In the final chapter, we examine what it takes to put together your own personal project. Many people who freelance and/or create their own production house business got their training and start in filmmaking. There is usually a passion for telling stories—whether it’s a work of fiction or a documentary. Stories— when done well—move people. In no other time in the history of cinema is it easier to make your own film project due to the low cost of gear and the ability to engage in crowdfunding to raise money for low-budget films. Crowdfunding isn’t about making Hollywood blockbusters, but it does allow for the creation of personal projects that would rarely get made without it. At the same time, crowdfunding also builds a fan base for the film. Very few spec films get made in Hollywood. Harun Mehmedinovich—a graduate of the MFA program in film directing at the American Film Institute—tells me that the odds are better trying to win in a Las Vegas casino than getting your script produced in Hollywood.

Kickstarter.com, Indiegogo (https://www.indiegogo.com/explore/film), and Seed&Spark (seedandspark.com) are sites that allow filmmakers to raise money to help make their film.

Seed&Spark Case Study with Keep the Change

Emily Best, the founder of Seed&Spark, argues against the idea that crowdfunding should be a way to fund a dabbler in filmmaking. She wants to fund filmmakers who need and want to make a living at doing what they love. It’s a curated site, so you are expected to have your team, vision, budget, and so forth buttoned up. Emily explains to me how Seed&Spark was designed:

To help filmmakers build meaningful businesses out of their films, giving them an infrastructure that would allow them the access and control to make a sustainable living. I want to get away from the dichotomy of “for money vs. for passion” to say that you can make money in something you’re passionate about. I don’t view crowdfunding as the outlet for dabblers, at least not how we’re framing it. We want people who consider themselves independent filmmakers to be able to pay their rent, feed their families, and grow their lives doing what they love for a living.

Seed&Spark bases its principles on the idea that most anyone can make a film with the right talent and perseverance, but to get your film watched—that’s an entirely different story. Crowdfunding helps a filmmaker to build an audience. If you use Seed&Spark to crowdfund your film, they will require you to lay out such basic information as:

- Logline

- Short synopsis

- Long synopsis

- ”About your team” description

- Artistic statement

- Budget information

- Production status

- Distribution plan.

They require a pitch video and remind people how the first fifteen seconds “should feel like it’s in the world of your film,” then shift into the personal appeal of what you need to make your film happen. They recommend that you should be sure to “make your crowd feel there is a sense of inevitability that a great project will result.” Don’t be a defeatist! Build incentives into the campaign, so that the funder feels like they’re getting something special and unique. They recommend that the key incentives for a project are $10–25, since you’ll get a larger amount of people chip in a little bit. They recommend that these incentives be “personal, visual, and sharable on social media,” because if one person shares, dozens of others will see how one person shared and got something “cool,” and they’re be more inclined to jump on board.

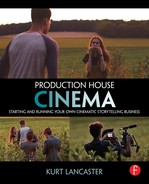

One of the components that makes Seed&Spark stand out is their unique wish list—it’s like a wedding registry, where your crowdfunding team can choose what they’re buying for you (from batteries to a camera rental) with a brief description of why you need it.

Here’s an example of some of the approaches found in a successful crowdfunded romantic comedy, Keep the Change by Rachel Israel, which raised over $50,000 with support from 533 people. It began as a sixteen-minute short that screened at several festivals, and helped inspire the desire to create a low-budget feature film. See: http://www.seedandspark.com/studio/keep-change.

Logline: “A young man struggling to hide his autism falls in love with a young woman who challenges his desire to appear ‘normal.’”

Budget incentives of $5 and $20 (among higher end incentives), see Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1 Notice the unique incentives for this film and how they reflect the nature of the film (romantic comedy).

(Courtesy of Seed&Spark.)

As you skim through their page, take note of how each incentive is unique and reflects the talents of the people they have on their team. A $1,500 or more investment, for example, would purchase a Broadway music CD “mixed by one of our main cast, music blogger – William S. Deaver”; or an Ice Box Cake by main cast member, “Nicky Gottlieb (Travis McHenry) – hand delivered by Nicky and director Rachel Israel (limited to NYC locals)”; or an “original painting by supporting cast member Amy Rosenfeld (Playing wonderful relentless Annie).” And it shows images of the five paintings (the gift is limited to five).

The wish list includes everything from hard drives, lighting, location sound, insurance, location fees, casting, vehicles, catering, legal services, among others. You can purchase units of a product or loan an item out.

Figure 10.2 The first few items on the production wish list include a specific brand of hard drive, lighting, and props.

Notice how a potential funder is not purchasing $2,000 worth of hard drives, for example, but is putting $25 towards the hard drive (or more if they purchase more than one unit of payment). (Courtesy of Seed&Spark.)

Crowdfunding campaigns allow those with a vision, to get their film made. Another approach to funding includes branding, especially if you’re making a short. Andrew Hutcheson of Zandrak Productions feels that it’s important that filmmakers—especially those who are working the daily grind of a production house—“stay creatively fulfilled and stimulated.” He believes a good way to fund a short film is to find a brand to put into the film. “There is where your money comes in. And if you are going to raise money, use the same principles you have towards your business. Appeal to someone’s emotions,” he explains. At the same time, Andrew says it’s important to think about your potential audience. “Is there an audience for this movie? Is someone going to want to see this? Why are they going to see it? Why am I making it? What am I making?”

Andrew, like Emily Best, believes that you’re not just funding a passion project to make a film, but a business:

If you are going to make a feature film, then you have to make it for the idea that it is a profitable venture. If you are going to make a short film probably don’t try and get someone to pay for it. Maybe make a short film that’s going to be part of a brand—they are just going to put this out there. And don’t be dissuaded if you really want to do a short film that Bose can sponsor if you put in their headphones. But what if they say they don’t want your film? Is Bose the only company that makes headphones? Call all of the headphone companies. It is a numbers game. And if you are willing to take the rejection, you will find the person that’s right for you. You won’t find them on your first try or your tenth. But if you keep calling and trying and keep learning what works and what doesn’t and who’s right for you, you might find the right person.

To help build support and a network, Andrew recommends that you “look into the film commission, all of the competitors. This will give you a list of all other filmmakers, either to collaborate or donate to your crowdfunding campaign.”

Kickstarter Case Study with Frame by Frame

If the popularity of film schools is an indicator, a lot of people want to become a filmmaker. Alexandria Bombach graduated from Fort Lewis College1 in Durango, Colorado in 2008—just as the Great Recession was about to begin. Her dream was to make films. She got rid of everything she had, bought a 23-foot 1970 Airstream camper, and with two friends, traveled through Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and California “to search for the stories of people who have turned their backs on the creature comforts of society to live in school buses, vans, and other small spaces.” In order to live her dream as a filmmaker—to fund her passion and not look back—she’s been living on the road for the past six years.

Alexandria learned the basics of filmmaking in college (she was a business major), but it was an internship at Osprey Packs that gave her the opportunity to apply her filmmaking skills to a series of creative promotional films and allowed her to hone her storytelling skills (these works can be seen at http://redreelvideo.com/gallery). “It was so many shorts in a very short amount of time,” she explains, “so it was kind of just like a crash course in shooting and getting story out of a very limited budget.” These projects would eventually lead to a series of beautifully shot short documentary stories sponsored by Osprey Packs (along with Horny Toad Clothing and Clif Bar) that told stories of those who engaged in creating positive change in the world (see http://www.moveshake.org/).

But it didn’t begin easily. Alexandria tells me that she was glad the recession happened. It forced her to become a filmmaker. “I started a production company right in the middle of the recession,” she says. “I quit my waitressing job. I was really glad the recession happened, because if I’m not going to make money anywhere I might as well do exactly what I love.” She did apply for jobs, but got nothing. “I’m not getting any jobs so I’m just going to make my own thing and that was the best thing that could have happened, because just walking up to companies and asking them to give you a job doesn’t work.” She actually discovered that by “making your own thing, making your own style—and doing it well, then companies come to you!”

Alexandria ended up naming her company, Red Reel. “It was really super desperate times. I was not feeding myself very well, we were very worried about rent, I was living in Chattanooga, Tennessee. I just called it Red Reel and I had no idea if it would last. And I didn’t really have anyone telling me that it was possible.”

With these projects under her belt, among other promotional film projects she worked on, Alexandria was ready to take on a new challenge—to shoot a documentary about photographers in Afghanistan. She had helped edit a friend’s short film that included footage from Afghanistan, and once she saw the footage she wanted to go and capture that beauty herself. She explains how she’d never been to Afghanistan but, she says, “as I started seeing the footage of the b-roll, of people walking down the street in normal everyday life, it made me question my own perception of what I thought I knew about Afghanistan.” It made her want to go and make her own discoveries. The project began initially in the fall of 2012 as a short. Alexandria, along with Mo Scarpelli (who worked with her on several other projects), was intrigued about telling the story of local photographers.

Alexandria used all of her savings and sold her car to get plane tickets to Afghanistan, but after shooting in October 2012, Alexandria went home and started editing the film and realized the project was larger than anticipated. She explained how she had been “making shorts for a while and I believe that’s a really great way to get stuff out there, but when I got back and I was looking through the interviews and the footage we had, I just really felt that this was a more compelling film than can fit into a short. I remember crying into my laptop, actually. ‘Oh no, this is a feature!’” At that point, she had to make a decision, “because it’s a whole other cliff to jump off of.” She had to budget out the entire project and plan for what they needed to make the feature documentary happen. “This film would never have happened without Kickstarter,” she explains. “As a first time filmmaker it’s really hard to get grants.”

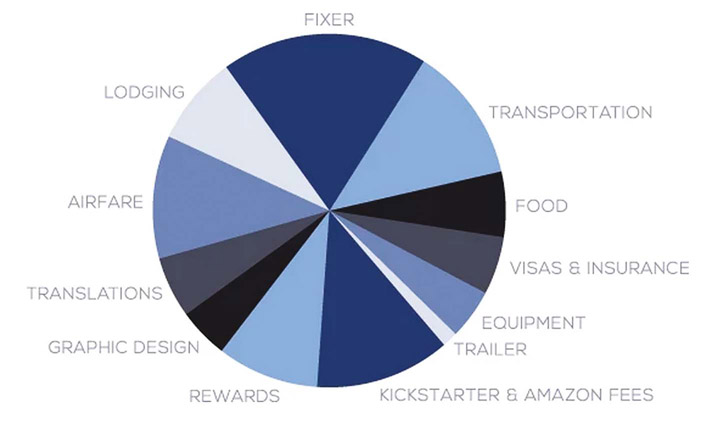

In order to make a feature-length documentary film, they had to go back and spend more time there in order to capture the larger stories. It was important to Alexandria that the project remain an independent film—where they retain full control of the content and story, so they didn’t ask for film funding through a traditional route. Alexandria had successfully raised just under $10,000 for her first independent short film, 23 Feet, but this time she would need $40,000 to fund the two-month trip. The Kickstarter campaign ran for one month from July 29, 2013 to August 28, 2013. “I think we got $20,000 in the first couple of days,” she explains, “and then there was kind of a lull and it was kind of scary. We made our goal and there were three days left and then Upworthy posted our trailer—then it went up like $30,000 in about three days.” They ended up raising over $70,000 for Frame by Frame.

Kickstarter Tip by Alexandria Bombach

It’s nerve-racking asking people for money. But you just have to get past that. We had to do a lot of defining what the project was. Which was really hard because although we had been there and shot, we didn’t want to define exactly what the film was going to be because we still wanted to shoot for two months. And so that was really tricky. Also just a lot of figuring out math. You know we can offer this reward at this price but it’s going to have this much in shipping and how will this affect our distribution? Planning the DVD coming out before our first screen day was not a good idea, since that would impact any distribution plans.

I think the hardest part about Kickstarter with films is trying to have a lot of foresight into making the right decisions. I did one Kickstarter for 23 Feet for the tour that I did and that was successful on a much smaller scale, but it helped me a lot. When people come and ask me for help with Kickstarter, I’m always telling them, just sign up and start backing things. You’ll start learning so much. Just being a part of it at least once is really helpful.

A lot of the campaigning was behind the scenes. Emailing people, and people who are friends and influencers and asking them to be a part of the team to get the film out there. We were really lucky to have some really great people who said, “Yeah, I’m going to champion this with my connections,” and they donated right away. Their priority was to share with their community. And that’s a very powerful thing, since it wasn’t just coming from us. So a lot of it was emails—even more than Facebook and Twitter. But it was also setting everything up on the page, such as finding the title of the film and making the trailer before the film is done.

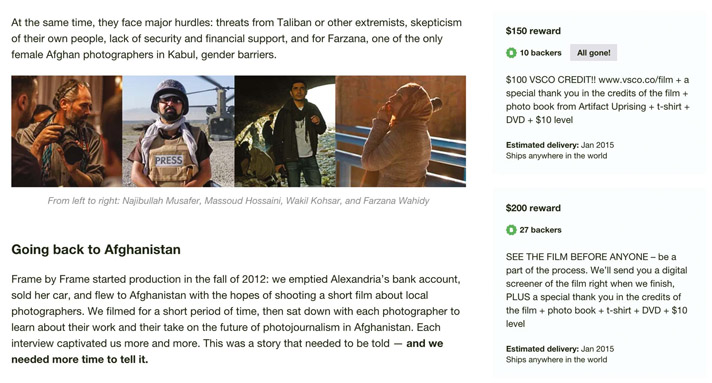

The story revolves around four Afghan photojournalists in post-Taliban Afghanistan. When the Taliban were in charge, it was illegal to take pictures. The four characters in the film include Najibullah Musafar, who teaches photography and feels the country’s identity is at stake. Wakil Kohsar examines the heroin addicts on the streets and in recovery centers. Massoud Hossaini earned a Pulitizer Prize for Breaking News Photography in 2012 for his image of a bombing during a religious procession. Hossaini’s wife, Farzana Wahidy, is also a photographer who examines the women of Afghanistan—especially the lack of education among women due to the Taliban’s strict policy against educating them. (See Figure 10.3.)

The film debuted at the South by Southwest (SXSW) festival. Sheri Linden, writing a review for The Hollywood Reporter, noted how the film is “as artful and empathetic as its subjects’ work . . . Frame by Frame is a work of profound immediacy, in sync with the photographers’ commitment and hope” (March 14, 2015). It would go on to screen at film festivals in Atlanta, Cleveland, Ashland, Dallas, Nashville, Berkshire, New Zealand, and at Hot Docs, among others.

Figure 10.3 The four subjects of Frame by Frame: Najibullah Musafer, Massoud Hossaini, Wakil Kohsar, and Farzana Wahidy. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

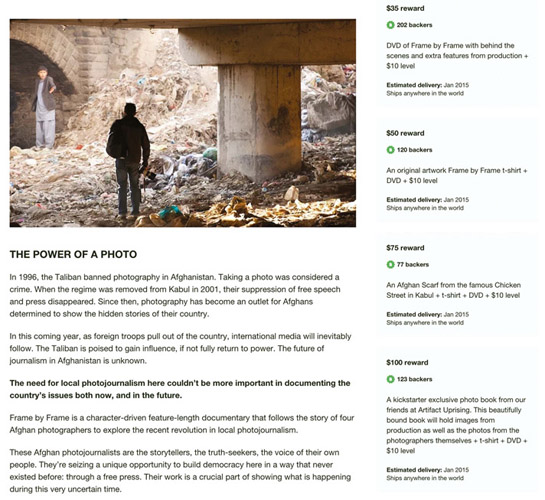

Figure 10.4 A girl smiles in the Kickstarter preview of Frame by Frame. Capturing the sense of hope was one of the elements Mo and Alexandria wanted to show in their documentary. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

Figure 10.5 Alexandria Bombach on location in Afghanistan as she shoots with a Canon 5D Mark III. Along with Mo Scarpelli, they raised over $70,000 to fund their documentary, Frame by Frame. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

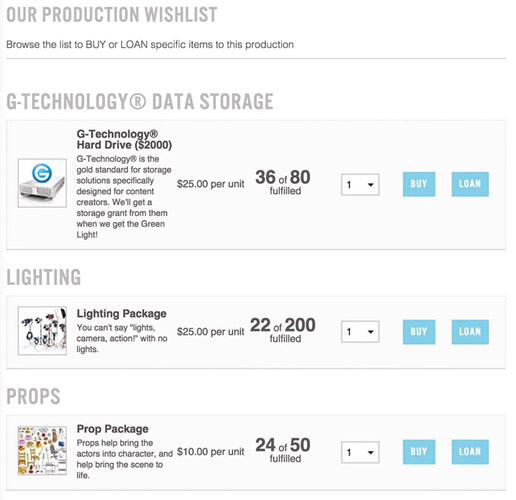

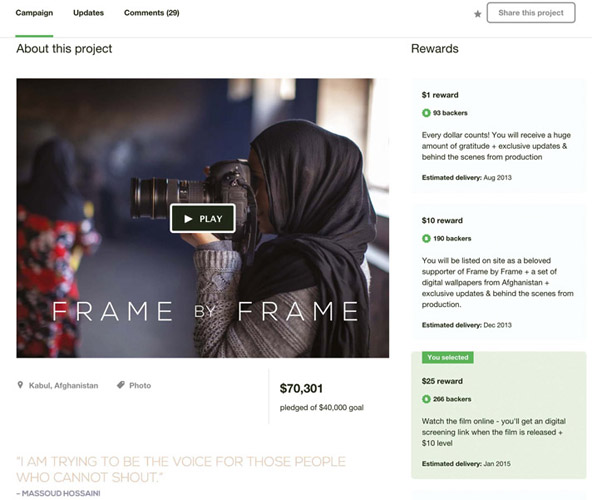

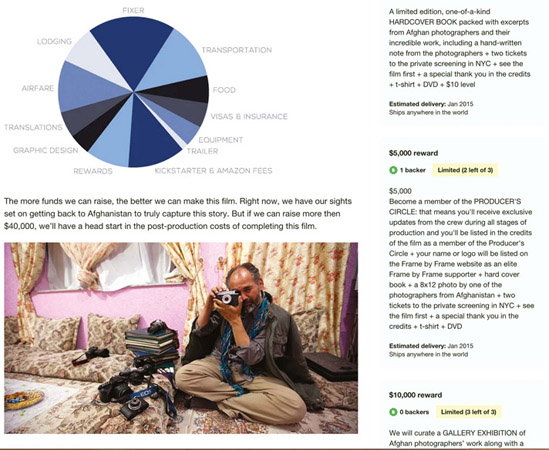

Initially, they needed $40,000 to travel and shoot the project, but they ended up raising $70,000, which covered their postproduction expenses. The budget breakdown looks like this (Figure 10.6):

Figure 10.6 The budget breakdown of Frame by Frame’s Kickstarter campaign. The fixer is their local contact, guide, and translator in Afghanistan. Notice that the initial budget did not include postproduction work. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

A Kickstarter campaign involves a lot of planning and vision. It’s not something to be done lightly. Here’s the campaign page to Frame by Frame. I’ll break it down in sections and discuss them in more detail.

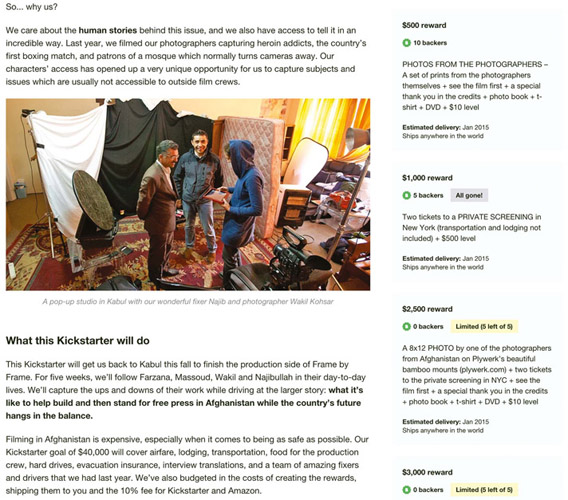

The filmmakers directly address why they’re the best people for the project. They describe how they have already gone to Afghanistan and met the characters for their story: “Last year, we filmed our photographers capturing heroin addicts, the country’s first boxing match, and patrons of a mosque which normally turns cameras away,” they write. They also describe what the Kickstarter campaign will fund. First, they describe the importance of the story: “What it’s like to help build and then stand for free press in Afghanistan while the country’s future hangs in the balance.” That contains a core conflict and reveals what’s at stake for the characters. There’s potential drama that will help make it a compelling film.

Figure 10.7 The opening section of the campaign page contains the beginning of the rewards: $1, $10, $25. It also shows the amount of money raised and needed, a strong image from the film, and the trailer of the film, including an appeal by both Alexandria and Mo. The trailer for a film project is the most important tool you have in raising money. It shows what you can do and the potential of the story. Over $16,000 was raised from backers contributing $35 or less. Making sure a backer can get a film (whether a digital copy or DVD) is important at these lower-priced levels, Alexandria says. She’s noticed that many failed campaigns don’t provide a copy of the film unless backers pay $50 or more. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

In addition, they cover the cost of making the film itself, including the costs of the rewards:

Filming in Afghanistan is expensive, especially when it comes to being as safe as possible. Our Kickstarter goal of $40,000 will cover airfare, lodging, transportation, food for the production crew, hard drives, evacuation insurance, interview translations, and a team of amazing fixers and drivers that we had last year. We’ve also budgeted in the costs of creating the rewards, shipping them to you and the 10% fee for Kickstarter and Amazon.

They make a case for what the $40,000 budget will cover, but they also make a plea for additional funds—if they raise more than their budget, it will provide

Figure 10.8 Here the filmmakers provide background on photography in Afghanistan—how it was illegal during the Taliban era. In addition, they make a plea for the need to support photojournalism in Afghanistan and how their documentary will help tell that story. Also note that about $18,000 was raised from the $50–100 reward categories—which includes a t-shirt, Afghan scarf, and photo book as the prices increase. Be clear that as you add these rewards they have to be paid for out of the money raised. Nearly $34,000— 85 percent of their goal of their $40,000—was raised from the $100 and less categories. Kickstarter—all crowdfunding sites—rely on a lot of people giving a little bit of money. Don’t rely on a few giving a lot of money. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

Figures 10.9 and 10.10 The filmmakers discuss how they’ve already been to Afghanistan once and received open access from photojournalists—the access to their characters “opened up a very unique opportunity for us to capture subjects and issues which are usually not accessible to outside film crews,” they write. This inside access assures supporters that they’ll be getting a unique film and telling a story rarely—if ever— seen in the Western press. Indeed, it is such stories that attracted Alexandria to the project. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

Figure 10.11 The budget pie chart. They also include a still from the trailer. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

Figure 10.12 A description of the rewards. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

a headstart on the postproduction process. Also note the higher level rewards. There are a couple of mid-level rewards of $150 to $200, but then there are several categories from $500 to $10,000. The mid-level rewards raised nearly $7,000. Very few backers supported the high-level rewards. One backed the $5,000 reward, while five supported the $1,000 reward, and ten put in for the $500 reward—which did provide an additional $11,000. Thus the mid- to high-level categories ended up raising an additional $18,000.

The mark of a successful campaign, Alexandria says, involves hard work and treating the campaign as a full-time job. Some people just launch the campaign and hope it’ll take care of itself, but it requires constant attention. Failed campaigns are a hard thing for a filmmaker to accept, but they happen. With Kickstarter, there are rewards—the incentives provide a sense that a donor will receive something tangible from the campaign. Alexandria says, “When you have a film, the first obvious thing that you’re going to want as a reward is to see the film.” Setting the right price for that access is key. “Sometimes I’ll go on people’s film campaign pages, and the first price-point to see the film is set at $45—that’s ridiculous. You should never have to pay that much to see a film. It’s like a preorder of a film and the most that should be is $35, but even that is pretty high.” Frame by Frame’s Kickstarter campaign allowed donors to receive a digital copy of the film for $25.

Kickstarter campaigns also fail when filmmakers don’t prepare enough beforehand, Alexandria notes. “I was working on Kickstarter for at least two months before it even started and it was just Mo and me.” They also got a team together to make the trailer as strong as possible. “We had people work on the sound of the trailer and the color of the trailer on a deferred payment,” she explains. “If we made money through the Kickstarter campaign, they would be placed in the budget to get paid. They were taking that risk with us, but people believed in the project so that was good. I think a lot of people who don’t succeed just think that Kickstarter is going to run itself.”

But to commit to that kind of business work—to plan, coordinate, decide the rewards, engage in a social media campaign—can be difficult for creatives, Alexandria explains.

But it’s also the world we’re in right now. This isn’t Canada providing government funds for filmmakers. We have to raise this money ourselves. I’m really glad Kickstarter is there, but it’s not just the money. For us it was really crazy to have 1200 people say, ‘Yes I want to see this film!’ And they’re not just backing it, but they’re also sharing the campaign with the trailer, and more people become interested in it. It was heartening because we received a lot of great PR early on. And people are waiting for the film while you are still in the early stages of production so it’s terrifying.

Figure 10.13 The filmmakers confront the reality of making a film and warn that supporters are funding the actual filming of the project—not the postproduction. However, since they did raise over $70,000, they were able to get additional equipment (Canon 5D Mark IIIs with some good lenses) in addition to covering some of their postproduction costs. (Courtesy of Alexandria Bombach.)

Part of the planning was also making sure they did the story right. The most successful element of the trailer, Alexandria says, was in the importance of potential backers of the film seeing Afghans talking—“that was the biggest part of the film.” She explains, “This is going to be a story about Afghans. If it was just Mo and me up there—two white women saying we’re going to tell their story instead of them telling their story—I think it would have hurt us a lot. The trailer for any film needs to have some sort of visual component. It’s necessary.” And, she adds, “When you have a really beautiful place like Afghanistan, it helps. In our editing style we really wanted to show the beauty of the country. And we were lucky to have great access to our characters.”

Providing updates to backers is important. After getting the successful campaign funded in August 2013, they planned their trip and purchased gear, traveling to Afghanistan in October and returning in early December. By January 2014, Alexandria started editing and didn’t finish until a year later, then they hired a musician for the score (Patrick Jonsson). They also put together a team that included a couple of executive producers, several associate producers, a story architect, and a translator. The team of experienced documentary filmmakers would provide feedback that would get them to the final stages.

In the end, the success of their project stemmed from Alexandria and Mo’s filmmaking talent honed from doing production house work in a cinematic way over several years.