Chapter 6

Law and Finance After a Decade of Research* **

Abstract

Keywords

Corporate governance; Law and finance; Financial development; Financial regulation; Investor protection; Corporate and securities laws; Bankruptcy and reorganization

JEL classification

G150; G320; G380; G330; G340; G350; K200; K220; O160; P500

1 Introduction

Several years ago, the three of us together with Vishny published a pair of articles dealing with legal protection of investors and its consequences (La Porta et al. 1997, 1998 or LLSV). These articles generated a fair amount of follow-up research, and some controversy. This paper is our attempt to summarize the main findings of this literature, particularly with respect to financial markets, and to interpret them in a unified way.

LLSV started from a proposition, standard in corporate law (e.g. Clark, 1986) and emphasized by Shleifer and Vishny (1997), that legal protection of outside investors limits the extent of expropriation of such investors by corporate insiders, and thereby promotes financial development. From there, LLSV made two contributions. First, they showed that legal rules governing investor protection can be measured and coded for many countries using national commercial (primarily corporate and bankruptcy) laws. LLSV coded such rules for both the protection of outside shareholders, and the protection of outside senior creditors, for 49 countries. The coding showed that some countries offer much stronger legal protection of outside investors’ interests than others.

Second, LLSV documented empirically that legal rules protecting investors vary systematically among legal traditions or origins, with the laws of common law countries (originating in English law) being more protective of outside investors than the laws of civil law (originating in Roman law) and particularly French civil law countries. LLSV further argued that legal traditions were typically introduced into various countries through conquest and colonization, and as such were largely exogenous. LLSV then used legal origins of commercial laws as an instrument for legal rules in a two stage procedure, where the second stage explained financial development. The purpose was to overcome the reverse causality argument that financial development causes legal development.

Subsequent research showed that the influence of legal origins on laws and regulations is not restricted to finance. In several studies conducted jointly with Simeon Djankov and others, we found that such outcomes as government ownership of banks (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer, 2002a), the burden of entry regulations (Djankov et al. 2002), regulation of labor markets (Botero et al. 2004), incidence of military conscription (Mulligan and Shleifer, 2005a, 2005b), and government ownership of the media (Djankov et al. 2003) vary across legal families. In all these spheres, civil law is associated with a heavier hand of government ownership and regulation than common law. Many of these indicators of government ownership and regulation are associated with adverse impacts on markets, such as greater corruption, larger unofficial economy, and higher unemployment.

In still other studies, we have found that common law is associated with lower formalism of judicial procedures (Djankov et al. 2003) and greater judicial independence (La Porta et al. 2004) than civil law. These indicators are in turn associated with better contract enforcement and greater security of property rights.

The LLSV studies have generated a considerable amount of follow-up research, particularly in the area of investor protection, as well as some criticism. Although it is not possible for us to summarize all of this research, we will seek to describe some of the main themes, particularly in the area of law and finance. We do not, in this paper, attempt to summarize the more recent body of work on regulation and regulatory reform.

Assuming that this evidence is correct, it raises an enormous challenge of interpretation. What is the meaning of legal origin? Why is its influence so pervasive? How can the superior performance of common law in many areas be reconciled with the high costs of litigation, and well-known judicial arbitrariness, in common law countries?

In this paper, we adopt a broad conception of legal origin as a style of social control of economic life (and maybe of other aspects of life as well). In strong form (later to be supplemented by a variety of caveats), we argue that common law stands for the strategy of social control that seeks to support private market outcomes, whereas civil law seeks to replace such outcomes with state-desired allocations. In words of one legal scholar, civil law is “policy implementing”, while common law is “dispute resolving” (Damaška, 1986). In the words of another, French civil law embraces “socially-conditioned private contracting”, in contrast to common law’s support for “unconditioned private contracting” (Pistor, 2006). We develop an interpretation of the evidence, which we call the Legal Origins Theory, based on these fundamental differences.

Legal Origin Theory traces the different strategies of common and civil law to different ideas about law and its purpose that England and France developed centuries ago. These broad ideas and strategies were incorporated into specific legal rules, but also into the organization of the legal system, as well as the human capital and beliefs of its participants. When common and civil law were transplanted into much of the world through conquest and colonization, not only the rules, but also human capital and legal ideologies, were transplanted as well. Despite much local legal evolution, the fundamental strategies and assumptions of each legal system survived, and have continued to exert substantial influence on economic outcomes. As the leading comparative legal scholars Zweigert and Kötz (1998) emphasize, “the style of a legal system may be marked by an ideology, that is, a religious or political conception of how economic or social life should be organized” (p. 72). In this paper, we show how these styles of different legal systems have developed, survived over the years, and continued to have substantial economic impact. As we see it, legal origins are central to understanding the varieties of capitalism.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we describe the principal legal traditions. In Section 3, we document the strong and pervasive effects of legal origins on diverse areas of law and regulation, which in turn influence a variety of economic outcomes. Our emphasis in this section, however, is on law and finance, and we seek to summarize some of the research done in the last dozen years. We address such topics as tunneling by insiders, concentrated corporate ownership, and the many consequences of differences in shareholders’ and creditors’ rights for financial outcomes. In Section 4, we outline the Legal Origins Theory, and interpret the findings from that perspective. In Sections 5–7, we deal with three lines of criticism of our research, all organized around the idea that legal origin is a proxy for something else. The three alternatives we consider are culture, politics, and history. Our strong conclusion is that, while all these factors influence laws, regulations, and economic outcomes, it is almost certainly false that legal origin is merely a proxy for any of them. Section 8 concludes the paper.

2 Background on Legal Origins

In their remarkable 300-page survey of human history, “The Human Web”, McNeill and William McNeill (2003) show how the transmission of information across space shapes human societies. Information is transmitted through trade, conquest, colonization, missionary work, migration, and so on. The bits of information transmitted through these channels include technology, language, religion, sports, but also law and legal systems. Some of these bits of information are transplanted voluntarily, as when people adopt technologies they need. This makes it difficult to study the consequences of adoption because we do not know whether to attribute these consequences to what is adopted, or to the conditions that invited the adoption. In other instances, the transplantation of information is involuntary, as in the cases of forced religious conversion, conquest, or colonization. These conditions, unfavorable as they are, make it easier to identify the consequences of specific information being transplanted.

Legal origins or traditions present a key example of such often-involuntary transmission of different bundles of information across human populations. Legal scholars believe that some national legal systems are sufficiently similar in some critical respects to others to permit classification of national legal systems into major families of law (David and Brierley, 1985; Glendon, Gordon, and Osakwe, 1992, 1994; Reynolds and Flores, 1989; Zweigert and Kötz, 1998). “The following factors seem to us to be those which are crucial for the style of a legal system or a legal family: (1) its historical background and development, (2) its predominant and characteristic mode of thought in legal matters, (3) especially distinctive institutions, (4) the kind of legal sources it acknowledges and the way it handles them, and (5) its ideology” (Zweigert and Kötz, 1998, p. 68).

All writers identify two main secular legal traditions: common law and civil law, and several sub-traditions—French, German, socialist, and Scandinavian—within civil law. Occasionally, countries adopt some laws from one legal tradition and other laws from another, and researchers need to keep track of such hybrids, but generally a particular tradition dominates in each country.

The key feature of legal traditions is that they have been transplanted, typically though not always through conquest or colonization, from relatively few mother countries to most of the rest of the world (Watson, 1974). Such transplantation covers specific laws and codes, the more general styles or ideologies of the legal system, human capital (sometimes through mother-country training), and legal outlook.

Of course, following the transplantation of some basic legal infrastructure, such as the legal codes, legal principles and ideologies, and elements of the organization of the judiciary, the national laws of various countries changed, evolved, and adapted to local circumstances. Cultural, religious, and economic conditions of every society came to be reflected in their national laws, so that the legal and regulatory systems of no two countries are literally identical. This adaptation and individualization, however, was incomplete. Enough of the basic transplanted elements have remained and persisted (David, 1985) to allow a classification into legal traditions. As a consequence, legal transplantation represents the kind of involuntary information transmission that the McNeills have emphasized, which enables us to study the consequences of legal origins.

Before discussing the legal traditions of market economies, we briefly comment on socialist law. The socialist legal tradition originates in the Soviet Union, and was spread by the Soviet armies first to the former Soviet republics and later to Eastern Europe.1 It was also imitated by some socialist states, such as Mongolia and China. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the countries of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe reverted to their pre-Russian-revolution or pre-World War II legal systems, which were French or German civil law. In our work based on data from the 1990s, we have often classified transition economies as having the socialist legal system. However, today, academics and officials from these countries object to such classification, so, in the present paper, we classify them according to the key influence on their new commercial laws. A couple of countries, such as Cuba, still maintain the socialist legal system, and await liberation and re-classification. These countries typically lack other data, so no socialist legal origin countries appear in the analysis in the present paper.

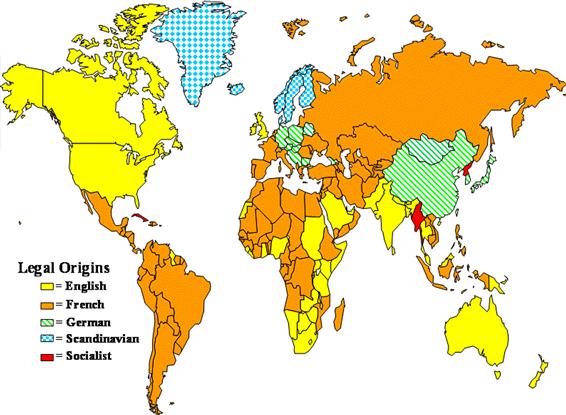

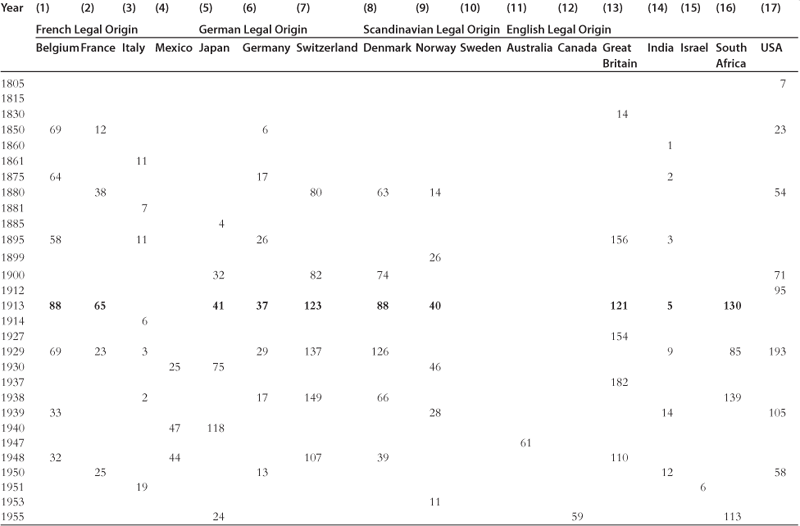

Figure 1 shows the distribution of legal origins of commercial laws throughout the world. The common-law legal tradition includes the law of England and its former colonies. The common law is formed by appellate judges who establish precedents by solving specific legal disputes. Dispute resolution tends to be adversarial rather than inquisitorial. Judicial independence from both the executive and legislature are central. “English common law developed because landed aristocrats and merchants wanted a system of law that would provide strong protections for property and contract rights, and limit the Crown’s ability to interfere in markets” (Mahoney, 2001, p. 504). Common law has spread to the British colonies, including the United States, Canada, Australia, India, South Africa, and many other countries. Of the maximal sample of 150 countries used in our studies, there are 42 common law countries.

Figure 1 The distribution of legal origin.

The civil law tradition is the oldest, the most influential, and the most widely distributed around the world, especially after so many transition economies returned to it. It originates in Roman law, uses statutes and comprehensive codes as a primary means of ordering legal material, and relies heavily on legal scholars to ascertain and formulate rules (Merryman, 1969). Dispute resolution tends to be inquisitorial rather than adversarial. Roman law was rediscovered in the Middle Ages in Italy, adopted by the Catholic Church for its purposes, and from there formed the basis of secular laws in many European countries.

Although the origins of civil law are ancient, the French civil law tradition is usually identified with the French Revolution and Napoleon’s codes, which were written in the early 19th century. In contrast to common law, “French civil law developed as it did because the revolutionary generation, and Napoleon after it, wished to use state power to alter property rights and attempted to insure that judges did not interfere. Thus, quite apart from the substance of legal rules, there is a sharp difference between the ideologies underlying common and civil law, with the latter notably more comfortable with the centralized and activist government” (Mahoney, 2001, p. 505).

Napoleon’s armies introduced his codes into Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy, and parts of Germany. In the colonial era, France extended her legal influence to the Near East and Northern and Sub-Saharan Africa, Indochina, Oceania, and French Caribbean Islands. Napoleonic influence was also significant in Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, and some Swiss cantons. When the Spanish and Portuguese empires in Latin America dissolved in the 19th century, it was mainly the French civil law that the lawmakers of the new nations looked to for inspiration. In the 19th century, the French civil code was also adopted, with many modifications, by the Russian Empire, and through Russia to the neighboring regions it influenced and occupied. These countries adopted the socialist law after the Russian Revolution, but typically reverted to the French civil law after the fall of the Berlin Wall. There are 84 French legal origin countries in the sample.

The German legal tradition also has its basis in Roman law, but the German Commercial Code was written in 1897 after Bismarck’s unification of Germany. It shares many procedural characteristics with the French system, but accommodates greater judicial law-making. The German legal tradition influenced Austria, the former Czechoslovakia, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, Yugoslavia, Japan, Korea, and a few countries of the former Soviet Union. Taiwan’s laws came from China, which relied heavily on German laws during modernization. There are 19 German legal origin countries in the sample.

The Scandinavian family is usually viewed as part of the civil law tradition, although its law is less derivative of Roman law than the French and German families (Zweigert and Kötz, 1998). Most writers describe the Scandinavian laws as distinct from others, and we have kept them as a separate family (with five members) in our research.

Before turning to the presentation of results, five points about this classification are in order. First, although the majority of legal transplantation is the product of conquest and colonization, there are important exceptions. Japan adopted the German legal system voluntarily. Latin American former Spanish and Portuguese colonies ended up with codifications heavily influenced by the French legal tradition after gaining independence. Beyond the fact that Napoleon had invaded the Iberian Peninsula, the reasons were partly the new military leaders’ admiration for Bonaparte, partly language, and partly Napoleonic influence on the Spanish and Portuguese codes. In this instance, the exogeneity assumption from the viewpoint of studying economic outcomes is still appropriate. The 19th century influence of the French civil law in Russia and Turkey was largely voluntary, as both countries sought to modernize. But the French and German civil law traditions in the rest of the countries in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Central Asia are the result of the conquests by the Russian, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and German empires. The return by these countries to their pre-Soviet legal traditions during the transition from socialism is voluntary, but shaped largely by history.

Second, because Scandinavian countries did not have any colonies, and Germany’s colonial influence was short lived and abruptly erased by World War I, there are relatively few countries in these two traditions. As a consequence, while we occasionally speak of the comparison between common and civil law, most of the discussion compares common law to the French civil law. This is largely because each tradition includes a large number of countries, but also because they represent the two most distinct approaches to law and regulation.

Third, although we often speak of common law and French civil law in terms of pure types, in reality there has been a great deal of mutual influence and in some areas convergence. There is a good deal of legislation in common law countries, and a good deal of judicial interpretation in civil law countries. But the fact that the actual laws of real countries are not pure types does not mean that there are no systematic differences.

Fourth, some have noted the growing importance of legislation in common law countries as proof that judicial law making no longer matters. This is incorrect, for a number of reasons. Statutes in common law countries often follow and reflect judicial rulings, so jurisprudence remains the basis of statutory law. Even when legislation in common law countries runs ahead of judicial law making, it often must coexist with, and therefore reflects, pre-existing common law rules. Indeed, statutes in common law countries are often highly imprecise, with an expectation that courts will spell out the rules as they begin to be applied. Finally, and most crucially, because legal origins shape fundamental approaches to social control of business, even legislation in common law countries expresses the common law way of doing things. For all these reasons, the universal growth of legislation in no way implies the irrelevance of legal origins.

Fifth, with the re-classification of transition economies from socialist into the French and German civil law families, one might worry that the differences among legal origins described below are driven by the transition economies. They are not. None of our substantive results change if we exclude the transition economies.

3 Some Evidence

3.1 Organizing the Evidence

Figure 2 organizes some of our own and related research on the economic consequences of legal origins. It shows the links from legal origins to particular legal rules, and then to economic outcomes. Figure 2 immediately suggests several problems for empirical work. First, in our framework, legal origins have influenced many spheres of law-making and regulation, which makes it dangerous to use them as instruments. Second, we have drawn a rather clean picture pointing from particular legal rules to outcomes. In reality, a variety of legal rules (e.g. those governing both investor protection and legal procedure) can influence the protection of outside investors and hence financial markets. This, again, makes empirical work less clean.

Figure 2 Legal origin, institutions, and outcomes.

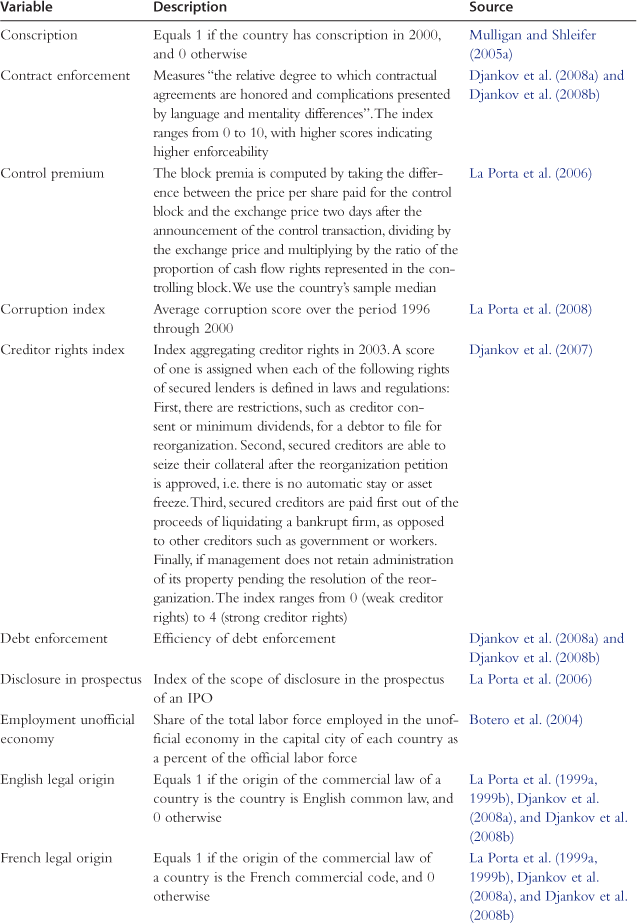

Before turning to the evidence, we make four comments about the data. First, all the data used in this paper, and a good deal more, are available at http://www.economics.harvard.edu/faculty/shleifer/data.html. We do not discuss the data in detail, but the descriptions are available in the original papers presenting the data.

Second, the basic evidence we present takes the form of cross-country studies. An important feature of these studies is that all countries receive the same weight. There is no special treatment of mother countries, of rich countries, etc. This design may obscure the differences, discussed below, within legal origins, such as the greater dynamism of law in mother countries than in former colonies.

Third, the sources of data on legal rules and institutions vary significantly across studies. Some rules, such as many indicators of investor protection and of various government regulations, come from national laws. Those tend to be “laws on the books”. Other indicators are mixtures of national laws and actual experiences, and tend to combine substantive and procedural rules. These variables are often constructed through collaborative efforts with law firms around the world, and yield summary indicators of legal rules and their enforcement. For example, the study of legal formalism (Djankov et al. 2003) reflects the lawyers’ characterization of procedural rules that would typically apply to a specific legal dispute; the study of the efficiency of debt enforcement (Djankov et al. 2008a; Djankov et al. 2008b) incorporates estimates of time, cost, and resolution of a standardized insolvency case. The procedure used in each study has its advantages and problems. An important fact, however, is the consistency of results across both data collection procedures and spheres of activity that we document below.

Fourth, over the years, various writers have criticized both the conceptual foundations of LLSV variables such as shareholder rights indices (Coffee, 1999) and the particular values we have assigned to these variables, in part because of conceptual ambiguity (Spamann, 2010). We have corrected our mistakes, but have also moved on to conceptually less ambiguous measures (Djankov et al. 2008b). These corrections have strengthened the original results. The findings we discuss below use the most recent data.

The available studies can be divided into three groups. First, several studies following LLSV (1997, 1998) examine the effects of legal origins on investor protection, and/or the effect of investor protection on financial outcomes. Second, several papers consider government regulation, and even ownership, of particular activities, and its relationship to legal origins. Third, several papers consider the relationship between legal origins, the characteristics of the judiciary and other government institutions, and the security of property rights and contract enforcement. We begin by discussing some of the evidence on law and finance, and then briefly consider the other evidence as well.

3.2 Investor Protection and Financial Markets

The conceptual framework for analyzing the effects of investor protection on financial markets is the contractual view of the firm (Aghion and Bolton, 1992; Grossman and Hart, 1986, 1988; Harris and Raviv, 1988; Hart, 1995; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Shleifer and Vishny, 1997). This view sees the protection of property rights of the financiers from expropriation by corporate insiders as essential to assuring the flow of capital to firms. In the law and finance context, this view holds that better legal protection of the rights of creditors and minority shareholders, through corporate law, bankruptcy law, securities law, or other body of law and regulation makes investors willing to provide capital to firms at a lower cost (e.g. Shleifer and Wolfenzon, 2002). To the extent that legal origin is a predictor of the quality of investor protection, it will, through this channel, influence financial outcomes.

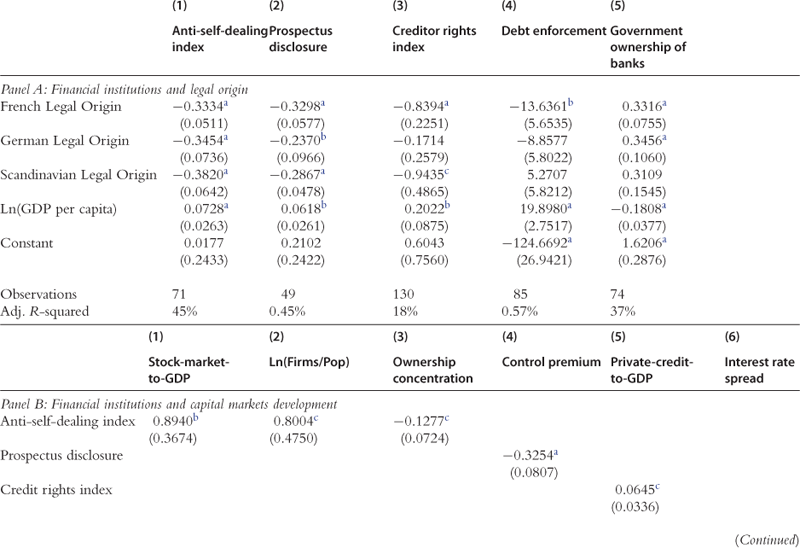

Table 1 shows a sampling of results on law and finance. The top panel presents the regressions of legal variables on legal origins, controlling only for per capita income. In the original papers, many more controls and robustness checks are included, but here we present the stripped down regressions. The bottom panel then presents some results of regressions of outcomes on legal rules. We could alternatively use legal origins as instruments for legal rules and regulations in a first stage regression, and then regress outcomes on predicted values of rules and regulations. The trouble with the instrumental variable approach is that legal origins influence outcomes through multiple channels, and hence the exclusion restriction on instruments is likely to be violated.

Table 1 Financial institutions and capital markets development

Note: Variable definitions and data sources are given in the Appendix.

aSignificant at the 1% level.

bSignificant at the 5% level.

cSignificant at the 10% level.

Table 1 is different from the original LLSV specifications in a number of ways. The LLSV measure of anti-director rights has been replaced by a regulation of disclosure in the prospectus (for new issues) from securities laws (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer, 2006) and the anti-self-dealing index capturing regulation of corporate insiders from corporate laws (Djankov et al. 2008b). Our key measure of stock market development is the ratio of aggregate stock market capitalization to gross domestic product (GDP; like LLSV), which reflects both the breadth of the market as reflected by the number of listed companies, and their valuation. We also consider the pace of public offering activity, the voting premium (see Dyck and Zingales, 2004), dividend payouts (La Porta et al. 2000), Tobin’s Q (La Porta et al. 2002b), and ownership dispersion (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer, 1999a). Predictions for each of these variables emerge from a standard agency model of corporate governance, in which investor protection shapes external finance (e.g. Shleifer and Wolfenzon, 2002), although as we note below, some ownership issues are complex.

Table 1 also looks at creditor rights. The LLSV (1997, 1998) measure from bankruptcy laws has been updated by Djankov, McLiesh, and Shleifer (2007). Djankov et al. (2008a) take a different approach to creditor protection by looking at the actual efficiency of debt enforcement, as measured by creditor recovery rates in a hypothetical case of an insolvent firm. The latter study addresses a common criticism that it is law enforcement, rather than rules on the books, that matters for investor protection by integrating legal rules and characteristics of enforcement in the efficiency measure. La Porta et al. (2002a) focus on state involvement in financial markets by looking at government ownership of banks. These studies typically consider the private credit to GDP ratio as an outcome measure, although Djankov et al. (2007) also examine several subjective assessments of the quality of private debt markets.

Turning to the results, higher income per capita is associated with better shareholder and creditor protection, more efficient debt collection, and lower government ownership of banks (Panel A). Civil law is generally associated with lower shareholder and creditor protection, less efficient debt enforcement, and higher government ownership of banks. The estimated coefficients imply that, compared to common law, French legal origin is associated with a reduction of 0.33 in the anti-self-dealing index (which ranges between 0 and 1), of 0.33 in the index of prospectus disclosure (which ranges between 0 and 1), of 0.84 in the creditor rights index (which ranges from 0 to 4), of 13.6 points in the efficiency of debt collection (out of 100), and a rise of 33 percentage points in government ownership of banks. The effect of legal origins on legal rules and financial institutions is statistically significant and economically large.

Higher income per capita is generally associated with more developed financial markets, as reflected in a higher stock-market-capitalization-to-GDP ratio, more firms per capita, less ownership concentration, a lower control premium, a higher private-credit-to-GDP ratio, and lower interest rate spreads. Investor protection is associated with more developed financial markets (Panel B). The estimated coefficients imply that a two-standard deviation increase in the anti-self-dealing index is associated with an increase in the stock-market-to-GDP ratio of 42 percentage points, an increase in listed firms per capita of 38 percentage points, and a reduction in ownership concentration of 6 percentage points. A two-standard deviation improvement in prospectus disclosure is associated with a reduction in the control premium of 0.15 (the mean premium is 0.11). The effect of legal rules on debt markets is also large. A two-standard deviation increase in creditor rights is associated with an increase of 15 percentage points in the private-credit-to-GDP ratio. A two-standard deviation increase in the efficiency of debt collection is associated with an increase of 27 percentage points in the private-credit-to-GDP ratio. A two-standard deviation increase in government ownership of banks is associated with a 16 percentage point rise in the spread between lending and borrowing rates (the median spread is 12).2

These results give only a flavor of the evidence on legal origins, investor protection, and financial markets. In the next few subsections, we discuss where the research in this area went.

3.3 Tunneling

One of the foundational assumptions of law in finance is that the central agency problem of the firm is the expropriation of outside investors by corporate insiders, whether controlling shareholders or managers (La Porta et al. 2002b; Shleifer and Vishny, 1997). The focus on investor expropriation distinguishes our approach from agency theories that focus on managerial effort (e.g. Holmstrom, 1979) or consumption of perquisites, which are a form of expropriation in kind (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Grossman and Hart (1988) and Harris and Raviv (1988) politely refer to the excess payoffs accruing to controlling shareholders as “private benefits of control”. In a study of a few legal cases in Europe related to investor expropriation, Johnson et al. (2000) use a term previously applied in the context of Czech privatization and refer to investor expropriation as tunneling. This term has stuck. In the last several years, researchers produced amazing evidence on tunneling.

Some of this evidence is indirect. Nenova (2003) and Dyck and Zingales (2004) focus on the premium at which controlling blocks of shares or voting (as opposed to non-voting) shares trade in different countries as an indirect measure of tunneling or private benefits of control. We use Dyck and Zingales (2004) data in Table 1. The idea of looking at takeover premia to infer tunneling has also been used by Franks and Mayer (2001) for German firms, Bae, Kang, and Kim, (2002) for Korean chaebol, and Cheung et al. (2006, 2009b) for related party acquisitions in Hong Kong, to give a few examples. Johnson, Boone, Breach, and Friedman (2000) and Lemmon and Lins (2003) also present indirect evidence of tunneling by comparing returns across firms and countries that are more and less likely to experience tunneling during the Asian financial crisis. This evidence adds up to a persuasive picture that private benefits of control are substantial in countries with poor investor protection, and in companies with dominant investors.

More recent studies have found some dramatic and pretty direct evidence of tunneling. Atanasov (2005) presents evidence of massive extraction of private benefits by controlling shareholders in Bulgarian privatizations. A subsequent paper by Atanasov et al.(2010) shows how legal protection of investors in Bulgaria reduced dilutive equity offerings and minority freezeouts. Jiang, Lee, and Yue (2010) present compelling evidence of tunneling through loans that listed Chinese firms make to their controlling shareholders, and then forgive (see also Cheung et al. 2009a). Mironov (2008) presents quite astounding evidence of tunneling through related party transactions with specifically designed special purpose entities in Russia. Overall, corporate finance seems to have converged to the standard corporate law view that investor expropriation is the main corporate governance problem.

3.4 Consequences of Shareholder Protection

Perhaps the central message of law and finance research is that legal protection of shareholders and creditors has substantial implications for the organization and development of capital markets. We begin with legal protection of shareholders.

Several studies have analyzed different aspects of shareholder protection. Better shareholder protection has been shown to increase firm valuation (Aggarwal et al. 2009; Albuquerue and Wang, 2008; Dahya, Dimitrov, and McConnell, 2008; Durnev and Kim, 2005; La Porta et al. 2002b), to increase dividends (La Porta et al. 2000), to encourage value-improving risk-taking (John, Litov, and Yeung, 2008), to increase firm access to external finance (Demirguc-Kunt and Maksimovic, 2002), to reduce earnings management (Goto, Watanabe, and Xu, 2009; Leuz, Nanda, and Wysocki, 2003), to improve governance ratings (Doidge, Karolyi, and Stulz, 2007), to increase market liquidity (Brockman and Chung, 2003; Eleswarapu and Venkataraman, 2006; Lesmond, 2005), to influence corporate cash holdings (Kalcheva and Lins, 2007; Pinkowitz, Stulz, and Williamson, 2006), to improve gains to acquirers in cross-border acquisitions (Bris, Brisley, and Cabolis, 2008; Chari, Ouimet, and Tesar, 2010; Ellis et al. 2011), and to promote the mutual fund industry (Khorana, Servaes, and Tufano, 2005, 2009) and foreign portfolio investment (Leuz, Lins, and Warnock, 2009).

An interesting group of papers in this area considers the relationship between investor protection and the efficiency of capital allocation (Almeida and Wolfenzon, 2005, 2006; Beck, Demirguc-Kunt, and Maksimovic, 2008; Beck and Levine, 2002; Braun and Larrain, 2005; Rajan and Zingales, 1998; Wurgler, 2000). Rajan and Zingales (1998) in particular pioneered an important line of research which distinguishes among industries with different levels of financial dependence, and considers the relative growth of such industries as a function of the level of financial development in a country.

Another significant strand of work looks at the so-called bonding hypothesis, the idea that a company can commit to an investor-friendly regime by cross-listing in an investor-friendly country, such as the United States. Reese and Weisbach (2002) show that equity offerings increase subsequent to cross-listing in the US, especially for firms from countries with poor shareholder protection. Doidge, Karolyi, and Stulz (2004) show that such cross-listing is associated with higher valuations, and argue that it represents a commitment to reduced investor expropriation. In a similar spirit, Doidge (2004) shows that cross-listing in the US is associated with a lower voting premium. Further evidence for the bonding hypothesis is provided by Doidge, Karolyi, and Stulz (2009), Hail and Leuz (2009), Sarkissian and Schill (2009), Lel and Miller (2008), Fernandes, Lel, and Miller (2010). Siegel (2005) however offers some contrary evidence by pointing out that the United States does not enforce its securities laws against Mexican firms cross-listed in the US, so these firms do not get all the benefits of US laws. One further finding of this research is that controllers of firms with really high private benefits of control do not wish to list in the United States (Doidge et al. 2009), and even chose to delist after the passage of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act, which further constrained tunneling. The cross-listing evidence is broadly consistent with cross-country evidence in documenting the importance of minority shareholder protection for a variety of corporate outcomes.

3.5 Ownership

One consequence of shareholder protection that has received a particularly large share of research attention is corporate ownership. In the 1980s, a few studies beginning with Demsetz and Lehn (1985) and Morck, Shleifer, and Vishny (1988) argued that the Berle-Means model of widely dispersed corporate ownership in the United States is not realistic, and that many firms in the US have concentrated ownership.3La Porta et al. (1999a) looked at a sample of large firms in 29 countries, and showed that extremely heavily concentrated corporate ownership and family control are common even among the largest firms outside the US. They further argued that ownership concentration is higher in countries with poor protection of minority shareholders. The European Corporate Governance Network (1997) and Claessens, Djankov, and Lang (2000) presented evidence on significant ownership concentration in Western Europe and East Asia, respectively. In the meantime, economists started working on the theory of concentrated corporate ownership (e.g. Almeida and Wolfenzon, 2006a, 2006b; Bebchuk, 1994; Bennedsen and Wolfenzon, 2000; Burkart, Gromb, and Panunzi, 1997; Shleifer and Vishny, 1986; Shleifer and Wolfenzon, 2002; Zingales, 1994, 1995). The theory predicts that ownership concentration should be higher in countries with weaker investor protection. Empirically, a particularly common form of concentrated ownership is control by families, often transmitted across generations. This observation has stimulated some research on the relationship between investor protection and the desire to preserve family control of firms (e.g. Bennedsen et al. 2007; Bertrand et al. 2008; Bertrand and Schoar, 2006; Burkart, Panunzi, and Shleifer, 2003).

The relationship between investor protection and ownership concentration has been tested in a number of empirical studies. Some of these studies, such as Franks and Mayer (2001) for Germany, Chernykh (2008) for Russia, and Donelli, Larrain, and Urzua (2010) for Chile, relate the evolution of ownership concentration over time to changes in investor protection in individual countries. More recent studies begin to look at the evolution of ownership concentration and its determinants (see Morck and Steier (2005) for a historical account and Fahlenbrach and Stulz (2009) for the United States). Franks, Mayer, and Rossi (2009) argue that the reduction in ownership concentration in the UK over the 20th century had little do to with investor protection. However, recent studies looking at a cross-section of countries, such as Foley and Greenwood (2010) and Franks et al. (2009) find that ownership dispersion after the IPO takes place faster in countries with better investor protection. In countries with poor investor protection, insiders sometimes reduce but sometimes increase the concentration of their ownership, depending on market conditions (Donelli et al. 2010; Kim and Weisbach, 2008. Looking at essentially the reverse experiment, Boubakri, Cosset, and Guedhami (2005) consider ownership re-concentration after privatization in 39 countries, and find that such re-concentration takes place faster in countries with poor investor protection. The empirical link between ownership concentration and investor protection thus seems broadly consistent with theoretical predictions.

Another area of analysis focuses on understanding the costs and benefits of complex ownership structures. La Porta et al. (1999a) and Almeida and Wolfenzon (2006a) suggest that complex ownership structures such as pyramids facilitate tunneling, whereas Khanna and Palepu (2000a, 2000b), and Khanna and Yafeh (2007) stress the efficiency benefits of business groups. There is some evidence pointing in each direction. Bertrand, Mehta, and Mullainathan (2002) find some evidence of tunneling in Indian business groups by looking at the propagation of an earnings shock in one group across group members. Gopalan, Nanda, and Seru (2007) show that Indian business groups transfer cash toward weaker member firms, and interpret such transfers as improving efficiency rather than reflecting tunneling. Lin et al. (2011) find that pyramidal structures increase the cost of borrowing, and interpret this as evidence of increasing risk of tunneling. More recent research has focused on endogeneity of ownership structures. Almeida et al. (2011) consider the formation of Korean chaebol through acquisition, and examine the reasons for forming different structures. They argue that the discounts in the valuation of member firms are attributable to value-destroying corporate acquisitions rather than tunneling. Masulis, Pham, and Zein (2010) likewise consider the formation of business groups, and find evidence of both entrenchment (tunneling) and internal financing as motivations. Understanding the reasons for complex ownership structures is one of the most exciting and rapidly evolving research topics in law and finance.

3.6 Consequences of Creditor Protection

As with shareholder protection, basic theory predicts that the improvement of creditor powers, either in bankruptcy or before, should improve the flow of debt capital to firms (Aghion and Bolton, 1992; Gennaioli and Rossi, 2010; Hart and Moore, 1994, 1995; Townsend, 1979). Creditor rights have been considered either in terms of legal rights in bankruptcy (LLSV, Djankov et al. 2008a), or in terms of information sharing about debtors (Djankov et al. 2007; Djankov et al. 2008a; Pagano and Jappelli, 1993). In this area as well, there has been a great deal of empirical research consistent with the view that the legal rights of creditors encourage debt markets.

Better legal protection of creditor rights has been shown to increase the size of debt markets (Djankov et al. 2007; Djankov et al. 2008a, Djankov et al. 2008b; LLSV, 1997, 1998), to improve the terms on which borrowers can raise debt finance (Bae and Goyal, 2009; Qian and Strahan, 2007), to reduce collateral requirements (Davydenko and Franks, 2008; Liberti and Mian, 2010), to increase reliance on long-term as opposed to short-term debt or trade credit (Fabbri and Menichini, 2010; Fan, Titman, and Twite, 2010), to enable affiliates of multinationals to raise more local debt (Desai, Foley, and Hines, 2004), to influence the structure of banking relationships (Barth, Caprio, and Levine, 2004; Esty and Megginson, 2003; Ongena and Smith, 2000), to increase dividend payouts (Brockman and Unlu, 2009), to influence bank risk taking (Acharya, Amihud, and Litov, 2009; Houston et al. 2010), and even to reduce corruption in bank lending to firms (Barth et al. 2009).

Some research has documented that creditor rights can also be enhanced through contracts (Bergman and Nicolaievsky, 2007). Recent empirical work by Nini, Smith, and Sufi (2007) shows that such contractual credit rights exert a substantial influence on corporate investment policy and corporate governance in the United States. Benmelech and Bergman (2011) show that both contractual and national credit protections facilitate leasing as opposed to direct ownership of airplanes across countries and airlines. The evidence on creditor rights is thus in line with that on shareholder rights in documenting a significant role of law in shaping both corporate finance and investment.

3.7 Substitute Mechanisms

In principle, there could be a variety of mechanisms that substitute for legal protection of investors and still guarantee a flow of capital to firms. For example, Gomes (2000) stresses the role of reputational mechanisms. Lerner and Schoar (2005), Bergman and Nicolaievsky (2007), and Gennaioli and Rossi (2010) emphasize the role of contracts. Pistor and Xu (2005) note the role of administrative mechanisms of investor protection in China. Some empirical studies provide support for these theories. Allen et al. (2009) describe the role of reputations and relationships in India, while Allen, Qian, and Qian (2005) present related findings for China. We agree strongly with the proposition that, in poor countries, these non-legal mechanisms provide critical substitutes for the legal system. This conclusion in no way diminishes the importance of law for formal financing mechanisms as countries grow richer.

3.8 Reforms

An important concern with the initial LLSV evidence is reverse causality: countries improve their laws protecting investors as their financial markets develop, perhaps under political pressure from those investors. If instrumental variable techniques were appropriate in this context, a two stage procedure, in which in the first stage the rules are instrumented by legal origins, would address this objection. LLSV (1997, 1998) pursue this strategy. But even if instrumental variable techniques are inappropriate because legal origin influences finance through channels other than rules protecting investors, legal origins are still exogenous, and to the extent that they shape the legal rules protecting investors, these rules cannot be just responding to market development. Moreover, this criticism in no way rejects the significance of legal origins in shaping outcomes; it speaks only to the difficulty of identifying the channel.

Recent evidence has gone beyond cross-section to look at changes in financial development in response to changes in legal rules, thereby relieving the reverse causality concerns. Greenstone, Oyer, and Vissing-Jorgensen (2006) examine the effects of the 1964 Securities Act Amendments, which increased the disclosure requirements for US over-the-counter firms. They find that firms subject to the new disclosure requirements had a statistically significant abnormal excess return of about 10% over the year and a half that the law was debated and passed relative to a comparison group of unaffected NYSE/AMEX firms (see also Bushee and Leuz, 2005). Linciano (2003) examines the impact of the Draghi reforms in Italy, which improved shareholder protection. The voting premium steadily declined over the period that the Draghi committee was in operation, culminating in a drop of 7% in the premium at the time of the passage of the law. Nenova (2006) analyzes how the control premium is affected by changes in shareholder protection in Brazil. She documents that the control value more than doubled in the second half of 1997 in response to the introduction of Law 9457/1997, which weakened minority shareholder protection. Moreover, control values dropped to pre-1997 levels when in the beginning of 1999 some of the minority protection rules scrapped by the previous legal change were reinstated. Christensen, Hail, and Leuz (2010) examine the implementation of securities regulations across European states following European Union’s capital market directives, and find that market liquidity rises and cost of capital falls as individual states implement these directives.

Turning to the evidence on credit markets, Djankov et al. (2007) show that private credit rises after improvements in creditor rights and in information sharing in a sample of 129 countries. For a sample of 12 transition economies, Haselmann, Pistor, and Vig (2010) report that lending volume responds positively to improvements in creditor rights, but they also find that changes in collateral law to be more important than changes in bankruptcy law. Visaria (2009) estimates the impact of introducing specialized tribunals in India aimed at accelerating banks’ recovery of non-performing loans. She finds that the establishment of tribunals reduces delinquency in loan repayment by between 3 and 10 percentage points.

von Lilienfeld Toal, Mookherjee, and Visaria (2010) find that reforms in India that increased banks’ ability to recover non-performing loans in the 1990s improved larger borrowers’ access to capital, but reduced that of smaller ones. Musacchio (2008a, 2008b) finds that the development of bond markets in Brazil is correlated with changes in creditors’ rights. Gamboa and Schneider (2007), in an exhaustive study of recent bankruptcy reform in Mexico, show that changes in legal rules lowered the time it takes firms to go through bankruptcy proceedings and raised recovery rates. Finally, Hyytinen, Kuosa, and Takalo (2003) look at simultaneous improvement of shareholder rights and diminution of creditor rights in Finland over the period 1980–2000, and find it to be accompanied by the shift in firm financing from debt to equity. The reform evidence points to a number of complexities on exactly which laws matter and how they work through the system, but is nonetheless broadly supportive of the broad predictions of law and finance.

3.9 Legal Rules Versus Law Enforcement

An important concern about the law and finance evidence is omitted variables—the very reason IV techniques are not suitable for identifying the channels of influence. How do we know that legal origin influences financial development through legal rules, rather than some other channel (or perhaps even other rules)? The most cogent version of this critique holds that legal origin influences contract enforcement and the quality of the judiciary, and it is through this channel that it effects financial development. Indeed, we know from La Porta et al. (1999b) and Djankov et al. (2003), and elaborate below in Table 3, common law is associated with better contract enforcement.

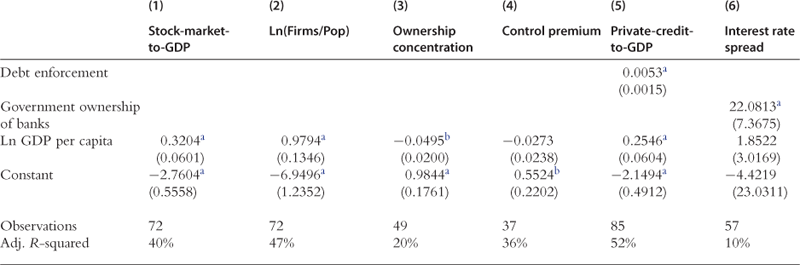

Table 2 Government regulation

Note: Variable definitions and data sources are given in the Appendix.

aSignificant at the 1% level.

bSignificant at the 5% level.

cSignificant at the 10% level.

Table 3 Judicial institutions

Note: Variable definitions and data sources are given in the Appendix.

aSignificant at the 1% level.

bSignificant at the 5% level.

cSignificant at the 10% level.

This objection is significant since, in reality, enforcement and rules are not entirely separable. A formalistic judiciary might be better able to enforce bright line rules than broad legal standards; a more flexible judiciary might have a comparative advantage at enforcing standards. One way to address this concern is to control for contract enforcement as best we can. In the regressions in Table 1, we control for per capita income, which is a crude proxy of the quality of the judiciary. More recent studies, such as Djankov et al. (2008b) and La Porta et al. (2006), also control for the quality of contract enforcement using a measure developed by Djankov et al. (2003), with the result that both the actual legal rules and the quality of contract enforcement matter. For the case of credit markets, Safavian and Sharma (2007) show that creditor rights benefit debt markets if the country has a good enough court system, but not if it does not. Djankov et al. (2008a) combine the rules and their actual enforcement into an integrated measure of debt enforcement efficiency. This measure (see Table 1 above) is highly predictive of debt market development. Importantly, the studies of reform of rules show that these changes have impact on their own. The available evidence thus suggests that both good rules and their enforcement matter, and that the combination of the two is generally most effective.

Another relevant distinction is between legal rules and their interpretation. One view is that the actual legal rules, which might have come from legislation, from appellate decisions, or from legislation codifying previous appellate decisions, are shaped by legal origins and in turn shape finance. For example, the extensive approval and disclosure procedures for self-dealing transactions discourage them in common law countries, as compared to the French civil law countries (Djankov et al. 2008b; La Porta et al. 2006). Other writers emphasize the flexibility of judicial decision-making under common law. One version of this argument suggests that common law judges are able or willing to enforce more flexible financial contracts, and that such flexibility promotes financial development (Gennaioli, 2011). Lerner and Schoar (2005) and Bergman and Nicolaievsky (2007) present some evidence in support of this view. Pistor (2006) presents a legal and historical account of the greater contractual flexibility in common law, the reason being that contractual freedom is unencumbered by social conditionality.4

A second version of the flexibility thesis stresses the ability of common law courts to use broad standards rather than specific rules in rendering their decisions. This ability enables judges to “catch” self-dealing or tunneling, and thereby discourages it. Coffee (1999) has famously called this the smell-test of common law. Johnson, La Porta, et al. (2000) examine several legal cases concerning tunneling of assets by corporate insiders in civil law countries, and find that the bright line rules of civil law allow corporate insiders to structure legal transactions that expropriate outside investors. In contrast, the broader standards of common law, such as fiduciary duty, discourage tunneling more effectively.

At this point, there is evidence supporting both the “laws on the books” and the “judicial flexibility” theories. As we argue in Section 4, both interpretations are also consistent with the fundamental differences between common and civil law.

3.10 Legal Origins Beyond Finance

Research on the effects of legal origins on legal rules, and the consequences of those for economic outcomes, has gone far beyond finance. Here we discuss this research only briefly; it is covered more extensively in La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer (2008).

Several papers consider government regulation, or even ownership, of particular economic activities. Djankov et al. (2002) look at the number of steps an entrepreneur must complete in order to begin operating a business legally, a number that in 1999 ranged from 2 in Canada and New Zealand to 22 in the Dominican Republic. They examine the impact of such entry regulation on corruption and the size of the unofficial economy. Botero et al. (2004) construct indices of labor market regulation and examine their effect on labor force participation rates and unemployment. Djankov et al. (2003) examine government ownership of the media, which remains extensive around the world, particularly for television. Mulligan and Shleifer (2005a, 2005b) look at one of the ultimate forms of government intervention in private life, military conscription.

Table 2 presents the results on regulation in a similar format to Table 1. Higher income per capita is correlated with lower entry regulation and government ownership of the media, but not with labor regulation or conscription (Panel A). Both French and German civil origins have more entry and labor regulation, higher state ownership of the media, and heavier reliance on conscription.5 The coefficients imply that, compared to common law, French legal origin is associated with an increase of 0.69 in the (log) number of steps to open a new business (which ranges from 0.69 to 3.0), a rise of 0.26 in the index of labor regulation (which ranges from 0.15 to 0.83), a 0.21 rise in government ownership of the media (which ranges from 0 to 1), and a 0.55 increase in conscription (which ranges from 0 to 1).

According to the estimated coefficients in Panel B, a two-standard deviation increase in the (log) number of steps to open a new business is associated with a 0.71 worsening of the corruption index and a 14 percentage point rise in employment in the unofficial economy. The corruption index ranges from −1.61 to 2.39, with the higher score indicating less corruption. A two-standard deviation increase in the regulation of labor implies a 1.99 percentage point reduction in the male labor force participation rate, a 2.32 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate, and a 5.67 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate of young males.

One final category of papers investigates the effects of legal origins on the characteristics of the judiciary (and other government institutions), and then the effect of those on the security of property rights and contract enforcement. Djankov et al. (2003) look at the formalism of judicial procedures in various countries, and its effect on the time it takes to evict a non-paying tenant or to collect a bounced check. This variable can be interpreted more broadly as the efficiency of contract enforcement by courts, and in fact turns out to be highly correlated with the efficiency of debt collection obtained in an entirely different way by Djankov et al. (2008a). La Porta et al. (2004) adopt a very different strategy and collect information from national constitutions on judicial independence (as measured by judicial tenure) and the acceptance of appellate court rulings as a source of law. They then ask directly whether judicial independence contributes to the quality of contract enforcement and the security of property rights.

Table 3 shows the results on judicial institutions. Higher income per capita is associated with less legal formalism but not with longer judicial tenure or the acceptance of case law (Panel A). Here again, legal origin has a pronounced effect on institutions. Compared to common law countries, civil law countries generally have more legal formalism, lower judicial tenure, and sharply lower constitutional acceptance of case law. The estimated coefficients imply that French legal origin is associated with an increase of 1.49 in the index of legal formalism, a reduction of 0.24 in judicial tenure, and of 0.67 in case law. These are large effects since legal formalism ranges from 0.73 to 6.0, and both judicial tenure and case law range from 0 to 1.

Judicial institutions matter for both the efficiency of contract enforcement and the security of property rights (Panel B). The estimated coefficients imply that a two-standard deviation increase in legal formalism is associated with a 65 percentage point increase in the time to collect on a check and a reduction of 1.1 in the index of contract enforcement (the latter ranges from 3.5 to 8.9). Moreover, a two-standard deviation increase in judicial tenure is associated with a 2.9 point rise in the property rights index. Finally, a two-standard deviation increase in case law is associated with an improvement of 1.3 points in the property rights index, which ranges from 1 to 5.

3.11 Summary

So, what do we learn from these tables? The economic consequences of legal origins are pervasive. Compared to French civil law, common law is associated with (a) better investor protection, which in turn is associated with improved financial development, better access to finance, and higher ownership dispersion; (b) lighter government ownership and regulation, which are in turn associated with less corruption, better functioning labor markets, and smaller unofficial economies; and (c) less formalized and more independent judicial systems, which are in turn associated with more secure property rights and better contract enforcement. The most important aspect—as well as challenge—of these results is how pervasive is the influence of legal origins. We address some of the concerns about our evidence later, but first try to explain the facts.

4 Explaining the Facts

The correlations between legal origins, legal and regulatory rules, and economic outcomes documented in the previous section require an explanation. LLSV (1997, 1998) do not advance such an explanation, although in a broader study of government institutions, LLSV (1999b) follow Hayek (1960) and suggest that common law countries are more protective of private property than French legal origin ones. In the ensuing years, many academics, ourselves included, used the historical narrative to provide a theoretical foundation for the empirical evidence (see Djankov et al. 2003; Glaeser and Shleifer, 2002; Mulligan and Shleifer, 2005b). In this section, we begin with the alternative historical explanations, and then try to revise, synthesize, and advance previous theoretical accounts into the Legal Origins Theory.6

4.1 Explanations Based on Revolutions

The standard explanation of the differences between common law and French civil law in particular, and to a lesser extent German law, focus on 17th–19th century developments (Klerman and Mahoney, 2007; Merryman, 1969; Zweigert and Kötz, 1998). According to this theory, the English lawyers were on the same winning side as the property owners in the Glorious Revolution, and in opposition to the Crown and to its courts of royal prerogative. As a consequence, the English judges gained considerable independence from the Crown, including lifetime appointments in the 1701 Act of Settlement. A key corollary of such independence was the respect for private property in English law, especially against possible encroachments by the sovereign. Indeed, common law courts acquired the power to review administrative acts: the same principles applied to the deprivation of property by public and private actors (Mahoney, 2001, p. 513). Another corollary is respect for the freedom of contract, including the ability of judges to interpret contracts without a reference to public interest (Pistor, 2006). Still another was the reassertion of the ability of appellate common law courts to make legal rules, thereby becoming an independent source of legal change separate from Parliament. Judicial independence and law making powers in turn made judging a highly attractive and prestigious occupation.

In contrast, the French judiciary was largely monarchist in the 18th century (many judges bought offices from the king), and ended up on the wrong side of the French Revolution. The revolutionaries reacted by seeking to deprive judges of independence and law making powers, to turn them into automata in Napoleon’s felicitous phrase. Following Montesquieu’s (1748) doctrine of separation of powers, the revolutionaries proclaimed legislation as the sole valid source of law, and explicitly denied the acceptability of judge-made law. “For the first time, it was admitted that the sovereign is capable of defining law and of reforming it as a whole. True, this power is accorded to him in order to expound the principles of natural law. But as Cambaceres, principal legal adviser to Napoleon, once admitted, it was easy to change this purpose, and legislators, outside of any consideration for ‘natural laws’ were to use this power to transform the basis of society” (David and Brierley, 1985, p. 60).

Hayek (1960) traces the differences between common and civil law to distinct conceptions of freedom. He distinguishes two views of freedom that are directly traceable to the predominance of an essentially empiricist view of the world in England and a rationalist approach in France. “One finds the essence of freedom in spontaneity and the absence of coercion, the other believes it to be realized only in the pursuit and attainment of an absolute social purpose; one stands for organic, slow, self-conscious growth, the other for doctrinaire deliberateness; one for trial and error procedure, the other for the enforced solely valid pattern (p. 56).” To Hayek, the differences in legal systems reflect these profound differences in philosophies of freedom.

To implement his strategy, Napoleon promulgated several codes of law and procedure intended to control judicial decisions in all circumstances. Judges became bureaucrats employed by the State; their positions were seen as largely administrative, low-prestige occupations. The ordinary courts had no authority to review government action, making them useless as guarantors of property against the state.

The diminution of the judiciary was also accompanied by the growth of the administrative, as Napoleon created a huge and invasive bureaucracy to implement the state’s regulatory policies (Woloch, 1994). Under Napoleon, “the command orders were now unity of direction, hierarchically defined participation in public affairs, and above all the leading role assigned to the executive bureaucracy, whose duty was to force the pace and orient society through the application from above of increasingly comprehensive administrative regulations and practices” (Woolf, 1992, p. 95).

Merryman (1969, p. 30) explains the logic of codification: “If the legislature alone could make laws and the judiciary could only apply them (or, at a later time, interpret and apply them), such legislation had to be complete, coherent, and clear. If a judge were required to decide a case for which there was no legislative provision, he would in effect make law and thus violate the principle of rigid separation of powers. Hence it was necessary that the legislature draft a code without gaps. Similarly, if there were conflicting provisions in the code, the judge would make law by choosing one rather than another as more applicable to the situation. Hence there could be no conflicting provisions. Finally, if a judge were allowed to decide what meaning to give to an ambiguous provision or an obscure statement, he would again be making law. Hence the code had to be clear.”

Yet, according to Merryman (1996), Napoleon’s experiment failed in France, as the notion that legislation can foresee all future circumstances proved unworkable. Over decades, new French courts were created, and they as well as older courts increasingly became involved in the interpretation of codes, which amounted to the creation of new legal rules. Even so, the law-making role of French courts was never explicitly acknowledged, and never achieved the scope of their English counterparts.

Perhaps more importantly for cross-country analysis, the developing countries into which the French legal system was transplanted apparently adhered faithfully to the Napoleonic vision. In those countries, judges stuck to the letter of the code, resolving disputes based on formalities even when the law needed refinement. Enriques (2002) shows that, even today, Italian magistrates let corporate insiders expropriate investors with impunity, as long as formally correct corporate decision-making procedures are followed. Spamann (2009a) documents the literal incorporation of legal materials and models from the respective legal families’ core countries in treatises and law reform projects in 32 peripheral and semi-peripheral countries in recent years. In the transplant and to some extent even in the origin countries, legislation remained, at least approximately, the sole source of law, judicial law-making stayed close to non-existent, and judges retained their bureaucratic status. Merryman memorably writes that “when the French exported their system, they did not include the information that it really does not work that way, and failed to include the blueprint of how it actually does work” (1996, p. 116). This analysis of the “French deviation” may explain the considerable dynamism of the French law as compared to its transplant countries, where legal development stagnated. The French emphasis on centralized bureaucratic control may have been the most enduring influence of transplantation.

Although less has been written about German law, it is fair to say that it is a bit of a hybrid (Dawson, 1960, 1968; Merryman, 1969; Zweigert and Kötz, 1998). Like the French courts, German courts had little independence. However, they had greater power to review administrative acts, and jurisprudence was explicitly recognized as a source of law, accommodating greater legal change.

The historical analysis has three key implications for the economic consequences of legal origins. First, the built-in judicial independence of common law, particularly in the cases of administrative acts affecting individuals, suggests that common law is likely to be more respectful of private property and contract than civil law.

Second, common law’s emphasis on judicial resolution of private disputes, as opposed to legislation as a solution to social problems, suggests that we are likely to see greater emphasis on private contracts and orderings, and less emphasis on government regulation, in common law countries. To the extent that there is regulation, it aims to facilitate private contracting rather than to direct particular outcomes. Pistor (2006) describes French legal origin as embracing socially conditioned private contracting, in contrast to common law’s support for unconditioned private contracting. Damaška (1986) calls civil law “policy-implementing”, and common law “dispute resolving”.

Third, the greater respect for jurisprudence as a source of law in the common law countries, especially as compared to the French civil law countries, suggests that common law will be more adaptable to the changing circumstances, a point emphasized by Hayek (1960) and more recently Levine (2005). These adaptability benefits of common law have also been noted by scholars in law and economics (Gennaioli and Perotti, 2010; Ponzetto and Fernandez, 2008; Posner, 1973; Priest, 1977; Rubin, 1977), who have made the stronger claim that through sequential decisions by appellate courts, common law evolves not only for the better, but actually toward efficient legal rules. The extreme hypothesis of common law’s efficiency is difficult to sustain either theoretically or empirically, but recent research does suggest that the ability of judges to react to changing circumstances—the adaptability of common law—tends to improve the law’s quality over time. For example, Gennaioli and Shleifer (2007) argue in the spirit of Cardozo (1921) and Stone (1985) that the central strategy of judicial law-making is distinguishing cases from precedents, which has an unintended benefit that the law responds to a changing environment. The quality of law improves on average even when judges pursue their policy preferences; law making does not need to be benevolent.

The theoretical research on the adaptability of common law has received some empirical support in the work of Beck, Demirguc-Kunt, and Levine (2003), who show that the acceptability of case law variable from La Porta et al. (2004) captures many of the benefits of common law for financial and other outcomes. On the other hand, a recent study of the evolution of legal doctrine governing construction disputes in the US over the period of 1970–2005 finds little evidence either that legal rules converge over time, or that they move toward efficient solutions (Niblett, Posner, and Shleifer, 2010).

4.2 Explanations Based on Medieval Developments

The idea that the differences between common and civil law manifest themselves for the first time during the Enlightenment seems a bit strange to anyone who has heard of Magna Carta. Some of the differences were surely sharpened, or even created, by the English and the French Revolutions. For example, judges looked to past judicial decisions for centuries in both England and France prior to the revolutions (Gorla and Moccia, 1981). However, the explicit reliance on precedent as a source of law (and the term precedent itself) is only a 17th and 18th century development in England (Berman, 2003). Likewise, the denial of the legal status of precedent in France is a Napoleonic rather than an earlier development.

But in other respects, important differences predate the revolutions. The English judges fought the royal prerogative, used juries to try criminal cases, and pressed the argument that the King (James) was not above the law early in the 17th century. They looked down on the inquisitorial system that flourished on the Catholic continent. In light of such history, it is hard to sustain the argument that the differences between common and civil law only emerged through revolutions.

Several distinguished legal historians, including Dawson (1960) and Berman (1983), trace the divergence between French and English law to a much earlier period, namely the 12th and 13th centuries. According to this view, the French Crown, which barely had full control over the Ile de France let alone other parts of France, adopted the bureaucratic inquisitorial system of the Roman Church as a way to unify and perhaps control the country. The system persisted in this form through the centuries, although judicial independence at times increased as judges bought their offices from the Crown. Napoleonic bureaucratization and centralization of the judiciary is seen as a culmination of a centuries-old tug of war between the center and the regions.

England, in contrast, developed jury trials as far back as the 12th century, and enshrined the idea that the Crown cannot take the life or property of the nobles without due process in the Magna Carta in 1215. The Magna Carta stated: “No freeman shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined, nor will we go or send against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” The Magna Carta established the foundations of the English legal order. As in France, such independence was continuously challenged by the Crown, and the courts of royal prerogative, subordinate to the Crown, grew in importance in the 16th century, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth. Yet, as we indicated earlier, even during Elizabeth’s reign, and much more so during those of James I and Charles I, Parliament and courts repeatedly reaffirmed the rights of individuals against royal demands. Chief Judge Edward Coke’s early 17th century insistence that the king is not above the law is neither a continental nor a post-revolutionary phenomenon. The Glorious Revolution eliminated the courts of royal prerogative, and eventually enshrined the principles of judicial independence in several acts of Parliament.

Glaeser and Shleifer (2002) present a theoretical model intended to capture this comparative 12th and 13th century narrative, but with an economic twist. They argue that England was a relatively peaceful country during this period, in which decentralized dispute resolution on the testimony of independent knights (juries) was efficient. France was a less peaceful country, in which high nobles had the power to subvert decentralized justice, and hence a much more centralized system, organized, maintained, and protected by the sovereign, was required to administer the law. Roman law provided the backbone of such a system. This view sees the developments of 17th and 18th centuries as reinforcing the structures that evolved over the previous centuries.

Regardless of whether the revolutionary or the medieval story is correct, they have very similar empirical predictions. In the medieval narrative, as in the revolutionary one, common law exhibits greater judicial independence than civil law, as well as greater sympathy of the judiciary toward private property and contract, especially against infringements by the executive. In both narratives, judicial law making and adaptation play a greater role in common than in civil law, although this particular difference might have been greatly expanded in the Age of Revolutions. The historical accounts may differ in detail, but they lead to the same place as to the fundamental features of law. These features, then, carry through the process of transplantation, and appear in the differences among legal families.

4.3 Legal Origins Theory

Legal Origins Theory has three basic ingredients. First, regardless or whether the medieval or the revolutionary narrative is the best one, by the 18th or 19th centuries England and Continental Europe, particularly France, have developed very different styles of social control of business, and institutions supporting these styles. Second, these styles of social control, as well as legal institutions supporting them, were transplanted by the origin countries to most of the world, rather than written from scratch. Third, although a great deal of legal and regulatory change has occurred, these styles have proved persistent in addressing social problems.

Djankov et al. (2003) propose a particular way of thinking about the alternative legal styles. All legal systems seek to simultaneously address twin problems: the problem of disorder or market failure, and the problem of dictatorship or state abuse. There is an inherent trade-off in addressing these twin problems: as the state becomes more aggressive in dealing with disorder, it may also become more abusive. We can think of the French civil law family as a system of social control of economic life that is relatively more concerned with disorder, and relatively less with dictatorship, in finding solutions to social and economic problems. In contrast, the common law family is relatively more concerned with dictatorship, and less with disorder. These are the basic attitudes or styles of the legal and regulatory systems, which influence the “tools” they use to deal with social concerns. Of course, common law does not mean anarchy, as the government has always maintained a heavy hand of social control; nor does civil law mean dictatorship. Indeed, both systems seek a balance between private disorder and public abuse of power. But they seek it in different ways: common law by shoring up markets, civil law by restricting them or even replacing them with state commands.

Legal Origins Theory raises the obvious question of how the influence of legal origins has persisted over the decades or even centuries. Why so much hysteresis? What is it that the British brought on the boat that was so different from what the French or the Spaniards brought, and that had such persistent consequences? The key point to realize is that transplantation involves not just specific legal rules (many of which actually change later), but also legal institutions (of which judicial independence might be the most important), human capital of the participants in the legal system, and crucially the strategy of the law for dealing with new problems. Successive generations of judges, lawyers, and politicians all learn the same broad ideas of how the law and the state should work. The legal system supplies the fundamental tools for addressing social concerns, and it is that system, as defined by Zweigert and Kötz, with its codes, distinctive institutions, modes of thought and even ideologies, that is very slow to change.