then a third, and a fourth, and so on. This requirement created a singular focus that has helped build commitment throughout the Domino's system. Domino's choice to preserve and strengthen many of the time-tested practices and routines at the store level was an important part of their change strategy.

The OBI-related habits and routines also created some limitations for Domino's, especially as they expanded globally. It was impossible to maintain this focus as they developed relationships with master franchisees throughout the world, and they have sometimes had difficulties dealing with franchisees who had other options and interests. But overall, this principle was a tremendous strength that was preserved and strengthened as the Domino's transformation unfolded.

Polar Bank: Maintaining a Local Presence

One of the biggest challenges faced by Polar Bank was how to build a transnational European organization that could leverage the capabilities of their three different banking businesses across national boundaries. It was tempting, in that situation, to try to reallocate resources and attention away from the local businesses to help integrate the banks. But this was a risk that Polar Bank was reluctant to take. They saw that the strong local presence of the consumer banking business in Norway, the public finance business in Sweden, and the investment banking operations in Denmark was the foundation of the bank's future success, and they were reluctant to compromise that in any way.

The new capability of cross-border integration was a capability that needed to be built on the platform of a strong local presence in a way that did not compromise that strength. Thus it is a good example of choosing to preserve and strengthen a key orientation from the past, even as the bank built a new platform for the future.

GE Healthcare: Entrepreneurial Focus on the Value Segment

When GE Healthcare acquired Zymed in 2006 (and renamed it CSW), they instantly gained a strong position in the value-segment anesthesia business in China. Zymed posed several challenges for GE, but they also offered something unique—a Chinese-style family business with a strong sales focus and an entrepreneurial culture. They were thrifty, they executed extremely well, and they had a relentless and dynamic sales process. They also had deep roots in the Chinese market and its health care systems and needs.

But many of the entrepreneurial characteristics of Zymed presented challenges, because they were quite difficult to combine with the other two components of the organization, the higher-end Datex-Ohmeda anesthesia technology, and the process discipline of the GE global anesthesia business. But the D-O and GE perspectives brought little to the table in terms of tacit knowledge of the local market and the fast-moving, sales-oriented habits needed to capture market share in the dynamic Chinese market. As a consequence, GE redefined nearly every routine in the organization, and at each stage they had to weigh how they could apply the enormous technology and process expertise of D-O and GE, while still retaining the dynamic spirit of Zymed.

When the pace of change picks up, it can be easy to forget to protect those elements of the culture that made the organization great. If these factors aren't consciously protected from the beginning, they often disappear before you know it. And it is a lot harder to create them again the second time around.

Good New Habits: Time to Invent and Perfect!

Perhaps the most exciting part of the culture change process is the opportunity to create something new. Creating new routines to leverage new ideas in a new way can be the most exciting part of all. The canvas is not exactly blank, because the new routines must be well integrated with the other parts of the organization that do not change, but it is nonetheless a great opportunity to create something new. Again, we look at three examples of how some good new habits were created by our case study organizations.

Swiss Re Americas Division: Creating a New Operating Model

To implement a change from an old top-line strategy to a new bottom-line strategy, Swiss Re changed their operating model. What they really changed was the process by which they made decisions about their response to customer opportunities. Before the transformation, the client representative ruled. They would represent the client opportunity to the organization and work with the actuaries and underwriters internally to get a solution that would work for the client. They were less concerned about the profitability of the individual deal—and more concerned about growing top-line revenue.

The new operating model changed all that. Decisions about booking new business required a consensus among the client representative, the actuary, and the underwriter. It is a classic example of how a strategic change requires a change in a basic work routine and has a broad, practical impact on nearly everyone in an organization.

The Swiss Re case is also an interesting lesson in how important it is to find the pulse of an organization when you are trying to create a transformation. Their change to the new operating model took place during one of the busiest times of the year: the fall renewal season, when the organization was renewing contracts for the coming year. That's the heartbeat of the organization. During the busiest time of the year, they implemented the new operating model one week at a time, debriefing, learning, and strengthening as they went. At the end of that renewal cycle, they had implemented the new routine, implemented the new strategy, and created a new mindset among their people that supported this transformation.

Polar Bank: Creating a New System of Governance

To integrate three different banks in three different banking sectors in three different countries, Polar Bank chose to create one board that would govern all three banks. This bold change in the governance of the three banks created a totally new dynamic. Coordination started at the top, and the framework was set for cross-border learning. Standardization on the back office side, lessons about cross-border and cross-business marketing, and common approaches to managing risk and access to capital were all pursued by the same team, in the three different contexts. The creation of one board forced a level of integration that could have taken years to achieve if they had tried to achieve it at a lower level in the organization. The new board also combined the expertise in the three different banking sectors in a way that none of the individual banks could ever have done, creating a shared mindset that was the foundation for a full-service bank.

Polar Bank also invested quite a bit in a new system of leadership, whereby the leaders in each of the three banks were expected to develop expertise, understanding, and respect for all three of the banks, even though their specific job responsibilities were still squarely within one of the banking sectors. Some of them saw it as a waste of time, or an academic exercise that was “nice to have.” But others realized that any follow-up to the governance changes at the top depended on a cadre of leaders that were aligned with the new mindset that was taking shape at the top.

GE Healthcare China: A Vision-Led Integration

It was a bold step forward for Matti Lehtonen to decide that the integration of the strengths of Zymed, Datex-Ohmeda, and GE Clinical Systems Wuxi should be a “vision-led” integration. Why not process-led? Why not technology-led? Why not market-led? The choice of leading with vision raised a lot of questions at the time, but it did serve the purpose of defining a future state that built on the aspirations of each of the parts of the organization and that served as a platform for defining a common future working together. Once this common future vision was understood, that created a foundation for starting to integrate the three different parts of the organization.

Leading the process by defining a future vision had the interesting effect of creating a widespread consensus that new processes, routines, and habits would be created in almost every part of the organization, before actually defining what those processes were going to be. Most important, that allowed people to focus on the future that bound them together, rather than the diverse processes, values, and routines that could drive them apart. The discussion of “Whose process should we choose?” and “Which one of the three is right?” was deferred until everyone understood both the big picture and the strategic rationale behind the new organization.

Creating new rituals, habits, and routines is difficult. There are several pieces to the puzzle: Mindset, behavior, and systems must all change together to reinforce the adaptation process for the organization. As leaders, we can't just open up people's heads and rewire their brains, or prescribe a new set of behaviors that must be followed, or mandate a new system. We can't just grab one of those levers and start pulling. Instead, we need to gently but persistently push harder and harder on all three of those levers at once, until we see some of the signs of success that will encourage others to join in to help build the momentum.

Bad New Habits: Time to Rethink and Try Again!

Perhaps the most curious category of the four categories of habits and routines is the bad new habits that are sometimes created during culture change. Creating a new set of habits and routines doesn't always mean that they are going to work the way that they were intended the first time and that they will fit the situation well. On the contrary, culture change requires a lot of trial and error. In fact, the existing culture in every organization is made up of years of experimentation to find out what works the best and how that knowledge should be institutionalized. Thus these three examples drawn from our case studies point to situations in which the first attempt to create a new routine did not exactly hit the bull's-eye, but instead required some midcourse correction in order to get the job done.

Vale: The Centralized Approach to Integrating the Inco Acquisition

When Vale acquired the Canadian nickel producer Inco, it was the largest acquisition that had ever taken place in either Brazil or Canada. Vale's centralized approach to integration didn't give them the results that they wanted, so they were forced to rethink their approach and try again. Several expatriate assignments that sent Brazilians to Canada or sent Canadians to Rio didn't work out very well, and they were forced to try again. It took time to develop the alignment and control to be able to run this business effectively from headquarters.

Vale was quite adept at recognizing that they had missed the target and stepping back to refocus and try again. On the second round they were much more successful, both at running Inco on the ground in Canada and at representing Inco's interests well at the corporate level. It was their first experience at integrating a major acquisition, so the lessons of the initial phases of their integration process drove a rapid learning curve. With this experience, they did much better on their second attempt.

GT Automotive: Applying Service Learning Methods in the European Transformation

GT Automotive is an interesting example of how a culture change that was successful in one part of the world, North America, was extended to another part of the world, Europe. The interesting part is that most of the tactics employed to roll out this change process in North America were used as the foundation for the change process in Europe. There were some differences from one country to another, and certainly there was a different feel in the involvement meetings that took place in Italy from the ones that took place in Germany. But to our surprise, most of the process transferred quite well, with one exception: service learning.

Service learning involves organizational members in volunteer work or charity work in their communities. It has been used in many different settings to build a bond and a commitment within the team as they devote their time and effort to a community cause such as delivering meals, working at a homeless shelter, or helping underprivileged children. These efforts also show to themselves and to others that they are concerned with creating value beyond just increasing the profitability of their business. In North America, this was an important component of the change process in each of the locations. But in Europe, they discovered that this didn't have the same effect. So this key part of the change process was modified, on the fly, to maintain the momentum of the transformation.

GE: Improving Product Quality

Product quality with anesthesia equipment is serious business. When GE acquired Zymed, they experienced many quality problems. At one point, they even stopped production on the Zymed line until they were certain that they would be able to deliver high-quality machines that lived up to the GE reputation. Their attempt to resolve these problems required them to use a series of processes, each of which required a different set of routines and changes in mindset. At first, they simply needed to find and fix the quality problems as they arose. When customers had a complaint, GE engineers in Wuxi would try to trace the model number back to the drawings that they had acquired from Zymed. But many times, those drawings weren't very accurate, or simply weren't available. Solving problems using this routine was very time-consuming and not very successful. Worse yet, it also took the engineering resources away from the product development process that would create the next generation of products.

To respond to quality problems, they had to get extremely good at find-and-fix routines. But to ensure that they had less to find and fix in the next production series, they also needed to introduce another new set of routines, borrowed from GE's legendary production process knowledge. They had difficulty adopting GE processes in total because, at least at first, they were unable to work to such a high standard. But they made steady progress in improving production quality and gradually created fewer find-and-fix problems for themselves.

But the third stage of evolution required them to improve their product quality by redesigning the product to eliminate even more of the quality concerns. This presented yet another set of routines to the GE engineering team. But even this redesign could not bring their quality to a level where they could seek FDA approval. That would come next, and it would present the team at Wuxi with the next set of challenging routines to master.

The culture of every organization represents the accumulated wisdom of years of experimentation. What works, sticks. What doesn't, doesn't. Just because an organization decides that it is going to change anew doesn't mean that it will get everything right the first time. Enlightened trial-and-error is especially important as we try to create the new rituals, habits, and routines that will transform an organization's culture.

Understanding the Importance of Routines

Think for a moment about all of the steps required to create that shiny new smartphone in your purse or pocket. Millions of separate events are integrated around the globe through a complex supply chain and a nearly endless set of business processes for design, production, and distribution. The human habits and routines that complement this highly technical process always reflect the core logic of how the organization operates. So it is important to see the close links between the mindset of the people, the systems that they have created, and their ability to survive in a competitive business world.

Routines and habits link knowledge to action. When we are trying to lead a cultural transformation, we have to rethink that connection. Connecting the visionary with the practical, the abstract with the concrete, and the principles with the practices is always at the core of any culture change.

Tracking Our Progress

Each of the case studies in this book was informed by an assessment of the culture of the organization at the beginning and the end of the story. The stories give us the clearest picture of what happened in each organization. But because it is sometimes hard to generalize about stories, the assessment was a useful way to track the cultural transformation. It also helped us pick a set of stories in which the positive changes in the survey results indicated that the organization was moving in the right direction. What's more, the assessment often informed the transformation process by forcing the organization to take a look in the mirror and understand their strengths and weaknesses more clearly. Of course, some parts of the culture can be accurately measured and tracked, whereas others cannot. Or, as Einstein had posted on his office wall at Princeton, “Not everything that counts can be counted, and not everything that can be counted, counts.”

In addition to giving us a means to track the transformation process, the survey was also an intervention in its own right, designed to help drive the transformation. The results gave the members of the organization a good look at themselves. It was not always a pleasant experience. One president said, “It was like you told me that my baby was ugly. And smelled bad!” The results helped focus everyone's attention on the challenges that they faced. Groups, teams, departments, and divisions throughout these companies looked at the results and used them to plan how to improve.

Our role in these stories varied a lot. As we noted in each chapter, sometimes we were actively involved in planning and process consultation,15 and in other cases we were teachers or organizational development consultants. We were connected with all of these organizations for at least two to three years, and we have worked with several of them for nearly a decade. Our involvement had a positive impact on all of these organizations, and we are proud of that.

But the most powerful catalysts for change in all of these organizations were the leaders themselves. The essential ingredient was always their insight, their vision, and their conviction that the time for change was now. They also had a lot of staying power. None of these organizations changed by making culture the flavor of the month. We learned a lot from them. This book is a way to share those important lessons with a broader audience, so that we don't all have to make all of these mistakes for ourselves.

Building for the Future

For nearly two decades, the top leaders of Japanese camera and copier giant Canon met each day at 7:00 a.m. for their Asakai morning meeting over tea. They typically spent about an hour together. There was no formal agenda. They talked about what they thought was important to talk about together. They talked about the principles and philosophies that they thought were most important for running their business. They talked about what was working and what was not. They talked about their people, their competitors, their products, and their technology. They listened a lot to their legendary leader, Fujio Mitarai, talk about the unique, evolving philosophy that had guided Canon through the years. But most of all, they talked about how it all fit together and what they wanted to create for the future at Canon. Their remarkable achievements stand clearly for all to see.

Very few organizations would ever take so much time at the top to ensure the alignment and integration of the leaders and their perspectives. But all global organizations that want to present one brand, one value proposition, one integrated set of products and services, and one team of talented and motivated individuals who are dedicated to their success need to find their own way of creating integrity. Different cultures and different industries may each have their own approach. Organizations old or new, large or small, may also have unique strengths that they can draw on. But in the end, to survive for the present and build for the future, leaders need to create a unique culture and mindset of their own, to differentiate themselves from the competition and gain the commitment and dedication of their people.

Notes

1 Schein, Edgar H. Organizational Culture and Leadership (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2004.

2 Cohen, Michael D., and Bacdayan, Paul. “Organizational Routines Are Stored as Procedural Memory: Evidence from a Laboratory Study.” Organization Science 5, no. 4 (1994): 554–568; Cohen, Michael D. “Reading Dewey: Reflections on the Study of Routine.” Organization Studies 28, no. 28 (2007): 773–786.

3 James, William. The Principles of Psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1890.

4 Morrison, Elting E. Men, Machines, and Modern Times. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1966, 17–44.

5 Feynman, Richard. Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! (Adventures of a Curious Character). New York: Norton, 1985, 340.

6 Chopra's original quote is “A habit is a frozen interpretation from the past that is applied to the present.” http://davesdailyquotes.com/?p=7594

7 See Stone, John R. The Routledge Book of World Proverbs. New York: Routledge, 2006, 199.

8 Clark, David. The Tao of Warren Buffett: Warren Buffett's Words of Wisdom: Quotations and Interpretations to Help Guide You to Billionaire Wealth and Enlightened Business Management. New York: Scribner, 2006, p. 16.

9 Conaway, Wayne A. Kiss, Bow, or Shake Hands. Avon, MA: F+W Media, 2006.

10 Lencioni, Patrick M. “Make Your Values Mean Something.” Harvard Business Review, July 2002, 5.

11 Collins, Jim. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don't. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

12 Kotter, John P. Leading Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1996.

13 Schein, Edgar H. The Corporate Culture Survival Guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

14 Weeks, John. Unpopular Culture: The Ritual of Complaint in a British Bank. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

15 Schein, Edgar H. Process Consultation: Its Role in Organization Development, vol. 1. Boston: Addison-Wesley, 1969.