Now that there’s an understanding of what you need to do to stay in business, we now shift, in many ways, to the heart of this book—the reason you have your business in the first place. This chapter starts out with Amina Moreau discussing how to interact with and treat clients, followed by what Stillmotion uses in their bid and treatment process. I also explore how Stillmotion use keywords as a way to communicate with a client. It also includes some ideas on brand strategies that you can apply to your clients (making you, in many ways, a person who will help brand a client’s product or service through your video). It then moves into a workshop on the use of keywords (developed by Stillmotion) and utilized by Zandrak in helping them develop a story for the Moodsnap app. Shifting to a visual pitch model, the book examines the one Zandrak created for Moodsnap, which led to a successful contract, including a discussion with Charles Frank on his process in creating the visual document— and how the project ultimately changed from the initial pitch. This is followed by a script that Zandrak’s Kyle Harper wrote for a promo video developed for Northern Arizona University’s Honors Program. Lastly, I describe the process of creating a production budget quote.

Making a Connection and Ways to Find a Client

The foundation for your business revolves around the ability to make connections with people. This is why you need to put yourself out there and network. (In some cases—especially when you get established—you may end up getting clients through advertising agencies.) In either case, networking is the process by which you put yourself out in the world and let people know who you are and what you do. It’s where you engage with others at a real level. You can’t tell a client’s story if you don’t talk to a client. And if you’re superficial or don’t care, then you’ll end up finding no clients or getting clients who are also superficial and don’t care.

Alex Buono, Director of Photography for the Saturday Night Live Film Unit, in an interview in Film + Music, gives this advice about networking:

The way you can control your career is by getting to know people, actively going to film festivals, watching films, engaging with the filmmaking community, sharing your work, helping people. When I was first starting out I worked for free all the time just to meet people. It’s absolutely better to be working on something for free than to be sitting around doing nothing waiting to get paid.1

There’s three aspects to networking, according to Amina Moreau of Stillmotion:

- ”It’s being involved and making the effort to know what other people in the industry are doing. Whether they’re fellow filmmakers or they’re manufacturers, we have a lot of close relationships with manufacturers of gear because we use them first of all. But then second of all we can provide feedback, and third, if we can support them through helping them market their stuff because we honestly believe in it, then why not?”

- ”Develop friendships in the industry.” You’re not just treating a shoot or people like a tripod. Connect to people as people.

- ”Kindness goes a really long way,” Amina adds. “I think when you develop relationships with people that are more than just as a business but you actually care about them and you make the effort to follow up a week later, and ask, ‘How are you feeling? How are you doing?’ It’s amazing. I’m not saying I do it as a business tactic, because I do care. When you put the effort into caring about people the way that you do about your own family—they notice. And that means in the future they want to work with you more, or they want to help you more if you’re in a bind, or if you need a favor, such as needing exposure or something like that. This is what Stillmotion is founded on—this idea of let’s do something that makes the world better. I almost don’t care in what way, let’s just make it better somehow. Let’s leave our mark and not do something for ego’s sake. People need to start caring about things that will improve it and not just selfishly do something just to get ahead. A lot of people feel like if they can’t do everything, then why do anything? Nobody can do everything, but if everybody did a little bit of something, it can make a difference.”

Ultimately, if you’re trying to run a business and get clients for that business, you need to be excited about your work and about your client. “Excitement is contagious,” Amina exclaims. “Engage in something you truly believe in, something you live and breathe,” she adds.

Where can you find potential clients? You could place a standard ad in Yellow Pages or its online equivalent and people may call you. In some ways you need to go to conventions and networking parties for the types of business you might want to do.

Andrew Hutcheson at Zandrak recommends that you look at startup companies. “There are dozens of these in every city, and sometimes they’re on college campuses, sometimes they’re in financial districts, universities might have some business incubators. These will have potential clients that are just getting started, and if you’re just getting started any business knows that it needs an online presence and it needs a video presence. It’s still the most effective form of marketing. That’s an opportunity for you to meet someone and make a connection. They probably won’t have all that much money, but it’s a place where you can get started. You can help out a nonprofit, or a local business that wants to expand to a certain extent. You need to market your services.”

But the key point isn’t to just tell people they should hire you to do their video. “They’re probably not going to buy it,” Andrew states. It turns them off. “But if you discover what their problems are, and how this video will solve the problem, people will pay for a solution,” he explains. Take time to figure out how to sell yourself and your services to people and how to do it “in a way that it’s in their best interest to do a video with you,” he explains. “A cornerstone of media is just making people feel convinced that they’re actually getting the better end of the deal paying for this service.”

To make it happen, you must find out why they want a commercial or a promo. “Ask that question,” Andrew says. “Why do you want to make this commercial?” They will give you a reason, he continues, “then it’s your job as an artist and a storyteller to interpret that need and discover the emotion behind it.” This is one of the key points that might set you apart from others. “You are not selling someone on a shoe that’s lighter and that’s made from a more durable rubber,” Andrew contends. The factual stuff. “You are selling them on a shoe that makes them feel that at any minute they could be doing parkour. You are not selling somebody on the car that has the V8 turbo engine. You are selling them a car that makes them feel badass. Find the emotion and then you sell them on the emotion in the commercial.” That is how Zandrak approaches their branding projects. “We work with a brand and it’s our goal to find out what their agenda is, what they want to accomplish, and then we translate that into a commercial that is emotionally appealing.”

Develop a Relationship First, Then Develop a Story

Before Stillmotion gets to the money aspect—the estimated budget—they “put people first.” As Patrick Moreau explains, “We’re not talking about prices and production and a lot of that stuff at first. We’re getting to know the people. What makes them different? Whether it’s a product or it’s a service, we want to know, why does it need to exist? Who created it?” He would rather, as he says, “get at some of those deeper questions, as opposed to just getting a call from a coffee shop who wants a commercial and asking them such business questions, as ‘How long do you want it to be? Where’s it going to air? What’s your time frame? What’s your budget?’” That’s taking the tripod approach. Rather, Patrick says, they take this process in steps, because “nobody wants to be a tripod, nobody wants to be told where to stand and how to shoot and what to do. We are storytellers and we want some sort of creative vision. And we can gain that by agreeing not on what we are going to do but what we were trying to say,” he explains.

So instead of those types of generic questions, they’re more interested in asking:

- Why did you open a coffee shop?

- Why do you love coffee?

- What is this about for you?

In this way, they’re making a connection with a client, developing a relationship. “We get to know them and explain to them what makes our process different and what we believe a story can do and how we would approach it,” he adds. “Those are really our first conversations. It’s about putting people first, moving people emotionally, how we’d approach it, and that so much of this work is in preproduction.” In addition, if they’re local, Patrick says, they prefer to meet clients in person. “Amina will often Skype with them if they’re not local, and try to make it as personal as possible.”

The questions that ask “Why?” and “What’s in it for them?” comprise the first steps in getting to know clients—and it’s the process that determines whether or not the Stillmotion team clicks with the potential client. If that process goes well, they start talking about their coffee shop video, for example, and provide rough estimates based on what they think the preproduction and production process will be. “We provide rough estimates with wide ranges because we try not to pigeon hole ourselves without nailing down the story first. So we might give somebody a range that’s going to be $25–40,000 and explain that we need to dive in and really get to know what the story is before we can be specific with the budget.”

“We definitely don’t want to just develop a concept or idea until we know what the story is," Patrick adds. “So the first thing we do is develop keywords— which helps us determine what we’re trying to say with the project.” (The keyword development is explored later in this chapter, and in Chapter 8 in the case study on Stillmotion). They’ll work with and present these ideas to the client. “After we agree on what we’re trying to say,” he adds, “then we’ll come back with the creative.” Getting into this development phase may take a while, and with a large client Stillmotion will ask for a $2,500–5,000 retainer just to do the research, just to come back with these keywords or what they’re trying to say in a concept, Patrick explains.

At this stage, Patrick says, “If they love the concept and the direction of it and if it’s within their budget then we’ll go with that concept.” Of course, they have the initial conversation about what their budget is so they can see if the concept (along with the preproduction and production planning) is reasonable for the client’s budget. However, Patrick tells me, “If in doing our research we feel like the story needs something completely different, then we’ll just be completely up front with them.” If they have a certain budget, and Stillmotion feels they can do it for less, they’ll let them know. In some cases it may be more. It depends on the parameters of the project.

Because of the step-by-step story process they have developed—how they make it “tangible and clear on the process and expectations,” Patrick says, “clients tend to feel great when we come back and say here’s the keywords based on what we discussed, about what you want to say in the video, and this is how we’ll approach it. For example, we might tell the client,” he explains, “If one of your keywords was global and you guys have offices everywhere we can’t just shoot here, we need a large travel budget. We’ll provide different options and that kind of thing. That’s how we work through it.”

Patrick brings the point home about the importance of approaching the project creatively based on story—and why they emphasize the importance of their MUSE story development process (outlined in Chapter 1). It’s a tool for working with clients, to get clients on board with a creative vision shaped by the Stillmotion team’s passions. Because there’s a shared vision there’s little to no conflict with a client when you go into production. By going through these steps, Patrick says, “there really is a lot less room for disagreement on how you’re going to approach the film creatively”:

- Developing keywords.

- Setting expectations.

- Clarifying what is trying to be said with the project.

If you listen to the story it really has one shape, one form, and so then the debate becomes, ‘Do I really want to tell this story in an authentic way because we are going to listen to keywords and come back to you with the best way to express this for you?’”

What may happen, however, is getting a CEO of a company telling you that they want the story done in a different way, even after you’ve developed your creative vision for it. “They want to put a spin on it,” Patrick says, and when this happens we know that “we’re getting sold something, we’re getting told something”—these “are not the stories we want to tell.” These are the standard commercial projects that fail to engage storytelling in the cinematic style. “Our job,” he explains, is to try to “go back to the idea that people are going to connect with something that has substance for them, that has purpose, that offers them value and if you’re trying to shift or spin or add another slant to it that is not authentic, people are going to sense that and you’re wasting our time and your money.”

If a client doesn’t want to utilize Stillmotion’s storytelling approach, then they won’t do the story. That’s rare, however, Patrick explains, because they’re so clear in the storytelling process—using keywords—and developing what they’re trying to say in the project. Even when they run into issues with clients during the planning stages, they can use those keywords as a “filter” through which they can run every decision.

For example, a client might say, “‘Hey, why don’t we interview this person or why don’t we do this?’” Patrick says. “We would reply, ‘Okay, well, how does this express your keywords? Does it or does it not?’” Sometimes they’ll have ideas the Stillmotion team hasn’t thought of, but sometimes they may just revert to an old concept, such as interviewing the CEO. Patrick explains that they would push back and say, “‘One of your keywords is flat, meaning you don’t have a hierarchy so we probably shouldn’t have the head person . . . we should probably have people that are all on the same level, and then they might realize, ‘You’re right, we don’t have to do that’ . . . And that’s exactly how those conversations go when we use our tool to drive [the] creative and get agreement and communicate why it is we’re making those decisions.”

Before looking at a case study, let’s discuss what it means to help a client deliver their product, message, or service. As Andrew Hutcheson noted at the beginning of this chapter, you are discovering a client’s problem and offering them a powerful solution through your film. Let’s dig deeper into this.

Help your Client be the Brand they Need to Be

Be the thought leader in how you approach client-based work. Lead your client down a path that will allow them to be leaders and visionaries. In this way, your work will help their work and this is where your creativity, your mission, your vision can help coincide with your client’s need for a solution—and this is the real reason why client interaction is the most important thing you will do with your company. It’s not about how cool your gear or video is. It’s about how cool you’ll make your client. In this way, you are helping your client brand their product or service through your video.

Glenn Llopis, President of the Glenn Llopis Group, discusses six brand strategies in his Forbes article, “6 Brand Strategies Most CMOs Fail To Execute”.2 He feels that if you copy what others are doing, you’re failing to be creative and will fall behind by just doing what has already been done. If they need to “reinvent” themselves, Llopis says in the first step of his brand strategy, be there to guide them. If you or they are always reacting, then you and they are not on the cutting edge. Below, you’ll see how Stillmotion and Zandrak are thought leaders in the video production house business through their approach and style of work. You need to help set a vision for your client that puts them on the cutting edge through the messaging that occurs in the film you’re creating.

In addition, is your video—and your approach to communicating your vision for the client—relatable? A potential client shouldn’t be trying to figure what you want to do. You should express laser focus. So, Llopis feels that that identity should be “deliberate” and “forward thinking,” a key point of Llopis’ second brand strategy. So when you’re creating a piece for a client, whether it’s a work that highlights a product or a service from a nonprofit—whatever your video is meant to do—be sure it helps your client with their identity. Remember, you’re trying to do two things with your business:

- Let potential clients know who you are and what you do (your vision)— and this should be communicated through your website (from Chapter 4).

- Help solve a client’s problem—your video should be the solution for their needs in getting their product, message, or service out. They’re looking for clients or customers through your video.

In this way, we move to Llopis’s third point, that you’re helping to inspire and communicate hope—and this will make that message last. What does this mean to the production house leader? Create projects and attract clients that inspire people through the work you create for the client. In the case study with Zandrak below (and in Chapter 9), we can see how the video they did for Moodsnap helped reveal the lifestyle of a young couple on a road trip that reflects the hope and lifestyle of Moodsnap’s app. If your client sees you engage in such work, they will likely want you to help discover message strategies that inspire and give hope to their clients through the stories they want you to create for them.

In his fourth strategy, Llopis argues that you should be willing to continually innovate and be proper with your timing. Again, if you remain innovative you will support your clients in being innovative as well. In many ways, this is why you cannot be a tripod, as Patrick Moreau emphasizes about Stillmotion. You have to be a brand strategist for yourself to attract clients, and then be a strategist for your client through the video you create. If you’re doing your job right, showing your excellence, then your potential clients will begin to know you for your excellence and they’ll take note. As a visionary for audio-image storytelling, you should be helping your client tell a story that puts them on the cutting edge, and if you’re trying to help them with the release of a product, service, or message, you should deliver on that promise.

There’s an element of “corporate social responsibility” that you and your clients should think about, says Llopis in his fifth strategic point. If your projects are able to help improve the world then more opportunities will open up. This kind of approach, where you are thankful and socially responsible, will likely attract other clients who appreciate such stewardship.

Llopis’s sixth and final point discusses the idea of brand legacy—how does it impact the business or lifestyle? In other words, does your vision and mission for your company really do what you want it to do? Is it designed simply to start or run a business so you can do any type of job, or does it help sustain the businesses and nonprofits, the lifestyle your clients are trying to shape through their product, service, or message?

If you can apply these concepts in a visionary way to the film you’re trying to create for a client, you’ll be in a position of leadership in helping them set that vision. You’re the professional storyteller. Help guide your client through your creative and visionary process. After making a connection, developing a shared vision with the client, the next step usually begins with a treatment as a way to communicate your initial vision.

What’s in a Treatment?

There is no one way to create a treatment, proposal, or production quote bid. Each production house company approaches it differently and each project may require a different type of template—there is no one formula. Zandrak utilizes different types of styles and content in their work. A project I did for the American Community School in Amman, Jordan required just a brief outline and a budget. Stilllmotion uses the following elements in a bid and treatment in their projects:

- Concept: A brief overview of the concept for the project, to be expanded upon later if necessary as a treatment.

- Pre-production: Casting, pre-interviewing, scouting, and learning the story.

- Production: Days required for production, and a list of resources—the Director, the DP, a second camera, major pieces of gear should be listed.

- Post-production: A list of the deliverables—“one 3–5 minute film in HD, web ready,” how many rounds of editing are required, color correction, sound mixing. . . . all these things you should mention briefly.

- Soundtrack: Here you might want to give some options, with the estimated costs for licensing music. A song with a one-year lifespan is going to be cheaper than a song with a perpetual lifespan, and that’s a choice they’ll have to make. We list the cost for both the one-year and the perpetual lifespan, usually indicating the cost for anywhere from 1–10 songs.

- Travel: “We’ll make all the travel plans . . . you give us this much money.”

- Rights: A brief statement of the ownership/rights to the material, and that we reserve the right to show the material (when applicable—this isn’t always the case).

- Project Estimate: No fluff—just the estimated cost of the entire project.

- A Final Note: We don’t want the last thing on our bid to be a big dollar sign and nothing more. Here we’ll make a note about why we’re excited to work with them, and why we believe in the project.

Keywords and Story Development

As part of Stillmotion’s vision they have created story development tools as a part of their education outreach, showing what they have learned from over ten years of experience, and teaching at workshops around the world. (See Chapter 1 for a summary of the entire MUSE process.) It involves the four Ps and keywords:

“We Believe that Story is Based on 4 Ps: People, Places, Purpose, and Plot”

The ‘P’ you put first, or prioritize, determines the type of story you’ll end up telling.

Lead with Plot and you have an action movie. Lead with Purpose and you have a commercial. But when you lead with People, we have the potential for an emotional, character-driven story.

We believe that you need to let the story move you, before you try and move the story. And so we start with listening. To the people, places, purpose, and plot that exist within any story.

This is why we feel that the best storytellers are the best listeners—they see and hear what others don’t and allow the story to come to them.

http://www.stillmotion.ca/museprocess

See http://kurtlancaster.com/contracts-and-forms/ for a sample creative brief from Stillmotion. It includes a space for keywords, characters, treatment, and storyboard based on the MUSE process.

To summarise:

- People represent the who of a story.

- Places are the where and why.

- The purpose is the why of a story. It revolves around the five keywords by which they become “a lens to filter every decision.”

- The plot is the beginning, middle, and end—the how of a story.

What follows over the next few pages is a transcript of a fast-moving discussion by members of Zandrak as they utilized Stillmotion’s keyword technique in developing the foundational ideas for their Moodsnap short. Note that the Zandrak team members have already talked to Moodsnap in order to get a sense of how the app works (and they’ve recreated this discussion for the author). The discussion occurred among the four members of the team: Andrew Hutcheson, Kyle Harper, Charles Frank, and David Brickel. Since it moves fast, I do not designate who is talking, but rather highlight the fact that the four of them are operating as a team. They push and challenge each other as they develop a consensus. It’s like being in a writer’s room or the locker room before a game—ideas flow fast and may appear jumpy at times, but the overall control revolves around what they feel are the best words to describe what the Moodsnap app will be like and how they can translate that into a short film. I provide the transcript in order to show that ideas don’t just pop into place by magic. The dynamic conversation reveals the creative process in embryo, gestating to completion over time. It also shows the potential power of Stillmotion’s process. It’s a process I have my students engage with in my production classes at Northern Arizona University. Even when they do nail down these keywords, it’s just the beginning step to writing a storyline or treatment (which I examine in the next section). Remember the keywords are drawn from their research and pre-interviews with their subject—they’re not flying blind, but drawing from previous conversations they’ve had with the client.

Andrew writes and erases words on a whiteboard in their small office in Boston and they jump right into the process, trying to discover the best words to define the appeal of the Moodsnap app.

Moodsnap is accessible, definitely.

Personalized.

Great.

Well, it’s about discovering new music, isn’t it?

Yeah, it’s good for discovery.

Discovery, adventure. Exploration is probably better than adventure.

Exploration, what about—

Context.

It’s also introductory, introduces you to new music.

It captures emotionally driven material.

I think it’s capturing a moment, it’s convenient.

Enhances what you do, enhances the moment.

Nostalgic. Memorable. Relevant. Innovative

It’s communal. What else we got?

Something about the music relating to the context. Like pairings.

Relatable.

Fitting.

Fitting is better, yeah.

Anything else?

Motivated.

Nostalgic.

Something about having the right music for the right place for the right experience.

Fitting, pairing, contextual.

Yeah.

Figure 6.1 Andrew of Zandrak writes down some keywords on a whiteboard in their office. (Photo courtesy of Kurt Lancaster.)

Anything else, or do you want to cut it down?

Let’s start to cut down.

We’ll see what we’re missing when we start to get rid of some sort of . . .

So, this point you know we’ll cut down the words that don’t fit.

Motivated.

Agreed.

Relevant.

Yeah.

Accessible.

Mobile.

Introductory.

Maybe not mobile.

Capture.

Relatable.

Yeah.

I think music goes.

Yeah, I don’t think we need it.

How about visuals?

I think adventure.

Discovery.

I also liked multi-sensory and emotional.

Yeah those are good. I don’t like personalized.

I like user-curated. It gives an important element of it as well.

That’s fair.

And contextual I love.

So we like contextual, we don’t like fitting. Don’t like experiential. I think it’s summarized like it’s an app. It is experiential by nature.

There’s some apps that aren’t experiential.

When I think of experiential, I’m thinking of what it does outside the app. The app is a catalyst.

That’s a good point, I didn’t think of that. Let’s lose elegant and inspiring, though.

Yeah.

Convenient.

Yeah.

Pairings.

What about emotionally-driven, is that like, could that be a hyphen?

I think just emotional.

Let’s start getting rid of some of these words. I think we lose feelings and I think we lose music, because it’s not just about music.

Nostalgic and mobile.

Figure 6.2 Kyle, David, and Charles discuss with Andrew keywords for the Moodsnap app. (Photo courtesy of Kurt Lancaster.)

What do you like about mobile?

Yeah.

I think that the problem is it doesn’t distinguish itself.

Yeah you’re right.

So now we have these guys to look at: emotional, experiential, user-curated, contextual, and multi-sensory.

Wait, how is it multi-sensory?

Because it’s visual and music, so multi-sensory stays, definitely, so does discovery.

Does discovery stay? Is it about discovering new music? Or is it about finding the perfect playlist?

Alright, yeah.

Is contextual important?

Yes.

I feel like we have only one word about the visual aesthetic for the app. Being elegant, which has been cut. I wonder if there’s maybe something that can tie into it.

I think experiential would tie in the fact that it’s like the experience of using it, as a part of it.

I would keep experiential and lose emotional, personally, I think emotional—

Is covered under what?

It’s covered in Moodsnap.

I think it’s pretty essential to the brand.

Or we write them both and just admit it’s a middle ground.

What’s the difference between experiential and emotional? Inspiring?

I think about emotional and driven is kind of like that.

But I don’t think that’s experiential. I think emotionally driven talks about it. I think that’s just emotional, expanding off it.

I see. My only thing would be that if it’s emotionally driven, then it’s causing an experience.

How user-curated is it?

That’s a big part.

They submit the songs.

Yeah, there’s an image then all the users submit songs onto that and then through the algorithms it finds it.

I would be more inclined to lose contextual and keep emotional and experiential.

I think that contextual—

Emotional is the context though. If you remove the term emotional it describes both the idea of pursuing feeling, but also describes the context in which you’re choosing things.

He talked about it so much in his brief about how this app is really about context.

Okay, in which case we can hold onto that.

I think it’s an important element. I would almost say that emotional is covered in contextual.

We can do that, then we keep experiential, those are the five. Okay.

Before we solidify them, we can see if there’s any gaps that we feel are missing.

Yeah, I don’t see any. What about you guys?

Let’s see them all up first.

They’re all up: Experiential, user-generated, discovery, multi-sensory, and contextual.

Alright, we’ve covered the soul of the app. That’s core. We’ve covered some of its functionality.

What it does for you?

We’ve addressed users a bit by talking about being user-curated, and how they’ll interact with it.

I think that’s good.

Okay. So we have to come up with one 90-second spot based on these five words, and it’s going to be for online use.

What’s clear in this ping-pong style discussion is how Zandrak members make the work stronger when they let go of egos and push for what’s best for the client, the story, the app—and this would get filtered through the five keywords they collaboratively generated: Experiential, user-generated, discovery, multi-sensory, and contextual. After the keywords are completed, they start brainstorming. Andrew Hutcheson says, “Everyone goes home that night and they think about some ideas, come in the next morning, we all have two or three ideas each, bring them up, put them on the board, look at all of them. So we can see what they are, and take the best parts of each and turn them into the final idea.” It’s a collaborative approach. “Usually what ends up happening is everybody comes in with their ideas to talk about and in the process of talking about the ideas we come up with either a middle ground or an entirely new idea that everybody just loves,” Kyle Harper adds. Charles says that, “We all have pretty full narratives in mind, and we’re all willing to let go of them so long as they are for the betterment of the full piece.”

After brainstorming and coming up with the ideas, Kyle explains how “we get these ideas together, we flesh one of them out and write a synopsis for it. And we’re trying to put that together and send that to the client. And after that point it’s going to be about developing that treatment.” Charles says, “Once we create the synopsis, the outline of what the piece is, we’ll contact the client with just a general overview of what it is, whether it be a Skype call, a phone call, or just an email with the synopsis. If they like the direction in general, we’ll create a fuller treatment that talks about the execution, contains some visual samples, and then in the case of Moodsnap we also talk about the rollout plan, what other kinds of pieces we would link to a campaign in this style, as well as an estimated budget.”

Andrew adds that the budget is important. “Because if we get the idea and the client likes it and it’s all going great, then the client says we have ten thousand dollars, and we say we can’t do this for that, no way. We’d end up walking away with maybe a hundred dollars, if anything.” So they need to shape the budget realistically. Sometimes it might cost more than a client has budgeted. “That’s why we make clear the defining parameters of the project,” Andrew says. “Here’s the idea, here’s the budget, and they come back and say we have a third of the budget, and then we can say, ‘Okay, well you still love the idea, how can we scale the idea, adapt it to fit your budgetary constraints.’” This process can be just as creative. “It is fun,” Andrew adds, “that’s the creative brainstorming, using creative budgeting constraints.”

The Visual Pitch

Written pitches or proposals are normal in the industry. But Zandrak isn’t normal. Since videos, or short films, are visual, why not make the pitching and proposal process visual? It still contain paragraphs, but it doesn’t focus on a lot of text. Once Zandrak discusses keywords and develops story ideas from that, Charles develops a treatment for a client that “portrays the visual aesthetic of the piece. I just like them to match the aesthetic of what we are doing so that they get a sense of who we are and we are not just presenting them a Word document with a bunch of copy, because I don’t think that is representative of our style.” (See Figure 6.3.) Charles hopes that this approach shows clients that a visual document proves “that we go above what their expectation is so they know we are invested in what they are doing.”

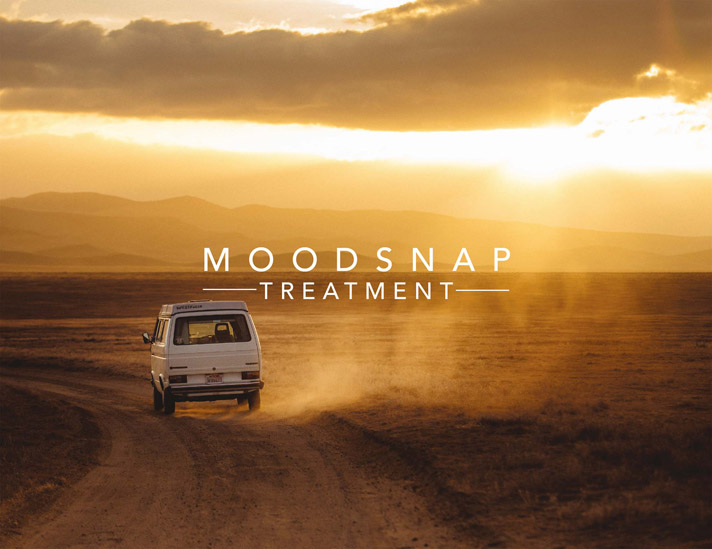

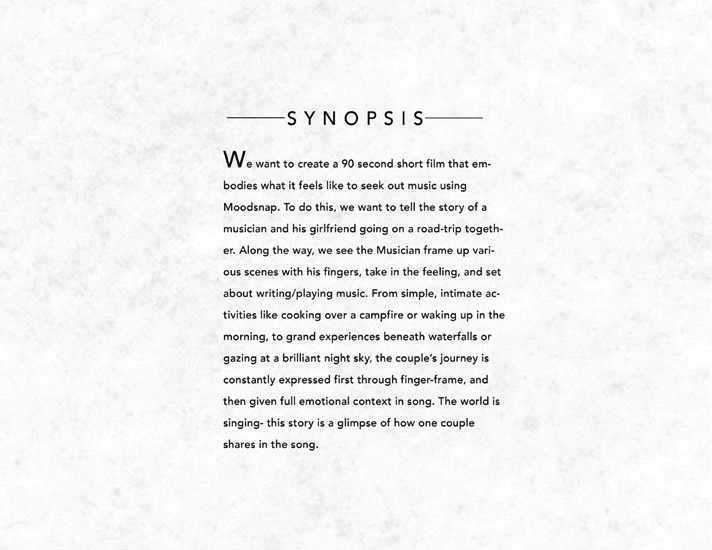

Charles says that, “The thing that takes the longest and it might look super in-depth, is finding images that are really fitting for the piece. We want to do a road trip so the opening page show this road trip. This is how he received it.” This is not a still from the film. It’s concept art, providing the client with a possibility or potential look for their film. It allows the client to sense the mood of the piece, which Zandrak says is much more difficult to convey with words. When they do words, such as in their synopsis, it’s sparse, it’s poetic (see Figure 6.4).

The synopsis, Charles explains, is “just a minimal approach with the texture on the page and the elegant font.” When comparing the finished product with the original, Charles admits that “the original concept is a lot more involved. It was a lot more complex. I had the boyfriend and girlfriend framing up these moments together and then based on the frame they create, they make a song together that represents that frame. And that was very much in line with exactly how Moodsnap works. But as we were getting closer and closer to shooting, I just had trouble imagining in my head that process being natural and organic.”

As Zandrak did their research, such as scouting locations, casting and meeting the actors, Charles started to see the edit of the film in his head. “I start thinking about pacing, I start seeing visuals, I start seeing the wides, mediums, and close

Figure 6.3 Moodsnap—the cover page to their treatment. (Courtesy of Zandrak.)

Figure 6.4 Zandrak’s visual treatment for Moodsnap, page 2, the synopsis. (Courtesy of Zandrak.)

shots and how they’re cutting together,” he explains. “I start seeing the inter actions of the couple because it’s all starting to materialize and be real.” For Charles, the pressure of a looming shooting date helps fire his imagination. “And when it got closer and closer I imagined the performers having natural interactions and then one of them pulling up one of their hands and taking a fake snapshot. And every time I imagined it happening I thought, ‘That’s going to look fake. It’s not going to look real. It’s going to look like this is for the app.’” He felt trouble looming with the original vision that Zandrak and the client had worked out. But rather than meticulously follow the plan, he decided to listen to his intuition and confront his fears. “So finally the night before shooting I called the client and said, ‘Listen I know this is so last minute and it’s crazy, but I just don’t see the original idea for the piece working.’ I told him that I know I should have thought of this sooner but now that it is here in my head, I can’t make it work.”

Charles’ intuition and passion paid off. The client, Charles says, replied, “‘It’s okay, I trust what you see and I want you to do what you think is right.’ So we ended up going in and we decided to shoot it both ways. We shot them doing all the frame-ups with their hands just in case I was wrong, and we shot every interaction authentically without the finger framing. And after editing it, I am glad that we took the new approach because it’s stronger not having had them do the frames.” (See Figures 6.5 and 6.6.)

Figure 6.5 The last frame of action from Zandrak’s Moodsnap promo. It contains the only actor frame-up with his fingers culminating in the representation of memory. (Courtesy of Zandrak.)

For Charles, projects shouldn’t be cemented in stone and it’s why it’s important to build a good relationship with a client. The Moodsnap example shows how a project can evolve. He says, “If you have a client that trusts you, and you have a good relationship about the philosophy behind what you are doing, they are probably going to be willing to take a panicked call at midnight the night before you’re shooting, saying, ‘I want to take a change in direction,’ and they might even be okay with it.” It’s also an example of the type of clients they like. “It’s this kind of relationships we are looking for,” Charles says, “and when the client came in and looked at the footage he was really happy with the shift in direction as well.”

Figure 6.6 Zandrak’s Moodsnap as it appears on an iPhone in the final moment of their promo. It contains a shot of the couple we see in their film. (Courtesy of Zandrak.)

After the synopsis, there’s the execution page (see Figure 6.7).

This explores their approach to capturing the feel or the sense of direction or style in which they want to take the work. “We talk about the way we want to capture the piece,” Charles says. “And in this case it was very much centered around the POV perspective, looking through the frames. We wanted to do a visual style where when they brought up their hands and did the frames, we would be actually seeing from their eyeballs through the frame to what they were seeing.” It revealed their visual style, but when it came to thinking about how to shoot it, Charles realized it wouldn’t work. “It was a cool visual style,” he explains, “but once again, it was something hard to incorporate organically that we couldn’t have predicted until we really got closer to the shoot.”

Figure 6.7 The pitch or proposal from Zandrak, includes an execution page. (Courtesy of Zandrak.)

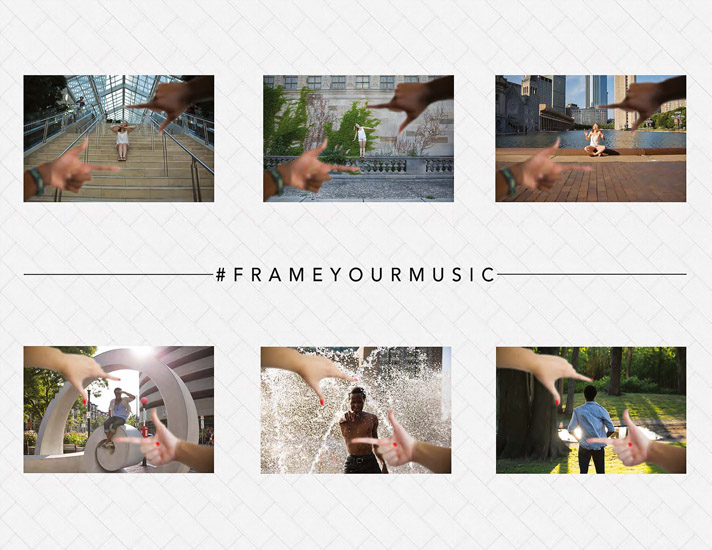

Ultimately, the pitch or proposal is a draft and it sets the tone, even if you don’t literally follow all of it when you execute it. “But this is what we pitched to him and he liked that, and we even made a page, called Mood.” (See Figure 6.8.)

The mood page is a visual way to set the tone of the work. “We went out and we shot frames, with Chris, the actor, and a friend of his and then we shot it through their hands so we could see what that would look like,” Charles explains. “It gave the client a visual reference for what those points of view shots would look like. And we even developed a bit of a campaign around the idea of framing the music, because you are literally framing your music. In the end, it’s something that didn’t hold up, but we did pitch it originally.”

Figure 6.8 Zandrak’s mood page from the Moodsnap pitch. (Courtesy of Zandrak.)

The budget provides a brief outline of the cost for the project (page not included for privacy purposes. See Zandrak’s Moodsnap Budget Estimate in Figure 6.10, below). The budget, Charles says, breaks out all the list items of what everything would cost. This is where you might add a note about the number of editing revisions allowed before additional charges to your client. There’s also a “future” page, where, he explains, “we talk about the continuation of our collaborative relationship and types of projects we could do that could continue to help promote the client’s brand and would give us continued work to exercise creativity” (see Figure 6.9).

Figure 6.9 The future, a page from Zandrak’s Moodsnap pitch. (Courtesy of Zandrak.)

The page for the future, Charles says, “Buttoned up the initial visual style that we saw in the beginning. We see the car on the first page. It’s a road trip and now we are ending on an empty road implying the future has in store but still along the same theme of a road trip. It took a lot of time to find images that contained little representations that matched our aesthetic, but I think it is little details like that that helps sell what you are doing.”

And it worked. The client approved it. “He had notes and thoughts about it,” Charles states, “but that was what it took for him to sign a contract, and say, ‘Let’s do this thing.’ And even though it evolved from there, it was just that initial starting point that we needed to really get him on board. And I think had we just sent him a Word document it wouldn’t have been as compelling and we wouldn’t have seemed as committed to it.”

There was no formal script for the shoot, rather Charles developed scenarios and developed the storyline as they shot. The final work, “Our Songs,” as seen on the client’s page is located at: http://moodsnap.fm.

Creating a Script for the Honors Program at NAU

To show the process of developing a script from keywords involving story intention, I include a project that I oversaw at Northern Arizona University for University Marketing. I led a team of students in the creation of a promotional video for NAU’s Honors Program. As we discussed possible story concepts with the director of the program, Wolf Gunnerman, how it would show off visually the different classes and activities, including livings spaces, outdoor adventures, classroom inter actions, community building, I knew we needed Zandrak involved somehow. I wanted Kyle Harper, the writer for Zandrak, the writer of “Still Life” and the Hasbro commercial. I got approval for a payment for Zandrak to cover the cost of the writing and talked to Kyle about it. He developed a short script. Gunnerman requested a few minor changes. Kyle revised it and it was approved.

The project began as an open discussion of intent and the development of keywords (following Stillmotion’s MUSE model). Marteen Cleary, Reed Robertson, and Mariah Soer (and later, Michael Kerbleski)—the student team for this project—developed the following keywords with me: Community, adventure, unique, and engaging. The University Honors Program revolves around honor, distinction, and community (http://nau.edu/honors/)—also were the video is embedded. The thrust and purpose of our project revolved around the fact that many potential incoming first-year students are turned off from the Honors Program due to the demands put on them from AP honors programs in high school. The university program is more fun, Gunnerman says. It’s about the unique class content, interactive participation in the classroom, and engaging in outdoor activities in some classes (such as experiencing art and creative writing at Vermillion Cliffs in northern Arizona). In addition, since the program focuses on leadership, teamwork, and interpersonal communication, many students with this skillset are offered jobs after graduating.

Reed came up with the idea that there should be a student who enrolled in the program from the beginning, show students in the different phases of classroom, housing, and outdoor activities, graduation, and then at a job. We developed this concept and called Kyle Harper at Zandrak, giving him the information we had developed. The questions involved intention and sharing the keywords and the purpose of the recruitment video, as explained above. He created the following script from our discussion (this version of the script includes minor changes requested from the client):

NAU Honors Video (Kyle Harper)

Note from Writer: The opening action/scene is only written in for context of how the professor starts speaking—obviously feel free to change it or just exclude it entirely. I have not included any other scene suggestions, so as to leave as much room for creativity from the students shooting the film. The speech itself, beginning at the VO, currently runs about 1:15 seconds. (Which should be just enough wiggle room for you to edit a 90-second spot comfortably.) If you would like an example reading, let me know!

Int. Classroom. Day

A class of COLLEGE FRESHMEN are milling about in a classroom while the PROFESSOR arranges some papers on his desk. The students are setting down their backpacks, settling into seats, chatting with their neighbors. The Professor casually addresses them.

PROFESSOR First day of class, welcome everyone! If you would please, grab your seats.

The students settle down in their seats, pencils, notebooks, and attentive smiles at the ready. The Professor looks out at all of them, considering. Then, he begins to speak.

PROFESSOR (Start of the voiceover)

What makes you a student?

Is it your desk? The notes you take? The tests you pass?

Maybe. But I think there’s more.

Outside of this classroom, you need more than your notebooks or papers to learn.

You find people and places that capture your imagination, causes that stir you to action, challenges that push you and excite you all at once.

Your goal isn’t just to know more, it’s to step outside the box, to do better.

And maybe even change your world in the process.

This makes you more than just students.

This makes you explorers and leaders, innovators and visionaries.

You are influencers and game-changers in the making.

All because you don’t let learning stop at the end of your textbook.

You are not students because you learn in this classroom, you are students because learning is everything you do with your life, and this will enrich you far more than anything I could ever offer you.

What will you discover this year?

What will you try that has never been tried before?

Who will you be afterwards?

(I imagine this would be an excellent place for a longer pause.)

I cannot wait for you to find out.

Welcome to real learning. Welcome to NAU Honors.

Notice how Kyle doesn’t utilize the formal script template. He is trained as a creative writer and you can see his technique of poetry informs his style, providing the project with a fresh approach. With the script in hand, we shot different angles of one of the Honors Program’s instructors, Kevin Ketchner, introducing himself to a class and interacting with students from his classroom on Sherlock Holmes. He improvised the opening dialogue and then we had him read the script. We edited the visuals around the words he performed. We also gathered trips outside the classroom, our team gathering footage in Mexico and northern Arizona, for example.

Some marketing films at NAU utilize improvised dialogue based on focused questions (similar to a documentary style)—very few projects use a scripted narration, but we felt this one could use the words and we wanted one of the teachers to do the performance rather than a hired professional performer. But as a part of the process, Director of Marketing Sandra Kowalski, who made a couple of minor changes to the script as well, said that she didn’t want a professor reading it—it’s a marketing tool for students and she wanted a student performing it (we changed the script to reflect this). We assigned Marteen, a student, to read the script, recording it line by line in a multi-hour recording session until we got the tone right. Furthermore, after the project was approved by Kowalski, Gunnerman sent it out to his team of professors and instructors and some of them gave feedback and additional changes were made (not every suggestion was taken, but there were a couple of changes made).

This example shows how different people with a stake in a project will require changes, but the original vision and feel of the project was never lost since we had held onto keywords, which evolved into Kyle’s script. The completed University Honors Program video is located on their homepage: http://nau.edu/honors.

Writing a BID or Production Budget Quote

Woody Biomass Project

The production budget quote—or bid—is tied to your cost of doing business, covered in Chapter 5. Be sure you’re meeting your financial need when you create a quote and base it around your day rate. (The Production Quote Form is online at http://kurtlancaster.com/contracts-and-forms/) This sample form was provided by Zandrak (see Table 6.1). The opening section provides the contact info for the production company and client. If needed (you will likely want to use it on larger productions), use the Film Project Budget Form online to lay out the entire budget and use it to fill in the estimated production costs in the bid.

Let’s walk through an example of a budget quote for a project that I submitted to Arizona State Forestry. (I’m leaving out personal contact info.) Patrick Rappold approached the School of Communication at NAU, wanting to develop a short documentary about the use of excess wood for word-burning power plants— it’s a way to use leftover wood parts and for forest thinning to help control potential wildfires. His division won a grant of $15,000 for the project, so that’s the non-negotiable budget.

Here’s a brief breakdown of each section:

- Preproduction: The planning stage which includes onsite pre-interviews, scouting locations, story development, storyboards, scripting, shot lists.

- Production: The actual time spent in the field shooting. I set it up for five days at $600 per day, which will cover two cameras and a sound person.

- Deliverables: What file are you delivering? Is it a DVD or web link, a memory stick with a ProRes file? In this case it will be a web file for streaming.

- Editorial: Editing of the film. I include six days of editing plus up to three revisions (which is what you would put in the Production Agreement).

- Audio postproduction: Mixing audio and fixing audio issues. In this case, I roll the costs of audio postproduction into editorial, since I will do the audio mix myself—you would put in the cost of an outside postproduction studio for one day of work (anywhere from $500–1,000 would be typical).

- General and Administrative: Covers the cost of your time doing emails, contacts, communication with the client, setting up meetings, and so forth. I’m also rolling in the cost of hiring student production assistants for the shoot into this administrative cost.

- Travel: Include miles for car travel, or train or plane fare, as well as per diem and hotel costs.

- Notes: Rewrite the notes as needed.

Table 6.1 Production Budget Quote for Woody Biomass Utilization in Arizona Documentary

| Production Co: Kurt Lancaster | Client: Arizona State Forestry |

| Address: NAU School of Communication PO Box 5619 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 | Contact: Patrick Rappold Wood Utilization & Marketing Specialist |

| Telephone: | Product: Website file for streaming |

| Date: July 28, 2015 | Production days: 5 |

| Exec. Producer: Kurt Lancaster | Timeline: 10 months |

|

|

|

| Estimated Production Costs | Estimate |

| Preproduction (onsite pre-interviews, scouting locations, story development) | $3,000 |

| Production (5 days) | $6,000 |

| Deliverables | $100 |

| Editorial postproduction | $3,000 |

| Audio postproduction (in editorial) | $0 |

| General & Administrative (including production assistant and university overhead costs) | $2,000 |

| Travel | $900 |

| Total | $15,000 |

|

|

|

|

Notes This quote estimate was prepared for Arizona State Forestry under the pretense that Kurt Lancaster with NAU’s School of Communication will produce one spot based on preapproved storyboards and script, to come in at a running time of 5–8 minutes, for public promotional use. This includes preproduction, 5 days of production, a production crew and equipment package. Kurt Lancaster with the School of Communication will provide postproduction services, including editorial, audio mixing, stock music, and finishing. Kurt Lancaster will act as the client’s point of contact throughout all phases of the production through final deliverables. This is a rough quote and was made under the assumption that Kurt Lancaster with the School of Communication will manage the project to completion, consulting with client, and that client will have the option of being on site for production and postproduction. The client will have three revisions of pictures for editorial. Upon completion of the shoot, we will deliver the final video as a QuickTime ProRes 422 file and a file for the web. Additional deliverable file types and still frames for promotional use are available upon request. |

|

This form is key in laying out the initial expectations for the client. Once this is agreed upon, you would issue a production agreement contract for signature.

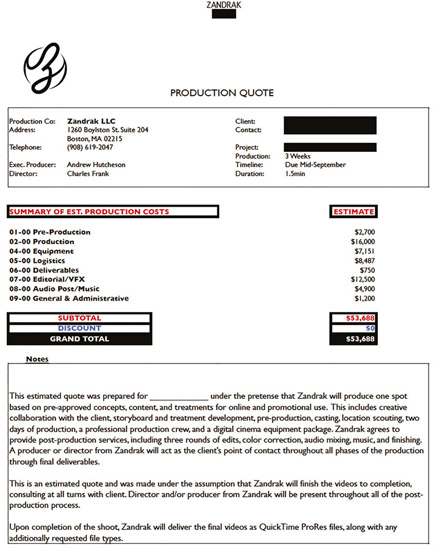

Zandrak’s Moodsnap Budget Estimate

The budget below in Figure 6.10 reveals the estimate that executive producer Andrew Hutcheson delivered to their client (the final budget is confidential). Note that personal information has been blacked out. This is provided to show what a higher budget estimate looks like at a professional level.

Figure 6.10 Zandrak’s budget estimate for Moodsnap video, “Our Songs.” (Courtesy of Zandrak.)

Zandrak’s estimated budget for the Moodsnap promotional film includes a specific breakdown of preproduction; production; equipment rental; logistics; deliverables; editorial and effects; audio postproduction work, including music; and administrative costs. The production project is set to revolve around a three-week shoot.

Worksheet: Developing a Pitch, Treatment, and Bid

- Who is your client?

- What is their need and how can you solve their problem?

- Research the client:

- Websites

- News stories and magazines

- Existing interviews

- Interview the client(s) in person, if possible, and note what they really need—you will develop keywords from these notes to discover their needs and how you can solve their problem.

- Stillmotions’s four Ps and five keywords (or, even better, use the full worksheets if you sign up for MUSE)

- People

- Place

- Purpose (including keywords)

- Plot

- Write a bid proposal. Use a. or b. below.

- Here’s what Stillmotion uses, modify as needed:

- Concept: A brief overview of our concept for the project, to be expanded upon later if necessary as a treatment.

- Preproduction: Casting, pre-interviewing, scouting, and learning the story.

- Production: Days required for production, and a list of resources—the director, the DP, a second camera, major pieces of gear should be listed.

- Postproduction: A list of the deliverables— “one 3–5 minute film in HD, web ready,” how many rounds of editing is required, color correction, sound mixing. . . . all these things you should mention briefly.

- Soundtrack: Here you might want to give them some options with the estimated costs for licensing music. A song with a one-year lifespan is going to be cheaper than a song with a perpetual lifespan, and that’s a choice they’ll have to make. We list the cost for both the one-year and the perpetual lifespan, usually indicating the cost for anywhere from 1–10 songs.

- Travel: “We’ll make all the travel plans . . . you give us this much money.”

- Rights: A brief statement of the ownership/ rights to the material, and that we reserve the right to show the material (when applicable—this isn’t always the case).

- Project Estimate: No fluff—just the estimated cost of the entire project. (Reference the Production Quote Form).

- A Final Note: We don’t want the last thing on our bid to be a big dollar sign and nothing more. Here we’ll make a note about why we’re excited to work with them, and why we believe in the project.

- Zandrak uses a visual proposal that typically includes:

- Title page (based on an image)

- Synopsis (short and poetic)

- Execution (how they will approach the project; a description of the visual style)

- Mood page (a series of stills that show off their visual style and approaches—this should reinforce the written execution in a visual way)

- Budget (what will it cost?)—attach or insert the full Production Quote Form here.

- Here’s what Stillmotion uses, modify as needed:

- Submit the above bid, including the production quote.

- Accepted as is.

- Make additional changes negotiated with the client.

- Submit Production Agreement contract for signature (forms online at http://kurtlancaster.com/contracts-and-forms).

- Go into full preproduction and develop a formal treatment, script, and storyboards.

- Submit treatment, script, and storyboards (see Stillmotion’s Creative Brief, online, http://kurtlancaster.com/contracts-and-forms/).

- Accepted as is.

- Make additional changes negotiated with the client.

- Submit initial invoice for first third of payment as stipulated in the contract.

- Go into production.

- Submit second invoice for second payment as stipulated in the contract.

- Go into postproduction.

- Client reviews the final cut of film.

- Make additional changes as requested by client.

- Repeat up to contract limit (usually three).

- Deliver final product to client.

- Submit final invoice for final payment as stipulated in the contract.