Chapter 1

AJAX Essentials

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding AJAX

Understanding AJAX

![]() Using JavaScript to manage HTTP requests

Using JavaScript to manage HTTP requests

![]() Creating an XMLHttpRequest object

Creating an XMLHttpRequest object

![]() Building a synchronous AJAX request

Building a synchronous AJAX request

![]() Retrieving data from an AJAX request

Retrieving data from an AJAX request

![]() Managing asynchronous AJAX requests

Managing asynchronous AJAX requests

If you've been following web trends, you've no doubt heard of AJAX. This technology has generated a lot of interest. In this chapter, I show you what AJAX really is, how to use it, and how to use a particular AJAX library to supercharge your web pages.

The first thing is to figure out exactly what AJAX is and what it isn't. It isn't

- A programming language: It isn't one more language to learn along with the many others you encounter.

- New: Most of the technology used in AJAX isn't really all that new; it's the way the technology is being used that's different.

- Remarkably different: For the most part, AJAX is about the same things you'll see in the rest of this book: building compliant web pages that interact with the user.

So you have to be wondering why people are so excited about AJAX. It's a relatively simple thing, but it has the potential to change the way people think about Internet development. Here's what it really is:

- Direct control of client-server communication: Rather than the automatic communication between client and server that happens with web forms and server-side programs, AJAX is about managing this relationship more directly.

- Use of the XMLHttpRequest object: This is a special object that's been built into the DOM of all major browsers for some time, but it wasn't used heavily. The real innovation of AJAX was finding creative (and perhaps unintentional) uses for this heretofore virtually unknown utility.

- A closer relationship between client-side and server-side programming: Up to now, client-side programs (usually JavaScript) did their own thing, and server-side programs (PHP) operated without too much knowledge of each other. AJAX helps these two types of programming work together better.

- A series of libraries that facilitate this communication: AJAX isn't that hard, but it does have a lot of details. Several great libraries have sprung up to simplify using AJAX technologies. You can find AJAX libraries for both client-side languages, like JavaScript, and server-side languages, like PHP.

Perhaps you're making an online purchase with a shopping-cart mechanism.

In a typical (pre-AJAX) system, an entire web page is downloaded to the user's computer. There may be a limited amount of JavaScript-based interactivity, but anything that requires a data request needs to be sent back to the server. For example, if you're on a shopping site and you want more information about that fur-lined fishbowl you've had your eye on, you might click the More Information button. This causes a request to be sent to the server, which builds an entirely new web page for you containing your new request.

Every time you make a request, the system builds a whole new page on the fly. The client and server have a long-distance relationship.

In the old days when you wanted to manage your website's content, you had to refresh each web page — time-consuming to say the least. But with AJAX, you can update the content on a page without refreshing the page. Instead of the server sending an entire page response just to update a few words on the page, the server just sends the content you want to update and nothing else.

If you're using an AJAX-enabled shopping cart, you might still click the fishbowl image. An AJAX request goes to the server and gets information about the fishbowl, which is immediately placed on the current page, without requiring a complete page refresh.

AJAX technology allows you to send a request to the server, which can then change just a small part of the page. With AJAX, you can have a whole bunch of smaller requests happening all the time, rather than a few big ones that rebuild the page in large, distracting flurries of activity.

Google's Gmail was the first major application to use AJAX, and it blew people away because it felt so much like a regular application inside a web browser.

AJAX Spelled Out

Technical people love snappy acronyms. Nothing is more intoxicating than inventing a term. AJAX is one term that has taken on a life of its own. Like many computing acronyms, it may be fun to say, but it doesn't really mean much. AJAX stands for Asynchronous JavaScript And XML. Truthfully, these terms were probably chosen to make a pronounceable acronym rather than for their accuracy or relevance to how AJAX works.

A is for asynchronous

An asynchronous transaction (at least in AJAX terms) is one in which more than one thing can happen at once. For example, you can make an AJAX call process a request while the rest of your form is being processed. AJAX requests do not absolutely have to be asynchronous, but they usually are.

When it comes to web design, asynchronous means that you can independently send and receive as many different requests as you want. Data may start transmitting at any time without having any effect on other data transmissions. You could have a form that saves each field to the database as soon as it's filled out, or perhaps a series of drop-down lists that generate the next drop-down list based on the value you just selected. (It's okay if this doesn't make sense right now. It's not an important part of understanding AJAX, but vowels are always nice in an acronym.)

In this chapter, I show you how to do both synchronous and asynchronous versions of AJAX.

J is for JavaScript

If you want to make an AJAX call, you simply write some JavaScript code that simulates a form. You can then access a special object hidden in the DOM (the XMLHttpRequest object) and use its methods to send that request to the user. Your program acts like a form, even if there was no form there. In that sense, when you're writing AJAX code, you're really using JavaScript. Of course, you can also use any other client-side programming language that can speak with the DOM, including Flash and (to a lesser extent) Java. JavaScript is the dominant technology, so it's in the acronym.

A lot of times, you also use JavaScript to decode the response from the AJAX request.

A is for . . . and?

I think it's a stretch to use And in an acronym, but AJX just isn't as cool as AJAX. They didn't ask me.

And X is for . . . data

The X is for XML, which is one way to send the data back and forth from the server. Because the object you're using is the XMLHttpRequest object, it makes sense that it requests XML. It can do that, but it can also get any kind of text data. You can use AJAX to retrieve all kinds of things:

- Plain old text: Sometimes you just want to grab some text from the server. Maybe you have a text file with a daily quote in it or something.

- Formatted HTML: You can have text stored on the server as a snippet of HTML/XHTML code and use AJAX to load this page snippet into your browser. This gives you a powerful way to build a page from a series of smaller segments. You can use this to reuse parts of your page (say, headings or menus) without duplicating them on the server.

- XML data: XML is a great way to pass data around. (That's what it was invented for.) You might send a request to a program that goes to a database, makes a request, and returns the result as XML.

- JSON data: A newer standard called JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is emerging as an alternative to XML for formatted data transfer. It has some interesting advantages. You might have already built JSON objects in Book IV, Chapter 4. You can read in a text file already formatted as a JavaScript object.

Making a Basic AJAX Connection

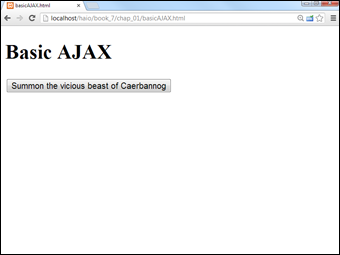

The basicAJax.html program shown in Figure 1-1 illustrates AJAX at work.

Figure 1-1: Click the button and you'll see some AJAX magic.

When the user clicks the link, the small pop-up shown in Figure 1-2 appears.

Figure 1-2: This text came from the server.

It's very easy to make JavaScript pop up a dialog box, but the interesting thing here is where that text comes from. The data is stored on a text file on the server. Without AJAX, you don't have an easy way to get data from the server without reloading the entire page.

This particular example uses a couple of shortcuts to make it easier to understand:

- The program isn't fully asynchronous. The program pauses while it retrieves data. As a user, you probably won't even notice this, but as you'll see, this can have a serious drawback. But the synchronous approach is a bit simpler, so I start with this example and then extend it to make the asynchronous version.

- This example isn't completely cross-browser compatible. The AJAX technique I use in this program works fine for IE 7 and later and all versions of Firefox (and most other standards-compliant browsers). It does not work correctly in IE 6 and earlier. I recommend that you use jQuery or another library (described in Chapter 2 of this minibook) for cross-browser compatibility.

Look over the following code, and you'll find it reasonable enough:

<!DOCTYPE HTML>

<html lang="en";>

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>basicAJAX.html</title>

<script type = "text/javascript">

function getAJAX(){

var request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.open("GET", "beast.txt", false);

request.send(null);

if (request.status == 200){

//we got a response

alert(request.responseText);

} else {

//something went wrong

alert(“Error- " + request.status + ": " + request.statusText);

} // end if

} // end function

</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Basic AJAX</h1>

<form action = "">

<p>

<button type = "button"

onclick = "getAJAX()">

Summon the vicious beast of Caerbannog

</button>

</p>

</form>

</body>

</html>

Building the HTML form

You don't absolutely need an HTML form for AJAX, but I have a simple one here. Note that the form is not attached to the server in any way.

<form action = "">

<p>

<button type = "button"

onclick = "getAJAX()">

Summon the vicious beast of Caerbannog

</button>

</p>

</form>

This page is set up like a client-side (JavaScript) interaction. The form has an empty action element. The code uses a button (not a submit element), and the button is attached to a JavaScript function called getAJAX().

All you really need is some kind of structure that can trigger a JavaScript function.

Creating an XMLHttpRequest object

The key to AJAX is a special object called XMLHttpRequest. All the major browsers have it, and knowing how to use it in code is what makes AJAX work. It's pretty easy to create:

var request = new XMLHttpRequest();

This line makes an instance of the XMLHttpRequest object. You use methods and properties of this object to control a request to the server.

AJAX is really nothing more than HTTP, the protocol that your browser and server quietly use all the time to communicate with each other. You can think of an AJAX request like this: Imagine that you have a basket with a balloon tied to the handle and a long string. As you walk around the city, you can release the basket under a particular window and let it rise. The window (server) puts something in the basket, and you can then wind the string to bring the basket back down and retrieve the contents. The various characteristics of the XMLHttpRequest object are described in Table 1-1.

Table 1-1 Useful Members of the XMLHttpRequest Object

|

Member |

Description |

Basket Analogy |

|

open(protocol, URL, synchronization) |

Opens a connection to the indicated file on the server. |

Stand under a particular window. |

|

send(parameters) |

Initiates the transaction with given parameters (or null). |

Release the basket but hang on to the string. |

|

status |

Returns the HTTP status code returned by the server (200 is success). |

Check for error codes (“window closed,” “balloon popped,” “string broken,” or “everything's great”). |

|

statusText |

Text form of HTTP status. |

Text form of status code. |

|

responseText |

Text of the transaction's response. |

Get the contents of the basket. |

|

readyState |

Describes the current status of the transaction (4 is complete). |

Is the basket empty, going up, coming down, or here and ready to get contents? |

|

onReadyStateChange |

Event handler. Attach a function to this parameter, and when the readyState changes, the function will be called automatically. |

What should I do when the state of the basket changes? For example, should I do something when I've gotten the basket back? |

Opening a connection to the server

The XMLHttpRequest object has several useful methods. One of the most important is the open() method:

request.open("GET", "beast.txt", false);

The open() method opens a connection to the server. As far as the server is concerned, this connection is identical to the connection made when the user clicks a link or submits a form. The open() method takes the following three parameters:

- Request method: The request method describes how the server should process the request. The values are identical to the form method values described in Book V, Chapter 3. Typical values are GET and POST.

- A file or program name: The second parameter is the name of a file or program on the server. This is usually a program or file in the same directory as the current page.

- A synchronization trigger: AJAX can be done in synchronous or asynchronous mode. (Yeah, I know, then it would just be JAX, but stay with me here.) The synchronous form is easier to understand, so I use it first. The next example (and all the others in this book) uses the asynchronous approach.

For this example, I use the GET mechanism to file called beast.txt from the server in synchronized mode.

Sending the request and parameters

After you've opened a request, you need to pass that request to the server. The send() method performs this task. It also provides you with a mechanism for sending data to the server. This only makes sense if the request is going to a PHP program (or some other program on the server). Because I'm just requesting a regular text document, I send the value null to the server. Chapter 6 of this minibook describes how to work with other kinds of data.

request.send(null);

This is a synchronous connection, so the program pauses here until the server sends the requested file. If the server never responds, the page will hang. (This is exactly why you usually use asynchronous connections.) Because this is just a test program, assume that everything will work okay and motor on.

Returning to the basket analogy, the send() method releases the basket, which floats up to the window. In a synchronous connection, you assume that the basket is filled and comes down automatically. The next step doesn't happen until the basket is back on earth. (But if something went wrong, the next step may never happen because the basket will never come back.)

Checking the status

The XMLHttpRequest object has a property called status that returns the HTTP status code. If the status is 200, everything went fine and you can proceed. If the status is some other value, some type of error occurred.

You can check for all the various status codes if you want, but for this simple example, I'm just ensuring that the status is 200:

if (request.status == 200){

//we got a response

alert(request.responseText);

} else {

//something went wrong

alert("Error- " + request.status + ": " + request.statusText);

} // end if

The status property is like looking at the basket after it returns. It might have the requested data in it, or it might have some sort of note. (“Sorry, the window was closed. I couldn't fulfill your request.”) There's not much point in processing the data if it didn't return successfully.

Of course, I could do a lot more with the data. If it's already formatted as HTML code, I can use the innerHTML DOM tricks described in Book IV to display the code on any part of my page. It might also be some other type of formatted data (XML or JSON) that I can manipulate with JavaScript and do whatever I want with.

All Together Now — Making the Connection Asynchronous

The synchronous AJAX connection described in the previous section is easy to understand, but it has one major drawback: The client's page stops processing while waiting for a response from the server. This doesn't seem like a big problem, but it is. If aliens attack the web server, it won't make the connection, and the rest of the page will never be activated. The user's browser hangs indefinitely. In most cases, the user will have to shut down the browser process by pressing Ctrl+Alt+Delete (or the similar procedure on other OSs). Obviously, it would be best to prevent this kind of error.

In other words, the readyState property is like looking at the basket's progress. The basket could be sitting there empty because you haven't begun the process. It could be going up to the window, being filled, coming back down, or it could be down and ready to use. You're only concerned with the last state because that means the data is ready.

The asynchronous version looks exactly the same on the front end, but the code is structured a little differently:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8">

<title>asynch.html</title>

<script type = "text/javascript">

var request; //make request object a global variable

function getAJAX(){

request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.open("GET", "beast.txt");

request.onreadystatechange = checkData;

request.send(null);

} // end function

function checkData(){

if (request.readyState == 4) {

// if state is finished

if (request.status == 200) {

// and if attempt was successful

alert(request.responseText);

} // end if

} // end if

} // end checkData

</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Asynchronous AJAX transmission</h1>

<form action = "">

<p>

<button type = "button"

onclick = "getAJAX()">

Summon the beast of Caerbannogh

</button>

</p>

</form>

</body>

</html>

Setting up the program

The general setup of this program is just like the earlier AJAX example. The HTML is a simple button that calls the getAJAX() function.

Note that in the JavaScript code, I made the XMLHttpRequest object (request) a global variable by declaring it outside any functions. I generally avoid making global variables, but it makes sense in this case because I have two different functions that require the request object.

Building the getAJAX() function

The getAJAX() function sets up and executes the communication with the server:

function getAJAX(){

request = new XMLHttpRequest();

request.open("GET", "beast.txt");

request.onreadystatechange = checkData;

request.send(null);

} // end function

The code in this function is pretty straightforward:

- Create the request object.

The request object is created exactly as it was in the first example in the section “Creating an XMLHttpRequest object,” earlier in this chapter.

- Call request's open()method to open a connection.

Note that this time I left the synchronous parameter out, which creates the (default) asynchronous connection.

- Assign an event handler to catch responses.

You can use event handlers much like the ones in the DOM. In this particular case, I'm telling the request object to call a function called checkData whenever the state of the request changes.

You can't easily send a parameter to a function when you call it using this particular mechanism. That's why I made request a global variable.

You can't easily send a parameter to a function when you call it using this particular mechanism. That's why I made request a global variable. - Send the request.

As before, the send() method begins the process. Because this is now an asynchronous connection, the rest of the page continues to process. As soon as the request's state changes (hopefully because a successful transfer has occurred), the checkData function is activated.

Reading the response

Of course, you now need a function to handle the response when it comes back from the server. This works by checking the ready state of the response. Any HTTP request has a ready state, which is a simple integer value that describes what state the request is currently in. You find many ready states, but the only one you're concerned with is 4, meaning that the request is finished and ready to process.

function checkData(){

if (request.readyState == 4) {

// if state is finished

if (request.status == 200) {

// and if attempt was successful

alert(request.responseText);

} // end if

} // end if

} // end checkData

Once again, you can do anything you want with the text you receive. I'm just alerting it, but the data can be incorporated into the page or processed in any way you want.

To the user, this makes the web page look more like traditional applications. This is the big appeal of AJAX: It allows web applications to act more like desktop applications, even if these web applications have complicated features like remote database access.

To the user, this makes the web page look more like traditional applications. This is the big appeal of AJAX: It allows web applications to act more like desktop applications, even if these web applications have complicated features like remote database access. AJAX uses some pretty technical parts of the web in ways that may be unfamiliar to you. Read through the rest of this chapter so that you know what AJAX is doing, but don't get bogged down in the details. Nobody does it by hand! (Except people who write AJAX libraries or books about using AJAX.) In Chapter

AJAX uses some pretty technical parts of the web in ways that may be unfamiliar to you. Read through the rest of this chapter so that you know what AJAX is doing, but don't get bogged down in the details. Nobody does it by hand! (Except people who write AJAX libraries or books about using AJAX.) In Chapter  You might claim that HTML frames allow you to pull data from the server, but frames have been deprecated in modern versions of HTML because they cause a lot of other problems. You can use a frame to load data from the server, but you can't do all the other cool things with frame-based data that you can with AJAX. Even if frames were allowed, AJAX is a much better solution most of the time.

You might claim that HTML frames allow you to pull data from the server, but frames have been deprecated in modern versions of HTML because they cause a lot of other problems. You can use a frame to load data from the server, but you can't do all the other cool things with frame-based data that you can with AJAX. Even if frames were allowed, AJAX is a much better solution most of the time.