Chapter 4

Creating One Culture Out of Many

One Shell. One EMC. One Metso. One Merck. One Deloitte. One IBM. Nearly all of the companies that we work with today are trying hard to integrate the disparate parts of their far-flung global empires into one coherent whole. “Enterprise thinking” refers to the mindset that allows people to act on behalf of the organization as a whole, rather than representing just one part of it. Even when companies grow organically, it is often harder than it looks. Consider this story: after a round of golf, legendary GE CEO Jack Welch allegedly asked equally legendary Canon CEO Fujio Mitarai if it was possible to get one global price and service agreement for Canon copiers for GE worldwide. Mitarai-san confirmed that they could do it. But when Mitarai went back to his organization, he heard a different story. Because of the structure of Canon's highly successful regional sales companies in the United States and Europe, it took a lot of extra work to negotiate one global price and one service agreement. Global integration is a big challenge.1

But when companies grow through acquisition, the challenge is even greater. When Hewlett-Packard acquired IT solutions provider EDS, the combination was irresistible. H-P sold products. EDS sold services. The merger offered them both a way to compete more directly with the giant in their industry, IBM Global Services. But achieving the high-quality integration necessary to fulfill the promise takes a lot of time and effort. When Canon acquired the Dutch printing and solutions company Océ in 2009, the stakes were even higher. Not only did they need to integrate products and solutions such as HP and EDS, but they also needed to do so across national boundaries. Canon was Japanese, Océ was Dutch, and the Americas were a big competitive market, where the integration needed to go smoothly in order to make the acquisition a success.

E Pluribus Unum

Mergers pose the greatest integration challenges when multiple aspects of the corporate identities involved are stacked up against one another. Cross-border mergers, when integration spans national borders, can be very difficult.2 But mergers that span business sectors, like HP-EDS, and require the integration of products and services also present a lot of complications. What about the customers? Daimler-Chrysler failed for many reasons, but the differences between the automotive industry's premium segment and the mass-market segment certainly added to the challenge. When mergers throw in a new combination of technologies, new ownership and governance structures, and a different leadership style and history, then the Holy Grail of synergy becomes harder and harder to attain. In the words of one M&A veteran: “Buying is fun; merging is hell.”3

Difficulty in aligning these deep-rooted cultural differences is one of the main reasons that many mergers are unable to deliver on their promise.4 Corporate cultures are built up of all of the interlocking habits and routines that make up an organization's formula for success. But evolving beyond their past success requires an organization to rethink the past and unlearn those practices and principles that need to stay in the past and to reinvent the new organization that will lead them into the future. Their future success depends on the quality of this process.

This chapter examines these issues by focusing on the efforts of the Scandinavian financial services firm Polar Bank as they struggled to integrate three strong cultures into one company.5 For several years after the initial acquisition there was little progress. But then a new CEO, Katarina Hansen, started to focus on the whole company—rather than the individual banks—and tried to move the organization from the point of talking about integration to the point of doing something about it.

History Has Its Own Logic

Polar Bank grew out of the 1996 merger between the Norwegian retail bank Fylkesbanken and Sweden's Ländesbanken, a leader in pubic financing. Fylkesbanken also held a controlling interest in Denmark's oldest private bank, the International Bank of Denmark (IBD), with Ländesbanken as a minority partner. IBD was focused on asset management. So, three different corporate entities, three different countries, three different traditions, and three different sectors of the financial services industry. The vision for this combination was compelling: They wanted to create the leading Scandinavian full-service bank with strengths in retail, public financing, and asset management.

But for several years after the merger, these three different banks continued to operate quite independently; each bank focused on its home country. The companies had very different organizational cultures. Fylkesbanken's strength was in their local retail presence throughout Norway. Basically they operated as a national federation of small-town retail bankers. Ländesbanken also had a strong local presence throughout their home country of Sweden, but their strength was in serving the public financing needs of Swedish municipalities, a very different segment of financial services. In addition, several smaller organizations that were acquired since the 1996 merger—such as the Norwegian insurance company that they bought in 2002 or the Finnish retail bank that they had acquired in 2004—had also remained independent. Each bank's executives were totally focused on their own local performance and were not very concerned about Polar Bank as a whole. After all, why should asset managers in one country be concerned about how retail bankers in another country did their jobs?

Tracking the Transformation

When Katarina Hansen was promoted to CEO of Polar Bank in January 2005, she quickly concluded that the future of Polar Bank was limited as long as the bank remained a collection of unintegrated acquisitions. She felt that they would be vulnerable to acquisition and would never achieve a dominant position in the Scandinavian market if they weren't well integrated. Hansen had been associated with the bank since the 1996 merger, first as their outside counsel, then as a board member, and for the prior four years as the head of their office of general counsel. Her affiliation with the corporate center rather than one of the individual banks was viewed as an important strength for her new role as CEO. But the results from our Culture Survey showed that she had her work cut out for her.

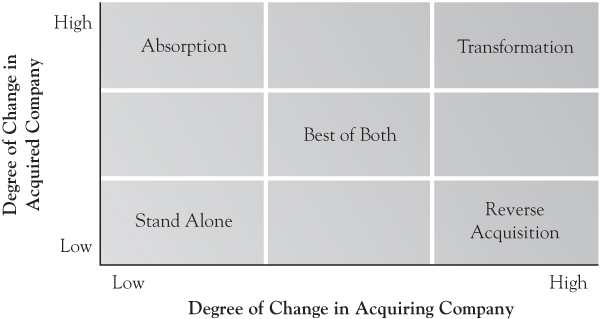

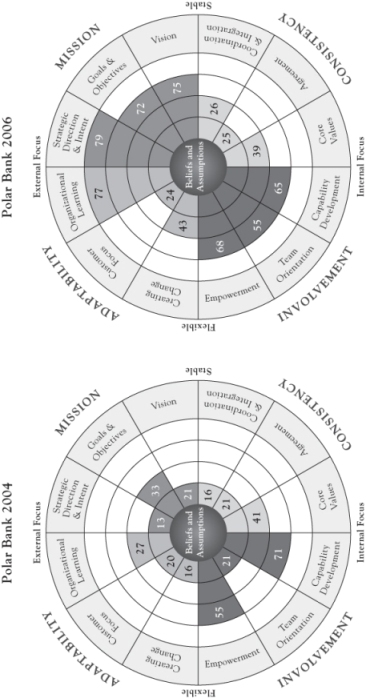

The survey results showed that Polar Bank's strategy and vision were not clear (see Figure 4.1). These also showed that they lacked coordination and integration across business lines and borders. They had not built one team and hadn't created a consensus to move toward one overarching culture. Nor were they very focused on customer satisfaction. But despite this lack of attention to the creation of a single culture, Polar Bank still showed many signs of being a good employer, with notable strengths in capability development and in the empowerment of their people in the corporate center as well as in each of the banks. The survey results from the three banks had a lot of similarities, although the results for Ländesbanken in Sweden were stronger than for the other two banks.

Figure 4.1 2004 Culture Survey Results: Polar Bank

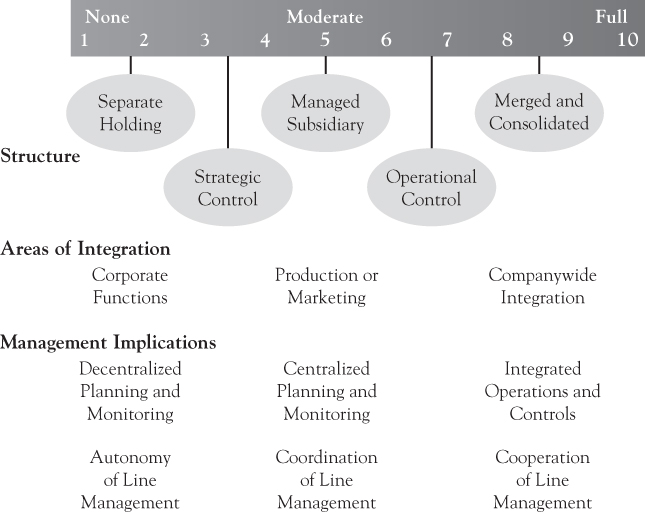

Figure 4.2 shows the highs and lows from the sixty-item survey. This figure presents the five highest items in the survey and contrasts them with the five lowest. This contrast shows that the main strengths of Polar Bank are mostly in the area of involvement. The main challenges, in contrast, are in the areas of innovation, risk taking, coordination, and vision.

Figure 4.2 Polar Bank 2004 Culture Survey: High and Low Scores

To Hansen, these survey results signaled that it was time to start addressing the problems and recognizing that Polar Bank was still made up of three different cultures. She totally agreed with the previous CEO's vision that the bank should operate as one company. But even though the previous CEO had talked a lot about operating as one company since the 1996 merger, few changes had actually occurred. Polar Bank's structures and processes remained mostly unchanged, and the top team was not truly engaged in the integration process. They met every two weeks, but usually just went back home and ran the banks the same way that they always had. Hansen knew she had to transform the bank quickly if her vision was to become a reality. Based on the survey results, she decided to focus on the strategy process, the governance structure, and the development of their top leaders.

Developing One Strategy

Trying to lead one organization with three separate strategies hadn't worked very well. But developing one strategy would require the executives and managers to build a much greater understanding of each other's businesses and strategies. To start this process, Hansen organized a series of strategy workshops with managers from all levels of the three banks to join in an open discussion on the strategy of each business unit. Integrating three banks with three different strategies required a big investment of time and effort. Only if they understood the other banks' current strategies could they understand what they could accomplish if they worked together.

The managers generally agreed with the basic approach of building the bank around business lines that spanned national boundaries. But there was no consensus on how to do this. To succeed, Hansen realized, she would need deep involvement from many levels of the organization and therefore created a combined cross-business and bottom-up approach to strategy development. This meant that the senior managers from the retail bank in Norway needed to understand and buy into the strategy for the public finance bank in Sweden and vice versa. These multidepartmental strategy discussions sent a strong signal to all of the groups that Hansen was serious about developing one overarching strategy and culture for Polar Bank. In addition to senior managers, she also involved a large group of high potentials in the strategy process. By June 2005, this process had helped to clarify and communicate the strategic vision: Polar Bank clearly aspired to be the major player in retail banking in Scandinavia and to be a European leader in public finance and asset management.

Communicating One Message

Communicating her message about the strategic vision to all stakeholders was also important. Hansen's message was that better integration was essential to Polar Bank remaining independent. Without better cross-border and cross-business integration, Polar Bank was likely to be acquired by a competitor as part of the ongoing industry consolidation in Europe. Hansen's message was that the banks that were the best at integrating their acquisitions would be the most likely to survive the consolidation of the industry.

She started with her top team. She argued that they needed to get passionate about the integration, even though passion was not always a top priority among her bankers. She walked a fine line, stressing that Polar Bank was “not desperate to find a partner before it is too late,” but that they had to be stronger if they were going to be able to continue operating as a stand-alone company.

This message had to be communicated both internally and externally. Hansen organized meetings in the three different entities at the same time as a June 2005 meeting with financial analysts to discuss Polar Bank's new strategy. While she was in Norway with the analysts, members of the group management board were present at the Swedish and Danish locations and delivered the same presentation. This new approach to communication was a clear break with the past, when all communication was focused on the issues facing the individual banks. Shortly after the announcement of the strategy, Polar Bank also acquired a Finnish retail bank. This showed both the employees and other stakeholders that Polar Bank was serious about its strategy and that it would allocate its resources in ways to support their ambitions.

Creating One Corporate Center

Since the 1996 merger, the corporate headquarters of Polar Bank had acted more like a holding company than a strong corporate center—only corporate finance had any real influence. The corporate center did not have an overall strategic plan or a set of staff departments such as human resources, information technology, or back-office operations. As in a holding company, each bank was focused on maximizing its own profits rather than creating synergies and maximizing the profits of the Polar Bank group as a whole. In order to move forward, they created stronger human resources, finance, marketing, and branding in the corporate center. They also made an effort to spread best practices across the different banks. Finally, Polar Bank ensured that the best people had opportunities throughout the organization rather than in the bank in which they were based.

Creating One Board

Hansen took another step forward by restructuring the management boards of each of the three entities. Each bank's board now included the CEO of all three banks, Hansen, and three other members of the group management board. This new arrangement reinforced the idea that each bank's CEO had to operate with a group mindset. More than any other single step, this move gave a strong and decisive signal that Hansen was serious about creating a bank that operated as a single entity and not as three separate ones.

Creating One Team

Hansen also realized that she must have people who believed passionately in the vision. She worked to ensure that the right people were in the right positions. One key human resource executive, for example, did not openly reject Hansen's approaches, but did give a lot of passive resistance. Some key strategies—such as 360-degree feedback and coaching for top management, and using the corporate university to develop executives from all three banks and the corporate center—received only lukewarm support from this executive. People quickly noticed, and it made them wonder how serious Hansen was about the making the changes. So she asked him and several other capable but slow-moving executives to leave.

Creating One Leadership Development Process

Hansen knew that she had to align all of Polar Bank's systems and structures to support her efforts to change the culture. The Polar Bank corporate university developed a leadership program in which senior executives from all of the banks worked on their leadership skills. Teams of managers focused on five key leadership dimensions: customer orientation, vision, innovation, people management, and cross-boundary collaboration. Each team had a board member sponsor, and six weeks after the program, they presented the management board with their ideas, some of which they adopted on the spot.

Hansen and the management board also led the way in the widespread use of 360-degree feedback and coaching. Actions speak louder than words. Since then, over four hundred top leaders have taken part in this feedback and coaching process. The corporate university created a program to rotate young, high-potential managers around the three banks for six-month assignments. This was another instrumental step in breaking down Polar Bank's silo mentality, promoting managers' understanding of its different subcultures, and creating a pool of mobile international managers. Polar Bank also implemented talent reviews to help identify and manage talent across boundaries.

Tracking the Transformation

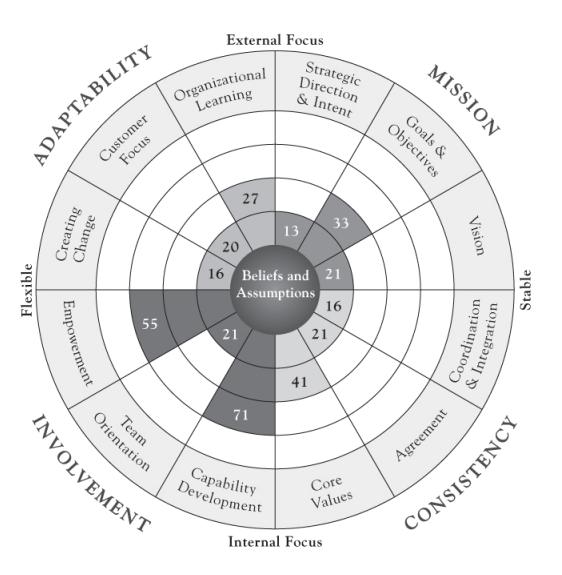

The changes that Hansen and her team had put into place slowly started to have an effect. In September 2006, about eighteen months after she took over as CEO, she decided to repeat Polar Bank's Culture Survey to assess the progress that they had made. As is the case for many organizations, she saw major improvements in the areas where they had put the most attention. All elements of mission improved dramatically: Strategy and vision increased by over fifty points each, and the clarity of goals and objectives also grew dramatically. All of the work that they had done to clarify the direction of the bank for the future was starting to sink in. These results are presented in Figure 4.3.

Figure 4.3 Comparing 2004 to 2006 Culture Survey: Polar Bank

Polar Bank's second survey also showed substantial progress in two other areas. The level of teamwork had improved by more than thirty points. Their progress in organizational learning, where they had improved by fifty points, was mostly in the area of risk and innovation, again showing that the areas they had given the most attention showed the biggest improvement.

The Polar Bank scores also showed that they remained strong in empowerment and capability development, confirming that they had never strayed far from their strengths as a good employer even while they were carrying out all of these changes.

Perhaps the most frustrating part of these results, however, was what had not improved. Customer focus remained at a low level, showing little or no improvement. In addition, nearly all of the measures of consistency had stayed right where they were in the first survey. Perhaps the groundwork had been laid for a common infrastructure and set of values, but they were still a long way from creating one common operating system.

Lessons for Leaders

Leaders must recognize the strong subcultures in their organizations. They arise from influences both from within the organization and from the outside. In some organizations—like a holding company, a conglomerate, or another highly decentralized organization—this level of fragmentation can be desirable. Nonetheless, most organizations try hard to create a common culture and integrate the pieces into a compelling whole. Polar Bank made a clear strategic choice to forgo the option of continuing to operate as three separate banks and to become a full-service bank with cross-border business units.

But changing culture is hard work, and it needs to take place at a very practical level. Hansen could never have made the progress that she did by simply stating: “Polar Bank will have one overarching culture” and then hoping that it would happen. She learned that you need to take strong, concrete actions if you want culturally distinct businesses to behave in the best interests of the overall company.

Create a Common Governance Structure

One of the best lessons from Polar Bank comes from their decision to create one common board of directors to govern all three banks. Having the same identical board for all three banks created a common governance structure and significantly reduced the internal power struggles. Concern about the power differences among the banks became secondary to their shared interest in having each of the three banks operating successfully and all moving toward a future in which they could work together to exploit their complementarity and achieve the new dynamic capabilities required to fulfill their strategic mission.

Few companies that we know of have used this approach to resolving governance issues in the same way that Polar Bank has. A more common practice is for some exchange of board members and roles between companies. For example, in the pharmaceutical industry, when DSM acquired Roche Vitamins in 2002, a member of the DSM executive board became the chairman of the newly acquired company, and DSM also appointed one of their own executives as the new CEO of the vitamin business.

Engage the Leaders in Building a Common Strategy

When striving to achieve one overall company culture, different business units have to understand each other's strategies. Another good lesson from Polar Bank's experience was the impact of their efforts to involve senior executives and high-potential managers of each of the three banks in the strategy development for all of the banks. The time that the leaders spent together understanding each other's strategies also helped them understand each other's operations, markets, products, people, and culture, as well as their strengths and weaknesses. It served as a general mechanism by which the three banks could learn about each other's businesses as well as the primary purpose of crafting a common strategy.

Although we have not seen cross-business strategy development to this same extent in other companies, we have seen some other interesting examples. In one European pharmaceutical company, for example, they required very broad involvement in the continued development of the corporate strategy. Every five years they go through a process known as the corporate strategy dialogue (CSD). Hundreds of managers, from all levels, are involved in the process. In addition, when the business units translate the corporate strategy into a strategy for their own business unit, they typically ask executives from some of the other business units to conduct a critical review of their plans.

Build Cross-Business Capability

Polar Bank also built cross-business capability by establishing a system of job rotation. The career paths of the high-potential leaders in all three banks now would require spending several years in at least one of the other banks. This was often quite unpopular, because it required successful people to move outside of their home country and to take some new risks. But it was also extremely helpful in identifying those individuals who were truly committed to the cross-border mission and strategy.

However, talking about job rotation and actually doing it are two different things. One other company that we worked with also instituted a system of “job rotation.” It all sounded good in principle; in practice, though, all of the rotation went one way. Senior managers from the acquiring company were “rotated” to important positions in the acquired company. But the people whose jobs they were rotated into soon found out that they were being “rotated” out of the company. It did not take people long to see that this was all about the victors claiming the spoils, and the acquiring company imposing its culture on the acquisition, rather than working on the creation of a best-of-both culture by moving people both ways.

Make Quick Decisions About Managers Who Aren't Aligned

Katarina Hansen was also quite deliberate in her decisions about those executives who weren't aligned with the transformation she was trying to achieve at Polar Bank. She was patient, and she gave managers ample opportunity to show their energy and alignment. She definitely didn't “shoot from the hip.” But when it was clear to her that some of her team members were not supportive of the strategy and the culture changes that were required, she took quick action. Getting the team right from the beginning is always the first step in the integration process.6

Creating One Culture Out of Many: Beyond Polar Bank

We once worked with a UK-based beer company that had grown significantly through a decade of acquisitions. Repeated attempts to integrate the acquisitions into one organization proved difficult and never created nearly as much excitement and energy among the top leaders as the next acquisition target. They saw the discussion of “creating one culture” as a fluffy discourse about values and purpose, but at the same time they were constantly frustrated with their repeated failure to establish a common framework so that they could implement basic business decisions—like rationalizing production and establishing a common branding and distribution system across their far-flung empire.

Still, some of their people kept talking about their values and their culture. One evening the EVP for HR took me aside and talked for a few minutes about those who were suggesting that the leadership team should spend more time talking about their own core values and paying more attention to the creation of a common culture. He asked me if I would be able to meet with their management team sometime soon to discuss this issue with them and help them decide their next steps.

“What do you want to achieve?” I asked him.

He looked at me, raised one eyebrow, and said, “We need to make sure nothing happens!”

I took a long walk back to the hotel that evening.

A few years later, they received a good offer from one of their competitors to buy this whole collection of unintegrated acquisitions. It was a great opportunity to sell both the problems and the possibilities on down the line. They took the offer. Live by the sword, die by the sword. Integrating acquisitions is a lot of work!

Creating an Integration Plan

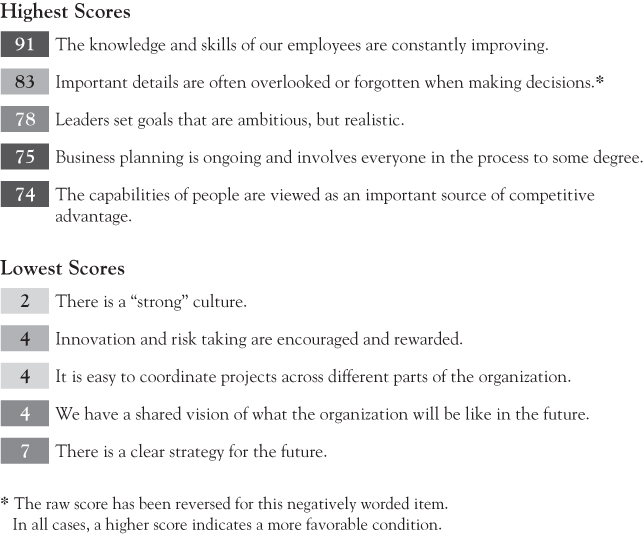

The classic way to frame this discussion, after many years, is still the Mirvis and Marks model, presented in Figure 4.4. In their 2010 book, Joining Forces: Making One Plus One Equal Three in Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances,7 they compare the degree of change required in the acquired company with the degree of change in the acquiring company. From this they describe five different types of mergers.

- “Stand-alone” mergers, which require little change in either company

- “Absorption” mergers, in which the acquired company must change dramatically so that it can be absorbed by the acquiring company

- “Reverse acquisition” mergers, in which the acquiring firm must change dramatically to take on many of the characteristics of the acquired firm

- “Transformational” mergers, which require dramatic changes from both organizations

- “Best of both” mergers is a middle ground requiring a moderate level of change in both organizations

Understanding these categories always serves to clarify the power dynamics and complexities that are associated with any merger. But confusion over which category best fits the situation is always a sign of trouble.

The second step in the Mirvis and Marks framework addresses the question of how much integration is needed. Where? When? Why? In what order? Should the components of the new organization just be separate parts of a common holding company? Or should they be fully merged and consolidated? There are many attractive midpoints along the way. Different business units and functions may also require different strategies, and some of these targets of integration may evolve from one category to the other over a period of several years. A detailed integration plan is the best resource to create to guide the integration process (see Figure 4.5).

It is also important to recognize that the similarities and differences between two corporate cultures can be a source of both strength and challenge. Organizations usually look for similarities first and tend to see those as strengths. Our favorite example of this comes from IBM Consulting's acquisition of PricewaterhouseCoopers Consulting.8 As the integration team completed their due diligence on the two companies, they noted some remarkable similarities in the organization structures, market strategies, and company values. Then, when the combined executive leadership team was able to rapidly agree on their new operating principles, it seemed to some of the leaders that the two organizations were really like “twins separated at birth!” In the beginning of the “hunt” it is easy to underestimate the complexities of the integration process.

But it is also important to see that the complementarities between very different cultures, if managed well, can be a tremendous source of strength. Large, stable technology companies often acquire small, dynamic start-ups to drive their innovation and growth. When the process is managed correctly, the combined organization is able to achieve leverage on their innovative ideas in a way that the start-up alone never could. When pharmaceutical companies make R&D acquisitions, they may pay a high price, but they may be able to achieve greater return on that investment than they can from the same investment in their own R&D labs.

Cultural incompatibility is, on occasion, a good reason for avoiding an acquisition target altogether. But more often, if an organization pays careful attention to the cultural complexities of the integration process, and combines that with a thoughtful integration plan that maintains the right balance between patience and urgency, it can beat the odds and manage its way to a successful outcome.

Notes

1 Yip, George, and Bink, Audrey J. M. Managing Global Customers: An Integrated Approach. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

2 Denison, Daniel R., Adkins, Bryan, and Guidroz, Ashley M. “Managing Cultural Integration in Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions.” In Advances in Global Leadership, edited by William H. Mobley, Ming Li, and Ying Wang, vol. 6, 95–115. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 2011.

3 Marks, Mitchell Lee, and Mirvis, Philip H. Joining Forces: Making One Plus One Equal Three in Mergers, Acquisitions, and Alliances. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010, p. 4; Mirvis, Philip H., and Marks, Mitchell Lee. Managing the Merger: Making It Work. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Professional Technical Reference, 1991.

4 Schraeder, Mike, and Self, Dennis R. “Enhancing the Success of Mergers and Acquisitions: An Organizational Culture Perspective.” Management Decision 41, no. 5 (2003): 511.

5 At the company's request, we use a pseudonym for this financial services firm.

6 Collins, James C. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap—and Others Don't. New York: HarperBusiness, 2001.

7 Marks and Mirvis, Joining Forces.

8 Moulton Reger, Sara J. Can Two Rights Make a Wrong? Insights from IBM's Tangible Culture Approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, 2006.