What specifically is the cinematic style? How is it different from some mainstream commercial work? I start here since the premise of the book hinges on an understanding and definition of the cinematic style, what it means, and how you can apply it to client-based work. I start by examining a couple of moments from a 60 Minutes piece and a promotional work in order to show the difference in style when a work is created from narration and a work created cinematically (using shots, voice, sound design, and editing for rhythm). In addition, I look at Stillmotion’s concept of the psychology of the lens—the importance of choosing the right lens for a shot, as well as charts defining and showing how different types of camera movement, shot sizes, angles, and lenses impact how audiences perceive the psychology of a scene. This is followed by a description of Stillmotion’s MUSE storytelling process. In short, I examine some of the tools of filmmakers in order to drive home the understanding needed to create cinematic-style client-based stories.

The Narration Style

Commercial narration and news narration are similar—they share a broadcast style that grew out of radio news broadcasts where words told stories through descriptions of action. News reels—some heavy with propaganda—during World War II perfected this style. Education films from the 1950s to the 1970s brought this style to film in public schools. Images were mainly used to illustrate what the narration—the omniscient “voice of God” style—told the viewer.1 Words told the story. Images illustrated the story like decorative wallpaper. Most commercials and television news follow this narration-driven style.2 In cinema, visuals (along with a compelling audio design) tell the story and words are frosting on the cake—take them away and you can still follow the emotional structure of the story through the shots and soundscape. Words, narration, and dialogue—when used cinematically—sweeten that visual and sonic structure.

To illustrate this style, I’ll look at a couple of moments from Lara Logan’s “The ascent of Alex Honnold”3 from CBS’s 60 Minutes. It tells the story of Alex’s insane free solo climbs that, in Logan’s words, sets the tone: “He scales walls higher than the Empire State building, and he does it without any ropes or protection” (Logan and Newton, 2011). I compare this work of journalism with a staged promotional film by Tyler Stableford, “Shattered,”4 which tells the story of another climber, Steve House, who looks like he is climbing ice without rope. Both of these projects offer compelling stories told in two different ways.

Perhaps comparing the two isn’t necessarily fair.5 This book isn’t really about journalism, but what I find interesting is how commercials and promotional shorts sometimes mimic the narration-based style of broadcast journalism (from shorts produced on The Weather Channel to 60 Minutes). Since Stableford’s brilliant promotional short is a great example of cinematic client-based work, I really like how it contrasts with the real news story. So why compare the two? Because the style of the broadcast news piece—heavy with narration that tells us what’s going on—is a stylistic choice, not a hard and fast rule in nonfiction work. And since it’s a choice in style, the audience will perceive the story differently than in a film produced in a cinematic style. The comparison and contrast works, because I’m focusing on how the respective stylistic choices between the two impact an audience differently.6

The key point I want to make is how different techniques work and impact audiences so that we can avoid what doesn’t work and apply what does work in order to improve our own projects and learn how to use the best tools to capture an audience’s attention. As Wes Pope, who teaches Multimedia Journalism at the University of Oregon, notes, different storytellers blend different approaches. He describes at least five styles of documentary storytelling alone: “journalistic, interview driven, cinema vérité, reenactment, and reflexive.” Production house producers should be aware of different styles (whether it’s from news, documentary, or fiction) and apply elements from these different styles in order to best shape the stories they need to tell for their clients. For example, both Stillmotion and Zandrak produced work that utilize fiction and documentary techniques, the former in a book promotion, the latter for an app commercial (both covered as case studies in Chapters 8 and 9). 60 Minutes could have chosen to emphasize more cinematic techniques and focus less on the omniscient narration style—but that’s what they do. In the process they lose some of the potential cinematic magic (and perhaps maintain journalistic integrity—but that stylistic argument is open to debate).

Cinematic Techniques

These are four major tools filmmakers use to help create cinematic experiences:

- Shots—the visuals—are designed to tell the story. There are a wide variety of shot sizes and camera angles used to create stories—from extreme wide shots to extreme close-ups. Many filmmakers provide coverage (shooting a range of shot sizes and camera angles in order to give the editor more choices in editing)—and make sure everything gets covered. Specific shots capture specific emotional moments, providing a visual storytelling palate for the editor. (If visuals don’t carry the story emotionally, then you get the wallpaper effect—shots used to decorate the words of a narrator, thus nearly any type of shot would do.) This also includes camera movement. (See the latter part of this chapter for a detailed examination of the psychological effects of camera angles, camera movement, and lenses.)

- Voices of characters. Characters are the ones who speak—not an omniscient “voice of God” narrator.

- Sound design. Ambient audio collected in the field or used from sound libraries—as well as using the right piece of music at the right time (the proper emotional shift occurring in a story)—helps immerse the audience into the world of the story. If there is little to no forethought or design of the sonic landscape of the film, then you’ve thrown away half of the resources of a filmmaker and lost one of the most powerful tools a filmmaker can use. (Check out Michael Ondaatje’s The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, Knopf, 2002 and the transom.org interview with Murch at: http://transom.org/2005/walter-murch/.) Studying both of these will prove a treasure-trove for those wanting to dig deeper into cinematic storytelling.

- Editing for pacing and rhythm. The editor’s job, says Karen Pearlman in her work Cutting Rhythms (Focal Press, 2009: 58), is to shape moments of tension and release in the audience by crafting “the rise and fall over time of intensity of energy.” There are many good books on editing, but this kernel of wisdom continues to echo as a universal principle for nearly all editing projects. This includes the shaping of audio and visuals in such a way that the audience is pulled into the world of the film and taken for a ride. Both visuals and the sonic landscape must be treated equally in the edit in order to pull off an effective experience for an audience.

Narration and Decorative Shots

If narration is used improperly—when it tells the story rather than helps enlighten the story—we begin to lose the power of cinematic techniques and we may fail to pull the audience into the story. An example of this occurs at 2:25–2:53, at the climax of Alex’s ascent in the 60 Minutes work, “The Ascent of Alex Honnold.” We hear Logan’s words as we see five shots, her voice is in italics (see Figures 1.1–1.5):

This is Alex in the film, Alone on the Wall. He’s done more than a thousand free-solo climbs, but none were tougher than this one. [This narration provides context and is ok.]

Figure 1.1 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

Here he is, just a speck on the northwest face of Half Dome: [We see this in the shot, so we don’t need someone to tell us about it.]

Figure 1.2 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

You can barely make out the Yosemite Valley Floor below, as he pauses to rest: [Again, the visuals—along with a strong sonic landscape—pull us into a story, while narration that tells us what we’re seeing and hearing pushes us out of a story.]

Figure 1.3 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

He’s the only person known to have free-soloed the northwest face of Half Dome. [Pan and tilt up for next two images]: [This narration provides context, so it is ok.]

Figure 1.4 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

Figure 1.5 Courtesy of 60 Minutes.

Overall, these shots are good—some are even strong—but their impact is lost in the narration.

In another segment, where Honnold is hanging on another cliff face, we hear this from Logan (see Figure 1.6): “Alex moves seamlessly across a section of flaky, unstable rock, pausing to dry a sweaty hand in his bag of chalk. There’s nothing but him, the wall, and the wind.” But all of this can be seen and heard, while the narration gets in the way of the cinematic possibilities of this moment. We hear breathing and some ambient wind but the audio mix doesn’t make it stand out, because it is lost in the voiceover. In addition, the cinematographer could have zoomed in to a close-up so we could see Honnold’s expression, visually driving home the moment. But the narration does it for us.

The cinematic impact of a close-up and a sound design has no priority. Instead, the producers chose to allow a narration to tell this part of the story. This is a stylistic choice and for those who want to engage in cinematic-style stories in production house work, it’s the wrong choice. The right choice would stem from this key question: What does it feel like to hang on the face of a cliff thousands of feet off the ground?

A cinematic approach would have forced the thinking about what kinds of visuals and audio are needed to answer this question. Perhaps this moment could have been told by the subject (through Honnold’s voice, rather than a narrator).

Notice that with this narration, it doesn’t matter what type of shot we see of Honnold. Any shot of him on the wall reaching into the chalk bag fulfills the requirement of decorating the narration—thus it’s called wallpaper.

Figure 1.6 Logan’s voice in “The Ascent of Alex Honnold” tells us what Alex does in a play-by-play style.

(Courtesy of 60 Minutes.)

By making the choice to engage in a voiceover narration style instead of a cinematic style, the emotional power of this scene fizzles. This same kind of mistake7 is made countless times in commercials and promotional shorts as well. For example, in a local 30-second commercial for Central Fresh Market we see in the second shot a woman holding a basket and an orange pepper as she looks at the camera and smiles, stating, “I shop here because the fresh meats, fruits, and vegetables make meal planning a breeze” (see https://youtu.be/n0uyaAgl-Hk and Figure 1.7). This is narration masquerading as dialogue and I include it as a warning. You may have characters speak with no narration, but if they’re selling a product in the dialogue—then it fails the cinematic test (and becomes the kind of stuff I muted out as a child and still avoid watching, today). We know when the cinematic style is working because shots and sounds, when rendered effectively, are designed to emotionally engage an audience and pull us into the universe of the film.

Figure 1.7 A commercial for Central Fresh Market engages in the broadcast style to sell its products. (Courtesy of Central Fresh Market.)

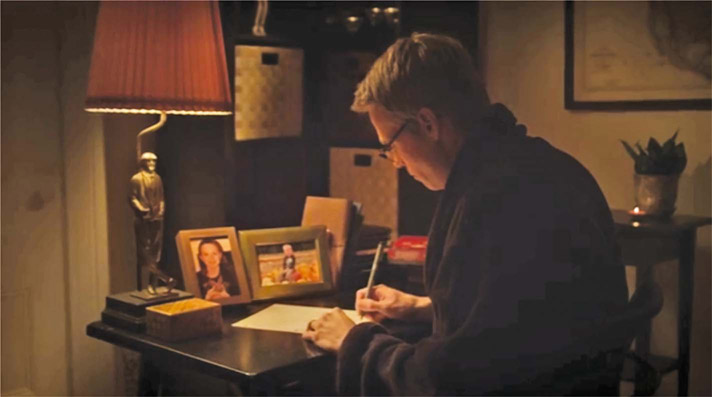

Is there a correct way to do narration? In Zandrak’s Hasbro commercial, “Growing in Pieces” (see http://www.zandrak.com/hasbro), mentioned in the Introduction, the voice of the father provides an authentic voice through the device of writing a letter to his son who is about to go off to college (see Figure 1.8). Yes, this is staged and a work of fiction, but the technique used here is one we can learn from.

Figure 1.8 The father writes a letter to his son in Zandrak’s Hasbro commercial, “Growing in Pieces,” providing us with an authentic voice that pulls us into the story. (Courtesy of Zandrak.)

I always say that narration should be used if it helps provide context for a story so the audience doesn’t get lost. Indeed, Werner Herzog, in Paul Cronin’s book, Werner Herzog: A Guide for the Perplexed (Faber & Faber, 2014: 117), describes how he uses narration in his documentaries: “I have the feeling my presence can give a film a certain authenticity, something you don’t necessarily get from listening to a well-trained actor with a polished voice. I realized there was value in me being the chronicler of events and presenting my own viewpoint on things.” Herzog’s documentary films tend to engage in multiple styles of storytelling, including a “mix of reflexive, cinema vérité, and interview styles,” says Wes Pope of the University of Oregon.

Creating Sonic Landscapes

Walter Murch, the only person to have earned an Academy Award for film editing and sound mixing, discusses a discovery he made while mixing audio for Francis Ford Coppola’s The Rain People (1969). He describes how a scene from the film takes place in a telephone booth near a highway. But when he added street noise to the scene, the voice of the actress (Shirley Knight) was lost when he brought the levels up to a volume where he could hear the traffic. He says, in Ondaatje’s The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film (Knopf, 2002: 244):

I discovered that if I used what you might call a precipitant sound, something we associate with a specific environment but that is itself distinct, then the other sounds come along automatically. What I did was record somebody dropping a wrench fifty feet away—as if fifty feet away from the booth, in the garage of the service station where the woman in the movie is stopped. It was important that it was far away, and that it was a certain kind of wrench dropping on a certain kind of polished concrete. If you’ve ever been in such an environment, you know what that sounds like and you know that such sounds are commonplace in service stops near big highways.

That little sound was able to bring along with it, imaginatively, all the traffic. But the traffic exists in your mind. I spent a lot of time trying to discover those key sounds that bring universes along with them.

He continues:

This metaphoric use of sound is one of the most flexible and productive means of opening up a conceptual gap into which the fertile imagination of the audience will reflexively rush, eager (even if unconsciously so) to complete circles that are only suggested, to answer questions that are only half-posed. What each person perceives on screen, then, will have entangled within it fragments of their own personal history, creating that paradoxical state of mass intimacy where—though the audience is being addressed as a whole—each individual feels the film is addressing things known only to him or her.

The first minute of Tyler Stableford’s “Shattered” expresses several shots of early dawn landscapes, a close-up of Steve House’s face—breath visible in the chilly air as he pauses and looks up at the early dawn sky. As he walks, we hear his boots crunching and squeaking against the crystalized snow.

When we hear House’s boots crunching on snow, it is a type of snow that is crystallized at a cold temperature (usually the single digits or teens on a Fahrenheit scale)—it is the type of snow I remember hearing in the cold winter growing up in Maine. And there’s really no reason why this type of sound design cannot be used in the narration-centered or omniscient-style work. It really requires less talking onscreen.

House’s breathing and the crystal crunch of snow becomes Murch’s falling wrench onto a polished concrete floor—the precipitant sound—that brings along with it the feeling of the cold, wind, and icy snow of House’s journey and it activates my imagination (my memories), helping to further authenticate and bring immediacy to House’s journey.

If sound design is lacking in your project, you’ve lost half of your film. Take the time to be as creative with your sound design as you are with shooting your images. As Pope notes, “Visuals and sound work together 50/50 to create scenes. Visuals stop being b-roll and start to carry the narrative.” If you want strong visuals, create a strong sound design. Conversely, if you create a weak sound design (or none at all), then your film will tend to express weak visuals (even when they look good). One of the failures of the 60 Minutes piece is the lack of a strong ambient sound design that would enhance the feeling of Honnold’s climb.

Editing for Rhythm Through Sound and Picture

Along with Stableford’s compelling shots and sound design, the rhythmic edit brings together these elements. In Stableford’s work, we see how his editor, Dave Wruck, takes the director’s shots and creates an emotional and physical rhythm around energetic cuts at the climax, while the opening scenes of the film provide long duration shots that allow us to enter House’s world slowly, through visuals and sound design. Let’s break the climax down (4:21–5:59) and see how Wruck crafts this moment. House’s monologue (in italics) is cut as I depict it here (Figures 1.9–19):8

Figure 1.9 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Shot 2 [4:29–4:32]

. . . mountains. Most were simply in the wrong place . . .

Figure 1.10 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Shot 3 [4:33–4:35]

. . . at the wrong moment.

Figure 1.11 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Figure 1.12 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Shots 5–7

[4:41–4:42]

Figure 1.13 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Figure 1.14 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Shots 9–12 [4:46–4:47]

Figure 1.15 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Figure 1.16 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Shot 14 [4:50–4:51]

Is it now?

Figure 1.17 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Figure 1.18 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

Shot 19 [4:54–4:59]

Will I know? [Eyes close. Sound of exhaling breath.]

Figure 1.19 Image courtesy of Stableford Studios.

In 38 seconds we get nineteen cuts with a variety of shots ranging from wide to extreme close-ups, the shots clearly telling the story with intentional and emotional impact. The lens in some shots is so close we can feel the intimacy of House’s struggle. But at the same time, note how Wruck shapes the sound design with as much care as the visual edit. This cannot be understated. The more you are aware of how to mix images (shot sizes, shot angles, shot duration) with sound (ambient, sound effects, and music), the stronger your film. Use Stableford’s film as a model for editing excellence.

One last note about cinematic storytelling, think about shots and the lenses you use in a psychological way, says Patrick Moreau from Stillmotion. His background in psychology gives us a way to think about how to use lenses and shot sizes, and it will also help with understanding how to shoot the story and how the editing can help tell the story when there is intention with the shot sizes and lens choices. We clearly see this intention of lens choices and shot sizes in Stableford’s promo, for example.

The Psychology of the Lens9

One of the strengths of Stillmotion is how their projects engage in such strong intimate images. This is why they moved from shooting weddings to shooting for the NFL (“The Season: Super Bowl XLV”) and why Callaway hired them to create intimate profiles of Callaway golfers. They not only understand story, they understand how to use lenses in a psychological way.

Figure 1.20 A fleeting, but intimate moment of an NFL player’s worried, furrowed brow captured in Stillmotion’s NFL video, “The Season: Super Bowl XLV.” The long lens and shallow focal depth isolate the player and shape the psychology of the drama Moreau helped craft through lens choices. (Image courtesy of Stillmotion.)

With a university degree in psychology, Moreau engages “psychology to tell stories” in his documentary work and now in his commercial work. He explains to me that psychology “helps us really understand the people we are working with as well as the stories we are trying to tell and how we can use our equipment to tell those stories better or in a more relevant way.” It’s not a set formula, but rather, it’s being present and making conscious decisions when it comes to camera and lens selection.

A wider lens and deep focus allows Moreau to capture his subject in a space that reveals the character’s emotions in an intimate way. Moreau explains how the psychological filmmaking process “forces us to question everything we are doing and it makes us really think about why this lens or why this camera tool” when shooting a scene.

Like all stories, it begins with character and not technology. “A big part of all of the filmmaking we do is really getting to know the people we are working with,” Moreau says. In many ways, this is the next step, the application of their MUSE story process, in production (described below). Then they can begin to “think about how we can interpret the story through our gear.” Lens selection is a big part of that gear choice. “A lot of people don’t really realize that when you change a lens you change a lot more than depth of field or field of view,” Moreau feels.

Within Moreau’s psychology of the lens, it’s a lot more than just framing the field of view. “People think you go to a wide lens because I want more in my frame or I go to a tight lens because I want less in my frame. Right?” But, he explains, you can easily change your field of view with a single lens by walking closer or farther away from a subject. “So if we can shoot somebody really close with say a 24mm lens or really far away with a 135mm lens what is the difference?” Moreau asks, but the bigger question is deciding “where we should be with which lens.” The answer is tied to not just how the shot should be framed, visually, but the psychological frame: “We always try to think of who our subjects are and how we can use our lenses to best communicate them.”

An example of using a wide lens occurs, Moreau says, when “you have somebody that is a little bit sillier or more comedic.” The Stillmotion team would move in close with the wide lens because it will “stretch and exaggerate people and really play off the energy, and you are going to feel their movement and the life in them a lot more.”

On the other hand, Moreau might use a long lens for a character “who is a little more dramatic.” Perhaps you want to accent this type of character by making him or her “a little more disconnected and looking outside in.” The long lens, Moreau adds, “is going to compress things, bring the features in, and that really shallow depth of field has you focus specifically on what we want you to focus on—but it also makes you feel that you are watching” the character from a distance, “rather than as an actual participant that a wider lens set closer will do.”

Figure 1.21 Moreau’s Stillmotion team captures an intimate moment in the wedding story, Winnie + Jerry.

(Image courtesy of Stillmotion.)

This kind of psychological and intimate lens work isn’t just about setting up a shot, however. Rather, Moreau’s background as a wedding cinematographer prepared him and his team to be ready to shoot “things as they happen.” By getting to know our couples, we are then able to predict things in a participatory manner. This cinéma vérité approach to filmmaking allows him to craft commercials that are “real” in the way of all cinéma vérité documentaries: “We don’t ask them to do something again.” Life happens in the moment, and to capture that moment is the artistry of Patrick Moreau’s psychological style of documentary filmmaking (and Stillmotion will weave this approach, along with interviews, into many of their projects). If a subject/performer is asked to stop and do an action over—especially when there are large crews—you may “lose that same honesty in what they are doing,” Moreau says.

For example, Moreau’s Stillmotion produced a series of intimate portraits of the Callaway golfers. In some cases, the series required his team to go into golfers’ homes. A large film crew and large cameras would have negatively impacted the intimacy Moreau was looking for. “We would shoot Trevor with his child in his backyard playing basketball or in his living room playing ping pong with his trainer,” Moreau says, “and being able to have small cameras, small gear we can get in there really quickly but still have that high production value.” (See Figure 1.22.)

Without such “small setups” with a “really small” crew, Moreau contends, it would have been difficult to get the shots he wanted. He feels subjects want to know that you’re going to tell their story properly and show them in the way they want to be shown. They’re “very vulnerable letting you into their house,” Moreau adds, but “by being very low impact and being a step ahead of them and letting them be themselves you get a very intimate reflection of who these people really are.” This is a key point in production house projects. Don’t take advantage of people and their spaces.

Figure 1.22 Patrick Moreau’s Stillmotion produced a series of intimate portraits of Callaway golfers. Here, Trevor’s child in the foreground plays with his father, soft focus in the background. The small size of the DSLR, along with a small crew, fostered his team’s ability to get such intimate shots. They use a Canon C100, now, with the top handle off to get the same intimacy (since the C100 is just a bit bigger than a 5D). (Image courtesy of Stillmotion.)

These intimate moments in the Callaway shots, Moreau believes, stem from the fact that “these moments are exactly like the way they would have happened whether we were there or not and to me this is the power of small cameras, such as DSLR and the C100. They allow you to capture real things.” And they expressed the production values of broadcast TV. He feels “the power is in the size,” providing the intimacy of realistic human portraits that “almost have an event edge to it, whether or not it is a natural event or it is just working with somebody who doesn’t have acting experience.”

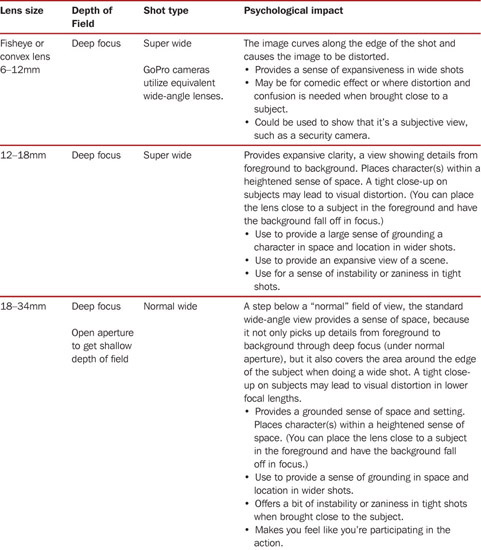

Psychological Impact of Camera Angles, Camera Movement, and Lenses

Below are several charts summarizing some of the psychological effects of camera angles, camera movement, and camera lenses. These don’t offer a formula or a hard and fast rule. In many ways, the impact of how the lens is used or how a camera moves or is angled is really dependent on the style of the story you’re telling. It is your responsibility as the filmmaker to set the rules of consistency in how a certain type of lens, camera movement, and camera angle is used in shaping different psychological situations. Also note that depending on the camera you’re using, you may have a different angle of coverage based on the sensor size. A 50mm lens on a C100 is different than one placed on a Digital Bolex, for example. All the focal lengths I’m providing will be based on the standard 35mm cinema scale—what we see in the Canon C100 and 70D DSLR, for example (the APS sensor is close to 35mm scale)—see Chapter 7 on cinematic gear for further discussion about this.

Types of Shots

The following terminology will help stage the descriptions in the charts that follow.

- Normal lens: The point of view of a single eye (not two).

- Objective shot: Omniscient viewpoint.

- Subjective shot: Subjective point of view. We’re conscious a camera is being used, whether it’s from a security camera or a news camera, for example.

- Emotional distance and intimacy in shot sizes:

- – Wide: Captures and sets the characters’ locations in a scene. Psychologically, it offers the least intimacy. It’s similar to having a conversation between two people standing against opposite walls in a room.

- – Medium: Normal conversational distance between people. Psychologically equivalent to people having a conversation at a comfortable distance without invading personal space.

- – Close-up: Distance of intimacy. We’re now in someone’s personal and emotional space. Psychologically we see this in emotional extremes of fights and sexual tension, as well as baring the emotional self, such as in a confession. This is why many people fall in love with movie stars—the close-up makes us feel we’re intimate with them, emotionally. As Patrick notes above, when composing a close-up with a long telephoto lens, it “makes you feel that you are watching” the character from a distance, “rather than as an actual participant that a wider lens set closer will do.”

- Depth of field shot: Use focus to frame a shot (foreground and background). Depth of field changes with aperture and with types of lenses—a wide angle will tend to provide deep focus, while a telephoto or long lens will provide a shallow depth of field, where you can choose whether the background, middle ground, or foreground is in focus, allowing the filmmaker a different type of framing. A rack focus occurs when changing focus within the same shot (going from foreground in focus to background in focus with the foreground falling out of focus, for example).

Camera Angle

The height of the camera and camera angle in relationship to the subject also determines the psychological nature of a scene:

- High angle shot: The camera’s point of view is from on high looking down onto the subject, causing the subject to look up at the camera, resulting in a sense of subservience and weakness. There is no intimacy in this type of shot, due to the balance of power being off.

- Low angle shot: The camera’s point of view is looking up at the subject, so the subject must look down at the camera, giving them dominance, authority, superiority, and strength. There is no intimacy in this type of shot, due to the balance of power being off.

- Level shot: Camera’s lens is at eye level to the subject. It provides a sense of evenness of power since no one is looking down or up at someone. Use a level shot with a normal lens and it will provide intimacy in a close-up, due to an equal power relationship.

- Dutch angle shot: Camera tilted unevenly from the horizon line. Tends to induce a sense of disarrangement or confusion on the part of the subject.

- Front shot: When on axis and level, provides the strongest intimacy since the full face is exposed.

- Side or profile shot: Seeing action from the side, it pulls us away from intimacy since we’re not seeing the full face where emotion is most fully expressed.

- Rear shot: The strongest emotional distance from a character, since we do not see their face. Because of this, we also feel tension because we don’t know what the character is feeling, doing, or looking at.

Camera Movement

In addition, camera movement is another level of influencing the emotions of a scene and what it reveals. Some filmmakers add motion for the sake of visual stimulation—and in some cases that technique works. But when used consciously, camera movement can be used to reveal information and emotion, and even a passage of time, cinematically. Vincent Laforet, in an interview, discusses how many amateurs move the camera for the sake of moving the camera, resulting in unmotivated camera movement:

The reality is that they’re breaking one of the cardinal rules, which is every camera move should be motivated to do something either by the action in front of it or the director’s will to reveal or conceal something, to walk you through a space, or to make you feel a certain emotion.10

Some terms dealing with camera movement:

- Shaky cam shot: The handheld look. Use a wide lens to minimize extreme motion. The longer the lens, the more obvious and extreme the shake. The camera calls attention to itself, providing a newsreel or raw documentary feeling as if the action is occurring unstaged in the moment.

- Absolute motion: When the camera moves, but stays in one place on its axis (such as on a tripod), the foreground and background move at the same rate of speed onscreen. Found in pan, tilt, and zoom shots. Not naturally occurring with our eyes.

- Relative motion: When the camera moves through space, the foreground moves more quickly relative to the background. Naturally occurring when we pan or tilt our head. Found in push-in, pull-out, jib, and tracking shots.

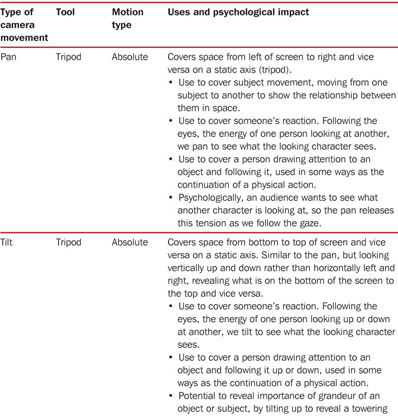

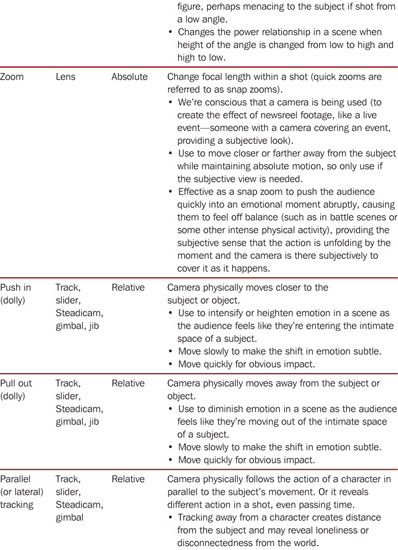

Table 1.1 Psychological Impact of Camera Movement

Additional resources on camera movement:

- Steven D. Katz’s Film Directing: Cinematic Motion (Michael Wiese Productions, 2004).

- Vincent Laforet’s Directing Motion (see http://directingmotion.mzed.com/).

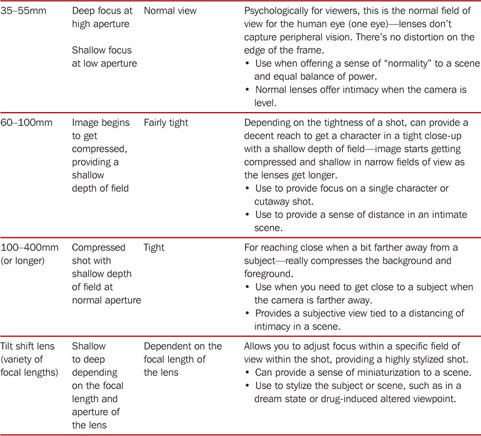

Lenses

Note: The more extreme the lens, the more it calls attention to itself, causing a subjective viewpoint, while normal lenses tend to be objective in their viewpoint.

Table 1.2 Psychological Impact of Lens Size

Muse—A Storytelling Tool from Stillmotion

At the risk of sounding like I’m plugging Stillmotion’s course, they do offer MUSE, a process and toolkit for learning how to tell “moving” stories with intention. They offer a course on their storytelling method—more info at: http://Learnstory.org.11 In their course, they give production house storytellers and filmmakers the tools to develop character-centered stories. They include methods for developing the story—not techniques of production. This is a well-intended goal and a missing piece for many who lack such skills. Many people understand the filmmaking process, especially those who have gone to film school, but it seems that few know how to find and create a strong story. If anything, if you apply the cinematic techniques discussed in this chapter to a strong story, you’ll likely make a strong film.

Stillmotion’s vision for MUSE is:

We see a world where storytellers of all varieties—filmmakers, bloggers, marketers, agencies, non-profits—are more intentional in the stories they craft, and that their stories truly do change the world. We see a world where filmmakers are no longer tripods—they have the confidence in what they are trying to say with a story, and the incredible clarity to bring it to life in a way that moves their audience, thrills their clients, and fully realizes the vision they have in their mind’s eye. Where non-profits are using MUSE to connect people to their cause, raise more money, and create more impact. Where marketers and agencies use MUSE to be more conscious storytellers that use story to create results around things that matter. (MUSE Storytelling Tools, p. 5).

If you need to up your game on storytelling—and most of us do—MUSE is an online class with several learning modules, and directly reflects the ten years of learning and experience Stillmotion has applied to its Emmy-Award-winning work. The first half of the course (steps 1–4) is the process by which you listen to a client and the potential characters of a story with intention. It includes:

- People are the characters in our story who give our audience someone to relate to. People connect with people, therefore we can use the notion of empathy to help move our audience.

-

Place is where your story happens. It grounds the story in reality. Place is more than just a backdrop—it’s a way to let your story speak for itself, display your character’s authenticity, and foster trust with the audience.

It includes the environments, objects, situations, and time for your characters in the story.

- Purpose is what your story says to the audience. It’s what you want your viewer to take away from the story. By having a well-defined purpose, you take on one clear vision that resonates throughout your team. (This includes the development of keywords to guide the production.)

- Plot is the structure of your story. It allows you to maximize the impact of your story by creating an emotional arc and organizing elements into the beginning, middle, and ending. This includes the development of conflict, questions that lead to answers, and a resolution.

The Stillmotion team feels that these “4 Pillars” help create a sense of “connection, authenticity, meaning, and engagement.”

In short, the MUSE course provides a methodology to help find characters that speak to the heart, create stories that engage in meaning, and help shape a plot that stems from their uniqueness and passions, all of which revolve around an unanswered question that helps drive the story. Ultimately, it puts Stillmotion’s ten years of award-winning production house work into a course that others can apply to their own work. See Chapter 8 on how Stillmotion applied some of the MUSE steps to the book promotional film, My Utopia.

Storytelling and Filmmaking Tools

Stillmotion’s MUSE isn’t the only way to develop stories and characters, of course. These resources will help you up your game in storytelling—some of which influenced Stillmotion’s approach:

- Aristotle’s Poetics. Read it here: http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.mb.txt

- Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots. See a summary here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Seven_Basic_Plots

- Stillmotion’s MUSE: http://Learnstory.org

- Alex Buono’s The Art of Visual Storytelling bundle (Visual Style Workshop, Visual Subtext Seminar, Cinematography Workshop): http://vs2.mzed.com/download

- Vincent Laforet’s Directing Motion: http://directingmotion.mzed.com/streaming

- Shane’s Inner Circle: https://www.hurlbutvisuals.com/blog/shanesinnercircle

Worksheet: Shooting in the Cinematic Style

- Identify the 4 Ps from Stillmotion’s MUSE process:

- People

- Place

- Purpose

- Plot

- If you take the MUSE course, go through the steps for each client-based story you work on.

- Write a descriptive shot list.

- Choose the type of lens for each shot and/or scene in order to express the right psychological impact in a story (and this may involve changing the camera angle).

- How do the shots show the story unfolding, visually? If shots are simply illustrating or decorating the dialogue or narration—and any shot would do the job— then revise it so that every shot counts, propelling the story forward visually.

-

Describe the soundscape for each scene—be sure that every piece of audio is consciously designed to enhance the mood of the story.

- Natural sound elements.

- Music (each scene does not need music; use music for emotional transition points); justify why you need music in a particular scene or at a particular moment.

- Voice

- Who speaks and why do they speak?

- Does the voice tell the audience how to think and feel or does it share an emotional experience?

- If there’s too much talking without space in between dialogue or narration, then the ambient soundscape will get lost.

-

Identify the moments of tension and release in the film.

- Describe how audio is used to help shape the rhythm and pacing.

- Describe how voices help shape the rhythm and pacing.

- Describe how music helps shape the rhythm and pacing.