Organizational learning is a change in the organization’s knowledge that occurs as it acquires experience (Fiol and Lyles, 1985). Researchers have taken different approaches to assessing organizational learning and the knowledge that results from it. Taking a cognitive approach, researchers have measured organizational learning by assessing changes in the cognitions of organizational members (Huff and Jenkins, 2001). Taking a behavioral approach, researchers have studied how organizational routines or practices change as a function of experience (Gherardi, 2006; Levitt and March, 1988) or how characteristics of performance, such as speed or accuracy, change as a function of experience (Argote and Epple, 1990; Dutton and Thomas, 1984). Researchers have also measured knowledge by measuring characteristics of an organization’s patent stock (Alcacer and Gittleman, 2006) or products (Mansfield, 1985).

Learning occurs at different levels of analysis in organizations: individual, group, organizational, and inter-organizational. We focus on learning at the organizational level of analysis but include research on group learning that sheds light on organizational learning (for reviews on group learning, see Argote, Gruenfeld, and Naquin, 2001; Edmondson, Dillon, and Roloff, 2007). Research on group learning is relevant for understanding organizational learning because groups are basic building blocks of organizations (Leavitt, 1996). Understanding learning within and between groups advances our understanding of organizational learning.

Although organizational learning generally occurs through individuals, individual learning does not necessarily imply that organizational learning has occurred. In order for organizational learning to occur, the individual would have to share knowledge with other organizational members or embed it in a repository that other members could use. That is, an individual’s knowledge would have to be embedded in a supra-individual repository such as a routine or a transactive memory system that other members could access.

Because our focus is on learning within organizations, research on inter-organizational learning is beyond the scope of this chapter (see Miner and Haunschild, 1995; Ingram, 2002; and Easterby-Smith, Lyles, and Tsang, 2008, for reviews). A major component of the literature in inter-organizational learning focuses on the concept of absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990) or the ability of an organization to recognize and assimilate information from external sources. Volberda, Foss, and Lyles (2010) provided a review and theoretical integration of research on absorptive capacity. Organizational learning and knowledge transfer in the context of alliances or joint ventures is also beyond the scope of this chapter (see Lavie and Miller, 2008; Zollo and Reuer, in press; Rosenkopf, 2000; Powell and Grodal 2005; Rosenkopf and Schilling, 2007).

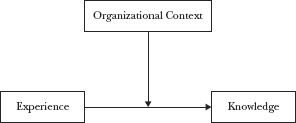

A framework for analyzing organizational learning is shown in Figure 29.2. It builds on a theoretical framework developed by Argote and Miron-Spektor (in press). As can be seen from the framework, organizational learning begins with experience and depends on the context. That is, the context moderates the relationship between organizational experience and knowledge. We focus on the moderating effect of the context on the relationship between experience and knowledge in this chapter. Other relationships in the overall framework, such as how knowledge affects the context which in turn shapes future experience, are discussed in Argote and Miron-Spektor (in press). Major components of Figure 29.2 are now discussed.

Figure 29.2 A Framework for Analyzing Organizational Learning

Experience

Experience is what occurs in the organization as it performs its tasks. Experience can be measured by the total or cumulative number of task performances. Several types and dimensions of experience have been proposed (Argote and Ophir, 2002; Argote and Todorova, 2007; Ingram, 2002; Schulz, 2002). In the current chapter, we focus on the extent to which experience is geographically distributed. The other important dimension of experience that we analyze in this chapter is whether experience is acquired directly by the focal organizational unit or indirectly from the experience of other organizational units. The latter form of learning is referred to as vicarious learning (Bandura, 1977) or knowledge transfer (Argote and Ingram, 2000).

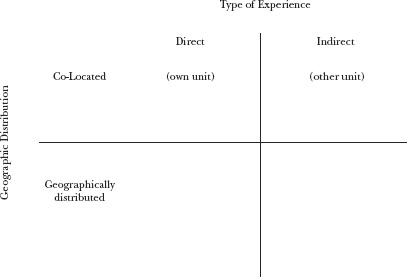

These two dimensions can be crossed as is shown in Figure 29.3. In the upper left quadrant of the table, members of organizational units are co-located and learn from their own experience. For example, co-located members of a product development team learn from its own direct experience developing products. In the lower left corner, members of organizational units are geographically distributed but work together on the same units of experience or task performance. For example, a geographically dispersed product development team that learns from its own experience designing a product would fit in this quadrant. In the upper right quadrant, a product development team would learn from the experience of other co-located product development teams in the same establishment. By contrast, in the lower right quadrant, a product development team would learn from the experience of other product development teams in geographically different locations.

Figure 29.3 Experience domain

Thus, the difference between the left and right columns of Figure 29.3 is whether one is learning from one’s own experience or from experience acquired by other organizational units. Organizations are made up of different groups and departments who can learn from their own experience as they perform a task or learn from the experience of other organizational units. The difference between the upper and lower rows of Figure 29.3 is geographic distribution: whether the organizational units are co-located or geographically dispersed. For purposes of this chapter, we define co-location as being part of the same establishment (i.e. an office building or campus).

Although the effect of experience on learning outcomes is generally beneficial (Argote and Epple, 1990; Dutton and Thomas, 1984), organizations vary dramatically in their ability to learn. In some organizations experience is associated with significant increases in knowledge, while in other organizations experience has little effect on knowledge or organizations learn the wrong knowledge. Experience can be challenging to interpret (March, Sproull, and Tamuz, 1991; Starbuck, 2009). Organizations sometimes derive inappropriate inferences from experience (Zollo, 2009; Tripsas and Gavetti, 2000). Levitt and March (1988) described the inappropriate lessons organizations can draw from experience as ‘superstitious learning.’ This sort of learning can occur when units are geographically distributed, which poses challenges to interpreting experience.

Organizational learning processes translate experience into knowledge. Organizational learning processes have been characterized in terms of their ‘mindfulness.’ Mindful processes are deliberative processes (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2006) while less mindful processes are automatic or routine ones (Levinthal and Rerup, 2006). Learning from both direct and indirect experience can occur in a mindful or less mindful way. Reflecting on experience, such as through after-action reviews, would be an example of mindful learning from direct experience. Stimulus-response learning would be an example of a less mindful process. Concerning learning from indirect experience, knowledge transfer attempts that adapt the knowledge to the new context would be mindful while ‘copy exactly’ approaches would be less mindful.

Context

The context includes the external and internal environments in which the organization is embedded. Competitors, clients, suppliers, trade associations, regulators, and nation states are part of the organization’s external environment. The context also includes aspects of the organization’s internal environment such as its culture, structure, strategy, technology, identity, and memory system. We organize our analysis of the context in three areas: national context, technical context, and social context. We examine how the context interacts with experience to affect organizational learning. Thus, we identify contextual conditions that facilitate learning from geographically distributed experience and contextual conditions that impair such learning.

Knowledge

Knowledge acquired through learning can be embedded in different repositories such as individuals, routines, tools, and transactive memory systems (Argote and Ingram, 2000; Walsh and Ungson, 1991). Further, knowledge can be characterized along several dimensions (see Alavi and Leidner, 2001). For example, knowledge can range from explicit knowledge that can be codified (Zander and Kogut, 1995) to tacit knowledge that is difficult to articulate (Nonaka and von Krogh, 2009; Polanyi, 1962). Similarly, researchers distinguish between ‘know-what’ or ‘know-how’ (Edmondson, Pisano, Bohmer, and Winslow, 2003; Lapré, Mukherjee, and Van Wassenhove, 2000). Knowledge can also vary in its complexity (Novak and Eppinger, 2001), its uncertainty and causal ambiguity (Szulanski, 1996), and its decomposability.

Geographic distribution

Geographic distribution poses challenges and opportunities for organizational learning and knowledge transfer. For example, Hong, Snell, and Easterby-Smith (2009) analyzed knowledge transfer between the headquarters of a Japanese multinational and its subsidiary in China and described the crossing of syntactic (communication), semantic (interpretation), and pragmatic (interests) boundaries (Carlisle, 2004). Firms are increasingly organized in a geographically distributed fashion that requires crossing such boundaries.

Geographic distribution has several underlying dimensions. Gibson and Gibbs (2006) investigated the separate dimensions of geographic dispersion, electronic dependence, and national context and found that each dimension had a negative effect on innovation. When members are dispersed across different locations, they may not share common knowledge and taken-for-granted understandings that facilitate information exchange and learning from experience (Cramton, 2001; Sole and Edmondson, 2002). Members of distributed organizations may depend on electronic communication to accomplish tasks, which reduces social cues (Sproull and Kiesler, 1991) and communication richness, and thereby impairs coordination (Boh, Ren, Kiesler, and Bussjaeger, 2007). Trust may be challenging to maintain in geographically distributed teams where members do not interact face-to-face (Jarvenpaa and Leidner, 1999).

National diversity also can impede learning because members may have different norms for communication (Gibson and Gibbs, 2006) and identify with their nation rather than with the organization. For example, Louis Gallois, the CEO of Airbus, which has French, German, British, and Spanish locations, banned national symbols in the organization because he attributed coordination problems with the A380 aircraft to national identities. He eliminated national flags because they reinforced identity at the national level and aimed instead to create a superordinate identity at the organizational level (Clarke, 2007).

Temporal dispersion is another dimension that is often associated with the geographic distribution of organizations. Geographically distributed teams that span time zones encounter more difficulties communicating and coordinating than those in the same time zone. Working across different time zones can provide opportunities for cultural faux pas if holidays and ‘normal’ work hours are not thoughtfully considered. For example, a US team scheduled an early Friday morning meeting that would correspond to the afternoon in France. The French work week, however, is thirty-five hours and Friday afternoon was out of normal work hours for the French collaborators who were too respectful to point out the oversight (Olson and Olson, 2000). The effect of temporal dispersion may be more difficult to overcome than the effect of spatial dispersion (Espinosa and Pickering, 2006; Cummings, 2009).

Geographic distribution poses challenges to organizational learning and knowledge transfer, which depend on members’ abilities, motivations, and opportunities (Argote, McEvily, and Reagans, 2003). Geographic dispersion can reduce members’ abilities to interpret experience by reducing common knowledge and social cues. In geographically distributed organizations, members may be more committed to their local units than to the superordinate organization, which reduces their motivation to learn and transfer knowledge. Because of temporal and spatial differences, members may not have many opportunities to interact and share knowledge in geographically distributed organizations. Thus, members’ abilities, motivations, and opportunities to learn and transfer knowledge are likely to be lower in geographically distributed than in co-located organizations.

Although knowledge transfer across geographic boundaries is challenging, firms that are able to successfully transfer knowledge across geographic boundaries realize enormous advantages. For example, Cummings (2004) found that external knowledge transfer across units was more strongly related to performance when units were geographically distributed than when they were geographically concentrated. The different geographic locations exposed the groups to unique sources of knowledge that were very valuable in improving their performance.