4. Make Green Strategy Actionable with a Proven Approach

4.1. Use Leading Practices for Making Strategic Visions Actionable

Businesses can effectively apply well-established methodologies for making business-driven operational improvements to areas of environmental stewardship. Such methodologies for implementing strategy or reaching strategic objectives in an organization often provide a clear way to trace the initiatives and programs back to the original vision and high-level objectives. Companies simply need to trace the initiatives in which investments are made back to the driving strategic imperatives. This traceability is important to maintain because it offers several significant benefits at relatively little cost.

First, creating initiatives and programs from a driving strategic vision with explicit traceability between the two ensures that the business transformation activities actually align with and support the strategic vision. Businesses often find that functional areas, such as IT departments, product development groups, sales and marketing groups, or customer service teams, launch their own improvement initiatives that align poorly with the business strategy. This can result in technology initiatives that don’t meet business needs, products that don’t meet consumer needs, marketing programs that don’t support global brands, or difficulty portraying a “single face” to customers. Traceability weeds out pet projects and low-value investments that don’t enable the business strategy.

Second, traceability between a high-level strategic vision and the initiatives that implement the vision enables businesses to incorporate changes and revise action plans when the vision or business priorities change. This is especially important in the area of environmental stewardship, in which high-level objectives can change due to technology breakthroughs, new legislation, or changes in the price trends of fuel and scarce raw materials. Businesses might launch some transformation initiatives proactively, based on future-state scenarios whose likelihood is uncertain. As trends change and predicted scenarios become more or less likely to occur, traceability back to the driving business strategy and strategic imperatives is crucial.

For example, new legislation might require an enterprise to change a greenhouse gas emissions–reduction target from 20 percent to 30 percent. Traceability enables an organization to quickly identify which existing initiatives and programs support such an aggressive goal.

Third, as the business environment changes, a company can use traceability to reprioritize its portfolio of projects, to keep investments aligned with the strategic direction. For example, if funding availability for an initiative changes, the organization could rapidly prioritize by tracing the initiative back to its strategic drivers and identifying its benefits and costs.

Fourth, from a change-management perspective, the importance of transformation initiatives and larger programs is frequently easier to communicate when their contribution to a strategic vision is clear.

Figure 4.1 depicts one methodology that businesses can use to develop and follow an action plan that implements a green strategy. Although Figure 4.1 implies that this methodology is sequential, it should actually be treated as iterative: Knowledge and insight gained from any step could influence content developed in one or more previous steps.

Figure 4.1 Green strategy implementation methodology

We next describe this methodology and then focus on a case study of a company whose current state includes few leading practices for environmental stewardship.

4.2. Formulate Green Strategic Vision and Imperatives

In Step 1 of the methodology, an enterprise formulates a strategic vision that describes its high-level objectives.

The green strategic vision is often guided by assessments against maturity models, reviews of benchmarks and leading practices from other companies and other industries, industry and global trends, analyses of market and customer segmentation, evaluations of new technology, and assessments of organizational core competencies. A company often communicates a strategic vision to its employees to facilitate organizational alignment and focus business activity toward key objectives in a uniform way.

However, because strategic visions are often articulated at too high of a level to be actionable, businesses must construct strategic imperatives so that the leadership of each business function can formulate plans to take specific action. Strategic imperatives align closely with the higher-level vision, but they also have a higher degree of clarity, to help drive the development of new business capabilities.

Consider an example of a company whose current state includes few leading practices for environmental stewardship. Although this is a hypothetical case, to illustrate the methodology and its application, its challenges and opportunities available are similar to those faced by thousands of companies around the world. As with many companies, this one has established offices and manufacturing facilities in the Americas and Europe, and plans to construct similar facilities in high-growth markets in Asia. This company has also recently completed a maturity assessment, benchmarking analysis, and customer segmentation assessment to compare itself to its key competitors and better understand its customers. The findings indicate that although no clear industry leader currently exists for environmental stewardship, competitors are actively working to establish an early-mover position by investing in product development and implementing sustainable-energy practices at some facilities. Customers across all segments now prefer products that are environmentally friendly, which represents a significant change in their behavior. Finally, through executive-visioning sessions, senior leadership has decided to add environmental stewardship to the company’s strategic agenda and make certain investments to establish a leadership position in its industry.

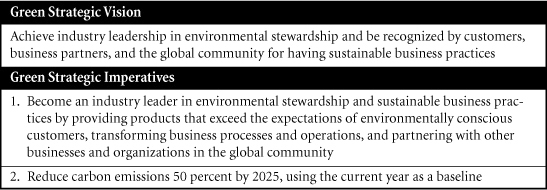

Companies that fit the profile of our sample company could formulate a sensible strategic vision and associated strategic imperatives such as the ones shown in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Example of Green Strategic Vision and Associated Strategic Imperatives

The strategic vision addresses the most important issues to this company from an environmental-stewardship perspective. These include responding to changing customer preferences and establishing a competitive position in the industry. The lower-level, more actionable strategic imperatives address how the organization will achieve that vision, through changes to product offerings, facilities, and partnerships.

4.3. Determine Enabling Green Business Capabilities

In Step 2 of the methodology, companies determine enabling green business capabilities that focus on areas of the business that require new development to achieve the vision.

Companies can develop green business capabilities with relatively broad participation from senior leaders and managers because their knowledge of existing capabilities, and their understanding of the feasibility for developing new ones, is often helpful. This step is important because, without the capability-level detail, organizations won’t have enough information for all the different business functions to define and launch the appropriate transformation initiatives. Traceability is maintained at this step because the capabilities remain tied to the strategic vision through their associated imperatives. After these green business capabilities are determined, it’s much easier for leaders and managers to envision the level of transformation that will be required in their area of the business.

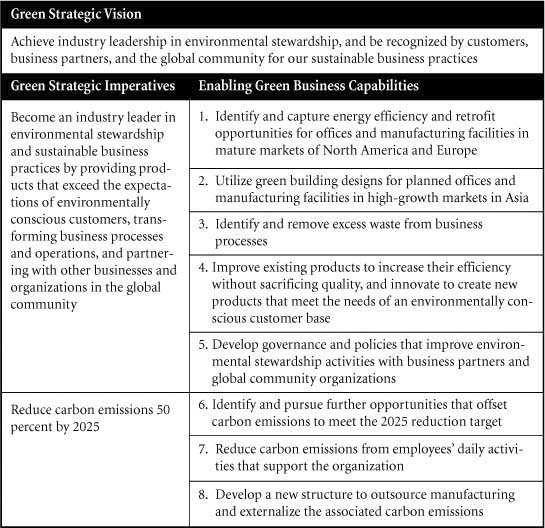

Now consider the case study and its two green strategic imperatives identified in Table 4.1. Table 4.2 summarizes a sensible set of enabling green business capabilities that are required to meet the strategic imperatives, and also shows how traceability is maintained as lower levels of detail are established.

Table 4.2 Example of Enabling Green Business Capabilities and Traceability

The company can directly trace back the two sets of green business capabilities (items 1–8) to their associated green strategic imperatives. If either the vision or the imperatives change because of a shift in business priorities, the company will immediately know the implications to the enabling capabilities. The level of detail is still not exhaustive enough to require deep subject-matter expertise, nor is it sufficient to begin quantifying detailed benefits, costs, and environmental impact improvements. Also note that part of the first strategic imperative, particularly business capability 4, is strongly aligned with revenue-growth priorities.

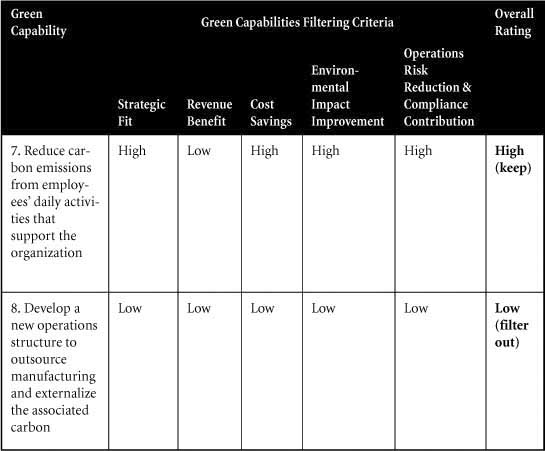

However, the capabilities are described in sufficient detail that an organization can coarsely filter some of them out, if appropriate, to eliminate unnecessary work when constructing the action plan in subsequent steps. Although an organization would usually filter across all the green business capabilities—and potentially even across every capability that supports an action plan for all business visions (green and other), when green strategy and business strategy planning are integrated—we illustrate the approach for only the last two capabilities from Table 4.2. Table 4.3 summarizes the filtering results for these two capabilities.

Table 4.3 Framework to Filter and Eliminate Low-Value Green Capabilities

For these two capabilities, the company clearly should further explore the first one, capability 7, but it can filter out the second one, capability 8, and lose little value toward environmental stewardship. Although the filtering criteria can be customized for an individual business, the following analysis of capability 7 from Table 4.3 helps to more clearly define the criteria used here:

• A high strategic fit indicates that the capability aligns well with the driving strategic imperative and vision, which is easily established because traceability is preserved.

• A low revenue benefit indicates that the company should not anticipate a significant positive effect on revenue or revenue growth simply by having employees telecommute more often.

• A high cost savings indicates that a connection between increased telecommuting and reduced office facility costs is possible. For example, if 20 percent of the workforce is telecommuting at any particular time, the company could reduce office space or operate existing office space more economically with fewer people.

• A high environmental impact improvement indicates that the carbon emissions reductions from having an effective telecommuting program in place are significant.

• A high operations risk reduction and compliance contribution indicates that having this capability actually reduces the normal risk from daily operations, and also reduces the potential risk associated with future regulatory compliance for carbon emissions.

For green business capability 8 in Table 4.3, simply externalizing carbon emissions without the ability to demonstrate lower net emissions in the lifecycle chain could result in customer backlash if the transformation is positioned as one that improves environmental stewardship. However, if the company had a more traditional business imperative to transform fixed costs into variable costs, it might not filter out capability 8 at this step because of priorities other than environmental stewardship.

In practice, the decision to filter out capabilities at this step is not always clear, especially for capabilities that might have an overall rating of medium. Companies should avoid filtering out borderline capabilities at this early step because another filter, based on more detailed analysis, will be applied when potential initiatives are prioritized in Step 5. It’s also important to consider prerequisite and interdependent capabilities when applying this framework. For example, a capability that has an overall rating of low might actually be a prerequisite for another capability, in which case it shouldn’t be eliminated here. In a later step, one combined initiative might target those two capabilities together.

4.4. Establish Future-State Organization, Process, and Technology Needs

In Step 3 of the methodology, the organization establishes specific needs that will meet the objectives of the strategic vision.

The business establishes future-state needs to collectively cover what is required to fulfill the strategic imperatives. The organization, process, and technology needs to show business leaders, managers, and practitioners what will change and what will be new to the business at a deeper level of detail. Throughout every step of the methodology, traceability is maintained. In this step, each need ties back to its associated green business capability.

An organization could establish similar needs to support different capabilities. For example, the need for employees to conduct energy audits might support two different capabilities, such as one for capturing facility-retrofit opportunities (capability 1 in Table 4.2) and another for removing excess waste from business processes (capability 3 in Table 4.2). In later steps, an organization can combine these similar needs in such a way that they are met by the same initiative or as part of the same program of initiatives.

In this step, a business can map the future-state needs to any business model or business architecture, to analyze the areas that require change, how much transformation to expect, and what kind of transformation to anticipate in each business area—organization, process, or technology change.

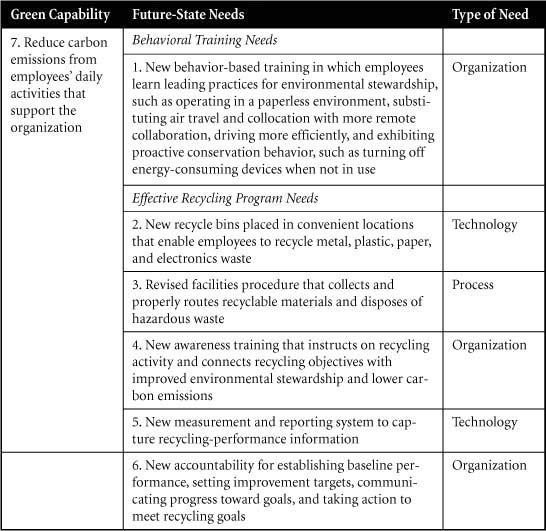

Now consider the example in which one green business capability, capability 7, is passed through the filtering criteria in the previous step for further analysis. This example doesn’t analyze the other green capabilities (1–6)because it’s intended to only illustrate the methodology, not to provide a full implementation plan. Table 4.4 shows example future-state needs associated with green business capability 7.

Table 4.4 Example of Future-State Needs and Traceability

Note that a deeper level of detail is provided in describing what must change. This gives functional leaders in a business a clear picture of what will be different in the end state, and they can even infer who should be involved to achieve the transformation.

Although a one-to-one relationship exists in this example between each need and its type, needs don’t have to fall into just one category type. In practice, needs commonly require more than just one type of transformation; some require all of them—organization, process, and technology. Assigning a type of need here gives an indication of whether the transformation will be balanced or heavily biased toward technology, process, or organizational change.

At this point, the methodology has answered why transformation is needed from the driving strategic vision and associated imperatives, and what must change from the capabilities and associated needs. The next step identifies how the business must change to implement green strategy.

4.5. Describe Current State and Assess Gaps with Future State

In Step 4 of the methodology, the organization assesses the gaps associated with each need. Larger gaps require a higher degree of transformation to fill.

With an understanding of why change is needed and what must change, the organization performs a gap assessment to understand how the transformation can occur, how much change is actually needed, and what kind of transformation should take place. This is the final step before defining transformation initiatives to fill gaps that meet the objectives of a strategic vision. Again, traceability is preserved to clearly document how filling the gaps will contribute to meeting the original strategic vision.

For most gap assessments, the gaps themselves are sometimes not written explicitly if the current state and future state are sufficiently described. A gap is simply the difference between the current and future states. Similar to Step 3, an organization can assign gaps a type, depending on whether an organization, process, or technology transformation resolves them. However, unlike in the previous step, gaps usually fall into one type. By defining gaps in this way, an organization can easily combine them into natural groups. Natural groups can be a collection of gaps from any number of future-state needs that arise from any of the green business capabilities. The groups enable an organization to form initiatives that minimize duplication of effort and enable one initiative to potentially meet the needs of several strategic imperatives and many enabling capabilities.

An organization can assess all the gaps, along with their associated needs, to determine their importance in building the required capabilities. An organization can also assess whether they are required in the near term or whether they can be developed over a longer time period for more flexibility during implementation.

Leaders can assess organization gaps for their complexity, level of cultural change required, number of people in the organization affected, and fit with existing knowledge and skills.

An organization can assess process gaps for their complexity, level of process change required, and amount of new training needed.

Leaders can also assess technology gaps for the complexity of features and functionality, interoperability requirements, scalability requirements, and reliability expectations.

At this step in the methodology, the gap assessment details will add clarity to the initiatives defined in the next step, which fill the gaps. The last activity in this step is to identify an initiative title that will fill the gap. Initiatives titles in this step are closely aligned with the natural groups discussed earlier.

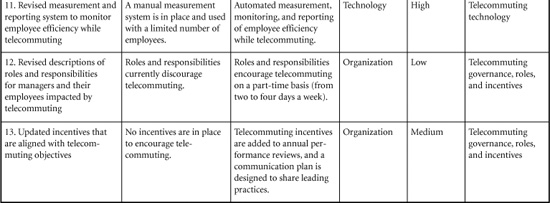

Turning again to the example, and focusing only on the telecommuting program needs (8–13) to illustrate the approach, Table 4.5 describes a set of corresponding gaps, along with traceability back to the future-state needs.

Table 4.5 Example of Gap Assessment and Traceability

Gap assessments require detailed knowledge of the current state of the business, along with reasonably accurate knowledge of what the future state of the business will look like after the needs have been met. However, complete knowledge of the future state isn’t always necessary at this step because an organization could defer additional depth of subject-matter expertise or time required to achieve a deeper level of detail until the initiative itself is funded, staffed, and launched.

In this example, the same initiative will fill multiple gaps. In an actual application of this methodology, a lesser number of initiatives might fill hundreds of gaps. Furthermore, in an actual application, an organization might want to assess the gap sizes in more detail. Experienced project managers can often judge the size of a gap and the level of effort anticipated to fill a gap, in terms of both investment and resources required based on previous knowledge of similar projects. One advantage from quantifying the size of each gap in terms of costs and resources in this step is that it simplifies the work of the next step to determine the cost of an initiative that fills multiple gaps.

4.6. Define and Prioritize Transformation Initiatives

In Step 5 of the methodology, the organization defines the initiatives that fill the gaps assessed in the previous step.

The gaps were associated with natural groups that a single initiative could fill. In this step, the organization clearly articulates and documents the initiatives, estimates implementation costs, and benefits, and then prioritizes them.

Documenting each initiative entails identifying an owner, describing the initiative, and articulating the current and future state using details from the gap assessment. The solution that meets the objectives of an initiative and fills the associated gaps can be organizational, technological, process-oriented, or a combination of the three.

Initiative definitions also include information on alternate approaches for filling the gaps between the current and future states. Timing considerations that describe whether the opportunity should be considered a short-term quick hit or longer-term improvement are also captured, along with other timing considerations, such as estimated implementation duration.

Finally, initiative definitions include qualitative and quantitative costs and benefits, along with the criteria that will be used to prioritize all the initiatives.

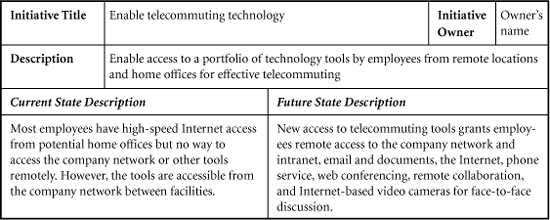

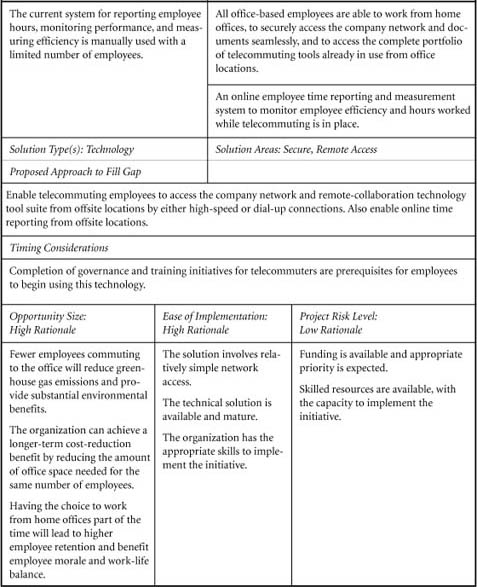

Table 4.6 is a sample initiative-definition template for the telecommuting initiative from the case study.

Table 4.6 Example Initiative-Definition Template Completed for One Initiative

The opportunity size should relate to the prioritization criteria associated with benefits (strategic fit, revenue benefit, cost savings, environmental impact improvement, and operations risk reduction and compliance contribution). These criteria should be well correlated to how their corresponding capabilities were rated for the same dimensions in a previous step. Ease of implementation, partly determined by implementation cost and the implementation resources needed and their availability, is high when the implementation isn’t expected to be difficult. The low project-risk level indicates that organizational readiness is good, executives and managers are supportive, and priority for implementation resources and funding is high.

Other prioritization criteria to consider include the complexity of the initiative, the duration of the project and time to benefit, interdependencies with other initiatives, and potential options that the initiative provides for making follow-up improvements. At this step, it’s possible to gather enough detail to make appropriate assumptions and calculate the net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), or return on investment (ROI) for each initiative.

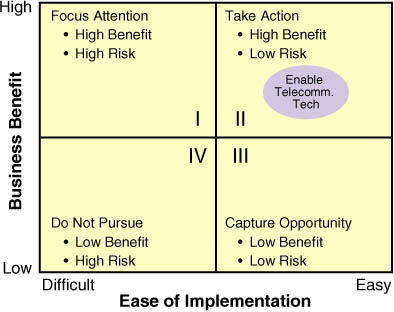

With the elaborate planning environments in many businesses today, seldom does initiative prioritization, or project portfolio planning, result in a one-dimensional prioritized list of initiatives, with the ones below a certain score being cut from the plan. Figure 4.2 depicts a common prioritization framework and illustrates where the initiative described in Table 4.6 is positioned.

Figure 4.2 Prioritization framework

Initiatives that fall into Zones II and III typically make sense to launch and implement, but those in Zone I require additional focus to determine whether they should be pursued. Initiatives in Zone I often are assigned a later start date on the transformation roadmap, to allow more time for additional investigation and to raise the ease of implementation. Initiatives in Zone IV don’t provide sufficient benefits, and the implementation difficulty is disproportionately high; those factors don’t warrant making an implementation investment. In some cases, especially when business benefits depend on capturing market share and achieving revenue growth in a competitive environment, the implementation timing of an initiative can be the “critical path” to achieving projected results.

Now that a set of transformation initiatives has been defined with explicit traceability back to the strategic vision that they support, the next step is to establish a transformation roadmap.

4.7. Establish Transformation Roadmap and Future-State Blueprint

In Step 6 of this methodology, an organization creates a transformation roadmap and future-state blueprint to effectively manage the strategic vision implementation.

The organization has defined and prioritized the initiatives, quantified their costs and benefits, and defined the resources required to implement them. The transformation roadmap established in this step includes all the initiatives to be implemented and their timing, with approximate start and end dates, and considers interdependencies and constraints across initiatives. For example, if the capabilities enabled by one initiative are a prerequisite for beginning another initiative, the roadmap reflects this timing constraint for those two initiatives. Other typical constraints include funding limitations and scarcity of qualified resources.

Until this step is complete, the final portfolio of initiatives to be implemented is unknown. An organization should explore different roadmap alternatives before selecting the final one. Frequently considered roadmap alternatives include one in which spending is somewhat unconstrained and most initiatives are implemented, one with balanced investment in which low-priority initiatives are dropped, and one with limited investment in which even some high-value initiatives might be eliminated. Other dimensions to explore, in addition to investment and implementation cost, include the rate of value realized (quickly versus spread over a longer period of time), the business and technology risk level, and the amount of focus given to enterprise-level initiatives versus ones that benefit only a few business units. Comparing different alternatives across these dimensions makes clear which initiatives and associated benefits need to be dropped or delayed to meet the imposed constraints. Because complete traceability is still in place from each initiative back to the green strategy that they are intended to implement, it’s also clear which aspects of the strategic vision must be compromised in different roadmap alternatives.

Although the time horizon of a transformation roadmap can extend five years or more, the initiatives associated with the telecommuting example from the case study can be implemented in one year. The roadmap for the case study, in Figure 4.3, reflects the timing of initiatives for the whole telecommuting program, and shows where initiatives might run concurrently to more rapidly achieve the overall objective.

Figure 4.3 Transformation roadmap for telecommuting program

Some companies end their strategic-planning activity when they produce a final portfolio of initiatives and complete the transformation roadmap. However, the leading practice is to also establish the future-state blueprint so that a clear picture of the end state is created after all the initiatives are complete. A full blueprint includes a view of the end-state organization and the important changes, the end-state processes and how they will have changed, and the end-state information technology architecture and how it will have changed. These elements collectively represent a holistic view of the future-state business architecture.

Methods for articulating a holistic view of business architecture vary widely across different enterprises, depending on the level of complexity in the business and its operations. For example, some companies operate with decentralized technology functions without a complete view of their disparate systems, interfaces, and decentralized data. Other companies have clearly documented their applications, interfaces, data, and ownership governance so that identifying changes to the system architecture at an enterprise level is more straightforward. Similarly, companies with a relatively advanced business process management (BPM) structure in place typically have a straightforward task to articulate the future-state blueprint from a process perspective.

4.8. Manage Transformation, Measure Performance, and Sustain Improvements

The leading practices for transformation and change management apply to a green portfolio of initiatives in the same way they apply to most other business areas. Companies must manage the following activities:

• Project activities, for high-quality outcomes

• Staff and infrastructure, for high performance

• Scope and timeline, for cost-effectiveness

• Stakeholder relationships, for ongoing commitment

• Risks and mitigation options for smooth implementation

It’s also important to verify that environmental, business, and organization benefits are realized as different projects are completed. Especially for quantified benefits, companies should establish a measurement and reporting system, measure baseline performance, set improvement targets, and monitor changes to the baseline to determine whether improvement targets are achieved. Where expected improvements don’t materialize, the organization must analyze root causes and implement corrective actions.

For larger, complex programs that need to manage transformation efforts across business units or divisions, leading practices often call for a centralized program management organization (PMO) to manage multiple initiatives across different programs. A PMO can operate across initiatives to plan and monitor activities, communicate and report all aspects of transformation, manage and resolve escalated issues, and control changes to scope. The same PMO can manage contracts, finances, resources, documents, infrastructure, quality, and risk. An effective PMO can also manage and report benefits as they are demonstrated, and collect and communicate knowledge and lessons learned across initiatives.

Inevitably, new ideas for initiatives will spring from innovative thinking by all stakeholders, even after the initial transformation roadmap is developed. To respond to these new opportunities, an enterprise should have a streamlined process to evaluate new ideas and draft initiatives, prioritize them with the existing portfolio of initiatives, and place them on the transformation roadmap when applicable.

4.9. Refresh at Regular Intervals

Assuming that a transformation roadmap spans five years, the equivalent of at least one year should be refreshed annually. Even if the strategic vision and imperatives have not changed, some initiatives will be complete with their benefits in place, and the organization can define a new fifth year of activity. Changes to the strategic vision and imperatives, economic expansion or contraction, new legislative activity, changes in the competitive landscape, and availability of new technology and leading practices are additional reasons to refresh the transformation plan.

Refreshing the plan annually is most common, and it’s usually coordinated with other business planning activities so that the organization can address interdependencies between initiatives for green strategy and other business initiatives.

Returning to our case study, consider the original set of enabling green business capabilities from Table 4.2. Capabilities 5 and 7—developing governance and policies for working with business partners, and enabling employees to proactively reduce their own carbon emissions—would likely gain significant traction and might be fully implemented in the first year of the transformation roadmap.

Capabilities 1, 3, and 4—retrofitting offices and manufacturing facilities, removing excess waste from business processes, and improving existing products—might start in the first year, but will likely extend into the second, third, and even fourth years of the roadmap. The timing of product-based benefits will depend on the length of the product development cycle, which varies widely across different industries.

Capabilities 2 and 6—constructing green facilities and identifying carbon emission–offset opportunities—will potentially be pursued vigorously in the second through fifth years of the transformation roadmap as the business grows into new markets and identifies new opportunities to meet the 2025 target. Capability 8 was eliminated, as too low-value, early in the process.

Chapter 6, “Applying Green Sigma to Optimize Carbon Emissions,” describes an actual case in which facility improvements are made using the Green Sigma methodology and its technology toolset. The initiative described by that case is similar to the kind that would be expected from the enabling green capability that improves the efficiency of facilities.

4.10. Ten Critical Success Factors for Transformation

Analysts have identified the ten most critical success factors of initiatives that support environmental stewardship.

First, committed leadership is essential for achieving successful transformation in environmental stewardship. Unlike other business initiatives, those linked to a green strategy are always at risk of taking a back seat to other activities whose connection to traditional business performance is clearer. When leadership is visibly supportive and takes action to demonstrate commitment, the risk is mitigated. Expanding on the telecommuting illustration described earlier, committed leadership sponsors and commits to making appropriate investments, communicates the importance of the program for business and environmental benefits, and even participates in the program to reinforce the behavior in their employees. For environmental stewardship, commitment from leadership often must come from many different levels within the organization, not simply from executive management. For example, facilities managers are essential leaders who must be committed whenever a transformation initiative involves buildings and other facilities.

Second, establishing and maintaining a clear focus on the environment is an important factor for successful transformation. Just as a clear focus on the customer is needed for other business-driven initiatives, a focus on the environment ensures that affected processes are created from an environmental impact perspective. In the telecommuting program illustration, without a focus on the environment, an organization conceivably could develop a training class about telecommuting and deliver it through on-site training in a location where most participants would need to fly in to attend. Emissions from the flights alone could potentially cancel out any near-term environmental benefits from telecommuting and, depending on the flying distance and commuting time, other, longer-range benefits.

Third, strategic alignment is also critical so that initiatives support the green strategy, not just one department or individual’s point of view. We’ve shown how organizations can formulate initiatives directly from a driving strategic vision with a clear line of traceability between the two. However, grassroots initiatives also need to be evaluated for their alignment with the strategy. Sometimes small pilot programs can demonstrate early success and then be replicated across larger areas of the business, or they can tap into specialized knowledge and high levels of personal interest from individuals who might otherwise never have been exposed to environmental improvement opportunities. In the telecommuting illustration, many companies first used telecommuting to improve the work/life balance for different scenarios, such as an alternative to extended maternity or paternity leave. By identifying how such programs align with a holistic strategic vision, they might be found to easily fit within the boundaries of environmental stewardship objectives as well as work/life balance ones. Occasionally, when exceptional ideas align poorly with a high-level strategic vision, the strategy itself can change and steer the business in a new direction.

Fourth, full-time staffing and organization skill availability are essential practical considerations for most large-scale initiatives, even those outside environmental stewardship. If full-time staffing isn’t possible, the next-best alternative is to articulate clear priorities that support an established roadmap, a detailed project plan, and milestone targets for the team. Dedicated full-time contractors with specialized knowledge and skills can supplement such teams. As another illustration, consider that the initiative for environmental stewardship might be to replace utility-supplied electrical power with electricity from rooftop solar panels; the implementation schedule for this project could slip indefinitely without the business losing a single sale or dollar of revenue. This can occur when projects are staffed predominantly with resources that have other significant commitments outside the environmental-improvement initiative.

Fifth, the business process framework should encourage standardization and commonality wherever possible, especially in large multinational enterprises, to avoid duplicate efforts and establish models that are easily replicated and scalable. The telecommuting illustration is a good example where global processes likely apply, enabling technology can be shared around the world, and governance policies can be adapted regionally from globally common principles.

Sixth, the importance of having an integrated approach to change is difficult to overemphasize when it comes to environmental stewardship. Because a portfolio of initiatives that reduces the environmental impact of a business can potentially affect every functional area, a company must have an integrated view across those initiatives, more traditional business initiatives, and ongoing business operations. Identifying and managing interdependencies across initiatives and across the entire business is important, especially when resources and specialized skills might be in short supply. Training is one area for which integration across initiatives is sensible. For example, an organization can integrate telecommuting training with other awareness training, such as efficient equipment use or desktop computer shut-down policies during nonuse.

Seventh, conscious and explicit benefit tracking is another critical success factor. Benefit tracking usually is preceded by a quantified benefits case so that companies can identify expected benefits, measure key performance indicators, set targets, and report realized benefits when initiatives succeed. Benefit tracking also identifies whether the original assumptions of the benefit case have changed or whether expected value is not being realized. The organization then can identify root causes and implement corrective action. A benefits case also documents qualitative benefits that are difficult to measure but that can be qualitatively evaluated after an initiative is complete.

As more companies announce their intentions to reduce their carbon footprints and improve environmental stewardship in different ways, benefit tracking will grow in importance. To demonstrate that intentions have been achieved, benefit tracking will be important not just at an initiative or project level, but also at a program and enterprise level, where net benefits can be aggregated without “double-counting” them. The goodwill and business value companies generate from announcements on environmental-improvement targets will eventually need to be demonstrated back to customers and shareholders. Demonstrating conformance to potential regulatory requirements is also easier when companies are tracking and reporting benefits.

Eighth, effective performance management is another critical success factor. Companies need to implement appropriate incentives that motivate people to deliver environmentally sound improvements. The balanced scorecards that evaluate employee and team performance can include both environmental impacts and business results. Fortunately, the cultural change required to align environmental improvement results with incentives doesn’t always need to be large. Because many initiatives for environmental stewardship lead to new products and revenue growth, or new efficiencies and cost reductions, environmental performance management often closely parallels business performance improvement. In the telecommuting illustration, an implementation project team could measure success by on-time delivery of the appropriate solution, employees could measure success by whether they use the program in an appropriate manner, managers could measure whether an appropriate percentage of their employees are telecommuting, and executives could measure ongoing benefits, such as reduced real-estate expenses from a smaller on-site workforce.

Ninth, capability, learning, and knowledge management are essential to an enterprise seeking to improve its environmental stewardship. Initiatives for environmental stewardship may start small, possibly focused on just one facility, site, or segment of a product portfolio. However, when the necessary skills are in place and a proven approach succeeds, the company can replicate such initiatives across more facilities or roll them out to a larger part of the organization. Without effective learning and knowledge management, each new initiative will essentially need to start from scratch, and the value of learning from similar projects will be minimal. Organizational skills and new subject matter expertise will also be needed. To strategically staff initiatives, an enterprise needs visibility into its existing capabilities and capability gaps and to have a clear path to fill those gaps.

Tenth, deployment management is the final critical success factor. Businesses must plan, govern, and coordinate initiatives and the portfolio of projects, to deliver the right outcomes. Deployment management can take many forms, depending on the level of autonomy with which various business units operate (command-and-control organizations versus decentralized, consensus-driven, or matrix organizations) and also the portfolio complexity of the initiatives in the roadmap. Strong and experienced project management is also a factor in success.