Project Management

Abstract

This chapter defines project management and project manager and discusses the skills a project manager should possess. It also explains the purpose and basic clauses of a project charter, as well as the function of a project office.

Keywords

Project management; project manager; project charter; project office

Chapter Outline

It is obvious that project management is not new. Noah must have managed one of the earliest recorded projects in the Bible – the building of the ark. He may not have completed it to budget, but he certainly had to finish it by a specified time – before the flood — and it must have met his performance criteria, as it successfully accommodated a pair of all the animals.

There are many published definitions of project management, (see BS 6079 and ISO 21500), but the following definition covers all the important ingredients:

The planning, monitoring, and control of all aspects of a project and the motivation of all those involved in it, in order to achieve the project objectives within agreed criteria of time, cost, and performance.

While this definition includes the fundamental criteria of time, cost, and performance, the operative word, as far as the management aspect is concerned, is motivation. A project will not be successful unless all (or at least most) of the participants are not only competent but also motivated to produce a satisfactory outcome.

To achieve this, a number of methods, procedures, and techniques have been developed, which, together with the general management and people skills, enable the project manager to meet the set criteria of time cost and performance/quality in the most effective way.

Many textbooks divide the skills required in project management into hard skills (or topics) and soft skills. This division is not exact and some are clearly interdependent. Furthermore it depends on the type of organization, type and size of project, and authority given to a project manager, and which of the listed topics are in his or her remit for a particular project. For example, in many large construction companies, the project manager is not permitted to get involved in industrial (site) disputes as these are more effectively resolved by specialist industrial relations managers who are conversant with the current labour laws, national or local labour agreements, and site conditions.

The hard skills cover such subjects as business case, cost control, change management, project life cycles, work breakdown structures, project organization, network analysis, earned value analysis, risk management, quality management, estimating, tender analysis, and procurement.

The soft topics include health and safety, stakeholder analysis, team building, leadership, communications, information management, negotiation, conflict management, dispute resolutions, value management, configuration management, financial management, marketing and sales, and law.

A quick inspection of the two types of topics shows that the hard subjects are largely only required for managing projects, while the soft ones can be classified as general management and are more or less necessary for any type of business operation whether running a design office, factory, retail outlet, financial services institution, charity, public service organization, national or local government, or virtually any type of commercial undertaking.

A number of organisations, such as APM, PMI, ISO, OGC, and licencees of PRINCE (Project In a Controlled Environment) have recommended and advanced their own methodology for project management, but by and large the differences are on emphasis or sequence of certain topics. For example, PRINCE requires the resources to be determined before the commencement of the time scheduling and the establishment of the completion date, while in the construction industry the completion date or schedule is often stipulated by the customer and the contractor has to provide (or recruit) whatever resources (labour, plant, equipment, or finance) are necessary to meet the specified objectives and complete the project on time.

Project Manager

A project manager may be defined as:

“The individual or body with authority, accountability and responsibility for managing a project to achieve specific objectives” (BS 6079-2:2000)

Few organizations will have problems with the above definition, but unfortunately in many instances, while the responsibility and accountability are vested in the project manager, the authority given to him or her is either severely restricted or non-existent. The reasons for this may be a reluctance of a department (usually one responsible for the accounts) to relinquish financial control, or it is perceived that the project manager has not sufficient experience to handle certain tasks such as control of expenditure. There may indeed be good reasons for these restrictions which depend on the size and type of project, the size and type of the organization, and of course the personality and experience of the project manager, but if the project manager is supposed to be in effect the managing director of the project (as one large construction organisation liked to put it), he or she must have control over costs and expenditure, albeit within specified and agreed limits.

Apart from the conventional responsibilities for time, cost, and performance/quality, the project manager must ensure that all the safety requirements and safety procedures are complied with. For this reason the word safety has been inserted into the project management triangle to reflect the importance of ensuring the many important health and safety requirements are met. Serious accidents not only have personal tragic consequences, but they also can destroy a project or indeed a business overnight. Lack of attention to safety is just bad business, as any oil company, airline, bus, or railroad company can confirm.

Project Manager’s Charter

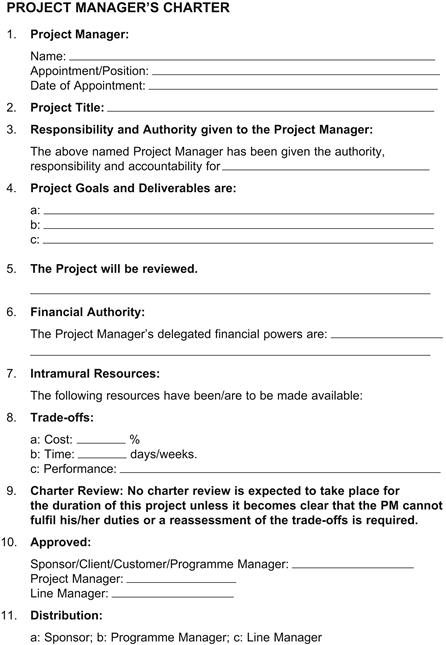

Because the terms of engagement of a project manager are sometimes difficult to define in a few words, some organizations issue a project manager’s charter, which sets out the responsibilities and limits of authority of the project manager. This makes it clear to the project manager what his or her areas of accountability are, and if this document is included in the project management plan, all stakeholders will be fully aware of the role the project manager will have in this particular project.

The project manager’s charter is project specific and will have to be amended for every manager as well as the type, size, complexity, or importance of a project (see Figure 2.1).

Project Office

On large projects, the project manager will have to be supported either by one or more assistant project managers (one of whom can act as deputy) or a specially created project office. The main duties of such a project office is to establish a uniform organisational approach for systems, processes, and procedures, carry out the relevant configuration management functions, disseminate project instructions and other information, and collect, retrieve, or chase information required by the project manager on a regular or ad hoc basis. Such an office can assist greatly in the seamless integration of all the project systems and would also prepare programs, schedules, progress reports, cost analyses, quality reports, and a host of other useful tasks that would otherwise have to be carried out by the project manager himself. In addition the project office can also be required to service the requirements of a programme or portfolio manager, in which case it will probably have its own office manager responsible for the onerous task of satisfying the different and often conflicting priorities set by the various projects managers. (See also Chapter 10.)