Chapter 4

Executive Compensation: Where We Are, and How We Got There

Abstract

Keywords

Executive compensationCEO pay; Regulation; Disclosure; Stock options; Accounting; Corporate governance; Sarbanes-Oxley; Dodd–Frank; International Pay

JEL classification

G34; G38; J31; J33; J38; K22; K34; M12; M41; M48; M52

1 Introduction

The first decade of the new century brought significant changes to executive compensation in large US companies. Rocked by scandals ranging from accounting fraud to option backdating—coupled with suspicions that Wall Street bonuses led to excessive risk taking that triggered the financial crisis—compensation committees faced a plethora of new pay-related laws and tax, accounting, and disclosure rules designed to stem perceived abuses in executive pay. After more than tripling (after inflation) during the 1990s stock-option explosion, the median total pay for chief executive officers (CEOs) in the S&P 500 remained relatively stagnant in the early 2000s, and indeed even declined during the 2008–2009 Great Recession. But the flattening of pay levels belied significant structural changes in the composition of pay, as companies adapted to the new regulations and jettisoned stock options in favor of restricted stock. Moreover, realized pay for top-level executives was postured for a new explosion in the second decade of the 2000s, as stock and options granted near the bottom of the market in 2009 became vested and exercisable. These trends suggest the outrage over executive pay—recently reflected by the “Occupy Wall Street” movements and in calls from the Obama administration for increased tax rates for “millionaires and billionaires”—will likely continue unabated over the next several years.

The recent controversies over executive pay are not the first—nor will they be the last—time that executive compensation has sparked outrage and calls for regulation and reform. Indeed, scrutinizing, criticizing, and regulating high levels of executive pay has been an American pastime for nearly a century. In 1932, for example, controversies surrounding high salaries for executives in bailed-out railroads led to pay disclosures and pay caps; disclosure requirements were soon extended to banks, utilities, and large corporations, and further extended to all publicly traded companies following the 1933 and 1934 Securities Acts. Outrage over perceived excesses in “restricted stock option plans” in the 1960s led Congress to prohibit repricing, reduce maximum expiration terms, restrict exercise prices, and extend required holding periods after exercises. In the 1980s, Congress imposed large tax penalties on firms paying (and executives receiving) large severance payments following a change in control, and in the 1990s non-performance-based pay exceeding $1 million was deemed unreasonable and therefore not deductible as an ordinary business expense for corporate income tax purposes. Therefore, the recent backlash over executive pay associated with the accounting and backdating scandals and the financial crisis—triggering Sarbanes-Oxley, new disclosure and accounting rules, restrictions on deferred compensation, and myriad pay regulations under the Dodd–Frank Act—continues a tradition of regulatory responses to perceived excesses and abuses in top-level pay.

The purpose of this study is to document the current state of executive compensation and to show how the level and structure of CEO pay over the past century has evolved in response to economic, institutional, and political factors. My intention is not to provide a comprehensive survey of the academic literature on executive compensation (or even a systematic update of Murphy (1999)), but rather to document a body of facts to guide future theoretical and empirical research in the area. I show that government intervention into executive compensation—largely ignored by researchers—has been both a response to and a major driver of time trends in CEO pay. There have been two broad patterns for government intervention into CEO pay. The first pattern is aptly described as knee-jerk reactions to isolated perceived abuses in pay, leading to disproportionate “one-size-fits-all” responses and a host of unintended and undesirable consequences. The second pattern—best described as “populist” or “class warfare”—arises in situations where CEOs (and other top executives) are perceived to be getting richer when lower-level workers are suffering. Beyond these two broad patterns, indirect intervention in the form of accounting rules, securities laws, broad tax policies, and listing requirements have also had direct impact on the level and composition of CEO pay. In most cases, companies and their executives have responded to the interventions by circumventing or adapting to the reforms, usually in ways that increased pay levels and produced other unintended (and typically unproductive) consequences.

More broadly, this study provides institutional context useful in “explaining” time trends in the level and structure of CEO pay. As emphasized by Frydman and Jenter (2010) and explored below in Section 5, the academic literature focused on explaining these trends is roughly divided into two camps: the “efficient contracting” camp and the “managerial power” camp. The efficient-contracting camp—rooted in optimal contracting theory—maintains that the observed level and composition of compensation reflects a competitive equilibrium in the market for managerial talent, and that incentives are structured to optimize firm value. The managerial-power camp—exemplified in a series of papers by David Yermack, Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried—maintains that both the level and composition of pay are determined not by competitive market forces but rather by captive board members catering to rent-seeking, entrenched CEOs. Frydman and Jenter (2010) conclude that neither camp offers convincing explanations for cross-sectional and time-series patterns in the data.

The efficient-contracting and managerial power camps are not mutually exclusive. For example, in a series of papers designed to explain the escalation in option grants in the 1990s, I have argued that stock options were granted in such large quantities to so many employees in the 1990s because boards and executives (erroneously) perceived options to be essentially free to grant.1 This explanation might be viewed as a combination of both camps: directors yielded to shareholder pressure to tie more closely to equity values, but were duped by managers into the idea that options were free to grant, thus leading to massive grants without any noticeable reductions in other forms of pay. However, as will become clear in Section 3.7 below, a more complete explanation must include the role of government: the option explosion in large part caused by changes to tax and accounting rules coupled with changes in disclosure, holding, and listing requirements.

In essence, the efficient-contracting camp views executive pay as mitigating agency problems between executives and shareholders, while the managerial-power camp views excessive pay as symptomatic of agency problems between shareholders and board members (who often own only a trivial fraction of their firm’s common stock and who are in no sense perfect agents for the shareholders who elected them). The reason government intervention into executive pay adds an important new dimension to the analysis is because the interests of the government differ significantly from those of shareholders, directors, or executives. In particular, as will become evident from the legislative history in Section 3 below, Congressional (and, more generally, public) outrage over executive pay is almost always triggered by perceived excesses in the level of compensation without regard to incentives and company performance, and the regulatory responses have also fixated on pay levels (albeit with little effect).

Limitations on the form of government intervention add another interesting dimension to the agency problem. In most circumstances, Congress has stopped short of directly capping the level of pay or imposing restrictions on its structure.2 However, Congress controls the tax code (including individual and corporate tax rates, punitive excise taxes, and defining what compensation is “reasonable” and therefore deductible by the company), and has routinely used tax rules to regulate pay. In addition, Congress (through its influence on the SEC) indirectly controls disclosure requirements, long the favorite (and singularly most ineffective) tool used to control perceived abuses in pay. Ultimately, attempts to regulate the level of pay through tax and disclosure rules (instead of direct pay caps) have allowed plenty of scope for circumvention and opportunism and other unintended consequences, often leading to the next round of scandals and government responses.

Section 2 (“Where We Are”) analyzes the level and structure of CEO pay packages, discusses measurement issues, explores 1970–2011 time trends and, more generally, serves as a primer on executive compensation. I distinguish between three different measures of total compensation: (1) grant-date pay (based on grant-date values for stock and options, and target values for bonuses); (2) realized pay (based on the vesting of stock awards and the gains from exercising options); and (3) risk-adjusted pay (expected pay from the perspective of risk-averse CEOs). I document the dramatic increase in CEO pay during the 1990s, driven primarily by an unparalleled escalation of stock option grants, and the flattening of pay during the early 2000s (as firms replaced option grants with stock awards). In addition, I provide 1992–2011 time-series evidence on the relation between CEO wealth and shareholder wealth and stock-price volatilities, and discuss incentive issues related to bonus plans and earnings announcements.

Section 3 (“How We Got There”) provides a history of CEO pay in the United States, emphasizing the causes and consequences of government interventions, which have substantially prohibited what would otherwise be highly desirable and productive pay practices. I begin by examining the controversies leading to the first public disclosures of executive pay in the 1930s, which in turn laid the groundwork for all future controversies of, and interventions into, US CEO pay. I document the rise and fall of restricted stock options in the 1950s, created and ultimately destroyed by changes in tax rules. I discuss how wage-and-price controls and a stagnant stock market facilitated an explosion in perquisites in the 1970s; the surrounding controversy led to new tax and disclosure rules (but did not seem to lead to a reduction in perquisites). I show how penalties on golden parachutes in the 1980s appear to have increased the prevalence of change-in control plans; tax gross-ups, early exercise of stock options, and employment agreements. While the increase in option grants in the 1990s in part reflected increased pressure from shareholders to tie CEO pay more closely to performance, I show that the option explosion is largely attributed to tax, accounting and disclosure rules coupled with changes in holding and listing requirements that favored stock options over other forms of incentive compensation. Next, I speculate that the increased reliance on options helped fuel the accounting and backdating scandals in the early 2000s, which in turn led to a variety of government responses and subsequent changes in compensation (including the move towards restricted stock). I then discuss the pay restrictions for recipients of government bailouts during the financial crisis. Finally, I discuss the ongoing implementation of the Dodd–Frank Act.

Section 4 provides international comparisons of CEO pay, based largely on my joint work with Nuno Fernandes, Miguel A. Ferreira, and Pedro Matos (Fernandes et al., 2012). Based on recently available data from 14 countries with mandatory pay disclosures—we show that the stylized fact that US CEOs earn substantially more than foreign CEOs is wrong, or at least outdated. In particular, the “US Pay Premium” became statistically insignificant by 2007 and largely reflects a risk premium for stock-option compensation (which remains more prevalent in the United States than in other countries). In reaching this conclusion, we control not only for the “usual” firm-specific characteristics (e.g. industry, firm size, volatility, and performance) but also for governance characteristics that systematically differ across countries. The remaining differences in pay are largely explained by evolutionary differences in the politics of pay. In particular, Section 3 showed that CEO pay reflects, in part, political responses to perceived (or actual) abuses in pay. Since those perceived abuses differ across countries, the evolution of pay has also differed. For example, CEO pay became highly controversial in both the United States and the United Kingdom in the early 1990s. In the United States, the (likely unintended) result of the controversy was the explosion in stock option grants. In the United Kingdom, the result of a slightly different controversy was to essentially move away from options in favor of performance shares and other forms of equity-based compensation.

Section 5 uses the results in the prior sections to suggest a general theory of executive compensation. I argue that viewing efficient contracting and managerial power as competing hypotheses to “explain” executive compensation has not been productive, since the hypotheses are not mutually exclusive and because they ignore critical political factors and other influences on pay. Ultimately, what makes CEO pay interesting, complicated, and worthy of continued investigation is that the paradigms co-exist and interact.

2 Where We are: A Primer on Executive Compensation

2.1 Measuring Executive Pay

Underlying every intra-firm, cross-sectional, cross-country, or time-series analysis of executive compensation is an assumption (too often implicit) about how to measure the total compensation received by the executives. If executives were simply paid a base salary set at the beginning of each year, it would be easy to compare salaries across executives (within a firm or across firms, industries, and countries) to identify the highest paid, to compare salaries across years to determine how pay has changed over time, and to compare executive salaries to wages paid in other occupations. But consider the following:

• Executives receive compensation in a dizzying array of forms, including base salaries, annual bonuses, long-term incentives, restricted stock, performance shares (i.e., restricted stock with performance-based vesting), stock options, retirement benefits, and perquisites ranging from health benefits to club memberships and personal use of the corporate jet.

• Many of these forms of compensation depend on performance measured over a single or multiple years, and it is not obvious how (or when) to measure them. For example, stock options (which give the executive the right, but not the obligation, to buy a share of stock at a predetermined price) typically have terms of up to ten years. Should stock options be “counted” as compensation when granted, or only when exercised?

• In addition, executives routinely receive lump-sum amounts at various points in time, such as signing bonuses when joining their firms, severance payments upon termination, and change-of-control payments when their companies are taken over. Moreover, some payments “earned” while employed (such as defined-benefit pension obligations) are not paid until long after the executive is retired and his compensation is no longer reported (or sometimes paid as a lump-sum upon retirement). Again, it is not obvious how, or when, to measure these aspects of compensation.

• Finally, different components of compensation impose different amounts of risk on executives. The payoffs from stock options, for example, are inherently more risky than are payoffs from restricted stock, which in turn are more risky than base salaries. Risk-averse and undiversified executives will naturally place a lower value on riskier forms of compensation, and yet most studies of executive pay simply (and blindly) add together these different forms of compensation. The “risk premia” that executives attach to different forms of compensation depend on unobservable characteristics such as risk aversion and diversification, and it is not obvious how to add or how to weight the various components.

2.1.1 “Grant-Date” vs. “Realized” Pay

While the ultimate value of stock awards and stock options is not known until the stock vests and the options are exercised, these equity awards clearly have a value upon grant. Perhaps the most critical choice facing researchers in executive compensation is whether to measure the compensation associated with equity awards as the amount actually realized upon vesting and exercise, or to assign an “ex ante” grant-date value. Most academic research on executive compensation since the mid-1980s has adopted the ex ante approach, valuing stock awards as the fair market value on the date of grant (i.e. the grant-date stock price multiplied by the number of shares granted), and valuing stock options on the grant date using some variant of the Black and Scholes (1973) formula.

When total compensation is measured using grant-date values, it is routinely referred to as expected compensation to distinguish it from realized compensation as measured at the time the stock vests and the options are exercised.3 However, calling the grant-date pay “expected” is somewhat loose:

• For restricted shares (i.e. shares to be delivered at a future point in time), the grant-date stock price is the discounted expected value only if there are no performance hurdles, no dividends (or if the executive receives dividends on restricted shares, which is common) and only if there is no risk of forfeiture (i.e. no risk that the employment relation is terminated by either party prior to vesting).

• For stock options, the Black–Scholes value is the discounted expected payoff of a non-forfeitable European option for an executive who can perfectly hedge away the risk of the option (or, alternatively, the expected payoff under the risk-neutral distribution discounted at the risk-free rate).

• As discussed below in Section 2.1.2, the grant-date value (for either stock or option awards) is not a measure of value from the perspective of risk-averse undiversified executives who cannot hedge away the risk. However, with appropriate adjustments for dividends, forfeiture, dilution, and (for options) early exercise, the grant-date value can be an appropriate estimate of the cost to the company of granting restricted stock or options.

Similarly, bonus plans have a “grant-date value” typically measured as the target bonus, paid when the company achieves (usually accounting-based) target performance. However, even when target performance equals expected performance, the target bonus is only the “expected bonus” when the rewards and penalties for surpassing or missing targets are symmetric.

To illustrate the distinction between grant-date and realized pay, suppose that a CEO’s compensation in 2010 and 2011 consisted of a salary of $500,000 paid each year, and 50,000 shares of restricted stock awarded at the beginning of 2010 that become non-forfeitable (“vest”) at the end of 2011. Suppose further that the company’s stock price rose from $10 to $30 over the course of these two years. This CEO’s grate-date pay (which includes the grant-date value of the restricted stock) was $1000,000 in 2010 (consisting of the 2010 $500,000 base salary and the unvested stock with a grant-date value of $500,000) and the 2011 salary of $500,000. But, his realized pay (consisting of his base salary plus the amount realized upon vesting) was $500,000 in 2010 and $2000,000 in 2011 ($500,000 in base salary plus $1500,000 from the vesting of his stock at the end of 2011).

Grant-date and realized pay are both legitimate measures of CEO compensation and each is a legitimate answer to a different question. Compensation committees evaluating the competitiveness of their CEO pay package at the beginning of the year (that is, before performance results are tallied) should focus on grant-date pay levels. In contrast, realized pay levels will (by definition) depend on the company’s current and past performance, and are therefore most useful in evaluating whether ultimate rewards have been commensurate with company performance.

The distinction between grant-date and realized pay is also critical for researchers estimating the link between pay and performance. For example, researchers beginning with (I confess, reluctantly) Murphy (1985) have assessed the relation between pay and performance by regressing total grant-date compensation on measures of corporate performance (using CEO fixed-effects or first-differences to control for unobservable factors affecting pay levels). However, consider two otherwise identical executives, the first paid $1 million annually in base salary and the second paid $1 million annually in restricted shares. Researchers regressing grant-date pay levels on performance would conclude that neither executive is paid for performance, when in fact the second CEOs realized pay is strongly related to performance.

The SEC has helped confuse the distinction between grant-date and realized compensation by conflating elements of each in the “Summary Compensation Table” required in corporate proxy statements. In particular, since 2009, the SEC has required companies to report the grant-date fair-market values of stock and option grants in the Summary Compensation Table, while at the same time reporting the realized (rather than target) payouts from non-equity-based bonus plans. In addition, the SEC rules are particularly confusing for companies that pay annual bonuses partly in cash and partly in stock and options, as is common in financial services. As an example, suppose that a CEO receives a bonus of $10 million in January 2012 for performance in 2011, and that $4 million is paid in cash and the remaining $6 million in stock and options. According to SEC rules, the $4 million cash bonus is included as part of 2011 compensation (and reported in the firm’s 2012 proxy statement), while the $6 million bonus paid in the form of stock and options is included as part of 2012 compensation (and not reported until the firm’s 2013 proxy statement).

Adding to the confusion between grant-date and realized pay was the (thankfully temporary) existence of a third measure mandated by the SEC and included in the Summary Compensation Table in proxy statements issued between 2007 and 2009 (covering compensation paid between 2006 and 2008). Under the SEC’s 2007–2009 reporting requirements, “SEC Total Compensation” included the accounting expense the company records for stock and options during the year under Financial Accounting Standard 123R (FAS 123R) discussed below in Section 3.8.4. Using the accounting expense for valuing options instead of the grant-date value of options was a last-minute change to the reporting requirements made by the SEC in December 2006 without public comment. Under the SEC approach that mandates the use of accounting numbers in the table, the grant-date value of the $500,000 grant vesting in two years is reported as $250,000 in the grant year and $250,000 in the following year—numbers that bear no meaningful economic relationship to anything in the system. Fortunately, the confusion was relatively short-lived: in late 2009 the SEC revised its disclosure rules to include grant-date values rather than annual accounting expenses in the summary pay table.

Another element of the confusion in describing the typical CEO pay package reflects the statistical distinction between averages and medians. Suppose, for example, that there are eleven CEOs in an industry, ten receiving compensation of $1 million and the eleventh receiving $12 million. The average compensation in this industry is $2 million (calculated by summing all compensation amounts and dividing by 11), while the median is only $1 million (calculated as the compensation where half the CEOs are paid more and half the CEOs are paid less). Average and median pay are, again, both legitimate measures of CEO pay, but are answers to different questions. Average pay is relevant in assessing aggregate levels of pay (a reader can multiply the average pay by the number of CEOs and get total compensation paid to all CEOs), while median pay is more relevant in describing compensation for a “typical” CEO.

Figure 1 illustrates the 2011 grant-date and realized compensation for CEOs in firms listed in Standard and Poors S&P 500 (essentially the largest 500 US firms ranked by market value). The data are based on proxy statement information reported in Standard & Poors’ ExecuComp database for the 465 S&P 500 firms.4 For both measures, total compensation is comprised of six basic components: (1) base salaries; (2) discretionary bonuses; (3) non-equity incentives (based on both annual and multi-year performance measures); (4) stock options; (5) stock awards; and (6) other pay.5 Base salaries and the payouts from discretionary (non-formulaic) bonuses are the same for both grant-date and realized total compensation. However, the definitions of the remaining pay components vary with the measure utilized.

Figure 1 2011 pay for CEOs in S&P 500 companies. Note:Figure 1 is based on proxy statement information compiled in Standard & Poors’ ExecuComp database for 465 S&P 500 firms with fiscal closings between June 2011 and May 2012, based on ExecuComp’s May 2012 update. Grant-date Pay: Base Salary and Discretionary Bonus reflects amounts actually received for the fiscal year. Non-Equity Incentives evaluated at target level (or average of minimum and maximum if target not reported). Stock Options evaluated at grant-date using firm-estimated present value (typically Black and Scholes (1973) calculations). Stock Awards evaluated at grant-date using firm-estimated present value (typically grant-date market price), including both time-lapse restricted stock and performance shares. Other Compensation includes perquisites, signing bonuses, termination payments, above-market interest paid on deferred compensation, and the change in the actuarial value of pension benefits. Realized Pay: Base Salary and Discretionary Bonus reflects amounts actually received for the fiscal year. Non-Equity Incentives defined as payouts during the fiscal year (including payouts on awards made in prior years). Stock Options defined as gains executive realized by exercising options during the fiscal year. Stock Awards defined as value of awards vesting during the fiscal year (valued on the date of vesting). Other Compensation includes perquisites, signing bonuses, termination payments, above-market interest paid on deferred compensation, and pension benefits paid during the year. The pay-composition percentages for Average Compensation are calculated as the average ratio of each component to total compensation for each CEO. The composition percentages for Median Compensation are calculated as the median ratio of each component: median ratios do not sum to 100% (because the sum of the medians is not the median of the sum).

For grant-date pay, non-equity incentives are evaluated at the target level of payout (or, calculated as the average of the minimum and maximum payout if the target is not reported).6 The grant-date value of stock options is defined as the company’s estimate of the present value of the options on the grant-date: this value is typically based on Black and Scholes (1973) or similar methodologies and approximates the amount an outside investor would pay for the option. Similarly, the grant-date value of stock awards is calculated as of the grant date using the grant-date market price, which in turn approximates the amount an outside investor would pay for the stock. “Other compensation” includes perquisites, signing bonuses, termination payments, and above-market interest paid on deferred compensation. In addition, “other compensation” includes the change in the actuarial value of pension benefits, which typically constitutes a large percentage of compensation for those executives with supplementary defined-benefit pension plans.7

For realized pay, non-equity incentives are defined as actual payouts during the fiscal year, including both amounts paid in formula-based annual bonus plans, and current-year payouts from longer-term plans. Stock options are calculated as the gains realized by exercising options during the year, and stock awards are calculated as the value of the stock (or other equity instruments) as of the vesting date. Other compensation includes perquisites, signing bonuses, termination payments, above-market interest paid on deferred compensation, and the actual payments made to the CEO during the year under pension or retirement plans.

The first two columns in Figure 1 depict average grant-date and realized compensation. The pay-composition percentages are constructed by first calculating the composition percentages for each CEO, and then averaging across CEOs. The average grant-date CEO Pay in S&P 500 firms in 2011 was $11.6 million, compared to average realized pay of $12.3 million. Stock awards are the largest single component of both grant-date and realized pay in 2011. The “Other Pay” component of grant-date pay is large compared to the corresponding component for realized pay, reflecting that the definition of grant-date pay includes the (generally positive) change in the actuarial present value of pension benefits during the year. In contrast, the realized pay for pensions include only pension benefits paid during the year for proxy-named executives (which excludes amounts to be paid after retirement).

The remaining two columns in Figure 1 depict median compensation. The composition percentages for median pay are calculated as the median ratio of each component: median ratios do not sum to 100% (because the sum of the medians is not the median of the sum). Median compensation is typically lower than average pay, since a small number of very-highly paid CEOs will increase the average pay but not the median pay. For example, ConocoPhillips’s CEO James Mulva realized $141 million through exercising stock options in 2011. If the options had not been exercised, his pay would have fallen to “only” $5.3 million, and the average realized compensation for the 465 executives in Figure 2.1 would fall $303,000 from $12.436 million to approximately $12.133 million. Equity awards for the median executive are dominated by stock (rather than option) awards, and together option and stock awards comprise about half of total compensation for the typical executive.

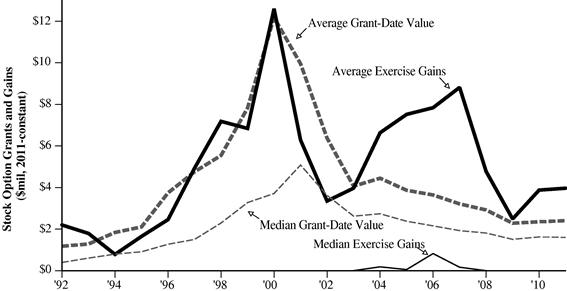

The difference between grant-date and realized values, and averages and medians, is especially pronounced for stock options. Figure 2 shows the average and median grant-date values and exercise gains (i.e. realized values) for stock options granted to or exercised by CEOs in S&P 500 firms from 1992 to 2011. As shown in the figure, the average grant-date values (dotted line) and exercise gains (solid line) were remarkably similar leading up to the 2000 burst in the Internet bubble. In contrast, average exercise gains increased while average grant-date values fell leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, reflecting the shift in grants primarily reflecting the shift from options to restricted stock described in more detail below.

Figure 2 Average and Median Stock Option Grant-Date Values and Exercise Gains for CEOs in S&P 500 Firms, 1992–2011. Note: Grant-date values based on company fair-market valuations, when available, and otherwise based on ExecuComp’s modified Black–Scholes approach. Dollar amounts are converted to 2011-constant dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

Figure 2 shows that median grant values and exercise gains were always below their respective averages. Interestingly, the median exercise gain was zero except for in the 2004–2007 period, indicating that less than half of the S&P 500 CEOs exercised options during most years in the sample (including 2000, when the average gain across all S&P 500 CEOs exceeded $12 million).8

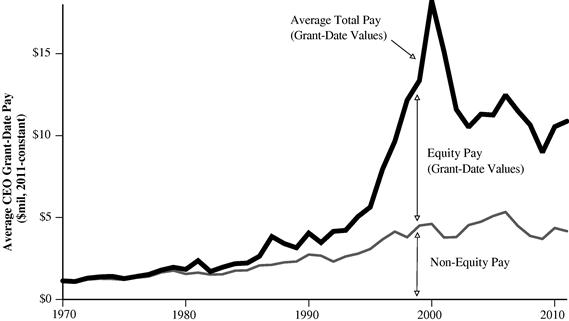

Figure 3 shows how average grant-date pay for CEOs has evolved from 1970 to 2011. The data are adjusted for inflation and are based on information extracted from annual Forbes surveys (1970–1991) and Standard & Poors ExecuComp Database (1992–2011).9 Non-equity pay includes base salaries, payouts from short-term and long-term bonus plans, deferred compensation, and benefits. Total compensation includes non-equity compensation plus equity-based compensation, including the grant-date values of stock options and restricted stock.10 Due to changing reporting requirements and data availability some of the estimates of grant-date compensation are approximations, but the trends depicted in Figure 3 are nonetheless historically representative. As shown in the figure, average grant-date compensation increased from about $1.1 million in 1970 to $10.9 million in 2011, down from a peak of $18.2 million in 2000.11 Finally, the figure shows that most of the growth in CEO pay since 1990 is explained by the growth in equity-based pay. Indeed, stock and options constituted only a trivial percentage of pay in the early 1970s, and grew to be the dominant form of pay by the late 1990s.

Figure 3 Average Equity and Non-equity Grant-Date Pay for CEOs in S&P 500 Firms, 1970–2011. Note: Compensation data are based on all CEOs included in the S&P 500, using data from Forbes and ExecuComp. CEO total pay includes cash pay, restricted stock, payouts from long-term pay programs and the value of stock options granted (using company fair-market valuations, when available, and otherwise using ExecuComp’s modified Black–Scholes approach). Average (median) equity compensation prior to 1978 estimated based on option compensation in 73 large manufacturing firms (based on Murphy (1985)), equity compensation from 1979 through 1991 estimated as amounts realized from exercising stock options during the year, rather than grant-date values. Non-equity incentive pay is based on actual payouts rather than targets, since target payouts were not available prior to 2006. Dollar amounts are converted to 2011-constant dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

Figure 4 shows how both the composition and level of grant-date pay evolved from 1992 to 2010. Because of the skewness in the pay distribution (where a small number of CEOs receive unusually high levels of compensation), the median pay in Figure 4 is significantly lower than the average pay in Figure 3 in each year. The pay-composition percentages in the figure are constructed by first calculating the composition percentages for each CEO, and then averaging across CEOs. As evident from the figure, underlying the growth in pay for CEOs since the 1990s is an escalation in stock-option compensation from 1993 to 2001 coupled with a dramatic shift away from options towards restricted stock from 2002 to 2011. In 1992, base salaries accounted for 41% of the $2.9 million median CEO pay package, while stock options (valued at grant-date) accounted for 25%. By 2001, base salaries accounted for only 18% of the median $9.2 million pay, while options accounted for more than half of pay. By 2011, options fell to only 21% of pay, as many firms switched from granting options to granting restricted stock (which swelled to 36% of pay).

Figure 4 Median Grant-date Compensation for CEOs in S&P 500 Firms, 1992–2011. Note: Compensation data are based on all CEOs included in the S&P 500, using data from ExecuComp. CEO grant-date pay includes cash pay, payouts from long-term pay programs, and the grant-date value of stock and option awards (using company fair-market valuations, when available, and otherwise using ExecuComp’s modified Black–Scholes approach). Monetary amounts are converted to 2011-constant US dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

In interpreting the time-series in Figure 4, it is important to recognize the selection bias inherent in the S&P 500. In particular, the firms in the index are selected by a committee based primarily on market capitalization and industry representation. For example, during the 1990s the S&P 500 increased its representation of “new economy” firms, as these firms became more highly valued and a more important component of the economy.12 Indeed, the fraction of the S&P 500 comprised of new economy firms grew from 5.5% in 1992 to over 12% in 2001 (and remained at about 11% for the rest of the sample period). Since new economy firms have traditionally relied on stock options as a major component of pay (see Murphy, 2003), the increase in both the level of pay and the use of options in Figure 4 in part reflects changes in the composition of the S&P 500.

Figure 5 replicates Figure 4 after restricting the sample to only firms included in the S&P 500 in 1992. This sample restriction attenuates the increase in pay levels, which increased by 165% from 1992 to 2000 (instead of 220% as in Figure 4). The figure also suggests that CEO pay continued to increase until 2007 (a starkly different pattern than suggested by Figure 4). However, while Figure 5 mitigates the S&P 500 selection bias in Figure 4, it is subject to a survivor bias: only half of the S&P 500 firms in 1992 were still publicly traded in 2011.

Figure 5 Median Grant-date Compensation for CEOs in Firms Included in the 1992 S&P 500 Note: Compensation data are based on all CEOs included in the 1992 S&P 500, using data from ExecuComp. The sample size varies from 472 in 1992 to 260 in 2011. CEO grant-date pay includes cash pay, payouts from long-term pay programs, and the grant-date value of stock and option awards (using company fair-market valuations, when available, and otherwise using ExecuComp’s modified Black–Scholes approach). Monetary amounts are converted to 2011-constant US dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

While the analysis in this chapter will generally focus on S&P 500 companies, Figure 6 shows the evolution of the level and compensation for CEO pay below the S&P 500. The data, extracted from ExecuComp, include firms in the S&P MidCap 400, S&P SmallCap 600, and a small number of other firms tracked by S&P. As evident by comparing Figures 4 and 6, the level of CEO pay below the S&P 500 is considerably smaller than pay levels for S&P 500 CEOs. In addition, while median pay for S&P 500 CEOs has more than tripled from 1970–2010, pay for CEOs below the S&P 500 merely doubled. Similar to their S&P 500 counterparts, restricted stock has replaced stock options as the primary form of equity-based compensation.

Figure 6 Median Grant-date Compensation for CEOs in non-S&P 500 Firms, 1992–2011. Note: Compensation data are based on all CEOs included in the S&P MidCap 400, SmallCap 600, and a small number of other non-S&P 500 firms tracked by S&P and included in the ExecuComp database. CEO grant-date pay includes cash pay, payouts from long-term pay programs, and the grant-date value of stock and option awards (using company fair-market valuations, when available, and otherwise using ExecuComp’s modified Black–Scholes approach). Monetary amounts are converted to 2011-constant US dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

2.1.2 The “Cost” vs. the “Value” of Incentive Compensation

In constructing measures of total compensation, it is important to distinguish between two often confused but fundamentally different valuation concepts: the cost to the company of granting the compensation and the value to an executive of receiving the compensation. Consider, for example, a company that decides to give a share of restricted stock to its CEO vesting in five years (that is, the CEO is restricted from selling the share of stock for five years, and receives the accumulated dividends [plus interest] upon vesting). Suppose further that the market price of a share of stock is $10. The economic or opportunity cost of the stock grant to the company is the amount the company could have received if it were to sell an unrestricted share to an outside investor rather than giving the restricted share to the CEO. Ignoring the probability of forfeiture and the slight dilution discount associated with issuing a new share, the company could raise $10 by selling the share to an outside investor. Thus, the company’s cost of granting the share is the price of the share on the open market.

Alternatively (but equivalently), by granting the restricted share to the CEO, the company is effectively promising to deliver one share of stock to the CEO in five years. If the company had no shares available to issue, it could satisfy this contract by purchasing a share on the open market in five years at a price that might be higher or lower than $10. If the company wanted to perfectly hedge the “price risk” of its future obligation, it could purchase a share of stock in the open market today (for $10) and deliver it to the CEO in five years. Thus, again, the company’s cost of granting the share is simply the price of the share on the open market.

But, what about the CEO? The CEO would clearly prefer to have $10 today than a promise to receive one share of stock in five years; after all, he could always take the $10 and buy a share of stock today, but will likely have other more-preferred uses for the $10. Moreover, if the CEO is risk averse and undiversified (in the sense that his overall wealth is positively correlated with company stock prices, through existing stock ownership, option holdings, and the risk of being fired for poor performance), the value the CEO places on the share of restricted stock will be strictly less than the fair market value of the share. Note that the CEO’s value will predictably decrease as the CEO becomes more risk averse or less diversified.

Similarly, suppose that the company decides to give the CEO an option to buy a share of stock at a predetermined exercise price. The opportunity cost of granting the option is the amount an outside investor would pay for it. The outside investor is generally free to trade the option, and can also take actions to hedge away the risk of the option (such as short-selling the underlying stock). Black and Scholes (1973) and Merton (1973) demonstrated that, since investors can hedge, options can be valued as if investors were risk neutral and all assets appreciate at the risk-free rate. This risk-neutrality assumption forms the basis of option pricing theory and is central to all option pricing models, including binomial models, arbitrage pricing models, and Monte Carlo methodologies. Ignoring dilution, forfeiture, and early exercise, these now-standard methodologies provide reasonable estimates of what an outside investor would pay, and therefore measure the company’s cost of granting options.

Measures of opportunity cost that ignore dilution, forfeiture, and early exercise will systematically overstate the company’s cost of granting options. Dilution reduces the cost of granting options because companies typically issue new shares when options (technically, warrants) are exercised. While the impact of dilution on any specific option grant is typically immaterial, the impact can be significant when added across all employees receiving options. Forfeiture reduces the cost because executives typically forfeit some or all of their unexercisable options upon resignation or termination.13 Most importantly, Ballowing executives to exercise options before they expire reduces the company’s cost of granting options because risk-averse employees—seeking diversification and liquidity—predictably exercise non-tradable options sooner than would an outside investor holding a tradable option.

However, even after appropriate adjustments for dilution, forfeiture, and early exercise, Black–Scholes values do not measure the value of the non-tradable option to a risk-averse executive. In contrast to outside investors, company executives cannot trade or sell their options, and are also forbidden from hedging the risks by short-selling company stock. In addition, while outside investors tend to be well-diversified (holding small amounts of stock in a large number of companies), company executives are inherently undiversified, with their physical as well as human capital invested disproportionately in their company. For these reasons, company executives will generally place a much lower value on company stock options than would outside investors.

Lambert, Larcker, and Verrecchia (1991) and Hall and Murphy (2002) propose measuring the value of a non-tradable option to an undiversified risk-averse executive as the amount of riskless cash compensation the executive would exchange for the option.14 Suppose that an executive has non-firm-related wealth of w, holds a portfolio S(·) of company shares and options, and is granted n options to buy n shares of stock at exercise price X in T years. Assuming that w is invested at the risk-free rate, rf, and that the realized stock price at T is PT, the executive’s wealth at time T is given by

![]() (1)

(1)

If, instead of the option, he were awarded V in cash that he invested at the risk-free rate, his wealth at time T would be:15

![]() (2)

(2)

Assuming that the executive’s utility over wealth is U(W), we can define the executive’s value of n options as the “certainty equivalent” V that equates expected utilities (1) and (2):

![]() (3)

(3)

Solving (3) numerically requires assumptions about the form of the utility function, U(W), and the distribution of future stock prices, f(PT). I follow Hall and Murphy (2002) in assuming that the executive has constant relative risk aversion ρ, so that ![]() when ρ = l, and

when ρ = l, and ![]() when

when ![]() . I adopt the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and assume that the distribution of stock prices in T years is lognormal with volatility σ and expected value equal to

. I adopt the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and assume that the distribution of stock prices in T years is lognormal with volatility σ and expected value equal to ![]() , where β is the firm’s systematic risk and rm is the return on the market portfolio.16

, where β is the firm’s systematic risk and rm is the return on the market portfolio.16

Calculating certainty equivalents from (3) requires data on stock and option grants and holdings (available from corporate proxy statements17), and also requires unobservable data on executive “safe wealth” (i.e. wealth not correlated with company stock prices) and executive risk aversion. Following Hall and Murphy (2002), I assume that CEOs have relative risk-aversion parameters of 2 or 3, and that each CEO has “safe wealth” equal to the greater of $5 million (in 2011-constant dollars) or four times the current cash compensation.18 For other inputs, I assume a market risk premium of 6.5%, set the risk-free rate to the yield on 7-year US Treasuries, estimate dividend yields as the average yield over the past 36 months and volatilities based using the last 48 months of stock returns. Dividend yields above 5% are set to 5%, while volatilities below 20% or above 60% are set to 20% and 60%, respectively. As a simplifying assumption, I assume that the term for all options and restricted stock grants equals the term on the largest option grant (or five years if no options are granted), and assume that the executive’s prior holdings of stock and options are fixed throughout the term of the new grants. Finally, I assume (somewhat arbitrarily) that the risk-adjusted value of accounting-based bonuses is worth 90% of target bonuses.

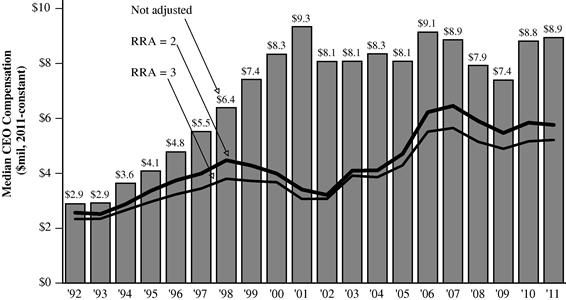

Figure 7 shows the 1992–2011 evolution of risk-adjusted pay for CEOs in S&P 500 firms, assuming constant relative risk aversion of 2 or 3. The bar height depicts median pay without risk adjustments from Figure 4. Several features of the figure are worth noting:

• The value of compensation from the perspective of risk-averse undiversified CEOs can be substantially less than the cost of compensation reported in company proxy statements. For example, in 2001 (at the peak of the use of stock options), the median risk-adjusted pay for CEOs with constant relative risk aversion of 3 ($2.6 million) was less than one third of the median reported pay ($9.3 million).

• While reported pay levels increased significantly between 1998 and 2001 (driven primarily by the escalation in the grant-date values of stock options), risk-adjusted pay actually fell over this time period as a larger percentage of pay was being delivered in the form of risky stock options.

• Similarly, while reported pay levels were relatively flat from 2002 to 2007, risk-adjusted pay grew substantially as risky stock options were increasingly replaced by less-risky stock awards.

Figure 7 Median Risk-Adjusted Pay for CEOs in non-S&P 500 Firms, 1992–2011. Note: Risk-adjusted pay is estimated using the “certainty equivalence” approach, estimated numerically assuming that the executive has constant relative risk aversion (rra) of 2 or 3, and assuming (using the Capital Asset Pricing Model) that the distribution of stock prices over the actual term of the options granted is lognormal with volatility σ and expected value ![]() , where σ and β are determined using monthly stock-return data over 48 months, rf is the country-specific average yield on government securities during the year of grant, and

, where σ and β are determined using monthly stock-return data over 48 months, rf is the country-specific average yield on government securities during the year of grant, and ![]() is the market risk premium. assuming relative risk aversion of 2 or 3; safe wealth is assumed to be the greater of $5 million or four times total compensation (in 2011-constant dollars). The risk-adjusted value of accounting-based bonuses is assumed to be worth 90% of actual bonuses.

is the market risk premium. assuming relative risk aversion of 2 or 3; safe wealth is assumed to be the greater of $5 million or four times total compensation (in 2011-constant dollars). The risk-adjusted value of accounting-based bonuses is assumed to be worth 90% of actual bonuses.

The qualitative results in Figure 7 are robust to alternative definitions of risk aversion, safe wealth, equity premiums, and option terms. Calculating more precise estimates of risk-adjusted compensation for individual CEOs requires unavailable data on outside wealth and unobservable measures of individual risk aversion. In addition, more-precise estimates should allow CEOs to invest outside wealth in the market portfolio (Cai and Vijh, 2005) and allow for early exercise and different vesting and exercise terms of current grants and existing holdings. Nonetheless, the results in Figure 7 highlight that inferences based on reported grant-date compensation do not necessarily extend to risk-adjusted compensation.

2.2 Measuring Executive Incentives

Conceptually, the incentives created by any compensation plan are determined by two factors: (1) how performance is measured; and (2) how compensation (or wealth) varies with measured performance. Most of the executive compensation literature has focused on the relation between CEO and shareholder wealth (or, what Jensen and Murphy (1990b) defined as the “pay-performance sensitivity”), where CEOs with higher pay-performance sensitivities are defined as having better incentives to create shareholder value. Therefore, I begin this section with an analysis of different ways to measure the incentives that executives have to increase shareholder wealth. Next, given the recent focus on excessive risk-taking which many believe contributed to the financial crisis, I consider two measures of the incentives that executives have to increase stock-price volatilities. Finally, I discuss a variety of other incentive problems not neatly encapsulated in pay-performance or pay-volatility sensitivities, such as incentives to smooth or manage earnings or to pursue short-run profits at the expense of long-run value.

2.2.1 The Relation Between CEO and Shareholder Wealth

Most research on CEO incentives has been firmly (if not always explicitly) rooted in agency theory: compensation plans are designed to align the interests of risk-averse self-interested CEOs with those of shareholders. Following this framework, most of the focus has been on the relation between CEO compensation (or CEO wealth) and changes in firm value. Researchers have often used the ratio of equity-based total compensation to total compensation as a measure of incentives. However, the most direct linkage between CEO and shareholder wealth comes from the CEO’s holdings of stock, restricted stock, and stock options. CEO wealth is also indirectly tied to stock-price performance through accounting-based bonuses (reflecting the correlation between accounting returns and stock-price performance), through year-to-year adjustments in salary levels, target bonuses, and option and restricted stock grant sizes, and through the threat of being fired for poor stock-price performance. The CEO pay literature has yet to reach a consensus on the appropriate methodologies and metrics to use in evaluating the “indirect” relation between CEO pay and company stock-price performance. For practical purposes, however, Hall and Liebman (1998) and Murphy (1999) show that virtually all of the sensitivity of pay to corporate performance for the typical CEO is attributable to the direct rather than the indirect part of the CEO’s contract, and the direct part can be measured from information available in corporate proxy statements.

Since agency costs arise when agents receive less than 100% of the value of output, the CEO’s share of ownership is a natural measure of the potential severity of the agency problem. In particular, the CEO’s percentage holdings of his company’s stock measures how much the CEO gains from a $1 increase in the value of the firm, and how much he loses from a $1 decrease. Computing percentage ownership for restricted and unrestricted shares is trivial (simply divide by the total number of shares outstanding). Including stock options in a percentage holdings measure is more complicated, since options that are well out-of-the-money provide few incentives to increase stock prices, while options that are well in-the-money provide essentially the same incentives as holding stock. Therefore, each stock option should count somewhat less than one share of stock when adding the holdings to form an aggregate measure of CEO incentives, and the “weight” should vary with how much the option is in (or out) of the money. In constructing an aggregate measure of CEO incentives, I weight each option by the “Option Delta”, defined as the change in the value of a stock option for an incremental change in the stock price. Option Deltas range from near zero (for deep out-of-the-money options) to near one (for deep in-the-money options on non-dividend paying stock).19 I call our measure the “effective ownership percentage” to distinguish it from the actual ownership percentage based only on stock (and not option) holdings.

Figure 8 shows the evolution of the median effective percentage ownership for CEOs in S&P 500 firms from 1992 to 2011. The percentage ownership for stock and restricted stock is calculated by dividing the CEOs shareholdings by the total number of shares outstanding. Effective percentage ownership for stock options is measured by weighting each option held by the executive at the end of the fiscal year by “Option Delta” for that option (which varies according to the exercise price and time remaining to exercise), and dividing by the total number of shares outstanding.20 As shown in the figure, stock and restricted stock holdings for the median S&P 500 executive has grown modestly over the 20-year period (reflecting the increased popularity of restricted stock), ranging from 0.12% to 0.15%. Over the same time period, total effective ownership (including delta-weighted options) doubled from 0.35% in 1992 to 0.69% in 2003, before falling to 0.38% in 2011. The drop in ownership in 2008 depicted in Figure 8 primarily reflects that most options held by CEOs at the end of 2008 were substantially out of-the-money and therefore had low incentives and low Option Deltas.

Figure 8 Median Effective Percentage Ownership for CEOs in S&P 500 Firms, 1992–2011. Note: Percentage ownership for stock and restricted stock measured as the CEO’s shareholdings divided by the total number of shares outstanding. Effective percentage ownership for stock options measured by weighting each option held by that options “Black–Scholes Delta” and dividing by the total number of shares outstanding. Year-end options under the pre-2006 disclosure rules estimated using the procedure described in Murphy (1999).

The measure of effective CEO ownership in Figure 8 is essentially the “Pay-Performance Sensitivity” introduced by Jensen and Murphy (1990b). The primary difference is that I am measuring the effective ownership percentage, while Jensen and Murphy measured the change in CEO wealth per $1000 change in shareholder wealth, which equals the effective ownership percentage multiplied by ten. The other difference is that Jensen and Murphy also include indirect incentives from cash compensation and disciplinary terminations. Using data from 1974 to 1986, Jensen and Murphy estimate a median pay-performance sensitivity for stock and options of $2.50 for every $1000 change in shareholder wealth, which corresponds to an ownership percentage of 0.250%.21 Therefore, by the end of 2003, pay-performance sensitivities had nearly tripled the data from 1974 to 1986. But, by year-end 2011 the pay-performance sensitivity was slightly above its 1992 level, or about 50% higher than the Jensen–Murphy estimate.

The average market capitalization of firms in the S&P 500 grew (in 2011-constant dollars) from $10.0 billion in 1992 to $35.8 billion in 2000 (before falling to $22.7 billion in 2011), therefore the dollar value of the typical CEOs ownership position is large even if his percentage holding is low. Hall and Liebman (1998) argue that a better way to measure CEO incentives is as the change in CEO wealth for a 1% change in the value of the firm rather than as the ownership percentage. Baker and Hall (2004) provide some theoretical justification for using this measure. In particular, Baker and Hall show that percentage ownership is the right measure of incentives when the marginal product of the CEO effort is constant across firm size, such as a CEO contemplating a new corporate headquarters that will benefit the CEO but perhaps not the shareholders, or an outside takeover bid that will benefit outside shareholders but perhaps not the CEO. But, the Hall-Liebman measure is appropriate when the marginal product of the CEO effort scales with firm size, such as a corporate reorganization (assuming it takes the same amount of CEO effort to reorganize a big firm as a small firm).

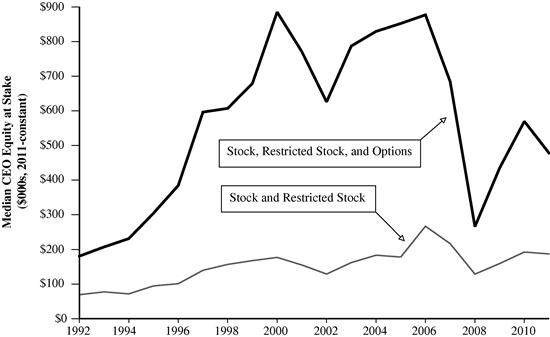

Figure 9 shows the evolution of the Hall-Liebman measure—what Frydman and Jenter (2010) call “equity at stake”—from 1992 to 2011. The equity-at-stake measure is calculated as 1% of the effective ownership percentage multiplied by the firm’s market capitalization.22 In 1992, each 1% change shareholder wealth resulted in a $181,000 change in CEO wealth for the median CEO in the S&P 500. The equity-at-stake measure grew to nearly $900,000 in 2000 and again in 2005, before plummeting to $265,000 in 2008 as a result of both the decline in market capitalizations and the decline in Option Deltas.

Figure 9 Median Equity at Stake for CEOs in S&P 500 Firms, 1992–2011. Note: Following Frydman and Jenter (2010), Equity-at-Stake is measured as the effective ownership percentage multiplied by 1% of the firms market capitalization (in thousands of 2011-constant dollars).

As an alternative to both the Jensen-Murphy and Hall-Liebman measures, Edmans, Gabaix, and Landier (2009) provide theoretic justification for measuring incentives using the “wealth-performance elasticity” (i.e., the percentage change in CEO wealth corresponding to a percentage change in firm value) when the CEO effort has a multiplicative (rather than additive) effect on both CEO utility and firm value. In practice, creating this measure generally requires data not available to researchers (in particular, the CEO’s wealth beyond his portfolio of company stock and options).23

2.2.2 The Relation Between CEO Wealth and Stock-Price Volatilities

Suspicions that executive compensation policies in financial services firms contributed to the 2008-2009 financial crisis eventually broadened to similar suspicions for companies outside the financial sector. In December 2009, as part of the continued fallout from the crisis, the SEC began requiring all publicly traded companies to disclose and discuss compensation policies and practices that might provide incentives for executives to take risks that are reasonably likely to have a materially adverse effect on the company.

When executives receive rewards for upside risk, but are not penalized for downside risk, they will naturally take greater risks than if they faced symmetric consequences in both directions. For top executives, rewarded primarily with equity-based compensation, the primary source of risk-taking incentives emanates from stock options. The pay-performance relation implicit in stock options is inherently convex, since executives receive gains when stock prices exceed the exercise price, but their losses when the price falls below the exercise price are capped at zero.

Since equity is a “call option” on a leveraged firm (Black and Scholes, 1973), equity-based pay in a leveraged firm can provide similar risk-taking incentives to those provided by stock options in an all-equity firm. Consider, for example, an investment opportunity promising equal chances of a $400 million gain and a $600 million loss (i.e. a net-present value of -$100). Shareholders in a $1 billion all-equity firm will have no incentive to pursue this negative NPV investment, because they will bear 100% of both the gains and losses. But, suppose the firm has only $100 million in equity, and $900 million in debt. Equity holders receive 100% of the upside, but their downside liability is limited to the value of their initial equity stake ($100 million). Thus, from the perspective of the equity holders, the project has a net present value of +$150 million.

The conflict of interest between shareholders and debtholders—dubbed the “Agency Cost of Debt” by Jensen and Meckling (1976)—has led several researchers to measure risk-taking incentives by leverage ratios and to prescribe CEO pay structures that include debt as well as equity.24 However, it is worth noting that it is not leverage per se that creates risk-taking incentives, but rather the limited liability feature of equity. For example, the shareholders in the example in the prior paragraph would have incentives to take the negative NPV project even if the firm was a $100 million all-equity firm; in this case losses greater than $100 million would be borne by the government or society, etc., and not by debtholders. It is also worth noting that the severity of the risk-taking incentives depends on the maximum downside risk compared to the dollar amount of equity, and not the value of equity compared to the overall value of equity plus debt. The level of debt is important only to the extent that is available to fund risky negative NPV projects.

Since the value of a stock option (or the value of equity in a leveraged firm) increases monotonically with stock-price volatilities, options (and limited liability) provide incentives for executives to increase such volatilities. In Section 2.2.1, the calculations for pay-performance sensitivities for stock options depended on the Option Delta, defined as the change in the value of a stock option associated with an incremental change in the stock price. Similarly, the calculations for pay-volatility sensitivities for stock options depend on the Option Vega, typically defined as the change in the value of a stock option associated with one percentage-point increase in the stock-price volatility (e.g. from 30% to 31%). Option Vegas are typically highest when stock prices are near the option’s exercise price.

Following Fahlenbrach and Stulz (2011)’s analysis of executive compensation and the financial crisis, I consider two option-based measures for incentives to increase stock-price volatilities:

![]()

![]()

Figure 10 shows the time trends in the two measures of pay-volatility sensitivities for the median executive in a S&P 500 firm from 1992 to 2011. The left-hand axis reports the Total Option Vega, which reached its peak in 2003 (when the median CEO gained $243,000 by increasing volatility by one percent), and plummeted in 2008 to $127,000 for a one percent increase in volatility. The right-hand axis reports the percentage change in option values associated with a one percent increase in volatility. This “Vega Elasticity” remained relatively constant from 1992 to 2007 at around 1.0 (indicating that a one percentage-point increase in volatility would increase the value of CEO option holdings by about 1%). The Vega Elasticity jumped to over 5.0% in 2008, falling to 2.0% by 2011.

Figure 10 Option-based incentives to increase volatility by CEOs in S&P 500 Firms, 1992–2011. Note: The Total Option Vega is defined as the change in value of outstanding options for a one percentage-point increase in volatility. Vega Elasticity is defined as the percentage change in value of outstanding options for a one percentage-point increase in volatility.

The differences in the two measures in Figure 10 reflect the effect of stock-market movements and, in particular, the market crash at the end of 2008 and the partial rebound by 2011. When stock prices fell (as they did abruptly in 2008, across all sectors of the economy), the options fell out of the money, which implies that the Option Vega for each option becomes smaller (remember that the Option Vega is highest when the stock price is close to the exercise price). But, it turns out that, as stock prices fall, the value of the options held fall even faster than the Option Vega. As a result, the value of options that are out-of-the-money increases more in percentage terms (but less in dollar or euro terms) as volatility increases.

One troublesome fact apparent from Figure 10 is that the two vega measures—both legitimate measures for risk-taking incentives—move in opposite directions in market downturns. There is no accepted methodology for measuring incentives for risk in executive option portfolios, or in executive equity positions in leveraged firms, or in executive contracts more generally.25 Until the recent financial crisis—when compensation policies were blamed for contributing to the meltdown—there had been little focus on the role of compensation policies in providing incentives to take risks.

Finally, while the current controversy over executive incentives has focused on excessive risk taking, it is worth noting that the challenge historically has been in providing incentives for executives to take enough risk, not too much risk. Executives are typically risk-averse and undiversified with respect to their own companies’ stock-price performance. On the other hand, shareholders are relatively diversified, placing smaller bets on a larger number of companies. As a result, executives will inherently be “too conservative” and want to take fewer risks than desired by shareholders. Stock options (or other plans with convex payouts) have long been advocated as ways to mitigate the effects of executive risk aversion by giving managers incentives to adopt rather than avoid risky projects (see, for example, Hirshleifer and Suh, 1992). Similarly, there is a long history of attempts to document an empirical relation between such convexities and actual risk-taking incentives, and the results have been relatively modest.26

2.3 (Dis)lncentives from Bonus Plans27

Most discussions about incentives for US CEOs focus exclusively on equity-based incentives, since changes in CEO wealth due to changes in company stock prices dwarf wealth changes from any other source (Hall and Liebman, 1998; Murphy, 1999). However, from a behavioral perspective, annual and multi-year bonus plans based on accounting measures may be as important as equity in actually directing the activities of CEOs and other executives. Consider the following:

• Incentive plans are effective only if the participants understand how their actions affect the payoffs they will receive and then act on those perceptions. While CEOs likely understand how to increase accounting income (by increasing revenues and decreasing costs of goods sold), they often do not understand how their actions affect company stock prices. Therefore, bonus plans may well provide stronger incentives than equity-based plans, even though their magnitude is smaller.

• Most bonus plans are settled in cash soon after the results are tallied (e.g. after the year-end audited financials). The immediacy and tangibility of these cash awards may well provide stronger incentives than the distant and uncertain paper gains in unvested equity plans.

Unfortunately, while CEOs may indeed be motivated by their bonus opportunities, they are not necessarily motivated to increase firm value. The problems lie in the design of the typical bonus plan, illustrated in Figure 11. Under the typical plan, no bonus is paid until a lower performance threshold or hurdle is achieved, and a “hurdle bonus” is paid at this lower performance threshold. The bonus is usually capped at an upper performance threshold; after this point increased performance is not associated with an increase in the bonus. The thresholds are routinely determined by the firm’s annual budgeting process. The range between the lower and upper performance thresholds (labeled the “incentive zone” in the figure), is drawn as linear but could be convex (bowl-shaped) or concave (upside-down bowl-shaped). The “pay-performance relation” (denoted by the heavy line) is the function that shows how the bonus varies throughout the entire range of possible performance outcomes.

Figure 11 A Typical Bonus Plan Note: Under a typical bonus plan, a performance target and a target bonus for meeting that performance are set. Upper and lower performance thresholds are established which create an incentive zone within which the bonus increases with performance. Bonuses do not vary with performance outside the range established by the Lower and Upper Performance thresholds. A Hurdle Bonus is often paid when the executive reaches the lower performance threshold. The bonus can increase linearly with performance in the incentive zone (as shown here) or it can increase at a decreasing rate or an increasing rate (that is, the line can be convex or concave).

In spite of substantial variability across companies and industries, short-term and long-term bonus plans can be characterized in terms of the three basic dimensions suggested by Figure 11: performance measures, performance thresholds (that is, targets, benchmarks, or standards), and the structure of the pay-performance relation. Design flaws in any of these dimensions can provide incentives to withhold effort, to shift earnings and cash flow unproductively from one period to another (or otherwise manipulate earnings), to use capital inefficiently, and to destroy information critical to the effective coordination of disparate parts of large complex firms.

2.3.1 Problems with Non-Linear Pay-Performance Relations

Researchers have long acknowledged that non-linear incentive plans cause predictable problems.28 For example, executives capable of producing well above the upper performance threshold in Figure 11 have incentives to stop producing once they “max out” on their bonuses. In addition, they will do their best to transfer performance results that could have been realized this period into a later period.

Similarly, but potentially worse, is the effect of the discontinuity at the lower performance threshold in Figure 11. Executives who believe they cannot achieve at least this level of performance this year will either stop producing or “save” performance for next year by delaying revenues or accelerating expenses. Moreover, if executives see that they are not going to make the bonus pool this year, they are better off taking an even bigger hit this period (since there is no bonus penalty for missing the lower threshold by a lot instead of a little) so they can do even better next period—what accountants have called the “big bath” phenomenon. On the other hand, executives who are struggling to make the lower threshold, but still believe they can make that threshold, have incentives (provided by the threshold bonus) to do whatever is necessary to achieve the lower threshold. Their actions commonly include destroying value by loading the distribution channel so as to recognize revenues earlier, unwisely reducing R&D and required maintenance expenditures, and (in some cases) outright accounting fraud. Each of these actions shifts reported profits from next period to the current period, but does so at an unnecessary cost to the firm.

In both of these cases, the non-linearities provide incentives for CEOs to “manage earnings”. In particular (and assuming that performance is measured by earnings), the bonus plan in Figure 11 provides incentives to “smooth earnings” (by shifting earnings from next period when below the lower threshold and shifting earnings to next year when above the upper threshold), while occasionally taking a “big bath” (when it is not possible, even with manipulation, to get earnings above the lower threshold).

In addition to earnings management, non-linearities also affect risk-taking behavior. In particular, when the pay-performance relation is concave (so that lower performance is penalized more than higher performance is penalized), executives can increase their total bonus payouts by reducing the variability of their performance. Conversely, convex pay-performance relations increase risk-taking incentives. Financial economists have suggested that boards purposely add convexity to CEO pay contracts to offset the reluctance of risk-averse CEOs to invest in risky (but profitable) projects.29 More recently, some academics (as well as Congress and the popular press) have alleged that convexities in banking bonuses (where positive performance is rewarded, but negative performance is not penalized) led to excessive risk-taking that, in turn, facilitated the 2008–2009 financial crisis.

The problems with non-linearities are mitigated by eliminating caps on the upside, and finding ways to implement and enforce “negative” bonuses on the downside.30 While it is difficult to force CEOs to write checks back to the company after a bad year, negative bonuses can be partially implemented by basing pay on multi-period cumulative performance (Holmstrom and Milgrom, 1987) or by deferring current compensation into bonus banks that can be used to fund future negative bonuses (Stewart, 1991). Another indirect way to impose negative bonuses is by reducing base salaries and offering enhanced bonus opportunities (through reduced bonus thresholds).

2.3.2 Problems with Performance Benchmarks

Bonuses are usually not, in practice, based strictly on a performance measure, but rather on performance measured relative to a performance benchmark (Murphy, 2000). Examples include net income measured relative to budgeted net income, EPS vs. last year’s EPS, cash flow vs. a charge for capital, performance measured relative to peer-group performance, or performance measured against financial or non-financial strategic “milestones”. Performance targets (one form of benchmark) typically correspond to the level of performance required to attain the executive’s “target bonus”.

When bonuses are based on performance relative to a benchmark, executives can increase their bonus either by increasing performance or lowering the benchmark. Performance benchmarks therefore create predictable problems whenever the participants in the bonus plan can affect the benchmark. For example, when benchmarks are based on meeting a budget, executives with bonuses tied to budgeted performance targets have strong incentives to low-ball the budget. Boards (and supervisors throughout the management hierarchy) understand these incentives and generally push for higher budgets than those suggested by executives. The result is a familiar and predictable “budget game” that ultimately destroys the information critical to coordinating the disparate activities of a large complex organization (Jensen, 2003).

As another example, when benchmarks are based on prior performance (such as bonuses based on growth or improvement), plan participants understand that increased performance this year will be penalized by higher benchmarks the next year, and will naturally take account of these dynamics when deciding how hard to work and what projects to undertake in the current year. Similarly, when bonuses are based on performance measured relative to that of colleagues, participants can increase their bonuses by sabotaging co-executives (Lazear, 1989; Gibbons and Murphy, 1990). Benchmarks based on industry peers provide incentives for selecting “weak” industries or peers, or staying too long in a defective industry (Dye, 1992).

The problems with benchmarks based on budgets, prior-year performance, co-workers, and other internally manipulable measures can be mitigated by “externalizing” the benchmark; that is, by basing the benchmark on objective measures beyond the direct control of the plan participants. In Murphy (2000), I showed that companies using external benchmarks (which I defined as benchmarks based on fixed numbers or schedules, industry performance, or the cost of capital) were less likely to manage fourth-quarter earnings than were companies with internal benchmarks. However, I was unable to explain satisfactorily cross-sectional differences in the use of internal and external benchmarks, or why nearly 90% of the sample of 177 firms based benchmarks on budgets or prior-year performance.

2.3.3 Problems with Performance Measures