Chapter 1

Building a High-Performance Business Culture

Every human organization creates a unique culture all its own. From a small family business operating in its hometown, to a large global corporation spanning national cultures and time zones, each organization has a distinct identity. Tribes, families, cults, teams, and corporations all develop a complex and unique identity that evolves as they grow through the years.

Their culture always reflects the collective wisdom that comes from the lessons people learn as they adapt and survive together over time. Thousands of interlocking routines knit together the fabric of the firm and translate timeless knowledge into timely action on a daily basis. The traditional habits and customs that have kept the firm alive and well over time speak loud and clear. And when uncertainty rears its ugly head, the culture rules! All members of the corporate tribe tend to fall back on their tried-and-true methods in order to weather the storm.

Yet try as we might to look to the future, the knowledge embedded in our corporate cultures is always yesterday's knowledge, developed to meet the challenges of the past. What part of the past should we preserve for the future? How should we adapt the principles of the past to address the problems of the future? How should we go about the delicate task of relegating the obsolete practices of the past to the “corporate museum” so that they don't grow into obstacles that hold back our best practices and frustrate our best customers?

Some leaders try to ignore these challenges and concentrate on their expense ratios, analyst reports, discounted cash flows, and their next acquisition. Bad idea. Other top executives see shaping and managing the corporate culture as one of their most important challenges. As Wells Fargo Bank CEO John Stumpf said, “It's about the culture. I could leave our strategy on an airplane seat and have a competitor read it and it would not make any difference.”1 Former IBM Chairman Lou Gerstner made the same point: “Culture isn't just one aspect of the game—it is the game. In the end, an organization is no more than the collective capacity of its people to create value.”2 The people make the place.3 The people create the organization. The people create the technology. The people organize the funding. The people develop the markets. Without implementation and alignment, there is no strategy, only a plan.

It can be easy to forget that the people make the place, because the structures that we create often outlive our memory of how and why we created them to begin with, leaving us feeling like we are the victims rather than the visionaries of the systems that we create. But over the long haul, one of the most powerful things that a company's leaders can do is to create a unique character and personality for their organization that fits their business environment and distinguishes them from the competition.

But where do you start? Research over the past two or three decades has shown that an organization's culture has an impact on business performance in four main ways:

- Creating an organization's sense of mission and direction

- Building a high level of adaptability and flexibility

- Nurturing the involvement and engagement of their people

- Providing a consistency that is strongly rooted in a set of core values

These are the cultural traits that most clearly affect business performance, so this is where the journey must begin.

But can something as complex as corporate culture actually be managed? The task is daunting—but doing nothing is not an attractive option! Organizational culture guru Edgar Schein said it best: “Either you manage the culture, or it manages you.”4 Managing culture change is certainly not easy, but there are plenty of real-life examples of global companies who have succeeded. This book is built around seven of those examples.

What Is Corporate Culture? Why Is It Important?

At the climax of the annual holiday party of one rapidly growing American company, hundreds of balloons are released from the ceiling. Inside each balloon is a crisp new US$100 bill. Whoever scrambles the hardest gets the most money! The lesson is simple, fun, and more powerful than all the personnel policy handbooks in the world. It helps capture the essence of some of the key definitions of corporate culture: Culture is both “the way we do things around here” and “what we do when we think no one is looking.” Culture is “the code, the core logic, the software of the mind that organizes the behavior of the people,” and “the lessons that we have learned that are important enough to pass on to the next generation.”5

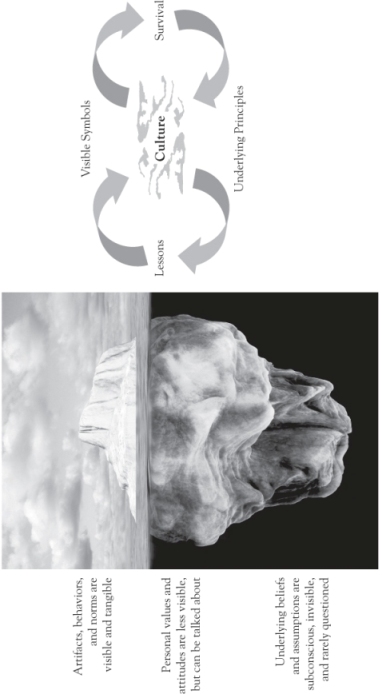

Schein's classic approach divides culture into three levels.6 He argues that basic underlying assumptions lie at the root of culture and are “unconscious, taken-for-granted beliefs, perceptions, thoughts, and feelings.” Espoused values are derived from the basic underlying assumptions and are the “espoused justifications of strategies, goals and philosophies.” Finally, at the top level are “artifacts,” defined as the “visible, yet hard to decipher organizational structures and processes.”

Consider the iceberg image presented in Figure 1.1. Only about 10 percent of an iceberg is visible above the water; 90 percent is below the surface. But the inertia of the part that is beneath the surface is what will sink your ship. Similarly, it is often the parts of the culture that we can't see that will get us into trouble. This figure also reminds us that the culture is learned—it is built up from the accumulated principles that we learn as we survive together over time. The lessons from the past shape our survival strategies for the future. Winston Churchill said something similar about architecture: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”7

Figure 1.1 Culture Reflects the Lessons Learned Over Time

So our mindset and worldview shape the way that we use the lessons of the past to forge the strategies of the future. How well are business leaders doing? Well, the record is not all that encouraging. Phil Rosenzweig's best seller The Halo Effect8 explains that when successful corporations become legends, their business practices are imitated for both good reasons and bad. Neither researchers nor executives have done particularly well at separating the principles and practices that truly impact business performance from those that are simply imitated because a corporation enjoyed great success and everyone now wants to be like them. Telling fashion from function is often harder than it looks.

There's a long tradition of studying “superstitious learning,” which probably has its roots in Malinowski's study of the “cargo cult” of the Trobriand Islanders in Papua New Guinea nearly one hundred years ago.9 Richard Feynman tells the story with an example from the end of World War II:

During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they've arranged to imitate things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he's the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They're doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn't work. No airplanes land.10

You may be thinking “Surely modern corporate ‘tribes’ must do far better at separating fact from fiction and deciding what really works than the ancient tribes of Papua New Guinea!” Well, let's not jump to conclusions. Many of the recent accounts of the subprime mortgage crisis emphasize the growing power of the system that was created.11 Mortgage loan officers made a bigger bonus if they booked more subprime loans. Fee income from new loans was high enough that even bad loans were good business for the banks. These government-guaranteed loans were sold to other banks, who created securities that were certified AAA grade. Investors around the world grabbed these up because they paid a higher rate of return. This system created an insatiable demand for banks to find even more prospective buyers who would borrow beyond their means in hopes of “flipping” their new home to take advantage of rising real estate prices before their balloon payment came due. This system paid off so well that in the short term everyone kept looking for the next deal long after the system had stopped paying off. Thus we see how ritual can become separated from reality even in the most sophisticated organizations.12

How Corporate Culture Impacts Business Performance

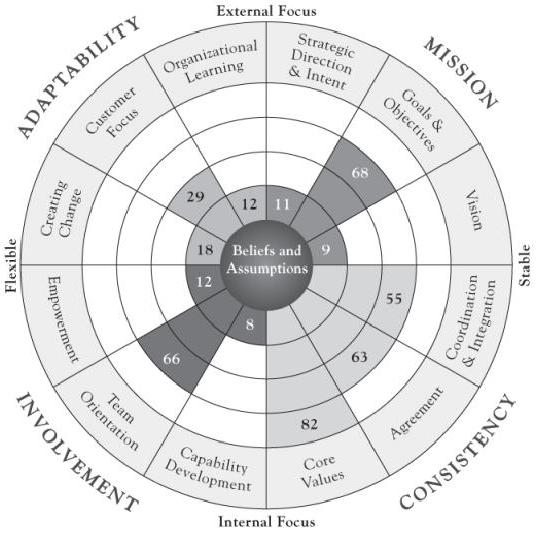

Over the past twenty years, we've studied the link between organizational culture and business performance. We've been trying to understand the cultural traits that explain the difference between high- and low-performing organizations.13 These studies have examined the link between the four basic traits in our model—mission, adaptability, involvement, and consistency—and performance measures such as profitability, sales growth, quality, innovation, and market value. Out of this research, we've developed a way to measure culture, and we've created a widely used Culture Survey designed to help organizations focus on the issues that need attention and move beyond a discussion of employee satisfaction, engagement, and morale, to better understand the actions they can take to build their organizations for the future. Figure 1.2 shows what we've found out about “What Counts.”

Figure 1.2 What Counts

•Mission. Successful organizations have a clear sense of purpose and direction that allows them to define organizational goals and strategies and to create a compelling vision of the organization's future. Leaders play a critical role in defining mission, but a mission can only be reached if it is well understood, top to bottom. A clear mission provides purpose and meaning by defining a compelling social role and a set of goals for the organization. We focus on three aspects of mission: strategic direction and intent, goals and objectives, and vision.

•Adaptability. A strong sense of purpose and direction must be complemented by a high degree of flexibility and responsiveness to the business environment. Organizations with a strong sense of purpose and direction often are the least adaptive and the most difficult to change. Adaptable organizations, in contrast, quickly translate the demands of the organizational environment into action. We focus on three dimensions of adaptability: creating change, customer focus, and organizational learning.

•Involvement. Effective organizations empower and engage their people, build their organization around teams, and develop human capability at all levels. Organizational members are highly committed to their work and feel a strong sense of engagement and ownership. People at all levels feel that they have input into the decisions that affect their work and feel that their work is directly connected to the goals of the organization. We focus on three characteristics of involvement: empowerment, team orientation, and capability development.

•Consistency. Organizations are most effective when they are consistent and well integrated. Behavior must be rooted in a set of core values, and people must be skilled at putting these values into action by reaching agreement while incorporating diverse points of view. These organizations have highly committed employees, a distinct method of doing business, a tendency to promote from within, and a clear set of do's and don'ts. This type of consistency is a powerful source of stability and internal integration. We focus on three consistency factors: core values, agreement, and coordination and integration.

Like many contemporary models of leadership and organizational effectiveness, this model focuses on a set of dynamic contradictions or tensions that must be managed.14 As Schein and others have noted, effective cultures always need to solve two problems at the same time: external adaptation and internal integration. Four tensions are highlighted by the model: the trade-off between stability and flexibility and the trade-off between internal and external focus are the basic underlying dimensions of the framework.15 In addition, the diagonal tensions between internal consistency and external adaptability, and the “top-down” versus “bottom-up” tension between mission and involvement exemplify some of the competing demands that organizations face.

For each of these dynamic contradictions, it is relatively easy to do one or the other, but much more difficult to do both. Organizations that are market focused and aggressive in pursuing every opportunity often have the most trouble with internal integration. Organizations that are extremely well integrated and controlled often have the hardest time focusing on the customer. Organizations with the most powerful top-down vision often find it difficult to focus on the bottom-up dynamics needed to implement that vision. Effective organizations, however, find a way to resolve these dynamic contradictions without relying on a simple trade-off. American novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald expressed the same concept when he said that “the test of a first rate intelligence is the ability to hold two contradictory ideas at the same time and still retain the capability to function.”16

At the core of this model we find underlying beliefs and assumptions. Although these deeper levels of organizational culture are difficult to measure, they provide the foundation from which behavior and action spring. Basic beliefs and assumptions about the organization and its people, the customer, the marketplace and the industry, and the basic value proposition of the firm create a tightly knit logic that holds the organization together. But when organizations are facing change or encountering new challenges from the competition, this core set of beliefs and assumptions, and the strategies and structures that are built on this foundation, come under fire. When that happens, the organizational system and the culture that holds it together need to be reexamined.

Some Real Examples

The concepts in this model were developed by listening to hundreds of stories from organizations large and small, public and private, old and new, successful and unsuccessful, all over the world. To illustrate how central these four traits are to real-world business success, let's now consider four well-known examples: IKEA, Apple, Ritz-Carlton, and Toyota.

IKEA: Mission Grows Out of Core Beliefs and Assumptions

IKEA founder Ingwar Kamprad grew up in the hardscrabble farmlands of southern Sweden and became an entrepreneur at an early age. By 1976, well established in the Swedish furniture business, he summarized his key principles of doing business in a little book called A Furniture Dealer's Testament.17 It is remarkable how many of the principles described in this book are still alive at IKEA over thirty years later.

Like most great organizations, Kamprad's company has not just produced profits but has also tried to serve a higher purpose in the world. IKEA brings style, value, and a better life to many. The company's products are designed for the global everyman, combining frugality, innovation, and style, using environmentally friendly materials. Everyone deserves the opportunity to be part of the IKEA revolution.

What is good for our customers is also, in the long run, good for us. This is an objective that carries obligations…. The objective must be to encompass the total home environment; that is, to offer furnishings and fittings for every part of the home whether indoors or outdoors…. It must reflect our way of thinking by being as simple and straightforward as we are ourselves. It must be durable and easy to live with. It must reflect an easier, more natural, and unconstrained way of life.18

In his book, Kamprad also expressed strong beliefs about how IKEA should operate, stressing the simplicity and self-reliance of an individual who today is worth over $30 billion but still counts every penny like it was his last. Consider his thoughts on simplicity:

Bureaucracy complicates and paralyzes! Exaggerated planning is the most common cause of corporate death. We do not need fancy cars, posh titles, tailor-made uniforms or other status symbols. We rely on our strength and our will.19

IKEA is a terrific example of how a global business strategy can grow from the core beliefs and assumptions of the founder. Consider just one key element of the IKEA system: the flatpack. As all loyal IKEA shoppers know, after following the one-way corridor through the store, looking at the kitchens and the bedrooms, and stopping at the restaurant for a coffee or light meal, you eventually make your way to checkout and finally pick up your purchases. They are all packed in flat boxes designed to take home and assemble yourself. You get the home entertainment at no extra charge!

Where did this brilliant strategic innovation come from? Was it the result of an expensive study from a leading consultancy? Or an outgrowth of a corporate innovation center designed to make IKEA more customer centric? No way!

In 1952, one of IKEA's first employees, Gillis Lundgren, had a problem. He was trying to load a table into his Volvo to deliver to a customer. It didn't fit. Gillis thought, “God, what a lot of space that takes up! Let's take the legs off and put them under the table top.”20 Voilà! Global strategy. The rest is just implementation. By 1956, this practice was standardized and has been an essential part of the IKEA experience ever since. The current system has continued to build on these key principles established in the early days.

IKEA's strong sense of mission and powerful corporate culture are not without their limitations. Growth has been steady, but relatively slow, especially given the dramatic enthusiasm of their customers. IKEA has never made much of an impact in the office furniture market, mostly because very few corporations want to assemble their own office furniture. Expanding to countries that are farther and farther away from their Swedish homeland has also presented some challenges. Successful franchisees who do like “fancy cars, posh titles, tailor-made uniforms, or other status symbols,” have also posed difficult choices for IKEA. But overall, “The IKEA Way” has been a central part of the fifty-year journey from an entrepreneur's dream to a global icon.

Apple: Adaptability Leads the Marketplace into the Future

Since Apple's founding in 1976 in a garage in Cupertino, California, its people have built their success around an unparalleled understanding of their customers' tacit needs. They deliver their technology to their customers in a way that shapes the customers' desires. Time and again, they have developed new products that their customers didn't really know they needed until they found out that they couldn't live without them. As cofounder Steve Jobs put it, Apple has focused their attention on developing “toys for yuppies,” while their competitors were often focused on the MHz of their new CPUs.21

A powerful recent example of Apple's genius in leading the marketplace is the App Store. It is a fascinating example of the competitive advantage created by adaptability. Building on their spectacular success with the iPod and iTunes, Apple set about developing the hardware and software to create another new market that didn't exist before: the smartphone and the App Store.

Nearly a half billion iPods later, it is hard to believe that ten years ago no one had ever heard of an iPod. A few of us downloaded digital music, but most of us were still carrying around CDs. But the iPod quickly became a necessity for people all over the world. Apple created a fundamental innovation in the way that music was delivered to consumers, building a new platform for revenue generation and innovation that would carry the firm far into the future. Apple was the intermediary between consumers and the music that they love.

This set the stage for Apple's entry into the smartphone business with the launch of the first iPhone in June 2007. The iPhone turned the iPod into a touchscreen cellphone with internet access. No longer would people need to carry a phone and an iPod and still find themselves in need of access to the internet to look up movie times or restaurant locations. Now it was all in the palm of their hand. And it was a big bet that the future of cellphones would be differentiated not by “radios and attennas and things like that,” but instead by software.22 The bet paid off handsomely—by Q4 2008 Apple surpassed BlackBerry maker Research in Motion to become the world's third largest phone maker, after Nokia and Samsung.

At first, developers created their own unsanctioned apps. But in March 2008, Apple released a software development kit to help developers create their own apps. They also created a radical set of rules for the App Store.23 It would cost developers $99 to submit an app, and they could charge whatever they wanted for downloads. Apple would retain 30 percent of the sale price for administration. The remaining 70 percent would go to the developer. If the app were offered for free, Apple would take no commission. Apple itself would maintain the App Store, control the approval process, and support the whole thing through iTunes.

The App Store was launched with five hundred apps in July 2008, to coincide with the global launch of the 3G iPhone in twenty-two countries. In the first year, nearly one hundred thousand apps were created, with two billion downloads to over twenty million iPhones worldwide. By the time that this book is published, there will be over one million apps. Apple now estimates that the App Store generates more than $1 billion each year.

Apple's approach to innovation is deeply rooted in their DNA. It has always been informed by a unique mindset that focuses on the ecosystem that surrounds their customers. Their innovations combine hardware and software with developers and consumers in ways that create revolutionary markets. The App Store connects the endless creativity of the developers with consumers' endless demand for software solutions, starting at a price point of $.99 or less and building from there. With Apple as the intermediary, Steve Jobs's legacy of innovation will be with us for a long time to come.

Ritz-Carlton Hotels: Involvement Creates Capacity

Ritz-Carlton hotels founder Cesar Ritz set the luxury standard for European hotels in the early twentieth century. He said, “Never say no when a client asks for something, even if they ask for the moon. You can always try.” Ritz-Carlton's “Three Steps of Service” set a high standard for five-star quality:

The Ritz-Carlton refers to their twenty-eight thousand people as “ladies and gentlemen, serving ladies and gentlemen.” Their remarkable core values are well understood by their people, starting with the “Employee Promise” and the “Credo.”

But perhaps the most remarkable part of all of this is what it takes to actually do this: every day, all of the Ritz-Carlton ladies and gentlemen participate in a daily briefing. All of their service people, in all of their hotels, meet to discuss the incidents that arose through the day, the actions that they took to address them, and how those fit with the Ritz-Carlton principles. This debrief is led by the local manager. The day's incidents and actions are also captured in their system so that they have a record of every guest's experience in each stay. That record can be used to anticipate and accommodate a guest's experience, even if it is at another Ritz-Carlton hotel. This allows the staff to achieve an unusual mark of distinction: they can create the same level of customer service for each of their clients at each hotel. The preferences that are established for a client at one hotel can be applied across the country or around the world at any time.

A friend of mine tells a story of going out for a run while staying at a Ritz-Carlton hotel. The first time, when he came back after the run, they asked him if he wanted something to drink. He asked for a bottle of water. The second time they had a bottle of water ready for him, and asked him if he preferred sparkling or still water! To his amazement, this knowledge of his personal habits and preferences followed him on to his next stay at another Ritz-Carlton hotel.

We usually associate high-involvement work practices with flat, democratic organizations with few levels and few status distinctions. But this is one part of the Ritz-Carlton culture that makes it an intriguing example: in order to thrive with a demanding clientele in a luxury segment of the market, they stake their claim on bottom-up input! And they do walk the talk: each of the “ladies and gentlemen” in their service operation has the authority to spend $2,500 on the spot to resolve a guest's concerns.

Some might argue that you can afford to lavish such attention on customers only when you are operating in a luxury segment of the market like the one that Ritz-Carlton serves.24 The average annual income of their guests is over $250,000, and nearly half of their guests are repeat visitors. Clearly, it is a big business decision to invest the time of both the managers and the staff in the daily debrief. But without this key part of the process, the good ideas would just remain good ideas. They wouldn't be put into action as the cornerstone of a time-tested competitive strategy that differentiates a Ritz-Carlton hotel from the rest of the pack in the luxury segment.

Toyota: Consistency Is the Foundation for Quality

Toyota was created by the Toyoda Automatic Loom Works in 1937 to produce automobiles. Their early history was one of difficult struggle, which required them to take advantage of every opportunity they could find to reduce waste and use resources efficiently. Toyota's culture grew organically for many years before the company attracted much attention. But by the 1980s, their world-class quality and conspicuous success led many to try to capture their essence and understand the huge leaps in competitive advantage that Toyota had made on the rest of the manufacturing world. Today, the Toyota Way is one of the most clearly articulated management philosophies in the world—there is probably more written about Toyota than about any other company, with the possible exception of General Electric.25 But, as many companies have found when trying to imitate the Toyota Production System, it is much easier to describe the Toyota mindset and culture than it is to copy it. To quote Toyota's former president, Fujio Cho:

The key to the Toyota Way and what makes Toyota stand out is not any of the individual elements. But what is important is having all the elements together as a system. It must be practiced every day in a very consistent manner, not in spurts.

We place highest value on actual implementation and taking action. There are many things one doesn't understand and therefore, we ask them, why don't you just go ahead and take action; try to do something? You realize how little you know and face your own failures and you simply can correct those failures and redo it again and at the second trial you realize another mistake or another thing you didn't like so you can redo it once again. So by constant improvement, or, should I say, the improvement based upon action, one can rise to the higher level of practice and knowledge.26

There are fourteen different elements to the Toyota Way that have been clearly articulated in many different sources. One of the key factors is the reliance on “pull” systems that avoid overproduction and force the organization and its supply chain to respond to the market demands. This helps them to create a continuous process flow that brings problems to the surface, levels out the workload, and forces them to stop to fix problems so that they can get quality right the first time. This approach is also extended to their partners and suppliers by challenging them and helping them improve.

Toyota's system has been built from their experience, over time. Toyota develops leaders who thoroughly understand the work and live the philosophy. They rely on “visual” controls so that no problems are hidden, and when there are problems, they encourage leaders to “go and see for themselves.” Finally, they base their management decisions on a long-term philosophy; they make decisions slowly through consensus but then implement them rapidly. They have led the way in their industry in resolving the dynamic paradox between internal consistency and external adaptability. They have done this by becoming a learning organization that has mastered relentless reflection and continuous improvement.

Each of these principles is significant in its own right and is a required part of the overall system. It is a system created to manage complexity in an efficient and predictable way through nearly flawless lateral coordination. Nonetheless, it can also be relatively simple once you develop the mindset that allows you to see the flow.27 “All we are doing is looking at the time line from the moment the customer gives us an order to the point when we collect the cash. And we are reducing that time line by removing the non-value-added wastes.”28

Toyota has successfully transplanted the logic and culture of their production system all over the world. This evolving philosophy has led Toyota from its original position as a struggling automaker in pre-war Japan to that of the largest and most profitable automotive company in the world. Moreover, Toyota manufacturing methods are imitated by nearly every manufacturer in the world in hopes of reaching the levels of quality and consistency defined by the leader.

But in early 2010, Toyota faced their biggest challenge in years. “Sudden acceleration” problems with Toyota vehicles in North America made headlines all over the world and compromised their reputation. Overnight, their stock price and sales dropped dramatically. Even though the technical issues that are at the heart of this problem have proven surprisingly difficult to establish, one strong lesson does emerge from this case: when your reputation is built on quality and consistency, it is absolutely necessary to protect and defend that characteristic in order to preserve and, as necessary, rebuild your brand. When we claim to live by our core values, people expect us to live up to them every day, without fail.

These examples—IKEA, Apple, Ritz-Carlton, and Toyota—were all chosen to illustrate the importance of the principles of mission, adaptability, involvement, and consistency. They are all remarkable success stories that show the power of these principles and help to illustrate what these principles mean in practical business terms.

Leading Culture Change in Global Organizations

This book tries to address a big void in the literature about culture and leadership in organizations: What happens when you try to change organizations? What works? What doesn't? Is it all chance and charisma? Or is it all process, methods, measures, and structure? Many authors have given us great principles for leading change in organizations.29 But very few have tried to systematically track what works and what doesn't so that we can learn more about how to create successful change in global organizations.

Again, we have built this book around a set of seven case studies from all over the world in which we have tracked organizations and their leaders over time, studied the changes that they have made, and tried to understand the impact that those changes have had on the business. For each organization, we analyzed “before and after” survey results to track the culture change. This assessment is a central part of this book, and we use this same approach in each chapter to track the progress that each organization is making. So let's take a minute to look at one brief example and learn how to interpret these profiles.

The four concepts in the culture model are measured through a sixty-item survey that produces a profile. This profile compares the results to a benchmark database of over a thousand organizations.30 These sixty items measure the four culture traits of mission, adaptability, involvement, and consistency. Each of these four traits is measured with three indexes, and each of those twelve indexes is measured using five survey items. This analysis helps to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the organization's culture and understand the impact that it may be having on business performance. For those with more interest in this survey and the research that supports it, we have included a detailed discussion in the Appendix, including an example that shows the sixty items that make up the twelve indexes.

The first rule for interpreting a culture profile is simple: more color is better. The scores on the profile show where the organization ranks relative to the benchmark. For example, a score of 9 on vision means that the organization ranks in the 9th percentile, telling them that 91 percent of the other companies in the benchmark database scored higher than they did on vision.

When the executive team of the One-Hundred-Year-Old Manufacturing Company looked at their results (see Figure 1.3), there was a long silence. The president, who had spent his career in operations, said, “Well, I admit that I'm not a visionary or a strategist—I'm the guy who makes the trains run on time.” When they focused on the results for consistency, they agreed that their emphasis on internal control made it difficult to react to the marketplace. They agreed that they had strong core values, but they also questioned whether they were the right core values for the future. One of them spoke up: “Our core values are perfectly suited for meeting the challenges of the 1980s.” Finally, when they looked at their results on team orientation, one of them concluded, “We're a team all right—we're all going down together!”

Figure 1.3 The One-Hundred-Year-Old Manufacturing Company

These results helped this leadership team see that the system they had created made it hard to innovate and grow, even though they still produced excellent quality products and were a good employer for many of their people. But the results also helped convince the leadership team that they were at the center of the problem and that their actions had to be at the center of any solution.

When confronted with this kind of result, most organizations that carry out successful changes go through a change process that looks something like the process depicted in Figure 1.4. The survey results help to identify the gaps and define what needs to change. But to drive action, an organization needs to build a team—a “guiding coalition,” in Harvard Professor John Kotter's terms—that will create a vision of the future, and define the actions and the accountabilities that will get them where they want to go.31 A commitment to tracking progress is also important in order to bring some accountability to the change process. As noted management consultant Ram Charan put it, “There's a fine line between vision and hallucination.”32 Tracking progress usually leads to another round of focused change. Each of the organizations that we studied for this book has gone through some variation of this general change process. We were involved with the change process in each of these organizations and will give you an overview of our role in each chapter.

Figure 1.4 Leading Culture Change

The Plan for This Book

This book is unique in that it is built around seven longitudinal case studies. We have followed the change process in each organization, and we have tracked that change process using “before-and-after” survey results over several years to help highlight some of the key lessons about leading culture change in global organizations. We start in Chapter Two by looking at the importance of supporting the frontline people in the organization, using the case of Domino's Pizza. Domino's presents an exciting story of the transition of a firm that had been led by its founder for nearly forty years, through a Bain Capital buyout, a new CEO, a successful IPO, and the implementation of a strategy based on people as the primary source of competitive advantage. Chapter Three turns to the topic of strategic alignment and uses the examples of two European organizations. First, the German technology company DeutscheTech shows us how a clear alignment of the purpose, vision, and strategy across organizational levels is critically important to the strategy implementation process. Chapter Three also examines the implementation of a crisis-driven top-down strategic change at Swiss Re's Americas Division. This example shows how changes that have a real impact on day-to-day work are the most likely to “stick” and to have a lasting effect. Chapter Four focuses on one of the most common topics in culture work: cultural integration in mergers and acquisitions. Although firms realize that it is hard to create scale without integration, they still struggle to get everyone around the world on the same page. This chapter focuses on Polar Bank, a Scandinavian bank trying to integrate three different acquisitions and make one culture out of many.

Chapter Five leads us to an even more complex topic: the exporting of culture change from the United States to Europe. GT Automotive, a UK-based firm, completes a successful transformation in their American division and then tries to export these changes back to their European organization. Chapter Six focuses on the challenge of building a global business in a developing market. We examine General Electric's efforts to build their health care business in China and then use that platform to build a global business. In our final case study, we focus on the challenges of creating a global corporation from a base in an emerging market by tracing the Brazilian mining company Vale in their ten-year journey from being a department in the Brazilian government to becoming a global player. In our final chapter, we summarize the key lessons for leaders about the magic and the method of these transformation stories. We discuss these lessons in terms of a new model of the rituals, habits, and routines that lie at the heart of their organizations' cultures.

Fasten your seat belts!

Notes

1 Guerrera, Francesco. “Wells Fargo Cracks the Whip.” Financial Times, August 24, 2008.

2 Gerstner, Louis V., Jr. Who Says Elephants Can't Dance? New York: HarperCollins, 2002.

3 Schneider, Benjamin. “The People Make the Place.” Personnel Psychology, no. 40 (1987): 437–453.

4 Schein, Edgar H. The Corporate Culture Survival Guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

5 Acknowledgments for definitions: “The way we do things around here” from Peters, Thomas J., and Waterman, Robert H., Jr. In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America's Best-Run Companies. New York: Warner Books, 1982; “What we do when we think no one is looking” from Bryan Adkins, personal communication, 2008; “The code, the core logic, the software of the mind that organizes the behavior of the people” from Hofstede, Geert, and Hofstede, Gert Jan. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005; “The lessons that we have learned that are important enough to pass on to the next generation” from Schein, Edgar H. Organizational Culture and Leadership (4th ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley, 2010.

6 Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership.

7 Churchill, Winston. House of Commons (meeting in the House of Lords). October 28, 1943. http://www.winstonchurchill.org/learn/speeches/quotations

8 Rosenzweig, Phil. The Halo Effect … and the Eight Other Business Delusions That Deceive Managers. New York: Free Press, 2007.

9 Malinowski, Bronislaw. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, 1922.

10 Feynman, Richard. Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! (Adventures of a Curious Character). New York: Norton, 1985, 340.

11 See, for example, Lewis, Michael. The Big Short. New York: Norton, 2010; McLean, Bethany, and Nocera, Joe. All the Devils Are Here. New York: Penguin Press, 2010.

12 See Weeks, John. Unpopular Culture. The Ritual of Complaint in a British Bank. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2004, for an insightful analysis of how the ritual of complaint can become detached from reality.

13 Denison, Daniel R. Corporate Culture and Organizational Effectiveness. New York: Wiley, 1990. Our research linking culture and effectiveness is also summarized in the Appendix.

14 Denison, Daniel R., Hooijberg, Robert, & Quinn, Robert E. “Paradox and Performance: a Theory of Behavioral Complexity in Leadership.” Organizational Science 6, no. 5 (1995): 524–540.

15 Lawrence, Paul R., and Lorsch, Jay W. Organization and Environment. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

16 Fitzgerald, F. Scott. “The Crack Up,” part one. Esquire, February 1936. http://www.esquire.com/features/the-crack-up

17 Kamprad, Ingvar. A Furniture Dealer's Testament. A Little IKEA Dictionary. Delft, Netherlands: Inter IKEA Systems B.V., 2007.

18 Ibid., p. 7.

19 Ibid., p. 14.

20 Jennings, Jason. Less Is More: How Great Companies Use Productivity as a Competitive Tool in Business. New York: Penguin Group, 2002, 16.

21 Schein, Edgar H. The Corporate Culture Survival Guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1999.

22 Wingfield, Nick. “iPhone Software Sales Take Off: Apple's Jobs.” Wall Street Journal, August 11, 2008, p.B1.

23 Krazit, Tom. “Apple Developers Mark a Year of iPhone Apps.” CNET News, March 5, 2009. http://news.cnet.com

24 The principles of mass customization practiced by Ritz-Carlton can also be applied in the lower end of the market. The citizenM Hotel at Amsterdam's Schiphol Airport, for example, does mass customization for free. When you are in your room, you have lots of choices for ambience: lighting, music, temperature, alarms, and so on. Click once and you have saved those choices in your profile so they are waiting for you on your next visit. Not quite The Ritz, but it is a lot cheaper.

25 Liker, Jeffrey. The Toyota Way. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

26 Ibid.

27 Rother, Mike, and Shook, John. Learning to See: Value-Stream Mapping to Create Value and Eliminate MUDA. Cambridge, MA: Lean Enterprise Institute, 2003.

28 Ohno, Taiichi. Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production. Tokyo: Diamond, 1978.

29 Collins, Jim. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap… and Others Don't. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

30 Denison, Daniel R., and Uehara, Ken. “Denison Organizational Culture Survey: Overview of 2011 Normative Database.” Denison Consulting, August 2011.

31 Kotter, John P. Leading Change. Boston: Harvard Business Press, 1996.

32 Charan, Ram. Leadership in the Era of Economic Uncertainty: The New Rules for Getting the Right Things Done in Difficult Times. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008.