From Theory to Practice: Community Building

CoPs have been viewed as naturally forming, informal social phenomena. So, can we create CoPs? Creation implies developing something from nothing, and this is not a good approach to communities. Community building, however, differs from community creation. Where there is practice, there is community. The involvement of members or the depth of relationship in that community may be minimal, but the potential for community exists. Community building is not creating something from nothing; it is molding what exists and catalyzing previously unknown opportunities.

These activities are critical for two reasons. First, communities that have a relatively high degree of relationship and involvement can benefit from reflecting on their current status and how they can better achieve their desired goals. More important, however, is introducing community ‘novices’ to how the community model can enhance their work and practice. Particularly in companies with strong individualistic cultures, collaborative working and a sense of community may involve very foreign behaviors that must be learned. Community building, thus, can be viewed as learning how to learn organizationally.

Approaching community building

Community building is culture-dependent. The approach to community building that follows is based on the particular challenges inherent in one company’s culture. This approach could be called ‘cautiously prescriptive.’ Many of the frameworks and processes are modifications to or direct borrowings from the work of others, and the resulting frameworks have been shared with practitioners in a variety of industries to confirm their applicability. No framework, though, is ‘plug and play.’ All cultural interventions should be examined and interpreted in light of the particular cultural challenges and values of the target organization.

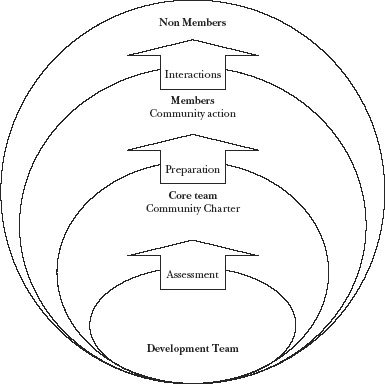

This approach considers community building learning community behaviors through expanding circles of intersubjectivity that narrow zones of proximal development in community participants. Intersubjectivity expands in four phases of meaning negotiation. First, the community development team, by defining philosophical underpinnings, development processes, and desired behaviors, creates a common understanding about what constitutes communities. While developing the framework, the team models community behaviors. Next, the development group works with a subset of the potential community to develop a sense of intersubjectivity concerning the specific practice and communities. This subset then expands the intersubjectivity circle to other potential members. Finally, community members, through their interactions with others outside the community, develop intersubjectivity with non-members. In addition, the foundation of intersubjectivity developed in the community serves to enculturate new members. Each step involves a Wengerian negotiation of meaning, blending participation and reification. At the same time, an ‘expert’ is able to scaffold the behaviors of other individuals in learning community activity, following the Vygotskian principles addressed earlier. Figure 10.1 depicts the expanding intersubjectivity circle and how groups interact during the development process.

Figure 10.1 Expansive Intersubjectivity in Community Development

The development process is systematic, yet evolving and flexible. It is built around an underlying philosophy of what constitutes community, how a community differs from other organizational structures (a community ‘vocabulary’), and methods for handling existing cultural elements that impact community behaviors. By approaching things systematically, the development team is better able to create a common understanding amongst potential community members of common goals and activities necessary to evolve a community. In the next sections, I will describe these frameworks and processes.

Defining communities

Language is critical to developing a sense of intersubjectivity (Rommetveit, 1974). Therefore, the first community development team task prior to facing any community is to define the term community of practice in order to more clearly communicate with potential members what constitutes this social structure and how it differs from others. In both the corporate and academic worlds, the word community has become confusing. Science students have been called a community of practice (Brown et al., 1993). Some groups in the work environment have been referred to as learning communities (Ryan, 1995). Online conversation groups have been referred to as virtual communities (Smith and Kollock, 1998). Even photography clubs or bridge groups have donned the title of CoPs. Use of the term community makes sense semantically since it characterizes well the groups’ unity of purpose.

Overuse of the terms community and community of practice can cause significant problems for community building, however—a lapse in intersubjectivity caused by misaligned vocabulary. Consider two groups in a corporation: a group of scientists responsible for product development and a photography club. Wenger and Snyder define CoPs as ‘groups of people informally bound together by shared experience and passion for a joint enterprise’ (2000: 139). According to this definition both groups are communities since members share a passion for their joint enterprises and have shared histories, experiences, and identities. Putting them on equal footing, however, creates potential discrepancies, because the socio-historical relationship between the scientists’ community and the organization and the photography club and the organization are different. The scientists’ community contributes significantly to the bottom-line profits of the company, and community goals may conflict with management desires and HR systems. Management designed as control systems that seek to direct all aspects of work may unknowingly interfere with community activities and growth. This is not the case with the photography club. The scientists’ community offers a much more complex development challenge than does the photography club.

Consistency in terminology is also a problem. As CoPs proliferate around a company, multiple memberships become commonplace. If the concept community differs radically from group to group, intersubjectivity about community life within the corporation will break down, and participation could be threatened.

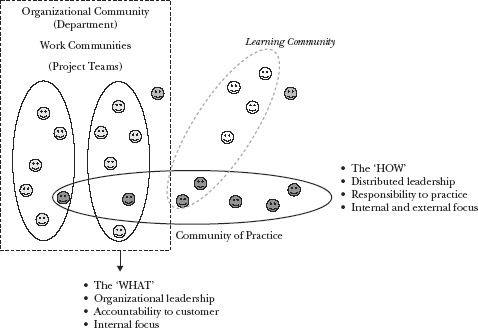

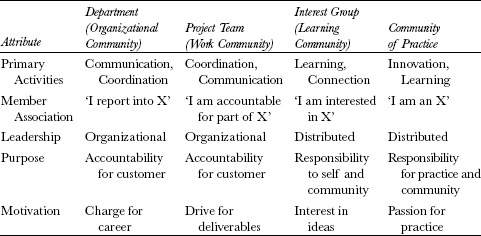

Arguing semantics in a company is difficult: people will continue to call any group a community. Two approaches can be taken to labeling communities: (1) distinguish among departments, teams, learning communities, and CoPs with those willing to discuss terminology, or (2) define community types for each social structure in the company. No matter how it is done, distinguishing structure types is critical. Figure 10.2 depicts the four organizational structures in this framework. Descriptions of these categories expand on work by Wenger and Snyder (2000).

Figure 10.2 Types of Social Structures

Most departments (organizational communities) are hierarchical in nature, driven by a reporting structure from employee to management to executive leadership. In general, they provide employee accountability structures and focus for the project work to create company profits. Employees identify with departments through their reporting structure and are driven by compliance systems, such as performance management, succession planning, and reviews. The primary departmental knowledge activities are communication and coordination concerning events, projects, promotions, strategy, and vision.

The project team is unified by a very specific goal—the creation of deliverables. Members are associated with the team through their accountability for a portion of the project. Management systems are similar to departments—performance directly affects succession, reviews, and salary increases; management is often hierarchical, with the project manager the ultimate decision maker. Though some teams have elements of community (common beliefs for example), many, influenced by systems of individual accountability rather than team responsibility, still have departmental trappings. The primary team knowledge activities are coordination of tasks, timelines, and resources and communication about constraints, changes, and barriers.

A learning community in this framework is an informal group that shares knowledge about a topic. The topic can be a computer program, a hobby, or a job task. The topic, however, is not the members’ dominant work activity. This community is not an organizational structure and is generally free from ties to management structures (performance management, salary increases, etc.), and leadership is distributed amongst the members. The primary learning community knowledge activities are learning and connection: sharing techniques or ideas, and networking expertise. The photography club treated earlier would be an example of a learning community.

The community of practice addresses critical work processes. Although some theorists see the fundamental purpose of a community of practice as learning (e.g. Wenger, 1998a) they are also engines for practice innovation and diffusion, since knowledge creation and learning are inseparable (Brown and Duguid, 1991; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Von Krogh et al., 2000). Project teams within departments produce the ‘what,’ the deliverable that ultimately provides profit, either directly or indirectly, for the company. The community of practice is orthogonal to the project team (see Figure 10.2), providing a venue in which practitioners from a variety of company settings commit to defining and refining their practice, or addressing the ‘how.’ This creates a double-knit organizational structure (McDermott, 1999).

CoPs are the identity containers and ‘shared histories of meaning’ (Wenger, 1998a: 89) for members of the corporation. While a learning community focuses on a supplementary skill, task, or interest, the community of practice focuses on the dominant work done by its members. Members identify themselves both inside and outside the corporation through their practice (‘I am a cardiologist,’ ‘I am an engineer,’ ‘I am a chemist’), and take ownership for their practice, driven by feelings of responsibility and passion for its quality and integrity. Table 10.1 summarizes the attributes of these four types of organizational structures.

Table 10.1 Attributes of organizational structures

Developing the community-building process

Once these discriminations have been made, the development team can then set its sights on developing a community-building process designed to foster intersubjectivity. The process presented here has three components: a stage model for community development, the APPLE development process, and the three dimensions of intersubjectivity. The stage model identifies how a community evolves over time, and is used to educate about community goals. The APPLE development process provides a step-by-step framework for moving a community along the development stages. The three intersubjectivity dimensions describe relationships within communities and serve as the guideposts for all the activities in both developing and maintaining a community. Each of the development components will be treated below.

Stages of community development

Wenger (1998b) defines five stages of development for a community: potential, coalescing, active, dispersed, and memorable. During the potential stage, individuals begin to find others with common interests but have no structure in which to share their experience. During the coalescing stage, the members begin to come together to define their practice, to define the function of their community, and to recognize the potential of their interconnections. During the active stage, the members develop the practice by defining artifacts, tools, creating relationships, and enhancing the practice. When members no longer engage in the practice, the community enters the dispersed stage. The members stay in contact and call each other for advice, but the community relationships dissipate. When the community is no longer viable, it enters the memorable stage, in which it completely dissipates, but the knowledge and experience still resides in its members who tell stories about the experience in the community and collect ‘memorabilia’ from it.

Wenger’s stage model provides a useful tool for educating potential community members and leaders, creating in them a sense of common goals and a common understanding of the development direction. An expansion to Wenger’s work is that the active stage can be divided into two parallel streams. Some communities are solely internally focused (Active I). The members create commitment and connection to each other and develop the practice, but the community scope is limited to its boundaries. They often remain anonymous or understated in the company. Some communities, on the other hand, see their role not only as innovating on their practice, connecting with others, and building competency, but also as influencing the company by publicly defining the role of their practice in the greater activities and business goals of the corporation (Active II). Their influencing may include changing work processes to better enable their effectiveness, lobbying for retaining or attracting staff, or even altering high-level decision making. They may also actively seek to partner with other communities to enhance their collaboration and the potential for radically changing their practice. Active II is not more evolved or advanced than Active I. These descriptors are merely used to help communities define their goals and needs. Figure 10.3 summarizes these stages of development.

APPLE process

Communities form naturally and will do so at the stage at which they are most comfortable (Wenger, 1999). A community-building process, however, can help catalyze the evolutionary process and provide guidance for more quickly reaching levels of interaction and involvement (Active I or II). Loosely based on traditional system design models, the development model presented here leads the developer and the community from identification of the situation through establishment of the community. The process bears the acronym APPLE to represent the five steps of the process: assessment, planning, preparation, launch, and establishment and evolution. Before treating these phases in detail, it is important to review the dimensions of intersubjectivity, since they form the framework for community-building activities.

Dimensions of intersubjectivity: the three Bs

Communities are founded upon relationships built on common understandings, vision, values, and beliefs, or intersubjectivity. The three pathways to intersubjectivity are intellectual, social, and emotional (Rogoff, 1990). Based on these three dimensions, this model puts forward the three Bs of community: believing, behaving and belonging.3 Each of these three dimensions informs activities from community start up to its continuing growth and evolution. These three components form a system; none can truly exist alone. The dimensions, however, can exist in varying degrees. The key is proper balance for the needs of the group. Segmenting community cohesion and intersubjectivity in this way enables members to identify existing imbalances and needed changes in community dynamics.

Believing

Believing encompasses the cognitive, thinking components of intersubjectivity. Key to believing is the establishment of the community identity and an understanding of the practice. The belief structure creates a common value system for the members, defines the community boundaries, and specifies how the practice holds strategic relevance for the enterprise in which it resides. Believing generally surfaces the specific problems that the community wishes to address and the mental models and body of knowledge needed to solve them. The focus areas should be both long term and short term, providing both a framework to strive for in the future and a specific set of problems to address in the present.

Believing questions

- What are the boundaries of the practice? What is ‘in’ and what is ‘out’?

- How is this practice relevant to the success of the enterprise as a whole?

- What are our values?

- What is our practice responsible for?

- What types of problems does the community wish to address?

Behaving

As the community develops, members establish ways of working with each other, tools in the domain, and processes and procedures in their practice. These behaviors become accepted by the community and guide communication, actions, and problem formulation for members. Behaving focuses on two components: behavioral norms and artifacts. First, there is a socially accepted way of performing tasks that, though it can be challenged by innovation, is solidly entrenched in the community members. Second, in performing these behaviors, members generate and use artifacts—tools, documentation, knowledge bases, websites, and applications—that can facilitate or expedite processes. The knowledge of the community is passed on to existing and future members by becoming embedded in these artifacts.

Behaving questions

- What knowledge should be shared, created, and documented?

- How should members share their insights with each other and collaborate on community work?

- What tools do members of the community currently use in participating in the practice and what tools need to be created to enable it further?

- How does the community determine what practices should be standardized?

- How does the community operate outside the boundaries of the company and the community?

Belonging

What people believe and how they behave creates a sense of belonging—an emotional feeling that they are part of joint enterprise with others of the same mind. Belonging is nurtured through personal relationships that must be developed and supported. Relationships, in this model, thrive on three elements: trust, equal representation, and understanding.

At the heart of productive work relationships and extensive knowledge sharing stands trust (Bukowitz and Williams, 1999; Handy, 1995; Lesser and Prusak, 2000). Accountability models drive most organizations. This type of model is built on an individualistic reward and punishment system, which, by creating an environment of judgment, often stifles risk taking and discourages sharing behaviors. Communities need to foster a sense of trust to counter these external forces, providing a safe environment for innovation, testing ideas, and knowledge sharing. Trust is fostered through deep relationships and through personal interaction and a personal ‘testing’ and understanding process.

Most organizations are hierarchically structured, with certain positions imbued with a level of power to direct, evaluate, decide, hire, and fire. With this stratification of power comes the potential for dissolution of trust at multiple levels and barriers to creating personal relationships required to develop a sense of belonging. Communities, by adopting a distributed leadership model, eliminating corporate ‘castes’ within their walls, and allowing all members of the practice to participate equally, develop thriving relationships.

Because multiple voices characterize the community structure, conflict and disagreement is a norm rather than an exception. Good communities turn disagreements into learning experiences and chances to foster understanding. Through managed conversations (Von Krogh et al., 2000), members express different opinions, approaches, and philosophies and find ways to reconcile differences, combine approaches, and create new knowledge.

Belonging questions

- What kinds of activities generate a sense of unity?

- How can members help each other?

- How can members generate trust with each other?

- How can the community become a safe place for members to try out ideas?

- What conflicts exist in the community and how can they help in sparking conversations?

- Do all members have an equal say? Are some members excluded?

- How are new members brought into the community and given a sense of belonging?

Assessment

The purpose of the assessment phase is to gather information about the current state of the existing or potential community to determine whether community building is necessary, and if so, what direction to take. Generally, communities develop initiators—practitioners who have been exposed to the concept and have taken it upon themselves to either spark conversations among practitioners or to seek out help in developing a community. These initiators serve as good information sources about the potential community. The assessment phase serves as a good opportunity to educate the initiators about community development. Dialogue between the development team and the initiators is the first opportunity to develop intersubjectivity about communities with potential members, positioning them to do the same with new members.

Several criteria determine community readiness: the maturity level (according to the stages presented earlier), geographic dispersion, technological comfort (if technology is to be used), and value to the business (if sponsorship needs to be gained). In addition to these criteria, the assessment should focus on the current levels of the three Bs. The perceived identity should be examined. Excitement and passion for the practice and certain topics within it can serve as entry points for community conversations. Questions about behaving reveal the current tools and ways that potential members interact, share knowledge, collaborate, and learn. Belonging questions focus on the current levels of trust and relationship among practitioners and how the various members or sites view each other. In some cases these data are difficult to gather directly from practitioners, especially if the relationships are negative. In these cases, observation of work processes is helpful as well as interviews with individuals who interact with the practitioners who are more objective and able to help describe the relationships they have observed.

From this data, a determination must then be made as to whether a community of practice is the right solution, if there is enough desire for community and passion for practice to sustain a community effort and whether the current situation can be changed enough to allow the community to be successful.

Planning and preparation

Once the initiators have determined that building a community would benefit the practice, they enter the most important and most intensive community-building activity—planning. During this phase the foundations for the community are laid. Once this strategic phase is completed, the community prepares for launch, specifying the tactical steps necessary for this event. Because the preparation phase is comprised of relatively mundane tasks, it will not be covered in depth here.

The planning phase is critical to community success. Because this work lays the foundation for the future of the community, commitment and attention to this phase cannot be overemphasized. It involves three major tasks: building the core of the community, developing the community charter, and developing strong community relationships.

Building the core group

The first task during this phase is to build a core group. The core group serves as the generator of the community charter and as the engine for the community. The core group can be analogized to the founders of a company. As the founding leadership of a company determines its culture (Schein, 1992), so the core group of the community determines the culture of the community. Therefore, extreme care must be taken in bringing members into the core.

Core group members should have a number of characteristics. The core group should represent a mix of experienced (five years’ tenure) and inexperienced members of the practice. Also, if the community spans multiple organizations, and most do, the core group should represent a mix of these organizations. This composition provides an innovative spirit that is informed and balanced by experience. Second, core group members should personally be willing to participate actively, share willingly, and influence others to participate. Both passion for the community enterprise as well as a willingness to network with others helps to build enthusiasm and recruit new members into the community. Finally, some core group members should be well-respected members of the practice to give legitimacy to the enterprise.

As with any organization, involving too many members too fast prevents efficient development of intersubjectivity and relationships. Between five and ten core group members is optimal. During their recruitment, they should be educated about the development process, what their role will be, and how they can help contribute to community success.

To both build relationships and to develop the common understanding about community work, the community development staff conducts an all-day session, the result of which is the community charter. During this all-day session, the key points and benefits of CoPs are reviewed. For learning about communities, analogies prove very helpful in developing an understanding about communities and the community values beginning to surface. Communities in the workplace have much in common with communities outside of it. Business people participate in communities on a regular basis outside of work. Yet, they often do not make the connection between these communities and communities in the workplace. Analogies help to make this connection.

One analogy compares building a community to creating a city. Most large cities were formed near rivers that provide a lifeline of trade and a source of water and food. In the same way, communities in corporations congregate around a ‘river’—a passion or need, either that enhances the social environment or ensures the ‘survival’ of workers by enabling them to do their jobs better. For community developers, the surveyors of the land, the task is to discover the ‘rivers’ where people congregate. Once discovered, the land must be surveyed, discovering the enabling peaks and distracting valleys, the dangerous mysteries of difficult relationships and the hidden treasures of passionate advocates and storehouses of knowledge. Once the terrain is determined, the boundaries are laid—the purpose and domain of the community. Finally, the social norms of the city are established—the behaviors and ground rules of the community. In the same way that a city’s life evolves and is socio-historical in nature, so is the development of a community. The city continues to grow and change, and so does the community. This analogy helps the core group clearly understand the process of community development.

The second analogy provides a discussion activity during the all-day session. Core group members mentally leave the workplace and examine communities outside of work. First, they think of a community to which they currently belong. They then list what keeps them engaged in that community. Then, they think of a community that they consciously left, and they list why they left. In debriefing these ‘attributes’ of community, the core group becomes aware of some of the key enablers and barriers that create or prevent communal relationships. Not only does this align core group members about the definition of community, but it also serves as a basis for the values of their own particular community.

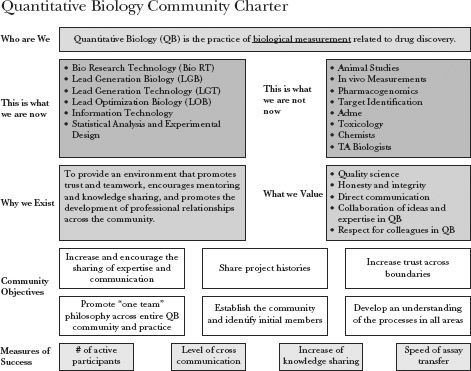

Developing the charter

The charter generated in the all-day session serves as the community’s externalization of its conception of the three Bs. The charter is generated through active brainstorming activities and negotiation by the entire core group, and must have the fingerprints of all members. It is comprised of six components. The Description of the Practice provides a concise description of the practice on which the community is based. Boundaries contain a brief listing of who (or what) is part of the community (within its boundaries) and who or what is not (outside its boundaries). Reason for Existence describes an overarching statement about the purpose of the community. Values hold a concise statement or list of what the community believes is important and what value it brings to the company. Objectives enumerate a list of specific, measurable objectives that the community wishes to achieve. Generally these address specific issues in the practice. Measures of Success lists indicators that the community is achieving its objectives. Figure 10.4 is a sample charter from one of our communities.

Figure 10.4 Quantitative Biology Charter

Once the blueprint has been established, the group prepares to share its work with the rest of the community and to involve other members. The preparation phase educates the extended world of practitioners with the value of community. If the group decides to launch the community with a meeting, the meeting agenda is prepared, the activities are identified, and the logistics are addressed.

Building relationships in the core

The activities that generate the charter naturally develop relationships amongst members. Following the creation of the charter, a number of activities can continue this process. Beginning to work on specific projects to benefit the practice, conducting sharing meetings, continuing to strategize how to build the community, and working collaboratively on work projects can not only help build relationships, but can begin to demonstrate and embody the principles and desired behaviors of the community prior to launch. Launch should not occur until the core group members have established strong relationships and had time to behave as community members.

Launch

The launch of the community has four major purposes. First, it serves as a way of recruiting new members into the community—of bringing those from the periphery toward the core. Second, it tests whether the charter is compelling. If feedback from potential members shows confusion or resistance, the core group may need to revisit the community charter. Third, it educates the organization about communities and how they can benefit the organization. Finally, it represents an intersubjectivity transition point. The core group members begin to take responsibility for community education and developing intersubjectivity about communities and their specific community with potential members. The community developer transitions into a consultant and coach.

The launch can take a variety of forms. A ‘metaphoric event’ is very effective. The community charter can be communicated in the context of a meaningful metaphor, rather than in a formal business meeting. One of our communities created a small neighborhood. Participants followed a ‘bus pass’ that directed them to different venues, at which core group members explained a portion of the charter. The optometrist’s office housed the vision. At the bank, participants learned about values. By the time participants completed the trip, they were well-acquainted with the purpose, activities, vision, and members of the community. Another group used the Olympics as its context, with each game serving as a discussion point. Others have used a presentation format. The preparation phase mentioned earlier is used to delegate tasks and design this event.

Certain messages should be delivered at launch. First and foremost, the community values and member commitment must be clearly communicated. Potential members need to understand that community is commitment to a set of values, a vision, and relationships. Second, management’s expression of support can give the community legitimacy. Because communities are a different way of working, some individuals need to know that it is acceptable for them to participate. Communication from a member of management (however, not an insistence on participation) is helpful in sending this message. Third, core group members should make clear that active participation in the community is optional, yet desired. Finally, the core members should ensure that potential members of the community know that the charter and the community can and must evolve and change. The work done by the core group only serves as a base from which to grow. All members have a say in that evolution.

The launch meeting often results in attracting a few to the community concept. Immediate involvement of these individuals is critical. Growth, however, needs to be monitored carefully. Some may still not be attracted to the concept. This resistance naturally helps to control growth. Community growth and evolution is a complex topic worthy of its own treatment.