3. Green Strategy Supports Operational Improvements

3.1. Drive Operational Decisions and Initiatives That Improve the Environment

In addition to complementing and strengthening the effectiveness of a traditional business strategy, green strategy drives decisions and transformation initiatives at the operating, organizational, information, and applications levels of the strategy pyramid. (Refer back to Figure 2.3 to see this pyramid.) Transformation initiatives that are aligned with a green strategy can also improve the supporting infrastructure (bottom) layer of the strategy pyramid, which includes hardware and equipment. This section addresses each of these lower levels of the strategy pyramid.

3.1.1. Processes, Supply Chains, and Facilities

Green strategies have frequently targeted facilities. Office buildings, manufacturing operations, retail sites, and other key facilities are areas where businesses can easily measure energy consumed and identify improvement opportunities. Environmental impact–improvement efforts and initiatives in this area range from targeting human behavior and small retrofits, to focusing on large-scale construction and renovation.

For example, one Fortune 50 company in the industrial sector has retrofitted the light switches in its U.S. office buildings with motion-sensitive switches. If a conference room or common area of a building is not being used, the lights turn off automatically to save energy and reduce costs. This kind of retrofit is now common. Although this seems like a relatively low-impact activity, it’s easy to envision the potentially significant impact of having every light switch in developed countries operate by motion sensitivity.

In another example, the Ben & Jerry’s ice cream company started testing more environmentally clean freezers in 2008.[1] In a much larger move in 2008, the University of California, San Diego, launched construction on a sustainable-energy program as part of a goal to be the “greenest university” in the U.S. Photovoltaic solar arrays will be installed on the university’s rooftops, and the project also includes biogas fuel cells and wind-generated energy.[2]

Numerous technologies are available, and companies need to evaluate what green technology makes the most sense, depending on the local climate and facility function. The availability and effectiveness of items such as solar cells and wind farms to generate electricity, or solar water and air heaters will vary based on geographic location and business purpose.

But not all organizations have proactively improved their facilities. In one example, a recruiting officer from one Fortune 500 global company recently interviewed university seniors to fill open positions. In the interviews, nearly half of the candidates asked what the company was doing in terms of green building and facility initiatives. Without an enterprise-level green strategy, the answer to their question was unimpressive to the interviewees. In this scenario, the most freshly educated minds were asking something that one of the most forward-looking companies could not answer. Shortly afterward, the department responsible for business real estate put the wheels in motion to develop a green strategy whose scope included all facilities.

Green strategies have also targeted process improvement opportunities. Six Sigma, a business management strategy and related set of quality-management methods, and Lean practices for organizing and managing business processes, have already made significant progress in reducing waste, especially from manufacturing and back-office processes. Chapter 5, “Transformation Methods and Green Sigma,” further explains Six Sigma and Lean practices. Muda, a Japanese term for anything wasteful that does not add value, from Lean practices, provides a basis for identifying waste that can be reduced or eliminated. However, when a green strategy is considered along with cost reduction and optimization in process-transformation initiatives, outcomes can be different and additional opportunities can be captured. How many times has a gap assessment between a current process and a desired process included analysis of pain points and deficiencies such as “very little recycling of paper and plastic” or “too much paper and raw materials used”? Gap assessments are frequently used in business-process reengineering and other transformation initiatives, but “green” gaps are often neglected.

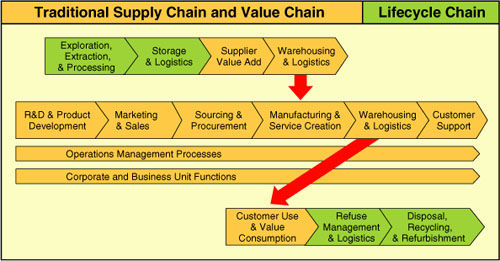

Process improvement opportunities to increase efficiency, reduce waste, and reduce a company’s carbon footprint represent only a small part of the value companies can capture as environmental stewards in this area. Companies can transform and leverage processes throughout the traditional supply chain, value chain, and entire lifecycle chain to achieve not just cost-reduction goals, but also revenue growth, customer loyalty, and brand recognition.

Figure 3.1 shows how the lifecycle chain is constructed from the traditional supply chain inside the “four walls” of a company. It also includes processes from the traditional value chain that include supplier and customer activity, and expands beyond traditional boundaries to include farther-reaching processes for both upstream and downstream operations. The lifecycle-chain view of an organization, and visibility to the full scope of processes a company depends upon, provides new insight into proactive measures that business can take to positively impact the environment.

As with many elements of green strategy, a number of companies have already applied lifecycle-chain principles to innovate and establish some leading practices. For example, Hewlett-Packard has sold its inkjet printer cartridges with an envelope that customers can use to recycle their old cartridges at no cost and with relatively little effort. This seemingly simple tool enables an original manufacturer to reliably retrieve its used products, dispersed over millions of sites, back to a central location for refurbishment or disposal. The obvious cost and environmental impact advantages of efficient refurbishment instead of original manufacturing are only a few of the benefits from this kind of program. Participating in the recycling program strengthens customer loyalty and brand association with environmental stewardship. Motorola is another company that offers a similar option to its customers: Customers can use prepaid envelopes that are bundled with many new cellular phones to send old phones back to the company for recycling.[3] Motorola, Nokia, and Sony Ericsson are just a few companies making it easy to recycle products from their industry by enabling consumers to print prepaid envelope labels directly from the Internet.[4, 5] Equipment manufacturers that are taking responsibility for the refurbishment and recycling of their products, and also involve end customers in the process, might be viewed as just a sophisticated version of reusable soda and milk bottles that were common decades ago. Today the practice still strengthens brand recognition and customer loyalty.

Some companies in the consumer electronics industry are taking this concept a step further by offering to take back any of the products they have sold in the past (discussed earlier in Chapter 1, “Driving Forces and Challenges That Organizations Face,” Section 1.3.3.3). Manufacturers bear the cost of refurbishment or disposal, but customer loyalty and brand awareness are strengthened. Not only does this benefit the environment by keeping hazardous waste out of landfills, but new legislation in some countries also is making this practice mandatory for companies to sell their products there.

When The Home Depot announced its free national Compact Fluorescent Light (CFL) bulb–recycling initiative to customers, the company joined the ranks of others that are innovating their offerings and services in ways that consider the broader lifecycle chain. Heralded as the first service of its kind that a U.S. retailer made so widely available, the initiative provides customers with options for making environmentally conscious decisions, from purchase to disposal.[6] This program gives customers a good reason to return to the store and strengthens customer loyalty, but it also helps solve the practical problem of proper disposal because each CFL bulb contains a few milligrams of mercury. The program might even be a catalyst for acquiring new customers because some people who purchase CFL bulbs from other retailers might dispose of the used product at The Home Depot and also shop for new merchandise there at the same time. Leading by example, the company announced at the same time that it would switch from incandescent to fluorescent lighting in its retail store showrooms, to reduce energy consumption and improve the company’s impact on the environment. For an idea of the waste reduced, one study from Greenpeace estimates that households in the U.K. could save 15 percent on electric bills simply by switching to CFL technology.[7] Best Buy followed a similar strategy when it launched its free e-waste recycling program.[8]

Large and medium-size companies are also leveraging knowledge of the lifecycle chain by instituting programs to collect and properly dispose of batteries and electronic equipment from employee use. By recognizing that disposal of these products should be treated differently than disposal of other biodegradable refuse, and instituting appropriate recycling programs, companies are proactively reducing their negative environmental impact. To extend the benefit, some companies encourage employees to leverage such hazardous waste–disposal programs by bringing their personal-use batteries and small electronics into the office for disposal instead of discarding them with household trash.

Innovative approaches to improving environmental stewardship from lifecycle-chain insights are large in number, but they are still only beginning to reflect their full potential. Radio frequency identification (RFID) technology is already being use to manage returnable containers and optimize logistics in the automotive industry.[9] RFID technology has also been tested where it could streamline checkout procedures in grocery stores and retail locations, and Global Positioning System (GPS) technology is being applied to track and optimize logistics functions around the world. Conceivably, companies could apply similar technology further down the lifecycle chain, to help automatically identify and separate recyclable material from refuse headed for dumping or landfill sites.

Not all the lifecycle-chain innovations come from improvements to downstream activities. In the pulp and paper industry, traceability of wood products and recycled raw materials back to the forest or other source is already important for paper manufacturers to make sure they are following established environmental stewardship practices and can confidently communicate compliance to customers. For example, International Paper is able to demonstrate its commitment to sustainable forest management through third-party certification to a number of independent standards, including the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI), the Switzerland-based Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), and the Brazilian Forest Certification Standards (Cerflor).[10] For building materials such as lumber, organizations such as the FSC and the U.S. Green Building Council have developed certification standards. Companies can stamp their wood products with a mill’s FSC chain-of-custody certification number, which enables it to be traced back to the originating forest. Such traceability gives lumber mills a means of communicating to their customers that the wood they purchase was harvested in a sustainable manner.

More companies are also finding ways to improve their environmental stewardship by “fracturing and splicing” lifecycle chains together from different industries. For example, when the U.K. online entertainment guide Localnightsout.com pledged to plant a tree for every new paid display on the web site[11], the company essentially fractured its lifecycle chain at its sales and marketing link, and spliced it with a “manufacturing” step in forestry.

Corporations that have taken a lifecycle-chain perspective to identify strategic, environmental improvement opportunities are already benefiting from an early-mover advantage, establishing favorable market positions with their increasingly green customers.

3.1.2. Organizational Roles, Skills, and Core Competencies

When a company creates and pursues a green strategy, its plan will undoubtedly affect its organizational strategy and core competencies. Some studies estimate that up to 500,000 new jobs across all income levels in ecologically responsible trades will be created in just a few years.[12] When the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Green Jobs Act in 2007, it paved the way for government funding of “green-collar” job training by authorizing up to $125 million per year to create an energy efficiency and renewable energy worker training program as an amendment to the existing Workforce Investment Act (WIA). The Green Jobs Act targets skills in a range of industries that include energy efficient building, construction, and retrofits; renewable electric power; energy-efficient vehicles; biofuels; and manufacturing that produces sustainable products and uses sustainable processes and materials.[13] The act has achieved some success, although the $22.5 million approved in the 2009 budget for the green-collar jobs training initiative “is well short of the $125 million that was authorized” originally.[14] If U.S. President Barack Obama’s campaign policy objectives from 2008 are fully realized, $150 billion will be invested over ten years to create a much larger population of five million green-collar jobs.[15]

Entirely new core competencies are foreseeable to effectively execute a green strategy. Product engineers will need to have the competency to design products that use less energy and fewer raw materials to produce, and consume less energy and fewer resources when in use. Energy auditors will be in higher demand as the need for facility energy audits increases and building energy-efficiency analysis needs increase. Environmental management skills will need to be developed to monitor performance, and protect and conserve natural resources. Today’s landscapers and maintenance workers will benefit from acquiring arborist competencies that give them an understanding of conservation and renewable resource use.[16]

Other existing roles will need to adapt to accommodate a greener job market. For example, finance and accounting professionals could learn how to manage and take advantage of carbon emission offsets. Drivers of all sorts, from pizza delivery workers and commuters to cross-country truck drivers, will benefit their employing organizations by learning energy-efficient driving practices. Countries such as Sweden already incorporate learning these eco- and energy-efficient competencies into the knowledge requirements to receive a driver’s license. A new European Union directive on mandatory periodic training of bus, coach, and truck drivers includes sessions on fuel-efficient driving and safety.[17] Office workers at many companies that have not already started telecommuting programs will need to learn remote-work practices and the associated technology to reduce the environmental impact from commuting. Others in business operations will learn how to reduce carbon emissions and lower natural resource consumption, such as water and energy, at least partly by using traditional measures, such as cost, quality, cycle time, and inventory levels.

Few organizational roles are unaffected when a company adopts a green strategy. Facilities managers become more accountable for energy conservation, custodial staff has a higher responsibility to handle recyclable material, managers become responsible for reporting performance against environmental key performance indicators and are accountable for results, and executives become accountable for environmental stewardship, sustainability progress, and regulatory compliance.

In addition to skills and competencies, other organizational development tools should be aligned with the objectives of a green strategy. Performance management reviews are more likely to reward green contributions in the balanced scorecard that employees are assessed against, typically on an annual, semiannual, or project-by-project basis. High-potential employees and recruiters will likely recognize a need for environmental awareness in candidates. Training will likely include green elements and the impact employees can have on improving the environment. Communication and awareness campaigns will likely emphasize green objectives, highlight key successes, and recognize significant green contributors.

Many scenarios are being tested and turned into leading practices, with more options yet to explore. We can imagine a day in the near future when it’s feasible for companies with effective recycling programs to match the redemption value of recycled beverage containers to fund, for example, an employee-chosen donation program. Or perhaps the day will come when human resource professionals require training on the legal implications of hiring practices that discriminate against employees with long commuting distances that result in a larger carbon footprint for the organization.

Ultimately, new roles will evolve, with critical responsibilities for delivering results on a green strategy. The Chief Sustainability Officer (CSO) role is just one such example.

3.1.3. Data Visibility, Reports, Systems, Platforms, Hardware, and Equipment

Information visibility and the enabling technology should be aligned with a green strategy so that investments in information technology (IT) are not wasted and expected benefits can be achieved. Although IT accounts for only 2 percent of global carbon emissions, it can contribute significantly to controlling and reducing as much as 98 percent of the carbon dioxide–equivalent emissions caused by other activities across all industries.[18] We can leverage technology to significantly manage and reduce environmental impacts of all sorts. More companies are applying RFID and GPS technology, along with vehicle and container routing-optimization software, to optimize supply-chain activities. Companies are also using optimization technology to support carbon trading and enable such capabilities as model-based optimization of supply chains and logistics activities.

Technology solutions that simply increase the efficiency and effectiveness of business activity while reducing waste can have a significant beneficial impact on the environment. Mature solutions already exist to enable web conferencing, videoconferencing, online chatting, virtual collaboration, e-mail, and voice over IP. Many companies are deploying these solutions to reduce the need for air travel and employee commuting into a physical office space. Wireless and portable technologies, such as cell phones, personal data assistants (PDA), highway-navigation computers, laptop computers, and Internet access, have made it much easier to do business practically anywhere. But fewer enterprises have taught employees the proper use of these technologies to reduce environmental impact. Using e-mail instead of traditional mail, traditional mail instead of overnight delivery, virtual conferencing instead of air travel, and electronic files instead of paper printouts are all technology-enabled practices that are apparently obvious, but barriers often exist to their full adoption. Sometimes the barriers are eliminated by training employees on how to use the technology, and other times cultural and policy barriers are strong enough to prevent their effective use. For example, by traditional policy standards, videoconferencing infrastructure and its use might appear costly. However, savings from less air travel could more than offset those costs. Through information technology, companies can monitor enabling tools, set improvement targets, and report progress. For example, an increase in telecommuting can correspond to a measurable decrease in physical commuting, and an increase in videoconference usage can correspond to a measurable reduction in air travel.

A different kind of opportunity exists for reducing paper consumption at some companies that are learning to operate in a more virtual, paperless office environment. For many companies, the information age has only led to faster printing technology that spurs increased paper consumption, instead of motivating a more paperless work environment. By monitoring the printer infrastructure, understanding improvement areas, and setting waste-reduction targets as part of a holistic green strategy, reducing waste can often be a simple matter of education and cultural change.

Companies can also apply technology to manage and report information so that business leaders can make better decisions that improve environmental stewardship. Solutions are now available that enable wired or wireless sensors to feed data from processes and other business operations into a data warehouse, and software can analyze and report on trends, apply limits, and even initiate and manage alarms so that process owners can take immediate action when real-time corrections are beneficial. Chapter 5 discusses this approach and its corresponding benefits.

The electronic and computer infrastructure itself also deserves consideration in green-strategy formulation. Green data centers are growing their market share and beginning to replace older, less energy-efficient server systems. Companies are also beginning to consider environmental impact along with other factors, such as labor pools with appropriate skills and labor rates, when choosing locations for new data centers. Because data centers generate heat and require sophisticated temperature controls, one consideration could be to choose a location that has a lower average outside temperature, to lower cooling costs through heat exchange. Other considerations could include alternative uses for the heat generated by a data center. A straightforward application of heat-exchanger technology could use the heat energy from a data center to heat air, water, or other liquids, to reduce the overall environmental impact from other facility operations.

Because the majority of computer electronics have ever-shortening lifecycles and include some toxic materials, procurement from responsible suppliers and disposal through appropriate channels easily fits within the scope of a green strategy. One study from Forrester Research, Inc., found that 85 percent of IT procurement and operations professionals in U.S. companies said environmental concerns were important in planning their IT operations. And 72 percent were aware of efforts by their vendors to promote “green IT” in the design, operations, and disposal of IT products. The needed awareness to act on a green strategy is largely in place. However, 78 percent of the study respondents said that they haven’t included green IT in their evaluation and selection criteria for IT systems and devices.[19] Having a green strategy in place could easily fill this gap between awareness and action. Being green could be as simple as emphasizing energy efficiency in computing, but it could also put preference on selecting products from vendors that have environmentally friendly sourcing, manufacturing, delivery, and disposal operations.

As in other areas of business strategy, the most sophisticated technology solution is not always the answer to enabling a green strategy. The trend of using plasma or LCD display screens in place of printed or mechanical displays represents a move toward larger carbon footprints. These television-style displays are now used for everything from advertising in shopping malls and travel information at transportation hubs, to announcements and other messages posted at building entryways. Motion-sensitive switches could be one way of lowering the impact of this trend without reversing it.

Electronics manufacturers will inevitably face the challenge of balancing the production cost and retail price of their products with energy efficiency and functionality. In one example, the trend to move from analog to digital solutions makes it easier to integrate different products such as printers, copiers, and fax machines, but still might represent a move toward higher energy consumption. But the trade-offs are not simple to evaluate. If businesses purchase one integrated digital product instead of three traditional ones, the lifecycle-chain impact to the environment could be lower. Electronics suppliers that provide relevant, quantified information so that their business customers can weigh the trade-offs and make decisions to support green strategies would be providing a useful service in support of environmental stewardship.

Technology infrastructure is much broader than electronics and computer hardware. Businesses that own car fleets can explore including hybrid vehicles in their mix. For example, Enterprise Rent-a-Car and Wal-Mart have both increased the number of hybrid or alternative vehicles in their fleets.[20] In other examples, some of the world’s most advanced warehouse facilities have already eliminated forklifts and heavy machinery with engines that consume natural gas in favor of electric-powered equipment.

Facilities across all industries are using renewable electricity from solar-, wind-, and water-generation technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprints. Many industries are also using technology to manufacture biofuels such as ethanol and biodiesel from corn grain or vegetable oil to replace fossil fuel consumption. Some industries are applying technology to operate and maintain water treatment plants and manage water supplies, as water management becomes more critical. Industry-specific technology solutions are also being developed, tested, and deployed as companies implement green strategy. For example, clean coal technology includes a portfolio of tools to reduce the environmental impact of burning coal as a source of energy.

These are only a few of the many examples that illustrate how an enterprise-level green strategy has the potential to impact nearly every area of a company’s operations and can significantly impact both top-line revenue growth and bottom-line cost savings.

3.2. Support Actions with Attractive Value Propositions

Assigning value to environmental benefits that are typically qualitative is important when understanding a program’s total green value proposition. Green value propositions include benefits to the company’s working environment by improving buildings and facilities, benefits to the community, and impacts that improve the global environment. A green strategy should generally lead to cost-effective transformation initiatives that meet or exceed regulatory requirements.

Net present value (NPV), return on investment (ROI), and internal rate of return (IRR) are all frequently calculated measures of value used to prioritize business transformation initiatives and other projects. Cost reduction, revenue growth, level of fit with corporate strategy, strength of support for regulatory compliance, and risk reduction are all carefully evaluated. However, environmental benefit, carbon footprint reduction, water management improvement, and other factors that improve environmental stewardship aren’t yet routinely included in prioritizing new initiatives and programs. This new dimension of value is not always difficult to evaluate. For example, as the economic value of carbon emissions becomes clearer through such programs as carbon trading, it’s also easier to quantify that aspect of environmental stewardship in a value proposition.

When compared to traditional approaches, evaluating the green elements of an initiative involves a number of differences. Enterprises must understand these differences as they prioritize opportunities and make investment decisions as part of a green strategy.

First, the timeline for achieving a break-even ROI will likely be longer where startup costs are high but benefits are steady. Businesses can easily compute financial benefits from many initiatives that positively impact the environment by comparing current methods with their lower-cost green counterparts. Solar-, wind-, and hydro-generated electricity offer relatively high initial startup costs when implemented on-site—but after installation, they typically offer a positive financial return during their useful lifespan when compared to the usual utility bills. For businesses that look for their investments to break even after two to five years or sooner, the decision to make an investment in sustainable energy with a break-even point that is further out in the future can be difficult. Long-range business cases such as this require assumptions for items such as energy price over a long period of time. If actual prices are higher than originally assumed, the realized benefits will be better than expected. But if energy prices are lower, the realized benefits will be worse than expected. Accounting for traded carbon credits can further increase financial benefits when excess credits that result from emissions-reduction initiatives are sold at a prevailing market price.

Now that many enterprises have the choice to purchase electricity from utility companies that is generated from renewable and sustainable sources, they can make quantitative comparisons between installing on-site energy generation and relying on utilities to provide it for them. Skeptics that question the practice of purchasing green power from utilities argue that, by doing this, companies are avoiding their potential to move toward being carbon neutral within the four walls of the enterprise. Yet if every business was willing to bear the higher cost of electricity from renewable sources from utility companies, economies of scale would inevitably lead to lower prices that could be virtually unaffected by fluctuations in fossil fuel prices.

Second, product differentiation can be easier to achieve, and possibly easier to sustain, while the green movement continues to strengthen and its mass appeal widens. Differentiation in the marketplace frequently leads directly to market share and revenue growth, higher margins for a longer period of time, and stronger customer loyalty for cross-selling and up-selling opportunities. With the appropriate assumptions, businesses can quantify these benefits as an input into the value proposition and business case. For example, Lighting Unlimited, a company based in Florida that sells lighting fixtures and ceiling fans, learned that investing in carrying and promoting Energy Star–qualified products was an easy way to gain local market share. In just one year, sales of these differentiated products grew from 0 percent to 5 percent of total sales. According the company’s president, Bert Heuser, “Advertising the Energy Star products we sell was a simple investment with a huge payback.”[21]

Third, new initiatives and programs with soft benefits might receive more consideration under a green strategy, such as employee morale, lower attrition, favorable press releases, community goodwill, and more sustainable costs in a trend of rising or fluctuating fuel prices. Analysts predict that the green movement and changing consumer preferences will ultimately require businesses to routinely consider environmental stewardship in their investment decisions. In one 2008 survey of CEOs in northeastern Wisconsin, nearly 70 percent of the executives said that customer demand for an improved environmental impact was an important motivator for them to do so in their business.[22] Another survey of retailers identified competitive advantage as the top driver of sustainability programs in that industry.[23] Everything from product-development projects and process-improvement initiatives, to customer service and community involvement will be affected.

Fourth, legislative action and government incentives might contribute more to the value proposition of initiatives and programs that align with a green strategy, whether in place or anticipated, local or national, domestic or global. Legislation is already being drafted and passed that increases requirements for businesses to improve their environmental stewardship, and those that are staying ahead of the regulations are able to proactively transform their products and operations instead of reactively responding to government-imposed constraints.

Fifth, new risks and risk-mitigation approaches will emerge as new technology, new organizational skills, and change-management needs are considered. For example, low aspirations for environmental stewardship and correspondingly small investments would certainly be low-risk from a transformation perspective for many companies—where maintaining the status quo might be all that is required. However, the downside risk of noncompliance with new legislation—losing preferred supplier status with environmentally advanced business partners, losing market share to more advanced competitors, or experiencing increased employee attrition—could drive companies to set aspirations higher and increase the value of initiatives that meet those aspirations. Chapter 1 showed that businesses can view the driving forces behind environmental stewardship from the perspective of risk in different areas. With this perspective, it’s clear that businesses can achieve tremendous value from having a green strategy and mitigating risk with the appropriate initiatives.

Business leaders and decision makers increasingly miss out on significant benefits because they do not consider green opportunities in a strategic context. S. L. Hart appropriately describes “greening” as being about more than cost reduction and explains that it can actually be a major source of revenue growth.[24] Stonyfield Farm, the third-largest yogurt producer in the U.S., has had an enterprise-level green strategy since it was founded in 1983. Its CEO, Gary Hirshberg, emphasizes that businesses need to be convinced of the “economic benefits of going green” and that “Stonyfield proves that you can make money working for the planet instead of against it.”[25]

3.3. Steps to Develop a Green Strategy

As most business leaders already know, simply because a strategy has not been written or formally articulated doesn’t mean that one isn’t being followed, and vice versa. However, when a strategy and its objectives are well described and communicated to an organization, it’s easier for employees to align their activities in collaborative environments, allocate their time appropriately with competing priorities, and make decisions that drive progress toward common goals. In addition, when successes are achieved and an explicit strategy is in place, it’s easier to capture and widely disseminate lessons learned, sustain improvements and maintain best practices, and leverage the experience so that similar benefits can be captured across the entire enterprise.

The first step for an enterprise to develop a green strategy is to assess the current green state of operations and initiatives that have been completed or are underway. A maturity assessment of each area of the strategy pyramid against a maturity model, along with assessing the adoption level of leading practices, can clearly show the areas of a business that are advanced and others that might not even have a basic level of green awareness.

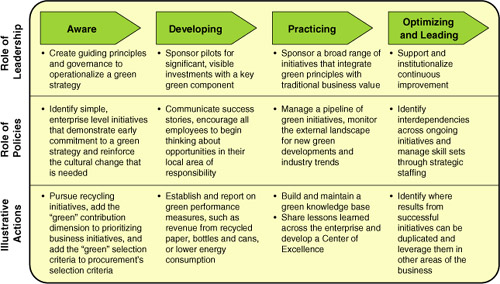

Figure 3.2 illustrates a range of maturity for one green strategy maturity model. As companies move from a low, “aware” level of maturity to higher levels, the role of leadership changes, the role of policies and governance becomes more sophisticated, and actions become an increasingly integral part of a changed corporate culture that continuously scans for new opportunities to improve environmental stewardship.

Figure 3.2 Green strategy maturity model: maturity range

Source: Journal of Business Strategy

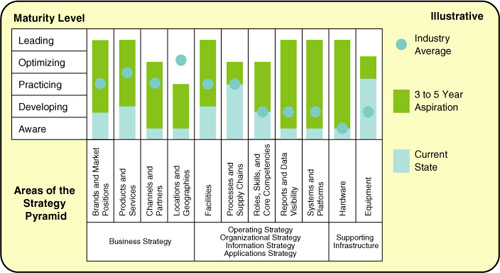

Even companies that rank low in a green-maturity assessment can start in sensible places to build a green strategy. When a maturity assessment is performed to characterize the current state, it’s always sensible to consider future aspirations and how the assessment compares to other companies. Are the aspirations to have base-level capabilities, be competitive with peers, or achieve differentiation? For most businesses, the answer to these questions depends on the area of the strategy pyramid under consideration, and the possible trade-off between downside risk and upside benefit from transforming to achieve different levels of maturity.

Figure 3.3 illustrates one analysis framework that enables a company to assess its current state of green strategy against its own aspirations, and against industry leaders or averages for every level of the strategy pyramid from Figure 2.3. Detailed descriptions of aware, developing, practicing, optimizing, and leading companies; the positioning of other companies within and across industries; and a company’s current level of maturity can all guide an organization in establishing its future aspirations. Wherever a company’s aspirations are meaningfully different from its current maturity level, the company can formulate a green strategy to close the gap between the current and desired state. Chapter 4, “Make Green Strategy Actionable with a Proven Approach,” describes one method for defining such gaps, based on strategic imperatives, and formulating actionable initiatives and roadmaps to fill them.

Figure 3.3 Green strategy maturing model: analysis framework

Source: Journal of Business Strategy

Many businesses have already made significant progress with initiatives that fit within the scope of a green strategy. However, few companies have taken the broadest view of the green possibilities that are available today, and the enormous potential those possibilities have when considered in the context of the whole enterprise. It’s not difficult to find a corporation today in which employees are eager to discuss large, focused efforts of their company aimed at improving the environment, but they still have difficulty locating a properly labeled recycle bin for beverage containers when needed. Although most enterprises have undertaken some form of green initiative, few of them have yet to establish an enterprise-level green strategy.

Organizations can take advantage of well-developed assessment models. Maturity models and diagnostic tools can both play important roles in strategy formulation. Chapter 9, “Business Considerations for Technology Solutions,” Section 9.4, describes these diagnostic tools.

Elements to consider when developing a green strategy include the driving and restraining forces in the enterprise, which make strategic transformation easier or more difficult to achieve. For example, an organizational culture in which business transformation and innovation are common and project management skills are strong represents one driving force that facilitates the implementation of a green strategy. Another driving force might be an advanced technology infrastructure and scalable information architecture that already enables effective business-process monitoring and reporting, to easily accommodate new environmental reporting measures. Existing competence and subject-matter expertise in essential areas of environmental stewardship, process optimization skills, and product development competencies can also be important driving forces for easier strategy implementation. Resource-allocation practices at some companies can represent a restraining force, requiring changes before initiatives for environmental stewardship get priority funding and the most skilled personnel. Employee performance management and company recognition and reward practices can also be restraining forces to strategy implementation without appropriate changes; realigning performance metrics might be necessary before initiatives for environmental stewardship attract the attention and interest of top talent.

After identifying the forces driving and restraining strategy implementation and the associated change, companies can use one frequently used tool to analyze them: the Force-Field Analysis.[26] A Force-Field Analysis enables companies to weight each force and visually shows both the driving forces pushing in one direction and the restraining forces pushing in the opposite direction. By reducing or eliminating the restraining forces and strengthening the driving forces, a company can dramatically reduce the effort required to implement a green strategy.

The benefits from having a formal, well-articulated green strategy vary by industry and even by individual business, but early adopters can still harness the enormous potential to opportunistically position themselves with a sustainable green strategic advantage. The results of a maturity analysis and subsequent green strategy formulation can then be the basis for developing a set of initiatives and an associated implementation roadmap to close gaps and reach aspirations. Companies should apply the same level of rigor to implement their green strategy as they do for any other element of traditional business strategy. Chapter 4 describes one methodology for accomplishing this task.