Chapter 10

Regulatory and conceptual frameworks

‘Regulation is like salt in cooking. It's an essential ingredient – you don't want a great deal of it, but my goodness you'd better get the right amount. If you get too much or too little you'll soon know.’

Sir Kenneth Berrill, Financial Times (6 March 1985), The Book of Business Quotations (1991), p. 47.

Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter you should be able to:

- Outline the traditional corporate model.

- Understand the regulatory framework.

- Explain corporate governance.

- Understand the conceptual framework.

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Chapter Summary

- Directors, auditors and shareholders are the main parties in the traditional corporate model.

- The regulatory framework provides a set of rules and regulations for accounting.

- At the international level, the International Accounting Standards Board provides a broad regulatory framework of International Accounting Standards. This applies to all European listed companies, including UK companies.

- In the UK, the two main sources of regulation are the Companies Acts and accounting standards.

- Financial statements must give a true and fair view of the financial position and performance of the reporting entity.

- The UK accounting standards-setting regime operates under the Financial Reporting Council. It consists of the Codes and Standards Committee, the Accounting Council, the Audit and Assurance Council and the Financial Reporting Review Panel.

- Corporate governance is the system by which companies are directed and controlled.

- A conceptual framework is a coherent and consistent set of accounting principles which will help in standard setting.

- Some major elements in a conceptual theory are the objectives of accounting, users, user needs, information characteristics and measurement models.

- The most widely agreed objective is to provide information for decision making.

- Users include shareholders and analysts, lenders, creditors, customers and employees.

- Key information characteristics are relevance and faithful representation, which are enhanced by comparability, verifiability, timeliness and understandability.

Introduction

So far, we have looked at accounting practice – focusing on the preparation and interpretation of the financial statements of sole traders, partnerships and limited companies. In particular, we considered practical aspects of accounting such as double-entry bookkeeping, the trial balance, the income statement (profit and loss account), the statement of financial position (balance sheet), the statement of cash flows (cash flow statement) and ratio analysis. Accounting practice does not, however, take place in a vacuum. It is bounded both by a regulatory framework and a conceptual framework. These frameworks have grown up over time to bring order and fairness into accounting practice. They have been devised principally in relation to limited companies, but are also relevant to some extent to sole traders and partnerships.

The regulatory framework is essentially the set of rules and regulations which govern corporate accounting practice. At the international level, the regulatory framework is provided by the International Accounting Standards Board. This applies to all European listed companies, including UK companies. In the UK, regulations are set down mainly by government in Companies Acts and by independent private sector regulation in accounting standards. These cover small and medium-sized companies. The conceptual framework seeks to set out a theoretical and consistent set of accounting principles by which financial statements can be prepared.

Traditional Corporate Model: Directors, Auditors and Shareholders

In what I term the traditional corporate model, there are three main groups (directors, auditors and shareholders). As Figure 10.1 shows, these three groups interact. This interaction is explained in more detail below.

The directors are responsible for preparing the accounts – in practice this is usually delegated to the accounting managers. These accounts are then checked by professionally qualified accountants, the auditors. Finally, the accounts are sent to the shareholders.

1. Directors

The directors are those responsible for running the business. They are accountable to the shareholders, who in theory appoint and dismiss them. The relationship between the directors and shareholders is sometimes uneasy. The shareholders own the company, but it is the directors who run it. This relationship is often termed a ‘principal–agent’ relationship. The shareholders are the principals and the directors are the agents. The principals delegate the management of the company to directors. However, the directors are still responsible to the shareholders.

The directors are responsible for preparing the accounts which are sent to the shareholders. These accounts, prepared annually, allow the shareholders to assess the performance of the company and of the directors. They also provide information to shareholders to enable them to make share trading decisions (i.e., to hold their shares, to buy more shares or to sell their shares). As a reward for running the company, the directors receive emoluments. These may take the form of a salary, profit-related bonuses or other benefits in kind such as share options or company cars.

2. Auditors

Unfortunately, human nature being human nature, there is a problem with such arm's-length transactions. In a nutshell, how can the shareholders trust accounts prepared by the directors? For example, how can they be sure that the directors are not adopting creative accounting in order to inflate profits and thus pay themselves inflated profit-related bonuses? One way is by auditing.

The auditors are a team of professionally qualified accountants who are independent of the company. They are appointed by the shareholders on the recommendation of the directors. It is their job to check and report on the accounts. This checking and reporting involves extensive work verifying that the transactions have actually occurred, that they are recorded properly and that the monetary amounts in the accounts do indeed provide a true and fair view of the company's financial position and performance.

An audit (see Definition 10.1) is thus an independent examination and report on the accounts of a company.

The Audit

Working definition

An independent examination and report on the accounts.

Formal definition

‘The systematic independent examination of a business's, normally a company's, accounting systems, accounting records and financial statements in order to provide a report on whether or not they provide a true and fair view of the business's activities.’

CIMA definition

‘Systematic examination of the activities and status of an entity, based primarily on investigation and analysis of its systems, contracts and rewards.’

Source: Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (2005), Official Terminology. Reproduced by Permission of Elsevier.

For their time and effort the auditors are paid often quite considerable sums. The auditors prepare a formal report for shareholders. This is part of the annual report. In Company Snapshot 10.1 we attach an auditors’ report prepared by PriceWaterhouseCoopers, the auditors of Rentokil, on Rentokil's 2009 accounts.

Report of the Auditors

Independent auditors’ report to the members of Rentokil Initial plc

We have audited the financial statements of Rentokil Initial plc for the year ended 31 December 2009 set out on pages 39 to 84 and 87 to 93. The financial reporting framework that has been applied in the preparation of the group financial statements is applicable law and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs) as adopted by the EU. The financial reporting framework that has been applied in the preparation of the parent company financial statements is applicable law and UK Accounting Standards (UK Generally Accepted Accounting Practice).

This report is made solely to the company's members, as a body, in accordance with sections 495, 496 and 497 of the Companies Act 2006. Our audit work has been undertaken so that we might state to the company's members those matters we are required to state to them in an auditors’ report and for no other purpose. To the fullest extent permitted by law, we do not accept or assume responsibility to anyone other than the company and the company's members, as a body, for our audit work, for this report, or for the opinions we have formed.

Respective responsibilities of directors and auditors

As explained more fully in the Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities set out on page 24, the directors are responsible for the preparation of the financial statements and for being satisfied that they give a true and fair view. Our responsibility is to audit the financial statements in accordance with applicable law and International Standards on Auditing (UK and Ireland). Those standards require us to comply with the Auditing Practices Board's (APB's) Ethical Standards for Auditors.

Scope of the audit of the financial statements

A description of the scope of an audit of financial statements is provided on the APB's website at http://www.frc.org.uk/apb/scope/UKP.

Opinion on financial statements

In our opinion:

- the financial statements give a true and fair view of the state of the group's and of the parent company's affairs as at 31 December 2009 and of the group's profit for the year then ended;

- the group financial statements have been properly prepared in accordance with IFRSs as adopted by the EU;

- the parent company financial statements have been properly prepared in accordance with UK Generally Accepted Accounting Practice;

- the financial statements have been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Companies Act 2006; and, as regards the group financial statements, Article 4 of the IAS Regulation.

Opinion on other matters prescribed by the Companies Act 2006

In our opinion:

- the part of the Directors’ Remuneration Report to be audited has been properly prepared in accordance with the Companies Act 2006; and

- the information given in the Directors’ Report for the financial year for which the financial statements are prepared is consistent with the financial statements.

Matters on which we are required to report by exception

We have nothing to report in respect of the following:

Under the Companies Act 2006 we are required to report to you if, in our opinion:

- adequate accounting records have not been kept by the parent company, or returns adequate for our audit have not been received from branches not visited by us; or

- the parent company financial statements and the part of the Directors’ Remuneration Report to be audited are not in agreement with the accounting records and returns; or

- certain disclosures of directors’ remuneration specified by law are not made; or

- we have not received all the information and explanations we require for our audit.

Under the Listing Rules we are required to review:

- the directors’ statement, set out on page 30, in relation to going concern; and

- the part of the Corporate Governance Statement relating to the company's compliance with the nine provisions of the June 2008 Combined Code specified for our review.

Simon Figgis (Senior Statutory Auditor)

For and on behalf of KPMG Audit Plc, Statutory Auditor

Chartered Accountants

8 Salisbury Square

London

EC4Y 8BB

26 March 2010

Source: Rentokil Initial plc Annual Report 2009, p. 94.

This auditors’ report thus confirms that the directors of Rentokil have prepared a set of financial statements which have given a true and fair view of the company's accounts as at 31 December 2009. This is known as a clean audit report. In this case, therefore, the auditors have not drawn the shareholders’ attention to any discrepancies. A qualified auditors’ report, by contrast, would be an adverse opinion on some aspect of the accounts, for example, compliance with a particular accounting standard. Shareholders of Rentokil can thus draw comfort from the fact that the auditors believe the accounts do give a true and fair view and faithfully reflect the economic performance of the company over the year.

3. Shareholders

The shareholders (in the US known as the stockholders) own the company. They have provided funding to the business in exchange for shares. Their reward is twofold. First, they may receive an annual dividend which is simply a cash payment from the company based on profits. Second, they may benefit from any increase in the share price over the year. However, companies may make losses and share prices can go down as well as up, so this reward is not guaranteed. In the developed world, more and more companies are owned by large institutions (such as investment trusts or pension funds) rather than private shareholders.

The shareholders of the company receive an annual audited statement of the company's performance. This is called the annual report. It comprises the financial statements and also a narrative explanation of corporate performance. Included in this annual report is an auditors’ report.

It is important to realise that shareholders are only liable for the equity which they contribute to a company. This equity is known as share capital (i.e., the capital of a company is divided into many shares). These shares limit the liability of shareholders and so we have limited liability companies. Shares, once issued, are bought or sold by shareholders on the stock market. This enables people who are not involved in the day-to-day running of the business to own shares. This division between owners and managers is often known as the divorce of ownership and control. It is a fundamental underpinning of a capitalist society.

Risk and Reward

In the corporate model each of the three groups is rewarded for its contributions. This is called the ‘risk and reward model’. Can you work out each group's risk and reward?

| Contribution (risk) | Reward | |

| Shareholders | Share capital | Dividends and increase in share price |

| Directors | Time and effort | Salaries, bonuses, benefits-in-kind such as cars or share options |

| Auditors | Time and effort | Auditors’ fees |

Regulatory Framework

The corporate model of directors, shareholders and auditors is one of checks and balances. The directors manage the company, receive directors’ emoluments and recommend the appointment of the auditors to the shareholders. The shareholders own the company, but do not run it, and rely upon the auditors to check the accounts. Finally, the auditors are appointed by shareholders on the recommendation of the directors. They receive an auditors’ fee for the work they undertake when they check the financial statements prepared by managers.

Checks and Balances

Is auditing enough to stop company directors pursuing their own interests at the expense of the shareholders?

Auditing is a powerful check on directors’ self-interest. The directors prepare the accounts and the auditors check that the directors have correctly prepared them and that they give a ‘true and fair’ view. However, there are problems. The auditors, although technically appointed by the shareholders at the company's annual general meeting (i.e., a meeting called once a year to discuss a company's accounts), are recommended by directors. Auditors are also paid, often huge fees, by the company. The auditors do not wish to upset the directors and lose those fees. Given the flexibility within accounts, there is a whole range of possible accounting policies which the directors can choose. The regulatory framework helps to narrow this range of potential accounting policies and gives guidance to both directors and auditors. The auditors can, therefore, point to the rules and regulations if they feel that the directors’ accounting policies are inappropriate. The regulatory framework is, therefore, a powerful ally of the auditor.

This system of checks and balances is fine, in principle. However, it is rather like having two football teams and a referee with no rules. The regulatory framework, in effect, provides a set of rules and regulations to ensure fair play. As Definition 10.2 shows, at the national level, these rules and regulations may originate from the government, the accounting standard setters or, more rarely, for listed companies, the stock exchange. The principal aim of the regulatory framework is to ensure that the financial statements present a true and fair view of the financial performance and position of the organisation.

The National Regulatory Framework

Working definition

The set of rules and regulations which govern accounting practice, mainly prescribed by government and the accounting standard-setting bodies.

Formal definition

‘The set of legal and professional requirements with which the financial statements of a company must comply. Company reporting is influenced by the requirements of law, of the accounting profession and of the Stock Exchange (for listed companies).’

Source: Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (2000), Official Terminology. Reproduced by Permission of Elsevier.

Regulations

‘If you destroy a free market you create a black market. If you have ten thousand regulations, you destroy all respect for the law.’

Winston S. Churchill

Source: The Book of Unusual Quotations (1959), pp. 240–41.

In most countries, including the UK, the main sources of authority for the regulatory framework are either via the government through companies legislation or via accounting standard-setting bodies through accounting standards. As Soundbite 10.1 suggests, there is a need not to overregulate. At the international level, there is now a set of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB). The IASB is steadily growing in importance. Its standards are aimed primarily at large international companies (see Chapter 14 for a fuller discussion of IFRS). However, nowadays many other entities use IFRS. European listed companies must comply with IFRS.

International Accounting Standards

Over the last decade, both in the UK and in other European (and indeed non-European) countries, the role of the International Accounting Standards Board has grown in importance. The IASB has published International Accounting Standards (IAS) or International Financial Reporting Standards which are dealt with in more depth in Chapter 14. However, it is important to set the scene here.

From 2005, IAS (issued by the International Accounting Standards Committee up to 2001) and IFRS (issued by the International Accounting Standards Board (from 2001)) have been used by UK listed companies in their group accounts. These standards are based on a conceptual framework set out by the International Accounting Standards Board (see section later in this chapter).

However, these international standards are being used by more and more organisations such as the UK's National Health System and publicly accountable organisations. Also globally IFRS are now being used widely, for example, by countries in the European Union.

Regulatory Framework in the UK

Most countries have a national regulatory framework that exists alongside IFRS. For example in the UK, there are two main sources of authority for regulation: the Companies Acts and accounting standards. There are some additional requirements from the Stock Exchange for listed companies, but given their relative unimportance, they are not discussed further here.

In the UK, as in most countries, the regulatory framework has evolved over time. As accounting has grown more complex, so has the regulatory framework which governs it. At first, the only requirements that companies followed were those of the Companies Acts. However, in 1970 the first accounting standards set by the Accounting Standards Steering Committee were issued. Today, UK companies must adhere both to the requirements of Companies Acts and to accounting standards. For non-listed companies these are set by the Accounting Council (formerly the Accounting Standards Board (ASB)), for listed companies by the International Accounting Standards Board. The UK accounting standards are increasingly becoming less influential. However, from July 2013 the smallest UK companies will continue to use a simplified version of UK standards, while medium-sized companies will use a standard based on IFRS for small and medium-sized enterprises (IFRS for SMEs). The overall aim of this regulatory framework is to protect the interests of all those involved in the corporate model. Specifically, there is a need to provide a ‘true and fair view’ of a company's affairs.

True and Fair View

Section 404 of the 2006 Companies Act requires that for companies following the Companies Acts Group Accounts (rather than IFRS Group Accounts): ‘the accounts must give a true and fair view of the state of affairs as at the end of the financial year, and the profit or loss for the financial year, of the undertakings included in the consolidation as a whole, so far as concerns members of the company’. The ‘true and fair’ concept is thus of overriding importance. Unfortunately, it is a particularly nebulous concept which has no easy definition. A working definition is, however, suggested in Definition 10.3 below. In essence, there is a presumption that the accounts will reflect the underpinning economic reality. Generations of accountants have struggled unsuccessfully to pin down the exact meaning of the phrase. In general, to achieve a true and fair view accounts should comply with the Companies Acts and accounting standards.

Occasionally, however, where compliance with the law would not give a true and fair view, a company may override the legal requirements. However, the company would have to demonstrate clearly why this was necessary.

Working Definition of a ‘True and Fair View’

A set of financial statements which faithfully, accurately and truly reflect the underlying economic transactions of an organisation.

Companies Acts

Companies Acts are Acts of Parliament which lay down the legal requirements for companies including regulations for accounting. There has been a succession of Companies Acts which have gradually increased the reporting requirements placed on UK companies. Initially, the Companies Acts provided only a broad legislative framework. However, later Companies Acts (CAs), especially the CA 1981, have imposed a significant regulatory burden on UK companies. The CA 1981 introduced the European Fourth Directive into UK law. Effectively, this Directive was the result of a deal between the United Kingdom and other European Union members. The United Kingdom exported the true and fair view concept, but imported substantial detailed legislation and standardised formats for the income statement (profit and loss account) and statements of financial position (balance sheets). The CA 1981, therefore, introduced a much more prescriptive ‘European’ accounting regulatory framework into the UK. The latest Companies Act is the CA 2006 which has introduced IFRS into British law. Group Accounts may be prepared in accordance with Section 404 (Companies Act Group Accounts) or in accordance with international accounting standards (IFRS Group Accounts).

Accounting Standards

Whereas Companies Acts are governmental in origin, accounting standards are set by nongovernmental bodies. Accounting standards were introduced, as Real-World View 10.1 indicates, to improve the quality of UK financial reporting.

Introduction of Accounting Standards

Inflation accounting was, in fact, only one part of a bigger move towards accounting standards – a move that was itself controversial. Standards had been proposed a few years earlier to limit the scope for judgement in the preparation of accounts. They were the profession's response to a huge City row when GEC chief executive Arnold Weinstock restated the profits of AEI, a company he had just taken over, from mega millions down to zero.

The City was outraged and demanded more certainty in accounts so it could have more faith in public profit figures.

Standards were the result and, though taken for granted now, many saw them as the death knell for the profession, precisely because they limited the scope for professional judgement. Many believed the profession had been permanently diminished when its ability to make judgements was curtailed.

Source: Anthony Hilton, Demands for Change, Accountancy Age, 11 November 2004, p. 25.

At the international level, International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) are set by the International Accounting Standards Board. These are now mandatory for all European listed companies in their group accounts. The US market does not accept IFRS at present without reconciliation to US GAAP. However, there are ongoing discussions between the IASB and the US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) about convergence. UK nonlisted companies may still follow UK accounting standards. The role of the IASB is discussed in more detail in Chapter 14.

The UK's accounting setting regime has evolved over time. The current regulatory framework was set up in 1990, reorganised in 2004 and then again in July 2012. In 2004, the structure consisted of a Financial Reporting Council which supervised five boards regulating accounting, accountants and auditing: the Auditing Practices Board, Accounting Standards Board, Financial Reporting and Review Panel, Investigation and Discipline board and Professional Oversight Board. The new FRC structure set up in July 2012 is shown in Figure 10.2. The main elements that concern accounting are the Codes and Standards Committee, the Accounting Council, the Financial Reporting Review Panel and the Audit and Assurance Council.

There was much concern in the accounting community about the abolition of the Accounting Standards Board. Effectively, it has been replaced by the Accounting Council.

1. Financial Reporting Council (FRC).

The Financial Reporting Council is a supervisory body which ensures that the overall system is working. As can be seen in Figure 10.2, the FRC supervises a Codes and Standards Committee, an Executive Committee and a Conduct Committee. The main accounting functions come under the Codes and Standards Committee in terms of the Accounting Council and Audit and Assurance Council. In addition, the Financial Reporting Review Panel comes under the Monitoring Committee. These are discussed more fully below.

2. Codes and Standards Committee.

This was established in 2012. It is responsible for advising the FRC board on monitoring an effective framework of UK codes and standards for corporate governance, stewardship, accounting, auditing and assurance and actuarial technical standards. This board is advised by the Accounting Council (including accounting and accounting narratives), the Audit and Assurance Council, and the Actuarial Council.

3. Accounting Council.

The Accounting Council took over from the ASB in 2012. It is the engine of the accounting standards process. In the UK, accounting standards are called Financial Reporting Standards (FRS). The Accounting Council issues FRS which are applicable to the accounts of all UK companies not following IFRS and are intended to give a true and fair view. These Financial Reporting Standards have replaced most of the Standard Statements of Accounting Practice which were issues from 1970 to 1990 by the Accounting Council's and the ASB's predecessor, the Accounting Standards Committee. Listed companies follow IFRS issued by the International Accounting Standards Board. It is planned to extend IFRS to all publicly accountable UK entities. The Accounting Council collaborates with accounting standard setters from other countries and particularly with the International Accounting Standards Board. As Definition 10.4 shows, in essence, accounting standards are pronouncements which must normally be followed in order to give a true and fair view. The Accounting Counicl has taken over the role of the Urgent Issues Task Force (UITF). As accounting standards take time to develop, the Accounting Council needs to react quickly to new situations. Recommendations are made to curb undesirable interpretations of accounting standards or to prevent accounting practices which the Accounting Council considers undesirable.

Accounting Standards

Working definition

Accounting pronouncements which must be followed in order to give a true and fair view within the regulations.

Formal definition

‘Accounting standards are authoritative statements of how particular types of transaction and other events should be reflected in financial statements and accordingly compliance with accounting standards will normally be necessary for financial statements to give a true and fair view.’

Source: Foreword to Accounting Standards, Accounting Standards Board (1993), para. 16.

4. Audit and Assurance Council

This body created in 2012 advises the FRC board and the Codes and Standards Committee on audit and assurance matters.

Accounting standards are mandatory in that accountants are expected to observe them. They cover specific technical accounting issues such as inventory, depreciation, and research and development. These standards essentially aim to improve the quality of accounting in the UK. They narrow the areas of difference and variety in accounting practice, set out minimum disclosure standards and disclose the accounting principles upon which the accounts are based. Overall, accounting standards provide a comprehensive set of guidelines which preparers and auditors can use when drawing up and verifying the financial statements.

5. The Financial Reporting Review Panel (FRRP)

The FRRP investigates contentious departures from accounting standards. It reports to the Monitoring Committee. It is the ‘detective’ arm of the regulatory framework. The FRRP questions the directors of the companies investigated. The last resort of the FRRP is to take miscreant companies to court to force them to revise their accounts. However, so far the threat of court action has been enough. The FRRP began as a reactive body only responding to complaints. However, recently the FRRP has become more proactive as Real-World View 10.2 explains.

FRRP

When it was set up in 1990 to deal with the scandals of the eighties, the government had decided that self-regulation was the best option. It is a strategy that Sir Bryan describes as highly successful ‘because the people in the system knew they had to make it work because of the alternative’.

But since Enron, Parmalat et al, the pressure's on to up the ante. Enhancements include a new proactive approach to uncovering accounting cock-ups in the books of listed UK companies, with 300 sets of accounts slated for investigation by the Financial Reporting Review Panel (FRRP) this year.

Source: Insider, Accountancy Age, 1 April 2004, p. 15.

In 2005, for example, the FRRP investigated the accounts of MG Rover. This company was run by four businessmen and then subsequently collapsed. There were suspicions of accounting impropriety and, therefore, the FRRP looked into its finances. As Real-World View 10.3 shows this triggered a government enquiry.

FRRP and MG Rover

The Phoenix Four, the Midlands businessmen behind the collapsed MG Rover Group, are to be investigated by the Department of Trade and Industry, which has set up an independent inquiry into the affairs of the former car maker.

The inquiry was announced yesterday by Alan Johnson, the Trade and Industry Secretary. He ordered the inquiry after receiving an initial report into the company's finances by the Financial Reporting and Review Panel (FRRP), part of the accountancy watchdog, the Financial Reporting Council.

A clean bill of health for MG Rover, and its associated companies, would have left the Government little choice but to close the case. But Mr Johnson said the FRRP report ‘raises a number of questions that need to be answered’. He said the public interest demanded a more detailed account of what went on at MG Rover Group, which collapsed into administration in April with the loss of more than 5000 jobs.

Source: Damian Reece, DTI Opens MG Rover Investigation, Financial Times, 1 June 2005, p. 57.

Corporate Governance

From the 1990s, corporate governance has grown in importance. Effectively, corporate governance is the system by which companies are directed and controlled (see Real-World View 10.4).

Corporate Governance

Corporate governance is the system by which companies are directed and controlled. Boards of directors are responsible for the governance of their companies. The shareholders’ role in governance is to appoint the directors and the auditors and to satisfy themselves that an appropriate governance structure is in place. The responsibilities of the board include setting the company's strategic aims, providing the leadership to put them into effect, supervising the management of the business and reporting to shareholders on their stewardship. The board's actions are subject to laws, regulations and the shareholders in general meeting.

Within that overall framework, the specifically financial aspects of corporate governance (the committee's remit) are the way in which boards set financial policy and oversee its implementation, including the use of financial controls, and the process whereby they report on the activities and progress of the company to the shareholders.

Source: Report of the Committee on the Financial Assets of Corporate Governance (1992), Gee and Co., p. 15.

The financial aspects of corporate governance relate principally to internal controls, the way in which the board of directors functions and the process by which the directors report to the shareholders on the activities and progress of the company. These aspects have been investigated in the UK by several committees including the Cadbury Committee (1992), the Greenbury Committee (1995), the Hampel Committee (1998) and the Turnbull Committee (1999). In addition, since 2003 the Higgs, Smith, Turner, and Walker Reports as well as the Stewardship Code into corporate governance have been published.

Corporate Governance

‘Sarbanes-Oxley was brought in to ward off any future Enrons by, effectively, creating a vast network of internal controls and regulations that would, the legislators intended, make Enronscale corporate deceptions impossible.’

Source: Robert Bruce, Winds of Change, Accountancy Magazine, February 2010, p. 27.

The continuing interest in corporate governance arises in part for two reasons. First, there have been some unexpected failures of major companies such as Polly Peck, Maxwell Communications, WorldCom, Enron and Parmalat. In the US, in particular, this has led to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (see Soundbite 10.2). The Sarbanes-Oxley Act was the US government's response to Enron and WorldCom. Since 2004, all US companies have submitted details of their internal control systems to the US Security Exchange Council (SEC). These control systems are also audited. Second, there have been extensive criticisms in the press of ‘fat-cat’ directors. These directors, often of privatised companies (i.e., companies which were previously state-owned and run), are generally perceived to be paying themselves huge and unwarranted salaries.

As a result of the Cadbury Committee and other subsequent committees, there were attempts to tighten up corporate governance in the UK. In particular, there was a concern with the amount of information companies disclosed, with the role of non-executive directors (i.e., directors appointed from outside the company), with directors’ remuneration, with audit committees (committees ideally controlled by non-executive directors which oversee the appointment of external auditors and deal with their reports), with relations with institutional investors and with systems of internal financial control set up by management.

Companies are very concerned to demonstrate their good corporate governance structure. In the UK, the Financial Reporting Council in 2010 revised the UK's Corporate Governance Code. Marks and Spencer plc, for example, has aligned its governance with the themes in this Code: leadership's effectiveness, accountability, communication and remuneration. Marks and Spencer has outlined its governance structure in its 2010 annual report (see Company Snapshot 10.2).

Governance Structures: Marks and Spencer

Source: Marks and Spencer plc, Annual Report and Financial Statements 2010.

In the annual report, companies now set out extensive details of directors’ remuneration and disclose information about corporate governance. The auditors review these corporate governance elements to check that they comply with the principles of good governance and code of best practice as set out in the London Stock Exchange's rules. Company Snapshot 10.3 presents part of J.D. Wetherspoon's corporate governance statement which relates to internal control. The directors acknowledge their responsibility to establish controls such as those to protect against the unauthorised use of assets.

Internationally, there are two main approaches to corporate governance: rules-based and principles-based. The US adopts a rules-based approach as set out in the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. By contrast, the UK takes a more principles-based approach. Companies in the UK comply with the regulations or explain why they are not complying (usually termed a comply or explain approach).

Corporate Governance

Nomination committee

A formal nomination committee has been established, comprising John Herring (chairman), Debra van Gene, Elizabeth McMeikan and Sir Richard Beckett. The nomination committee meets as appropriate and considers all possible board appointments and also the re-election of directors, both executive and non-executive. No director is involved in any decision about his or her own re-appointment. Under the terms of the Code, one of the members of the committee was not independent.

The terms of reference of the nomination committee are available on request.

Company secretary

All directors have access to the advice of the company secretary, responsible to the board for ensuring that procedures are followed. The appointment and removal of the company secretary is reserved for consideration by the board as a whole. Procedures are in place for seeking independent professional advice, at the Company's expense.

Relations with shareholders

The board takes considerable measures to ensure that all board members are kept aware of both the views of major shareholders and changes in the major shareholdings of the Company. Efforts made to accomplish effective communication include:

- Annual general meeting, considered to be an important forum for shareholders to raise questions with the board

- Regular feedback from the Company's stockbrokers

- Interim, full and ongoing announcements circulated to shareholders

- Any significant changes in shareholder movement being notified to the board by the company secretary, when necessary

- The company secretary maintaining procedures and agreements for all announcements to the City

- A programme of regular meetings between investors and directors of the Company, including the senior independent director, as appropriate

- The capital structure of the company is described in note 24 to the accounts.

Risk management

The board is responsible for the Company's risk-management process.

The internal audit department, in conjunction with the management of the business functions, produces a risk register annually. This register has been compiled by the business using a series of facilitated control and risk self-assessment workshops, run in conjunction with internal audit. These workshops were run with senior management from the key business functions.

The identified risks are assessed based on the likelihood of a risk occurring and the potential impact to the business, should the risk occur. The head of internal audit determines and reviews the risk assessment process and will communicate the timetable annually.

The risk register is presented to the audit committee every six months, with a schedule of audit work agreed on, on a rolling basis. The purpose of this work is to review, on behalf of the Company and board, those key risks and the systems of control necessary to manage such risks.

The results of this work are reported back to relevant senior management and the audit committee. Where recommendations are made for changes in systems or processes to reduce risk, internal audit will follow up regularly to ensure that the recommendations are implemented.

Internal control

During the year, the Company and the board continued to support and invest in resource to provide an internal audit and risk-management function. The system of internal control and risk mitigation is deeply embedded in the operations and the Company culture. The board is responsible for maintaining a sound system of internal control and reviewing its effectiveness. The function can only manage, rather than entirely eliminate, the risk of failure to achieve business objectives. It can provide only reasonable and not absolute assurance against material misstatement or loss. Ongoing reviews, assessments and management of significant risks took place throughout the year under review and up to the date of the approval of the annual report and accords with the Turnbull Guidance (Guidance on Internal Control).

The Company has an internal audit function which is discharged as follows:

- Regular audits of the Company stock

- Unannounced visits to retail units

- Monitoring systems which control the Company cash

- Health & safety visits, ensuring compliance with Company procedures

- Reviewing and assessing the impact of legislative and regulatory change

- Annually reviewing the Company's strategy, including a review of risks facing the business

- Risk-management process, identifying key risks facing the business (Company Risk Register).

The Company has key controls, as follows:

- Clearly defined authority limits and controls over cash-handling, purchasing commitments and capital expenditure

- Comprehensive budgeting process, with a detailed 12-month operating plan and a midterm financial plan, both approved by the board

- Business results are reported weekly (for key times), with a monthly comprehensive report in full and compared with budget

- Forecasts are prepared regularly throughout the year, for review by the board

- Complex treasury instruments are not used; decisions on treasury matters are reserved by the board

- Regular reviews of the amount of external insurance which it obtains, bearing in mind the availability of such cover, its costs and the likelihood of the risks involved

- Regular evaluation of processes and controls in relation to the Company's financial reporting requirements.

The directors confirm that they have reviewed the effectiveness of the system of internal control. Directors’ insurance cover is maintained.

Keith Down

Company Secretary

10 September 2010

Source: J.D. Wetherspoon plc, Annual Report and Accounts 2010, p. 68.

Conceptual Framework

Conceptual Framework

The development of a coherent and consistent set of accounting principles which underpin the preparation and presentation of financial statements.

Since the 1960s, standard-setting bodies (such as the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), in the USA, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) and the Accounting Standards Board (1990–2012) in the UK) have sought to develop a conceptual framework or statement of principles which will underpin accounting practice. As Definition 10.5 shows, the basic idea of a conceptual framework is to create a set of fundamental accounting principles which will help in standard setting.

A major achievement of the search for a conceptual theory has been the emergence of the decision-making model. As Real-World View 10.5 sets out, there is a need to provide decision-useful information to investors. In accounting, a conceptual framework has developed over time. In 1989, the IASC published a Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements. The aim of the conceptual framework is to assist the IASB in developing standards, help other standard setters and assist preparers, auditors and users in interpreting and understanding financial statements. The six essential components of a conceptual framework are broadly agreed by all three major standard-setting bodies: objectives, users, user needs, elements of financial statements, information characteristics and measurement principles with concepts of capital maintenance. These components are briefly discussed below. The various elements of the financial statements such as financial position (assets, liabilities, and equity) and performance (income and expenses), have been discussed already in Section A. The IASB updated its conceptual framework and its latest version was published in 2010.

Conceptual Framework

First – and of fundamental importance – all involved in global financial reporting must have a common mission or objective. At the heart of that mission is a conceptual framework which must focus on the investor, provide decision-useful information, and assure that capital is allocated in a manner that achieves the lowest cost in our world markets. I believe we all have an understanding and acceptance of providing decision-useful information for investors, but not all standard setters and not all standards yet reflect that mission.

Source: International Accounting Standards Board, IASC Insight, p. 12. Copyright © 2012 IFRS Foundation. All rights reserved. No permission granted to reproduce or distribute.

1. Objectives

The IASB has determined that ‘[t]he objective of general purpose financial reporting is to provide financial information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors in making decisions about providing resources to the entity. Those decisions involve buying, selling or holding equity and debt instruments, and providing or settling loans and other forms of credit’ (Conceptual Framework, IASB, 2010, OB2). This replaces the previous objective that had been agreed by the US Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB): ‘The objective of financial statements is to provide information about the financial position, performance and changes in financial position of an entity that is useful to a wide range of users in making economic decisions’ (Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements, IASB, 1999, para. 12). It will be seen that the 2010 definition is more investor-focused than that in 1999. This approach to accounting is widely known as the decision-making model (see Figure 10.3). In other words, the basic idea of accounting is to provide accounting information to users which fulfils their needs, thus enabling them to make decisions. Encompassed within this broad definition is the idea that financial statements show how the managers have accounted for the resources entrusted to them by the shareholders. This accountability is often called stewardship. To enable stewardship and decision making, the information must have certain information characteristics and use a consistent measurement model.

In the UK, the ASB (1990–2012) had developed a Statement of Principles. The Statement takes a broader definition of the objectives of financial reporting than either the FASB or the IASB. ‘The objective of financial statements is to provide information about the reporting entity's financial position, performance and changes in financial position that is useful to a wide range of users for assessing the stewardship of the entity's management and for making economic decisions’ (Accounting Standards Board, Statement of Principles, 1999). Thus, the ASB (now the Accounting Council) sees the objective of financial reporting as (i) the stewardship of management and (ii) making economic decisions.

Stewardship and decision making are discussed in more depth in Chapter 12. However, at this stage it is important to introduce them. Stewardship is all about accountability. It seeks to make the directors accountable to the shareholders for their stewardship or management of the company. Corporate governance is one modern aspect of stewardship. Decision making, by contrast, focuses on the need for shareholders to make economic decisions, such as to buy or sell their shares. As performance measurement and decision making have grown in importance so has the income statement. In a sense, decision making and stewardship are linked, as information is provided to shareholders so that they can make decisions about the directors’ stewardship of the company. There has been much debate as to whether stewardship or decision making should be given primacy when drawing up financial statements.

Essentially, stewardship and decision making are user-driven and take the view that accounting should give a ‘true and fair’ view of a company's accounts. By contrast, the public relations view suggests that there are behavioural reasons why managers might seek to prepare accounts that favour their own self-interest. Self-interest and ‘true and fair’ may well conflict. In this section, we focus only on the officially recognised roles of accounting (stewardship and decision making). Discussion of the public relations role and the conflicting multiple accounting objectives is covered in Chapter 12.

Stewardship and Decision Making

Why are assets and liabilities most important for stewardship, but profits most important for decision making?

Stewardship is about making individuals accountable for assets and liabilities. In particular, stewardship focuses on the physical existence of assets and seeks to prevent their loss and/or fraud. Stewardship is, therefore, about keeping track of assets rather than evaluating how efficiently they are used.

Decision making is primarily concerned with monitoring performance. Therefore, it is primarily concerned with whether or not a business has made a profit. It is less concerned with tracking assets.

2. Users

The main users are usually considered to be the present and future shareholders. Indeed, shareholders are the only group required by law to be sent an annual report. Shareholders comprise individual and institutional shareholders. Besides shareholders, there are a number of other users. In its most recent version of the Conceptual Framework (2010), the IASB focuses on existing and potential investors, lenders and other creditors. However, before this the IASB identified a wider set of users including:

- lenders, such as banks or loan creditors

- suppliers and other trade creditors (i.e. trade payables)

- employees and employee organisations

- customers

- governments and their agencies, and the

- general public

- analysts and advisers.

In addition to this list we can add:

- academics

- management

- pressure groups such as Friends of the Earth.

Broadly, we can see that this list is broadly the same as that discussed in Chapter 1 (see Figure 1.3). In Chapter 1, however, we distinguished between internal users (management and employees) and external users (the rest). All of these users will need the information to appraise the performance of management and also to make decisions.

Generally the accounts are pitched at the shareholders. Their primary requirement is to acquire economic information so that they can make economic decisions. Satisfying the interests of shareholders is generally thought to cover the main concerns of the other groups. The annual report adopts a general purpose reporting model. This provides a comprehensive set of information targeted at all users. It does not, therefore, specifically target the needs of one user group.

3. User Needs

User needs vary. However, commonly users will want answers to questions such as:

- How well is management running the company?

- How profitable is the organisation?

- How much cash does it have in the bank?

- Is it likely to keep trading?

The IASB looks at the needs of external users and believes that user needs will be focused on economic decisions such as to:

- Decide to buy, hold or sell shares

- Assess the stewardship or accountability of management

- Assess the ability of the entity to pay the wages

- Assess the security for monies lent

- Determine tax policy

- Determine distributable profits and dividends

- Prepare and use national income statistics

- Regulate an entity's activities.

In order to answer these questions, users will need information on the profitability, liquidity, efficiency and gearing of the company. This is normally provided in the three key financial statements: the income statement, the statement of financial position and the statement of cash flows. Users will also be interested in the softer, qualitative information provided, for example, in accounting narratives such as the chairman's statement.

4. Qualitative Information Characteristics

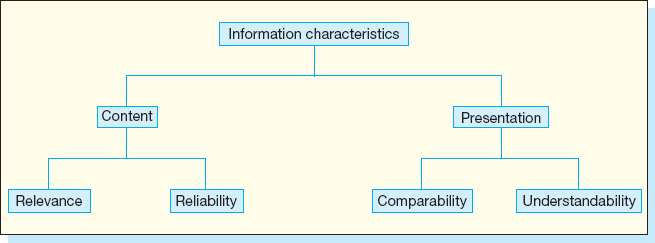

In order to be useful to users, the financial information needs to possess certain characteristics. The UK's Accounting Standards Board, now replaced by the Accounting Council, focuses on four principal characteristics: relevance, reliability, comparability and understandability. The ASB then classified these characteristics into those relating to content (relevance and reliability) and those relating to presentation (comparability and understandability) (see Figure 10.4).

This approach was also adopted by the IASB, but it has now refined its position. The IASB now sees two fundamental qualitative characteristics: relevance and faithful representation. There are then a further four characteristics that enhance relevance and faithful representation: comparability, verifiability, timeliness and understandability (Figure 10.5).

The major change in the latest conceptual framework is the replacement of reliability by representational faithfulness. The IASB abandoned ‘reliability’ because it believed there was a lack of common understanding of the term.

A. Fundamental Qualitative Characteristics

Relevance Relevant information is that which affects users’ economic decisions. Relevance is a prerequisite of usefulness. Examples of relevance are information that helps to predict future events or to confirm or correct past events. The relevance of financial information in the financial statements crucially depends on its materiality. If information is immaterial (i.e., will not affect users’ decisions), then, in practice, it does not need to be reported. Materiality is thus best considered as a threshold or cut-off point rather than being a primary qualitative information characteristic in its own right.

Faithful Representation. Financial reports represent economic phenomena in numbers and words. Like relevance, faithful representation is a prerequisite of usefulness. Three characteristics underpin information that is representationally faithful (i.e., information that validly describes the underlying events). First, information must be complete in that all necessary information should be included. Second, reliable information must be neutral, i.e., not biased. Third, faithful representation dictates that there are no errors or omissions in the information. The IASB did not see substance over form as a separate component of faithful representation. This was because a legal form which did not represent economic substance automatically violated representational faithfulness.

B. Supplementary Enhancing Qualitative Characteristics

Comparability. Accounts should be prepared on a consistent basis and should disclose accounting policies. This will then allow users to make inter-company comparisons and intra-company comparisons over time.

Verifiability. This means that different knowledgeable and independent observers could reach consensus, although not necessarily complete agreement. However, the key is that they could arrive at similar decisions.

Timeliness. This means that information should be available to decision makers in time to influence their decisions. However, some information will have a long time span, for instance, when used to assess trends over time.

Understandability. Information that is not understandable is useless. Therefore, information must be presented in a readily understandable way. In practice, this means conveying complex information as simply as possible rather than ‘dumbing down’ information. Whether financial information is understandable will depend on the way in which it is characterised, aggregated, classified and presented.

The IASB and ASB (Accounting Council) recognise that trade-offs are inevitable where conflicts arise between information characteristics. For example, out-of-date information may be useless. Therefore, some detail (e.g., faithful representation) may be sacrificed to speed of reporting (e.g., timeliness). In addition, the benefits derived from information should exceed the costs of providing it. Cost is described by the IASB as a pervasive constraint.

Prudence

Another concept which was, at one time, thought to underpin reliability is prudence. Prudent information is where assets or income are not deliberately overstated or expenses and liabilities deliberately understated. There is currently much discussion about prudence. On the one hand some believe that prudence is a sensible counter-balance against the potential over-optimism of managers. Others, by contrast, argue that a prudent view mitigates against an objective view of a business. However, the IASB has omitted prudence from its latest version of the conceptual framework. It considers that prudence would be inconsistent as it would introduce bias. However, it did state that it has sometimes been considered desirable to counteract excessively optimistic management estimates.

The Debate about Prudence

Prudence is a much debated concept. There are two main views. Many commentators believe that prudence is very useful as it balances the managerial tendency to provide over-optimistic accounts. It is, therefore, a valuable safeguard for credit and shareholders. This is certainly the view of the UK's House of Lords Committee which investigated banks and bank auditing in 2011. By contrast, others, including the IASB, think that accounts should be neutral and without bias. Therefore, as prudence introduces a negative bias into the accounts it should not underpin accounts. The House of Lords Report criticised IFRS as an ‘inferior system’ which inhibited the auditors’ ability to exercise judgement.

Both sides feel strongly!! Which view do you support?

5. Measurement Model

The objectives, users, user needs and information characteristics have proved relatively easy to agree upon. However, the choice of an appropriate measurement model for profit measurement and asset determination has caused much controversy. The measurement basis that underpins financial statements remains a modified form of historical cost. In other words, income, expenses, assets and liabilities are recorded at the date of their original monetary transaction. Unfortunately, although historical cost is relatively well understood and easy to understand, it understates assets and overstates profits, especially in times of inflation. Most commentators agree that historical cost, therefore, is flawed. However, there is no consensus on a suitable replacement. The alternative measurement models are more fully discussed in Chapter 11.

Critics of the Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework has been criticised for not achieving very much and being a social document rather than a theory document. What do you think these criticisms mean and are they fair?

The conceptual framework has brought into being the decision-making model. However, there is little agreement on the appropriate measurement model for accounting. In other words, should we continue to use historical cost or should we move towards some alternative measurement model that perhaps accounts for the effects of inflation? Critics have seen this failure to agree on a measurement model as a severe blow to the authority of the conceptual framework. In addition, there is concern that the conceptual framework has not really developed a theoretically coherent and consistent set of accounting principles at all. These critics argue that the conceptual framework is primarily descriptive – just describing what already exists. A descriptive framework is not a theoretical framework. Finally, some critics argue that the real reason for the search for a conceptual framework is to legitimise and support the notion of a standard-setting regime independent of government. The conceptual framework should thus be seen as a social document which supports the existence of an independent accounting profession.

Conclusion

In order to appreciate accounting practice properly, we need to understand the regulatory and conceptual frameworks within which it operates. These frameworks were primarily devised for published financial statements, such as those in the corporate annual report. The regulatory framework is the set of rules and regulations which governs corporate accounting practice. The International Accounting Standards Board sets International Financial Reporting Standards. These are followed by all European listed companies, including UK companies. The two major strands of the UK's regulatory framework are the Companies Acts and accounting standards. The UK's accounting standards regulatory framework consists of five elements: the Financial Reporting Council, the Codes and Standards Committee, the Accounting Council, the Audit and Assurance Council and the Financial Reporting Review Panel. Corporate governance is the system by which companies are governed.

A conceptual framework is an attempt to create a set of fundamental accounting principles which will help standard setting. A major achievement of the search for a conceptual framework has been the emergence of the decision-making model. The essence of this is that the objective of financial statements is to provide financial information useful to a wide range of users for making economic decisions. A second objective is to provide financial information for assessing the stewardship of managers. In order to be useful, the IASB believes this information must have relevance and faithful representation enhanced by comparability, verifiability, timeliness and understandability. Although there is general agreement on the essentials of a decision-making model, there is little consensus on which measurement model should underpin the decision-making process.

Selected Reading

The references below will give you further background. They are roughly divided into those on the regulatory framework and those on the conceptual framework.

Regulatory Framework

Bartlett, S.A. and M.J. Jones (1997) Annual Reporting Disclosures 1970–90: An Exemplification, Accounting, Business and Financial History, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 61–80.

This article looks at how the accounts of one firm, H.P. Bulmers (Holdings) plc, the cider makers, were affected by changes in the regulations from 1970 to 1990.

International GAAP 2012: Generally Accepted Accounting Practice under International Financial Reporting Standards, Ernst and Young 2012. A very thorough and complete look at IFRS.

Solomon, J.F. (2007) Corporate Governance and Accountability, John Wiley and Sons Ltd, Chichester.

Provides an overview of corporate governance.

The Combined Code (1998) London Stock Exchange, June.

This provides a comprehensive set of recommendations arising from the various corporate governance reports (i.e., Cadbury, Greenbury, Hampel). UK-listed companies now follow these.

The Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance (The Cadbury Committee Report) (1992), Gee and Co.

The first, and arguably the most influential, report into corporate governance. Authoritative.

UK and International GAAP (2004), Ernst and Young, Butterworth.

Provides a very comprehensive guide to UK and IFRS standards as well as to the ASB's Statement of Principles. This guide is updated annually.

Conceptual Framework

Outlines of Potential Conceptual Frameworks by Professional Bodies

Accounting Standards Board (1999) Statement of Principles, Accountancy.

This synopsis offers a good, quick insight into current thinking in the UK about a conceptual theory. The Accounting Council has taken over responsibility for this.

Accounting Standards Setting Committee (ASSC) (1975) The Corporate Report (London). A benchmark report which outlined the Committee's – at the time groundbreaking – thoughts about the theory of accounting. Easy to read.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (1978), Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1, Objectives of Financial Reporting by Business Enterprises (Stanford, FASB).

Offers an insight into the US view of a conceptual theory.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) (2000), Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements in International Accounting Standards, 2000.

The IASB's early thoughts on a conceptual theory.

International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) (2010), Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting.

A very influential document outlining the IASB's latest views.

Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions

Questions with numbers in blue have answers at the back of the book.

| Q1 | What is the role of directors, shareholders and auditors in the corporate model? |

| Q2 | What is the decision-making model? Assess its reasonableness. |

| Q3 | Discuss the view that if a regulatory framework did not exist it would have to be invented. |

| Q4 | Companies often disclose ‘voluntary’ information over and above that which they are required to do. Why do you think they do this? |

| Q5 | What is a conceptual framework and why do you think so much effort has been expended to try to find one? |

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

DEFINITION 10.1

DEFINITION 10.1 COMPANY SNAPSHOT 10.1

COMPANY SNAPSHOT 10.1 PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 10.1

PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 10.1 SOUNDBITE 10.1

SOUNDBITE 10.1 REAL-WORLD VIEW 10.1

REAL-WORLD VIEW 10.1