The theory of a general management dominant logic is one conceptual framework for thinking about the process and results of cognitive simplification in top management teams. As Schwenk (1984) suggests, strategic decision making in top management teams is subject to cognitive simplification. Top management, as with all humans, employ simplifying decision-making heuristics, such as prior hypothesis bias, adjustment and anchoring, illusion of control, and representativeness, that decrease their ability to appreciate the true complexity of problems and select the best solution.

The dominant logic represents the shared cognitive map (Prahalad and Bettis, 1986) and strategic mindset of the top management team or the dominant coalition, and is closely associated with the processes and tools used by top management. There may be minor variations in the details of the individual cognitive maps among top management team members, but the major features conform. From a managerial viewpoint, the congruence in cognition among top management team members offers advantages of efficiencies, but inevitably, it also introduces the disadvantages of rigidity. For example, the dominant logic may be inappropriately applied in diversification moves or when there are changes in the core industry. As Sull (1999) has observed, good companies go bad because they insist only on doing what worked in the past.

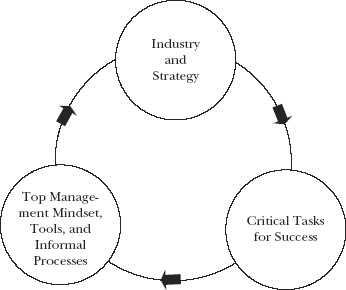

As shown in Figure 17.1, the dominant logic develops and evolves due to the characteristics of the industry and the strategy (or business model) the firm uses to compete in this industry. Essentially, experience and success in the presence of reasonable environmental stability breed shared patterns of thinking about key strategic and managerial issues. These shared cognitive patterns typically involve beliefs about issues such as causality in the industry, appropriate product cost structures, and desirable customer characteristics. As discussed below, this cognitive representation of the dominant logic eventually condenses or even ossifies into a variety of familiar organizational features where it takes on a highly durable and self-reinforcing nature. After condensation the dominant logic defines as much what the organization cannot do as what the organization can do (discussed below). The theoretical foundations of the shared mental encoding process lie in a variety of literatures including operant conditioning, decision heuristics, pattern recognition, cognitive simplification, and paradigms. The reader is referred to Prahalad and Bettis (1986) for an introductory discussion of some major foundation literatures.

Figure 17.1 Evolution of General Management Dominant Logic

The dominant logic concept also connects closely to the literature on complex adaptive systems (e.g. Axelrod and Cohen, 1999; Holland, 1995; Waldrop, 1992). Bettis and Prahalad (1995) point out that the dominant logic can be viewed as an emergent property of organizations. Such a view is entirely consistent with the cognitive mechanisms of individuals mentioned above. These cognitive mechanisms can be viewed as driving the micro-dynamics of agents in an organization. The outcome of these agents (senior managers) interacting with each other and with the common environment and common business model (or strategy) is seen at the aggregate level in the emergence of a dominant logic (and many other organizational properties). This emergence process is analogous to the way in which the particle mechanics of a large number of individual atoms within a gas interact with each other and the environment to produce emergent properties such as pressure and various thermodynamic relationships.

As an emergent property, it should be noted that the dominant logic is inherently an adaptive property as long as neither the domain of application nor the environment changes significantly. It allows the organization to ‘anticipate’ the environment by specifying the nature of cause and effect relationships. It economizes on managerial resources by simplifying and speeding decision making. However, this adaptive ability has obvious limitations and carries with it toxic side effects discussed below and in various references.

Condensation of dominant logic

This section examines how the dominant logic becomes embedded in the major features of the organization over time. The objective is to characterize the essential features of what we call the ‘condensation process.’ The objective is not to capture the complete complexity of this process and its relationship to a myriad of other issues.

The dominant logic develops over time. The process can be viewed as starting with the founding of a firm or with a major disruption of a firm (e.g. bankruptcy or near bankruptcy) that invalidates the dominant logic and management systems of a firm. As mentioned above and illustrated in Figure 17.1, there is an initial period during which the characteristics of the environment and firm strategy drive the formation of a shared mindset among the top management team. Obviously, in the presence of success (stability) this mindset becomes more uniform across managers and stronger over time. Up to this point the issue of significant change of the dominant logic is largely a matter of individual cognitive change across the top management team. This does not mean that change will be easy. However, it is likely to be much easier than when the dominant logic has condensed into a matrix of mutually reinforcing features within the organization.

As this mindset continues to develop, certain concepts and informal processes become associated with it within the top management team. For example, the authors have seen a firm in which ‘cost plus’ pricing became the only accepted way of thinking about pricing within the top management team. Also, the authors have observed firms in which the informal capital budgeting decision process among the top management team centered on rationing a percentage of sales proportionally across functions (e.g. manufacturing and sales). Increasingly the dominant logic places constraints on: (1) the search spaces associated with problems, (2) the conceptual frameworks used to help make decisions, and (3) the key features of acceptable solutions. The dominant logic at this point still remains largely invisible. It is cognitive with few or no obvious physical manifestations in the organization. It can only be examined through discussion with top managers and their direct reports.

As organizations grow and become more complex it becomes necessary and important to establish formal structure, procedures, systems, routines, and processes. These are usually designed in at least rough congruence with the dominant logic. In this sense the dominant logic begins to condense into ‘visible’ organization features. It also becomes ‘invisibly’ embodied as a significant part of the organization value system or culture. Formal structure, procedures, systems, processes, and controls are the hallmark of competent professional management. They standardize, simplify, and expedite decision making in line with the needs of the business. They focus attention on what are to be considered key issues. They establish priorities that conform to the strategic imperatives of the firm. In sum, they embody the dominant logic in the organizational features that direct attention and shape decisions for managers and employees throughout the organization.

By their very nature systems, procedures, controls, and processes are designed to be inflexible and difficult to change. Significant change in these features is undertaken only rarely, after considerable analysis, and at significant cost. Furthermore, they form a reinforcing web of relationships. For example, the job recruitment and selection routine, and organizational socialization process often result in the employment of individuals who share the organization’s beliefs and values. Like a form of social control (O’Reilly and Chatman, 1996), employees’ beliefs and interpretations of events, attitudes and behaviors become increasingly aligned with the dominant logic. This reinforces the existing systems, procedures, controls, and processes, which in turn fortifies the dominant logic.

Significant change in any one system, procedure, routine, control, or process is likely to require significant change in all or others to maintain alignment. All of these are interdependent (e.g. Siggelkow, 2001) to varying degrees, which makes the nature of relationships including causality difficult or impossible to discern. By contrast many techniques of change management, especially process reengineering have led many managers to conclude that major organizational changes are not all that difficult. However, as Christensen and Overdorf (2000) have observed, processes and systems are not nearly as flexible and adaptable as the proponents of these techniques suggest.

This process of condensation may take place over a considerable period of time with the dominant logic becoming more and more condensed. Once it has proceeded very far the problem of changing dominant logics becomes substantially more complex. As with physical solids, the process of moving back to a fluid state can require enormous amounts of energy if it can be accomplished at all. The condensation of a dominant logic is an irreversible process. One obviously cannot step backwards along the same path to the organization as it existed before condensation of the dominant logic. Change must involve creating a new path in the presence of a cognitive dominant logic and a mutually reinforcing web of ‘visible’ organizational features and a largely ‘invisible’ value system. Ultimately, this must involve unlearning of the inappropriate dominant logic. Success here is usually much more the exception than the rule. Dominant logics are extraordinarily resistant to unlearning.

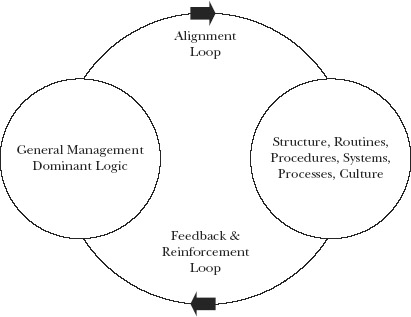

As illustrated in Figure 17.2, as the process of condensation moves forward, a reinforcing feedback loop is established. The structure, systems, routines, and processes designed largely to conform to the dominant logic now provide information, controls, incentives, values, and decision rules that mirror the dominant logic to a substantial degree. Top management receives information and decision agendas framed in congruence with the dominant logic. Information systems ensure that attention is allocated to issues deemed important by the dominant logic. Decision rules are established to conform to the dominant logic. Metrics are those deemed important by the dominant logic. Controls assure compliance with the dominant logic. Hence a substantial portion of the organization becomes a reinforcing and interdependent system built largely around the dominant logic.

Figure 17.2 Condensation of General Management Dominant Logic

The focus narrows throughout the organization. Thoughtful action and creative analysis are increasingly displaced by ‘unconscious’ rules, processes, values, and systems (Ashforth and Fried, 1988). The capability for thoughtful independent action atrophies and decisions increasingly become automatic and habitual. Doing different things or even doing things differently becomes more and more difficult for the organization. This is suggestive of the common observation that the more successful organizations become the more difficult they find it to change. Of course as long as there is no necessity to make significant change, the condensed dominant logic can provide a highly effective and efficient means of managing the organization. The organization tends toward simplification, where it gradually weeds out ‘unsuccessful’ practices and builds ‘architectures of simplicity’ (Miller, 1993). In an earlier era, aligning organizational characteristics with strategy was considered the major mechanism of strategy implementation. In fact this paradigm of tight and long-term alignment of organizational activities with a ‘semi-permanent’ strategy is still followed pedagogically in some MBA programs. This is fine as long as the strategy is robust to the environment, but when significant change is necessary, it will be intensely difficult.

With continuous reinforcement in place, condensation may move to a stage best described as ‘fossilization.’ The organization becomes merely a rigid physical imprint of something that was once alive and able to move and to respond to some degree to the environment. In this state performance must decline catastrophically before an attempt is made to respond. The usual result is the dissolution or acquisition of the organization.