With an understanding of the process used to apply the cinematic style to client-based work, including ways to develop a story (Chapter 1) and the foundation for the vision of your company laid out (Chapter 2), the company’s legalities must be discussed. Before getting clients, developing a project, and going into production, you need to actually form your company as a legal entity. In this way, the company (and you) are protected. This includes issuing contracts, getting insurance, discovering resources for music rights, and paying taxes. Without legal standing and the knowledge of your rights and the rights of others, your business will not last. This chapter will go over the process of:

- Creating a limited liability company (or corporation) (LLC).

- Using contracts (work with clients, locations, talent, music rights, etc.), including model contracts from Zandrak.

- Thinking about music rights.

- Getting insurance—what you need to cover your gear.

Turning Zandrak into an LLC

Andrew Hutcheson founded Zandrak while studying film at Emerson College in Boston. He ended up editing field documentary footage for an anthropology professor, and she wanted him to travel to India to help do the work and to pay him for the gig. He had run his own business in high school, where he filmed sports videos, creating admissions tapes for high-school athletes applying to different universities. So Andrew created an LLC to make his job official and to protect his assets since it was his first big job. He researched how to set up a limited liability company (LLC) on the web, and established Zandrak.

Andrew was inspired by his father who runs his own business doing color management for print and photo industries. He talked to his father about how he set up his business. “I was reading about how you incorporate, and things that were way above my head. I didn’t need a pension and health plan. I’m one guy. But then through searching around I found out about an LLC.” Andrew’s search began with watching 500 Days of Summer. “I noticed there was a company listed in the end credits called 500DS Films, Inc. as a production company.” Curious, he looked up that company and discovered it was “just the entity that was made for the film.” He realized there was a legal entity just for the one film, he explains, “and that every time you make a film, you make an LLC or an S-Corp.” There are different benefits depending on the nature of the film and how you plan on structuring your legal entity, Andrew explains. “And the executive producers, the directors, and the head people are part of it.”

Andrew dug deeper into the process on how to create an LLC and found that he could file it online. This was in 2010. He was nineteen at the time. He started Zandrak in New Jersey, where his parents live, as it was cheaper with a filing fee of $150. In Massachusetts he would have had to pay $500. Once he set up Zandrak as an LLC, “I used that as the vehicle for me to be able to go over to India and get paid on my first official gig through my company. I was over there for a month shooting and editing three different ethnographic documentaries.”

His father had instilled within Andrew the importance of getting paid for work. “‘If you aren’t getting paid, it’s a hobby not a career,’” he told me. “That stayed with me for a while because it’s not necessarily something that I essentially agree with.” There are filmmakers who do work for free, but they “find a way to make a career out of it! But what my father told me definitely stuck with me—I have to make money.” When he was doing the high-school sports videos, his father told him that if he wanted to get more tapes to shoot footage, then he wasn’t going to pay for additional tapes. Andrew had to find a way to make money in order to get the supplies he needed, so he became entrepreneurial and charged enough money to make a profit and use some of the money to buy the tapes.

Creating an LLC

You may think that since you’re not setting up a business with a formal office, administrative assistant, and other employees that you can just work out of your home and not worry about all the legal paperwork. This is called a DBA (doing business as . . . company name). But in this situation, you’re personally liable for everything, including your personal assets. If you file as an LLC, and then go bankrupt or are sued, only the company’s assets are liable. Your personal property is protected from any damage.

To form an LLC, look up the rules in the state government for your particular state. Each one is different and priced differently. Do a web search and find the .gov website as it relates to LLC. There are businesses that will charge you a fee to file for you, but you don’t need to pay someone, since you can do the work yourself and it’s not complex. Here’s part of the process I went through in the state of Arizona.

- Determine the relative merits of where you incorporate. In terms of getting sued and tax breaks, this could make a big difference to where you run your business.

- Do a web search and find the corporation division of the state government. The one you want is the .gov site.

- At the government corporation site, find the LLC link that takes you to the LLC forms for your state.

- There may be a lot of forms listed, but you only need a few and there will likely be links to instructions on how to fill out the form. Choose the forms you need. Most of the forms are for changes you may need to make, such as changing an address or correcting an error. For Arizona, I found the ones I needed were:

- Articles of Organization

- Articles of Organization for an LLC in the state of Arizona. Put in the name of your company—be sure to do a search to make sure your name is original in the state, otherwise the form will get bounced back and you’ll need to resubmit with another fee. Input in your name and address, and unless you have the startup funds to open your own office space, the business address will be your home address. If the LLC has a planned limited duration, you will be asked to provide dates. The rest of the form will typically have a place for the name and address for everyone who is a partner in the LLC.

- Manager Structure Attachment

This form simply lists the name and address of the partners in the LLC. If you don’t have any partners, then you will write your company name and your name and address. I check off everyone as a manager since we have equal power and stake in the company. - Statutory Agent Acceptance

You will need to sign off as the legal representative of the company. There needs to be one person who accepts the legal responsibility for the company, and is the contact for it. You will not have the A.C.C. file number if you’re just creating the company, so leave this blank. You’ll be given the number after you file. - Cover sheet (under miscellaneous forms)

Arizona has a cover sheet that goes on top of your other documents and is the checklist for your payment. This requires you to check off everything you’re doing (with a different form for each). I check off the Articles of Organization and include a $50 fee (each state will be different) for regular service. If you need it before 30 days, pay the expedited fee. Include the name of the company and your email, as well as your name and contact information.

Click on each one and download them, as well as the instructions.

Every state will have different types of forms, but the principle and ideas are the same. You’re forming a company, naming it, and you’re telling everyone that you’re in charge of the company, and where it legally exists (address). In addition to the state forms, Arizona law requires an LLC to place an advertisement in a local newspaper, so that there is a public record of it. Many newspapers will have a standard fee and a form to fill out.

Contracts

Contracts are what keeps your company legal. Andrew Hutcheson at Zandrak hired a lawyer to review his contracts. Once he had a set of contracts that legally cleared, he didn’t need to go back and clear every new contract with a lawyer. Online, I supply a set of contracts (courtesy of Zandrak) and other forms that can be used for your work. You may adopt them for your own use, but it is your responsibility to hire a lawyer to make sure the contracts will do what you want them to do for your business. These are offered as educational models.

At Zandrak, Andrew Hutcheson explains, if the client likes the idea and approves the budget, “we make a treatment, this goes hand in hand with the production agreement that we’ll make for the client once they like everything. We’ll put all of that into a contract, and include deadlines, the schedule, and we make a treatment that portrays everything, the entire idea, how we’re going execute it, style, storyboards.” Chapter 6 will cover writing and pitching proposals and treatments, but the key point, here, is getting the contract settled.

See http://kurtlancaster.com/contracts-and-forms/ for the following downloadable contracts and forms:

- Location Release Form

In most—if not in every—case, you will want permission to shoot on location. This form provides it. It also emphasizes that the location is not liable for the production—which is why the production must have liability insurance, and the insurance will go a long way in securing permission from the property owner. - Production Agreement

The sample production agreement contract provides a strong foundation of protection, understanding, and scope of what a project could entail with a client. If you don’t have a limit on the number of edits, for example, a client could keep taking advantage on many edits. But agreeing on three edits with new charges for additional edits protects you from a project that never ends. In either case, you will want to put this material in a contract. - Independent Contractor Agreement

The parameters of a person’s role on a job. Use this if you’re hiring someone for a particular task. You can also use it as the basis for a freelance job. - Performer Agreement

Similar to the Standard Release Form (which covers everyone appearing in your project, including extras and those with nonspeaking roles), the Performer Agreement lays out the specifics for performers you hire for your projects, such as actors. It’s tailored to detail their duties, your expectations, and what their expectations are as to schedule, meals, travel, and so forth. - Standard Release Form

This is key for any documentary interview or any shot that captures a recognizable person in the background of a shot. Get permission from anyone you shoot, so that there are no hassles when it comes to finishing the project. If you don’t have a person’s permission, you may run into legal issues, especially if you’re using it for film or broadcast distribution. When Zandrak produced “Still Life” in New York City, Charles Frank and Jake Oleson shot great-looking footage. Andrew Hutcheson followed in their footsteps, going up to every person they shot and getting a release form signed. - Production Quote Form

Zandrak’s quote sheet. Use when submitting an estimated budget to a client, and include it in your bid. - Budget Form

A standard film budget. Use it to show what you need to run the budget for a particular project. Some material may not be needed, but it’ll cover nearly every type of role in a production. - Call Sheet

Provided by Stillmotion, this template allows you to set your daily shoot schedule, contact information, and location for your talent and crew. - Budget Expense Worksheet

This will allow you to calculate your monthly expenses and so determine the cost of doing business. Change the Excel spreadsheet as needed.

In discussing a production agreement, Patrick Moreau of Stillmotion emphasizes that you want to “have a lot of clarity around revisions and process. You can do a wedding, for example, where a couple can have you doing revisions for months if you have not set the right expectations.” Building the right relationship and setting proper expectations in writing marks you as a professional. “So if you’ve done the right communicating and set the right expectations” then everyone is happy, he explains. “We’re done when you’re happy; we’re done when we all come to that same place.” This might mean “a big detour and seventeen more revisions than you thought, but sometimes it also means there’s absolutely nothing.” By putting the expectations in place and allowing room for revising those expectations in the contract, then there’s no hidden charges.

Patrick mentions how, “We’ve done projects where we’ve turned it in and there’s been zero revision—they just love it.” But “if we think somebody’s being unreasonable or excessive with requests for changes or not improving the story, then we’ll make it clear on the limit to revisions that are allowed.” In short, he notes, “We’ll do one more round of edits and we’ll start talking about billing” for additional edits. For Stillmotion, this makes the client aware and encourages them “to get all their thoughts down and make all their changes.” By putting it in the contract, then there are no surprises between you and the client.

Furthermore, Patrick explains that in most cases, “Nine times out of ten, if you tell somebody they have to pay a nominal fee of $500 for changes, they’ll walk away.” This tends to wash out the real suggestions from surface suggestions. “They just don’t understand the process and they don’t know how easy or hard it is,” Patrick says, “and that’s really on you as the studio to set the right expectations and process of how this communication is going to go and how we’re going to handle changes.” Again, this kind of material goes into a contract.

In addition, Patrick notes, there really “shouldn’t be a lot of changes because we’ve all looked at storyboards and we know exactly what it is we’re trying to do.” If you set the expectation that you make something and they think there’s room to “collect everybody’s thoughts and meet all of the requested changes”— that’s a beginner’s mistake. But by writing out the treatment, storyboards, and other expectations, and getting approval on them, then, Patrick explains, “we’re not even talking about changes because we’re going to operate on the assumption that you love it.” By setting that expectation in the production agreement, then there’s no expectation for significant changes. The other contracts in the Appendix provide a similar level of expectations for location, performers, and independent contractors.

Music Rights

An additional legal element to think about is the use of music. Most production house projects use some form of music. Not every moment of a project needs music, and I feel that it should be used judiciously and in support of emotional shifts in the story. There are five ways to source music:

- Original compositions from yourself, friends, or even approaching a local band—but be sure to get the proper rights in writing. Payment will be negotiable, but be sure the rights are perpetual.

- Sound libraries in music editing software (usually not that interesting), but may be useful for certain sound effects or moments.

- Track down the rights holder to a song you like (usually the publisher). For example, I wanted selections from several songs from Michael Stearns, who has done sound tracks to some Omnimax films (such as Chronos). I was directed to his lawyer and then I negotiated the rights for film festival use and paid a fee of $700.

- Creative Commons (https://creativecommons.org/). This is where you may find free music. Each song will show the types of rights it offers. For example, you may be allowed to use some songs for free—but only for noncommercial purposes, so be sure to understand the legal code, which is located at:

- https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/legalcode

- A short “readable” version is located here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/

- Websites that offer Creative Commons music are listed on their site, here: https://creativecommons.org/music-communities. They include SoundCloud.com, FreeMusicArchive.org, CCMixter.org, among others.

- A music licensing site, such as MarmosetMusic.com, MusicBed.com, Sound Reef.com, among several others. These usually include a database where you can search for moods and/or genres of music. You can select the usage and determine the fee.

Insurance

Another piece of legal concern is insurance. One of the key ways you can distinguish yourself from the amateur is to get insurance—it’ll make you come across as a pro. Moreover, you’ll be protecting yourself and your investment, and most importantly, covering any liability (including third-party damage, passerby, talent) in addition to covering your equipment. You may have your equipment covered through renter’s insurance or a homeowner’s insurance, but once you’re running a business you’ll need different coverage. Don Pickard of Tom C. Pickard & Co. in Hermosa Beach, California, says that when you’re shifting from “that personal status to the commercial, business status, a homeowner’s or a renter’s policy is either going to exclude it completely or give very, very little coverage.”

Even if you start a production company without owning any of your own gear and decide to rent equipment as you need it, you still need insurance. “The very first instance where that person has to go rent camera equipment they are going to walk in and immediately the person behind the counter is going to ask for their certificate of insurance,” Don explains. He says that even if you enter someone’s property or even try to get a permit to shoot on public property, they may ask for evidence of insurance because of the key need to cover any liability for damages to someone else’s property and any possible injury to your talent, crew, or passerby. This is why places you shoot (a business, a public place, venues, and so forth) require proof of insurance—they don’t want to be held liable for your project, so you need the coverage to protect them and yourself. Without that protection, you could get sued and depending on the circumstances, potentially lose your business.

Understand your legal rights when it comes to permits. Shooting in a public space, for example, may be supported as a right, especially if you’re shooting solo or with a small crew. It’s not recommended that you shoot without a permit, but at the same time you should understand what you can get away with, legally. Some filmmakers shoot guerilla style, not worrying about getting permits. For example, as a journalist or freelance journalist, you’re allowed to shoot material in public spaces, but if you have a large crew and are impeding traffic (pedestrian or street traffic), you’ll need a permit. There are resources such as the website, Lawyers for the Creative Arts (http://www.law-arts.org/) and the advocacy page of the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA) (https://nppa.org/page/advocacy), which offer information, for example about drone use. Municipalities and the federal government (such as the National Park Service) have clamped down on photography and video use, including some bans at different locations and increases in the price of permits. Being aware of these costs and your rights is key in understanding what you will need to do to work on certain projects.

Don feels that there are three elements to think about when considering the motivations for getting insurance as a production company:

- Protection for your own personal equipment.

- Protection for rental equipment. Even if you have your own gear, you may need more equipment for a particular shoot. Maybe you realize, “‘Oh, shoot, I don’t have the right grip equipment, I don’t have enough power packs, I don’t have enough back drops,’” Don says, “and they go to rent that equipment, then boom, they are faced with having to get insurance.”

- Protection for your own financial interest, which is covered by liability. On another note, this liability also protects locations and by extension, your clients. Most places won’t give you permission to shoot in their location unless you have liability insurance, because they don’t want to be in a position where they get sued and your production isn’t covered. It also protects your clients. Your company is doing the work and you’re responsible for the actions of your crew and talent. You’re liable, so make sure you have liability insurance.

Choose whichever insurance company best suits your needs. Shane Hurlbut’s company uses Insurance West (http://insurancewest.com/spectra.html), and Lydia Hurlbut says this is because they have garnered a strong reputation as well as offering outstanding service for them.

Below, I lay out the step-by-step process for getting a quote from TCP Insurance Agency. These steps are similar to those you would encounter in any insurance process, and I choose to use this company as an example since it covers startup production companies and offers online quotes. As Don explains, “I actually developed an insurance program specifically for a person who is just starting out. Yes, we insure the largest companies but also we insure the guy that is just starting out. Literally in under two minutes they can get a four-page insurance proposal just by typing in a few things. So to find out what their cost is going to be for the year is really, really simple.” From there, an agent can refine the quote based on the questions and needs of their clients. “That is when our people advise and help them along in this process,” Don says.

In addition to a standard insurance package, Don says there are other aspects they can cover, such as “hiring assistants, or talent, which is a workers’ comp exposure. You can get into stock photography or stock video or distribution and that is an errors and omissions conversation. And no two production companies or people are exactly the same. I mean they might be in fashion, they might be in advertising, they might be web-streaming, they might be music video. You know there are a lot of people doing drone work right now. Everyone has their own nuance that affects how their insurance coverage is written for them or not written for them. There is really no blanket statement that says, one size fits all. It’s all very individualized.” Filling out the online form is the first step in finding the kind of coverage you may need.

At the very least, you’ll have an online quote in minutes. Below, I will also go through the big picture, but not every detail, of the quote, as well as the other forms required to submit an application after getting a quote, including the video coverage checklist, equipment list, an online application, and an annual certificate processing fee of $350 (which will be rolled into the cost of the annual premium).

The video and film section of TCP Insurance (http://www.tcpinsurance.com/hd-film-video/) presents a brief introduction, explaining what they can provide for services, including general liability (important in covering negligence while on production), certificates of insurance (which you will need to rent gear and prove to clients that you’re covered, such as shooting on location in a public or private space), coverage of your own gear or equipment you rent, errors and omissions insurance (for coverage of material that is put under distribution or broadcast), and workers’ compensation (for coverage of employees, work for hire, and talent). This will be similar to any other insurance company quote.

- Click on “Video & Still Production” to go to the quote request page. This quote will tell you how much your insurance will cost per year, but it does not include workers’ compensation if you want to cover talent, for example, nor does it cover errors and omissions (for distribution and broadcast of your work).

- Video & Still Production Quote. Fill in all required fields and then submit.

- Ideally, you’ll complete this after you’ve completed your LLC forms and have your LLC accepted. Put in your name, address, phone number, company website, email, the value of your gear, and the estimate of your business income (likely to be the $0–$75,000 category). Submit and you’ll receive an email summarizing your quote and listing required forms to fill out before purchasing the insurance. My quote comes to $1,704 per year (which means I will need to budget $142 per month into my costs of doing business, covered in Chapter 5)—which is reasonable based on the coverage and protection the insurance provides. The required forms include:

- Equipment Schedule

- Online Application

- Insurance Checklist

- TCP Certificate Processing Fee.

- Equipment Schedule. List your gear, describe it, including serial numbers, and lay out the replacement cost for a new one. Include all the gear, and be sure to update your insurance agent right away when you get a new piece of gear.

-

Online Application. Fill out all of the required fields, including your name, your LLC name, address, phone number, email, and business website. If you’re living in an apartment, don’t worry about the premise or premise type unless your agent requires this.

The next section covers the type of work you do or plan to do. I include video production and postproduction (since I do post on my clients’ work), listing it as a 50–50 split. If I’m doing more post work, then I would increase the percentage.

They also want to know if you do any specialty work, such as stunts, music videos, drone work, and so forth. I choose none, since I don’t plan to engage in anything on the list.

The company also wants you to write a brief summary of the types of work or projects you do, such as weddings, commercials, promotional projects, and so forth.

The next section is a straightforward set of questions that you should just fill out and answer the rest of the Yes or No questions.

-

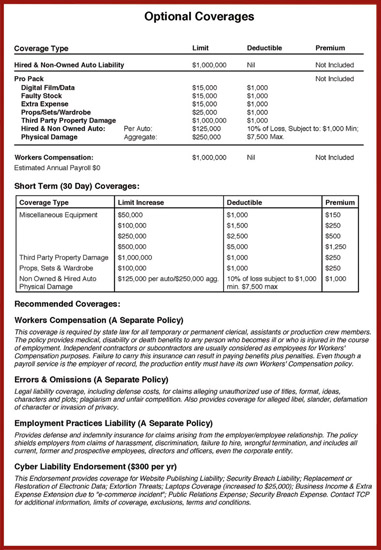

Video Coverage Checklist. This summarizes insurance coverages that are included or coverages you’ve selected not to purchase at this time, such as props, workers’ compensation, and so forth. These items may be added at anytime during the policy period. The “Pro Pack” includes material you may or may not want. Discuss each item with your agent and how much additional coverage will cost. Each one covers a different element of production and your standard policy will cover your gear and provide liability. The digital film/data covers memory cards and data while faulty stock will cover defective cards.

Note that there is $10,000 coverage of props, sets, and wardrobes—if you need this, then talk to your agent. It’s not a bad idea to make sure third-party property damage is covered (especially if you’re shooting on location), so if you or your crew break something, then you’re covered.

Typically liability would cover this, but “unless an insurance broker under stands this coverage, most agents get this wrong,” Don explains. General Liability (GL) policies exclude “Property Under your Care, Custody or Control,” Don explains. For example, during a shoot in a home grip equipment is placed on an expensive rug and destroys it. A general liability policy would exclude this; however, third-party property damage may be added to cover such a loss. Don also recommends you ask questions of your agent.

For example, Don adds, “The section on additional coverage will increase your premium, but discuss the importance of each one of these with your agent. Workers’ compensation, for example, would cover your talent and people you hire as contract workers (such as a second shooter, PAs, hair and makeup etc.). When production companies purchase general liability and workers’ compensation together, 99 percent of workplace liabilities are covered.”

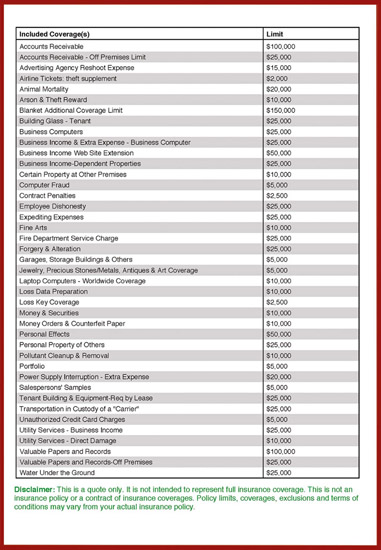

After going through theses steps (whether online, over the phone, or in person with an agent or company of your choice), you’ll receive a detailed quote. These steps may vary a bit from company to company, but are a form of communication and understanding of your insurance needs. I’ve include the quote I received from TCP, below (Figures 3.1–3.3).

Notice the liability coverage of $2,000,000 with no deductibles. If you had damages on a shoot and you were sued, you’re covered for up to $2,000,000 for any one occurrence with $4,000,000 for all general liability claims during the policy period. Don said the largest general liability claim he’s seen in 30 years was for $450,000. Don’t limit the need, however. Keeping it high is important.

If you plan to rent equipment for a specific production, such as a Phantom camera for slow-motion shots, then you can purchase rental coverage for 30 days at a time. For example, you can have a high-end camera covered for up to $100,000 for a cost of $250 for that 30-day period (this will have a $1,500 deductible if you did indeed damage it). If you’re hired to do an expensive production, which includes a set, props, and wardrobe that is high budget, then you can get coverage of up to $100,000 for $250 for a 30-day period (with a $1,000 deductible). Talk to an agent about each one of these and weigh the costs in the context of your production needs. The rule is, you’re better off paying for the protection than not. Roll the insurance expenses into your production budget.

This page also includes optional policies, such as workers’ compensation, errors and omissions, employment practices liability (if you have people you’ve hired and you face a sexual harassment suit, for example), and a cyber liability endorsement (which gives you up to $25,000 on a high-end laptop or several laptops, for example, as well as data protection, among other types of online protection). Take a close look at each of these and discuss them with an agent.

In any case, your client will want you to have the protection to cover the production. You don’t want to face a situation where you don’t have the coverage and you lose your business because you didn’t have the necessary protection. Don’t skimp on your insurance needs, even for low-budget productions.

Figure 3.1 The first page of the quote lists the estimated annual premium as $1,704. (Courtesy of TCP.)

Figure 3.2 The second page allows for optional coverage, including Pro Pack items, such as coverage of film stock, props/sets/wardrobe. You may not need or want any of these items—each one you add will increase your premium, so be sure to talk to your agent about the need for each based on your production parameters. (Courtesy of TCP.)

Figure 3.3 The third page of your quote lists all of the included coverage. If you’re not sure what any of these are, discuss them with your agent. Is there anything missing? If so, you may be able to add it. (Courtesy of TCP.)

The included coverage page lists additional areas the policy will cover. You may want to discuss this in detail with your agent, so you understand how each works. For example, Don explains that the Advertising Agency Reshoot Expense “applies to a direct physical loss to photographer/video operations. For example, a camera is damaged or stolen on set, or a power pack is dropped and damaged, the Ad Agency goes and rents additional equipment. If the image did not come out due to damaged lens or the production couldn’t get shot as a camera was stolen, or lighting was off due to a damaged power pack, then a re-shoot is needed—and this covers the production up to an additional $15,000 to complete the re-shoot.”

Gear Rental Companies and Insurance

Many rental companies are based in large cities, but there are now several companies that allow you to search and rent gear online, which is then shipped directly to you. Most of them will offer damage waiver policies (their own limited insurance), but owning your own insurance will protect you better than most rental companies’ policies. Here’s a quick overview of some of these web companies and what their rental policies require when checking out gear:

Table 3.1 Insurance Policy for Gear Rental Companies

| Name of company | Production insurance requirement | Damage waiver | Cover loss or stolen gear |

|

|

|||

| http://borrowlenses.com | No (except on expensive gear) | Yes, for unintentional damage to main item only, not lens caps, for example, and no water or sand damage or intentional damage. | No |

|

|

|||

| http://lensrentals.com | No (except on expensive gear or a high volume of inexpensive gear that adds up to a high cost) | Yes, but it does not cover “theft, water damage, intentional damage, or any other situations which leave you unable to return the items you rented.” | No on the standard plan. However, their optional Lenscap+ plan covers theft and loss of items with a 10% deductible. |

|

|

|||

| http://thelensdepot.com | No | Yes, but it does not cover “loss, theft, negligence in return packaging or any type of liquid or sand damage. Lens hoods, filters, chargers, cables, missing pieces, and other accessories are also not covered.” | No |

|

|

|||

| https://lensprotogo.com | No | Yes, responsible for paying 10% of value of equipment should damage occur during the rental period. The optional protection plan does NOT cover complete loss, theft or water damage. | No |

|

|

|||

| http://cameralensrentals.com/ | No | No. Customer is fully responsible for repair or replacement retail value of items. | No |

As can be seen, due to the limited nature of their coverage, it is important that you have your own coverage to better protect the gear.

Working from a Coffee Shop

A brick-and-mortar office tends to lend legitimacy to a business, but in the age of multistage communication channels through mobile devices, you really don’t need it. Meetings can be scheduled in coffee shops and restaurants. If you’re working from home, you can write off a percentage of your rent or mortgage, since a part of your dwelling is being used for your business.

Charles at Zandrak pursued a client by researching a list of startup companies that were building apps for smart phones. “We found that startups have a really great openness to new styles of promotion, because they are just trying to do whatever they can to get into the world,” Andrew says. While he found that it is more difficult to break down the wall of traditions of how to approach production storytelling with big businesses that have been doing the same thing for decades, with a startup “it’s very much they’re just building the foundation, they’re at a point where they’re more open to newer forms and more current forms of advertisement because they can start fresh.” David found Moodsnap (see Chapter 9), and Charles emailed the owner, David Blutenthal, “out of the blue, a coldcalling email from his contact form on his website. I pretty much told him that I had connected deeply with what he was creating, I thought that images and music being tied together and finding playlists based on emotionally driven choices is something that is really beautiful and something we exercise as a company.” He mentioned that their “philosophies were really in line and that I think it would be worth it just meeting up and chatting.” Andrew sent the potential client a link to their best work and he agreed to meet. And this is the point: they didn’t meet in an office.

“Only get an office when you can pay the office rent four times over per month,” Andrew says. “Nobody cares if your office is out of your living room. It is about your presence and what your perceived values are. We could have met at a coffee shop and you would never have known that we didn’t have an office.” Because, he adds, “My goal is to build a relationship and build a connection.” Since the client was in Boston, it was convenient to meet locally. “I met up with him for pizza the next day. Super casual. We went out and we started chatting and immediately, it clicked and it made sense to him. And we both understood each others’ philosophies and that translated well into actually doing work together.” And it wasn’t “necessarily about a product or a project or how we are going to make money together, but just sharing that philosophy and being on the same page: It was just a really strong foundation for us moving forward as a collaborative group.”

You can work from home and meet clients at restaurants and coffee shops. And if you’re meeting for business, you can write off the meal (but not alcohol), but you can’t write off regular meals, unless you’re traveling. It’s about making a connection and building a relationship. If you can’t afford wireless right away, you can work a few hours at a coffee shop which has free wireless internet. (Although it’s recommended that you do get high-speed reliable internet. You’ll want it long term, especially when you’re uploading large files.)

This chapter has looked at the heart of your business—it’s the material that protects you, the people you work with, and your clients. All of this information is designed to give you the tools to get started, to take you down the path in setting up your business. When it comes to insurance and taxes seek out experts in the field. Don’t shortcut or shortchange this process.

Now that you have created a legitimate business, you need to make a website with presence and put up a strong portfolio example, so clients can understand your style and see that you do compelling work.