Chapter 8

Main financial statement: The statement of cash flows

‘Cash is King. It is relatively easy to “manufacture” profits but creating cash is virtually impossible.’

UBS Phillips and Drew (January 1991), Accounting for Growth, p. 32.

Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter you should be able to:

- Explain the nature of cash and the statement of cash flows.

- Demonstrate the importance of cash flow.

- Investigate the relationship between profit and cash flow.

- Outline the direct and indirect methods of the statement of cash flows preparation.

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Chapter Summary

- Cash is key to business success.

- Cash flow is concerned with cash received and cash paid, unlike profit which deals with income earned and expenses incurred.

- Reconciling profit to cash flow means adjusting for movements in working capital and for non-cash items, such as depreciation.

- Large companies provide a statement of cash flows as the third major financial statement.

- Sole traders, partnerships and small companies may, but are not required to, prepare a statement of cash flows.

- The two ways of preparing a statement of cash flows are the direct and the indirect methods.

- Most companies use the indirect method of preparing a statement of cash flows.

- Listed companies use a different format than other business organisations.

Introduction

Cash is king. It is the essential lubricant of business. Without cash, a business cannot pay its employees’ wages or pay for goods or services. As Real-World View 8.1 shows, at its most extreme, this can lead to the failure of a business. A business records cash in the bank account in the books of account. Small businesses may sometimes prepare a statement of cash flows directly from the bank account. More usually, however, the statement of cash flows is prepared indirectly by deducing the figures from the income statement and the statement of financial position. The statement of cash flows, at its simplest, records the cash inflows and cash outflows classified under certain headings such as cash flows from operating (i.e., trading) activities. All companies (except small ones) must prepare a statement of cash flows in line with financial reporting regulations. However, some sole traders, partnerships and smaller companies also provide them, often at the request of their bank. As Real-World View 8.2 shows, banks are well aware of the importance of cash. As well as preparing the statement of cash flows on the basis of past cash flows, businesses will continually monitor their day-to-day cash inflows and outflows. Statements of cash flows essentially record what has happened over the reporting period. As we shall see in Chapter 17, companies also prepare cash budgets which look to the future. Cash management, therefore, concerns the past, present and future activities of a business.

Cash Bloodbath

With last week's collapse of Boo.com – the first big liquidation of a dot.com company in Europe – the internet gold rush has taken on the appearance of a bloodbath. The company's principal failing – and there were many, it was burning cash at a rate of $1m a week – was to forget that in the new economy the old rules still apply.

Source: Accountancy Age, 25 May 2000, p. 26.

Cash Flow

Bankers do know about cash flow. They have to live with it on Friday, every Friday, in any number of companies up and down the country. Where there is insufficient cash to pay the wages, really agonising decisions result. Should the company be closed, with all the personal anguish it will cause, or should it be allowed to limp on, perhaps to face exactly the same agonising dilemma in as little as a week's time?

Source: B. Warnes (1984), The Genghis Khan Guide to Business, Osmosis Publications, London, p. 6.

Importance of Cash

Cash is the lifeblood of a business. Cash is needed to pay the wages, to pay the day-to-day running costs, to buy inventory and to buy new property, plant and equipment. The generation of cash is, therefore, essential to the survival and expansion of businesses. Money makes the world go round! In many ways, the concept of cash flow is easier to understand than that of profit. Most people are more familiar with cash than profit. Cash is, after all, what we use in our everyday lives. At its most stark, if a business runs out of cash it will not be able to pay its trade payables and it will cease trading. As Jack Welch, a successful US businessman, has said, ‘There's one thing you can't cheat on and that's cash and Enron didn't have any cash for the last three years. Accounting is odd, but cash is real stuff. Follow the cash’ (The Guardian, 27 February 2002, p. 23). Ken Lever, a member of the UK's Accounting Standards Board agrees (Accountancy Age, 24 February 2011, p. 5). Cash flow is the key. ‘A lot of businesses see cash as an afterthought. There is a tendency to get sidetracked by accounting metrics.’

It is far easier to manipulate profit than it is to manipulate cash flow. This is highlighted by Real-World Views 8.3 and 8.4. In Real-World View 8.3, Phillips and Drew, a firm of city fund managers (now called UBS Global Management), basically state that cash is essential to business success.

Importance of Cash I

In the end, investment and accounting all come back to cash. Whereas “manufacturing” profits is relatively easy, cash flow is the most difficult parameter to adjust in a company's accounts. Indeed, tracing cash movements in a company can often lead to the identification of unusual accounting practices. The long term return of an equity investment is determined by the market's perception of the stream of dividends that the company will be able to pay. We believe that there should be less emphasis placed on the reported progression of earnings per share and more attention paid to balance sheet movements, dividend potential and, most important of all, cash.

Source: UBS Phillips and Drew (January 1991), Accounting for Growth, p. 1.

This was as true in 1991, as it was in 2011, as Real-World View 8.4 shows.

Importance of Cash II

Even more important than earnings coverage, though, is free cash flow coverage. Whereas earnings are in some part an accounting fiction, free cash flow is cold, hard fact. Free cash flow can be used for real purposes, including paying debts, investing in new capacity and paying dividends. Therefore, we tried to pick out companies whose free cash flow had improved or was stable over recent years – as well as those in the opposite situation.

Source: D.M. Hand, Die hard dividends, Investors Chronicle, 21–27 October 2011, p. 24. Financial Times Ltd.

HELPNOTE

HELPNOTE

Free cash flow is defined as:

‘Cash flow from operations after deducting interest, tax, preference dividends and ongoing capital expenditure, but excluding capital expenditure associated with strategic acquisitions and/or disposals and ordinary share dividends’ (CIMA, 2009, Official Terminology).

Context

The statement of cash flows is the third of the key financial statements which medium and large companies provide. It summarises the company's cash transactions over time. At its simplest, the cash flow is related to the opening and closing cash balances:

![]()

Cash inflows are varied, but may, for example, be receipts from sales or interest from a bank deposit account. Cash outflows may be payments for goods or services, or for capital expenditure items such as motor vehicles.

All large companies are required to provide a statement of cash flows. There are two methods of preparation. The first is the direct method, which categorises cash flow by function, for example receipts from sales. A statement of cash flows, using the direct method, can be prepared from the bank account and is the most readily understandable. The second method is the indirect method. This uses a ‘detective’ approach. It deduces cash flow from the existing statements of financial position and income statement and reconciles operating profit to operating cash flow. The statement of cash flows, using the indirect method, is not so readily comprehensible. Unfortunately, this is the method most often used.

Yes, But What Exactly is Cash?

Cash is cash! However, there are different types of cash, such as petty cash, cash at bank, bank deposit accounts, or deposits repayable on demand or with notice. How do they all differ?

The basic distinction is between cash and bank. However, the terms are often used loosely and interchangeably. Cash is the cash available. In other words, it physically exists, for example, a fifty pound note. Petty cash is money kept specifically for day-to-day small expenses, such as purchasing coffee. Cash at bank is normally kept either in a current account (which operates via a cheque book for normal day-to-day transactions) or in a deposit account (basically a store for surplus cash). The term cash and cash equivalents is often used to refer to cash at bank and that held in short-term (say up to 30 days) deposit accounts. Deposits repayable on demand are very short-term investments which can be repaid within one working day. Deposits requiring notice are accounts where the customer must give a period of notice for withdrawal (for example, 30 days).

Cash and the Bank Account

As we saw in Chapter 4, cash is initially recorded in the bank account. In large businesses, a separate book is kept called the cash book. Debits are essentially good news for a company in that they increase cash in the bank account, whereas credits are bad news in that they decrease cash in the bank account. From the bank account it is possible to prepare a simple statement of cash flows.

Cash Inflows and Outflows

What might be some examples of the main sources of cash inflow and outflow for a small business?

| Cash Inflow | Cash Outflow |

| Cash from customers for goods | Payments to suppliers for goods |

| Interest received from bank deposit account | Payments for services, e.g., telephone, light and heat |

| Cash from sale of property, plant and equipment | Repay bank loans |

| Cash introduced by owner | Payments for property, plant and equipment, e.g., motor vehicles |

| Loan received | Interest paid on bank loan |

Let us take the example once more of Gavin Stevens’ bank account (see Figure 8.1). As Figure 8.1 shows, we have essentially summarised the figures from the bank account and reclassified them under certain headings.

For sole traders and partnerships, there is no regulatory requirement for a statement of cash flows in the UK. Small companies are also exempt. Many organisations do, nevertheless, prepare one. UK non-listed companies are regulated by an accounting standard, Financial Reporting Standard 1. However, UK listed companies, like all European listed companies, follow International Accounting Standard IAS 7. The objective of this standard is to require the provision of information about the historical changes in cash and cash equivalents of an entity by means of a statement of cash flows which classifies cash flows during the period as operating, investing and financing activities. The statement of cash flows is a primary financial statement and ranks along with the statement of financial position and income statement. These standards lay down certain main headings for categorising cash flows (see Figure 8.2).

In Appendix 8.1, the main headings for the cash flow statement (note it is called the cash flow statement rather than the statement of cash flows) as required by the UK's accounting standards are given. This can be used by sole traders, partnerships and some non-listed companies.

We use three headings for listed companies (see Figure 8.2 on page 215): (1) Cash flows from operating activities (which covers flows from operating activities and taxation); (2) Cash flows from investing activities (which covers capital expenditure and financial investment, acquisitions and disposals, interest received and dividends received); and (3) Cash flows from financing activities. Unfortunately, these headings are very cumbersome and often lack transparency.

The details of IAS 7 are well summarised in Real-World View 8.5 by Paul Klumpes and Peter Welch.

Cash Flow Statements

According to the International Accounting Standards Committee Foundation's Technical Summary of IAS 7: ‘The objective of this standard is to require the provision of information about the historical changes in cash and cash equivalents of an entity by means of a statement of cash flows which classifies cash flows during the period as operating, investing and financing activities.’

Summarising the three cashflow categories:

- Operating: principal revenue-producing activities of the entity.

- Investing: acquisition and disposal of long-term assets and other investments (including subsidiaries).

- Financing: activities that result in changes in the size and composition of equity and borrowings.

Crucially, IAS 7 allows two options for the reporting of operating activities:

- Direct method: major classes of gross cash receipts and payments are disclosed.

- Indirect method: profit and loss adjusted for the effects of non-cash transactions, any deferrals/accruals of operating cashflows and any income and expense items associated with investing or financing cashflows.

The operating section of a bank's cashflow statement is more complex than that of a non-financial firm. A bank's core services – taking in deposits and other funds and using those funds to make loans and investments – are themselves cashflows. These are also captured in the operating segment as operating asset and liability flows. In broad terms, a bank's operating cashflow is therefore made up of two main components:

- The adjustment of profit (normally profit before tax) for non-cash items, tax paid, etc.

- The operating asset and liability flows – the asset-related movements in loans and investments, and liability-related movements in deposits and wholesale funding such as debt securities.

Despite their importance to understanding a bank's financial health, all the UK and Eurozone banks we surveyed were using the indirect method to report their operating asset and liability flows on a net basis. Yet in most cases, the net change can already be calculated or estimated, by comparing the value of the item (for example, loans and advances to customers) in the end period balance sheet with its value in the preceding period balance sheet. This leaves the cashflow statement communicating little new information.

Source: Paul Klumpes and Peter Welch, Call for Clarity, Accountancy Magazine, October 2009, pp. 34–5. Copyright Wolters Kluwer (UK) Ltd.

Relationship between Cash and Profit

Cash and profit are fundamentally different. In essence, cash flow and profit are based on different principles. Cash flow is based on cash received and cash paid (see Figure 8.3). By contrast, profit is concerned with income earned and expenses incurred.

In a sense, the difference between the two merely results from the timing of the cash flows. For example, a telephone bill owing at the year end is included as an accrued expense in the income statement, but is not counted as a cash payment. However, next year the situation will reverse and there will be a cash outflow, but no expense.

An important difference between profit and cash flow is depreciation. Depreciation is a non-cash flow item. The related cash flows occur only when property, plant or equipment is bought or sold. Real-World View 8.6 demonstrates this.

Cash Loss vs. Stated Loss

As always, there is the need to distinguish between a stated loss, per the profit and loss account [income statement] and a cash loss. One company the author handled was running at an apparently frightening loss of £25,000 per month, but on closer examination there was not too much to worry about. It had a £30,000 monthly depreciation provision. It was in reality producing a cash-positive profit of £5,000 per month. It had years of life before it. This gave all the time needed to get the operation right.

Source: B. Warnes (1984) The Genghis Khan Guide to Business, Osmosis Publications, London, p. 63.

Figure 8.4 shows how some common items are treated in the income statement and statement of cash flows. Some items, such as sale of goods for cash, appear in both. However, amounts owing, such as a telephone bill, appear only in the income statement. By contrast, money received from a loan only affects the statement of cash flows.

Figure 8.4 Demonstration of How Some Items Affect the Income Statement and Some Affect the Statement of Cash Flows

Sometimes, a business may make a profit, but run out of cash. This is called overtrading and happens especially when a business starts trading.

Overtrading, Cash Flow vs. Profit

A company, Bigger is Better, doubles its revenue every month.

It pays its purchases at once, but has to wait two months for its customers to pay for the revenue. The bank, which has loaned £10,000, will close down the business if it is owed £50,000. What happens?

The result: Bye-bye, Bigger is Better. Even though the business is trading profitably, it has run out of cash. This is because the first cash is received in month 3, but the cash outflows start at once.

Preparation of Statement of Cash Flows

In this section, we present the two methods of preparing a statement of cash flows (the direct and indirect methods). In Figure 8.5 and Appendix 2, a statement of cash flows is prepared for a sole trader using the direct method, which classifies operating cash flows by function or type of activity (e.g., receipts from customers). In Figure 8.5 the statement of cash flows is prepared using IFRS while Appendix 8.2 illustrates UK GAAP. In essence, this resembles the statement of cash flows for Gavin Stevens in Figure 8.1. We assume a bank has requested a statement of cash flows and that it is possible to extract the figures directly from the company's accounting records. Figure 8.6 then compares the direct and indirect methods of preparing the statement of cash flows. In Figure 8.7 we then look at some of the adjustments made to profit to arrive at cash flow. This is followed with an illustrative example in Figure 8.8, Collette Ash. We then present the statement of cash flows for a company using the more conventional indirect method used by most companies in Figure 8.9, following IFRS format. In Appendix 8.3, we prepare the statement of cash flows using UK GAAP. In this case, we derive the operating cash flow from the income statement and the statement of financial position.

Direct Method

This method of preparing statements of cash flows is relatively easy to understand. However, in practice it is used far less than the indirect method. It is made of functional flows such as payments to suppliers or employees. These are usually extracted from the cash book or bank account. Figure 8.5 demonstrates the direct method using IFRS format.

Figure 8.5 Preparation of a Sole Trader's Statement of Cash Flows Using the Direct Method Using IFRS Format

We used the headings in Figure 8.2 which relate to the presentation of the statement of cash flows using IFRS. We use this as the main presentational format for ease of understanding. However, Appendix 8.2 gives the traditional format using UK Accounting Standards. The net cash inflow from operating activities represents all the cash flows relating to trading activities (e.g., buying or selling goods). By contrast, returns on investments and servicing of finance deals with interest received or paid, resulting from money invested or money borrowed. Capital expenditure and financial investment are concerned with the cash spent on, or received from, buying or selling property, plant or equipment. Finally, financing represents a loan paid into the bank.

Profit and Positive Cash Flow

If a company makes a profit, does this mean that it will have a positive cash flow?

No! Not necessarily. A fundamental point to grasp is that if a company makes a profit this means that its assets will increase, but this increase in assets will not necessarily be in the form of cash. Assets other than cash may increase (e.g., property, plant and equipment, inventory or trade receivables) or liabilities may decrease. This can be shown by a quick example. Noreen O. Cash has two assets: inventories £25,000 and cash £50,000. Noreen makes a profit of £25,000, but invests it all in inventories. We can, therefore, compare the two statements of financial position.

There is a profit, but it does not affect cash. The increase in profit is reflected in the increase in inventories.

From Richard Hussey's statement of cash flows it is clear that cash has increased by £66,400. However, the statement also clearly shows the separate components such as a positive operating cash flow of £59,150. By looking at the statement of cash flows, Richard Hussey can quickly gain an overview of where his cash has come from and where it has been spent. The principles underlying the direct method of preparation are similar to those used in the construction of a cash budget (see Chapter 17).

Indirect Method

The most common method of preparing the statement of cash flows is the indirect method. This method, which can be more difficult to understand than the direct method, has three steps.

- First, we must adjust profit before taxation to arrive at operating profit.

- Second, we must reconcile operating profit to operating cash flow by adjusting for changes in working capital and for other non-cash flow items such as depreciation. By adjusting the operating profit to arrive at operating cash flow, we effectively bypass the bank account. Instead of directly totalling all the operating cash flows from the bank account, we work indirectly from the figures in the income statement and the opening and closing statements of financial position. This reconciliation is done either as a separate calculation or in the statement of cash flows.

- Third, we can prepare the statement of cash flows.

These steps are outlined in Figure 8.6 and the direct and indirect methods are compared.

We will now look in more detail at the first two steps. Figure 8.7 summarises these adjustments and then Figure 8.8, Collette Ash, illustrates them. We then work through a full example, Any Company plc, in Figure 8.9. Figure 8.9 uses the IFRS format while in Appendix 8.3 we present the statement of cash flows using the more traditional UK format. Essentially, the method of preparation in the two figures is identical, but the presentation differs.

1. Calculation of Operating Profit by Adjusting Profit before Taxation

In the indirect method, we need to calculate operating cash flow (i.e., net cash flow from operating activities). To do this we need to first calculate operating profit so that we can reconcile operating profit to operating cash flow. Operating profit is calculated by adjusting profit before taxation to operating profit. The profit before tax figure must be adjusted by adding interest paid and deducting interest received. (Strictly, these items are called interest payable and interest receivable, for simplicity we call them in this section interest paid and interest received: see Figure 6.5 for an explanation of this.) These items can, under IAS 7 be treated as (i) either operating activities or (ii) interest paid as a financing activity and interest received as an investing activity. In either case they must be separately disclosed. In this book I treat them as financing and investing flows respectively, as that seems most logical. Thus, they will appear in our statement of cash flows as follows: interest received under cash flows from investing activities and interest paid under cash flows from financing activities. For listed companies, this adjustment is recorded under the heading Cash Flows from Operating Activities.

2. Reconciliation of Operating Profit to Operating Cash Flow

It is possible to identify two main types of adjustment needed to adjust operating profit to operating cash flow: (i) working capital adjustments and (ii) non-cash flow items, such as depreciation. It is important to emphasise that we need to consider operating cash flow and operating profit. The term ‘operating’ is used in accounting broadly to mean trading activities such as buying or selling goods or services. For listed companies, we start from profit before taxation not operating profit. Taxation paid is also deducted under Cash Flow from Operating Activities.

(i) Working Capital Adjustments Effectively, working capital adjustments represent short-term timing adjustments between the income statement and statement of cash flows. They principally concern inventory, trade receivables and trade payables. Essentially, an increase in inventory, trade receivables or prepayments (or a decrease in trade payables or accruals) means less cash flowing into a business for the current year. For example, when trade receivables increase there is a delay in receiving the money. There is thus less money in the bank. By contrast, a decrease in inventory, trade receivables or prepayments (or an increase in trade payables or accruals) will mean more cash flowing into the business.

(ii) Non-Cash Flow Items Two major items are depreciation and profit or loss on the sale of property, plant and equipment. These two items are recorded in the income statement, but not in the statement of cash flows. Depreciation (which has reduced profit) must be added back to profit to arrive at cash flow. By contrast, profit on sale of property, plant and equipment (which has increased profit) must be deducted from profit to arrive at Operating Cash Flow. Cash actually spent on purchasing property, plant and equipment or received from selling property, plant and equipment is included for listed companies under Cash Flows from Investing Activities in the statement of cash flows.

Figure 8.7 provides examples of both working capital and non-cash flow adjustments.

Figure 8.8, Collette Ash, on the next page now demonstrates the first two steps (calculation of operating profit and reconciliation of operating profit to operating cash flow). The increases or decreases in working capital items are established by comparing the individual current assets and current liabilities in the opening and closing statement of financial position. By contrast, the non-cash flow items (depreciation and profit on sale of property, plant and equipment) are taken from the income statement.

In straightforward cases this can be done in the statement of cash flows itself. Otherwise, as here, it can be done separately and the net figure, in this case £100,950, is taken to the statement of cash flows.

Figure 8.9 Preparation of the Statement of Cash Flows of Any Company plc using the Indirect Method Using IFRS

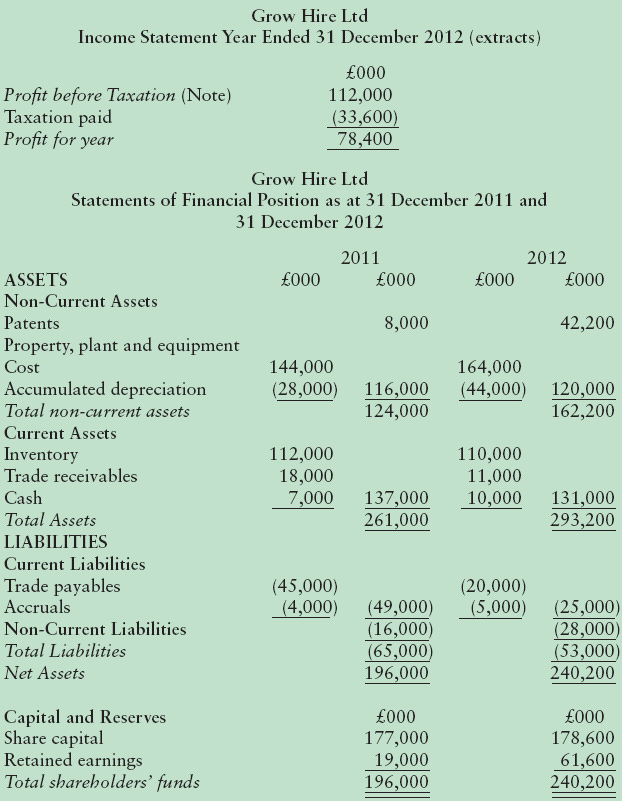

The three-stage process is now illustrated in Figure 8.9, which shows the calculation of a statement of cash flows for Any Company Ltd. The income statement and statement of financial position are provided. This is done by following IFRS. A statement of cash flows prepared under UK GAAP is recorded as Appendix 8.2. Then steps 1–3 which follow show how a statement of cash flows would be prepared using the indirect method.

An example of a statement of cash flows for AstraZeneca, a UK listed company, is given in Company Snapshot 8.1. There is also a statement of cash flows for Manchester United prepared under UK GAAP in Appendix 8.3. This has a very different format from the format of AstraZeneca that is prepared under IFRS.

Statement of Cash Flows for AstraZeneca, a Limited Company

Source: AstraZeneca plc, Annual Report and Form 20-F Information 2009, p. 127.

All the adjusted figures, therefore, involved comparing the two statements of financial position or taking figures directly from the income statement. In Figures 8.8 and 8.9, the taxation in the income statement was assumed to be the amounts paid. This will not always be so. Where this is not the case, it is necessary to do some detective work to arrive at cash paid! This is illustrated for tax paid in Figure 8.10.

Sometimes there may be cases where a dividend has been declared, but not paid during the year. In this case, one would do a similar exercise. However, given the rarity of this, it is not considered here in detail.

Essentially, we find the total liability by adding the amount owing at the start of the year to the amount incurred during the year recorded in the income statement. If we then deduct the amount owing at the end of the year, we arrive at the amount paid.

In Company Snapshot 8.2, J.D. Wetherspoon's 2010 statement of cash flows is presented. We can see that in 2010 there was a cash inflow from operating activities of £110.4 million. There was also a net investment in new pubs of £53.8 million (under cash flows from investing activities). Finally, Wetherspoon financed its operations mainly by bank loans of £87.6 million. Overall, Wetherspoon's cash increased by £2.5 million. Wetherspoon also reports its free cash flow (£71.3 million). Essentially, this is a company's cash flow from ongoing activities excluding financing. Cash flow statements can thus provide important insights into a business's inflows and outflows of cash.

Statement of Cash Flows for J.D. Wetherspoon plc

J D Wetherspoon plc, company number: 1709784

Source: J.D. Wetherspoon plc, Annual plc Report and Accounts 2010, p. 11.

Most companies comment on their cash flow in their annual reports. Sainsbury's, for example, summarises and comments on its cash flow activities in Company Snapshot 8.3.

Cash Flows from Operating Activities

Net debt and cash flow

Sainsbury's net debt as at 20 March 2010 was £1,549 million (March 2009: £1,671 million), a reduction of £122 million from the 2009 year-end position. The reduction was driven by the cash generated from the capital raised in June 2009 and strong operational cash flows, including another good working capital performance, offset by capital expenditure on the acceleration of the store development programme and outflows for taxation, interest and dividends. The resolution of a number of outstanding items contributed to a lower tax payment than in 2008/09, and interest payments benefited from lower interest rates on inflation linked debt as a result of a lower RPI than last year.

Sainsbury's expects year-end net debt to increase to around £1.9 billion in 2010/11, in line with its increased capital expenditure from the plan to deliver 15 per cent space growth in the two years to March 2011.

Sainsbury's has continued to manage working capital closely and cash generated from operations includes a further year-on-year improvement in working capital of £92 million. This has been achieved through tight management of inventories, which are up less than two per cent on last year, and continued improvement of trade cash flows.

Source: J. Sainsbury plc, Annual Report 2010, p. 19. Reproduced by kind permission of Sainsbury's Supermarkets Ltd.

Conclusion

Cash and cash flow are at the heart of all businesses. Cash flow is principally concerned with cash received and cash paid. It can thus be contrasted with profit which is income earned less expenses incurred. Cash is initially entered into the bank account or cash book. Companies usually derive the statement of cash flows from the income statement and statements of financial position, not the cash book. This is known as the indirect method of cash flow preparation. The statement of cash flows, after the income statement and the statement of financial position, is the third major financial statement. As well as preparing a statement of cash flows based on past cash flows, managers will constantly monitor current cash flows and forecast future cash flows. Cash is much harder to manipulate than profits. ‘Accounting sleight of hand might shape profits whichever way a management team desires, but it is hard to deny that a cash balance is what it is. No more, no less’ (E. Warner, The Guardian, 16 February 2002, p. 26).

Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions

Questions with numbers in blue have answers at the back of the book.

Numerical Questions

Numerical Questions

These questions are designed to gradually increase in difficulty. Questions with numbers in blue have answers at the back of the book. For consistency and ease of understanding, students should use the format required under International Reporting Standards for all questions whether they relate to sole traders, partnerships or companies.

Appendix 8.1: Main Headings for the Cash Flow Statement (Statement of Cash Flows) for Sole Traders, Partnerships and some Non-Listed Companies under UK GAAP

Notes:

1. Where cash flow is positive we use the term net cash inflow. Where it is negative we use net cash outflow.

2. This item mainly applies to groups of companies. They are outside the scope of this chapter.

3. For simplification, this item is not incorporated into any of the examples.

Appendix 8.2: Preparation of a Sole Trader's Cash Flow Statement Using the Direct Method Using UK Format

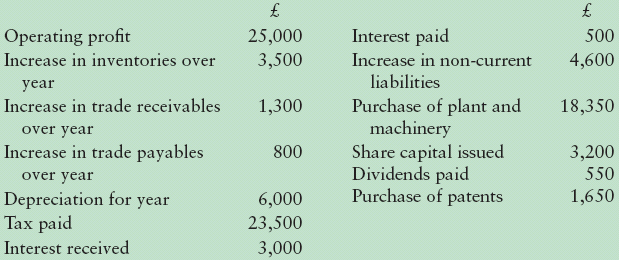

You have extracted the following aggregated cash figures from rhe accounting records of Richard Hussey, who runs a book shop. The bank has requested a cash flow stmement. Prepare Hussey's cash flow statement for year ended 31 December 2012.

Appendix 8.3: Preparation of the Cash Flow Statement of Any Company Ltd using the Indirect Method Using UK GAAP

To ease understanding, we use IFRS terminology rather than that permitted under UK GAAP.

Note:

This is after having added interest received of £15 to profit and having deducted interest paid of £8 from profit.

Notes:

1. There are no disposals of property, plant and equipment. Therefore, the increase in property, plant and equipment between 2011 and 2012 are purchases of property, plant and equipment.

2. Taxation in the income statement equals the amounts actual paid. This will not always be so.

3. Dividends paid for the year were £20,000.

Step 1: Calculation of Operating Profit

We need first to adjust net profit before taxation (£150,000) taken from profit and loss account, by adding back interest paid (£8,000) and deducting interest received (£15,000). These items are investment not operating flows. This is because we wish to determine operating or trading profit. Thus:

Step 2: Reconciliation of Operating Profit to Operating Cash Flow

This involves taking the company's operating profit and then adjusting for:

(i) Movement in working capital (e.g., increase or decrease in inventory, trade receivables, prepayments, trade payables and accruals).

(ii) Non-cash flow items such as depreciation, and profit or loss on sale of property, plant and equipment.

(1) Represents increases, or decreases, in the current assets and current liabilities sections between the two statements of financial position (i.e., movements in working capital).

(2) Difference in accumulated depreciation in the two statements of financial position represents depreciation for year (i.e., represents a non-cash flow item).

Step 3: Cash Flow Statement year Ended 31 December

This involves deducing the relevant figures in the cash flow statement by using the existing figures from the income statement and the opening and closing statements of financial position. We start from net cash inflow calculated in Step 2.

Notes:

1. Figure from income statement

2. Represents increase or decrease from statement of financial position

Some explanatory help:

1. Operating profit is adjusted for interest paid and interest received, then both are included under returns on investment and servicing of finance. In a listed company under IFRS we have included interest paid under financing flows and interest received under investing flows.

2. There are six headings recorded here rather than three using IFRS.

3. Depreciation is a non-cash flow item.

4. Taxation paid is recorded under taxation not under operating activities as per a listed company.

Appendix 8.4: Example of Statement of Cash Flow (Cash Flow Statement) Using UK GAAP (Manchester United Ltd)

Consolidated cash flow statement

Source: Manchester United Ltd, Annual Report and Financial Statements for the year end 30 June 2009, p. 13.

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

REAL-WORLD VIEW 8.1

REAL-WORLD VIEW 8.1 PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 8.1

PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 8.1

COMPANY SNAPSHOT 8.1

COMPANY SNAPSHOT 8.1