Origins, Definitions, and Operationalizations

Even though Kedia and Bhagat (1988) were first to coin the term absorptive capacity, in the context of technology transfer across nations, Cohen and Levinthal (1989, 1990) are generally credited for forwarding the construct. The absorptive capacity construct evolved from research instigated in the 1970s and running through the 1980s on the role of internal research and development. Studies observed that internal research and development has a dual role. It not only shapes a firm’s technological innovation, but also allows firms to keep abreast of technological developments and assimilate new technology (Tilton, 1971). Consistent with studies using an Industrial Organization-based perspective to explain firm strategy, Cohen and Levinthal (1989, 1990) sought to provide a set of explanations for the dual role of research and development from that perspective. While their 1989 paper focused on firms’ incentives to learn and to invest in research and development as environmental opportunities vary from an economics perspective, their 1990 paper centered on the role of cognitive structures and took a more socio-economical approach. Borrowing from research on cognition and memory development (Ellis, 1965), in the latter paper they argue that individuals learn more efficiently when the knowledge to be learned is related to what is already known and emphasize the cumulative nature of learning.

Definitions

As our understanding of the construct has progressed over the years, the definition of absorptive capacity has evolved. An overview of most prominent definitions is given in Table 13.1. In their most widely cited paper, Cohen and Levinthal (1990: 128) define absorptive capacity as the ‘ability to recognize the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends.’ This definition derives from their earlier definition, which emphasizes the ‘ability to identify, assimilate and exploit knowledge from the environment’ (1989: 569–570). They further argue that this ability is ‘largely a function of the level of prior related knowledge’ (1990: 128). Firms that have in place a body of knowledge in a certain domain will improve learning related knowledge. In other words, a firm’s knowledge base renders three capabilities, which other studies have referred to as components (Lane et al., 2001) and dimensions of absorptive capacity (Lane and Lubatkin, 1998; Matusik and Heeley, 2005; Zahra and George, 2002). For a firm to have absorptive capacity it requires (1) the capability to identify, evaluate, and recognize the value of new external knowledge, (2) the capability to assimilate that knowledge into its existing knowledge base, and (3) the capability to exploit it to commercial ends.

Table 13.1 Definitions of absorptive capacity

| Study | Definition |

| Cohen and Levinthal (1990) | ‘an ability to recognize the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends’ (p. 128). |

| Lane and Lubatkin (1998) | ‘the student’s ability to value, assimilate, and commercialize its teacher’s knowledge’ (p. 473). |

| Zahra and George (2002) | ‘a set of organizational routines and processes by which firms acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge’ (p. 186). |

| Matusik and Heeley (2005) | ‘comprises . . . (a) the firm’s relationship to its external environment (porosity of firm boundaries), (b) collective dimension (its structures, routines, and knowledge base), and (c) an individual dimension (individuals’ absorptive capacities’) (p. 550). |

| Lane et al. (2006) | ‘a firm’s ability to utilize externally held knowledge through three sequential processes: (1) recognizing and understanding potentially valuable new knowledge outside the firm through exploratory learning, (2) assimilating valuable new knowledge through transformative learning, and (3) using the assimilated knowledge to create new knowledge and commercial outputs through exploitative learning’ (p. 856). |

| Lewin et al. (2010) | ‘internal metaroutines [that] involve the regulation of activities related to managing internal variation-selection-retention processes . . . [and] external metaroutines . . ., which focus on the acquisition and utilization of knowledge from the external environment’ (in press). |

| Todorova and Durisin (2007) | a firm’s ability to recognize the value of new knowledge, to acquire it, to assimilate and/or transform it, and to exploit it. |

| Lim (2009) | Absorptive capacity consists in three forms, of which ‘disciplinary absorptive capacity involves acquiring raw scientific knowledge in key scientific disciplines, and converting that knowledge into a form that is useful for solving practical problems, [while] domain-specific absorptive capacity refers to the ability to acquire knowledge directly related to solving those problems, so as to produce commercially useful innovations, [and] encoded absorptive capacity refers to a firm’s ability to absorb knowledge that is already embedded in tools, artifacts, and processes’ (p. 1252). |

Firms are not necessarily equally endowed with these capabilities and may not have in place all three capabilities to the same degree. To that end, Zahra and George (2002) forward absorptive capacity as a dynamic capability. Based on the studies of Mowery and Oxley (1995) and Kim (1998), they introduce a fourth capability in addition to the three capabilities identified by Cohen and Levinthal (1990) and define absorptive capacity as ‘a set of organizational routines and processes by which firms acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit knowledge’ (2002: 186). Their definition explicates that firms also need the ability to solve problems by transforming and modifying existing knowledge before they can exploit external knowledge. Based on the four capabilities, they make distinction between potential and realized absorptive capacity as two subsets of absorptive capacity that explain why firms vary in their ability to create value from their absorptive capacity. While potential absorptive capacity is a function of a firm’s ability to acquire and assimilate new external knowledge, realized absorptive capacity reflects a firm’s capacity to leverage that knowledge through transformation and exploitation. Minbaeva et al. (2003: 589) argue that ‘potential absorptive capacity is expected to have a high content of employees’ ability while realized absorptive capacity is expected to have a high content of employees’ motivation.’ Similar distinctions have been made between evaluation and utilization of knowledge (Arora and Gambardella, 1994) as well as between knowledge transfer and knowledge application (Bierly et al., 2009). Firms may have the ability to acquire and assimilate knowledge but lack the capacity to transform and exploit knowledge. Likewise, firms may have the capability to transform and exploit knowledge, but lack the capability to acquire knowledge from the environment. Such firms may be very efficient in realizing performance improvements, but the effect of their capability will be mitigated by the limited amount of external knowledge they acquire. Camisón and Forés (2010) found that potential and realized absorptive capacity are empirically distinct capabilities of absorptive capacity.

The empirical study of Jansen et al. (2005) indicates, however, that acquisition, assimilation, transformation, and exploitation should be viewed as four separate capabilities. Their four factor model was found to be superior to a two factor model revolving around potential and realized absorptive capacity. In their critique on the value of studying potential and realized absorptive capacity as two dimensions, Todorova and Durisin (2007) also make a case for considering the distinct capabilities as separate elements of absorptive capacity. Additionally, they suggest reintroducing the capability to recognize the value of external knowledge as originally put forth by Cohen and Levinthal (1990). Recognizing knowledge is implied by the acquisition capability identified by Zahra and George (2002). Todorova and Durisin (2007) make a case, however, that it is a separate process that elicits motivation to direct attention to the intensity, speed, and effort involved in acquiring knowledge. Moreover, based on research in cognitive science, they argue that transformation is not necessarily a process following but an alternative to assimilation. Even though Zahra and George (2002) also broadly imply this (see also Lane et al., 2006), Todorova and Durisin (2007) submit that firms may assimilate external knowledge without transforming it if it fits with the present knowledge base. In case new knowledge cannot be realistically altered to fit existing knowledge, firms may also need to transform knowledge before it is assimilated.

Showing how absorptive capacity aids firms in benefitting from knowledge spillovers, Lim (2009) delves into the processes revolving around the different capabilities constituting absorptive capacity. Specifically, he contends that absorptive capacity may be present in three forms: disciplinary, domain-specific, and encoded absorptive capacity. Disciplinary absorptive capacity refers to the acquisition of scientific knowledge and the transformation of that knowledge into useful forms for problem solving. Domain-specific absorptive capacity involves the ability to acquire additional knowledge to solve those specific problems, and to apply it to commercially useful innovations. Finally, encoded absorptive capacity denotes a firm’s ability to absorb knowledge that is already embedded in tools, artifacts, and processes.

Since the variety in the use of absorptive capacity has led to inconsistent findings, Lane et al. (2006) have sought to reify the absorptive construct. To that end, they define absorptive capacity as the ability to recognize and understand potentially valuable knowledge through exploratory learning, to assimilate valuable knowledge through transformative learning, and to create new knowledge and commercial outputs through exploitative learning. Absorptive capacity revolves around three learning processes that reflect the innovative nature of absorptive capacity as emphasized by Cohen and Levinthal (1990). Exploration of new knowledge is necessary for innovation, but needs to be transformed before firms are able to exploit it.

In an empirical study among 175 German firms, Lichtenthaler (2009) argues that the exploratory learning process involves recognition and assimilation, the transformative learning process associates with maintaining and reactivating knowledge, and the exploitative process is characterized by the transmutation and application of knowledge. In line with Jansen et al. (2005), he found that a model reflective of the basic elements is superior to a model of higher order dimensions. Specifically, a six factor model around capabilities to recognize, assimilate, maintain, reactivate, transmute, and apply knowledge was superior to a three factor model around exploratory, transformative, and exploitative learning. However, a model in which the three learning processes were included as second order factors of the six first order factors, which subsequently loaded on absorptive capacity as a third order factor, proved to fit the data best. With that, current insights suggest that absorptive capacity involves different capabilities.

Levels of analysis

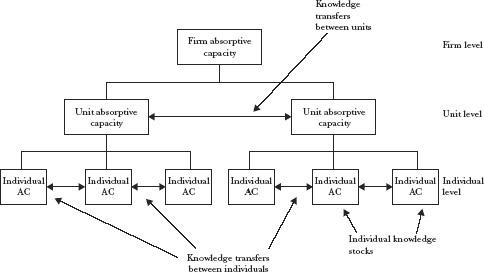

Prior research has shown that absorptive capacity is a construct operating at multiple levels. Cohen and Levinthal (1990) introduced absorptive capacity as a firm-level construct, but they emphasize that multiple levels are involved and focus on a firm’s organizational units to explain how it develops. Since individual members are involved with absorbing knowledge within firms, they forward that ‘an organization’s absorptive capacity will depend on the absorptive capacities of its individual members’ (1990: 131). Indeed, as Lane et al. (2006: 853–854) argue, ‘individuals within the firm . . . scan the knowledge environment, bring the knowledge into the firm, and exploit the knowledge in products, processes, and services.’ A firm is, however, a social community characterized by an architecture and organizing principles that make it more than a collection of individuals (cf. Kogut and Zander, 1992). Similarly, absorptive capacity ‘is not . . . simply the sum of the absorptive capacities of its employees, and it is therefore useful to consider what aspects of absorptive capacity are distinctly organizational’ (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990: 131). Similarly, Matusik and Heeley (2005) argue that a firm’s absorptive capacity has an individual and a collective dimension. While absorptive capacity is partly dependent on the knowledge and abilities of its individual members, it is also dependent on a firm’s knowledge that is collectively held in routines, procedures, documentation, systems, and shared experiences. Collective knowledge is defined by the discrete components of an organization’s operations or parts, and an organization’s architecture that enables how routines are developed to put a firm’s components to productive use.

Taken that absorptive capacity is dependent on a relevant knowledge base, the link between absorptive capacity and learning is most evident at the individual level. Cohen and Levinthal (1990) derive from cognitive research on memory development (Ellis, 1965) that individuals learn more when the object of learning is related to what is already known. Research on memory development has shown that accumulated prior knowledge enables the ability to store new knowledge into one’s memory and to recall and use it. The cumulative nature of learning and absorptive capacity entails that knowledge development is path-dependent and gives rise to specializations.

Since knowledge within firms is distributed among various individual members and subunits, firms have multiple entry points for external knowledge. Firms also coordinate interaction between individuals and subunits through communication structures, hence absorptive capacity ‘also depends on transfers of knowledge across and within subunits that may be quite removed from the original point of entry’ (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990: 131–132). Absorptive capacity rests, therefore, on individuals standing at the interface of both the environment and other subunits. In case external knowledge is dissimilar to what is known, an individual can consult other individuals within the organization that possess relevant related knowledge. In case the knowledge relates to what is known, individual members can translate knowledge in a meaningful way for others or relieve others from monitoring the environment. Cohen and Levinthal (1990) contend that organizations install group members that assume a gatekeeping or boundary-spanning role. Boundary spanners maintain ties that enable them to know where relevant knowledge resides in a firm and enhance individual performance in knowledge-intensive work (Cross and Cummings, 2004). Since a gatekeeper forms the point of entry and is dependent on the expertise of others within its group and the larger organization, designing a structure around gatekeepers cannot be disentangled from the distribution of expertise. The architecture that brings individuals together in groups and allows them to transfer knowledge and information renders a firm’s absorptive capacity more than the sum of the absorptive capacities of its individual members and dependent on the ties between them.

A number of studies have also begun to examine the role of absorptive capacity in intrafirm knowledge transfer at the unit or subsidiary level (Tsai, 2001). While subunits need prior related knowledge to be able to evaluate, assimilate, and exploit knowledge originating in the external environment, studies found that absorptive capacity is also a critical determinant of knowledge transfer among peer subunits (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000; Szulanski, 1996). Altogether, current insights illustrate that absorptive capacity is a phenomenon operating at multiple levels in an organization. As Figure 13.1 illustrates, absorptive capacity ‘depends on the individuals who stand [either] at the interface of . . . the firm and the external environment or at the interface between subunits within the firm’ (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990: 132).

Figure 13.1 Levels of Absorptive Capacity

Other relevant levels of analysis at which absorptive capacity has been studied include clusters of related industries, such as regions and nations (Wegloop, 1995), and even clusters of institutionally linked countries, such as the European Union (Meyer-Krahmer and Reger, 1999). Interaction among firms, universities, and governments in regions and nations shapes innovation infrastructures. To capitalize on such infrastructures, in different locations around the world clusters have emerged in which firms, universities, governments, and customers collaborate and drive innovation (Porter and Stern, 2001). Actors in a nation, region, or cluster have a stock of knowledge that creates absorptive capacity. Similar to collaboration among individuals shaping a firm’s absorptive capacity beyond the sum of the knowledge held by individuals, two-way interactions between firms, nations, and clusters further enhance the ability of the region to attract talented individuals, companies, and institutes that bring new expertise and knowledge. As such, increasing the absorptive capacity of the economy becomes an important aspect of public policy (Mowery and Oxley, 1995; Keller, 1996).

The notion that absorptive capacity shapes knowledge transfer both between and within firms is supported by Lane and Lubatkin (1998), but they forward that absorptive capacity should be studied at the dyad level and introduce relative absorptive capacity. They argue that the level of absorptive capacity of a firm is not only dependent its own knowledge base but also on the knowledge bases of its interacting partners. If the knowledge bases of two firms do not overlap, they will experience difficulty learning from each other. Especially in the context of alliances where competitive advantage rests with the dyad, absorptive capacity is essentially relative (Lane and Lubatkin, 1998) and even partner-specific (Dyer and Singh, 1998).

Operationalizations

One of the root causes inhibiting progress in our understanding of the value of absorptive capacity is that empirical studies have estimated absorptive capacity in a wide variety of ways (see Table 13.2). Cohen and Levinthal’s (1990) core argument centered on the role of in-house research and development in the acquisition of knowledge and in innovation. Therefore, they used business units’ research and development intensities as a proxy for measuring absorptive capacity. A large number of studies have also adopted research and development intensity as the measure for absorptive capacity (e.g. Nicholls-Nixon and Woo, 2003; Puranam and Srikanth, 2007; Zhang et al., 2007a). However, ‘R&D intensity measures inputs to the creation of capabilities and indicates little if anything about resultant changes in capabilities’ (Mowery et al., 1996: 82; Helfat, 1997). Research and development intensity only coarsely gauges a firm’s absorptive capacity and it is not fully reflective of the multidimensionality of absorptive capacity. Although research and development indeed develops a firm’s knowledge base, it neither differentiates between different domains in which knowledge is developed nor makes a distinction between capabilities to recognize the value, to assimilate, to transform, and to commercially exploit knowledge. Moreover, since research and development intensity is measured by dividing its expenditures by sales, it does not indicate the absolute amount of absorptive capacity. Following this train of thought, a firm spending one million dollars on research and development with sales of twenty million dollars would have a higher level of absorptive capacity than a firm spending twenty million dollars on research and development with sales of one billion dollars. However, the latter firm would arguably have developed more knowledge enabling it to assimilate new external knowledge, even though its research and development intensity is lower. To address the problem of the denominator influencing the results, other studies have focused on the numerator and used research and development expenditures as a gauge for absorptive capacity (Kamien and Zang, 2000), while controlling for size (e.g. Rothaermel and Alexandre, 2009; Rothaermel and Hess, 2007).

Table 13.2 Operationalizations of absorptive capacity

| Level of analysis | Operationalization | Sample studies |

| Firm level construct | R&D measures: R&D intensity |

Cohen and Levinthal (1989; 1990); Mowery et al. (1996); Nichols-Nixon and Woo (2003); Puranam and Srikanth (2007); Singh (2008); Stock et al. (2001); Tsai (2001); Zhang et al. (2007a) |

| R&D expenditures | Kamien and Zang (2000); Rothaermel and Alexandre (2009); Wiethaus (2005) |

|

| R&D infrastructure | Cassiman and Veugelers (2006); Lichtenthaler and Ernst (2007) |

|

| Patent stock | Almeida and Phene (2004); Bogner and Bansal (2007); Frost and Zhou (2005); Henderson and Cockburn (1996); Rosenkopf and Nerkar (2001); Somaya et al (2007); Zhang et al. (2007b) |

|

| Prior experience | Kusunoki et al (1998); Lenox and King (2004); Macher and Boerner (2006) |

|

| Proportion of foreigners/expats in management team | Gupta and Govindarajan (2000); White and Liu (1998) | |

| Scales | Björkman et al (2004); Camisón and Forés (2010); Haas (2006); Jansen et al. (2005); Lichtenthaler (2009); Lyles and Salk (1996); Szulanski (1996) |

|

| Publications | Cockburn and Henderson (1998); Deeds (2001) |

|

| Dyad level construct | Patent overlap | Ahuja and Katila (2001) |

| Technological relatedness/overlap | Mowery et al. (1996); Tallman and Phene (2007) |

|

| Scales | Lane and Lubatkin (1998) | |

| Publications/citations | Lane and Lubatkin (1998) |

Since patents are indicative of accumulated knowledge, another stream of research has used a firm’s stock of prior patents as a measure for absorptive capacity (e.g. Ahuja and Katila, 2001; Almeida and Phene 2004; Bogner and Bansal, 2007; Frost and Zhou, 2005; Yayavaram and Ahuja, 2008; Zhang et al., 2007b). Measures based on patents to assess a firm’s knowledge base create an opportunity to differentiate between different types of knowledge bases. For example, the number of patents is indicative of the depth and richness of a firm’s knowledge stock, while different patent classes can be used to measure the breadth and diversity of a firm’s knowledge stock (Almeida and Phene, 2004). Since data on patent stocks of all partners involved in a collaboration are generally available, studies have also used patent measures to assess overlap in patents (Ahuja and Katila, 2001), which is a proxy for relative or partner-specific absorptive capacity. Other measures used to assess the presence of relevant knowledge involve prior experience (Almeida and Phene, 2004), and the composition of management teams (Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000) and personnel (White and Liu, 1998).

Since the above measures appraise more than absorptive capacity and cannot differentiate between the various capabilities that firms need to be able to absorb knowledge, studies have resorted to using scales. While some studies have used scales to measure absorptive capacity directly as a singular construct (e.g. Lyles and Salk, 1996; Szulanski, 1996), more recently studies have begun to use scales to measure the various capabilities separately (e.g. Jansen et al., 2005; Lichtenthaler, 2009). Scales have also been used to assess a unit’s or firm’s knowledge stock (e.g. Björkman et al., 2004; Haas, 2006), as well as overlap in a firm’s knowledge and technology (Lane and Lubatkin, 1998; Mowery et al., 1996).

The use of such a variety of measures for absorptive capacity has obfuscated current insights. The proxies used seem to gauge phenomena beyond absorptive capacity and do not necessarily correlate. For example, the evidence on the relation between research and development intensity, the proxy for absorptive capacity used in the original studies of Cohen and Levinthal (1989, 1990), and other variables that measure the various capabilities or dimensions of absorptive capacity is mixed. While Bierly et al. (2009) found positive correlations for research and development intensity with what may be considered potential and realized absorptive capacity, others found no relationship (e.g. Lane and Lubatkin, 1998; Matusik and Heeley, 2005; Mowery et al., 1996). Similarly, Björkman et al. (2004) found a non-significant correlation between subsidiary stock of knowledge and number of expatriate managers in the subsidiary, both previously used measures of absorptive capacity (e.g. Gupta and Govindarajan, 2000; Haas, 2006). Kotabe et al. (2007) found a non-significant correlation between the quality of the knowledge stock and research and development resources, also two measures of absorptive capacity that have been used in earlier studies.

Even in studies relying on a single type of source, consistency in measuring absorptive capacity has proven to be paramount. Using a patent database, Frost and Zhou (2005) assess the extent to which a subsidiary unit and headquarters engage in joint technical activity by measuring research and development co-practice, which is viewed as a flow variable that adds cumulatively to the stock variable measuring citations by a headquarters patent to a prior subsidiary patent. In that vein, their study illustrates that absorptive capacity is cumulative and a by-product of research and development investments. However, they also measure patent output weighed by patent quality of both headquarters and subsidiaries, which are indicators of existing knowledge-based resources. In line with the argument that absorptive capacity is dependent on prior knowledge, both headquarters’ patent output stock in one period and headquarters’ citations to subsidiary patents in the next are possible estimates of absorptive capacity. The question is whether the quality-corrected patent output measure or the citation measure is the preferred operationalization. Inter-firm patent citations are often used as proxies for knowledge transfer (e.g. Jaffe et al., 1993; Kotabe et al., 2007; Nerkar and Paruchuri, 2005; Rosenkopf and Almeida, 2003; Song et al., 2003), of which absorptive capacity is an antecedent and not its equivalent. The patent output measure, on the other hand, only seems to capture a firm’s ability to exploit its knowledge, and not to evaluate and assimilate it. However, patent output determines the number of patents held by a firm, which have been used as measures of the knowledge held by a firm (Henderson and Cockburn, 1996; Rosenkopf and Nerkar, 2001) and innovative output (Ahuja, 2000; Rothaermel and Hess, 2007). Similarly, others have found a positive effect of research and development spending on co-citations (Deeds, 2001) and patenting performance as measured by counting patents (Somaya et al., 2007). While patenting performance is indicative of innovative performance, the count measure also gauges absorptive capacity as a higher patent count is reflective of a larger knowledge base. In contrast, using research and development expenditures and intensity respectively, Cattani (2005) and Singh (2008) did not find such a relation. While current insights support the argument that research and development spending has indeed a side effect in that it develops the knowledge base of a firm in addition to enhancing innovation, they are also indicative of the problems in operationalizing absorptive capacity. Altogether, different measures assess different dimensions of absorptive capacity as well as elements of which absorptive capacity is an antecedent or outcome.