Chapter 2

Sweden and its media scene, 1945–90

A bird's-eye view

Karl Erik Rosengren

Sweden is a relatively large country with a small population (some 450,000 square kilometres and some 9 million people; cf. United Kingdom: some 245,000 square kilometres, some 57 million people). The population is concentrated in the southern parts of the country, where the three largest cities are situated, including the capital, Stockholm. This concentration is traditional, but it increased during the first decades after the Second World War. At the same time, central authorities increased their power considerably, partly as a consequence of systematic efforts by the Social Democrat governments of those decades. In spite of strong efforts at decentralization during the 1970s and 1980s, and a process of deregulation in the early 1990s, there is no denying that compared to many other countries Sweden is still highly centralized in many respects. (For some basic information about Sweden, see, for instance, Hadenius 1990; Hadenius and Lindgren 1992.)

At the time of writing (1992/93), Sweden – just like most other European countries – finds itself in a period of dramatic economic crisis, with high unemployment figures, soaring state budget deficit, etc. From a bird's-eye view (as reflected in the Statistical Abstracts of Sweden), however, the development of Swedish society during the postwar period (1945–1990) has been characterized by the following trends:

•A relatively slow but steady growth of population (from seven to nine million people).

•An exodus from the countryside to townships and cities (from about 40 per cent to less than 20 per cent of the population living in the rural areas).

•A mobilization of the female labour force (from about 30 per cent to about 80 per cent in the labour force, the increase being concentrated in the public sector, especially local government employment).

•A reduction in the size of the households (one-person households increasing from some 20 per cent to some 40 per cent of all households).

•A gradual change from an industrial to a post-industrial society (in 1940 some 30 per cent, in 1990 some 70 per cent of the economically active population were active in services, communications and administration; the 50 per cent level was reached in the mid-1960s).

•A per capita GDP which grew considerably during the first decades after the Second World War, then grew at reduced speed, and during the last few years stagnated or even diminished but still is very high, in an international perspective: US$ 26,700 in 1990, as compared to 33,100 in Switzerland; 23,800 in Japan; 23,500 in former FRG; 21,400 in the USA; 17,000 in the UK, and 6,100 in Portugal (note that such figures, of course, are subject to changes in the rates of exchange – for instance, the turmoil in the international financial markets in the early 1990s).

•A sustained growth in public sector employment (in the 1970s, some 30 per cent of the economically active population, in the 1990s, some 40 per cent), especially in local government employment, which has been able to provide a relatively high level of social welfare to the Swedish population.

•An increasing economic dependence on the world surrounding Sweden, the value of the export as part of the gross domestic product at market prices increasing from about 20 per cent in the 1960s to about 25 per cent in the 1970s, culminating at some 30 per cent in the mid-1980s, and then vascillating around 25 per cent.

•A Social-Democrat dominance of the political system for most of the period, the bourgeois parties forming governments of their own only in the periods 1976–82 and from 1991 till the time of writing (1993).

Transportation and communication are important societal processes in a large, post-industrial society with a relatively large export, and a small, widely dispersed and mobile population living in small households with relatively weakened family ties. In all modernized countries mass media structures and mass media processes form vertical linkages between society's macro, meso and micro levels, horizontal linkages between different societal institutions, and external linkages to other societies (see Chapter 1). In Sweden – a country characterized by very high literacy, high levels of book and newspaper reading and a strong public service broadcasting system – these functions of the mass media are more important than in some other countries.

The legal framework regulating the basic conditions of the media are included in the Swedish constitution, which has medieval roots. It comprises the following constitutional laws: the Constitution proper, the Order of Succession, the Freedom of the Press Act, and the Freedom of Expression Act. The latter Act, of 1992, provides constitutional protection for electronic media according to the same basic principles as does the Freedom of the Press Act (originally stemming from 1766). These two constitutional laws offer not only freedom of expression, prohibition of censorship and freedom of the press and other media, but also far-reaching public access to documents sent and received by authorities and protection of source anonymity. Freedom of expression crimes are handled according to a jury system not otherwise found in Swedish law. Acquittals by these juries cannot be appealed against (Vallinder 1987).

The juridical framework outlined above is backed up by a partly official, partly semi-official system of specific media laws and agreements, ombudsmen and councils, which has been shown to have strong anchorage in professional ethics and public opinion (Weibull and Borjesson 1992).

There is a Radio Council, which is a governmental agency created retrospectively to overview the programmes distributed by public service radio and TV channels (more specifically, to monitor their agreement with the radio law and the official agreements with the programme companies), and to deal with complaints against such programmes raised by individuals. Its six members, including a professional jurist, are appointed by the government and are mostly recruited from politics and the mass media. Its verdicts have to be published by the offenders.

The semi-official part of the system includes an Ombudsman of the Press, and a Press Council chaired by a professional jurist. This is a joint venture founded and carried on by the three dominating professional associations in the area: the Publicists’ Club, the Swedish Union of Journalists, and the Swedish Association of Newspaper Publishers. Verdicts about editorial matters have to be published by the offenders.

With some variations, the other Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway) show considerable similarities in their media systems. Like Sweden, they are characterized by very high literacy, high levels of book and newspaper reading and a public service broadcasting system now finding itself in competition with commercial broadcasting. During the last few years, the media systems of all Nordic countries have been characterized by a process of radical structural change – a true sea change which no doubt will have consequences for a number of the societal subsystems discussed in Chapter 1 above. This change, of course, is global, and its essence is increasing globalization. It has often been more noticeable, however, in other parts of Europe and the rest of the world than in Sweden and other Nordic countries (see, for instance, Becker and Schonbach 1989; Blumler and Nossiter 1991; Hoffmann-Riem 1992; Kleinsteuber et al. 1986; Noam 1991). Behind it lie the computer, the satellite, the parabolic aerial, the cable and the VCR – all of which helped to turn a number of monopoly public service broadcasting systems into mixed systems governed partly by the political system, partly by the market. The diffusion of a number of electronic media within the Swedish population is shown in Figure 2.1.

Various aspects of the Swedish media system and its recent changes have been presented and discussed by a number of authors, including Carlsson (1986), Gustafsson (1986), Roe and Johnsson-Smaragdi (1987), Hulten (1988), Johnsson-Smaragdi (1989), Nowak (1991), Carlsson and Anshelm (1991, 1993), Weibull (1992) and Weibull and Anshelm (1992). In the Scandinavian countries, and not least in Sweden, because of the strength of the public service system,

Figure 2.1 Diffusion of TV and related media in the Swedish population aged 9–79, 1956–1992 (Source: SR/PUB, Stockholm and Carlsson & Anshelm(1993))

the change in the juridical framework necessitated by technological innovations came later than in many other countries. While these changes are far-reaching indeed, the most basic tendency characterizing the Swedish media scene during the last few decades is probably the large increase in the output of most media, as well as in the number of outlets and the size of their audiences, increases which for some media have been continuing since the end of the Second World War and which for electronic media have accelerated during the 1980s.

Here are some round figures about the growth in media output since the Second World War, borrowed from official statistics and special sources such as Carlsson and Anshelm (1991, 1993), Hadenius and Weibull (1993), Rosengren (1983) and Weibull (1992, 1993); and Weibull and Anshelm (1992):

•Books: from some 3,000 titles a year in the mid-1940s to some 12,000 in the early 1990s.

•Newspapers: from less than 3 million copies a day in 1945 to close to 5 million in the early 1990s.

•Radio (public service and private local radio): from some 60 hours broadcast a week in 1945 to some 450 hours in the early 1990s.

•Public service television: from some 10 hours a week in the mid-1950s to some 125 hours a week in the early 1990s.

Less expansive media include film and popular weekly magazines. Cinema film has experienced two serious threats: TV in the 1960s, and the VCR in the 1980s. In the former period two-thirds of all Swedish cinemas closed down; in the latter period, the number of films publicly shown in Sweden diminished from some 1,500 a year in the early 1980s to some 1,100 in the early 1990s. The total circulation of popular magazines is now somewhat below the 1945 level (some 2 million copies a week), after having oscillated around 4 million between 1955 and 1975. In relative terms, of course, this is a heavy reduction, because of the growth of the Swedish population. On the other hand there has been a considerable growth in magazines tailored to the interests of special readership groups (hobbies etc.).

Besides the basic tendency of increasing media output, some other important trends deserve mentioning (see Weibull and Anshelm 1992).

Firstly, Swedish media have experienced a process of increasing market control.

In terms of the ‘great wheel of culture in society’ (see Chapter 1), the economic and technological systems have more to say about the structure of the media system, while the normative, expressive and cognitive systems (religion and the polity, art and literature, science and scholarship) have experienced a corresponding decreasing influence. Newspapers are less closely tied to political parties and popular movements than previously. The great publishing houses have grown more market-oriented (witness, for instance, the many book clubs providing mainstream entertainment to a broad middle class) and less oriented towards a narrow cultural elite. Radio, once a great cultural, religious and political educator of national importance, to a large extent has become a medium for testing and launching hit music and/ or for local small talk and advertisements (see below). In the wings, commercial radio is waiting for its time to come.

In terms of the typology for reward systems presented in Chapter 1 (p. 18), this means that the mass media are moving well away from a semi-independent system towards a heterocultural system, a system characterized by increasing competition for audiences, leading up to demand or receiver control rather than supply or sender control. Obviously, this has consequences for the content offered by the media, for the diversity of this output, for the way that output relates to societal reality, as well as for the way it is assessed by professionals and by their audiences (see Rosengren et al. 1991).

Secondly and simultaneously, Swedish media have experienced a twin process of increasing localization and transnationalization.

Local and regional radio stations have increased in number, both inside and outside sthe public service system. The domestic content of one public service TV channel is produced outside the capital, Stockholm. In a similar but different vein, the position of the metropolitan press has been weakened in non-metropolitan areas, while the circulation of middle-sized local and regional newspapers has increased, as has the size of each issue.

In 1993, there were five Swedish TV channels reaching substantial portions of the Swedish audience: two licence-financed public service channels, one commercial public service channel, and two commercial channels. The former three are terrestrial, the latter two are distributed by satellite and cable. Only few and minor foreign TV channels have concentrated directly on a Swedish audience. Obviously, the foreign TV channels reaching Sweden by cable and satellite – commercial and public service channels alike – offer next to no Swedish content. Also the content of radio and television broadcasting in Sweden – be it public service or non-public service – to an increasing extent has foreign origins, mainly because music is such an increasingly dominating category of content in all radio, both broadcast and narrowcast.

In terms of the model in Figure 1.6, what this means, of course, is that the external influence on Swedish culture has grown increasingly strong during the last decade or so; very probably, it will continue to increase during years to come.

Thirdly, the trends with respect to concentration of ownership and control are somewhat divided.

The degree of media ownership concentration is high, but there are hardly any clear-cut tendencies. With respect to newspapers, the concentration has remained much the same during the last twenty-five years or so. The three biggest companies control some 40 per cent of the total circulation; the twelve biggest, some 75 per cent. For weeklies and magazines, the figures are somewhat higher, but declining (since the biggest group, Bonniers, has decided to gradually leave that market). It should be added that part of the daily press enjoys state subsidies. In overall terms these subsidies are small and declining (some 5 per cent of total press revenue in 1980, some 3 per cent in 1990), but they are vital to the existence of some newspapers. It is primarily Social Democrat and Centre party affiliated newspapers with powerful local competitors which enjoy subsidies, but also the leading Conservative newspaper, the Svenska Dagbladet, is subsidized. The subsidies are distributed according to strictly formal criteria related to readership rates in the place of publication. There is also strong legal protection against possible misuse of the state subsidies as a means of governmental control (see above). Similarly, although the most important fact about concentration in the Swedish media sector may be that the Bonnier family controls large portions not only of the newspaper market (some 20 per cent of the morning papers, some 50 per cent of the evening tabloids), but also of the markets for weeklies and comics (some 20 per cent and 50 per cent, respectively), cinema, movies (some 60 per cent) and books (some 30 per cent), it is also a fact that, by and large, the family has left the control of media content in the hands of their editors-in-chief.

When it comes to radio and television, the owner concentration was 100 per cent, of course, as long as there was a state monopoly. For radio, the monopoly was abolished, both de facto and dejure, in 1978, when voluntary organizations were granted the right to establish local, ‘neighbourhood’ radio stations. Fifteen years later, most radio content distributed is produced outside the public service system. In audience terms, however, the latter still dominates.

As satellite and cable techniques were introduced, the state monopoly of television was gradually abolished de facto, a process which started in the late 1970s, when cable systems were introduced. Today, some 40 per cent of Swedish households have access to satellite TV, as a rule by way of cable systems, most of which are owned by private or semi-private companies (the biggest being Telia, formerly a state agency, Swedish Telecom). De jure abolishment of the monopoly may be said to have occurred in 1989, when it was decided that a private company should be granted the licence for the third terrestrial Swedish TV channel (although the company was selected only in 1991). However, there is still a remnant of the monopoly, since the formal right to decide on terrestrial TV distribution licensing continues to rest with the government.

All in all it may be maintained, then, that the concentration of private ownership control of Swedish print media is high and stable, while the public ownership control of the electronic media distributed in Sweden is high and declining. The total output of electronic media has increased considerably during the post-war period; among the print media, books and newspapers have also increased considerably, while the output of weeklies has declined or stagnated, as has film output. These structural conditions are reflected, of course, at the micro level: the individual consumption of mass media.

In terms of daily exposure, television, radio and the morning newspaper top the media league: on an average day, between 70 and 80 per cent of the population aged between 9 and 79 expose themselves to each of these media – radio and TV having the edge before the morning newspaper. In terms of time devoted to the media, radio used to be a clear leader (a couple of hours a day, dominated by popular music and news stories), followed by TV (some two hours). The recently immensely increased TV output has put TV viewing more on a par with radio (also in the sense of having become a moving wallpaper), but it may be too early to give any precise figures here. (The situation is complicated also by the VCR, available to some 60 per cent of the population, but on an average day used only by 5–10 per cent.) Readers of morning papers spend some 30 minutes reading their daily (usually a subscribed local paper), and so do the third of the population who are readers of the often rather sensational afternoon tabloids. On an average day, one-third of the population reads a book, and they report it takes them an hour or so. Weeklies are read by some 20 per cent of the population, especially by middle-aged women.

By and large it could be said that while the recent structural changes briefly presented in this chapter may have been rather far-reaching, their effects on overall individual media use have so far been fairly modest. This is seen most strikingly in the fact that the immense increase in television output which during the last decade or so has been made available to Swedes has not (yet) resulted in any corresponding increase in actual viewing. Among small children, there was actually a decrease in viewing during the 1970s and 1980s, and so far this decrease has not been replaced by any marked increase (see Schyller 1989, 1992). Among special segments of the population, of course, the increased output may have had its effects – for instance among adolescents and young adults (see Chapter 4). Across the board, though, the impact is rather modest.

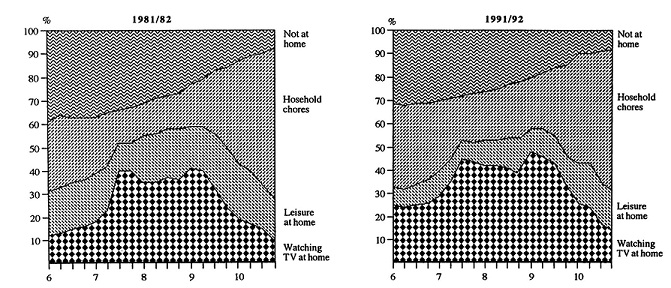

Even modest changes have consequences, however. This is illustrated in Figure 2.2 (borrowed from Cronholm et al. 1993). In terms of three types of activities (household chores, TV viewing, and other home-based leisure activities), the figure shows what Swedes aged 9–79 did at home on an average weekday evening in the years 1981/82 and 1991/92, respectively. It will be seen that in the early 1990s, more Swedes spent their evening time at home than during the 1980s, and that a larger portion of them them spent their time on household chores. The portion of the population who spend their time TV viewing has indeed increased somewhat, at the expense of other homebound leisure activites, which have been drastically reduced, in relative terms at least.

Even a rather modest increase in TV viewing, then, may actually have potentially important consequences. In the rest of this book we will have ample opportunities to reflect upon such relationships between media use and other activities, especially among young people. Chapter 3 will present the research programme behind the book, a programme within which we have been collecting a massive body of data on young people's media use, and its causes and consequences, during the period of dramatic structural change just outlined.

REFERENCES

Becker, L. and Schönbach, K. (eds) (1989) Audience Responses to Media Diversification. Coping With Plenty, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Blumler, J. and Nossiter, J. (eds) (1991) Handbook of Comparative Broadcasting, London: Sage.

Carlsson, U. (ed.) (1986) Media in Transition, Göteborg: NORDICOM.

Carlsson, U. and Anshelm, M. (eds) (1991) Medie-Sverige ‘91, Göteborg: NORDICOM.

–– (1993) Medie-Sverige 1993,Göteborg: NORDICOM.

Cronholm, M., Nowak, L., Höijer, B., Abrahamsson, U.B., Rydin, I., and Schyller, I. (1993) ‘I allmanhetens tjänst’, in U.Carlsson. and M.Anshelm (eds) (1993) Medie-Sverige 1993, Göteborg: NORDICOM.

Gustafsson, K.E. (1986) ‘Sweden’, in H.J.Kleinsteuber, D.McQuail and K.Siune (eds) Electronic Media and Politics in Western Europe, Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Hadenius, S. (1990) Swedish Politics during the 20th Century, Stockholm: Swedish Institute.

Figure 2.2 Weekday home activities in the Swedish population aged 9–79, 1981/82 and 1991/92, 6–10.45 pm (Source: SR/PUB and Carlsson & Anshelm (1993))

Hadenius, S. and Lindgren, A. (1992) On Sweden (2nd edn), Stockholm: Swedish Institute.

Hadenius, S. and Weibull, L. (1993) Massmedier. En bok om press, radio och TV, Stockholm: Bonnier Alba.

Hoffmann-Riem (1992) ‘A special issue: Media and the law. The changing landscape of Western Europe’, European Journal of Communication 7: 147–302.

Hultén, O. (1988) ‘Sweden’, in M.Alvaro (ed.) Video World Wide – An International Study, Paris: Unesco.

Johnsson-Smaragdi, U. (1989) ‘Sweden: Opening the doors – cautiously’, in L.Becker and K.Schönbach (eds) Audience Responses to Media Diversification. Coping With Plenty, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Kleinsteuber, H.J., McQuail, D. and Siune, K. (eds) (1986) Electronic Media and Politics in Western Europe, Frankfurt am Main: Campus.

Noam, E. (1991) Television in Europe, New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nowak, K. (1991) ‘Television in Sweden 1991’, in J.Blumler and J.Nossiter (eds) Handbook of Comparative Broadcasting, London: Sage.

Roe, K. and Johnsson-Smaragdi, U. (1987) ‘The Swedish “mediascape” in the 1980's European Journal of Communication 2: 357–370.

Rosengren, K.E. (1983) The Climate of Literature, Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Rosengren, K.E, Carlsson, M. and Tågerud Y. (1991) ‘Quality in Programming: Views from the North’, Studies of Broadcasting 27: 21–80.

Schyller, I. (1989) ‘Barn och ungdom tittar på svensk tv’, in C.Feilitzen, L.Filipson, I.Rydin and I.Schyller (eds) Barn och unga i medieåldern, Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren.

–– (1992) ‘TV-tittandet 1991 bland barn och ungdomar 3–24 år’ PUB, 9.

Vallinder, T. (1987) ‘The Swedish jury system in press cases: An offspring of the English trial jury?’, The Journal of Legal History 8 (2): 190–220.

Weibull, L. (1992) ‘The status of the daily newspaper. What readership research tells us about the role of newspapers in the mass media system’, Poetics 21:259–282.

–– (1993) ‘Sweden’, in J.Mitchell, and J.Blumler (eds) Television and the Viewer Interests, Düsseldorf: The European Institute of the Media.

Weibull, L. and Anshelm, M. (1992) ‘Indications of change. Developments in Swedish media 1980–1990’, Gazette 49: 41–73.

Weibull, L. and Börjesson, B. (1992) ‘The Swedish media accountability system: A research perspective’, European Journal of Communication 7: 121–139.