Chapter 2

Supporting the Front Line

Japanese scholar Ikujiro Nonaka first rose to fame in his home country with his analysis of the role of the U.S. Marines in the Pacific theater during World War II.1 The Marines, he argued, were amphibious warriors, who moved from the sea onto the land with a discipline that the Japanese generals had never seen before. Nonaka seized on the critical importance of those who stormed the beaches first—the “gravel crunchers” as the Marines called them. It was a dangerous job. Even when the mission was “successful,” the gravel crunchers could often end up dead, face down in the water, with tank tracks up their backs. But the tanks were on the beach! So in order to succeed, the Marines needed to make certain that they did everything that they could do to support the gravel crunchers, because they were “the sharp end of the spear”—if they didn't succeed, the entire mission would fail. This image teaches us the first lesson of building a successful corporate culture, especially in the service industry. Support the front line! Everything depends on their success and their survival.

JetBlue Airways learned this lesson the hard way. Their unique high-involvement culture and friendly customer service initially helped make them the fastest-growing airline in the competitive U.S. market. In 2006, for example, they set a record by opening fifteen new routes in an attempt to consolidate their position in the market. But this dramatic increase in traffic stretched their growing human and organizational infrastructure to the limit. On Valentine's Day 2007, they reached their limit. In a fierce ice storm at New York's JFK International Airport, their operational infrastructure broke down, leaving passengers stranded on the runway for hours. The return to “normal” took three days, with the disruption continuing long after the ice storm had passed. JetBlue's well-deserved reputation and carefully crafted brand took a major beating in the media.

But rather than retrenching to a more traditional command-and-control structure, JetBlue's approach to solving this problem reinforced the unique high-involvement culture that had fueled their rapid growth in the first place. They didn't take a top-down approach to creating the infrastructure needed to recover from this operational setback. Instead, they brought together a broad, cross-functional coalition of frontline crew members. This team, with full support from the top, developed the JetBlue strategy for recovering from an interruption in service and solved this problem so that it would never happen again. And it hasn't.

Creating a system that supports the front line makes all the difference, no matter where you are in the world. The Chinese company Galanz, now the world's largest producer of microwave ovens, is built around teams, and they work hard to develop human capability at all levels. This is an important advantage in the hypercompetitive Chinese labor market. Galanz is run like a family, striving to develop a culture of emotional attachment between the company and its employees. Liang Qingde, the founder and chairman of Galanz, is called “Uncle De,” and employees call each other “Brother X” or “Sister X” like they are a part of a family. At the end of each year, Uncle De writes a letter to all employees and their families, expressing appreciation for their work. Galanz's success in supporting their forty thousand employees helped them reach US$2 billion in revenue for 2008. Employees are supported in a very different way from how it might be done in a Western organization, but the effect is very similar.

The challenge of supporting the front line is important in all organizations, but it is especially important in service organizations, where the product is produced as it is delivered. Whether your organization is a brokerage or a burger stand, a franchise or a fraternity, a hotel or a hospital, a college or consulting firm, you cannot function effectively without high-quality human interaction with your customers. Without the involvement of the front line, you can't really deliver the most important part of the organization's strategy: implementation. And as far as we can tell, the market doesn't pay many rewards to strategies that aren't well implemented. Without the right mindset and behavior on the front line, there is no strategy—only a set of unexecuted plans.

Making the Front Line the Foundation of Your Strategy

In this chapter, we focus on Domino's Pizza, which gives us an example of an organization that took a big step forward in quality and performance when they finally decided that they needed to make their people the foundation of their competitive strategy.We tracked this story very carefully over a number of years. So let's start from the beginning.

Domino's Pizza was founded in 1960 by two brothers, Tom and Jim Monaghan, who each kicked in $500 to buy a pizza shop. Before long, Jim wanted out, so he traded his half of the store to Tom in exchange for Tom's well-used Volkswagen Beetle. In his thirty-nine years of leading the company, Tom Monaghan transformed this one pizza delivery shop into one of the world's top brands. In 1999, with six thousand stores and over $3 billion in revenues, Monaghan sold 93 percent of the company to Bain Capital, which soon brought in David Brandon as CEO.2

How do you go about creating competitive advantage in the pizza delivery business? Is it the pepperoni? The cheese? Maybe the anchovies? The new CEO and his team made the decision that the only way to create competitive advantage in their business was through the people. In his first week on the job, Brandon learned that the annual staff turnover was 158 percent. After doing the math, he realized that with 150,000 people, the company might have trouble finding enough time to make pizzas and deliver them if they had to continue hiring and training nearly a quarter of a million people each year. What stunned Brandon even more was the current HR leader's acceptance of this level of turnover as being “normal for this industry.” Brandon soon recruited a new HR executive from outside the industry. She was Patti Wilmot, and she was ready for the challenge.

Brandon took over at Domino's after a career that started at Procter & Gamble on the recommendation of his football coach at the University of Michigan. He'd gone on to become the CEO of a direct marketing company, Valassis Communications, which he grew from a firm with a few hundred employees to a spot on FORTUNE's 100 Best Places to Work list. Here's what he said to his people the first day on the job at Domino's:

If you don't remember anything else about me today, just remember these three words—Change is good. Change is not a criticism of the past. It just means the future is going to be different. If that sounds exciting to you, you're going to love me. If any of you are thinking “I'd rather do things the way we've always done them,” I've got to tell you—you're going to hate me.3

Whether he was leading several thousand Domino's people shouting out the Domino's vision—“We are exceptional people on a mission to be the best pizza delivery company in the world!”—or teaching finance to new store managers, or convincing skeptical industry analysts, Brandon always preached Domino's four guiding principles: “People First,” “Build the Brand,” “Maintain High Standards,” and “Flawless Execution.” Domino's staff had worked together to develop these guiding principles during the first year of the transformation.

They made every attempt to improve the quality of the workforce. Hiring placed more emphasis on attitude because they felt that skills could be taught, but attitude could be stubbornly permanent. Drug testing for delivery drivers, new financial software designed to prevent “shrinkage” and theft, and a ban on hiring former employees who had been fired were all implemented to help improve the quality of the workforce.

Each segment of the employee population received special attention. A “pipeline” was created for each segment that defined hiring criteria, developmental targets and investments, advancement opportunities, and exit plans. The pipeline was managed for all segments of the employee population, from pizza delivery boys to store managers and franchisees to future executives and board members. Poorly performing franchisees, in the bottom 25 percent, were also invited to “straight talk” sessions where they discussed their store's performance. Part of the discussion always focused on the business potential of a well-run franchise. If a franchisee would not devote the time and attention it took to be successful, Domino's was always ready to help them or to help broker a deal to sell their underperforming stores to another franchisee.

Domino's performance steadily improved. After their 2004 IPO, Bain Capital noted that Domino's was one of the best private equity deals that they had ever done, returning over 500 percent on their investment.4 Involvement, capability, and teamwork were the hallmarks of their success.

Tracking the Progress

We tracked Domino's progress over five years, as this transformation unfolded. The tracking process was designed to make sure that the progress that the organization was making wasn't just in the minds of the executives in the C-suite, but that things were really starting to change on the ground. The survey was based upon our organizational culture model, and it included all of the levels of management as well as the people in the stores.

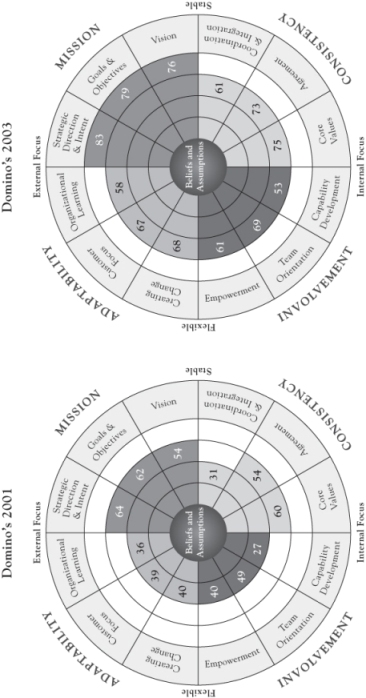

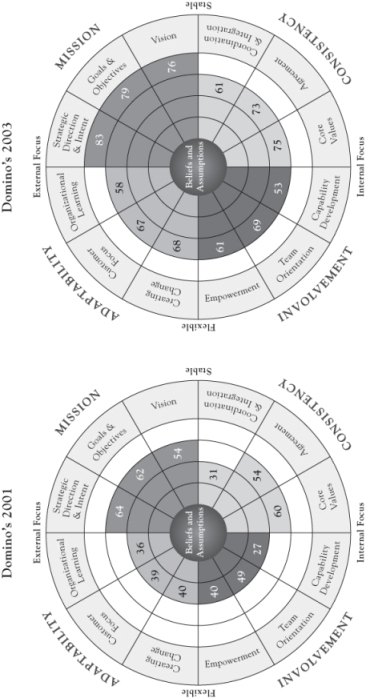

The baseline culture data from 2001 are presented in Figure 2.1. These results show that Domino's started with some clear challenges: Capability Development, Coordination and Integration, Customer Focus, and Organizational Learning were all below the fortieth percentile when compared to the global benchmark.5 The survey results also helped Brandon and his leadership team to clarify their goals for transforming the organization. The low scores in the involvement area—in capability development, in particular—confirmed that Domino's had their work cut out for them when it came to improving the capability of their people on the front line. These results in Figure 2.1 summarize the perspective of management as a whole. But when we looked in more detail at the lower levels of management and the people in the stores, the involvement scores are even lower. When Domino's compared their culture scores for the higher- and lower-performing stores and regions, they found that the culture at the region and store level also made a big difference.

Figure 2.1 2001 Culture Survey Results: Domino's Pizza

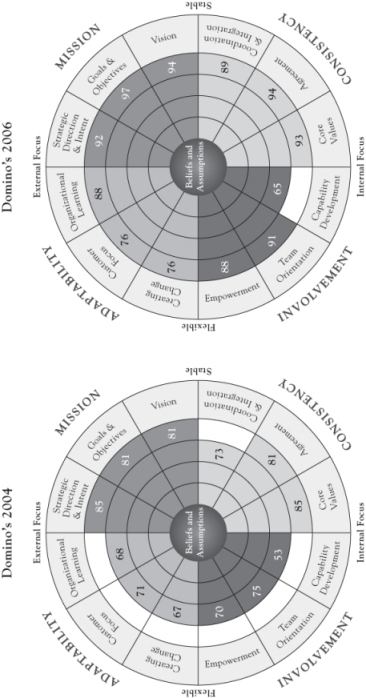

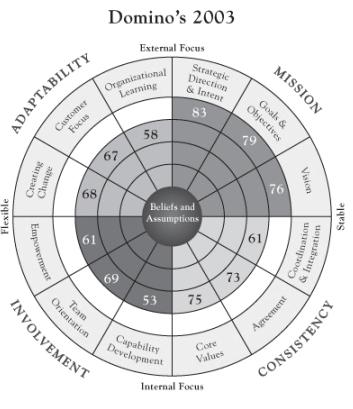

They set goals to cut employee turnover in half and to be acknowledged as one of the one hundred best companies to work for in America. They also focused on a clear set of business goals, setting their target on being “Wall Street ready” so that they would be prepared for an IPO in the near future by hitting their targets of ten thousand stores and $200 million EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization). The survey results from 2003 (Figure 2.2) show the progress that they had made. Domino's had taken big steps forward in the areas of Coordination and Integration, Customer Focus, Creating Change, and Capability Development. They were now at least slightly above average on everything, with real strengths in all areas of Mission. These results show the clear effects of two years of hard work in clarifying the direction of the organization and setting clear expectations about the level of ambition that was expected from the people.

Figure 2.2 Comparing 2001 to 2003 Culture Survey Results: Domino's Pizza

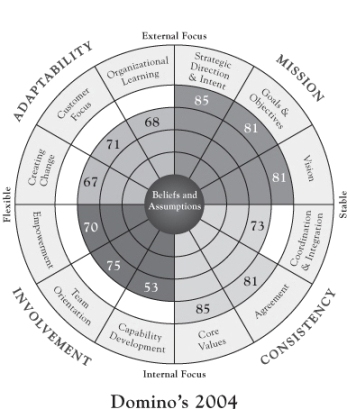

But they didn't stop there. Their survey results from 2004, presented in Figure 2.3, show that they had continued to make forward progress as they drove the transformation deeper into the organization. The feedback about their progress and their challenges was shared widely in the company. and all of the managers involved went through a goal-setting process that they called SMAC. This involved discussing their results, linking them to the real business issues behind the results, and then creating a set of action steps that fit the SMAC criteria: the goals had to be specific, measurable, achievable, and consistent with the overall direction of the company. This focus on action helped them to continue their progress.

Figure 2.3 Comparing 2001–2004 Culture Survey Results: Domino's Pizza

Following their successful IPO in 2004, Domino's actually accelerated their rate of change. They made some dramatic changes in their people policies that showed a clear impact on the survey results in 2006. These changes were all designed to continue on the path of improving their competitive position by improving the quality of their workforce. They decided that there would be no rehires and no demotions. Although this may sound like a simple HR policy change, consider the impact that it would have. Before this policy was established, many delivery drivers, for example, would work at one store for a while and then, maybe at the end of the college semester, just stop showing up for work; the following year, when they wanted another job, they would show up at another Domino's and get hired back.

At first, store managers objected to the new policy, because it placed some limitations on their ability to hire new drivers. But over time, these changes, along with mandatory drug testing and new store-level software that made it easier to identify “shrinkage” and dishonest store managers, steadily increased the quality of the workforce.

Domino's also focused quite explicitly on getting rid of what they called “coalitions of the unwilling.” Those who weren't really “exceptional people on a mission to become the best pizza delivery company in the world” began to stand out against the backdrop of a growing number of people who were on that mission. Attitude and ambition mattered a lot. The leaders took the positive energy and ambition of their people very seriously. They gave a lot, but they also expected a lot in return.

As mentioned earlier, during this time Domino's also made great progress in segmenting the workforce in the entire organization and defining the “pipeline” for each position. From delivery drivers to store managers to vice presidents and future members of the board, each target group understood its pipeline. Which people are at what stage? Who is ready for the next step? What support do they need? Where does the organization need greater depth? The support and energy were very positive, but the organization and its people were held to a higher standard than they had ever seen before.

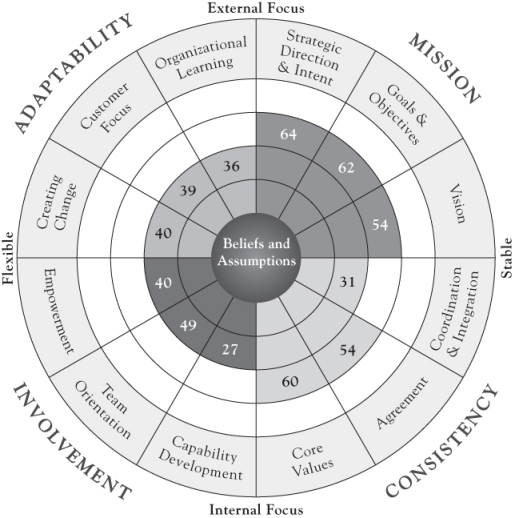

The Hard Work Pays Off

All of this hard work on improving the organization and the quality of the workforce paid off in the performance of the business. Domino's met most of the goals that they had set at the outset of this transformation, and they made excellent progress against even those goals that they did not meet. Employee turnover was dramatically reduced; profitability, market share, and shareholder returns were increased; and they came close to meeting their goal of being one of the one hundred best companies to work for in America. There are still many challenges in this organization, and they have suffered through several setbacks. But overall, Domino's gives us a great example of how an organization can transform itself by focusing on the way it supports its frontline people. Over the course of five years, Domino's had improved their organization and culture in many ways and created much greater capability on the front line. They received top scores in nearly all areas (see Figure 2.4) and faced the next set of challenges to sustain this high performance culture that they had built.

As mentioned earlier, this transformation also created exceptional value in the marketplace. Domino's became one of Bain Capital's most successful investments, returning 523 percent on their equity investment. On a pizza delivery chain! Mark Nunnelly, managing director at Bain, gave Brandon a lot of credit: “You could put him in the middle of any company and he knew how to focus on key issues. I wish I could clone him.”6

Source: Denison and Lief, 2008.

Lessons for Leaders

There are many lessons about changing the culture of an organization to better support the front line that we can draw from Domino's experience. Like all transformation efforts, it is an interesting mix of changes in mindset and systems, structures, and behaviors, which combines both the magic and the method of a successful change. The survey process helped confirm some of the basic strengths and challenges, and it helped lead Domino's to define a new set of values and behaviors and the policies to support them for the future. Let's look at some of the lessons we can take from their experience.

Lead with a Personal Touch, But Follow Up with Structure

It's hard work to get a culture change process started, but it is even harder work to keep it going. Domino's case is remarkable for how long they sustained the transformation process. It is great to talk about “creating a burning platform,” but it is more important to understand how to keep the fire going without burning down the house.

The Domino's transformation started largely because of a new CEO with very high expectations, who was positive, inclusive, open, personal, and very visible. Suddenly, everything seemed possible. It was an exciting time. They tell a story about the first time that Brandon went to Mexico City to meet with the Mexican franchisees. When the staff who were organizing the event asked Brandon about his plans for the two-hour meeting, he said that he would just like to make a few opening comments for twenty to thirty minutes and then do Q&A. The staff sat in stunned silence. Domino's had never done a franchise meeting this way before. Typically, the meetings were tightly scripted with a clear agenda with little room for Q&A. After a lot of discussion and extensive nail-biting, they decided to do it Brandon's way. And it was the best meeting that they had ever had with their Mexican franchisees—the message was clear that Domino's had a new energy and flexibility and was fully committed to listening and learning with the franchisees that make up 90 percent of their worldwide sales and to supporting them in the best way that they could.

But unlike many organizations with charismatic leaders, Domino's was also very savvy at creating the structures that sustained that energy and momentum. Creating an enduring system with the structure that exemplifies the new core values lies at the heart of every sustainable culture transformation. For all of the books that have been written about transformational and charismatic leaders whose personal qualities win the day, there is an amazing shortage of books about how successful leaders create structures that leverage the personal characteristics and the values at the core of their transformations. Mindset and systems are often two sides of the same coin. A commitment to improving the quality of the people and listening to the marketplace and the front line is an important value, but the transformation doesn't create much leverage unless leaders create the systems necessary to scale up those values until they reach everyone in the organization—without losing energy and focus.

We Are All in the Service Business

Domino's transformation began when they saw their business through new eyes as a service business that delivered a product, rather than a product business with a lot of delivery people. The difference is simple, but profound: Most of the time, there's not as much difference in the quality of the pizzas that get delivered to your front door as there is in the quality of the people who deliver them. The primary focus of the entire organization needs to be on supporting those who deliver that customer experience.

The fundamental difference in the service business is that the product can never be created independent of the customer experience. So, this means that the front line experience is the product, it is the strategy, it is the organization. There's really no way around it. And the rate of innovation in the customer experience our organizations provide is relentless. The best never rest. But it also requires coordination and consistency! The “frontline” experience for the customer may be a salesperson, a service person, a flight attendant, a driver, a website, an ATM, or someone from tech support. In practice, the front line is the combination of all the ways in which the organization touches the customer. And if the customer experience doesn't add up, guess who takes the fall?

Over most of the twentieth century, production power reigned supreme. If you had the capability to produce the best, the market would follow. Build a better mousetrap, and the world would beat a path to your door. But those days are long gone. Today's power lies with those on the other end of the value chain—those who are closer to the marketplace and the customers. This means that the balance between the value of product knowledge and market knowledge is changing. So is the importance of market knowledge in the mindset and culture of the organization. And this change is happening fast.

Several years into the Domino's transformation, President (and now CEO) Patrick Doyle was planning a tour of some of Domino's stores. He knew that it was very important to be visible on the front line so that his support was clear. But where should he start? There were many choices. His decision was to go directly to individual stores and deliver the message, “We appreciate what you do!” His Appreciation Tour was controversial. Shouldn't the president make an important strategy presentation or give an outline of the goals for this quarter? Or talk about the stock price? Or the competition? Or something really important to the business, like the rising cost of wheat?

No. Instead, in each of the sessions Patrick said a few words about how important the people he was meeting were to Domino's and how much he and the company appreciated them. Then they ate pizza and talked. The president may have gained a few pounds, but he also gained a lot of support from the front line.

What You Keep Is as Important as What You Change

Any way you slice it, Tom Monaghan was a genius at running a pizza shop. From the invention of the “spoodle” by Jeff Goddard, the winner of the 1985 world's fastest pizza maker competition,7 to the “HeatWave” hot pack for keeping pizzas warm, to the magnetic 3D car-top signs that are now used by many other companies, Domino's boasts an endless string of innovations that have helped perfect the art of running a pizza store. Training standards for new employees require that they be able to make a quality pizza in under one minute. (The fastest pizza makers can make three pizzas in one minute!) In fact, during the Domino's transformation, the Investor Relations team was thinking about ways that they could reconnect with the simplicity of their business and reconnect with the front line. Their solution? They decided, as one of their development goals for the year, that all of the members of the Investor Relations team should be able to make a pizza to the Domino's standard in under one minute. It took some of them a while to master this, but they did it.

Monaghan also created an organization structure that required a clear focus on the pizza business. Each franchisee's contract includes Domino's well-known “OBI” provision. A franchisee cannot have any other outside business interests. Signing a franchise agreement forces the franchisee to make a commitment to focus exclusively on the Domino's pizza franchise. The company allows some flexibility on this, especially in developing master franchisee relationships when entering new countries. But overall, the new business structure that they've created gives remarkable focus to their efforts. The basic formula is simple: A franchisee with one store has a full-time job and a good income. A franchisee with two stores has two full-time jobs and a very good income. And a franchisee with three stores has three store managers, a full-time job, and a very good income.

Change is good, but successful culture change is not change for change's sake. Developing a clear sense of the policies and practices that need to be preserved and strengthened is an important component of every successful transformation. Domino's makes the point very clearly: Many of the elements of running a successful pizza store have remained unchanged. But the role of the corporate center and the company-owned stores has changed dramatically—these parts of the organization have moved from being the stronghold of the traditionalists to being the core of the innovation process. And one of the most important changes in the role of the corporate center was to work relentlessly to create a system that would dramatically improve the quality and engagement of the people on the front line.

Strategies for Supporting the Front Line: Beyond Domino's

Chris Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal positioned the support of the front line as a clear strategic choice for organizations. They argued that many companies are still run with a logic that tries to make the firm immune from human errors.8 They argue that rather than trying to take the human factor out of the equation and make the organization run like a machine, companies are far better off if they build an environment that harnesses the power of the capabilities of their people.

The themes of participation, involvement, empowerment, and engagement have been with us for a long time. From classic authors such as Douglas McGregor,9 Rensis Likert,10 and Ed Lawler11 to more recent authors such as John Kotter12 and Jim Collins,13 many management gurus have argued that the link between the individual and the organization is critical to an organization's success.

Many organizations have focused primarily on the psychological state of their employees. After all, this is the desired result—engaged employees who are committed, satisfied, and productive. But focusing only on these desired outcomes misses the most important point: What organizational conditions are the causes for these effects?

You can identify the organizations that have been too influenced by this approach. They often know what they want to achieve for their people, but they are having trouble getting there. The managers talk a lot about “keeping our people happy,” but the employees complain that their leaders don't “walk the talk”; the employees then tend to get cynical about attempts to improve things. One manager we met said that he always felt as if he were trying to win the “engaged manager of the year” contest. He saw his organization's engagement efforts as a popularity contest to keep employees happy without really changing very much, rather than a serious attempt to try to improve the organization.

Effective organizations need to focus instead on the environment that they create for their frontline service people. To achieve the desired effect of engaged people on the front line, organizations and their leaders need to be experts in the organizational causes that are necessary to support those frontline people. Organizations that do a good job of supporting their frontline people understand that the psychological state of mind is important, but they focus most of their attention on the working conditions created by their management practices. They are constantly working to improve their culture.

Support Is Strategic: Mickey Mouse Versus the Street Sweepers

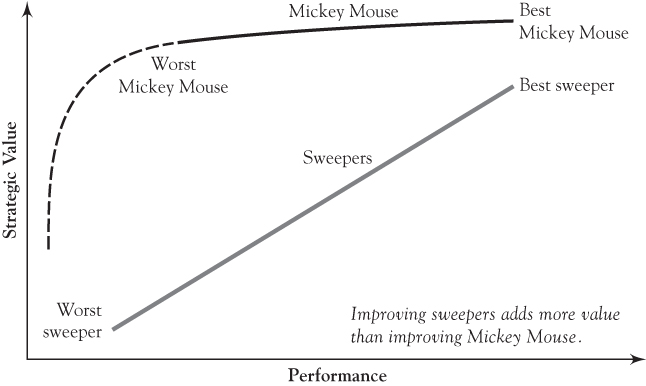

Supporting the frontline jobs that have the biggest impact on an organization's customers and their business is probably the most important part of the strategy implementation process. One company that is a perennial leader in this type of thinking is Walt Disney. HR guru John Boudreau shows us how important it is to have a well-conceived strategy for supporting the front line by analyzing the relative importance of the skill levels of Mickey Mouse performers and the sweepers in a Disney theme park.14

Mickey Mouse is a very important part of any visitor's experience in a Disney theme park. Mickey gives a warm and friendly greeting to millions of visitors each year. It is a memorable experience and the ideal family photo op. But it doesn't last long. There's little room for improvisation on Mickey's part, and thus, despite the critical importance of Mickey to the overall theme park experience, there is only a small performance difference between the best and the worst Mickeys.

The theme park's street sweepers, however, have a much more pivotal role. As Boudreau notes, the sweepers play a highly important role in customer relations. “People seldom ask Cinderella where to buy a disposable camera, but hundreds a day will ask the street sweeper!”15 The sweepers need to understand the strategic importance of their role, but this works only if the organization creates a system that recognizes that the sweepers are frontline customer service experts who happen to carry brooms. Selection, training, development, rewards, and future opportunities are all designed to create this context to support their role. Boudreau summarizes this in a graph (Figure 2.5) that shows us why there is more value in improving sweepers' performance than there is in improving Mickey Mouse's performance. It's the context that the organization creates for the street sweepers that makes them highly engaged and highly effective.

Tom Davenport offers additional examples.16 Harrah's Entertainment studies their organization to the point where they have developed a model that tells them the right number of people to have at the front desk and other key service points throughout the daily cycle. Voilà! They have a dynamic plan that allows their people to react to the changing customer expectations. How happy and engaged can employees be if they never have enough people to cover the front desk? Global food service giant Sysco discovered that the biggest positive impact on customer service came from their experienced delivery associates—those people whose daily deliveries are the lifeblood of every restaurant that they serve. Increased dedication to this pivotal group of frontline people increased their retention rate from 65 percent to 85 percent over six years, leading to major benefits in increased customer satisfaction as well as decreased training and hiring costs.

Know More, Care More, and Contribute More

There are so many great examples of how to support the front line that it's difficult to understand why some organizations get it so wrong. The truth is that this is much easier said than done. A competitive advantage based on people can take years to create. But it also takes years to imitate, and thus gives a great advantage to those who know how to walk the talk.

One of the early leaders in understanding the importance of supporting the front line was Edward E. Lawler III. Lawler argued years ago that the future world of work would require the workforce to “Know more, care more, and contribute more.”17 Frontline workers, he argued, always need to know more and to learn more about their job while they master the new skills that contribute to the business. They also need to care more and have higher emotional involvement in their work and a greater motivation to understand the world from their customers' point of view. Finally, people on the front line need to contribute more. The demand in the marketplace for quality service continues to grow, and the organizations that contribute the most will be the ones that will thrive.

But although Lawler intended these comments for the workforce, it is striking how well they apply to the managers and leaders of organizations, who need to learn the lessons of creating an organization that supports the front line. Their challenge may well be the bigger one: They need to create the set of conditions that allow their frontline people to know more, care more, and contribute more.

We close this chapter with Jon Katzenbach and Jason Santamaria's five guidelines on how leaders can create systems that support the front line.18

•Overinvest at the outset in inculcating core values. You never get a second chance to make a first impression. Leading companies select people based on the fit with their core values, in anticipation that each new hire will play an important role with respect to the implementation of the strategies of the future. The most important part of each new hire's onboarding experience is not only the skills that they learn, as important as those are, but also about the importance of the core values of the firm.

•Prepare every person to lead, but especially the frontline supervisors. Organizations that teach their people that leadership happens only in the executive suite are headed for trouble. The best organizations recognize that leadership has to happen at all levels. To support the front line, it is essential that an organization invest in talented management at the level of the frontline supervisors. Once the chain of command is broken and the front line is disconnected from the rest of the organization, it is hard to put it back together.

•Distinguish between teams and single-leader work groups. Supporting the front line means establishing clear accountabilities and decision rights. Fuzzy accountabilities should never be confused with “empowerment.” Establishing teams that have collective responsibilities and distinguishing them from individual leaders and supervisors who lead a work group is essential to building a collective sense of responsibility.

•Attend to the bottom half. Who gets the most attention? Who has the biggest impact? Every organization can be improved by bringing the bottom half up the middle. You know who they are, where they are, and how they impact the business. And you know how to improve their performance. This is not rocket science. It's much harder! Because it requires not a brilliant conceptual solution, but consistent support and day-to-day commitment .

•Use discipline to build pride. If you don't stand for something, you'll fall for anything. A strong set of expectations builds a strong team. A clear standard that everyone must meet means that this is a team or organization that is worth belonging to. Without discipline, it is hard to build a strong sense of pride in belonging.

The role of middle managers is to link the vision of the top to the realities of the marketplace. Want to know how you are doing? Go ask your people on the front line. That's the moment of truth.

Notes

1 Nonaka's writings on the Marines have never been published in English. This research is described briefly in his well-known book with Hiro Takeuchi, The Knowledge Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

2 Bourdet, Dorothy. “Domino Effect: David Brandon Has Pizza Chain Shaking and Baking.” Detroit News, December 9, 2006, p. 1.

3 Denison, Daniel R., and Lief, Colleen. “Domino's Pizza: Change Is Good.” International Institute for Management Development, Lausanne, Switzerland, IMD 3–1839, 2008.

4 Ibid.

5 See the Appendix for an overview of the Survey results.

6 Denison and Lief, “Domino's Pizza, ” p. 7.

7 The spoodle is a unique combination of a spoon and a ladle, with a measuring cup on one side that ensures that you have exactly the right amount of sauce for a pizza, and a flat surface on the other side for spreading the sauce.

8 Bartlett, Christopher, and Ghoshal, Sumantra. “Building Competitive Advantage Through People.” Sloan Management Review, January 2002, 34–41.

9 McGregor, Douglas. The Human Side of Enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1960.

10 Likert, Rensis. New Patterns of Management. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961.

11 Lawler, Edward E., III. High-Involvement Management. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1986.

12 Kotter, Leading Change (see ch. 1, n. 31).

13 Collins, Good to Great (see ch. 1, n. 28).

14 Boudreau, John W., and Ramstad, Peter M. Beyond HR: The New Science of Human Capital. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2007; Likert, Rensis. New Patterns of Management. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1961.

15 Ibid., p. 54.

16 Davenport, Thomas H. “Competing on Analytics.” Harvard Business Review, January 2006, 2–11.

17 Lawler, Edward E., III. High-Involvement Management. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1991.

18 Katzenbach, Jon R., and Santamaria, Jason A.