3.10 The Dodd–Frank Executive Compensation Reform Act (2010–2011)

In July 2010, President Obama signed into law the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act or Dodd–Frank Act, which was the culmination of the President and Congress’s controversial and wide-ranging efforts to regulate the financial services industry. In spite of its enormous length—the bill itself spans 848 pages—the Act leaves most of the details to be promulgated by a variety of government entities. Indeed, attorneys at DavisPolk (2010) calculate that the Act requires regulators from at least nine agencies to create 243 new rules, conduct 67 studies, and issue 22 periodic reports.

3.10.1 Pay Restrictions for Financial Institutions

While the pay restrictions in the TARP legislation apply only to banks receiving government assistance, the Dodd–Frank Act goes much further by regulating pay for all financial institutions (public or private, TARP recipients and non-recipients) including broker-dealers, commercial banks, investment banks, credit unions, savings associations, domestic branches of foreign banks, and investment advisors. Specifically, Part (a) of Section 956 of the Dodd–Frank Act requires all financial institutions to identify and disclose (to their relevant regulator) any incentive-based compensation arrangements that could lead to material financial loss to the covered financial institution, or that provides an executive officer, employee, director, or principal shareholder of the covered financial institution with excessive compensation, fees, or benefits. In addition, Part (b) of Section 956 of the Dodd–Frank Act prohibits financial institutions from adopting any incentive plan that regulators determine encourages inappropriate risks by covered financial institutions, by (1) providing an executive officer, employee, director, or principal shareholder of the covered financial institution with excessive compensation, fees, or benefits; or (2) that could lead to material financial loss to the covered financial institution.

Since at least the early 1990s, there has always been a tension between shareholders (the firm’s legal owners) concerned about CEO incentives, and uninvited guests (such as politicians and labor unions) concerned about high levels of pay. After the TARP bailouts in the financial crisis, the analogous tension was between taxpayers (who wanted to be protected from excessive risks while receiving an appropriate return on their investment) and politicians who were outraged about perceived excesses in banking bonuses. Section 956(b) of the Dodd–Frank Act deliberately conflates these tensions, by explicitly defining excessive compensation as an inappropriate risk. Moreover, Section 956(a) of the Dodd–Frank Act requires banks to inform their regulators of compensation plans that provide excessive compensation, delegating to the regulators the Herculean task of defining what compensation is excessive (or, indeed, which risks are inappropriate).

The responsibility for implementing Section 956 of the Dodd–Frank Act fell jointly to seven agencies: the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the Federal Reserve System, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Office of Thrift Supervision, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the National Credit Union Administration, and the Federal Housing Finance Agency. In March 2011, the seven agencies issued a joint proposal for public comment, modeled in part on Section 39 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Act. While the proposal stops short of explicitly limiting the level of executive compensation, it prohibits compensation that is unreasonable or disproportionate to the amount, nature, quality, and scope of services performed. In addition, the proposal calls for firms to identify individuals who have the ability the expose the firm to substantial risk, and demands that (for the larger institutions) such individuals have at least 50% of their bonuses deferred for at least three years; deferred amounts would be subject to forfeiture if subsequent performance deteriorates. Final rules were expected in late 2012.

3.10.2 Pay and Governance Reforms for all Publicly Traded Companies

While ostensibly focused on regulating firms in the financial services industry, the authors of the Dodd–Frank Act seized the opportunity to pass a sweeping reform of executive compensation and corporate governance imposed on all large publicly traded firms across all industries. The new rules include:

Say-on-Pay (Section 951). Shareholders will be asked to approve the company’s executive compensation practices in a non-binding vote occurring at least every three years (with an additional vote the first year and every six years thereafter to determine whether the Say-on-Pay votes will occur every one, two, or three years). In addition, companies are required to disclose, and shareholders are asked to approve (again, in a non-binding vote), any golden parachute payments in connection with mergers, tender offers, or going-private transactions.

In January 2011 – and effective for the 2011 proxy season – the SEC adopted rules concerning shareholder approval of executive compensation and “golden parachute” compensation arrangements. Shareholders of 98.5% of the 2532 companies reporting 2011 results by July 2011 approved the pay plans; over 70% of the companies received more than 90% favorable support.143Similarly, shareholders of 98.2% of the 1875 companies reporting 2012 results by June 2012 approved the pay plans; 72% of the companies received more than 90% favorable support.144Twenty six of the 30 companies receiving less than 50% positive votes in 2011 passed in 2012, and year-over-year favorable votes increased by 14% for companies receiving between 50% and 70% favorable votes in 2011.

Clawbacks (Section 954).

Companies must implement and report policies for recouping payments to executive based on financial statements that are subsequently restated. The rule applies to any current or former executive officer (an expansion of Sarbanes-Oxley, where only the CEO and CFO were subject to clawbacks), and applies to any payments made in the three-year period preceding the restatement (Sarbanes-Oxley only applied for the twelve months following the filing of the inaccurate statement).

The SEC had neither adopted nor proposed rules regarding the recovery of executive compensation by August 2012. However, Equilar reports that 86% of the Fortune 100 companies issuing proxy statements in 2012 had publicly disclosed clawback arrangements; in half of the companies the clawback triggers were related to financial restatements and ethical misconduct.145

Additional Disclosures (Sections 953, 955, 972).

Companies must report the ratio of CEO compensation to the median pay for all other company employees. Companies must analyze and report the relation between realized compensation and the firms financial performance, including stock-price performance. In addition, companies must disclose its policies regarding hedging by employees to protect against reductions in company stock prices. Finally, the Dodd–Frank Act requires companies to disclose their policies and practices on why the company chooses either to separate the Chairman and CEO positions, or combine both roles.

The SEC had neither adopted nor proposed rules regarding the disclosure of pay ratios, pay-for-performance, hedging and CEO/Chair combinations by August 2012.

Compensation Committee Independence (Section 952).

Following Sarbanes-Oxley (2002) requirements for Audit Committees, publicly traded companies are required to have compensation committees comprised solely of outside independent directors (where independence takes into account any financial ties the outside directors might have with the firm. In addition, companies must assess the independence of compensation consultants, attorneys, accountants, and other advisors to the compensation committees.

In June 2012, the SEC adopted final rules directing exchanges to establish listing standards guaranteeing that members of the compensation committee (or directors who oversee executive compensation matters in the absence of a committee) to be independent. While leaving the precise definition of “independence” to the exchanges, the final rule required exchanges to consider the director’s source of compensation (including consulting or advisory fees) paid by the issuer, and whether the director is affiliated with the issuer, a subsidiary of the issuer, or an affiliate of a subsidiary of the issuer.

In addition, the new SEC rules require firms to ensure that compensation committees have authority and funding to retain compensation consultants. While neither the Act nor the June 2012 Final Rule issued by the SEC required compensation advisors to be independent, the SEC imposed a list of independence criteria that boards must consider in retaining a consultant. Finally, proxy statements issued in connection with annual shareholder meetings in 2013 and after must disclose whether the work of the consultant has raised any conflict if interest and, if so, the nature of the conflict and how the conflict is being addressed.

Proxy Access (Section 971).

The Dodd–Frank Act authorized the SEC to issue rules allowing certain shareholders to nominate their own director candidates in the company’s annual proxy statements.

The SEC issued its rules on Proxy Access in August 2010, but delayed implementation after lawsuits by the Business Roundtable and the US Chamber of Commerce claimed that the rules would distract management and advance special-interest agendas. In July 2011, the US Circuit Court of Appeals (Washington, DC) ruled in favor of the business groups and rejected the SEC’s rule. As of August 2012, the SEC had not announced whether it would attempt to rewrite the rule in a way that would be acceptable to the Court.

It is too early to assess the ultimate effect of Dodd–Frank on executive compensation, since many of the rules have just been implemented or are still being written. However, based on experiences with similar rules, I can speculate on the ultimate impact.

Say on Pay. In mandating Say-on-Pay, the Dodd–Frank Act follows similar rulings for non-binding shareholder votes enacted in the United Kingdom in 2002 and later in Australia, Denmark, France, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden; the Netherlands and Norway went a step further by allowing binding shareholder votes. Say-on-Pay had long been a favorite objective of Democrats in Congress, and the Say-on-Pay Bill passed the House in April 2007 by a 2:1 margin. While the companion bill introduced in the Senate by then-Senator Obama was shelved prior to a vote, Say-on-Pay was widely expected to become law following the 2008 presidential election, especially after Say-on-Pay was mandated for TARP recipients as part of the Dodd Amendments.

In spite of the support, however, there is modest evidence that Say-on-Pay results in important changes to compensation practices. In the United Kingdom (where we have the most data), there is some evidence that negative Say-on-Pay votes have led to some reductions in salary continuation periods in severance agreements and some changes in performance-based vesting conditions in equity plans, but no evidence that the votes have affected compensation levels (Ferri and Maber, 2010). In the United States, where shareholders voted on the compensation for TARP executives for the first time in early 2009, the plans were passed at all firms, with an average of 88.6% of the votes cast in favor of management. Among the TARP recipients garnering the strongest support were the Wall Street firms whose compensation systems allegedly fostered the financial crisis, including Goldman Sachs (98%), AIG (98%), JPMorgan (97%), Morgan Stanley (94%), Citigroup (84%), and Bank of America (71%).146

As emphasized in this chapter, regulation inevitably produces unintended consequences. The most obvious (and most negative) unintended consequence associated with Say-on-Pay reflects the increasing influence of proxy-advisory firms (primarily Institutional Shareholder Service (ISS)). To fulfill their required fiduciary duties to vote proxies, institutional investors routinely rely on ISS and other proxy-advisory firms for recommendations on how to vote on Say-on-Pay and other proxy matters. In turn, the proxy-advisory firms rely on a limited (and controversial) set of quantitative criteria to determine whether to offer positive or negative voting recommendations.147 In a broad sample of Russell 3000 firms, Larcker, McCall, and Ormazabal (2012) show: (1) the recommendations of the proxy-advisory firms do, indeed, affect voting outcomes; (2) anticipating this result, firms change their compensation policies to avoid negative recommendations; and (3) the market reaction to these changes is statistically negative.

Firms inherently face different competitive and incentive challenges, and there is neither a “one-size-fits-all” solution to these challenges, nor a limited set of quantitative criteria that can substitute for a careful and holistic assessment of compensation plans that takes into account company-specific situations and objectives. Ultimately, the benefits of adhering to the ISS criteria must be weighed against the cost associated with reduced innovation and flexibility in the provision of compensation and incentives.

Compensation Committee and Advisor Independence. The Dodd–Frank provisions on the independence of the compensation committee will have little practical effect for large companies, since the listing requirements of the NYSE and NASDAQ have required independent compensation committees since 2003, and the IRS has required independent compensation committees (for Section 162(m) purposes) since 1994. The provision related to the independence of compensation consultants, in combination with SEC disclosure rules introduced in December 2009, will encourage more committees to retain their own independent consultant in addition to the consultants engaged by management.148

Clawback Provisions. The Sarbanes-Oxley experience shows that companies rarely try to recover erroneously awarded compensation from their CEO and CFO, often citing potential litigation costs and the feasibility of recouping money that has already been paid and taxed. The Dodd–Frank provision makes it more difficult for boards to shirk their responsibility to recovery erroneously awarded pay, and indeed likely subjects boards to shareholder litigation if they fail to even try.

Ratio of CEO-to-Worker Pay. The most mischievous and controversial compensation provision in Dodd–Frank is the required disclosure of the ratio of CEO pay to the median pay of all employees. The calculation costs alone can be immense for large multinational or multi-segment corporations where payroll is decentralized: to compute the median the company needs an often non-existent single compensation database with all employees worldwide. More importantly, however, is what shareholders are supposed to do with this new information, or how they should determine whether a ratio is too high or too low. Ultimately, this provision reflects a belief in Congress that CEO pay is excessive and its sole purpose is the hope that disclosing the ratio will shame boards into lowering CEO pay.

Proxy Access. Finally, potentially most important is the Proxy Access rule allowing shareholders to include their director nominees on the proxy alongside with the board’s nominees. In issuing its rule in August 2010, the SEC limited access to shareholders who have held at least 3% of the company’s stock for at least three years. One view is that Proxy Access will provide shareholders with a critical mechanism to replace poor directors with better ones. A more-cynical view—expressed by the Wall Street Journal and others—is that 3% was chosen as the sweet spot for labor unions and other politically motivated organizations who will use their leverage over the proxy statement to force companies to support political causes rather than increasing shareholder value.149 In its July 2011 ruling rejecting the SEC’s rule, the US Circuit Court of Appeals (Washington, DC) issued a sharp rebuke to the SEC, saying that the SEC failed in analyzing the cost the rule imposes on companies and in supporting its claim that the rule would improve shareholder value and board performance.150

4 International Comparisons: Are US CEOs Still Paid More?

4.1 The US Pay Premium: What We Thought We Knew151

Among the best-known “stylized facts” about executive compensation is that CEOs in the United States are paid significantly more than similarly situated CEOs in foreign corporations (e.g. Abowd and Bognanno, 1995; Abowd and Kaplan, 1999; Murphy, 1999). However—although widely accepted by academics, regulators, and the media—this stylized fact has not generally been based on consistent and comprehensive pay data across a large number of countries with controls for cross-country differences in firm characteristics. In particular, while the United States has required detailed disclosures on executive compensation since the 1930s, the majority of other countries have historically required reporting (at most) the aggregate cash compensation for the top-management team, with no individual data and little information on the prevalence of equity or option grants.

In fact, prior to 2000, only Canada (which mandated pay disclosures in 1993) and the United Kingdom (based on disclosure recommendations issued in 1995) required US-style full disclosure of CEO compensation (including details on equity grants). Based on data from 1993 to 1995, Zhou (2000) shows that US CEOs earned more than double their Canadian counterparts. Conyon and Murphy (2000) show that US CEOs earned almost 200% more than British CEOs in 1997, after controlling for industry, firm size, and a variety of firm and individual characteristics. Conyon, Core, and Guay (2011) show that the US versus UK Pay Premium had fallen to 40% by 2003 and plausibly disappears after adjusting for the risk associated equity-based compensation.

Other multi-country pay comparisons have typically relied on aggregate or average executive pay across groups of executives, usually excluding equity-based pay).152 For example, Conyon and Schwalbach (2000)’s comparison of UK and German compensation from 1968 to 1994 focused on only cash compensation for the United Kingdom (because the study predated the UK recommendations on disclosing stock options) and average cash compensation for Germany (because German rules required only disclosing the total cash paid across the group of top managers). Similarly, Muslu (2008)’s study of the largest 158 European companies from 1999 to 2004 (based on hand-collected annual reports) presents a mixture of individual and aggregated compensation data. Bryan, Nash, and Patel (2006) relied on SEC Form 20-F filings from 1994 to 2004 for foreign companies cross listing in the United States; however, cross-listed companies are only required to disclose compensation for individual executives if such disclosure is required in the home country, and as a result most of their analysis was based on average compensation for the management group.

Beyond the comparisons with Canada and the United Kingdom, and the handful of studies based on aggregate cash compensation data, much of what we know (or thought we knew) about international differences in CEO pay has been based on Towers Perrin’s biennial Worldwide Total Remuneration reports, utilized (for example) by Abowd and Bognanno (1995), Abowd and Kaplan (1999), Murphy (1999), and Thomas (2008) (not coincidentally, the same cites as in the first paragraph). These international comparisons—which have typically suggested that US CEOs are paid more than twice the “going rate” for CEOs in other countries—are not based on “data” per se, but rather depict the consulting company’s estimates of “typical” or “competitive” pay for a representative CEO in an industrial company with an assumed amount in annual revenues, based on questionnaires sent to consultants in each country. While crudely controlling for industry and firm size (by design), it is impossible using these surveys to control for other factors that might explain the US “pay premium”, such as ownership and board structure or individual CEO characteristics.

The disclosure situation has improved markedly over the past decade. Regulations mandating disclosure of executive pay were introduced in Ireland and South Africa in 2000 and in Australia in 2004. In May 2003, the European Union (EU) Commission issued an “Action Plan” recommending that all listed companies in the EU report details on individual compensation packages, and that EU member countries pass rules requiring such disclosure. By 2006, six EU members (in addition to the United Kingdom and Ireland) had mandated disclosure: Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, and Sweden. In addition, although not in the EU, Norway also adopted EU-style disclosure rules, and Switzerland demanded similar disclosure for the “highest-paid” executive.

4.2 New International Evidence

In my joint work with Nuno Fernandes, Miguel Ferreira and Pedro Matos (Fernandes et al., 2012)—based on recently available data from 14 countries with mandatory pay disclosures—we show that the stylized fact that US CEOs earn substantially more than foreign CEOs is wrong, or at least outdated. In particular, we show that the “US Pay Premium” became statistically insignificant by 2007 and largely reflects a risk premium for stock-option compensation (which remains more prevalent in the United States than in other countries).

In reaching our conclusion that the US Pay Premium has become modest (or insignificant), we control not only for the “usual” firm-specific characteristics (e.g. industry, firm size, volatility, and performance) but also for governance characteristics that systematically differ across countries: ownership and board structure. Compared to non-US firms, US firms tend to have higher institutional ownership and more independent boards, factors associated with both higher pay and increased use of equity-based compensation. In addition, shareholdings in US firms tend to be less dominated by “insiders” (such as large-block family shareholders), factors associated with lower pay and reduced use of equity-based compensation.

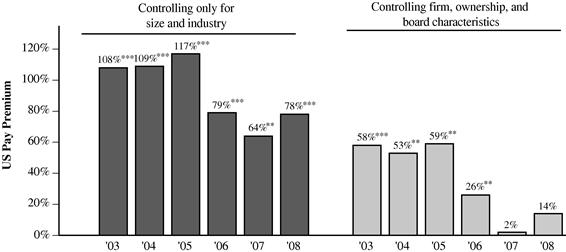

Figure 23 traces the evolution of the US pay premium from 2003 to 2008 (based on results in Table 8 of Fernandes et al., 2013). The premium is defined as eβ1 − 1 in the following regression, estimated annually for a pooled sample of US and non-US CEOs:

![]()

Figure 23 The evolving (and disappearing) US Pay Premium. Note: The figure shows the US Pay Premium implied by regression Ln(CEO Pay) on a US dummy variable plus controls for industry and company revenues (left-hand panel) and also other firm characteristics, ownership structure, and board structure (right-hand panel) for each year from 2003 to 2008. ***, **, * indicates that the coefficient on the US premium on each underlying regression depicted above is significant at the 1, 5, and 10% levels, respectively. Source: Fernandes et al. (2013), Table 8.

The sample consists of between 1426 and 1532 US firms and between 781 and 1480 non-US firms per year. US data are extracted from ExecuComp, while non-US data are based primarily on BoardEx and supplemented with hand-collected data from filings.

The “Firm Characteristics” in the left-hand panel of Figure 23 include only controls for company size (Ln(Revenues)) and industry (fixed effects for 12 Fama-French industries). As shown in the figure, the implied US Pay Premium fell significantly from over 100% in 2003–2005 to less than 80% in 2006–2008. The right-hand panel includes additional controls for leverage, Tobin’s Q, stock volatility, stock returns, ownership structure (the fraction of shares held by insiders and institutions) and board structure (board size, independence, the average number of board positions held by each board member, and a dummy variable indicating that the CEO also holds the title of Chairman). As shown in the figure—after including these additional controls—the implied US Pay Premium declined from nearly 60% in 2003 to only 26% in 2006 and 2% in 2007.

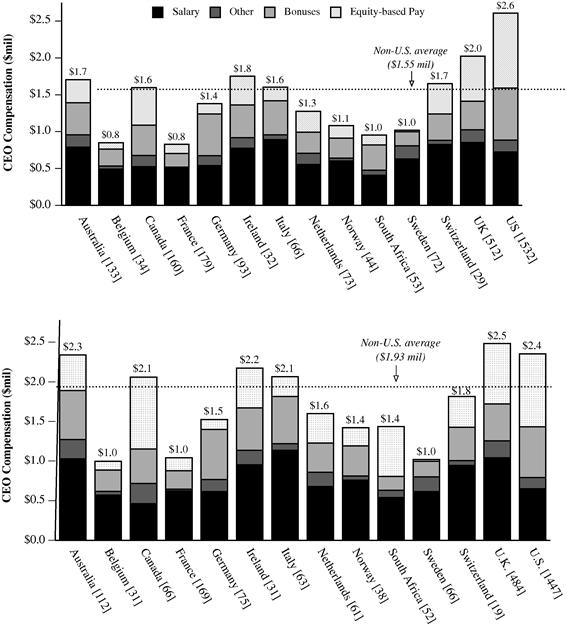

Figure 24 shows the international distribution of predicted 2006 CEO pay for a hypothetical firm with $1 billion sales, based on the specification used for Figure 23 with the “US dummy” replaced by a set of 14 country dummies. Panel A, in the spirit of the Towers Perrin estimates, controls only for firm size and industry, while Panel B controls for industry, firm characteristics, ownership, and board characteristics. The pay composition percentages are defined as the average composition across all CEOs for each country. The figure shows that US CEOs earn substantially more than non-US CEOs controlling only for size and industry. However, after controlling for firm, ownership, and board characteristics, we find effective parity in CEO pay levels among Anglo-Saxon nations (United States, United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, and Canada) and also Italy.

Figure 24 2006 CEO pay after controlling for firm characteristics, ownership, and board structure Panel A. Controlling only for sales and industry Panel B. Controlling for sales, industry, and firm, ownership, and board characteristics Note: The figure compares 2006 CEO pay in each country controlling for firm size (sales) and industry in Panel A, and controlling for size, industry, and firm, ownership, and board characteristics in Panel B. We regress the logarithm of total compensation on the logarithm of sales and 12 industry and 14 country dummies. For each country, we estimate the pay for a CEO running a hypothetical firm with $1 billion in sales using the estimated coefficient for pay-size sensitivity and controlling for the “average” industry. The non- US average is weighted by the number of firms in each country. The pay composition percentages are defined as the average composition across all CEOs for each country. Source:Fernandes, et al. (2013), Figure 1.

As an extension to the results in Figures 23 and 24, we also compare international differences in risk-adjusted pay, using methodologies similar to that used above in Section 2.1.2 and Figure 7.153 Consistent with the conclusions of Conyon et al. (2013) (who use a different methodology and consider only US–UK comparisons), we find that the risk-adjusted US pay premium for 2006 is statistically insignificant after controlling for governance (but remains significant before such controls), and that risk-adjusted pay in the US is significantly less than CEO pay in the United Kingdom and Australia, and insignificantly different from CEO pay in Canada, Italy and Ireland.

In addition, we show that both the level and structure of 2006 pay for US CEOs is insignificantly different from that of non-US CEOs of “internationalized” firms, which we define as firms above the 75th percentile ranked by foreign institutional ownership, foreign sales (as a fraction of total sales), or board international diversity (defined as the number of different nationalities represented on the board of directors divided by the total board size). We also find insignificant differences between US CEOs and non-US CEOs in firms included in the 1500-firm Morgan Stanley Capital International All Country World Index (routinely used as a benchmark for global equity mutual funds and used here as a proxy for foreign investor demand).

Finally, we find no significant differences in the level or structure of pay when US CEOs are compared to non-US CEOs of “Americanized” firms, which we define as firms cross-listed on US exchanges (as a proxy for demand by US investors) or above the 75th percentile ranked by US institutional ownership, total acquisitions of US companies between 1996–2005 (as a proxy for exposure to US product and labor markets), and the fraction of directors who also sit on boards of companies headquartered in the United States (as a proxy for exposure to US pay practices).

Overall, our evidence is inconsistent with the view that US CEO pay is “excessive” when compared to that of their foreign counterparts, but rather reflects tighter links between CEO pay and shareholder performance in US firms. First, we show that the US pay premium is modest after controlling for firm, ownership, board, and CEO characteristics. Second, we demonstrate that it is misleading to examine cross-sectional or cross-country differences in the level of pay in isolation, without also examining differences in the structure of pay, namely the use of equity-based compensation. In fact, the firm, ownership, and board characteristics associated with higher pay are those associated with a larger fraction of equity-based pay. Third, we find that CEO pay levels and the use of equity-based compensation are positively related to variables routinely used as proxies for better monitoring and better governance, namely institutional ownership and board independence. Fourth, our findings suggest that the observed US CEO pay premium reflects compensating differentials for the equity-based pay increasingly demanded by internationally diverse boards and shareholders. We find evidence that foreign and US institutional shareholders are linked to a greater use of equity-based pay and higher pay levels in non-US firms in which they invest. Finally, the convergence of US and non-US CEO pay levels since 2003 seems to be explained by the convergence of ownership structures and globalization of capital markets.

4.3 Why do US CEOs Receive More Options?

Our finding that the US pay premium largely disappears after controlling for the relative riskiness of US pay packages potentially “explains” the pay differences but naturally leads to another question: Why do US executives receive more equity-based compensation than their foreign counterparts?

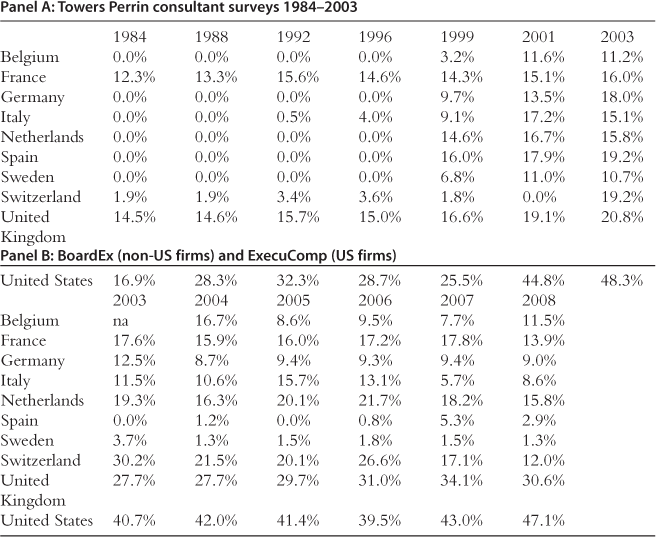

While equity-based compensation has been a staple of US compensation contracts for more than a half-century, the use of equity-based pay outside the United States is a relatively recent phenomenon. Panel A ofTable 3 shows how the importance of equity-based pay has changed over time in the United States and in nine European countries using Towers Perrin’s Worldwide Total Remuneration (WWTR) surveys for the selected years 1984, 1988, 1992, 1996, 1999, 2001, and 2003. The data for the years 1992–1996 are based on the Abowd and Kaplan (1999) analysis of the WWTR surveys. As shown in Panel A, only France and the UK made extensive use of stock or options in the 1980s, and equity-based pay did not become common across Europe until the end of the 1990s. By 2003, Towers Perrin reports that equity-based pay accounts for between 10% and 20% of competitive pay for European CEOs, and for about half the pay of American CEOs.

Table 3 Stock-based pay (as a percentage of total pay) in Europe and the United States

Note: Data in Panel A are from Towers Perrin’s Worldwide Total Remuneration reports (various issues), including 1984–1992 data reported by Abowd and Kaplan (1999). Data reflects Towers Perrin’s estimate of competitive CEO pay for industrial companies with approximately US $300 million in annual revenues. Stock-based pay includes the grant-date expected value of option grants and annualized targets from performance share plans. Data in Panel B are from BoardEx and ExecuComp. The percentages in Panel B are constructed by first computing the average ratio of equity-based pay to total compensation for each CEO, and then averaging across CEOs.

As discussed earlier, the data in Panel A of Table 3 are not CEO pay “data” per se, but rather consulting company’s estimates of “typical” or “competitive” pay for a representative CEO in an industrial company, based on questionnaires sent to consultants in each country. In Panel B of Table 3, I provide my own estimates of equity-based pay for 2003–2008 based on actual grant-date values extracted from BoardEx (for Europe) and ExecuComp (for the United States). The actual averages for 2003 in Panel B are generally consistent with the consultant surveys in Panel A for the same year, increasing my confidence in both data sources. As shown in Panel B, the use of equity-based compensation has generally declined in continental Europe between 2003 and 2008, and has remained relatively constant in the United Kingdom at just under a third of total compensation. In contrast, the use of equity-based pay has increased in the United States.

Traditional agency theory suggests a finite number of factors that might explain a greater use of incentive-based pay among US executives. First, US CEOs may be less risk averse or have steeper marginal costs of effort than their non-US counterparts, but to our knowledge there is no theory or empirical work suggesting such international differences in risk-aversion coefficients. Second, performance of non-US firms might be measured with substantially more noise than for US firms, leading to lower pay-performance sensitivities and lower expected levels of pay. However, we find no evidence that cash flows or shareholder returns are systematically more variable in our sample of non- US firms than in US firms. Extensions of the traditional model to incorporate differences in both ability and in the marginal productivity of CEO effort might help reconcile the data, but only given the additional assumptions that executives are more able and more productive in the United States. Overall, there are no compelling agency-theoretic explanations for the relative reliance on equity-based compensation in the United States.154

In unreported analysis, we attempt to explain international differences in the use of equity-based compensation by a variety of country-level variables routinely used in international studies of corporate governance to measure differences in the economic, law, and institutional environment of each country.155 We find that CEO equity-based pay (and total pay) is more prevalent in common-law countries (La Porta et al., 1998) which in turn is largely defined by the United Kingdom and its former colonies, including (in our sample) Australia, Canada, Ireland, South Africa, and the United States, and countries with stronger investor protections and private control of self-dealing (Djankov et al., 2008). We also consider different aspects of a country’s regulatory environment. We find a positive association between CEO equity-based pay and the levels of compensation disclosure and director liability (La Porta, Lopez-De-Silanes, and Shleifer, 2006); note that the United States scores high in both indices. We find that equity-based pay is lower in countries with friendlier collective labor laws and countries where labor unions are more powerful (Botero et al., 2004), such as in Continental European countries (e.g. France and Germany). In contrast, differences in CEO pay are not explained by GDP per capita levels.

Ultimately, the cross-country differences in the prevalence of equity-based compensation may be driven by idiosyncratic events that in some cases encouraged, and in others discouraged, the use of stock options and restricted stock. For example, as documented in Section 3, America’s reliance on stock options as the primary form of long-term compensation began in the 1950s as a result of tax policies designed to promote options, and declined in the late 1960s when the government reduced tax benefits. The early 1990s created a “perfect storm” for an explosion of option grants for not only executives but also lower-level managers and employees. The explosion in option grants continued unabated until the burst of the Internet bubble in 2000, followed by a series of accounting scandals that re-focused attention on the accounting treatment of options. Eventually, FASB mandated expensing, and companies moved away from options toward restricted stock.

Conyon et al. (2013) provide an analogous description of the evolution of equity-based pay in Europe. For example, the widespread adoption of stock-option plans in Europe initially emerged as governments provided tax incentives to encourage their use in the United Kingdom (in 1982), France (1984), and Italy (1998). Controversies in the United Kingdom in the 1990s involving perceived option excesses at recently privatized utilities led to a shift from options to restricted stock; concerns over excessive executive pay led France to revoke its tax subsidies on options in 1995, and Italy to revoke its tax subsidies in 2006. In Germany, option plans were not even legalized until 1996, and were still challenged in a series of high-profile lawsuits brought by a maverick college professor. In 1999, the Spanish government increased taxes on stock options after it was revealed that the CEO of the recently privatized telephone company was about to make a fortune exercising options.

In each country, ebbs and flows in option grants followed government intervention, usually reflecting tax or accounting policies and often reactions to isolated events or situations. Since the triggering events vary across countries, the nature of the government intervention—and the subsequent use of stock options—has also varied. The “perfect storm” that triggered the US option explosion (i.e. the “six factors” explored in Section 3.7 above) has not been repeated elsewhere in the world, and therefore the use of options (and equity-based pay in general) continues to be much higher in the United States.

5 Towards a General Theory of Executive Compensation

The academic literature focused on explaining cross-sectional differences and time-series trends in executive compensation is roughly divided into two camps: the “efficient contracting” camp and the “managerial power” camp. The efficient contracting camp maintains that the observed level and composition of compensation reflects a competitive equilibrium in the market for managerial talent, and that incentives are structured to optimize firm value. The managerial-power camp maintains that both the level and composition of pay are determined not by competitive market forces but rather by powerful CEOs, often working through or influencing captive board members. Most papers in the literature have adopted one approach or the other (often implicitly), and an increasing number of papers have treated the two approaches as competing hypotheses, attempting to distinguish between them empirically.

Ultimately, viewing efficient contracting and managerial power as competing hypotheses to “explain” executive compensation has not been productive. First, the hypotheses are not mutually exclusive; indeed, the same institutions that have evolved to mitigate conflicts of interest between managers and shareholders (i.e. efficient contracting) have simultaneously allowed executives to extract rents (i.e. managerial power). For example, the first “line of defense” against agency problems are the outside members of the board of directors, elected by shareholders and responsible for monitoring, hiring, firing, and setting top-executive compensation. However, these outside board members—who pay executives with shareholder money and not their own—are in no sense perfect agents for the shareholders who elected them. Instead of viewing efficient contracting and managerial power as competing hypotheses, it is more productive to acknowledge that outside-dominated boards mitigate agency problems between managers and shareholders but create agency problems between shareholders and directors. Rigidly adopting either extreme hypothesis—that director incentives are fully aligned with shareholder preferences or with those of incumbent CEOs—will inevitably result in less interesting and less realistic conclusions.

More importantly, viewing executive compensation as a “horse race” between efficient contracting and managerial power ignores other forces that may be even more important in explaining trends in pay. A central theme of this study is that government intervention into executive compensation—largely ignored by researchers—has been both a response to and a major driver of time trends in CEO pay. The reason political influence on CEO pay adds an important new dimension to the agency problem is because the interests of the government differ significantly from those of shareholders, directors, and executives. In particular, Congressional (and, more generally, populist) outrage over executive pay is almost always triggered by perceived excesses in the level of compensation without regard to incentives and company performance, and the regulatory responses have also fixated on pay levels (albeit with little effect). In contrast, while shareholders have a legitimate concern over pay levels, their primary concern is whether executives have incentives to take actions that increase firm value, while avoiding value-destroying actions. Self-interested CEOs naturally prefer higher pay to lower pay. Directors, who are elected by shareholders but often selected by CEOs, appear to prefer better-aligned incentives but are not particularly interested in restraining pay levels.

5.1 Agency Problems: Solutions and Sources

The early 1900s witnessed the emergence of large publicly traded corporations with complex management structures that competed with and often displaced owner-managed and family-founded enterprises. Accompanying the rise in the “American Corporation” was the emergence of “professional executives”—non-owners hired to manage the firm’s assets on behalf of passive and dispersed owner-shareholders (Wells, 2010). As noted by Smith (1776) in the context of 18th-century British “joint-stock” companies:

“Being managers rather of other people’s money than of their own, it cannot well be expected, that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private copartnery frequently watch over their own…Negligence and profusion, therefore, must always prevail, more or less, in the management of the affairs of such a company.”

The conflicts identified by Smith (1776) arising between the owners of large publicly traded corporations and their hired executives is the quintessential “agency problem” explored by Berle and Means (1932) and Jensen and Meckling (1976). There are at least three versions of this agency problem:

• The Agency Cost of Equity, reflecting the fact that executives who own less than 100% of the shares of an all-equity firm will not make the same decisions (or “watch over it with the same anxious vigilance”) they would if they owned 100% of the shares. Executives (usually assumed to be risk averse) want to be paid more and to take actions that increase their own utility, while shareholders (usually assumed to be risk neutral, or close to it) are primarily concerned with providing executives with incentives to take actions that increase the value of their shares.

• A variant of the Agency Cost of Equity is the “Agency Cost of Free Cash Flow” proposed by Jensen (1986a), reflecting the conflict of interest between executives and financial claimants on the disposition of cash flows in excess of those required to fund all positive net-present-value projects. While value is maximized by returning free cash flow to shareholders in the form of dividends or repurchases, empire-building executives prefer to retain and reinvest free cash flow unproductively in projects that destroy shareholder value. Debt financing mitigates free cash flow problems by pre-committing executives to pay out rather than retain future cash flows.

• The Agency Cost of Debt, reflecting the potential conflict of interest that exists between a company’s shareholders and its debtholders: shareholders in a leveraged firm prefer riskier investments than those that would maximize firm value, while debtholders prefer safer investments than those that would maximize firm value.156 In addition, dividends and other payouts to shareholders may harm debtholders by jeopardizing the company’s ability to service its debt. While the Agency Cost of Debt is clearly valid conceptually, there is little empirical evidence that leverage indeed leads to excessive risk taking, for several reasons. First, precisely because these conflicts are well understood, the potential problem is mitigated through debt covenants and constraints on how the proceeds from debt financing can be used. Moreover, since the problem is “priced” into the terms of the debt (with debtholders charging higher interest råtes in situations where executives have incentives to take higher risks), firms anticipating repeat trips to the bond market are directly punished for their risky behavior. The potential for conflicts are exacerbated, however, when the debtholders (or other fixed claimants, such as depositors) are protected against losses by the government. Such government guarantees can be explicit (such as FDIC insurance on deposits) or implicit (such as “Too Big To Fail” (TBTF) guarantees)). In these situations, the debtholders (or depositors) have little incentive to monitor management or enforce debt covenants, since the government is expected to cover losses.

While the labels on the various agency problems may be useful, they are all examples of the underlying agency conflict that arises when decision makers do not bear 100% of the wealth consequences of their decisions. As emphasized by Jensen (1993) there are four forces that mitigate agency problems between executives and the owners of large publicly traded corporations: (1) boards of directors; (2) capital markets; (3) the legal/political/regulatory system; and (4) product markets. However, while each of these forces can (and have) played a productive role in reducing agency conflicts, they also can (and have) created new problems, as follows.

5.1.1 Boards of Directors

The first line of defense against agency problems is the board of directors, elected by shareholders and responsible for monitoring, hiring, firing, and setting the compensation of the CEO and top-management team. For most of the prior century, boards were dominated by current executives and other corporate insiders. However, beginning with the shareholder movement in the 1980s (Section 3.6.2 above), firms have faced pressures for increased outsider representation on boards. By the end of the 1990s, the fraction of outside directors serving on the average board had increased to 80%, and the CEO was the sole insider in nearly half of all firms (Horstmeyer, 2011).

Conceptually, outside directors reduce agency problems by threatening errant executives with termination and by implementing incentive contracts that tie pay to value creation. The contracts that evolve from this setting will typically tie CEO pay to the creation of shareholder value, thus providing the theoretical justification for stock options, restricted stock, and other forms of equity-based compensation. Under the efficient contracting hypothesis, the contracts will be those that maximize shareholder value, while paying the CEO enough “expected” compensation or utility to get him to take the job, and recognizing that CEOs will respond predictably to the incentives provided by the contract.157

However, outside directors—who often own only a trivial fraction of their firm’s common stock—are in no sense perfect agents for the shareholders who elected them. Board members are “reluctant to terminate or financially punish poor-performing CEOs because [board members] personally bear a disproportionately large share of the non-pecuniary costs [of such terminations], but receive essentially none of the pecuniary benefits” (Baker, Jensen, and Murphy, 1988, p. 614). Similarly, board members are willing to over-compensate adequately performing CEOs, since they are paying with shareholder money and not their own. As documented by Fracassi and Tate (2012), even “outside” board members often share important social ties with incumbent CEOs, especially in cases with powerful CEOs who presumably influence the director-nomination process. This agency problem between shareholders and their elected representatives forms the basis of the “managerial power hypothesis”, in which powerful CEOs are able to influence both the level and composition of their own compensation packages. However, as discussed in Section 5.2.1 below, the agency problem is perhaps even more apparent in situations not involving powerful incumbents, such as directors overpaying CEOs hired from the outside.

5.1.2 Capital Markets

As discussed in Section 3.6.1, the executive compensation practices of the 1970s provided few incentives for executives to pursue value-increasing reductions in excess capacity and disgorgements of excess cash. However, pressures to improve performance, disgorge cash, and create wealth were ultimately introduced by the capital markets. The takeovers in the 1980s—often financed with newly available high-yield debt—provided credible competition for poorly performing incumbent managers. Wealth was created by both the post-merger activities of the acquiring firms (such as firing incompetent incumbent managers) and by responses to the takeover threat (such as excess spending cash to repurchase shares). Debt created value by providing commitments that the firm would pay its cash flows to debtholders, reducing the amounts available for executives to waste.

Capital markets—in particular, shareholder activists and large-block institutional stockholders—have mitigated agency problems by pressuring companies to strengthen links between CEO wealth and company stock-price performance. Fernandes et al. (2013), for example, show that the fraction of CEO pay delivered in the form of stock or options increases with institutional ownership. Hartzell and Starks (2003) show that CEO pay-performance sensitivities increase with the concentration of institutional ownership. In an international study, Aggarwal et al. (2011) find that the performance-related CEO turnover also increases with institutional ownership.

Capital markets have also, however, contributed to agency problems by providing executives with incentives to take actions to meet or beat analyst and market earnings expectations. As discussed in Section 2.4 and shown in Figure 12, executives have incentives to beat analysts forecasts by a small amount but not by too much because the abnormal stock-price response from beating the forecast by a lot is not much higher than the response for beating it by a little. Moreover, if an executive is going to miss the forecast, the executive may as well miss it by a lot since the negative abnormal stock-price response for a large miss is not much higher than for a small miss.

More generally, as argued by Jensen and Murphy (2012) and Martin (2011), capital-market pressures teach executives to focus on the “expectations market” (in which investors bet on expectations of future performance) rather than the “real market” (in which goods and services are produced and sold, and value is created or destroyed). Focusing on the expectation market is problematic because executives inherently have access to information about future prospects that are not publicly known and incorporated into stock prices. Executives with such a focus will be tempted to take actions that increase short-run stock prices at the expense of long-run value.

Temptations to manipulate the expectations market will clearly be higher for executives holding large quantities of stock and options that can be sold or exercised before markets adjust to the “real” information. As discussed in Section 2.4, there is substantial evidence that executive option and equity holdings are indeed higher in companies that restate their earnings or are accused of accounting fraud.158 There is less evidence, however, that executives actually exercise and sell large fractions of their exercisable options or sell large fractions of their unrestricted stock holdings prior to restatements or indictments. The ominous hypothesis is that executives focused on the expectations market are not following a “pump and dump” strategy (which can be controlled by imposing longer holding requirements for shares), but rather that they are legitimately confused about the difference between increases in the short-run stock price and true value creation.

5.1.3 The Political, Legal, and Regulatory System

Agency costs are mitigated by laws prohibiting embezzlement, corporate theft, and fraudulent conveyance, as well as securities rules, regulations, and listing requirements designed to protect shareholders and other financial claimants. For example, the Securities Act of 1933—which regulated new securities issues—sought to protect shareholders by mandating full disclosure of all information that a “reasonable shareholder” would require in order to make up his or her mind about the potential investment. The Securities Act of 1934—which regulated secondary trading of securities—introduced in Section 16(b) the “short swing” profit rule (discussed above in Section 3.5.4) requiring executives to return any profits realized from buying and selling (or selling and buying) shares of their company’s stock within any period of less than six months. More sweeping (at least in its interpretation) was the anti-fraud provision Section 10(b) (and the corresponding SEC 10b-5 rule), which restricts insider trading, earnings manipulation, and price fixing. More recently, Regulation FD (August 2000) requires publicly traded companies to disclose material information to all investors at the same time (rather than favoring certain investors). While there are substantive arguments for allowing trading on material nonpublic information (since new information is more quickly introduced into the market), insider-trading rules are generally believed to benefit shareholders by reducing self-dealing by unscrupulous executives.

In addition to the general Securities Acts, the government has directly regulated the composition of the board of directors. Since 1994, companies have been required to have compensation committees consisting solely of independent directors in order for any pay to be exempt from the $1 million deductibility cap. In 1999, full independence of the auditing committee was required for all NYSE-listed firms; this requirement was extended to all firms in the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act. In 2003, NYSE and NASDAQ listing requirements tightened the definition of independence and mandated that boards of listed firms have a majority of outside directors; the NYSE further required full independence for the compensation and nominating committees.

Critics hoping that independence requirements would reduce levels of executive pay have been disappointed. Both the level of pay and the use of equity-based compensation increase with the fraction of outsiders on the board; Fernandes et al. (2013) show that pay levels increase with board independence even after controlling for the risk associated with higher incentives. The evidence is therefore consistent with the hypothesis that directors—paying with shareholder money and not their own—prefer better-aligned incentives but are not particularly interested in restraining pay levels. The evidence is also consistent with directors not fully understanding (or believing) the opportunity cost of equity-based compensation (see Section 5.2.3 below).

Moreover, evidence that board independence “improves” pay is elusive. Bizjak and Anderson (2003) analyze the level and structure of compensation for CEOs who sit on their companies’ compensation committees (a relatively common occurrence before the early 1990s). Most critics of CEO pay (including Bebchuk–Fried and many shareholder activists) are horrified by the idea that the CEO could be a member of his own compensation committee, and would predict that such CEOs would inflate their own pay with few constraints.159 And yet, Bizjak and Anderson (2003) find that the CEOs sitting on their own compensation committees earn substantially less (and not more) than other CEOs, have significant shareholdings and are typically company founders or their family members. These CEOs sit on their compensation committees not to inflate their own salaries, but rather to influence the level and structure of pay for their subordinates. Prohibiting such CEOs from sitting on (or chairing) their compensation committees harms shareholders, and illustrates a cost of the “one-size-fits-all” nature of corporate governance regulation.

In addition to general securities laws and independence requirements, this study has chronicled the history of government intervention into executive compensation. Over the past 80 years, Congress has imposed tax policies, accounting rules, disclosure requirements, direct legislation, and other rules designed explicitly to address perceived abuses in executive compensation. With few exceptions, the regulations have been either ineffective or counterproductive, typically increasing (rather than reducing) agency problems and pay levels, and leading to a host of unintended consequences. For example, the 1984 laws introduced to reduce golden parachute payments led to a proliferation of change-in-control arrangements, employment contracts, and tax gross-ups. Similarly, a variety of rules implemented in the early 1990s are largely responsible for fueling the subsequent option explosion, and the enhanced disclosure of perquisites in the 1970s is generally credited with fueling an escalation in the breadth of benefits offered to executives.

The emerging conclusion is that the myriad attempts to regulate CEO pay have been mostly unblemished by success. Part of the problem is that regulation—even when well intended—inherently focuses on relatively narrow aspects of compensation allowing plenty of scope for costly circumvention. An apt analogy is the Dutch boy using his fingers to plug holes in a dike, only to see new leaks emerge. The only certainty with pay regulation is that new leaks will emerge in unsuspected places, and that the consequences will be both unintended and costly.

Another part of the problem—as suggested above in the context of CEOs sitting on their firm’s compensation committees—is that government regulation inevitably imposes a “one-size-fits-all” solution to a perceived problem. For example, as I emphasize in Murphy (2012), claims (unfounded or not) that the banking bonus culture created incentives to take excessive risks were relevant at most for a relatively small number of large publicly traded Wall Street security brokers and dealers (along with some large commercial banks with significant investment banking operations). And yet, the Dodd–Frank provisions designed to reduce such incentives in the future were imposed on all public and private financial institutions, including broker-dealers, commercial banks, investment banks, credit unions, savings associations, domestic branches of foreign banks, and investment advisors.

A larger part of the problem is that the regulation is often mis-intended. The regulations are inherently political and driven by political agendas, and politicians seldom embrace “creating shareholder value” as their governing objective. While the pay controversies fueling calls for regulation have touched on legitimate issues concerning executive compensation, the most vocal critics of CEO pay (such as members of labor unions, disgruntled workers and politicians) have been uninvited guests to the table who have had no real stake in the companies being managed and no real interest in creating wealth for company shareholders. Indeed, a substantial force motivating such uninvited critics is one of the least attractive aspects of human beings: jealousy and envy. Although these aspects are seldom part of the explicit discussion and debate surrounding pay, they are important and impact how and why governments intervene into pay decisions.

5.1.4 Product Markets

While competition in the product market can theoretically either reduce or increase agency problems (see Hart, 1983; Scharfstein, 1988 respectively), companies that cannot compete in the product market cannot survive. The product market, therefore, provides inevitable discipline for value-destroying managers, but only after most of the value has been destroyed. Moreover, relying on product markets to discipline managers encourages managers to view “survival” rather than value-creation as their governing objective.

5.2 “Competing” Hypotheses to Explain the Increase in CEO Pay

The unparalleled rise in CEO pay from the mid-1980s through 2001—propelled primarily by increases in the grant-date value of option awards—generated a great deal of academic, popular, and political attention. As noted, most papers in the literature have offered either the “managerial power” or “efficient contracting” explanations for the increase; see Frydman and Jenter (2010) for a useful and thoughtful review. A third set of explanations—most closely associated with Murphy (2002)—maintains that options exploded in the 1990s because decisions over options were made based on the “perceived cost” of options rather than on their economic cost. This section summarizes and critiques all three approaches, focusing on salient features of CEO pay that can, and cannot be explained under the approach. In addition, I explore the government’s role in pursuing social policy that favored stock options for both top-level executives and lower-level employees.

Before assessing how well the various theories explain the recent trends in CEO pay, it is useful to summarize what those trends are (that is, what the theories need to explain):

• Median expected pay for CEOs in the S&P 500 increased an average of 4.3% annually (after inflation) from 1983-1991, and by an average of 15.7% annually between 1991 and 2001.

• Most of the increase in pay between 1991 and 2001 reflects increases in the value of stock options granted.

• The “stock option explosion” was not limited to CEOs: 95% of the option grants went to lower-level executives and employees, and the trends in CEO options mirrored trends for options to lower levels.

• Median CEO pay has largely leveled-off since 2001. Over the same time period, firms have reduced their reliance on stock options and greatly increased their use of restricted stock and performance shares.

Therefore, any compelling theory of trends in CEO compensation must not only explain the increase in pay levels but must also address explicitly its most prominent feature: the escalation in stock options from the mid-1980s through 2001. Better still, the theory should be consistent with the explosion in broad-based option programs, the leveling of pay after 2001 and the emerging dominance of restricted stock.

5.2.1 Managerial Power

The “managerial power” approach begins with the self-interested executives envisioned by Berle and Means (1932) and Jensen and Meckling (1976) and adds a new element: the ability of these executives to influence both the level and composition of their own compensation packages, often (if not invariably) at the expense of shareholders. One of the early contributors to this view is David Yermack, who has argued that CEOs extract rents from shareholders by timing their option grants to occur just before the release of good news (Yermack, 1997), by insider trading through their family charitable foundations (Yermack, 2009), through lucrative severance and change in control provisions (Hartzell, Ofek, and Yermack, 2004; Yermack, 2006b; Dahiya and Yermack, 2008), and by consuming excessive perquisites (Yermack, 2006a).

The researchers most closely associated with the managerial power approach are Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried, who have argued in a series of papers that both the level and composition of pay are determined not by competitive market forces but rather by captive board members catering to rent-seeking entrenched CEOs.160 In addition, the authors argue that the CEO’s ability to extract rent is limited by outside scrutiny and criticism (the “outrage constraint”), and CEOs respond by extracting rents through difficult-to-observe or assess forms of compensation rather than through increased base salaries. They use their model to explain several common features of executive compensation plans, including the use (and misuse) of compensation consultants, the prevalence of stealth compensation (pensions, deferred pay, perquisites, and loans), gratuitous severance payments, and stock options that are uniformly granted at the money and not indexed for the market or industry.

Can managerial power explain the trends in CEO pay? There is no doubt that executives (like the rest of us) are self-interested and would prefer higher compensation to lower compensation. There is also little doubt that—while CEOs are never explicitly involved in setting their own pay (even those sitting on their own compensation committees)—CEOs have subtle ways of influencing the compensation committee and the pay-setting process.161 However, as emphasized by Holmstrom and Kaplan (2003) and Frydman and Jenter (2010), there is no evidence that boards have become weaker or more captive over time. Indeed, every measure of board independence has improved since the mid-1980s. As discussed in Sections 5.1.1, the fraction of outside directors serving on the average board had increased to 80% by the end of the 1990s, and the CEO was the sole insider in nearly half of all firms. Since IRS Section 162(m) in 1993 (which required independence as a prerequisite for deductibility), most compensation committees have been fully independent. The 2003 NYSE listing requirements and 2010 Dodd–Frank Section 952 are appropriately characterized as tightening the definition from “independent” to “really independent” to “really, really independent”, reflecting a mistaken belief that true independence can be measured by an objective standard applicable across all publicly traded companies without regard to the individual director. The increase in board independence during the 1990s should reduce managerial influence over pay, suggesting that the trends in CEO pay over the period were not driven by managerial power. In addition, the secular increase in disciplinarily firings of poorly performing CEOs (Kaplan and Minton, 2011; Huson, Parrino, and Starks, 2001) offers no evidence that boards are becoming systematically more passive over time.

Moreover, it is worth noting that many of the most generous and widely criticized option and severance payouts over the past two decades have been the direct result of formal employment agreements negotiated with external candidates, and not deals reached with powerful incumbents. Indeed, Murphy and Zábojník (2008) attribute the increase in executive pay to the increased prevalence of hiring CEOs from outside the firm. During the 1970s, under 15% of newly appointed CEOs were hired externally. By, the late 1990s, nearly a third of all CEO appointments came from outside of the firm, suggesting increasing competition in the managerial labor market. While the Murphy–Zábojník results (discussed in the next section) are often cited as evidence for the “efficient-contracting” approach, they are also consistent with directors systematically overpaying (and over-protecting) CEOs brought in from outside the firm.

In fact, compensation committees almost invariably pay “too much” for newly appointed CEOs, especially for those hired from outside the firm. Corporate directors seeking new CEOs from outside typically hire a professional search firm to identify qualified candidates for the position (Khurana, 2002a, 2002b). The pool of qualified candidates is narrowed through extensive research, background and reference checks, and interviews until a single individual is selected for the position. Negotiations over pay typically begin only after the favored candidate is identified and told that he or she is to be the new CEO. Indeed, many times negotiations are still on-going when the appointment is announced publicly. At this point the board is effectively locked in to the particular candidate CEO, which dramatically shifts the bargaining power to the seller (the candidate) rather than the buyer (the firm). This procedure is a reasonable way to identify top candidates when “price” is not an issue, but is clearly a recipe for systematically paying too much for managerial talent.

The tendency to pay too much and to pay it in the wrong way is exacerbated by potential CEOs who hire skilled contracting agents to negotiate on their behalf. In contrast, compensation committees rarely retain their own expert negotiators. The outcome is what one would expect in a game where there is such a clear mismatch: no matter how well intentioned, the typical compensation committee is no match against a professional negotiator, and overly generous pay packages become ubiquitous. But often the problem is worse: the incoming CEO (and his professional agent) negotiate not with the compensation committee but rather with the company’s general counsel or head of human resources, knowing they will report to the CEO when the contracting is complete.

Overpaying newly hired CEOs is an agency problem caused by directors paying the new hires with shareholder money rather than their own. It is not, however, a “managerial power” problem, since the board is not captive and these are arms’ length negotiations with a non-incumbent CEO candidate. The distinction is important because the policy prescriptions are different: the solution to overpaying new hires is to strengthen the negotiation process, while the solution to managerial power is to weaken the incumbent CEO’s influence. More importantly, the “problem” of overpaying (and over-protecting) new hires may be small compared to the costs of selecting the wrong CEO.

In any case, hiring managerial talent from either inside or outside the firm is expensive, and the price of talent increased significantly during the 1990s and early 2000s. Kaplan and Rauh (2010) and Kaplan (2008), for example, present evidence that the increased pay for top executives is comparable to pay trends for top lawyers, investment bankers, hedge-fund managers, venture capitalists, private-equity managers, and athletes. The rise in incomes for top talent in these disparate sectors—most with active and mobile labor markets—cannot plausibly be explained by managerial power. It seems unproductive to attribute gains in these other sectors to competitive market forces while inventing a different explanation for the rise in CEO pay. Indeed, the secular increase in external CEO appointments documented by Murphy and Zábojník (2008) suggests that the managerial labor market is becoming more rather than less competitive.

Can managerial power explain the growth in the use of stock options?Bebchuk, Fried, and Walker (2002) suggest that firms can “camouflage” excessive pay by substituting stock options for cash compensation, under the theory that such grants are difficult to value and are easy to hide in annual disclosures. Under disclosure rules effective before 1992, information on option grants was indeed difficult to obtain.162 However, the centerpiece of the sweeping new disclosure rules introduced in October 1992 focused on option grants, and two new tables were added to the proxy statements to describe the details of both the grant and the number and value of options held at the end of the year. Bebchuk, Fried, and Walker (2002) would predict that options grants would fall as the amount of information increased. However, option grants escalated (rather than fell) following the new rules.

Bebchuk and Grinstein (2005) attempt to provide a managerial power explanation for the 1990s increase in stock options as follows. First, they argue that the stock market boom weakened the outrage constraint, giving executives more latitude to increase their own pay. Second, they argue that increasing compensation in the form of options caused less outrage than increasing base salaries, not because of “camouflage” but because options offered the possibility of improved incentives. When the market declined in 2000–2002, the outrage constraint strengthened as investors became less forgiving of perceived managerial over-reaching, stemming the escalation in both pay and the use of stock options. Bebchuk and Grinstein (2005) use this framework to explain the correlation between CEO pay and general stock-price movements, as illustrated in Figure 18 in Section 3.7.5. Their framework would therefore also predict an increase in pay and options during the 2003–2007 bull market, and yet pay increases were modest and options were declining over this period. They could, of course, provide arguments for the existence of an “outrage constraint” for this period that would explain why pay levels moderated and options were replaced by restricted stock. This points to a basic problem with the Bebchuk and Grinstein (2005) explanation (and the managerial-power hypothesis more generally): there is no principled way to refute any trend in pay given the authors’ flexible (and unmeasurable) definition of both the “outrage constraint” and its importance.

5.2.2 Efficient Contracting

The “efficient contracting” camp maintains that the observed level and composition of compensation reflects a competitive equilibrium in the market for managerial talent, and that incentives are structured to optimize firm value. The survey article by Edmans and Gabaix (2009) considers optimal-contracting explanations for the pay practices criticized under the managerial power camp, and the survey article by Frydman and Jenter (2010) discuss how these theories can predict increases in CEO pay over time.

Unlike the “managerial power” camp, the “efficient contracting” camp is not neatly characterized by a well-defined set of authors or articles. The modern executive compensation literature paralleled the emerging agency theory literature, and the majority of CEO pay papers written since the 1980s have been explicitly or implicitly based on agency or optimal-contracting theories. Indeed, the managerial power approach largely evolved as researchers—perhaps beginning with Jensen and Murphy (1990b) and Yermack (1995)—uncovered anomalies seemingly inconsistent with optimal contracts.

Can efficient contracting explain the trends in CEO pay? Beyond optimal incentive contracts, the efficient contracting approach includes market equilibrium models of managerial productivity, matching, and sorting that predict secular increases in CEO pay. For example, Murphy and Zábojník (2008) and Frydman (2007) offer general equilibrium models attributing the increase in executive pay to the increased prevalence of hiring CEOs from outside the firm. In particular, both papers attribute the trend toward outside hiring as reflecting gradual changes in the nature of the CEO job, modeled as a shift in the relative importance of general “managerial capital” (human capital specific to CEO positions) over firm-specific capital (reflecting skills, knowledge, contacts, and experience valuable only within the organization). The shift in the relative importance of general vs. firm-specific managerial capital leads to fewer promotions, more external hires, and an increase in equilibrium average wages for CEOs relative to the wages of lower-level workers. Ultimately, while it is plausible that the increased prevalence of outside hiring will increase average wages (if nothing else, employers must always pay a premium when hiring from outside compared to promoting from within), it is less plausible that the doubling of outside hiring from the 1970s to the 2000s could lead to such a huge increase in real CEO pay over this time period.

Alternatively, Gabaix and Landier (2008) build an equilibrium model in which the marginal product of managerial ability increases with firm size (so that it is optimal to assign the most talented managers to the largest firms). As shown by Rosen (1981) and Rosen (1982), such assortative matching produces equilibrium wages that are convex in ability, such that small increases in ability can lead to large increases in wages (since the CEO is assigned to a larger firm). Gabaix and Landier (2008)’s key insight is that the wage of a CEO will depend not only on firm size, but also on the size distribution of all firms in the relevant market: as the average firm becomes larger, managerial marginal products increase and competition for scarce managerial talent will bid up compensation. In particular, they show that a shift in the size distribution of firms will lead to a proportional shift in compensation, and conclude that “the six-fold increase in CEO pay between 1980 and 2003 can be fully attributed to the six-fold increase in market capitalization of large US companies”.

Gabaix and Landier (2008)’s results are consistent with the near-perfect correlation between CEO pay and general stock-price movements observed from 1980 to 2002 (see Figure 18 in Section 3.7.5). However (and similar to the critique of Bebchuk and Grinstein (2005) above), their results are not consistent with time trends in CEO pay and the stock market since 2002. In addition, while their insights on the size distribution are potentially important, their focus on market capitalization as the size measure is problematic since it conflates size, stock-price performance, and the vagaries of the market. Few would argue, for example, that Apple was really the largest firm in the world economy in 2012 (and yet their market value in early 2012 eclipsed that of Exxon-Mobil, PetroChina, and Royal Dutch Shell). Similarly, Volkswagen was not the second-largest firm on the planet for a couple of days in late October 2008 after its stock price increased by 350% over a two-day period (before tumbling by 60% over the following week).163 While average CEO pay may have moved roughly proportionately with average market capitalization between 1980 to 2003, it far outpaced the growth in more traditional measures of size. For example, average revenues for the 500 largest US firms ranked by revenue grew only by 50% after inflation from 1980 to 2003, while average employment for the 500 largest US employers grew only by 19%.164