Chapter 1

Securitization*

Abstract

Keywords

Securitization; Capital Markets; Asset-Backed Securities; Financial Crisis

JEL classifications

G1; G2; E40

1 Introduction

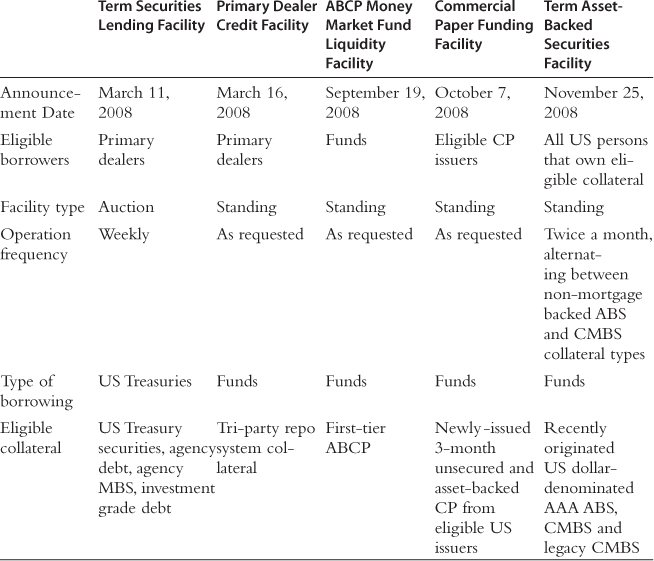

Prior to the financial crisis of 2007–2008, securitization was a very large part of US capital markets. It played a central role in the recent financial crisis. Yet it is largely unregulated and it is not well understood. There is little research on this topic. In this paper, we survey the literature on securitization and summarize the outstanding questions.

Traditionally, financial intermediaries originated loans that they then held on their balance sheets until maturity. This is no longer the case. Starting around 1990, pools of loans began to be sold in capital markets, by selling securities linked to pools of loans held by legal entities called “special purpose vehicles” (SPVs). These securities, known as asset-backed securities (ABS) (or mortgage-backed securities (MBS), in the case where the loans are mortgages) are claims to the cash flows from the pool of loans held by the SPV. Such securities can be issued with different seniorities, known as tranches. Securitization has fundamentally altered capital markets, the functioning of financial intermediation, and challenges many theories of the role of financial intermediaries.

Securitization has an important role in the US economy. As of April 2011, there was $11 trillion of outstanding securitized assets, including residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), other ABS, and asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP). This is substantially more than the size of all outstanding marketable US Treasury securities—bonds, bills, notes, and TIPS combined.1 A large fraction of consumer credit in the US is financed via securitization. It is estimated that securitization has funded between 30% and 75% of lending in various consumer lending markets, and about 64% of outstanding home mortgages.2 In total, securitization has provided over 25% of outstanding US consumer credit.3

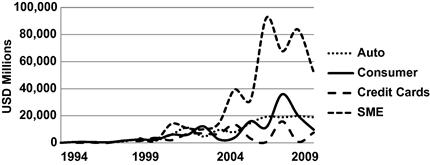

Figure 1 shows the US issuance amounts of private securitization and corporate bonds. In 2002 the amounts of securitized bonds issued ($662.4 billion) exceeded corporate bond issuance ($636.7 billion) for the first time, and continued to be larger until the financial crisis. Figure 1 includes non-agency, i.e. private, mortgage securitizations. But, even when this very large category is removed, securitization is very significant, as shown in Figure 2. The main categories of loans securitized, aside from mortgages, are credit card receivables, automobile loans, and student loans. US non-mortgage securitization issuance exceeded US corporate bond issuance in 2005, and then plummets during the financial crisis. Figure 3 shows US mortgage-related securitization, including agency bonds, residential-mortgage-backed securities (RMBS), and commercial-mortgage-backed securitization (CMBS). Securitization has grown significantly in other countries, as well. The total European securitization issuance grew from $302 million in 1992 to a peak of $1.1 billion in 2008, falling to $512 million after the crisis. Figure 4 shows the amounts of European issuance of some of the major categories of non-mortgage securitization.

Figure 1 US Corporate debt issuance vs. US non-agency securitization issuance.

Figure 2 Non-mortgage Abs issuance vs. corporate debt issuance.

Figure 3 US Mortgage related securities issuance

Figure 4 European issuance of selected non-mortgage ABS.

Securitization is not only important because it is quantitatively significant. It also challenges theoretical notions of the role of financial intermediation. Financial intermediaries make loans to customers, loans that traditionally were held on their balance sheets until maturity. They did this to ensure themselves an incentive, so the theory goes, to screen borrowers and to monitor them during the course of the loan. The logic of the argument is that, were banks not to hold the loans, then they would not screen or monitor. Providing the banks with these incentives explained the nonmarketability of bank loans. Many firms, however, issue bonds, which do not involve banks and the associated screening and monitoring, so somehow it is possible for banks to be successfully avoided. Securitization blurs the line between bonds and loans, suggesting that the traditional arguments about screening and monitoring were not correct, or that the world has changed in some important way.

Despite the quantitative and theoretical importance of securitization, there is relatively little research on the subject. In addition, the recent financial crisis centered on securitization, so the imperative to understand it is paramount. The central motivations for securitization are often driven by institutional details in law, accounting, and regulation, so it is necessary to start with some of these details. Section 2 provides an overview of the legal structure of securitization and a brief example of a specific securitization. Section 3 gives summary statistics on the growth and performance of various types of securitized vehicles, illustrating the rapid transformation of financial intermediation in the last 25 years.

To go from the old world of finance to the new world of securitization, a bank must decide to move some loans off its balance sheet into a legal entity generically known as a special purpose vehicle (SPV). This decision is driven by the relative cost of capital in the two places, and this cost of capital is itself determined by a wide variety of factors. In Section 4, we survey the literature on these factors and present a simple model of the private decision to securitize, driven by such factors as bankruptcy costs, taxes, and the convenience yield (if any) of bank deposits and securitized bonds. Section 5 explores several hypotheses to explain the rise of securitization over the last three decades, focusing on the changes in the banking sector and on how those changes may have affected the parameters of the Section IV model.

The Section IV model considers a full-information ideal and abstracts from the asymmetric information costs if investors perceive that securitized loans are improperly screened or suffer from a lemons problem. The market deals with these costs using a variety of security designs and contractual features, the source of the largest current literature on securitization. Section 6 summarizes the theory papers in this literature, and Section 7 summarizes the empirical papers. Section 8 takes up the social costs and benefits of securitization, surveying a small literature on the role of securitization on monetary policy, financial stability, and financial regulation. Section 9 concludes with a summary of what we know and lays out a set of important open questions.

2 Securitization: Some Institutional Details

In this section we begin with an overview of the legal structure of securitization. Then we provide a brief discussion of an example, the Chase Issuance Trust, for securitizing credit card receivables. Finally, we consider some other related forms of securitization.

2.1 Legal Structure

“Securitization” means selling securities whose principal and interest payments are exclusively linked to a pool of legally segregated, specified, cash flows (promised loan payments) owned by a special purpose vehicle (SPV). The cash flows were originated (“underwritten”) by a financial intermediary, which sold the rights to the cash flows to the special purpose vehicle. The securities, called “asset-backed securities” (ABS), are rated and sold in the capital markets. Historically, the financial intermediary would have held the loans on-balance sheet until maturity. But, with securitization, the loans can be financed off-balance sheet.

Figure 5 shows a simplified overview of the securitization process. The originating firm is at the top of the figure. This firm, a financial intermediary, employs lending officers and actively engages in the process of finding lending opportunities. Whether a potential borrower represents a good lending opportunity or not is the primary decision that this intermediary must make. It determines underwriting criteria or lending standards, and proceeds to make loans. These loans must be funded, and they can be funded by the intermediary borrowing, or by selling the loans to a “special purpose vehicle” (SPV), which is a legally separate legal entity. In the figure this entity is labeled “Master Owner Trust.” This SPV is not an operating entity. Indeed, no one works there and it has no physical location. Instead, it is an artificial firm that functions according to pre-specified rules, and it contractually outsources the servicing of the loans.

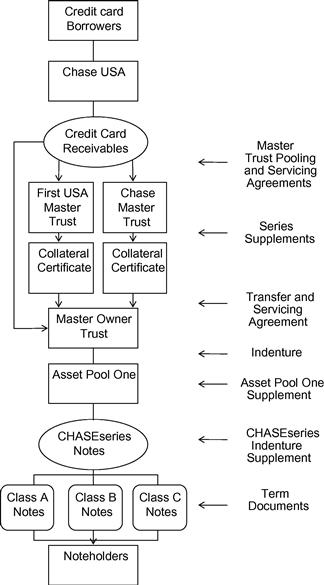

Figure 5 Overview of securitization.

The SPV purchases the loan cash flows by selling securities based on seniority, called “tranches”, to investors in the capital markets, shown at the bottom of the figure. These securities are claims that are linked to the cash flows of the portfolio of loans that the SPV then purchases from the operating firm (the intermediary). The cash flows are passive in the sense that the underwriting decision has already been made, so there is nothing further to do except wait to see if the cash flows are repaid as promised.

2.2 Securitization Example: Credit Card Securitization via the Chase Issuance Trust

To illustrate some of the important features of securitization that we will subsequently focus on, it is useful to very briefly examine an actual example. For this purpose we will look at the Chase Issuance Trust, which is the JP Morgan Chase master trust for the securitization of credit card receivables underwritten by First USA and Chase USA. Chase merged with First USA in 2005, so credit card receivables can come from Chase or from the old First USA bank. The entity, Chase Issuance Trust, is a special purpose vehicle that periodically receives/buys credit card receivables and issues securities in the capital markets. We will highlight the important features of the structure, which are basically common to all securitizations.

The structure of the securitization is shown in Figure 6. The box labeled “Master Owner Trust” is what the deal documents refer to as “Chase Issuance Trust”. The figure shows the various special purpose vehicles and participants in the securitization. Along the right-hand side of the figure are the governing legal documents corresponding to each part of the structure. At the very top of the figure are the consumers who have borrowed money on their credit cards, as customers of Chase Bank. Chase transfers/sells the receivables, depending on whether they were originated in the First USA or Chase bank to one of two master trusts, either First USA Master Trust or Chase Master Trust.

Figure 6

There is a two-tiered structure. Each of First USA Master Trust and Chase Master Trust is a special purpose vehicle, a trust. A business trust is a separate legal entity, created under a state’s business trust law (see Schwarcz (2003)). Each of these trusts is able to purchase the receivables by selling collateral certificates representing interests in the cash flows that credit card holders are obligated to pay to the Master Owner Trust–Chase Issuance Trust. Chase Issuance Trust issues securities in the capital markets called CHASEseries Notes that are differentiated by seniority, with Class A notes being the most senior (AAA/Aaa) and Class C notes the most junior of the publicly issued notes. In the figure, these notes are linked to one specific vintage of credit card receivables, called “Asset Pool One”. Periodically, different pools of receivables are sold by Chase USA to the trusts, with different series of securities periodically issued that are contractually linked to the various pools. Securities issues by Chase Issuance Trust to capital market participants are generically known as asset-backed securities.

The structure involves multiple special purpose vehicles, which are legal entities, but not really operating companies, as there are no decisions to be made. In this example, Chase Issuance Trust is a Delaware statutory trust, a separate legal entity that is an unincorporated association governed by a trust agreement under which management is delegated to a trustee. The master trusts’ activities are limited to (according to the Prospectus Supplement dated May 12, 2005):

• Acquiring and holding collateral certificates, credit card receivables, and the other assets of the master trust and the proceeds from those assets;

• Making payments on the notes;

• Engaging in other activities that are necessary or incidental to accomplishing these limited purposes, which activities cannot be contrary to the status of the master owner trust as a “qualifying special purpose entity” under existing accounting literature.4

The trust makes no managerial decisions, but simply executes rules that are written down in the contracts.

As indicated in Figure 6, the mechanics of collecting payments from the credit card holders, monitoring them, distributing payments to note holders, and so on, is outsourced via “pooling and servicing” contracts and trustees. Servicers perform the necessary tasks needed to enforce and implement the debt contracts with respect to cash flows, while trustees monitor adherence to indentures.

There are three important features to the securitization structure. First, the SPV is tax neutral; second, the SPV is liquidation-efficient in that it avoids bankruptcy; and third, that it is bankruptcy remote from the sponsor—Chase in this example. The SPVs used in securitization, whether they are trusts, limited liability corporations, or limited partnerships can be structured so that they qualify for “pass through” tax treatment with regard to state and federal income tax purposes. This avoids income tax at the entity level. The debt issued by the SPV is then not tax advantaged, as is on-balance sheet debt issued by the sponsor. This means that the sponsor’s decision about on- versus off-balance sheet financing has an important tax dimension.

Bankruptcy by an SPV is an event that effectively cannot occur; we call this liquidation-efficient. Under US law, private contracts cannot simply agree to avoid government bankruptcy rules, but private contracts can be written so as to minimize this possibility. While we discuss more of the details later, here we note the most important, namely, what happens if the underlying pool of securitized loans does not pay off enough to contractually honor the coupon payments to the note holders. Normally, under a debt contract, if note holders are not paid what has been contractually promised them, then they can force the borrowers into Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Importantly, that does not happen with asset-backed securities.

According to the prospectus, events of default include:

• The master owner trust’s failure, for a period of 35 days, to pay interest on any series, class or tranche of notes when that interest becomes due and payable;

• The master owner trust’s failure to pay the stated principal amount of any series, class, or tranche of notes on the applicable legal maturity date for that series, class, or tranche;

• The master owner trust’s default in the performance, or breach, of any other of its covenants or warranties in the indenture for a period of 90 days after either the indenture trustee or the holders of at least 25% of the aggregate outstanding dollar principal amount of the outstanding notes of the affected series, class, or tranche has provided written notice requesting the remedy of that breach, if, as a result of that default, the interests of those noteholders are materially and adversely affected and continue to be materially and adversely affected during that 90-day period;

• The occurrence of certain events of bankruptcy or insolvency of the master owner trust; and

• With respect to any series, class, or tranche of notes, any additional events of default specified in the accompanying prospectus supplement.

An event of default, however, does not trigger bankruptcy. If the SPV cannot pay the contractually obligated coupons, it declares an “early amortization event”. The contract states that:

It is not an event of default if the issuing entity fails to redeem a series, class or tranche of notes prior to the legal maturity date for those notes because it does not have sufficient funds available or if payment of principal of a class or tranche of subordinated notes is delayed because that class or tranche is necessary to provide required subordination for senior notes.

After an event of default and acceleration of a tranche of notes, funds on deposit in the applicable issuing entity bank accounts for the affected notes will be applied to pay principal of and interest on those notes. Then, in each following month, available principal collections and available finance charge collections allocated to those notes will be deposited into the applicable issuing entity bank account and applied to make monthly principal and interest payments on those notes until the earlier of the date those notes are paid in full or the legal maturity date of those notes. However, subordinated notes will receive payment of principal prior to their legal maturity date only if, and to the extent that, funds are available for that payment and, after giving effect to that payment, the required subordination will be maintained for senior notes. (Chase Issuance Trust Prospectus (May 12, 2005), p. 8)

Thus, contractually there is a living will for the SPV. In particular, if the underlying pool cannot pay the contractual coupons owed to holders of the asset-backed securities, the contractual remedy is to use the available funds to start paying down principal early. Other early amortization events include the following (among other events):

• For any month, the three-month average of the Excess Spread Percentage is less than zero;

• The issuing entity fails to designate additional collateral certificates or credit card receivables for inclusion in the issuing entity or Chase USA fails to increase the investment amount of an existing collateral certificate;

• Any Issuing Entity Servicer Default occurs that would have a material adverse effect on holders of the notes;

• The occurrence of an event of default and acceleration of a class of tranche of notes.

The “excess spread” refers to the difference between what the underlying portfolio of loans yields in a month minus the amounts owed to note holders in that month (the coupon payments), the monthly servicing fee (paid to the servicer of the loans) and any realized losses on the loans.

Bankruptcy remoteness refers to the effect of the possible bankruptcy of Chase, the originator/sponsor, on the assets held by the SPV. The potential problem is that the claimants on the sponsor, Chase, could in bankruptcy seek to recover the assets that were “sold” to the securitization SPV.5 In the early days of securitization there was some confusion about the necessary accounting steps needed to ensure that the receivables had, in fact, been sold to the SPV, rather than constituting a secured loan. To clarify this, FASB required a two-step approach, like the one shown in Figure 6. This is known as the “Norwalk two-step” because FASB is located in Norwalk, Connecticut. As we discuss later, case law has to date upheld the bankruptcy remoteness of securitization SPVs.

In the very early days of securitization, each time a pool of loans was securitized, a new SPV had to be set up. Later, the master trust became the main vehicle and different vintages of loan pools were sold to the same trust, with securities issued by the SPV as needed, corresponding to each vintage of loan pool. Figure 7 shows the outstanding receivables in the Chase Issuance Trust over time. It varies as new vintages of loans are sold to the SPV, while older vintages mature.

Figure 7 Chase issuance trust: outstanding principal receivables.

The Pooling and Servicing Agreement describes the eligible loans that can be sold into the trust periodically, in this case credit card receivables. The agreement states that:

Chase USA has the right, subject to certain limitations and conditions described in the transfer and servicing agreement, to designate from time to time additional consumer revolving credit card accounts and to transfer to the issuing entity all credit card receivables arising in those additional credit card accounts, whether those credit card receivables are then existing or thereafter created. Any additional consumer revolving credit card accounts designated must be Issuing Entity Eligible Accounts as of the date the transferor designates those accounts to have their credit card receivables transferred to the issuing entity and must have been selected as additional credit card accounts absent a selection procedure believed by Chase USA to be materially adverse to the interests of the holders of notes secured by the assets of the issuing entity. (Emphasis added.)

It is the job of the trustee and of the rating agencies to ensure that new loans sold to the trust satisfy the contractual criteria for eligibility. The contract specifies the eligibility criteria for loans to be securitized. The italicized part of the agreement above provides that, at least contractually, if the eligibility criteria are not fine enough to prevent adverse selection, then there will be ex post recourse.

2.3 Other Forms of Securitization

This survey focuses on securitization, the process of moving pools of loans off-balance sheet by selling them to a special purpose vehicle, which in turn finances the purchase of the portfolio of loans by selling securities in the capital markets. The SPV then owns claims on cash flows that are essentially passive, and consequently the SPV is not an actively managed vehicle. There are a number of other, related, securitization vehicles/methods which are not our focus, but which are very briefly discussed in this subsection. These include loan sales, asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) conduits, structured investment vehicles (SIVs), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). What follows is a partial literature survey about these forms of off-balance sheet activity.

Loan sales refer to the sale of a single commercial and industrial loan, or part of such a loan, by writing a new claim that is linked to the loan, known as a secondary loan participation. Loan sales are significant in size. For example, in 2006, the ratio of on-balance sheet loans (totaling $1,126 billion) to the secondary loan market volume was 21%. See Gorton (2010). Not only are loan sales quantitatively significant, they are important as well simply because they occur. Loan sales are not supposed to happen according to the traditional theories of banking, but following the advent of the junk bond market, banks began to sell loans. Although not required to retain part of the loan, banks in fact do retain pieces, more so for riskier borrowers. Also, loan covenants are tighter for riskier borrowers whose loans are sold. On loan sales, see, e.g. Pennacchi (1988), Gorton and Pennacchi (1995, 1989), and Drucker and Puri (2009). Loan sales are a topic in their own right, and we do not pursue them here.

ABCP conduits and SIVs are limited-purpose operating companies that undertake arbitrage activities by purchasing mostly highly rated medium- and long-term ABS and funding themselves with cheaper, mostly short-term, highly rated commercial paper and medium-term notes. ABCP conduits peaked at just over one trillion dollars outstanding just before the financial crisis. The differences between ABCP conduits and SIVs are described by Moody’s (February 3, 2003), Moody’s (January 25, 2002), and Standard and Poor’s (September 4, 2003). During the crisis many of vehicles were forced to unwind, or they were re-absorbed onto the sponsors’ balance sheets, as investors refused to roll their short-term liabilities. See Covitz, Liang, and Suarez (2009).

There are several important differences between the special purpose vehicles (SPVs) used in securitization and ABCP conduits and SIVs. First, securitization SPVs are not managed; they are robot companies that are not marked-to-market. New portfolios of loans may be sold into these SPVs, but they simply follow a set of prespecified rules. Unlike securitization vehicles, ABCP conduits and SIVs are managed, and though there are strict criteria governing their decisions; portfolio managers make active decisions. Second, they are market-value vehicles. That is, they are required by rating agencies to mark portfolios to market on a frequent basis (daily or weekly), and based on the marks they are allowed to lever more or required to delever. On SIVs, see Moody’s (January 25, 2002), and on ABCPs see Moody’s (February 3, 2003).

CDOs and CLOs are special purpose vehicles that buy portfolios of ABS, in the case of CDOs, and commercial and industrial loans, in the case of CLOs. These are financed by issuing different tranches of risk in the capital market, rated Aaa/AAA, Aa/AA to Ba/BB. These vehicles are also managed, that is, not completely passive. CDOs are described by Duffie and Garleanu (2001) and Benmelech and Dlugosz (2009); also see Longstaff and Rajan (2008). CLOs are discussed by Benmelech, Dlugosz, and Ivashina (2010).

The securitization that is the focus of this survey is quantitatively by far the most important.

3 Overview of the Performance of Asset-Backed Securities

In this section we briefly review the performance of asset-backed securities. First, we look at the growth and size of the market. Second, we examine the default performance and ratings performance of asset-backed securities. Next we examine spreads. Finally, we briefly look at ABS during the recent financial crisis.

3.1 The Size and Growth of the ABS Market

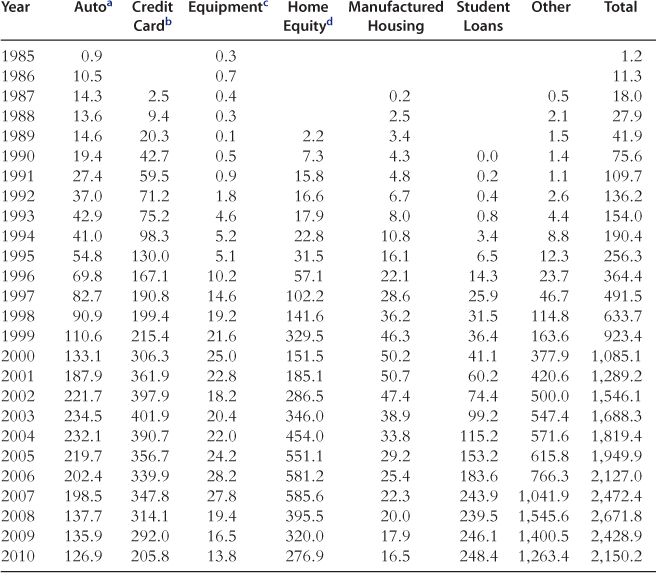

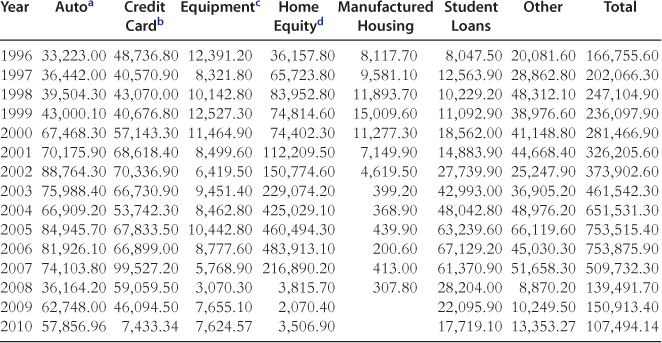

As discussed in the Introduction, securitization was sizeable prior to the recent financial crisis. To briefly review, Figures 1–4 show the issuance amounts annually for US mortgage-related ABS, non-mortgage ABS, and European issuance. Mortgage-backed securities represent a very large asset class. See Table 1. By looking at non-mortgage ABS, and comparing that to US corporate issuance, a better sense of the significance of securitization is portrayed; see Figure 2. Indeed Figure 2 shows that in 2005 issuance of non-mortgage ABS exceeded corporate bond issuance by a small amount. The main categories of non-mortgage ABS include credit card receivables, automobile loans, and student loans. Tables 2 and 3 show the amounts of non-mortgage ABS outstanding amounts and amounts by issuance, respectively.

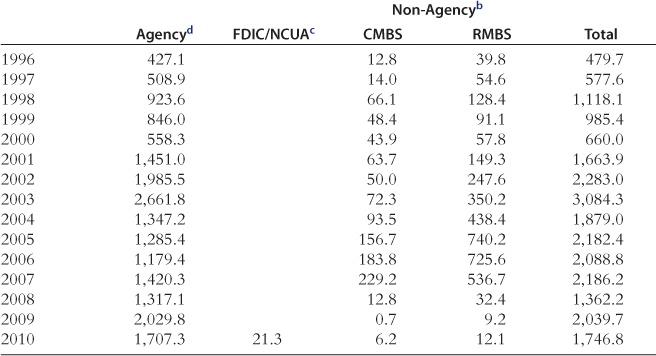

Table 1 US asset-backed securities outstanding ($ billions)

Sources: Bloomberg, Dealogic, Fitch Ratings, Moody’s, prospectus filings, Standard and Poor’s, Thomson Reuters, compiled by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

aAuto includes truck loans and wholesale auto receivables, and as of 2008 includes floorplans, motorcycles, rentals, and recreational vehicles. Prior years have not been revised to include these categories yet.

bCredit Cards include charge cards.

cEquipment does not include aircraft leases.

dHome Equity contains both 1st and junior lien home equity loans and lines of credit, subprime, small balance issues, and servicing rights; these numbers do not overlap with mortgage-related issuance in other SIFMA statistics.

Table 2 US asset-backed securities issuance ($ millions)

Sources: Bloomberg, Dealogic, Fitch Ratings, Moody’s, prospectus filings, Standard and Poor’s, Thomson Reuters, compiled by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

aAuto includes truck loans and wholesale auto receivables, and as of 2008 includes floorplans, motorcycles, rentals, and recreational vehicles. Prior years have not been revised to include these categories yet.

bCredit Cards include charge cards.

cEquipment does not include aircraft leases.

dHome Equity contains both 1st and junior lien home equity loans and lines of credit, subprime, small balance issues, and servicing rights; these numbers do not overlap with mortgage-related issuance in other SIFMA statistics.

Table 3 US mortgage-related securities issuancea (USD billions)

Sources: FDIC, GSEs, Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg, compiled by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

aIncludes GNMA, FNMA, FHLMC mortgage-backed securities, CMOs, private-label MBS/CMOs. Does not include certain subprime categories, which are included in the Home Equity category of ABS.

bNon-agency includes CMBS and RMBS, and may include re-REMICs.

cFDIC transactions are structured transactions backed by assets of failed banks and may include non-mortgage related collateral; NCUA transactions are structured transactions backed by assets of failed credit unions and may include non-mortgage related collateral.

dAgency transactions include both single and multifamily MBS and CMOs.

Securitization is not just a US phenomenon. It is a global phenomenon. The amounts issued in Europe are also significant. Figure 4 shows European issuance of some selected asset classes of ABS. Tables 4 and 5 show European securitization outstanding amounts and amounts by issuance, respectively. Table 6 breaks down European issuance by country. Securitization is also important in Asia and Latin America; see, e.g. Gyntelberg and Remolona (2006) and Scatigna and Tovar (2007)

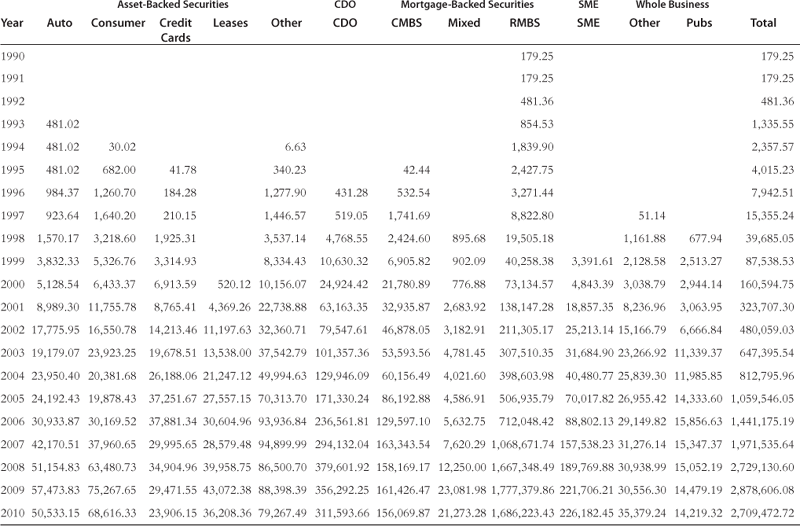

Table 4 European securitization outstanding, USD millions

Sources: AFME & SIFMA Members, Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters, prospectus filings, Fitch Ratings, Moody’s, S&P, AFME & SIFMA, compiled by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association.

Table 5 European securitization issuance, USD millions

Sources: AFME & SIFMA Members, Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters, prospectus filings, Fitch Ratings, Moody’s, S&P, AFME & SIFMA, compiled by the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. 2. WBS: Whole Business Securitization. Certain WBS structures may be bucketed in other categories (ABS and CMBS) based on the nature of the transaction and are evaluated on a case by case basis.

aSME: Small and Medium Enterprises

Table 6 European securitization issuance, USD millions

Sources: AFME & SIFMA Members, Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters, prospectus filings, Fitch Ratings, Moody’s, S&P, AFME & SIFMA.

a“Multinational” contains collateral from multiple and/or unknown countries; most CDOs are bucketed in this group.

b“Other” countries include countries too small to be displayed: Austria, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, the Channel Islands, Hungary, Iceland, Poland, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, and the United States.

c“PanEurope” collateral consists of collateral predominantly sourced from multiple European countries.

.

Further, securitization prior to the financial crisis was growing in the sense that new asset classes were increasingly becoming securitized. Table 7 lists some of the asset categories that have been securitized. The securitization of life insurance assets and liabilities is an important new asset class; see Cummins (2004) and Cowley and Cummins (2005).

Table 7 Major securitized asset classes

| Aircraft leases | Manufactured housing loans |

| Auto loans (prime) | Mortgages (prime) |

| Auto loans (subprime) | Mortgages (alt-A) |

| Auto leases | Mortgages (subprime) |

| Commercial real estate | Mortgages (commercial) |

| Computer leases | RV loans |

| Consumer loans | Small business loans |

| Credit card receivables | Stranded utility costs |

| Equipment leases | Student loans |

| Equipment loans | Trade receivables |

| Franchise loans | Time share loans |

| Future flows receivables | Tax liens |

| Healthcare receivables | Taxi medallion loans |

| Health club receivables | Viatical settlements |

| Home equity loans | Whole businesses |

| Intellectual property cash flows | |

| Insurance receivables | |

| Motorcycle loans | |

| Music royalties |

Source: Rating agency reports.

3.2 The Default and Ratings Performance of ABS

We next present a general overview of the default and ratings performance of asset-backed securities. There are several ways to describe performance. One way is to examine default rates. Another is to look at credit rating changes. Our goal is modest. We want to convey some sense of performance, by these measures. We do not present an analysis of this asset class in a portfolio context. We start by looking at Standard and Poor’s default rates, in Table 8. The table shows cumulative default rates (conditional on survival) as a percentage for all globally issued asset-backed securities, over the period 1978–2010. Also, for comparison purposes are cumulative default rates for US corporate bonds. The table looks at cumulative default rates for one year through ten years. Standard errors are in parentheses. The table shows the following:

• Comparing AAA-rated ABS to AAA-rated corporate bonds, ABS AAA-rated securities have significantly higher cumulative default rates compared to corporates.

• This is also true of all other rating categories, but the differences lessen as ratings worsen.

• The standard errors of the default rates are also higher for ABS.

Table 8 S & P global structured finance cumulative default rates conditional on survival, 1978–2010 (%; standard errors in parentheses)

Source:Standard’s (2011a, 2011b).

Table 9 is similar in that it looks at cumulative impairment rates for ABS, and separates ABS without excluding subprime-related securities, the top panel, from subprime mortgage-backed securities, in the middle panel. In the bottom panel is comparable information for globally issued corporate securities. Impairment is different than default, which is a more certain endpoint for the security. Default is relevant to debt and includes: (1) a missing or delayed contractually obligated interest of principal payment; (2) bankruptcy or receivership; (3) distressed exchange; or (4) change in terms of payment imposed by a sovereign that result in a lower financial obligation. “Impairment” includes those four events and also includes cases where: (1) there has been an interest shortfall or principal write-down or loss that has not been cured; (2) the security has been downgraded to Ca or C; or (3) has been subject to a distressed exchange. Impairment status may change over time if a security cures an impairment event. See Moody’s (2011).

Table 9 Cumulative impairment and default rates

Source:Moody’s (2010a, 2010b).

Table 9 breaks out subprime, revealing some very important differences:

• ABS impairment rates, excluding subprime, are still higher than the default rates for global corporate (non-ABS) securities, but the difference is not as great.

• Impairment rates for subprime mortgage-backed securities are significantly higher than for ABS excluding subprime.

• As in the previous table, default rates for global corporate (non-ABS) securities are lower than for subprime.

Table 10 shows time series 5-year default rates for global ABS over the period 1978–2010, by year and rating. The financial crisis took place during 2007–2008, but the effects on ABS defaults have a lag. These data show that the years of 2009 and 2010 account for the higher default rates. This is the effect of the financial crisis. Below we will look at the financial crisis in terms of spreads.

Table 10 S & P global structured finance 5-year default rates, 1978–2010 (%)

Source:Standard and Poor’s’s (2011a).

3.3 ABS Performance in Terms of Spreads

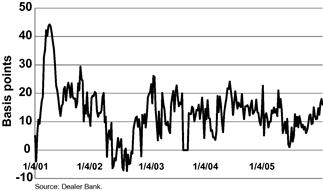

We next examine ABS spreads. As with credit ratings, we use the spreads on AAA corporates, namely, Industrials, as a benchmark. The Industrials are in the form of credit default swaps. We focus on AAA because corporate bonds and asset-backed securities with this rating should be the most comparable. We compare Prime Auto ABS with a 3-year maturity and Credit Card ABS with a 5-year maturity, to AAA Industrials with a maturity in the 3–5 year bucket.

The data are from a dealer bank and represent on-the-run bonds. We focus on the difference in spreads to highlight the difference between AAA Credit Card ABS and Industrial Corporates, conditional on rating. Figure 8 shows the difference in spreads over the period 2001–2005, a relatively normal period. Several points stand out. First, the difference in spreads is typically positive, that is, AAA Credit Card ABS trade higher than AAA Industrial Corporates. Second, looking at the scale on the y-axis, the difference in spreads is typically very low, around 10 basis points. Also, not observable is the observation that the Industrial Corporate spreads are more volatile. No research that we know of has investigated whether these observations are true more generally.

Figure 8 Difference in spreads: AAA credit card ABS minus AAA industrials, 2001–2005.

3.4 Performance During the Financial Crisis

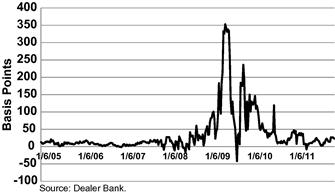

In terms of ratings we saw the effects of the financial crisis above. Figure 9 again looks at the difference in spreads between AAA Credit Cards and Industrial Corporates, as in Figure 8, but now for the period 2005 through March 2011, spanning the financial crisis. The spread on AAA Credit Cards spikes during the crisis, relative to Industrial Corporates. Figure 10 shows the level of the spread for AAA Credit Cards and Industrial Corporates, as well as AAA Prime Auto receivables. During the crisis, all three asset classes moved together, although none are subprime. See Gorton and Metrick (2012).

Figure 9 Difference in spreads: AAA credit card ABS minus AAA industrials, 2005-march 2011.

Figure 10

Figure 11 Spreads: AAA ABS vs. subprime (10 year maturity).

Although SPVs are separate legal entities, during the financial crisis sponsors brought their credit card off-balance sheet vehicles back on balance sheet. For example, in December 2007 Citigroup brought $49 billion of SPV assets that had been securitized back on balance sheet. JP Morgan and Bank of America also did this. See Scholtes and Guerrera (2009). We discuss this later.

In Section 8 we further discuss the financial crisis and related literature.

4 A Simple Model of the Securitization Decision

In this section we discuss the theory concerning the private securitization decision. Gorton and Souleles (2006) present a slightly more complicated version of this model and solve for the equilibrium. The point of the model outline is to provide a framework for discussing the empirical and institutional literature in later sections.

Suppose the riskless interest rate, r, is 0 and that all agents are risk neutral. Borrowers and lenders must then break-even. A competitive bank has two one-period loans, each of $1 principal; each dollar is to be repaid at the end of the period (since r = 0). Suppose each loan defaults with independent probability p. If a loan defaults it repays nothing. The loans are financed with equity (E) and debt (D). The debt (demand deposits) is special in the sense that it is used as a transaction medium, so it has a convenience yield of ρ. We assume that E < $2, so some debt is needed. The debt is one-period and promises to repay F at the end of the period (since r = 0). Debt is tax-advantaged so that effectively only (1-τ)F needs to be repaid, where τ is the relevant tax rate. If the bank defaults then there is a bankruptcy cost, c, borne by the creditors. Further, for simplicity, we assume that 2 > F > 1, i.e. both loans must pay off in order to repay the debt holders without losses.6 In other words, there are effectively two outcomes: both loans pay off, which occurs with probability (1-p)2, in which case creditors are repaid in full; there is a default by the bank, in which case creditors lose c.

In order for investors to be willing to buy the debt of this bank, the repayment amount F must satisfy:

![]() (1)

(1)

where the probability that both loans succeed is (1-p)2, and the other three cases involve the bank failing and the creditors recovering nothing and bearing the bankruptcy cost c.7

From (1), the lowest promised repayment amount that the lenders will accept is:

![]()

The bank’s expected profit is:

![]() (2)

(2)

It is apparent that on-balance sheet debt is more advantageous to the extent that it is tax-advantaged and less desirable to the extent that the bankruptcy cost is higher. Further, if there is a convenience yield on the bank debt, ρ > 0, then that also makes debt desirable.

Equation (2) is a simple representation of the traditional bank business model. The bank borrows in the demand deposit market and lends the money out. As long as ![]() , where E is the initial investment of the equity holders, then this is a successful business model. Moreover, because of limitations on entry and subsidized deposit insurance, it may be that

, where E is the initial investment of the equity holders, then this is a successful business model. Moreover, because of limitations on entry and subsidized deposit insurance, it may be that ![]() . That is, because of limited entry into banking and local monopoly power, the bank may earn monopoly rents, not included in the above model. In the banking literature, such rents are referred to as “charter value” or “franchise value” and potentially play an important role.

. That is, because of limited entry into banking and local monopoly power, the bank may earn monopoly rents, not included in the above model. In the banking literature, such rents are referred to as “charter value” or “franchise value” and potentially play an important role.

Later we will be interested in the question of why securitization developed. One motivation for its development is that this traditional bank business model became less profitable, and charter value declined in the face of competition. For example, if money market mutual funds entered the market to compete with demand deposits, then D would fall to D’ ceteris paribus. If junk bonds entered to compete with loans, then possibly the remaining lending opportunities became riskier, p rising to p’. We review the evidence on this below.

Now, consider the case where one loan is securitized. This means that the bank sells one loan to a special purpose vehicle (SPV), which finances the purchase of the loan by issuing debt in the capital markets. The SPV will borrow DSPV promising to repay FSPV at the end of the period. The bank then has two assets on its balance sheet, an equity claim on the SPV and one loan. Suppose that the bank uses the proceeds of the loan sale to the SPV to pay down on-balance sheet debt.

The SPV has no bankruptcy costs; its debt is not tax-advantaged. The asset-backed security issued by the SPV, DSPV, may also provide a convenience yield to its holder, ρ’.8

With securitization (sec) investors in the on-balance sheet debt require:

![]()

![]() indicates the on-balance sheet debt when the bank has securitized a loan, to be distinguished from D above, the case where there is no securitization. Both of these may involve a convenience yield, but we keep such notation suppressed.

indicates the on-balance sheet debt when the bank has securitized a loan, to be distinguished from D above, the case where there is no securitization. Both of these may involve a convenience yield, but we keep such notation suppressed.

And investors in the off-balance sheet debt require:

![]()

where 0 < ρ < 1 is the convenience yield.

So, ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

With securitization (sec), bank profits now are:

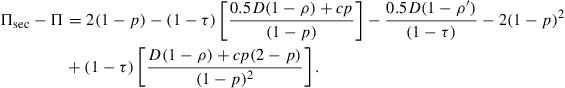

Assume that the on- and off-balance sheet positions are symmetric, i.e. Dsec = Dspv = 0.5D. Then:

(3)

(3)

If (3) is positive, then securitization is profitable, otherwise not. To understand (3), let:

So, ![]() .

.

Note that ![]() . Also,

. Also, ![]() .

.

The four terms identify some possible sources of value to securitization, as compared to financing all assets on-balance sheet. Term A (bankruptcy optionality) is unambiguously positive because the bank now has the option of going bankrupt in pieces. That is, the off-balance sheet loan can default without the bank going bankrupt. Term B (bankruptcy costs) is unambiguously positive because expected bankruptcy costs are lower, since the SPV does not face bankruptcy costs. Term C (taxes) is ambiguous. There is a loss of a valuable tax shield because less debt is issued on-balance sheet. This favors on-balance sheet debt financing, unless expected bankruptcy costs, cp, are too large. Finally, term D (relative convenience yield) is ambiguous. Its sign depends on the relative convenience yields of on- and off-balance sheet debt. On-balance sheet debt refers primarily to demand deposits. If there is no convenience yield to off-balance sheet debt (i.e. ρ’ = 0), then term D is unambiguously negative, that is, it favors on-balance sheet debt. If the debt issued by the SPV has a convenience yield then this term becomes ambiguous.

Term A appears straightforward, but is perhaps not. All firms would like to be composed of parts, say divisions, which can go bankrupt as stand-alone entities, so that equity holders retain control of the remaining divisions. But this is not possible because decisions need to be made about the activities of each division and these decisions are made by the “firm”. Value is added presumably by corporate decisions, overseen by the equity holders. Corporate control over the activities ties control rights to cash flow rights. Thus, the divisions are part of the firm, and it is this entity—the firm—that borrows and faces the possibility of bankruptcy. How can a financial firm divide itself into parts, the on-balance sheet firm and the off-balance sheet SPV? The answer is that the cash flows sold to the SPV are passive; there are no further decisions to be made since the loans have already been granted. What remains is for borrowers to repay the loans (servicing is outsourced) and, if they do not, for repossession to take place (also outsourced). In this sense, the cash flows are passive. Consequently, cash flow rights and control rights can be separated.

The sign of B, the bankruptcy costs, is unambiguous because the SPV cannot become bankrupt. This was an innovation. That is, the design of SPVs to have this feature is an important part of the value of securitization. Moreover, it has economic substance. Since the cash flows are passive, there are no valuable control rights over corporate assets to be contested in a bankruptcy process. Thus, it is in all claimants’ interest to avoid a costly bankruptcy process. Below, we review some of the legal features which make the SPV liquidation-efficient.

The tax advantage of on-balance sheet debt, term C, is straightforward. The tax advantage does not apply to SPV debt because SPVs are tax neutral. If they were not, then the profits from lending would be taxed twice, making securitization infeasible. However, the model does not include taxes on corporate profits. Han, Park, and Pennacchi (2010) point out that the presence of profit taxation favors securitization. On-balance sheet funding requires some equity financing because of regulatory capital requirements or internal risk management. But, such bank equity is costly because it does not have a tax shield like debt does. Consequently, the bank will end up paying taxes on the returns from its equity capital financing. Compare this to securitization. When the bank funds off-balance sheet, the SPV pays no corporate taxes. So, on-balance sheet financing, to the extent that it is equity financed, is disadvantageous to the bank’s shareholders. We discuss Han et al. (2010) empirical tests of this mechanism in Section 7.

Finally, there is the issue of the relative convenience yield. Demand deposits are used as a transaction medium, and consequently may earn a convenience yield. Since there are now competitors to demand deposits, in particular, money market mutual funds, this convenience yield may have eroded in the last thirty years. We discuss the literature on this below. Also, as we discuss below, there may also be a convenience yield that derives from the debt issued by SPVs, since this debt was used as collateral for sale and repurchase agreements prior to the crisis. Even if not used as collateral, there may be a demand for AAA-rated assets if they are easier to sell (if need be) without incurring losses (to better informed agents).

5 The Origins of Securitization

Securitization is a fairly recent development, having started roughly thirty-five to forty years ago.9 Why did it start? In this section we outline some of the hypotheses about the origins of securitization, and tie these hypotheses and some evidence to the components of the model from Section 4. We first discuss the literature related to the possible changes that caused financial intermediaries to move increasingly to off-balance sheet financing. Then we briefly outline possible explanations for where the demand for asset-backed securities came from, that is, who are the investors? And, what are the uses of asset-backed securities? Here, there is even less literature and so we are necessarily speculative. Thirdly, we ask whether there was financial innovation specific to securitization that reduced its cost and assisted its introduction and growth.

5.1 The Supply of Securitized Bonds

Why did banks switch from on-balance sheet financing to off-balance sheet financing? Above, we have outlined the factors affecting this decision. In this subsection we ask what changed to alter this calculation. Banking scholars have documented important changes in US banking starting in the early 1980s that caused the traditional banking model to become less profitable.10 Securitization appears at the same time, suggesting that it was a response to this decline in profitability. In the context of the model, these changes can take many forms, or it could just be that increased competition forces managers closer to the profit-maximizing ideal of our model, and less likely to rely on monopoly rents to lead a quiet life. We briefly review these factors below, although no one has explicitly linked these changes to the origins of securitization.

Basically, the argument is that commercial banks were protected from competition in various ways following the legislation passed during the Great Depression, allowing them to earn monopoly profits. But, this position starts to erode in the 1980s due to competition and innovation. Coming out of the Great Depression, banks had unique products, bank loans, and demand deposits. Demand deposits were insured and access to corporate debt markets was limited to large firms. Entry into banking was limited for two reasons. First, entry was limited because until 1994 branching across state lines was prohibited.11 Second, entry into banking was restrictive because banks had to obtain a charter from either the federal or state government. Peltzman (1965), in a famous paper, concluded that competition for chartering banks was reduced by the passage of the Banking Act of 1935. He found that the federal control of chartering had reduced the rate of bank entry by at least 50%, based on a comparison of the rate of entry before 1936 to the rate during the period 1936–1962. Due to limited entry, banks had local monopolies on demand deposits, e.g. see Neumark and Sharpe (1992), and Hannan and Berger (1991). There were also more direct subsidies to banks in the form of interest rate ceilings on deposit accounts (Regulation Q, which had its origin in the original deposit insurance legislation), until lifted by the Monetary Control Act of 1980.12 On the asset side of bank balance sheets, bank loans were the main source of external funding for nonfinancial firms. In particular, prior to the 1980s firms with no presence in the capital markets relied on banks for funding. In short, having a bank charter was valuable. In the banking literature this became known as “charter value”.

The traditional and comfortable model of banking changed dramatically during the 1980s and 1990s. These changes have been much noted and much studied, so we only briefly review them here. Berger et al. (1995), who exhaustively document the changes, put it this way in 1995: “Virtually all aspects of the US banking industry have changed dramatically over the last fifteen years” (p. 55). They go on to describe the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s as “undoubtedly the most turbulent period in US banking history since the Great Depression” (p. 57). Limited entry protection disappears during the 1980s. Keeley (1985) argued that: “The recent deregulation of banking, in particular the removal of deposit-rate ceilings on almost all types of consumer accounts, appears to be taking place in an environment in which entry restrictions have been effectively eliminated or at least have been substantially relaxed.” A large literature documents the decline in bank charter value; see, e.g. Keeley (1990).

Two particular changes are worth briefly noting, one on each side of the bank balance sheet. On the asset side, substitutes for bank loans arose and took market share away from banks. In the 1980s there was a dramatic shift in corporate finance: junk bonds and commercial paper became substitutes for bank longer-term and shorter-term loans, respectively, and represent an important step in the unbundling of the traditional intermediation process. Junk bonds (high yield bonds or below investment-grade bonds) substituted for bank loans. Instead of regulated commercial banks, other firms, notably Drexel Burnham Lambert, specialized in underwriting debt for below investment-grade companies. Taggart (1988a, 1988b) documents this change, observing that bank loans accounted for 36.6% of the total credit market debt raised during the period 1977–1983, but only 18.2% of the total debt raised between 1984 and 1989. Borrowing via public debt markets increased from 30.5% to 54.2% over this period. The junk bond market grew from $10 billion in the early 1980s to over $200 billion by the end of the decade (see Taggart (1990)). This growth came at the expense of bank loans. Benveniste, Singh, and Wilhelm (1993) provide evidence that junk bonds and bank loans are substitutes. They examine the abnormal returns to money center banks associated with the SEC’s actions against Drexel and find statistically and economically excess returns associated with these events. In other words, bad news for Drexel was good news for large commercial banks; and good news for Drexel was bad news for the money center banks. Small banks’ stocks were not affected, but other investment banks benefited when there was bad news for Drexel, and vice versa.

The competitor for short-term bank loans is commercial paper (CP), a short-term debt contract issued directly by firms into the capital markets. The growth in this market is described by Post (1992). Over the 1980s, the CP market (outstanding) grew at a 17% average annual compound growth rate (see Post (1992)). Also see Hurley (1977). CP has many of the attributes of short-term, unsecured, bank loans, but it is not a good substitute for loans for all firms because only the largest most credit-worthy firms can issue CP.

Commercial banks also came under attack on the liability side of the balance sheet; see Keeley and Zimmerman (1984), Keeley and Zimmerman (1985). Another very marked transformation to the financial system was the shift in the source of transaction media away from demand deposits toward money market mutual funds (MMMFs).13MMMFs were a response to interest rate ceilings on demand deposits (Regulation Q). In the late 1970s MMMFs were around $4 billion. In 1977, interest rates rose sharply and MMMFs grew in response, growing by $2 billion per month during the first five months of 1979 (see Cook and Duffield (1979)). The Garn-St. Germain Act of 1982, however, authorized banks to issue short-term deposit accounts with some transaction features, but with no interest rate ceiling. These were known as “money market deposit accounts”. In the three months after their introduction in December 1982 these accounts attracted $300 billion. Keeley and Zimmerman (1985) argue that the response of banks resulted in a substitution of wholesale for retail deposits, and direct price competition for nonprice competition, both responses resulting in increased bank deposit costs.

Competition and deregulation lowered bank profits starting in the early 1980s. The traditional model of banking broke down. This is the environment in which securitization arose. If banks found that off-balance sheet financing was cheaper than on-balance sheet financing, given that the cost of bank capital rose, for example, due to deposit rate ceilings being lifted, among other things, then there was an incentive to securitize. This, however, remains an important topic for future research.

5.2 Relative Convenience Yield and the Demand for Securitized Bonds

If banks had an incentive to supply asset-backed securities starting in the 1980s, where did the demand for these securities come from? Institutional investors no doubt provided one source of the demand. The amount of money under the management of institutional investors also grew exponentially during this period. Pozsar (2011) surveys the rise in demand for securitized bonds from institutional investors. The demand for securitized bonds may also be linked to a significant extent to the growth in the demand for collateral. In different parts of financial markets participants need to post collateral. The collateral must be high-grade bonds. If the demand for collateral exceeds the available stock of US Treasury bonds and agency bonds, then asset-backed securities would be needed as collateral. In the language of our model, the increased demand for safe collateral would be an increase in the convenience yield of securitized bonds (ρ’) and a decrease in the relative convenience yield of bank deposits (ρ). This appears to have been the case, though the evidence is very indirect.

Demands for collateral come primarily from three areas. First, in the last thirty years derivative products, e.g. interest rate swaps and swaptions, foreign exchange swaps, have grown from nothing to many trillions of dollars of notional. Derivatives require posting collateral when the position becomes a liability for one side of the transaction. Second, clearing and settlement requires the posting of collateral. Ironically, securitization increases the volumes in clearing and settlement as it creates securities out of previously non-tradeable loans. Third, with the rise of institutional investors and more sophisticated corporate treasury departments, the use of sale and repurchase agreements (repo) appears to have increased dramatically. Repo requires the use of collateral. Added to these increases in demands is the fact that a very large fraction of US fixed income securities are held abroad and not available for use as collateral. Prior to the government response to the financial crisis, it seems that there was an insufficient amount of US Treasuries available for use as collateral, and ABS have many design features that make them a useful substitute.

Securitization has important features that make it very attractive as collateral. A desirable feature of collateral is that it is information-insensitive (see Gorton and Pennacchi (1990), and Dang, Gorton, and Holmström (2011)), so it preserves value. “Information-insensitive” refers to the property of debt that it is not (very) profitable for an agent to produce private information about the payoffs of the security. Such securities can be traded without fear of adverse selection. ABS are debt claims, and so are senior securities. Further, asset-backed securities have some unique features that make them particularly valuable as collateral. First, the SPV organized as a trust has no equity that is traded, so no one has an incentive to produce information about this residual claim, and so as a by-product there is no information produced that would have an impact on the ABS. Second, there is no managerial discretion that can dramatically alter the risk profile of the underlying assets. Since the assets are passive cash flows, emanating from many contractual arrangements, the assets of the SPV are expected to retain their value. In other words, the payoffs are more certain, since they are not affected by managerial discretion. Schwarcz (2003, p. 561): “The essential difference between [commercial trusts and corporations] turns on the degree to which assets need to be at risk in order to satisfy the expectations of residual claimants. In a corporation, the residual claims are sold to third-party investors (shareholders) who expect management to use corporate assets to obtain a profitable return on their investments. But that creates a risk that the corporation will become insolvent … In contrast, a commercial trust’s residual claimant is typically the settler of the trust, who … does not expect a risk-weighted return. The expectations of the trust’s senior and residual claimants are therefore the same: to preserve the value of the trust’s assets.”

With respect to the use of collateral for derivatives positions, there are surveys conducted by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). According to ISDA (2009), “the amount of collateral used in connection with over-the-counter derivatives transactions grew from $2.1 to $4.0 trillion during 2008, a growth rate of 86%, following 60% growth in 2007” (p. 2). Growth in collateral for derivatives grew not only because the use of derivatives grew, but also because the use of collateral to mitigate counterparty risk in derivatives grew, and the use of two-way collateral agreements has grown.14 Also, see Bank for International Settlements (BIS) (2007).

With regard to clearing and settlement, real-time gross settlement systems (RTGS) have been widely adopted in the last twenty years (see, e.g. BIS (1997)).15 Problems can arise in a RTGS system when one bank does not have enough funds in its central bank account, in which case the transaction can be rejected or the central bank can extend intraday credit. The possibility that credit may be extended to a bank raises the question of collateral requirements. Many central banks provide intraday credit through fully collateralized intraday overdrafts or intraday repos. In general, the amount of collateral required varies across different RTGS systems and across the parties involved. There are no data available to determine how much collateral is used for clearing and settlement.

The final source of demand for collateral is the repo market. In a sale and repurchase agreement (or repo) one party (the lender) deposits cash with another party, the borrower. The transaction is short-term, usually overnight, and the depositor receives interest on their deposit. To ensure the safety of the deposit, the depositor receives collateral, which he takes physical possession of. The issue is: What is this collateral?

The repo market appears to have grown enormously over the last 30 years, but there is limited data with which to measure this growth. According to Federal data, primary dealers reported financing $4.5 trillion in fixed income securities with repo as of March 4, 2008. But, this covers only a fraction of the repo market in the US.16 The US Bond Market Association (now known as the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association) conducted a survey of repo and securities lending in 2005, estimating that the total exceeded $5.21 trillion. Estimates of the size of the repo market in total lead roughly to a market that is about $10 trillion. See Gorton and Metrick (2012), Singh and Aitken (2009), and Hördahl and King (2008) for different approaches to estimating the size of this market. While the available evidence is very suggestive that the repo market is very large, it is impossible to say exactly how large.

As mentioned, these three sources of demand for collateral may have outstripped the available collateral in the form of agency and Treasury bonds. In fact, of all the available collateral consisting of US Treasuries, agency bonds, corporate bonds, and asset-backed securities, a large fraction is held abroad, which may not then be available to use as collateral. Foreign holdings of US securities have grown significantly in recent years. In June 2007, foreigners held 57% of US Treasuries, 21% of US government agency debt, and 23% of US corporate and asset-backed securities. See US Treasury (2010). It is not known how much of this is unavailable for use as collateral.

There is no direct evidence that these demands for collateral led to increased asset-backed security supply. With a lack of relevant data, the evidence that there is a shortage of collateral is indirect. For example, the Bond Market Association Research (February 1998, p. 2) writes:

… repo activity involving financial assets other than US government obligations are increasing due to dealers’ and investors’ desire to achieve the least expensive and most efficient funding sources for their inventories. In recent years market participants have turned to money market instruments, mortgage and asset-backed securities, corporate bonds and foreign sovereign bonds as collateral for repo agreements. Many market participants expect the lending of equity securities to become a growing segment of the repo market, in light of recent legislative and regulatory changes.

And the Bank for International Settlements (2001):

The use of collateral has become one of the most important and widespread risk mitigation techniques in wholesale financial markets. Financial institutions extensively employ collateral in lending, in securities trading and derivatives markets and in payment and settlement systems. Central banks generally require collateral in their credit operations.

Over the last decade, the use of collateral in wholesale financial markets has grown rapidly. The collateral most commonly used and apparently preferred by market participants are instruments with inherently low credit and liquidity risks, namely government securities and cash. With the growth of collateral use being so rapid, concern has been expressed that it could outstrip the growth of the effective supply of these preferred assets. Scarcity of collateral could increase the cost of financial transactions, slow or inhibit financial activity and potentially encourage greater reliance on more inefficient non-price rationing mechanisms, such as restricting access to markets. (p. 2)

The demands for collateral may have led to demands for asset-backed securities, raising their issue prices and thus making them more attractive to issue. This too is a subject for future research.

5.3 Securitization and Financial Innovation

Since the use of ABS as collateral rests on its contractual features, the growth of securitization may be related to financial innovation in the structure and design of the special purpose vehicle. Securitization requires that some legal entity buy the pool of loans sold by the originator. One important issue concerns the legal form of this entity, the special purpose vehicle or special purpose entity. The first question to be broached in this subsection concerns the choice of legal entity for the SPV, and further, whether there was some innovation with regard to the legal entity that facilitated the growth of securitization. The second question concerns “bankruptcy remoteness”. This is the issue of the separation of the assets sold to the SPV from the originator, in the legal sense that if the originator enters bankruptcy, the assets sold cannot be clawed back. Finally, there is the issue of the structure of the SPV so that it cannot enter bankruptcy.

The SPV cannot be an incorporated firm because incorporation faces double taxation, at the corporate level when the income is earned and then again at the shareholder level when the firm pays dividends to distribute the income. (Although Subchapter S allows this to be avoided, it has some drawbacks.) There are alternatives. Many new legal forms for business organizations are relatively recent arrivals. In the last thirty years limited liability companies, limited liability partnerships, and statutory business trusts have all come into existence. See Hansmann, Kraakman, and Squire (2005). These legal forms are alternative legal structures for housing businesses.

In the example considered above, the Chase Issuance Trust, the SPV was a Delaware Trust, a statutory business trust. The business trust appears to be the basic legal form of the SPV used in securitization. Trusts are also the dominant form of organization for structuring mutual funds and pensions.17 There is little research on why this is so. In fact, Schwarcz (2003, p. 560) notes that: “There are not even clear answers to the fundamental question of whether trusts are a better form of business organization than corporations or partnerships.” Innovation, if it did occur, is related to the use of the business trust and its subsequent evolution into a statutory trust, as explained below.

Trusts are very old, and most commonly were donative trusts, that is, they were used to holds gifts of property, for a beneficiary. Historically, the property was land and buildings. However, the legal form of the trust has been adapted to a more modern use. As Langbein (2007) puts it: “What is new is that the characteristic trust asset has ceased to be ancestral land and has become instead a portfolio of marketable securities … modern trust property typically consists of these complex financial assets…” (p. 1072). This evolution of the type of property held by trusts, also described by Langbein (1995), required legislation to adapt the trust form for this new purpose. For example, trustees need expanded powers and more discretion. Sitkoff (2011) discusses fiduciary obligations in trust law. The Uniform Trusts Act of 1937 and the Uniform Act for Simplification of Fiduciary Security Transfers of 1958 were two such pieces of legislation (see Langbein (2007)). For securitization, another issue was prominent.

There was legal uncertainty about the legality of the trust form and about the limited liability of trusts. Some states explicitly rejected trusts as a legal form, viewing them is incompatible with corporate regulatory rules. There was no statutory recognition of limited liability. Consequently, the promulgation of the Delaware Business Trust Act (1988) was important; it eliminated this uncertainty. The motivation for this act, according to Sitkoff (2005, p. 36) was to provide a viable alternative legal form for business organizations. This act removed the uncertainty about limited liability (see Hannsmann and Mattei (1998), p. 474, note 8), and contained no restrictions on the form of business (see Ribstein (1992, p. 423)). Sitkoff (2005, p. 32), under this act: “The statutory business trust is not only exceedingly flexible, but more importantly it resolves the problems of limited liability and spotty judicial recognition that have cast a pall over the use of the common-law business trust.”

It is also important that Delaware took this step, as this state dominates corporate law. As Levmore (2005, p. 205) put it: “… Delaware is significant, and perhaps as important, in partnerships and limited liability companies as it is for corporations. Whatever the source of its dominance in corporate law, that … carries over to uncorporate law.” Various states adopted general business trust statutes following Delaware (though a few states predate it).

Delaware’s laws, and similar laws adopted by other states, can suffer from the fact that not all states recognize these laws. The Uniform Law Commission, adopted in 1892, centralizes the drafting of laws so that all states can adopt the same set of rules. The commission has commissioners appointed by the governors of all the states. This commission has, historically, played an important role in transforming traditional donative trust law into statute (see Langbein (2007)). In 2003, a drafting committee for a Uniform Business Trust Act was set up by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Law. Sitkoff (2005, p. 6): “The Uniform Statutory Trust Entity Act, now in draft form, validates the statutory trust as a permissible form of business organization.” In 2009 the Uniform Statutory Trust Entity Act was passed, and is currently being revised. See Rutledge and Habbart (2010) for a summary.

The Delaware act was important for modifying and clarifying a number of troublesome features of the traditional trust. But the issue of bankruptcy remoteness was still troubling. One of the most important issues in securitization concerns the status of the claims of the SPV investors in the event that the originator of the SPV’s assets goes bankrupt. See Hunt, Stanton, and Wallace (2011) for an overview of the history of bankruptcy remoteness. That is, the issue is whether there was a “true sale”, so that the creditors of the originator cannot claim to be entitled to the securitized assets. This issue first arose in the bankruptcy case of LTV Steel Company, in which LTV challenged its own securitizations, claiming that they were not true sales.

The LTV Steel case (In re LTV Steel, Inc., No. 00-43866, 2001 Bankr. LEXIS 131 (Bankr. N.D. Ohio Feb. 5, 2001)) threatened the bankruptcy remoteness concept, but the parties settled prior to a court decision and agreed that there had been a “true sale” of the assets to the SPV. 18 Although the outcome was ambiguous, it did not seem to hamper the growth of securitization. In part, that may have been due to another change, the Bankruptcy Reform Act (2001), which provided a safe harbor for ABS. According to Schwarcz (2002, p. 353-54), writing before the act was passed: “… the Reform Act would create, for the first time, a legislative “safe harbor” regarding what constitutes a bankruptcy true sale in securitization transactions.” Under the Act, there is an explicit exclusion from the estate of the bankruptcy entity of an “eligible asset” transferred to an “eligible entity” related to an “asset-backed securitization.” The Act also more broadly defines “transferred” with regard to the sale of the assets to the SPV.

The safe harbor part of the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 2001 was still viewed as being uncertain. So, the State of Delaware enacted the Asset-Backed Securities Facilitation Act (“the Securitization Act”) in January 2002. This Act also addressed the issue of what constitutes a “true sale” for the purpose of bankruptcy, attempting to strengthen it further. Why was this needed? Carbino and Schorling (2003): “The entire federal interest issue might be moot, however, because an argument exists that the plain language of Bankruptcy Code section 541 expressly preempts the Securitization Act.” But, “Our review of federal interests that have been implicated in bankruptcy cases did not reveal a federal interest that expressly trumps the Securitization Act’s purpose to ensure that receivables transferred to an SPV are not recaptured as ‘property of the estate’ in the originator’s bankruptcy.” The authors conclude that “ … the efficacy of the Securitization Act remains uncertain. While the Securitization Act may provide some additional level of comfort to investors when Delaware law applies, it is by no means a panacea.”

President Bush signed “The Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005” on Wednesday, April 20, 2005, making it law. The legislation does not appear to have created a safe harbor for securitizations. Section 541(b)(8) states “any eligible asset (or proceeds thereof), to the extent that such eligible asset was transferred by the debtor, before the date of commencement of the case, to an eligible entity in connection with an asset-backed securitization, except to the extent such asset (or proceeds or value thereof) may be recovered by the trustee under section 550 by virtue of avoidance under section 548(a).”

On April 16, 2009, General Growth Properties, Inc. (GGP), a publicly traded real estate investment trust, filed for bankruptcy under Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code and included in its filing more of its solvent SPVs that owned property and acted as borrowers under the property-specific loans, which were performing in most cases. The case came as a shock to participants in the securitization market. The issue essentially was whether the SPVs’ assets would be substantively consolidated with GGP.

On August 11, 2009 the bankruptcy court delivered a fifty-page opinion that denied the motions to dismiss the case brought by several property-level lenders. See Memorandum of Opinion and Inc. (2009). The court found that the issues should be evaluated based on the group (the company together with the SPVs), but did not substantively consolidate the entities. The opinion is colored by the financial crisis. The court says, “Faced with the unprecedented collapse of the real estate markets, and serious uncertainty as to when or if they would be able to refinance the project-level debt, the Debtors’ management had to reorganize the Group’s capital structure. [Secured lenders] do not explain how the billions of dollars of unsecured debt at the parent levels could be restructured responsibly if the cash flow of the parent companies continued to be based on the earnings of subsidiaries that had debt coming due in a period of years without any known means of providing for repayment or refinance” (p. 30). GGP exited bankruptcy in November 2010. It is not clear what the future impact will be.

Another issue related to the above discussion concerns the case when the originator is an FDIC-insured institution. In 2000, the FDIC adopted a rule that when it acted as conservator or receiver it would not use its statutory authority “to disaffirm or repudiate contracts to reclaim, recover, or recharacterize as property of the institution or the receivership any financial assets transferred by an [insured depository] institution in connection with a securitization” (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) (2010, p. 2). During the financial crisis there was some uncertainty about how the FDIC would behave with respect to securitizations. But the FDIC ended up continuing the safe harbor for financial assets in securitizations.