3.7 The Stock Option Explosion (1992–2001)

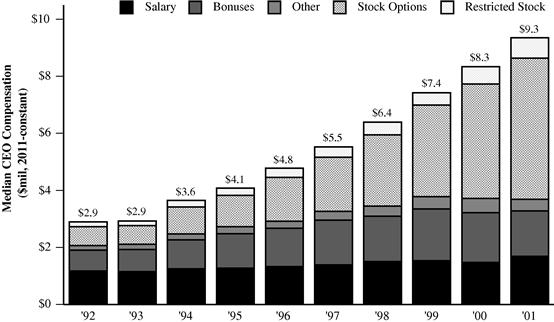

As shown in Figure 17 (and Figures 3 and 4), the median pay for CEOs in S&P 500 firms more than tripled between 1992 and 2001, driven by an explosion in the use of stock options. CEO incentive compensation in the early 1990s was split about evenly between options and accounting-based bonuses. By 1996, options had become the largest single component of CEO compensation in S&P 500 firms, and the use of options was even greater in smaller firms (and especially high-tech start-ups). By 2000, stock options accounted for more than half of total compensation for a typical S&P 500 CEO.

Figure 17 Median Grant-date Compensation for CEOs in S&P 500 Firms, 1992–2001. Note: Median pay levels (in 2011-constant dollars) based on ExecuComp data for S&P 500 CEOs. Total compensation (indicated by bar height) defined as the sum of salaries, non-equity incentives (including bonuses), benefits, stock options (valued on the date of grant using company fair-market valuations, when available, and otherwise using ExecuComps modified Black–Scholes approach), stock grants, and other compensation. Other compensation excludes pension-related expenses. Pay composition percentages defined as the average composition across executives.

The escalation of stock-option grants cannot be explained by a single factor. Instead, I believe that there are six main factors that fueled the explosion in stock options:

• Shareholder pressure for equity-based pay;

• Clinton’s $1 million deductibility cap;

• Accounting rules for options;

In this section, I will discuss each of these factors in rough chronological order (referring to prior discussions when appropriate), and indicate how they contributed to the option explosion.

3.7.1 Shareholder Pressure for Equity-Based Pay

As discussed in Section 3.6.2, the decline in takeover activity in the late 1980s corresponded to the rise in shareholder activism. This new breed of activists—including many of the largest state pension funds—demanded increased links between CEO pay and shareholder returns. The activists were joined by academics such as Jensen and Murphy (1990a), who famously (or infamously) argued “It’s not how much you pay, but how that matters.” Jensen and Murphy (1990b) showed that CEOs of large companies were paid like bureaucrats, in the sense that they were primarily paid for increasing the size of their organizations, received small rewards for superior performance, even smaller penalties for failures, and that the bonus components of the pay packages showed very little variability, less even then the variability of the pay of rank-and-file employees. They concluded that compensation committees and boards should focus primarily on the incentives provided by the pay package rather than the level of pay, and were joined by shareholder activists such as the United Shareholders Association in advocating more stock ownership and more extensive use of stock options.

Companies responded by taking Jensen and Murphy’s mantra a bit too literally: adding increasingly generous grants of stock options on top of already competitive pay packages, without any reduction in other forms of pay and showing little concern about the resulting inflation in pay levels.

3.7.2 SEC Holding–Period Rules

When an executive exercises a non-qualified stock option, the executive pays the exercise price and owes income tax on the gain. As discussed in Section 3.5.4, SEC rules in effect May 1991 required executives to hold shares acquired from exercising stock options for at least six months. The executive could defer the taxes during the six-month holding period (leading many executives to exercise after June 30, pushing the tax liability to the following year), but would still owe taxes on the gain on the exercise date even if stock prices fell over the subsequent six months. This rule implies that executives cannot finance the exercise by selling shares acquired in the exercise, and executives exercising stock options therefore faced both significant short-run cash-flow problems (from paying the exercise price) and increased risk.

Before May 1991, the SEC defined the exercise of an option as a “stock purchase” reportable by corporate insiders on Form 4 within 10 days following the month of the transaction. On May 1, 1991, in response to demands for more transparency of option grants, the SEC defined the acquisition rather than the exercise of the option as the reportable stock purchase. As a consequence of this change, the six-month holding period required by the Securities Act’s “short-swing profit” rule now begins when options are granted, and not when executives acquire shares upon exercise. Therefore, as long as the options are exercised more than six months after they are granted, the executive is free to sell shares immediately upon exercise. This ruling significantly increased the value of the option from the standpoint of the recipient.

3.7.3 The Clinton $1 Million Deductibility Cap

The controversy over CEO pay became a major political issue during the 1992 US presidential campaign.92 Bill Clinton promised to end the practice of allowing companies to take unlimited tax deductions for excessive executive pay; Dan Quayle warned that corporate boards should curtail some of the exorbitant salaries paid to corporate executives that were unrelated to productivity; Bob Kerry called it unacceptable for corporate executives to make millions of dollars while their companies were posting losses; Paul Tsongas argued that excessive pay was hurting America’s ability to compete in the international market; and Pat Buchanan argued “you can’t have executives running around making $4 million while their workers are being laid off.”

After the 1992 election, president-elect Clinton reiterated his promise to define compensation above $1 million as unreasonable, thereby disallowing deductions for all compensation above this level for all employees. Concerns about the loss of deductibility contributed to an unprecedented rush to exercise options before the end of the 1992 calendar year, as companies urged their employees to exercise their options while the company could still deduct the gain from the exercise as a compensation expense.93 In anticipation of the loss of deductibility, large investment banks accelerated their 1992 bonuses so that they would be paid in 1992 rather in 1993. In addition, several publicly traded Wall Street firms, including Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, and Bear Stearns, announced that they consider returning to a private partnership structure if Clinton’s plan were implemented.94

By February 1993, President Clinton backtracked on the idea of making all compensation above $1 million unreasonable and therefore non-deductible, suggesting that exemptions would be granted if the company could meet (not yet developed) federal standards proving that the executive improved the firm’s productivity.95 In April, details of the considerably softened plan began to emerge.96 As proposed by the Treasury Department and eventually approved by Congress as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, Section 162(m) of the tax code applies only to public firms and not to privately held firms, and applies only to compensation paid to the CEO and the four highest-paid executive officers as disclosed in annual proxy statements (compensation for all others in the firm is fully deductible, even if in excess of the million-dollar limit). More importantly, Section 162(m) does not apply to compensation considered performance-based for the CEO and the four highest-paid people in the firm.

Performance-based compensation, as defined under Section 162(m), includes commissions and pay based on the attainment of one or more performance goals, but only if (1) the goals are determined by an independent compensation committee consisting of two or more outside directors, and (2) the terms of the contract (including goals) are disclosed to shareholders and approved by shareholders before payment. Stock options generally qualify as performance based, but only if the exercise price is no lower than the market price on the date of grant. Base salaries, restricted stock vesting only with time, and options issued with an exercise price below the grant-date market price do not qualify as performance based.

Under the IRS definition, a bonus based on formula-driven objective performance measures is considered performance based (so long as the bonus plan has been approved by shareholders), while a discretionary bonus based on ex post subjective assessments is not considered performance based (because there are not predetermined performance goals). However, the tax law has been interpreted as allowing negative but not positive discretionary payments: the board can use its discretion to pay less but not more than the amount indicated by a shareholder-approved objective plan.

In enacting Section 162(m), Congress used (or abused) the tax system to target a small group of individuals (the five highest-paid executives in publicly traded firms) and to punish shareholders of companies who pay high salaries. Indeed, the stated objective of the proposal that evolved into Section 162(m) was not to increase tax revenues but rather to reduce the level of CEO pay. For example, the House Ways and Means Committee described the congressional intention behind the legislation:

Recently, the amount of compensation received by corporate executives has been the subject of scrutiny and criticism. The committee believes that excessive compensation will be reduced if the deduction for compensation (other than performance-based compensation) paid to the top executives of publicly held corporations is limited to $1 million per year.97

Ironically, although the objective of the new IRS Section 162(m) was to reduce excessive CEO pay levels by limiting deductibility, the ultimate result (similar to what happened in response to the golden parachute restrictions) was a significant increase in CEO pay. First, since compensation associated with stock options is generally considered performance-based and therefore deductible (as long as the exercise price is at or above the grant-date market price), Section 162(m) encouraged companies to grant more stock options. Second, while there is some evidence that companies paying base salaries in excess of $1 million lowered salaries to $1 million following the enactment of Section 162(m) (Perry and Zenner, 2001), many others raised salaries that were below $1 million to exactly $1 million (Rose and Wolfram, 2002). Finally, companies subject to Section 162(m) typically modified bonus plans by replacing sensible discretionary plans with overly generous formulas (Murphy and Oyer, 2004).

It is difficult to argue with the principle that companies should only be able to deduct compensation expenses for services rendered. However, the $1 million reasonableness standard is inherently arbitrary and has not been indexed for either inflation (+60% from 1993 to 2011) or changes in the market for executive talent: compensation plans that seemed excessive in 1993 are considered modest by current standards. More importantly, Section 162(m) disallows deductions for many value-increasing plan designs. For example, Section 162(m) disallows deductions for restricted stock or for options issued in the money, even when such grants are accompanied by an explicit reduction in base salaries. In addition, Section 162(m) disallows deductions for discretionary bonuses based on a board’s subjective assessment of value creation. I suspect that many compensation committees have welcomed the tax-related justification for not incorporating subjective assessments in executive reward systems. After all, no one likes receiving unfavorable performance evaluations, and few directors enjoy giving them. It is therefore not surprising that directors are often unwilling to devote the time, personal effort and courage to provide accurate, frank and effective performance appraisals of CEOs and other top executives. But, by failing to make the appraisals, directors are breaching one of their most important duties to the firm.

Moreover, Section 162(m) has distorted the information companies give to shareholders. In particular, in order to circumvent restrictions on discretionary bonuses, companies have created a formal shareholder-approved plan that qualifies under the IRS Section 162(m) while actually awarding bonuses under a different shadow plan that pays less than the maximum allowed under the shareholder-approved plan. These shadow plans often have little or nothing to do with the performance criteria specified in the shareholder-approved plans. As a consequence, the bonus plans and the performance metrics described in company proxy statements are not necessarily reflective of the actual formulas and performance measures used to determine bonuses.

Finally, it is worth noting that Section 162(m) is highly discriminatory, applying only to the compensation received by the top five executive officers, and applying only to publicly traded companies and not to private firms or partnerships. Ultimately, arbitrary and discriminatory tax rules such as Section 162(m) have increased the cost imposed on publicly traded corporations and have made going-private conversions more attractive.

3.7.4 There’s (Still) No Accounting for Options

The 1972 APB Opinion 25—which defined the accounting treatment for stock options as the spread between the market and exercise price on the grant-date—pre-dated Black and Scholes (1973), which offered the first formula for computing the value of a traded call option. Academic research in option valuation exploded over the next decade, and financial economists and accountants became increasingly intrigued with using these new methodologies to value, and account for, options issued to corporate executives and employees.

In 1984, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) floated the idea that companies account for employee stock options using the so-called minimum value approach.98 By June 1986, the FASB idea had evolved into a proposal with the important change that the accounting charge would be based on the fair market value (e.g. the Black–Scholes value) and not a minimum value. The proposal was vehemently opposed by all of the Big Eight accounting firms, the American Electronics Association (including more than 2800 corporate members), the Financial Executives Institute, the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, and the National Venture Capital Association.99 Many of the criticisms focused on the complexity of the Black–Scholes formula, as exemplified by the following quote from Joseph E. Connor, chairman of Price Waterhouse:

Corporate America rightfully is skeptical of any standard that depends upon complex pricing models that provide partial and debatable answers. Yet after two years of fruitless efforts, the FASB persists in trying to turn this ivory-tower notion into a usable standard. The compensation element is a mirage, tempting to the imagination but impossible to touch. The board should turn its attention to more productive areas.100

Ultimately, and without fanfare, FASB tabled its 1986 proposal before submitting an exposure draft.

In late 1991, Senator Carl Levin (D-Michigan) attempted to bypass FASB by introducing the Corporate Pay Responsibility Act requiring companies to take a charge to their earnings to reflect the cost of option compensation packages; as noted in Section 3.6.3, the bill also directed the SEC to require more disclosure for stock option arrangements in company proxy statements. Although Levin’s bill was ultimately shelved, it provided pressure for renewed FASB focus on option expensing.

In April 1992, FASB voted 7-0 to endorse an accounting charge for options, and issued a formal proposal in 1993. The proposal created a storm of criticism among business executives, high-tech companies, accountants, compensation consultants, the Secretary of the Treasury, and shareholder groups.101 In March 1994, more than 4000 employees from 150 Silicon Valley firms rallied against the accounting change, calling on the Clinton Administration to block the proposal because it would restrict job creation and economic growth. Even President Clinton, usually a critic of high executive pay, waded into the debate by expressing that it would be unfortunate if FASB’s proposal inadvertently undermined the competitiveness of some of America’s most-promising high-tech companies.102 In the aftermath of the overwhelmingly negative response, FASB announced it was delaying the proposed accounting change by at least a year, and in December 1994 it dropped the proposal.

In 1995, FASB issued a compromise rule, FAS 123, which recommended but did not require that companies expense the fair-market value of options granted (using Black–Scholes or a similar valuation methodology). However, while FASB allowed firms to continue reporting under APB Opinion 25, it imposed the additional requirement that the value of the option grant would be disclosed in a footnote to the financial statements. Predictably, only a handful of companies adopted FASB’s recommended approach. As I will discuss below in Section 3.8.4, it wasn’t until the accounting scandals in the early 2000s that a large number of firms voluntarily began to expense their option grants.

The accounting treatment of options promulgated the mistaken belief that options could be granted without any cost to the company. This view was wrong, of course, because the opportunity or economic cost of granting an option is the amount the company could have received if it sold the option in an open market instead of giving it to employees. Nonetheless, the idea that options were free (or at least cheap) was erroneously accepted in too many boardrooms. Options were particularly attractive in cash-poor start-ups (such as in the emerging new economy firms in the early 1990s), which could compensate employees through options without spending any cash. Indeed, providing compensation through options allowed the companies to generate cash, since when options were exercised, the company received the exercise price and could also deduct the difference between the market price and exercise price from its corporate taxes. The difference between the accounting and tax treatment gave option-granting companies the best of both worlds: no accounting expense on the company’s books, but a large deduction for tax purposes. When coupled with the May 1991 rule eliminating holding requirements after exercise, stock options had important perceived advantages over all other forms of compensation.

As both an illustration of how accounting affects compensation decisions, and as an interesting episode in its own right, consider how a change in accounting rules affected option repricing. On December 4, 1998, FASB announced that repriced options issued on or after December 15, 1998 would be treated under “variable accounting”, meaning that the company would take an accounting charge each year for the repriced option based on the actual appreciation in the value of the option. FASB issued its final rule in March 2000 as FASB Interpretation No. 44, or FIN 44, indicating that FASB did not consider this a new rule but rather a re-interpretation of an old rule. In particular, FASB reasoned that the “fixed accounting” under APB Opinion 25 (in which the option expense was equal to the spread between the market and exercise price on the first date when both the number of options granted and the exercise price become known or fixed) did not apply to companies that have a policy of revising the exercise price.

Companies with underwater options rushed to reprice those options in the 12-day window between December 4–15, 1998.103 Indeed, Carter and Lynch (2003) document a dramatic increase in repricing activities during the short window, followed by dramatic declines; Murphy (2003) shows that repricings virtually disappeared after the accounting charge. Many companies with declining stock prices circumvented the accounting charge on repriced options by canceling existing options and re-issuing an equal number of options after waiting six months or more. But this replacement is not neutral. It imposes substantial risk on risk-averse employees since the exercise price is not known for six months and can conceivably be above the original exercise price. In addition, canceling and reissuing stock options in this way provides perverse incentives to keep the stock-price down for six months so that the new options will have a low exercise price. All of this scrambling to avoid an accounting charge!

3.7.5 SEC Option Disclosure Rules

The most widely debated issue surrounding the SEC’s 1992 disclosure rules was how stock options would be valued in both the Summary Compensation Table and in the Option Grant table. The SEC wanted a total dollar cost of option grants so that the components in the Summary Compensation Table could be added together to yield a value for total compensation, and lobbied for calculating option cost using a Black and Scholes (1973) or related approach. The SEC’s proposal was vehemently opposed by high option-granting firms (especially from the Silicon Valley and Boston’s 128 corridor) and (more surprisingly) by compensation consulting and accounting firms. Ultimately, a compromise was struck: the Summary Compensation Table would include the number, but not the cost, of options granted, thus defeating the SEC’s objective of reporting a single number for total compensation. In addition, companies would have a choice in the Option Grant Table to report either the Black–Scholes grant-date cost or the potential cost of options granted (under the assumption that stock prices grow at 5% or 10% annually during the term of the option).104

From the perspective of many boards and top executives who perceive options to be nearly costless, or indeed deny that options have value when granted, the only way they can quantify the options they award is by the number of options granted. The focus on the quantity rather than the cost of options is further solidified by the SEC’s 1992 disclosure rule and also by institutions that monitor option plans. For example, under the current listing requirements of the New York Stock Exchange and the National Association of Security Dealers (NASD), companies must obtain shareholder approval for the total number of options available to be granted, but not for the cost of options to be granted. Advisory firms (such as Institutional Shareholder Services) often base their shareholder voting recommendations on the option “overhang” (that is, the number of options granted plus options remaining to be granted as a percent of total shares outstanding), and not on the opportunity cost of the proposed plan. Therefore, boards and top executives often implicitly admit that the number of options granted imposes a cost on the company, while at the same time denying that these options have any real dollar cost to the company.

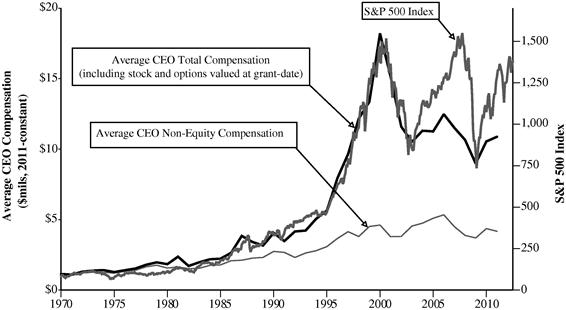

The focus on the quantity rather than the cost of options granted helps explain a puzzling result in the executive pay literature (e.g. Hall and Murphy, 2003): the near-perfect correlation between the S&P 500 Index and average grant-date CEO pay. Figure 18 depicts the correlation between the S&P 500 Index and average CEO pay between 1970 and 2011. As shown in the figure, while “non-equity compensation” is at most weakly related to the performance of the overall stock market, total compensation was almost perfectly correlated until 2003, when the “bull market” from 2003-2007 was associated with relatively modest increases in average CEO pay.

Figure 18 Grant-Date Pay for CEOs in S&P 500 Firms vs. S&P 500 Index, 1970–2011. Note: The S&P 500 Index is a capitalization-weighted index of the prices of 500 large-cap common US stocks; the figure depicts monthly values. Compensation data are based on all CEOs included in the S&P 500, using data from Forbes and ExecuComp. CEO total pay includes cash pay, restricted stock, payouts from long-term pay programs and the value of stock options granted (using company fair-market valuations, when available, and otherwise using ExecuComp’s modified Black–Scholes approach). Equity compensation prior to 1978 estimated based on option compensation in 73 large manufacturing firms (based on Murphy (1985)), equity compensation from 1979 through 1991 estimated as amounts realized from exercising stock options during the year, rather than grant-date values. Non-equity incentive pay is based on actual payouts rather than targets. Dollar amounts are converted to 2011-constant dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

We would expect realized compensation to vary with the overall market, since the gains from exercising non-indexed stock options will naturally increase with the market. But the compensation data in Figure 18 are based on the grant-date cost of the options, and not the amounts realized from exercising options. If compensation committees focused on the grant-date cost of options, we would expect the number of options granted to decrease when share prices increase, and would expect no systematic correlation between the average pay and average market returns. However, if compensation committees focused on the number of options (e.g. granting the same number of options each year, as opposed to the same “value” of options each year), we would obtain the pattern in Figure 18. Because the grant-date Black–Scholes cost of an option is approximately proportional to the level of the stock price, awarding the same number of options after a doubling of stock prices amounts to doubling the cost of the option award. Therefore, if the number of options granted stayed constant over time, the cost of the annual option grants would have risen and fallen in proportion to the changes in stock prices.

If my interpretation of the data is correct, then the focus on the quantity (rather than cost) of options changed around 2002–2003. As I will argue below in Section 3.8.4, companies began voluntarily expensing the cost of options in 2002, both in response to the recent accounting scandals and in anticipation of mandated expensing in 2006. In addition, in 2006 the SEC changed its disclosure rules to require option costs (rather than the number of options) in the Summary Compensation Table.

3.7.6 New York Stock Exchange Listing Requirements

Another contributing factor to the explosion in stock options—both to top executives and lower-level employees—was a 1998 change or “clarification” to New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) listing requirements. Under listing rules in affect at the time, companies needed shareholder approval for equity plans covering top-level executives, but did not need approval for broad-based plans. While the SEC had not been clear on how “broad-based” was defined, the general understanding was that such plans involved equity or option grants to employees below the executive level.

In January 1998, the NYSE quietly filed with the SEC a proposal clarifying definition of a “broad-based” plan as any plan in which (1) at least 20% of the company’s employees were eligible to participate, and (2) at least half of the eligible employees were neither officers nor directors. The definition was a “safe harbor” (i.e. sufficient but not necessary): plans meeting the two criteria were presumed to be broadly based (and therefore could be introduced without shareholder approval), while plans falling outside these parameters would be considered on a case-by-case basis. The SEC received no letters questioning the proposed rule during the “public comment” period, and the ruling was approved and took effect on April 8, 1998. The final ruling was a surprise to shareholder advocates and institutions, who admitted to being embarrassed to have missed the proposal filing, and furious that it had been “buried” in the federal register and listed as a “cryptic notice” on the SEC’s website.105 Many observers speculated that the new rule was designed to lure NASDAQ companies to the NYSE, and most feared it would “open the floodgates” for executive stock options, since companies could avoid a shareholder vote by rolling their management plans into new broader-based plans. Consistent with my conclusions in Section 3.7.5, shareholder criticism focused exclusively on the dilutive effect of the option plans, on not on the transfer of value from shareholders to employees.

The NYSE—facing a barrage of criticism over its new rule—reopened the comment period (this time receiving 166) and created a task force to consider the new comments and make further suggestions. In June 1999, based on the recommendations of the task force, the NYSE issued “interim” new rules. Under the revised rules, the majority of the firm’s non-exempt (e.g. non-managerial) employees (rather than 20% of all employees) must be eligible to participate, and the majority of options granted must go to non-officers (rather than the majority of the participants being non-officers). The new rule was an “exclusive test” rather than a safe harbor.

The new rules were enacted as companies faced growing political pressure to push grants to managers and employees at lower levels in the organization.106 Several bills that encouraged broad-based stock option plans were introduced in Congress, including the Employee Stock Option Bill of 1997 (H.R. 2788) to ease the restrictions on qualified Incentive Stock Options granted to rank-and-file workers. At the same time, employees clamored for broad-based grants, but only if the company would promise that other components of their compensation would not be lowered. As a result of these pressures, the number and cost of options granted grew substantially.

Figure 19 shows the average annual option grants as a fraction of total common shares outstanding. In 1992, the average S&P 500 company granted its employees options on about 1.1% of its outstanding shares. In 2001, in spite of the bull market that increased share prices (that, in turn, increased the value of each granted option), the average S&P 500 company granted options to its executives and employees on 2.6% of its shares. By 2005, annual grants as a fraction of outstanding shares fell below 1995 levels to 1.3%.

Figure 19 Grant-Date Number of Employee Stock Options (measured by % of company shares) in the S&P 500, 1992–2005. Note: Figure shows the grant-date number of options as a percent of total common shares outstanding granted to all employees in an average S&P 500 firm, based on data from S&Ps ExecuComp database. Grants below the Top 5 executives are estimated based on Percent of Total Grant disclosures. Companies not granting options to any of their top five executives are excluded.

Figure 20 shows the average inflation-adjusted grant-date values of options awarded by the average firm in the S&P 500 from 1992-2005.107 Over this decade, the value of options granted increased from an average of $27 million per company in 1992 to nearly $300 million per company in 2000, falling to $88 million per company in 2005. Ignored in the news coverage and controversy over stock options awarded to CEOs and the next four highest-paid executives is the fact that employees and executives ranked below the top five have received between 85% and 90% of the total option awards.

Figure 20 Grant-Date Values of Employee Stock Options in the S&P 500, 1992–2005. Note: Figure shows the grant-date value of options (in millions of 2011-constant dollars) granted to all employees in an average S&P 500 firm, based on data from S&Ps ExecuComp data. Grants below the Top 5 are estimated based on Percent of Total Grant disclosures; companies not granting options to any of their top five executives are excluded. Grant-values are based on company fair-market valuations, when available, and otherwise use ExecuComps modified Black–Scholes approach.

Over the 14-year 1992–2005 time period, the average S&P 500 company awarded nearly $1.6 billion worth of options to its executives and employees (or nearly $800 billion across all 500 companies). What is generally unappreciated is that in this process the average S&P 500 company transferred through options approximately 25.6% of its total outstanding equity to its executives and employees.108

Broad-based option grants were particularly generous in “new economy” firms and in firms below the S&P 500. Hall and Murphy (2003) show that the average new-economy firm in the S&P 500, S&P MidCap 400 and S&P SmallCap 600 granted options on 5.8% of its stock annually to employees below the top five between 1993 and 2001 (compared to only 2.3% annually in “old economy” firms). In 2000 alone, the average employee (below the top five) in the new-economy sector received options with a Black–Scholes value of $32000.109

The backlash against the explosion in option grants grew following the 2000 burst in the Internet bubble, when companies granted even more options at a lower price so that employees were not penalized for poor performance. Shareholder activists concerned about dilution pressured the NYSE to reconsider their rules. In late 2002, the NYSE and NASDAQ passed uniform new rules requiring shareholder approval for all equity plans, with no exemption for broad-based plans. The new rules—which also required shareholder approval for option repricings—were approved by the SEC and went into effect in July 2003.

3.8 The Accounting and Backdating Scandals (2001–2007)

3.8.1 Accounting Scandals and Sarbanes-Oxley

Accounting scandals erupted across corporate America during the early 2000s, destroying the reputations of once-proud firms such as Enron, WorldCom, Qwest, Global Crossing, HealthSouth, Cendant, Rite-Aid, Lucent, Xerox, Tyco International, Adelphia, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Arthur Andersen. In the midst of these scandals, Congress quickly passed the sweeping Sarbanes-Oxley Act in July 2002, setting or expanding standards for accounting firms, auditors, and boards of directors of publicly traded companies. The Act was primarily focused on accounting irregularities and not on compensation. However, Congress could not resist the temptation to use the new law to further regulate executive pay.

First, in direct response to the forgiveness of certain corporate loans given to executives at Tyco International, Section 402 of Sarbanes-Oxley prohibited all personal loans to executives and directors, regardless of whether such loans served a useful and legitimate business purpose. For example, prior to Sarbanes-Oxley, companies would routinely offer loans to executives to buy company stock, often on a non-recourse basis so that the executive could fulfill the loan obligations by returning the purchased shares.110 Similarly, companies attracting executives would routinely offer housing subsidies in the form of forgivable loans, a practice made unlawful under the new regulations.111 Finally, Sarbanes-Oxley is viewed as prohibiting company-maintained cashless exercise programs for stock options, where an executive exercising options can use some of the shares acquired to finance both the exercise price and income taxes due upon exercise.112

Second, Section 304 of Sarbanes-Oxley requires CEOs and CFOs to reimburse the company for any bonus or equity-based compensation received, and any profits realized from selling shares, in the twelve months commencing with the filing of financial statements that are subsequently restated as a result of corporate misconduct. This “clawback” provision of Sarbanes-Oxley—which was subsequently extended in the TARP legislation and Dodd–Frank Financial Reform Act discussed below—was notable mostly for its ineffectiveness. Indeed, in spite of the wave of accounting restatements that led to the initial passage of Sarbanes-Oxley, the first individual clawback settlement under Section 304 did not occur until more than five years later, when UnitedHealth Group’s former CEO William McGuire was forced to return $600 million in compensation.113 The SEC became more aggressive in 2009, launching two clawback cases (CSK Auto and Diebold, Inc.) where the targeted executives were not accused of personal wrongdoing.114

Finally, Section 403 of Sarbanes-Oxley required that executives disclose new grants of stock options within two business days of the grant; before the Act options were not disclosed until 10 days after the end of the month when the option was granted. As discussed in the next section, this provision had the unintended but ultimately beneficial effect of curbing option backdating for top executives more than two years before the existence of backdating was discovered.

3.8.2 Option Backdating

In 2005, academic research by University of Iowa professor Erik Lie and subsequent investigations by the Wall Street Journal unearthed a practice that became known as option backdating.115 Under this practice, companies deliberately falsified stock option agreements so that options granted on one date were reported as if granted on an earlier date when the stock price was unusually low—commonly the lowest price in the quarter or in the year. Thus, options that were reported as granted at the money (that is, with an exercise price equal to the market price on the reported grant-date) were in reality granted in the money (that is, with an exercise price well below the market price on the actual grant-date). This unsavory practice violates federal disclosure rules, accounting and tax laws, and often violated the company’s own stock-option policies, as follows:

• Under SEC rules in effect since 1993, companies granting options with an exercise price different from the fair market price on the grant-date are required to disclose this information to shareholders. Thus, companies backdating options should have informed shareholders that the options were actually issued with an exercise price less than the fair market value on the actual grant-date.

• As discussed in Sections 3.5.3 and 3.7.4, under FASB rules in effect before 2006, companies would typically face an accounting charge for stock options only if the exercise price was set lower than the grant-date market price. Thus, companies that backdated options reported no accounting expense when the actual accounting expense should have been the spread between the market and exercise price (amortized over the vesting period of the option). Companies backdating options are therefore not only falsifying option agreements, they are committing accounting fraud.

• As discussed in Section 3.7.3, compensation for proxy-named executives in excess of $1 million is deductible only if the compensation is performance based under the definition of IRS Section 162(m). In order for payments related to stock options to be considered performance based, the options must meet several criteria including having an exercise price that is at least as high as the grant-date market price.116 Thus, assuming that the affected executives are subject to the $1 million threshold, companies that backdated options are taking deductions for compensation that is not deductible.

• Finally, most shareholder-approved stock option agreements include provisions specifying that option exercise prices must be no less than 100% of the market price on the date of grant. Thus, companies with such provisions that backdate options are violating their own internal policies.

The Wall Street Journal’s crusade against backdating triggered SEC investigations into more than 140 firms. By August 2009, the SEC had filed civil charges against 24 companies and 66 individuals for backdating-related offenses, and at least 15 people had been convicted of criminal conduct.117 In May 2007, Comverse Technology’s former general counsel, William Sorin, pleaded guilty to a conspiracy charge and became the first corporate executive sent to prison for backdating executive and employee stock options; his boss (Comverse’s founder and former CEO Kobi Alexander) fled to Namibia and is fighting extradition while remaining on the FBI’s most wanted list.118 In January 2008, Brocade’s former CEO, Gregory Reyes, became the first executive to go to trial and be convicted on backdating charges; Reyes was sentenced to 21 months in prison and ordered to pay a $15 million fine. Brocade’s former human resource executive was also convicted.119 Reyes’ conviction was thrown out by the US Court of Appeals in 2009, citing prosecutorial misconduct, but he was retried, reconvicted, and resentenced to 18 months in prison in June 2010.120 In addition to the SEC civil and criminal charges, scores of companies have restated their financials based on internal investigations into backdating, and many have settled class action or derivative suits brought by shareholders.

Some backdating cases were obvious in retrospect, such as Cablevision’s award of backdated options to its vice chairman after his death in 1999.121 In most cases, however, executives would often go to considerable lengths to hide the backdating practices from the company’s auditors, shareholders, and tax authorities. For example, in its investigation of backdating at Sycamore Networks, the SEC uncovered an internal menu that discussed ways to alter employees hire dates so they could get options with lower exercise prices, and also evaluated the risk that the changes might be discovered by auditors.122 Executives at Mercury Interactive used WhiteOut to alter the dates on option documents, and joked about magic backdating ink.123

As noted above in Section 3.8.1, changes in reporting requirements in 2002 essentially put an end to option backdating for top-level executives more than two years before academics and the media uncovered the practice. Between May 1992 and August 2002, option grants for corporate insiders were typically not disclosed until 10 days after the end of the month when the option was granted, providing substantial opportunity for manipulating grant-dates. In August 2002, as part of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, the SEC required executives receiving options to disclose those grants within two business days after the grant was made. Heron and Lie (2006a) and Narayanan and Seyhun (2005) show that the abnormal run-up in stock prices following reported grant-dates (which they interpret as evidence of backdating) declined substantially after the new reporting rules, thus suggesting that the Sarbanes-Oxley Act had the unintended (but desirable) effect of stemming backdating practices.124

By 2010, the SEC’s investigations and prosecutions of backdating had wound down. New disclosure rules introduced in 2006 were designed to identify new backdating cases by requiring companies to report not only exercise prices for option grants, but also the grant-date market price, date of grant, and the date that the board approved the grant.125 While there is no accepted count of the number of companies engaged in backdating (beyond the 24 companies formally charged by the SEC or the approximately 150 companies that have restated financials after internal investigations revealed backdating126), academic research has suggested that the practice was widespread. Based on statistical analysis of exercise prices, Edelson and Whisenant (2009) estimate that as many as 800 firms engaged in the practice; other estimates have been as high as 2000.127

In retrospect, while issuing options with exercise prices below grant-date market prices can be part of an efficient compensation structure, it is difficult to defend the practice of backdating and the ex post manipulation and falsification of grant-dates. However, it is also difficult to defend the SEC’s aggressiveness in prosecuting and criminalizing what would seem to be relatively minor books and records infractions. Consider the following:

• There is nothing illegal about setting exercise prices to the lowest price observed during a month or quarter (or any other price), as long as the company appropriately discloses the practice and (based on FASB rules in effect before 2006) records an accounting expense equal to the difference between the exercise price and the market price on the true grant-date. In practice, however, very few firms issue options with exercise prices below market prices precisely because of the accounting charge associated with such options.

• Companies charged with backdating have restated their financials to reflect the actual spread between the exercise and market price. However, this remedy misses the point: the relevant alternative to backdating was not issuing in-the-money options and taking an accounting charge, but rather issuing a larger number of at-the-money options and avoiding the accounting charge. Therefore, under this relevant alternative, there would be no change in reported accounting expenses or earnings, but there would be an increase in the number of options granted.

• There is no evidence to my knowledge that companies engaged in backdating systematically overpaid lower-level employees receiving such grants, thus no evidence that backdating was associated with a large transfer of wealth from shareholders to employees.128

The SEC prosecuted backdating cases with a zeal usually reserved for hardened criminals. Executives associated with backdating schemes were charged with myriad crimes, including filing false documents, securities fraud, and conspiracy to commit securities fraud. KB Homes former CEO Bruce Karatz, for example, faced up to 415 years in prison if convicted on all backdating-related charges including 15 counts of mail, wire, and securities fraud, four counts of making false statements in SEC filings, and one count of lying to his company’s accountants. Mr. Karatz was ultimately convicted in April 2010 on two counts of mail fraud, one count each of making false statements in SEC filings and to his accountants and faced up to 80 years in prison.129 Ultimately, however, Mr. Karatz was sentenced to five years probation (including eight months of house arrest), a $1 million fine and 2,000 hours of community service.

The SEC’s record of successful convictions has been far from perfect. Its suit against Michael Shanahan for backdating at Engineered Support Systems was dismissed midtrial when the judge determined that the SEC’s case provided no evidence of fraud. Similarly, the SEC’s high-profile case against Broadcom was dismissed amid claims of significant prosecutorial misconduct and lack of criminal intent.130

3.8.3 Enron and Section 409(A)

Enron, like many other large companies, allowed mid-level and senior executives to defer portions of their salaries and bonuses through the company’s non-qualified deferred compensation program. When Enron filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in December 2002, about 400 senior and former executives became unsecured creditors of the corporation, eventually losing most (if not all) of the money in their accounts.131 However, just before the bankruptcy filing, Enron allowed a small number of executives to withdraw millions of dollars from their deferred compensation accounts. The disclosure of these payments generated significant outrage (and law suits) from Enron employees who lost their money, and attracted the ire of Congress.

As a direct response to the Enron situation, Section 409(A) was added to the Internal Revenue Code as part of the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004. In essence, the objectives of Section 409(A) were to limit the flexibility in the timing of elections to defer compensation in nonqualified deferred compensation programs, to restrict withdrawals from the deferred accounts to pre-determined dates (and to prohibit the acceleration of withdrawals), and to prevent executives from receiving severance-related deferred compensation until six months after severance. Section 409(A) imposes taxes on individuals with deferred compensation as soon as the amounts payable under the plan are no longer subject to a substantial risk of forfeiture. Individuals failing to pay taxes in the year the amounts are deemed to no longer be subject to the substantial forfeiture risk owe a 20% excise tax and interest penalties on the amount payable (even if the individual has not received or may never receive any of the income).

One of the notable features of Section 409(A) is that it significantly broadens the definition of deferred compensation. For example, annual bonuses or reimbursement of expenses paid more than two and a half months after the close of the fiscal year are considered deferred compensation subject to Section 409(A). Similarly, supplemental executive retirement plans (SERPs), phantom stock awards, stock appreciation rights, split-dollar life insurance arrangements, and individual employment agreements allowing deferral of compensation or severance awards are also (under some circumstances) considered deferred compensation subject to Section 409(A).

While developed as a response to the Enron situation, Section 409(A) was still being drafted when the option backdating scandals came to light. As a result, Congress defined discount options (i.e. options with an exercise price below the market price on the date of grant) as deferred compensation subject to Section 409(A). In particular, Section 409(A) requires discount options to have a fixed exercise date (that is, a date in the future when the option must be exercised). Unless the option holder pre-commits to the future date when the option will be exercised, the holder is subject to a 20% penalty tax, in additional to regular income tax, plus possible interest and other penalties, regardless of whether the option is ever exercised.132 The new rule applied retroactively to options granted before 2005 but not vested as of December 31, 2004, and was explicitly designed to penalize senior executives receiving backdated options.

3.8.4 Accounting for Options (Finally!) and the Rise of Restricted Stock

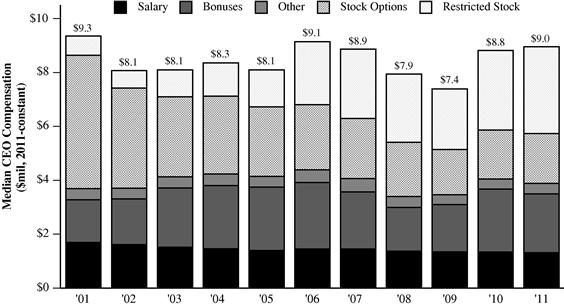

The first decade of the new century have brought several important changes in the level and composition of CEO pay. As shown in Figure 21, median grant-date total CEO pay in the S&P 500 declined from $9.3 million in the peak year of 2001 to $9.0 million in 2011, representing the first prolonged stagnation in CEO pay since the early 1970s. The decrease in pay primarily reflects both a substantial decline in the grant-date value of stock options, and a shift in the industry composition of the S&P 500. In 2001, the value of stock options at the award date accounted for 53 percent of the pay for the typical S&P 500 CEO. By 2011, options accounted for only 21 percent of total pay. Moreover, the decline in stock option grants in the early 2000s has been associated with an increase in stock grants, which accounted for 36% of average pay by 2011 (up from only 8% in 2001). The stock grants include a mixture of traditional restricted stock (vesting only with the passage of time) and performance shares (where vesting is based on performance criteria).

Figure 21 Median Grant-date Compensation for CEOs in S&P 500 Firms, 2001–2011. Note: Median pay levels (in 2011-constant dollars) based on ExecuComp data for S&P 500 CEOs. Total compensation (indicated by bar height) defined as the sum of salaries, non-equity incentives (including bonuses), benefits, stock options (valued on the date of grant using company fair-market valuations, when available, and otherwise using ExecuComps modified Black–Scholes approach), stock grants, and other compensation. Other compensation excludes pension-related expenses. Pay composition percentages defined as the average composition across executives.

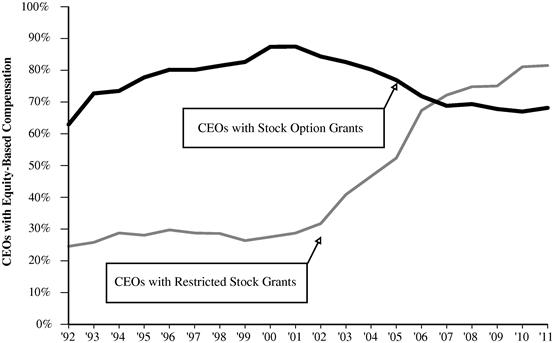

Figure 22 shows the percentage of S&P 500 companies that made stock option or restricted stock grants to their CEOs between 1992 and 2011. The percentage of companies granting options to their CEOs in each year increased from about 63% in 1992 to 87% by 2001, falling to 68% in 2011. Over the same time period, the percentage of companies making restricted stock or performance-share grants more than tripled from 25% to 82%. The trend suggests a substitution of stock grants for stock options, although more than half of the S&P 500 CEOs have received both options and restricted stock annually since 2006.

Figure 22 CEOs in S&P 500 Firms receiving equity-based compensation, 1992–2011. Note: Sample is based on all CEOs included in the S&P 500, based on S&P’s ExecuComp database. Stock grants include both restricted and performance shares.

One obvious explanation for the drop in stock options and the rise in restricted stock since the early 2000s is the stock market crash associated with the burst of the Internet Bubble in 2000 and exacerbated by the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in 2001. In particular, the sharp market-wide decline in stock prices in the early 2000s left many outstanding options underwater and lowered executive expectations for the future increases in their company’s stock prices. Indeed, in many cases, including Microsoft and Cablevision, current outstanding (but out-of-the-money) options were cancelled and replaced with restricted stock, often at terms very favorable to executives. Executives will naturally prefer restricted stock to options when they have low expectations for future firm performance. While restricted stock will always retain some value as long as the firm is valued at greater than its liabilities, executives often expect that options granted in a declining market are likely to expire worthless.

Indeed, stock options have always become more popular when stock markets are trending upward (i.e. bull markets) and less popular when markets trend down (i.e. bear markets). As documented throughout this history of CEO pay, almost every recession over the past 60 years has been associated with a reduced use of stock options, and during the lackluster 1970s many firms replaced their option plans with new accounting-based bonus plans designed to provide more predictable payouts. However, the spike in the importance of restricted shares in 2006 (rising in Figure 21 from 17% to 26% of total pay from 2005) in a year with robust stock-market performance (the Dow Jones increased by 16% in 2006) suggests that the decline in stock options in favor of restricted shares reflects more than market trends. I believe the answer largely reflects changes in the accounting treatment of options.

The scandals that erupted across corporate America during the early 2000s focused attention on the quality of accounting disclosures, which in turn renewed pressures for companies to report the expense associated with stock options on their accounting statements. Before 2002, only a handful of companies had elected to expense options under FAS123; the remainder elected to account for options under the old rules (where there was typically no expense). In the summer of 2002, several dozen firms announced their intention to expense options voluntarily; more than 150 firms had elected to expense options by early 2003 (Aboody, Barth, and Kasznik, 2004). Moreover, shareholder groups (most often representing union pension funds) began demanding shareholder votes on whether options should be expensed; more than 150 shareholder proposals on option expensing were submitted during the 2003 and 2004 proxy season (Ferri and Sandino, 2009). By late 2004, about 750 companies had voluntarily adopted or announced their intention to expense options. In December 2004, FASB announced FAS123R which revised FAS123 by requiring all US firms to recognize an accounting expense when granting stock options, effective for fiscal years beginning after June 15, 2005.

In addition to requiring an accounting expense for all options granted after June 15, 2005, FAS123R required firms to record an expense for options granted before this date that were not yet vested (or exercisable) as of this date. To avoid taking an accounting charge for these outstanding options, many firms accelerated vesting of existing options so that all options were exercisable by June 15, 2005 (Choudhary et al., 2009).

Under the accounting rules in place since 1972 (and continuing under FAS123R), companies granting traditional restricted stock (vesting only with the passage of time) recognize an accounting expense equal to the grant-date value of the shares amortized over the vesting period. Under FAS123R, the expense for stock options is similar to that of shares of stock: companies must recognize an accounting expense equal to the grant-date value of the options amortized over the period when the option is not exercisable. Option expensing (whether voluntarily under FAS123, or by law under FAS123R) significantly leveled the playing field between stock and options from an accounting perspective. As a result, companies reduced the number of options granted to top executives (and other employees), and greatly expanded the use of restricted shares.

The new accounting rules also facilitated another change long desired by shareholder advocates: a switch from traditional time-lapse restricted stock to “performance shares” that vest only upon achievement of accounting- or market-based performance goals. Angelis and Grinstein (2011), for example, report that 52% of the 2007 restricted stock awards for CEOs in the S&P 500 were performance-based.

Under the 1972 rules, performance shares were expensed using “variable” rather than “fixed” accounting, meaning that the company would record an expense based on the grant-date stock price, and then record additional expenses reflecting the appreciation or depreciation of the performance share up until the date that the performance hurdle was achieved. Therefore, if the stock price increased between the grant and the achievement of the performance hurdle (which is typically the case), the accounting expense for performance shares was higher than the accounting expense for traditional time-lapse restricted stock. In contrast, under FAS123R fair-market-value accounting, the expense for performance shares is generally less than the expense for traditional restricted stock, because the company can take into account the severity of the performance hurdles when estimating the fair-market value. In addition, while traditional restricted stock is considered non-performance-related under IRS Section 162(m) (and thus subject to the $1 million deductibility cap), performance shares can be structured to be fully deductible.

3.8.5 Conflicted Consultants and CEO Pay133

Most large companies rely on executive compensation consultants to make recommendations on appropriate pay levels, to design and implement short-term and long-term incentive arrangements, and to provide survey and competitive-benchmarking information on industry and market pay practices. In addition, consultants are routinely asked to opine on existing compensation arrangements and to give general guidance on change-in-control and employment agreements, as well as on complex and evolving accounting, tax, and regulatory issues related to executive pay.

Critics seeking explanations for high executive pay have increasingly accused these consultants as being (partly) to blame for the perceived excesses in pay. Concerns over the role of consultants led the SEC – as part of their 2006 overhaul of proxy disclosure rules – to require companies to identify any consultants who provided advice on executive or director compensation; to indicate whether or not the consultants are appointed by the companies’ compensation committees; and to describe the nature of the assignments for which the consultants are engaged.

Initial results from the 2007 proxy season appeared to buttress the concerns of the critics. An October 2007 report issued by the Corporate Library, “The Effect of Compensation Consultants” (Higgins, 2007) concluded that companies using consultants offer significantly higher pay than companies not using consultants.134 However, the cross-sectional correlation between CEO pay and the use of consultants does not imply that the consultants caused the high pay; it is equally plausible that companies with high pay are most likely to seek the advice of consultants. Indeed, Armstrong, Ittner, and Larcker (2012) find no evidence of differences in pay between a sample of firms using consultants and a matched sample of firms not using consultants. Similarly, based on a time-series of 2006-2009 data, Murphy and Sandino (2012) find no evidence that firms increase pay after retaining consultants.

The SEC’s disclosure requirements were followed by Congressional hearings and a December 2007 report from the US House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, “Executive Pay: Conflicts of Interest Among Compensation Consultants” (Waxman, 2007). The Congressional hearings focused on consultants offering a full range of compensation, benefits, actuarial and other human resources services in addition to executive pay. The provision of these other services creates a potential conflict of interest because the decisions to engage the consulting firm in these more-lucrative corporate-wide consulting areas are often made or influenced by the same top executives who are benefited or harmed by the consultant’s executive pay recommendations.

In response to the Congressional concerns, the SEC expanded its disclosure rules in 2009 to require firms to disclose fees paid to their executive compensation consultants whenever the consultants received more than $120,000 for providing any other services to the firm beyond those related to executive and director pay. The SEC exempted from these requirements firms that retain at least one compensation consultant that works exclusively for the board, and also exempted disclosing consultants that affect executives’ and directors’ compensation only through providing advice related to broad-based plans that do not discriminate executives and/or directors from other employees. As discussed below in Section 3.10.2, the SEC disclosure rules were further expanded in 2012 (as part of the implementation of the Dodd–Frank Act) to require firms to disclose whether the work of the consultant has raised any conflict if interest and, if so, the nature of the conflict and how the conflict is being addressed.

The initial and expanded SEC disclosure rules were introduced without any evidence that “conflicted consultants” were, indeed, complicit in perceived pay excesses. Based on the initial year of consultant disclosures, Cadman, Carter, and Hillegeist (2010) find no evidence that CEO pay is related to consultant conflicts of interest. Based on similar data (supplemented with IRS and Department of Labor data identifying actuarial service providers), Murphy and Sandino (2010) find some evidence that CEO pay is modestly higher in firms where consultants provide other services. However, in subsequent time-series analyses, Murphy and Sandino (2012) show that the relation between conflicted consultants and CEO pay had become statistically and economically insignificant by 2008.

While the evidence suggests, at most, a modest link between conflicted consultants and CEO pay, the SEC disclosure requirements have resulted in dramatic changes in the compensation consulting industry. The largest full-service consulting firms in 2006 (Towers Perrin, Mercer, Hewitt, and Watson Wyatt) have experienced significant declines in market share among their S&P 500 clients, while the largest non-integrated firms focused only on executive compensation (Frederick Cook and Co. and Pearl Meyer) have increased market share. In addition, many of the top consultants from the full-service firms left to create their own “boutique” firms focused on advising boards. For example, consultants from Towers Perrin and Watson Wyatt formed Pay Governance, consultants from Hewitt formed Meridian Compensation Partners, and consultants from Mercer formed Compensation Advisory Partners. The full-service firms have also consolidated: Towers Perrin and Watson Wyatt merged to create TowersWatson, while Hewitt was acquired by Aon.

As discussed by Murphy and Sandino (2010), the experience of the full-service consulting firms closely parallels the experience of accounting firms offering both auditing and consulting services. Concerns regarding conflicts when accounting firms offered services beyond auditing led not only to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act and to detailed disclosures of fees charged for auditing and non-auditing businesses, but also to the practice of companies avoiding using their auditors for other services. This practice has defined the industry, in spite of the fact that the auditors (with their vast firm-specific knowledge) might be the efficient provider of such services, and notwithstanding the fact that there was no direct evidence that these potential conflicts actually translated into misleading audits.

3.9 Pay Restrictions for TARP Recipients (2008–2009)

3.9.1 The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (EESA)

On September 19, 2008—at the end of a tumultuous week on Wall Street that included the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy and the hastily arranged marriage of Bank of America and Merrill Lynch—Treasury Secretary Paulson asked Congress to approve the Administration’s plan to use taxpayers’ money to purchase “hundreds of billions” in illiquid assets from US financial institutions.135 Paulson’s proposal contained no constraints on executive compensation, fearing that restrictions would discourage firms from selling potentially valuable assets to the government at relatively bargain prices.136 Limiting executive pay, however, was a long-time top priority for Democrats and some Republican congressmen, who viewed the “Wall Street bonus culture” as a root cause of the financial crisis. Congress rejected the bailout bill on September 30, but reconsidered three days later after a record one-day point loss in the Dow Jones Industrial Average and strong bipartisan Senate support. The Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (EESA) was passed by Congress on October 3rd, and signed into law by President Bush on the same day.

When Treasury invited (or, in some cases, coerced) the first eight banks to participate in TARP, a critical hurdle involved getting the CEOs and other top executives to waive their rights under their existing compensation plans. At the time, the proposed restrictions seemed serious. For example, while Section 304 of the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act required clawbacks of certain executive ill-gotten incentive payments, the Act only covered the CEO and chief financial officer (CFO), and only covered accounting restatements. While applying only to TARP recipients (Sarbanes-Oxley applied to all firms), the October 2008 EESA covered the top-five executives (and not just the CEO and CFO), and covered a much broader set of material inaccuracies in performance metrics. In addition, EESA lowered the IRS cap on deductibility for the top-five executives from $1 million to $500,000, and applied this limit to all forms of compensation (and not just non-performance-based pay). EESA also prohibited new golden parachutes agreements for the Top 5 executives, and capped payments under existing plans to 300% of the executives’ average taxable compensation over the prior five years.

In a semantic change that will confuse students of executive compensation for years to come, EESA also formally defined “golden parachutes” as amounts paid in “the event of an involuntary termination, bankruptcy filing, insolvency, or receivership”. Previously, the term “golden parachute” had referred exclusively (if not pejoratively) to payments made in connection with a change in control. Under IRS Section 280(G) (discussed above in Section 3.6.1), change-in-control payments exceeding 300% of executives’ average taxable compensation over the prior five years were subject to significant tax penalties. Thus, EESA not only explicitly capped payments, but substantially expanded the events characterized as golden parachutes.

3.9.2 The American Reinvestment and Recovery Act (ARRA) Amends EESA

In January 2009, reports began surfacing that Merrill Lynch distributed $3.6 billion in bonuses to its 36,000 employees just before the completion of the merger with Bank of America: the top 14 bonus recipients received a combined $250 million, while the top 149 received $858 million (Cuomo, 2009). The CEOs of Bank of America and the former Merrill Lynch (neither of whom received a bonus for 2008) were quickly hauled before Congressional panels outraged by the payments, and the Attorney General of New York launched an investigation to determine if shareholders voting on the merger were misled about both the bonuses and Merrill’s true financial condition. The SEC joined in with its own civil complaint, which sued the Bank of America but not its individual executives, and the bank agreed to settle for $33 million. However, a few weeks later a federal judge threw out the proposed settlement, insisting that individual executives be charged and claiming that the settlement did not comport with the most elementary notions of justice and morality.137 In February 2010, the judge relented and reluctantly approved the settlement after it had been increased to $150 million.138

By the time the Merrill Lynch bonuses were revealed, the country had a new President, a new Congress, and new political resolve to punish the executives in the companies perceived to be responsible for the global meltdown. Indicative of the mood in Washington, Senator McCaskill (D-Missouri) introduced a bill in January 2009 that would limit total compensation for executives at bailed-out firms to $400,000, calling Wall Street executives “a bunch of idiots who were kicking sand in the face of the American taxpayer”.139

On February 4, 2009, President Obama’s administration responded with its own proposal for executive-pay restrictions that distinguished between failing firms requiring exceptional assistance and relatively healthy firms participating in TARPs Capital Purchase Program. Most importantly, the Obama Proposal for exceptional assistance firms (which specifically identified AIG, Bank of America, and Citigroup) capped annual compensation for senior executives to $500,000, except for restricted stock awards (which were not limited, but could not be sold until the government was repaid in full, with interest). In addition, for exceptional-assistance firms the number of executives subject to clawback provisions would be increased from 5 under EESA to 20, and the number of executives with prohibited golden parachutes would be increased from 5 to 10. In addition, the next 25 highest-paid executives would be prohibited from parachute payments that exceed one year’s compensation.

Moreover—in response to reports of office renovations at Merrill Lynch, corporate jet orders by Citigroup, and corporate retreats by AIG—the Obama Proposal stipulated that all TARP recipients adopt formal policies on luxury expenditures. Finally, the Obama Proposal required all TARP recipients to fully disclose their compensation policies and allow nonbinding Say-on-Pay shareholder resolutions.140

In mid-February 2009, separate bills proposing amendments to EESA had been passed by both the House and Senate, and it was up to a small conference committee to propose a compromise set of amendments that could be passed in both chambers. On February 13—as a last-minute addition to the amendments—the conference chairman (Senator Chris Dodd) inserted a new section imposing restrictions on executive compensation that were opposed by the Obama administration and severe relative to both the limitations in the October 2008 version and the February 2009 Obama Proposal. Nonetheless, the compromise was quickly passed in both chambers with little debate and signed into law as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 by President Obama on February 17, 2009.

Table 1 compares the pay restrictions under the original 2008 EESA bill, the 2009 Obama Proposal, and the 2009 ARRA (which amended Section 111 of the 2008 EESA). While the clawback provisions under the original ESSA covered only the top-five executives (up from only two in SOX), the Dodd Amendments extended these provisions to 25 executives and applied them retroactively.141 In addition, while the original ESSA disallowed severance payments in excess of 300% of base pay for the top five executives, the Dodd Amendments covered the top 10 executives and disallowed all payments (not just those exceeding 300% of base). Most importantly, the Dodd Amendments allowed only two types of compensation: base salaries (which were not restricted in magnitude), and restricted stock (limited to grant-date values no more than half of base salaries). The forms of compensation explicitly prohibited under the Dodd amendments for TARP recipients include performance-based bonuses, retention bonuses, signing bonuses, severance pay, and all forms of stock options.

Table 1 Comparison of Pay Restrictions in EESA (2008), Obama Proposal (2009), and ARRA (2009)

Finally, the Dodd amendments imposed mandatory Say-on-Pay resolutions for all TARP recipients. In early 2009—not long after the Dow Jones Industrial Average hit its crisis minimum at about 6500—shareholders had an opportunity to provide a non-binding vote of approval on the 2008 compensation received by the top executives at the TARP recipients (i.e. compensation for the year when these firms allegedly dragged the economy into a financial crisis). As an interesting historical footnote, none of the TARP recipients received a majority vote against its executive compensation levels and policies.

As another interesting historical footnote: while almost all attempts to regulate executive compensation have produced negative unintended side affects, the Dodd Amendments produced a positive one. In particular, many TARP recipients found the draconian pay restrictions sufficiently onerous that they hurried to pay back the government in time for year-end bonuses.

As draconian as the Dodd Amendments (triggered by the Merrill Lynch payments) were, things were about to get worse. The second flash point for outrage over bonuses involved insurance giant American International Group (AIG), which had received over $170 billion in government bailout funds, in large part to offset over $40 billion in credit default-swap losses from its Financial Products unit. In March 2009, AIG reported it was about to pay $168 million as the second installment of $450 million in contractually obligated retention bonuses to employees in the troubled unit. (The public outrage intensified after revelations that most of AIGs bailout money had gone directly to its trading partners, including Goldman Sachs ($13 billion), Germanys Deutsche Bank ($12 billion), and France’s Société Générale ($12 billion)). The political fallout was swift and furious: in the week following the revelations seven bills were introduced in the House and Senate aimed specifically at bonuses paid by AIG and other firms bailed out through TARP:

• H.R. 1518, the Bailout Bonus Tax Bracket Act of 2009 imposed a 100% tax on bonuses over $100,000.

• H.R. 1527 imposed an additional 60% tax (on top of 35% ordinary income tax) on bonuses exceeding $100,000 paid to employees of businesses in which the federal government has an ownership interest of 79% or more. (Not coincidentally, the government owned 80% of AIG when the bill was introduced).

• H.R. 1575, the End Government Reimbursement of Excessive Executive Disbursements Act (i.e. the End GREED Act) authorized the Attorney General to seek recovery of and limit excessive compensation.

• H.R. 1577, the AIG Bonus Payment Bill required the Secretary of Treasury to implement a plan within two weeks to thwart the payment of the AIG bonuses, and required Treasury approval of any future bonuses by any TARP recipient.

• H.R. 1586 sought to impose a 90% income tax on bonuses paid by TARP recipients; employees would be exempt from the tax if they returned the bonus in the year received.

• S. 651, the Compensation Fairness Act of 2009, imposed a 70% excise tax (half paid by the employee and half by the employer) for any bonus over $50,000 paid by a TARP firm.

• H.R. 1664, the Pay for Performance Act of 2009 prohibited any compensation payment (under existing as well as new plans) if such compensation: (1) is deemed unreasonable or excessive by the Secretary of the Treasury; and (2) includes bonuses or retention payments not directly based on approved performance measures. The bill also created a Commission on Executive Compensation to study and report to the President and Congress on the compensation arrangements at TARP firms.

Most of these bills were either stalled in committees or failed in a vote, although many features of H.R. 1664 were incorporated into the July 2010 Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform bill discussed below. Therefore, the reason to list the bills above is not for their ultimate relevance to policy, but rather as evidence of Congressional outrage and a political resolve to punish Wall Street for its bonus practices.

While details on the compensation of the five highest-paid executive officers are publicly disclosed and widely available, banks have historically been highly secretive about the magnitude and distribution of bonuses for its traders and investment bankers. Indeed, since the SEC disclosure rules only apply to executive officers, the banks can have non-officer employees making significantly more than the highest-paid officers. Following the Merrill Lynch and AIG revelations, New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo subpoenaed bonus records from the nine original TARP recipients, arguing that New York law allows creditors to challenge any payment by a company if the company did not get adequate value in return. His report—published in late July 2009—was provocatively titled: No Rhyme or Reason: The Heads I Win, Tails You Lose Bank Bonus Culture.

Table 2 summarizes the distribution of bonuses for the nine original TARP recipients, based on data from the Cuomo (2009) report. The table shows, for example, that 738 Citigroup employees received bonuses over $1 million, and 124 received over $3 million, in a year when the bank lost nearly $30 billion. The 2008 bonus pools exceeded annual earnings in six of the nine banks; in aggregate the banks paid $32.6 billion in bonuses while losing $81.4 billion in earnings. Not surprising, the Cuomo report further fueled outrage over Wall Street bonuses on both Main Street and in Washington.

Table 2 2008 Earnings and Bonus Pools for Eight Original TARP Recipients

Source: Cuomo (2009). Wells Fargo losses include losses from Wachovia (acquired in December 2008).

3.9.3 Treasury Issues Final Rules and Appoints a Pay Czar