Chapter 9

Interpretation of accounts

‘More money has been lost reaching for yield than at the point of a gun.’

Raymond Revoe Jr, Fortune, 18 April 1994, Wiley Book of Business Quotations (1998), p. 192.

Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter you should be able to:

- Explain the nature of accounting ratios.

- Appreciate the importance of the main accounting ratios.

- Calculate the main accounting ratios and explain their significance.

- Understand the limitations of ratio analysis.

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Chapter Summary

- Ratio analysis is a method of evaluating the financial information presented in accounts.

- Ratio analysis is performed after the bookkeeping and preparation of final accounts.

- There are six main types of ratio: profitability, efficiency, liquidity, gearing, cash flow and investment.

- Three important profitability ratios are return on capital employed (ROCE), gross profit ratio and net profit ratio.

- Four important efficiency ratios are trade receivables collection period, trade payables collection period, inventory turnover ratio and asset turnover ratio.

- Two important liquidity ratios are the current ratio and the quick ratio.

- Five important investment ratios are dividend yield, dividend cover, earnings per share (EPS), price earnings ratio and interest cover.

- Ratios can be viewed collectively using Z scores or pictics.

- For some, predominately non-profit oriented businesses, it is appropriate to use non-standard ratios, such as performance indicators.

- Four limitations of ratios are that they must be used in context, the absolute size of the business must be considered, ratios must be calculated on a consistent and comparable basis and international comparisons must be made with care.

Introduction

The interpretation of accounts is the key to any in-depth understanding of an organisation's performance. Interpretation is basically when users evaluate the financial information, principally from the income statement and statement of financial position, so as to make judgements about issues such as profitability, efficiency, liquidity, gearing (i.e., amount of indebtedness), cash flow, and success of financial investment. The analysis is usually performed by using certain ‘ratios’ which take the raw accounting figures and turn them into simple indices. The aim is to try to measure and capture an organisation's performance using these ratios. This is often easier said than done!

Context

The interpretation of accounts (or ratio analysis) is carried out after the initial bookkeeping and preparation of the accounts. In other words, the transactions have been recorded in the books of account using double-entry bookkeeping and then the financial statements have been drawn up (see Figure 9.1). For this reason, the interpretation of accounts is often known as financial statement analysis. The financial statements which form the basis for ratio analysis are principally the income statement and the statement of financial position.

Overview

Two useful techniques, when interpreting a set of accounts, are (i) vertical and horizontal analysis and (ii) ratio analysis. Vertical and horizontal analysis involves comparing key figures in the financial statements. In vertical analysis, key figures (such as revenue in the income statement and total net assets in the statement of financial position) are set to 100%. Other items are then expressed as a percentage of 100. In horizontal analysis, the company's income statement and statement of financial position figures are compared across years. We return to vertical and horizontal analysis later in the chapter. For now, we focus on ratio analysis.

Broadly, ratio analysis can be divided into six major areas: profitability, efficiency, liquidity, gearing, cash flow and investment. The principal features are represented diagrammatically in Figure 9.3, but set out in more detail in Figure 9.3 on the following page. These ratios are then discussed later on in this chapter.

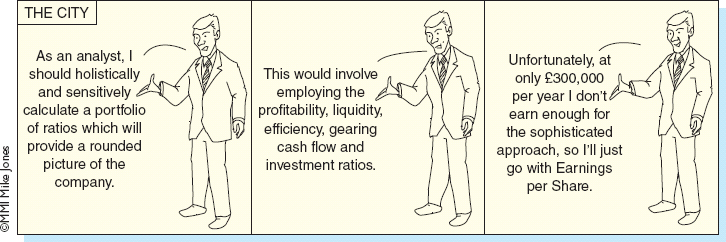

It is important to appreciate that there are potentially many different ratios. The actual ratios used will depend on the nature of the business and the individual preferences of users. The interpretation of accounts and the choice of ratios is thus inherently subjective. The ratios in Figure 9.2 have been chosen because generally they are appropriate for most businesses and are commonly used.

The 16 ratios, therefore, cover six main areas. Each of the above ratios can yield many more; for example, the gross profit ratio in Figure 9.2 is currently divided by revenue. However, gross profit per employee (divide by number of employees) or gross profit per share (divide by number of shares) are also possible. The fun and frustration of ratio analysis is that there are no fixed rules. In the UK, none of the ratios, except for earnings per share, is a regulatory requirement.

Importance of Ratios

‘Captains of industry change things. We merely comment on them. Somebody has to bring the news of the relief of Mafeking.’

Angus Phaure, August, County Natwest Business, October 1990

Source: The Book of Business Quotations (1991), p. 13.

Once the managers have prepared the accounts, then many other groups, such as investment analysts, will wish to comment on them. This is expressed in Soundbite 9.1. Different users will be interested in different ratios. For example, shareholders are primarily interested in investment ratios that measure the performance of their shares. By contrast, lenders may be interested primarily in liquidity (i.e., can the company repay its loan?). Ratios are important for three main reasons. First, they provide a quick and easily digestible snapshot of an organisation's achievements. It is much easier to glance at a set of ratios and draw conclusions from them than plough through the often quite complex financial statements. Second, ratios provide a good yardstick by which it is possible to compare one company with another (i.e., inter-firm comparisons) or to compare the same company over time (intra-firm comparisons). Third, ratio analysis takes account of size. One company may make more absolute profit than another. At first glance, it may, therefore, seem to be doing better than its competitor. However, if absolute size is taken into account it may in fact be performing less well.

Two companies, David and Goliath, have net profits of £1 million and £100 million. Is it obvious that Goliath is doing better than David?

No! We need to take into account the size of the two businesses. David may be doing worse, but then again … Imagine that David's revenue was £5 million, while Goliath's revenue was £5,000 million. Then, in £ millions,

Suddenly, Goliath's performance does not look so impressive. Size means everything when analysing ratios.

Closer Look at Main Ratios

It is now time to look in more depth at the main categories of ratio and at individual ratios. The ratios are mainly derived from the accounts of John Brown Plc. Although John Brown is a limited company, many of the ratios are also potentially usable for partnerships or sole traders. John Brown's financial statements are given at the back of this chapter as Appendix 9.1. They have been prepared for internal use and thus have more detail than in published accounts.

Some ratios (return on capital employed, trade receivables and trade payables collection period, inventory turnover and asset turnover) use average figures from two years’ accounts. In practice, two years’ figures are not always available. In this case, as for John Brown, the closing figures are used on their own. When this is done, then any conclusions must be drawn cautiously. In order to place the interpretation of key ratios in context, I have, wherever the information was available, referred to figures calculated from the UK's top publicly quoted companies. As there was no one authoritative up to date source I have used three main sources. First, information collected from Fame and Extel, two corporate databases, in July 2005. Second, where these sources were not available I used information from Fame and Extel November 2011. Third, I have used data from Jones and Finley (2011) which was based on a widespread sample of EU and Australian companies using IFRS. This article (‘Have IFRS Made a Difference to Intra-country Financial Reporting Diversity?’) was published in The British Accounting Review. The reader should be aware, however, that the way in which these sources calculate ratios may differ from the exact ratios in the book; they should thus be seen as guidelines rather than definitive figures.

Profitability Ratios

The profitability ratios seek to establish how profitably a business is operating. Profit is a key measure of business success and, therefore, these ratios are keenly watched by both internal users, such as management, and external users, such as shareholders. There are three main profitability ratios (return on capital employed, gross profit ratio and net profit ratio). The figures used are from John Brown Plc (see Appendix 9.1).

(i) Return on Capital Employed

This ratio considers how effectively a company uses its capital employed. It compares net profit to capital employed. A problem with this ratio is that different companies often use different versions of capital employed. At its narrowest, a company's capital employed is ordinary share capital and reserves. At its widest, it might equal ordinary share capital and reserves, preference shares, long-term loans (i.e., debentures) and current liabilities. Different definitions of capital employed necessitate different definitions of profits.

The most common definition measures profit before interest and tax against long-term financing (i.e., ordinary share capital and reserves, preference share capital and non-current liabilities). Therefore, for John Brown we have:

Essentially, the 17.9% indicates the return which the business earns on its capital. The key question is: could the capital be used anywhere else to gain a better return? In this example, with only one year's statement of financial position we can only take one year's capital employed. If we have an opening and a closing statement of financial position, we can take the average capital employed over the two statements of financial position. As Real-World View 9.1 shows, this is a good return on capital which has varied in recent years from 8.9% to 14.9%.

Return on Capital Ratios

The return on capital varies with the economic cycle, for example, the Investors Chronicle in October 2011 states that:

‘The latest official figures show that non-financial companies’ net return on capital in the second quarter was 12.1%. Although this is below the pre-recession peak of 14.9%, it's well above the recessionary trough of 10.6%.’

In addition, it was pointed out that this is still higher than the 1990s where, for example, in 1992 it was 8.4%.

Source: The Paradox of Corporate Profits, Chris Dillow, Investors Chronicle, 14–20 October, 2011, p.12. Financial Times

(ii) Gross Profit Ratio

The gross profit ratio (or gross profit divided by revenue) is a very useful ratio. It calculates the profit earned through trading. It is particularly useful in a business where inventory is purchased, marked up and then resold. For example, a retail business selling car batteries (see Figure 9.4) may well buy the batteries from the manufacturer and then add a fixed percentage as mark-up. In the case of pubs, it is traditional to mark up the purchase price of beer by 100% before reselling to customers.

In the case of John Brown, the gross profit is

![]()

This is the direct return that John Brown makes from buying and selling goods.

(iii) Net Profit Ratio

The net profit ratio (or net profit divided by revenue) is another key financial indicator. Whereas gross profit is calculated before taking administrative and distribution expenses into account, the net profit ratio is calculated after such expenses. Be careful with net profit as it is a tricky concept without a fixed meaning. Some people use it to mean profit before interest and tax, others to mean profit after interest but before tax, and still others profit after tax. For John Brown, some alternatives are:

The most popularly used alternative is net profit before taxation. This assumes that taxation is a factor that cannot be influenced by a business. This is the ratio which will be used from now on. As Real-World View 9.2 shows, most companies have traditionally, and still today, operate on net profit margins of less than 10%. Across the top UK 250 public limited companies this ratio was 11.4% in July 2005.

However as we have already said profits are only likely to be a comparatively minor factor in cash flow anyway. After-tax profits in even the most spectacularly successful company will rarely run at more than about 10% of annual turnover and most companies will operate at well below this figure, say, 7% or 8% before tax.

Source: B. Warnes (1984) The Genghis Khan Guide to Business, Osmosis Publications London, p. 66.

Efficiency Ratios

The efficiency ratios look at how effectively a business is operating. They are primarily concerned with the efficient use of assets. Four of the main efficiency ratios are explained below (trade receivables collection period, trade payables collection period, inventory turnover and asset turnover). The first two are related in that they seek to establish how long customers take to pay and how long it takes the business to pay its suppliers. The figures used are from John Brown (see Appendix 9.1 at the end of this chapter).

(i) Trade Receivables Collection Period (Debtors Collection Period)

This ratio seeks to measure how long customers take to pay their debts. Obviously, the quicker a business collects and banks the money, the better it is for the company. This ratio can be worked out on a monthly, weekly or daily basis. This book prefers the daily basis as it is the most accurate method. The calculation for John Brown follows:

![]()

It, therefore, takes 73 days for John Brown to collect its debts. It is important to note that ‘credit’ sales (i.e., not cash sales) are needed for this ratio to be fully effective. This information, although available internally in most organisations, may not be readily ascertainable from the published accounts. Normally, the average of opening and closing trade receivables is used to approximate average trade receivables. When this figure is not available (as in this case), we just use closing trade receivables. Across the top 250 UK plcs it took 52 days to collect money from trade receivables in July 2005.

(ii) Trade Payables Collection Period (Creditors Collection Period)

In many ways, this is the mirror image of the trade receivables collection period. It calculates how long it takes a business to pay its creditors. The slower a business is to pay the longer the business has the money in the bank! As with the trade receivables collection period, we can calculate this ratio either monthly, weekly or daily. Once more, we prefer the daily basis. This is calculated below for John Brown.

![]()

It is usually not possible to establish accurately the figure for credit purchases from the published accounts. In John Brown, cost of sales is used as the nearest equivalent to credit purchases (remember that cost of sales is opening inventory add purchases less closing inventory). However, it should be noted that if two years, accounts are available, we can deduce purchases as the following example shows for Bamber. Bamber has opening inventory £800, closing inventory £600 and cost of sales £1,400.

As with the trade receivables collection ratio, strictly we should use average trade payables for the year (i.e. normally, the average of opening and closing trade payables). If this is not available, as in this case, we use closing trade payables.

It is often important to compare the trade receivables and trade payables ratios. For John Brown, this is:

![]()

In other words John Brown collects its cash from trade receivables in 40% of the time that it takes to pay its trade payables. The management of working capital is effective. However, this is not necessarily a good thing as supplier goodwill may be lost.

Trade Receivables and Trade Payables Collection Period

Businesses whose trade receivables collection periods are much less than their trade payables collection periods are managing their working capital well. Can you think of any businesses which might be well placed to do this?

Businesses which sell direct to customers, generally for cash, would be prime examples. Pubs and supermarkets operate on a cash basis, or with short-term credit (cheques or credit cards). Their trade receivables collection period is very low. However, they may well take their time to pay their suppliers. If they have a high turnover of goods, they may collect the money for their goods from customers before they have even paid their suppliers.

(iii) Inventory Turnover Ratio (Stock Turnover Ratio)

This ratio effectively measures the speed with which inventory moves through the business. This varies from business to business and product to product. For example, crisps and chocolate have a high inventory turnover, while diamond rings have a low inventory turnover. Strictly this ratio compares cost of sales to average inventories. Where this figure is not available, we use the next best thing, closing inventory. Thus for John Brown, we have:

![]()

John Brown, therefore, holds inventory for 219 days (365 ÷ 1.66) until it is sold. This is very low.

(iv) Asset Turnover Ratio

This ratio compares revenue to total assets employed (i.e., property, plant and equipment and current assets). Businesses with a large asset infrastructure, perhaps a steel works, have lower ratios than businesses with minimal assets, such as management consultancy or dot.com businesses. Once more, where the information is available, it is best to use average total assets. For John Brown, average total assets are not available, we therefore use this year's total assets:

![]()

In other words, every year John Brown generates about half of its total assets in revenue. This is very low. There are many other potential asset turnover ratios where revenue is compared to, for example, non-current assets or net assets.

If we take these three ratios together, we can gain an insight into how efficient our cash cycle is. Thus, if we hold inventory for 219 days (inventory turnover ratio) and then debtors take 73 days to pay (trade receivables collection period). Thus, all in all it takes us 292 days to receive our money, while we pay suppliers in 183 days. Some businesses can manage to receive their cash from customers before they pay them.

Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios are derived from the statement of financial position and seek to test how easily a firm can pay its debts. Loan creditors, such as bankers, who have loaned money to a business are particularly interested in these ratios. There are two main ratios (the current ratio and quick ratio). Once more we use John Brown (Appendix 9.1).

(i) Current Ratio

This ratio tests whether the short-term assets cover the short-term liabilities. If they do not, then there will be insufficient liquid funds to pay current liabilities as they fall due. For John Brown this ratio is:

![]()

In other words, the short-term assets are double the short-term liabilities. John Brown is well covered. Across the top 250 UK plcs, this ratio was 2.16 in July 2005. In other words, current assets were double current liabilities.

(ii) Quick Ratio

This is sometimes called the ‘acid test’ ratio. It is a measure of extreme short-term liquidity. Basically, inventories are sold, turning into trade receivables. When the debtors pay, the business gains cash. The quick ratio excludes inventory, the least liquid (i.e., the least cash-like) of the current assets, to arrive at an immediate test of a company's liquidity. If the creditors come knocking on the door for their money, can the business survive? For John Brown we have:

![]()

For John Brown, the answer is yes. John Brown has just enough trade receivables and cash to cover its immediate liabilities. Across the top 250 UK plcs in July 2005 this ratio was 1.80.

Gearing

Like liquidity ratios, gearing ratios are derived from the statement of financial position. Gearing is also often known as leverage. Gearing effectively represents the relationship between the equity and the debt capital of a company. Essentially, equity represents the funding provided by owners (i.e., ordinary shareholders). By contrast, debt capital is that supplied by external parties (normally preference shareholders and loan holders).

So far, so good. However, the role of preference share capital and short-term liabilities is worth discussing. First, preference share capital is technically part of shareholders’ funds, but preference shareholders do not own the company and usually receive a fixed dividend. We therefore treat them as debt. Second, current liabilities and short-term loans, to some extent, do finance the company. However, generally gearing is concerned with long-term borrowing. Figure 9.5 now summarises shareholders’ funds and long-term borrowings:

We can now calculate the gearing ratio for John Brown. The preferred method used in this book is to compare long-term borrowings to total long-term capital employed (i.e., equity funding plus long-term borrowings). Thus we have for John Brown:

In other words, 36% (or 36 pence in every £1) of John Brown is financed by long-term non-ownership capital. Essentially, the more highly geared a company, the more risky the situation for the owners when profitability is poor. This is because interest on long-term borrowings will be paid first. Thus, if profits are poor, there may be little, if anything, left to pay the dividends of ordinary shareholders. Conversely, if profits are booming there will be relatively more profits left for the ordinary shareholders since the return to the ‘lenders’ is fixed. When judging the gearing ratio, it is thus important to bear in mind the overall profitability of the business. According to Jones and Finley (2011) this ratio was 72.67% in 2006 for their sample of EU and Australian companies.

Cash Flow

The cash flow ratio, unlike the other ratios we have considered so far, is prepared from the statement of cash flows, not the income statement or statement of financial position. There are many possible ratios, but the one shown here simply measures total cash inflows to total cash outflows. Figure 9.6 shows the situation using IFRS whereas Appendix 9.2 illustrates the situation using the UK GAAP cash flow statement.

Other commonly used cash flow ratios are cash flow cover (net operating cash flow divided by annual interest payments), total debt to cash flow and cash flow per share.

Investment Ratios

The investment ratios differ from the other ratios, as they focus specifically on returns to the shareholder (dividend yield, earnings per share and price/earnings ratio) or the ability of a company to sustain its dividend or interest payments (dividend cover and interest cover). The ratios once more are calculated from John Brown (see Appendix 9.1). The first four ratios covered below are mainly of concern to the shareholders. The fifth, interest cover, is of more interest to the holders of long-term loans. Many companies give details of investment ratios in their annual reports. Company Snapshot 9.1 shows the earnings per share, dividends per share and dividend cover for Manchester United from 2000 to 2004.

(i) Dividend Yield

This ratio shows how much dividend the ordinary shares earn as a proportion of their market price. The market price for the shares of leading public companies is shown daily in many newspapers, such as (in the UK) the Financial Times, the Guardian, the Telegraph or The Times. Dividend yield can be shown as net or gross of tax (dividends are paid net after deduction of tax; gross is inclusive of tax). The calculation of gross dividend varies according to the tax rate and tax rules. For simplicity, we just show the net dividend yield.

For John Brown, the dividend yield is:

![]()

The dividend yield is perhaps comparable to the interest at the bank or building society. However, the increase or decrease in the share price over the year should also be borne in mind. The return from the dividend combined with the movement in share price is often known as the total shareholders’ return. Across the top 200 UK plcs in November 2001, the dividend yield was 4.1%.

(ii) Dividend Cover

This represents the ‘safety net’ for ordinary shareholders. It shows how many times profit available to pay ordinary shareholders’ dividends covers the actual dividends. In other words, can the current dividend level be maintained easily? For John Brown we have:

![]()

Thus, dividends are covered three times by current profits. As Company Snapshot 9.2 shows, J.D. Wetherspoon's dividend is well covered by profit available. Across the top 200 UK plcs in November 2001, dividend cover was 2.5.

(iii) Earnings per Share (EPS)

Earnings per share (EPS) is a key measure by which investors measure the performance of a company. Its importance is shown by the fact that it is required to be shown in the published accounts of listed companies (unlike the other ratios). It measures the earnings attributable to a particular ordinary share. For John Brown it is:

![]()

Each share thus earns 20 pence. Company Snapshot 9.3 shows that GSK's EPS was 32.1p in 2010. In this case, the number of ordinary shares is adjusted for the fact that some share options may be taken up to create new shares. This is called diluted EPS. Across the top 250 UK plcs in July 2005, EPS was 32.0 pence.

(iv) Price/Earnings (P/E) Ratio

This is another key stock market measure. It uses EPS and relates it to the share price. A high ratio means a high price in relation to earnings and indicates a fast-growing, popular company in which the market has confidence. A low ratio usually indicates a slower-growing, more established company. If we look at John Brown, we have:

![]()

Basic and adjusted earnings per share have been calculated by dividing the profit attributable to shareholders by the weighted average number of shares in issue during the period after deducting shares held by the ESOP Trusts and Treasury shares. The trustees have waived their rights to dividends on the shares held by the ESOP Trusts.

Adjusted earnings per share is calculated using results before major restructuring earnings. The calculation of results before major restructuring is described in Note 1 ‘Presentation of the financial statements’.

Diluted earnings per share have been calculated after adjusting the weighted average number of shares used in the basic calculation to assume the conversion of all potentially dilutive shares. A potentially dilutive share forms part of the employee share schemes where its exercise price is below the average market price of GSK shares during the period and any performance conditions attaching to the scheme have been met at the balance sheet date.

The numbers of shares used in calculating basic and diluted earnings per share are reconciled below.

Source: GlaxoSmithKline, Annual Report 2010.

This indicates that the earnings per share is covered three times by the market price. In other words, it will take more than three years for current earnings to cover the market price. Across the top 200 UK plcs in November 2000, the P/E ratio was 36.

The P/E ratio is shown in the financial pages of newspapers along with dividend yield and the share price. In Real-World View 9.3, we show details from the Daily Telegraph for the aerospace and defence, automobiles and parts, and banks’ industrial sectors. This shows that the P/E ratio for aerospace and defence ranged from 10.7 to 145.2, while for banks it was much lower, from 6.8 to 15.00. This probably reflects the more cautious attitude of the stock market to banks following the financial crisis of recent years.

Net Profit Margins

Source: Daily Telegraph, 20 October, 2011.

Note: The figures from left to right show the 52 week highs and lows of the share, the price on 20 October, the change since 19 July, the dividend and the P/E (price/earnings) ratio.

(v) Interest Cover

This ratio is of particular interest to those who have loaned money to the company. It shows the amount of profit available to cover the interest payable on long-term borrowings. Long-term borrowings can be defined as either preference shares and long-term loans or simply long-term loans. We will use only long-term loans here. This ratio is similar to dividend cover. It represents a safety net for borrowers. How much could profits fall before they failed to cover interest?

However, it is worth pointing out that interest is paid out of cash, not profit. For John Brown, we have:

![]()

Loan interest is thus covered six times (i.e., well-covered). Profits would have to fall dramatically before interest was not covered. Over the top 250 UK public limited companies in July 2005, this ratio was 23.56. Tesco's interest cover is shown in Company Snapshot 9.4. An alternative to this ratio is cash flow cover which is net operating cash flow divided by annual interest payments.

Tesco PLC

Waltham Cross, EN8 9SL (England)

Source: FAME database. Tesco plc. Evolution of: Interest Cover (x) (2001–2010) Published by Bureau van Dijk.

Worked Example

Having explained 16 ratios, it is now time to work through a full example. In order to do this, we use the summarised accounts of Stevens, Turner plc in Figure 9.7 (last seen in Chapter 7). Although adapted slightly, these are essentially the accounts in Figure 7.15 for 20X1, however, we now have an extra year 20X2. The main change is that there are now two years’ figures and percentages (see below).

Vertical and Horizontal Analysis

Before calculating the ratios it is useful to perform vertical and horizontal analysis.

Vertical Analysis

Vertical analysis is where key figures in the accounts (such as sales, statement of financial position totals) are set to 100%. The other figures are then expressed as a percentage of 100%. For example, cost of sales for 20X1 is 135, it is thus 39% of revenue (i.e., 135 of 350). Vertical analysis is a useful way to see if any figures have changed markedly during the year. Real-World View 9.4 presents a graph using vertical analysis for Tesco's 2010 results. In this case, total assets are shown as 100%. In addition, Tesco's liquidity ratio (probably current ratio) and gearing are compared to that of other retailers.

Vertical Analysis at Tesco

Source: FAME Database. Tesco plc. Structure of the balance sheet 2010. Published by Bureau van Dijk.

In Stevens, Turner plc, in 20X2, we can see from the income statement that loan interest and administrative expenses represent 2% and 22% of revenue, whereas in the statement of financial position, in 20X2, property, plant and equipment represent 75% of total net assets. We need to assess whether or not these figures appear reasonable.

Horizontal Analysis

Whereas vertical analysis compares the figures within the same year, horizontal analysis compares the figures across time. Thus, for example, we see that revenue has increased from £350,000 in 20X1 to £450,000 in 20X2, a 29% increase. We need to investigate any major changes which look out of line. For example, why have there been so many changes in current assets: inventories, trade receivables, and cash have all changed markedly (i.e., inventories up 68%, trade receivables down 52% and bank down 60%)? These may represent normal trading changes, or then again …

Interpretation

We will now work through the various categories of ratio (shown in Figures 9.8 to 9.13). We present them in tables and then make some observations. When reading these it needs to be borne in mind that normally these observations would be set in the context of the industry in which the company operates and in the economic context. They should, therefore, be taken as illustrative not definitive. We will use the available data. This is most comprehensive for 20X2 (as we can use the 20X1 comparative data).

(i) Profitability Ratios

Brief Discussion

Essentially, these profitability ratios tell us that Stevens, Turner plc's return on capital employed is running at between 18% and 25%, having increased over the year. This represents the return from the net assets of the company. Meanwhile, the business is operating on a high gross profit margin. This has also increased over the year. Finally, the net profit ratio has also increased, perhaps because the relative cost of sales has reduced.

(ii) Efficiency Ratios

Brief Discussion

There have been substantial reductions in the trade receivables and trade payables collection periods. Trade receivables are now paid in 48 rather than 83 days. By contrast, Stevens, Turner pays its trade payables in 170 days not 216 days. By receiving money more quickly than paying it, Stevens, Turner is benefiting as its overall bank balance is healthier. However, it must be careful not to antagonise its suppliers as 170 days is a long time to withhold payment. Inventory is moving more slowly this year than last. However, each inventory item is still replaced 4½ times each year. Finally, the asset turnover ratio is disappointing. Revenue is considerably lower than total assets, even though there is some improvement over the year.

(iii) Liquidity Ratios

Brief Discussion

There is a noted deterioration in both liquidity ratios. The current ratio has fallen from 2.2 to 1.8. Meanwhile, the quick ratio has declined from 1.9 to 1.1. While not immediately worrying, Stevens, Turner needs to pay attention to this.

(iv) Gearing Ratio

Brief Discussion

Gearing has declined over the year from 30.7% to 27.4%. In 20X2, 27.4 pence in the £ of the long-term capital employed is from borrowed money, rather than 30.7 pence last year. This change is due to the increase in retained earnings during the year.

(v) Cash Flow Ratio

(vi) Investment Ratios

Brief Discussion

More cash is flowing out than is flowing in. The main reason for this is the purchase of property, plant and equipment. The dividend yield is quite low at around 2% to 3%. However, it must be remembered that the share price has increased rapidly by 50p, and it is unusual to have strong capital growth and high dividends at the same time. Both dividend cover and interest cover are high. If necessary the company has the potential to increase dividends and interest. Earnings per share (EPS) has increased over the year and is now running at an improved 51 pence. It is this rise in EPS which may have fuelled the share price increase. The P/E ratio, however, is still very modest at 2.9.

Company Specific Ratios

The ratios provided in this chapter are widespread, but there is no standard set of ratios that are used for all companies. This makes sense as, for example, an airline will operate very differently from a mobile phone operator and ratios need to reflect this. In Company Snapshot 9.5 the key ratios and economic indicators used by Nokia, the mobile phone operator, are recorded. As can be seen, some ratios are relatively standard (e.g., return on capital employed), but some are more specialised (e.g., R&D expenditure as a % of net sales).

Report Format

Students are often required to write a report on the performance of a company using ratio analysis. A report is not an essay! It has a pre-set style, usually including the following features:

- Terms of reference

- Title

- Introduction

- Major sections

- Recommendations

- Appendices.

Figure 9.14 illustrates a concise overall report on Stevens, Turner plc for 20X1 and 20X2.

A real report would be longer than this, but this report gives a good insight into the use of report format.

Holistic View of Ratios

So far we have looked at individual ratios. However, although useful, one ratio on its own may potentially be misleading or may even be manipulated through creative accounting. Therefore, there have been attempts to look at ratios collectively. Two main approaches are briefly discussed here.

1. The Z Score Model

The idea behind this model, which was first developed in the US, is to select ratios which when combined have a high predictive power. In the UK, an academic, Richard Taffler, developed the model using two groups of failed and non-failed companies. After a comprehensive study of accounts, he produced a model for listed industrial companies. This model proved successful in distinguishing between those companies which would go bankrupt and those companies which would not.

2. Pictics

Pictics are an ingenious way of presenting ratios. Essentially, each pictic is a face. The different elements of the face are represented by different ratios. Real-World View 9.5 demonstrates two pictics.

Pictics

Source: Richard Taffler, Changing Face of Accountancy, Accountancy Age, 2 May 1996, p. 17.

The face on the left represents a successful business while that on the right is an unsuccessful business. The size of the smile represents profitability while the length of the nose represents working capital. Pictics are an easy way of presenting multi-dimensional information. Although it is easy to dismiss pictics as a joke, they have proved remarkably successful in controlled research studies.

Performance Indicators

The conventional mix of ratios may be unsuitable for some businesses, in particular those where non-financial performance is very important. Examples of such organisations include the National Health Service and the railways. Such businesses use customised performance measures often called performance indicators. For the National Health Service, indicators such as number of operations, or bed occupancy rate, may be more important than net profit.

Performance Indicators

Which performance indicators do you think would be useful when assessing the performance of individual railway operating companies?

Potentially, there are many performance indicators. For example:

- Percentage of trains late

- Miles per passenger

- Volume of freight moved

- Passengers per train

- Number of complaints

- Number of accidents

Organisations like the rail companies need to balance financial considerations (such as making profits for shareholders) with non-financial factors (such as punctuality). As Company Snapshot 9.6 shows, rail operating companies consider factors such as punctuality and UK rail customer satisfaction. They may also consider factors such as passenger and train numbers and income from fares and subsidies.

Limitations

Ratio analysis can be a useful financial tool. However, certain problems associated with ratio analysis must be appreciated.

1. Context

Ratios must be used in context. They cannot be used in isolation, but must be compared with past results or industry norms. Unless such a comparative approach is adopted ratio analysis is fraught with danger.

2. Absolute Size

Ratios give no indication of the relative size of the result. If net profit is 10%, we do not know if this is 10% of £100 or 10% of £1 million. Both the ratio and the size of the organisation need to be taken into account.

3. Like with Like

We must ensure that we are comparing like with like. The accounting policies of different companies differ and this needs to be appreciated. If companies A and B, for example, use a different rate of depreciation then a net profit of 10% for company A may equal 8% for company B.

4. International Comparison

The comparison of companies in different countries is even more problematic than same-country comparisons. The economic and business infrastructure in Japan, for example, is very different from that in the US. Traditionally, this has led to the current ratio in the US being much higher than in Japan.

Despite the above limitations, ratios are widely used. As Real-World View 9.6 shows, even though these accounting ratios are based on significant assumptions and varying underlying principles, they are still commonly employed by banks, credit rating agencies and other users.

Financial Ratios

Those of us with a grounding in accounting already know that financial information, although often (and naively) assumed to be precise, is necessarily based on significant assumptions and varying underlying principles. This means that accurate financial comparisons between companies (even those within the UK) cannot be made without a considerable amount of additional research and even restatement. In a cross-border analysis situation, the problem is further compounded by important accounting differences.

Despite this, traditional performance indicators such as profit margin, return on capital employed (ROCE), earnings per share (EPS) and the price earnings (P/E) ratio are widely published and used in decision making, often one suspects without any great attention being paid to what lies behind them. For example, banks, credit rating agencies, auditors, investment analysts, merger and acquisition teams and the financial press all use such financial ratios in their daily work.

Source: This article was published in Management Accounting by authors: M. Gardiner and K. Bagshaw, Financial Ratios: Can You Trust Them?, September 1997, page 30. ISSN - 0025-1682. Copyright Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA), 1997. Reproduced by Permission.

5. Validity of the Data

The reliability of the ratio analysis also depends on the reliability of the underlying data. This needs to be complete, comparable and accurate. This is particularly difficult for international comparisons.

Conclusion

Ratio analysis is a good way to gain an overview of an organisation's activities. There is a whole range of ratios on profitability, efficiency, liquidity, gearing, cash flow and investment. Taken together these ratios provide a comprehensive view of a company's financial activities. They are used to compare a company's performance over time as well as to compare different companies’ financial performance. For certain businesses, particularly those not so profit orientated, performance indicators provide a useful alternative to ratios. Performance indicators are often also used to supplement ratio analysis. When calculating ratios care is necessary to ensure that the underlying figures have been drawn up in a consistent and comparable way. However, when used carefully, ratios are undoubtedly very useful.

Discussion Questions

Discussion Questions

Questions with numbers in blue have answers at the back of the book.

| Q1 | What do you understand by ratio analysis? Distinguish between the main types of ratio analysis. |

| Q2 | Do the advantages of ratio analysis outweigh the disadvantages? Discuss. |

| Q3 | ‘Each of the main financial statements provides a distinct set of financial ratios.’ Discuss this statement. |

| Q4 | Devise a set of non-financial performance indicators which might be appropriate for monitoring:

(a) The Police (b) The Post Office (now known as Royal Mail in the UK) |

| Q5 | State whether the following are true or false. If false, explain why.

|

Numerical Questions

Numerical Questions

Questions with numbers in blue have answers at the back of the book.

Appendix 9.1: John Brown Plc

John Brown Plc has the following abridged results prepared for internal management use for the year ending 31 December 2012. The income statement and the statement of financial position are presented below.

At 31 December 2012 the market price of the ordinary shares was 67p.

APPENDIX 9.2: The Cash Flows Ratio using UK GAAP

Any Company Ltd has the following cash inflows and outflows in £000s:

To all intents and purposes, our total cash inflows thus match our total cash outflows.

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

Go online to discover the extra features for this chapter at www.wiley.com/college/jones

SOUNDBITE 9.1

SOUNDBITE 9.1 PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 9.1

PAUSE FOR THOUGHT 9.1 REAL-WORLD VIEW 9.1

REAL-WORLD VIEW 9.1

COMPANY SNAPSHOT 9.1

COMPANY SNAPSHOT 9.1