CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Business Process Design

Booming competition in an increasingly global marketplace leaves no room for successful companies to harbor internal inefficiencies. Even more importantly, customers are becoming more demanding; if one product or service does not live up to their expectations, there are many more from which to choose. The stakes are high, and so is the penalty for not satisfying the right customers with the right products and services. The quest for internal efficiency and external effectiveness means that organizations must align their internal activities and resources with the external requirements, or to put it differently, business processes must be designed appropriately. To that end, the main objective of this book is to provide the reader with a comprehensive understanding of the wide range of analytical tools that can be used for modeling, analyzing, and ultimately designing business processes. Particular emphasis is placed on discrete event simulation, as it represents one of the most flexible and powerful tools available for these purposes.

However, before investigating the different analytical tools in Chapters 4 through 11, we need to understand what business processes and process design are all about. This first chapter is devoted to a detailed definition of business processes and business process design, including the concepts of process hierarchies, process architecture, and incremental process improvement as opposed to process design. An important distinction made in this respect is between the activities of designing a process and implementing the design; the former is the focus of this book.

This introductory chapter also discusses the importance of business process design for the overall business performance and the organization’s business strategy. The last section of this chapter explores why inefficient and ineffective business processes come to exist in the first place.

Chapter 2 deals with the important issues of managing and improving processes, including issues of implementation and change management. Chapter 3 then discusses a simulation-based methodology for business process design projects. This can be construed as a road map for the remaining eight chapters of this book, which focus on tools and modeling.

1.1 What Is a Business Process?

From a pragmatic point of view, a business process describes how something is done in an organization. However, the in-depth analysis and design of business processes, the theme of this book, require further examination.

Let us start by dissecting the words business and process. Most people probably would contest that they have a clear notion about what a business is. In broad terms, we will define a business as “an organizational entity that deploys resources to provide customers with desired products or services.” This definition serves our purposes because it encompasses profit-maximizing firms and supply chains, as well as nonprofit organizations and governmental agencies.

A process is a somewhat more ambiguous concept with different meanings, depending on the context in which it is used. For example, a biologist or medical doctor refers to breathing as a life-sustaining process. In mathematics or engineering, the concept of random or deterministic processes describes event occurrences. In politics, the importance of election processes is obvious, in education a key concept is the learning process, and so on. Merriam Webster's Dictionary, online 11th edition, defines process as (i) a natural phenomenon marked by gradual changes that lead to a particular result, (ii) a natural continuing activity or function, or (iii) a series of actions or operations conducing to an end. The last of these definitions is of particular interest for our understanding of business processes, because it leads into the traditional high-level definition of a process used in the operations management literature: a process specifies the transformation of inputs to outputs. The transformations typically are classified as follows.

- Physical, for instance, the transformation of raw materials to a finished product.

- Locational, for instance, the transportation service provided by an airline.

- Transactional, for instance, banking and transformation of cash into stocks by a brokerage firm.

- Informational, for instance, the transformation of financial data into information in the form of financial statements.

The simple transformation perspective forms the basis for the so-called process view of an organization. (See Figure 1.1.) According to this perspective, any organizational entity or business can be characterized as a process or a network of processes.

The process view makes no assumptions of the types of processes constituting the organization. However, often a process is automatically thought of as a manufacturing or production process. We employ the term business process to emphasize that this book is not focusing on the analysis and design of manufacturing processes per se, although they will be an important subset of the entire set of business processes that define an organization. Table 1.1 provides some examples of generic processes other than traditional production/manufacturing processes that one might expect to find in many businesses. For the remainder of this book, the terms process and business process will be used interchangeably.

The simple transformation model of a process depicted in Figure 1.1 is a powerful starting point for understanding the importance of business processes. However, for purposes of detailed analysis and design of the transformation process itself, we need to go further and look behind the scenes, inside the “black box” model so to speak, at process types, process hierarchies, and determinants of process architecture.

FIGURE 1.1 The Transformation Model of a Process

TABLE 1.1 Examples of Generic Business Processes Other Than Traditional Production and Manufacturing Processes

1.1.1 PROCESS TYPES AND HIERARCHIES

Based on their scope within an organization, processes can be characterized into three different types: individual processes, which are carried out by separate individuals; vertical or functional processes, which are contained within a certain functional unit or department; and horizontal or cross-functional processes, which cut across several functional units (or, in terms of supply chains, even across different companies). See Figure 1.2 for illustration.

FIGURE 1.2 Illustration of Individual, Vertical, and Horizontal Processes

It follows that a hierarchy exists between the three process types in the sense that a cross-functional process typically can be decomposed into a number of connected functional processes or subprocesses, which consist of a number of individual processes. Moving down even further in detail, any process can be broken down into one or more activities that are comprised of a number of tasks. As an illustration, consider the order-fulfillment process in Figure 1.2, which in its entirety is cross functional. However, it consists of functional subprocesses (e.g., in the sales and marketing departments) that receive the order request by phone, process the request, and place a production order with the operations department. The order receiving itself is an activity comprised of the tasks of answering the phone, talking to the customer, and verifying that all necessary information is available to process the order. If we assume that the order-receiving activity is performed by a single employee, this constitutes an example of an individual process.

In terms of process design, cross-functional business processes that are core to the organization and include a significant amount of nonmanufacturing-related activities often offer the greatest potential for improvement. Core processes are defined by Cross et al. (1994) as all the functions and the sequence of activities (regardless of where they reside in the organization), policies and procedures, and supporting systems required to meet a marketplace need through a specific strategy. A core process includes all the functions involved in the development, production, and provision of specific products or services to particular customers. An underlying reason why cross-functional processes often offer high improvement potential compared to functional processes in general, and production/manufacturing processes in particular, is that they are more difficult to coordinate and often suffer from suboptimization1. An important reason for this tendency toward suboptimization is the strong departmental interests inherent in the functional2 organization’s management structure.

Roberts (1994) provides some additional explanations for the high improvement potential of cross-functional business processes.

- Improvements in cross-functional business processes have not kept up with improvements in manufacturing processes over the years. In other words, the current margin for improvement is greater in nonmanufacturing-related business processes.

- Waste and inefficiency are more difficult to detect in cross-functional processes than in functional processes due to increased complexity.

- Cross-functional business processes often devote as little as 5 percent or less of the available process time to activities that deliver value to the customers.

- Customers are five times more likely to take their business elsewhere because of poor service-related business processes than because of poor products.

1.1.2 DETERMINANTS OF THE PROCESS ARCHITECTURE

The process architecture or process structure can be characterized in terms of five main components or elements (see, for example, Anupindi et al. [1999]): the inputs and outputs, the flow units, the network of activities and buffers, the resources, and the information structure, some of which we have touched upon briefly already. To a large extent, process design and analysis has to do with understanding the restrictions and opportunities these elements offer in a particular situation. We will deal with this extensively in Chapters 2 through 9.

Inputs and Outputs

The first step in understanding and modeling a process is to identify its boundaries; that is, its entry and exit points. When that is done, identifying the input needed from the environment in order for the process to produce the desired output is usually fairly straightforward. It is important to recognize that inputs and outputs can be tangible (raw materials, cash, and customers) or intangible (information, energy, and time). To illustrate, consider a manufacturing process where inputs in terms of raw materials and energy enter the process and are transformed into desired products. Another example would be a transportation process where customers enter a bus station in New York as inputs and exit as outputs in Washington. In order to perform the desired transformation, the bus will consume gasoline as input and produce pollution as output. Similarly, a barbershop takes hairy customers as input and produces less hairy customers as output. An example in which inputs and outputs are information or data is an accounting process where unstructured financial data enter as input and a well-structured financial statement is the output. To summarize, the inputs and outputs establish the interaction between the process and its environment.

Flow Unit

A unit of flow or flow unit can be defined as a “transient entity3 that proceeds through various activities and finally exits the process as finished output.” This implies that depending on the context, the flow unit can be a unit of input (e.g.,a customer or raw material), a unit of one or several intermediate products or components (e.g., the frame in a bicycle-assembly process), or a unit of output (e.g.,a serviced customer or finished product). The characteristics and identity of flow units in a system, as well as the points of entry and departure, can vary significantly from process to process. Typical types of flow units include materials, orders, files or documents, requests, customers, patients, products, paper forms, cash, and transactions. A clear understanding and definition of flow units is important when modeling and designing processes because of their immediate impact on capacity and investment levels.

It is customary to refer to the generic unit of flow as a job, and we will use this connotation extensively in Chapters 3 through 9. Moreover, an important measure of flow dynamics is the flow rate, which is the number of jobs that flow through the process per unit of time. Typically, flow rates vary over time and from point to point in the process. We will examine these issues in more detail in Chapter 5.

The Network of Activities and Buffers

From our discussion of process hierarchies, we know that a process is composed of activities. In fact, an accurate way to describe a process would be as a network of activities and buffers through which the flow units or jobs have to pass in order to be transformed from inputs to outputs. Consequently, for in-depth analysis and design of processes, we must identify all relevant activities that define the process and their precedence relationships; that is, the sequence in which the jobs will go through them. To complicate matters, many processes accommodate different types of jobs that will have different paths through the network, implying that the precedence relationships typically are different for different types of jobs. As an example, consider an emergency room, where a patient in cardiac arrest clearly has a different path through the ER process than a walk-in patient with a headache. Moreover, most processes also include buffers between activities, allowing storage of jobs between them. Real-world examples of buffers are waiting rooms at a hospital, finished goods inventory, and lines at an airport security checkpoint. A common goal in business process design is to try to reduce the time jobs spend waiting in buffers and thereby achieve a higher flow rate for the overall process.

Activities can be thought of as micro processes consisting of a collection of tasks. Finding an appropriate level of detail to define an activity is crucial in process analysis. A tradeoff exists between activity and process complexity. Increasing the complexity of the individual activities by letting them include more tasks decreases the complexity of the process description. (See Figure 1.3.) The extreme is when the entire process is defined as one activity and we are back to the simple “black box” input/output transformation model.

Several classifications of process activities have been offered in the literature. Two basic approaches are depicted in Figure 1.4.

Both approaches classify the activities essential for the process to meet the customers’ expectations as value-adding activities. The difference is in the classification of control, and policy and regulatory compliance activities. One approach is based on the belief that although control activities do not directly add value to the customer, they are essential to conducting business. Therefore, these activities should be classified as business-value-adding (also known as control) activities. The contrasting view is a classification based on the belief that anything that does not add value to the customer should be classified as a non-value-adding activity. This classification can be determined by asking the following question: Would your customer be willing to pay for this activity? If the answer is no, then the activity does not add value. It is then believed that control activities, such as checking the credit history of a customer in a credit-approval process, would fall into the category of non-value-adding activities because the customer (in this case, the applicant) would not be willing to pay for such an activity.

FIGURE 1.3 Process Complexity Versus Individual Activity Complexity

To understand the value-adding classification, the concept of value must be addressed. Although this is an elusive concept, for our purposes it is sufficient to recognize that it involves doing the right things and doing things right. Doing the right things means providing the customers with what they want (i.e., being effective). Activities that contribute to transforming the product or service to better conform to the customer’s requirements have the potential to add value. For example, installing the hard drive in a new personal computer brings the product closer to being complete and is, therefore, value adding. However, to be truly value-added, the activity also must be carried out efficiently using a minimum of resources; that is, it must be done right. If this were not the case, waste would occur that could not be eliminated without compromising the process effectiveness. If the hard drive installation were not done properly, resulting in damaged and scrapped hard drives or the need for rework, the installation activity would not be value adding in its true sense. Even though the right activity was performed, it was not done correctly, resulting in more than the minimum amount of resources being consumed. Clearly, this extra resource consumption is something for which the customer would not be willing to pay.

The task of classifying activities should not be taken lightly, because the elimination of non-value-adding activities in a process is one of the cornerstones of designing or redesigning efficient processes. One of the most common and straightforward strategies for eliminating non-value-adding and control activities is the integration of tasks. Task consolidation typically eliminates wasteful activities, because handoffs account for a large percentage of non-value-adding time in many processes. Also, controls (or control activities) are generally in place to make sure that the work performed upstream in the process complies with policies and regulations. Task aggregation tends to eliminate handoffs and controls; therefore, it increases the ratio of value-adding activities to non-value-adding activities (and/or business-value-adding activities).

To illustrate the process of classifying activities, let us consider the famous IBM Credit example, first introduced by Hammer and Champy (1993). IBM Credit is in the business of financing computers, software, and services that the IBM Corporation sells. This is an important business for IBM, because financing customers’ purchases is extremely profitable. The process formerly used consisted of the following sequence of activities.

- Field sales personnel called in requests for financing to a group of 14 people.

- The person taking the call logged information on a piece of paper.

- The paper was taken upstairs to the credit department.

- A specialist (a) entered the information into a computer system and (b) did a credit check.

- The results of the credit check (a) were written on a piece of paper and (b) sent to the business practices department.

- Standard loan contracts were modified to meet customer requirements.

- The request was (a) sent to a “pricer,” where (b) an interest rate was determined.

- The interest rate (a) was written on a piece of paper and (b) sent to a clerical group.

- A quote was developed.

- The quote was sent to field sales via FedEx.

A possible classification of these activities into the categories of value-adding, nonvalue-adding, and business-value-adding appears in Table 1.2.

Note that only a small fraction of the activities are considered to add value to the customer (i.e., the sales field agent). Arguably, the only activity that adds value might be number 9; however, we also have included activity 1 because the customer triggers the process with this activity and activity 6 because the customization of the contract is forced by the peculiarities of each specific request. Handoffs account for a considerable percentage of the non-value-adding activities (3, 5(b), 8(b), and 10). This description does not include all the delays that are likely to occur between handoffs, because in practice, agents in this process did not start working on a request immediately upon receipt. In fact, although the actual work took in total only 90 minutes to perform, the entire process consumed 6 days on average and sometimes took as long as 2 weeks. In Section 3.6.2 of Chapter 3, we will discuss how the process was redesigned to achieve turnaround times of 4 hours on the average.

Resources

Resources are tangible assets that are necessary to perform activities within a process. Examples of resources include the machinery in a job shop, the aircraft of an airline, and the faculty at an educational institution. As these examples imply, resources often are divided into two categories: capital assets (e.g., real estate, machinery, equipment, and computer systems) and labor (i.e., the organization’s employees and the knowledge they possess). As opposed to inputs, which flow through the process and leave, resources are utilized rather than consumed. For example, an airline utilizes resources such as aircraft and personnel to perform the transportation process day after day. At the same time, the jet fuel, which is an input to the process, is not only used but consumed.

TABLE 1.2 Activity Classifications for IBM Credit

Information Structure

The last element needed in order to describe the process architecture is the information structure. The information structure specifies which information is required and which is available in order to make the decisions necessary for performing the activities in a process. For example, consider the inventory replenishment process at a central warehouse; the information structure specifies the information needed in order to implement important operational policies, such as placing an order when the stock level falls below a specified reorder point.

Based on our definition of a business and the exploration of process hierarchies and architecture, a more comprehensive and adequate definition of a business process emerges.

A business process is a network of connected activities and buffers with well-defined boundaries and precedence relationships, which utilize resources to transform inputs into outputs for the purpose of satisfying customer requirements. (See Figure 1.5.)

1.1.3 WORKFLOW MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

The term workflow often is used in connection with process management and process analysis, particularly in the field of information systems. It refers to how a job flows through the process, the activities that are performed on it, the people involved, and the information needed for its completion. The workflow is, therefore, defined by the flow units along with the network of activities and buffers, the resources, and the information structure discussed previously. Management of administrative processes often is referred to as workflow management, and information systems that support workflow management are called workflow management systems. For our purposes, we can think of workflow management as synonymous with process management.

Document processing has a fundamental place in workflow management, as business documents are the common medium for information processes (such as data flow analysis, database storage and retrieval, transaction processing, and network communications) and business processes. Workflow management controls the actions taken on documents moving through a business process. Specifically, workflow management software is used to determine and control who can access which document, what operations employees can perform on a given document, and the sequence of operations that are performed on documents by the workers in the process.

FIGURE 1.5 A Process Defined as a Network of Activities and Buffers with Well-Defined Boundaries Transforming Inputs to Customer Required Outputs Using a Collection of Resources

Workers have access to documents (e.g., purchase orders and travel authorizations) in a workflow management system. These individuals perform operations, such as filling and modifying fields, on the documents. For example, an employee who is planning to take a business trip typically must fill out a travel authorization form to provide information such as destination, dates of travel, and tentative budget. The document might go to a travel office where additional information is added. Then, the form probably goes to a manager, who might approve it as is, ask for additional information, or approve a modified version (for instance, by reducing the proposed travel budget). Finally, the form goes back to the individual requesting the travel funds. This simple example illustrates the control activities that are performed before the request to travel is granted. The activities are performed in sequence to guarantee that the approved budget is not changed at a later stage. Although the sequence is well established and ensures a desired level of control, workflow management software should be capable of handling exceptions (e.g., when the manager determines that it is in the best interest of the company to bypass the normal workflow sequence), reworking loops (e.g., when more information is requested from the originator of the request), and obtaining permissions to modify and update the request before the manager makes a final decision. Workflow management software developers are constantly incorporating additional flexibility into their products so buyers can deal with the increasing complexity of modern business processes without the need for additional computer programming.

1.2 The Essence of Business Process Design

The essence of business process design can be described as how to do things in a good way. Good in this context refers to process efficiency and process effectiveness. The last statement is important; process design is about satisfying customer requirements in an efficient way. An efficient process that does not deliver customer value is useless. A well-designed process does the right things in the right way.

From a more formal perspective, business process design is concerned with configuring the process architecture (i.e., the inputs and outputs, the flow units, the network of activities and buffers, the resources, and the information structure; see Figure 1.5), in a way that satisfies customer requirements in an efficient way. It should be noted that process customers can be internal and external to the organization. However, it is important that the requirements of the internal customers are aligned with the overall business goals, which ultimately means satisfying the desires of the external customers targeted in the business strategy.

Although business process design concerns all types of processes, we have already indicated that for reasons of coordination and suboptimization, it is often most valuable when dealing with complex horizontal processes that cut across the functional or departmental lines of the organization and reach all the way to the end customer. An example is the order-fulfillment process illustrated in Figure 1.2.

The roots of the functional organization date back to the late 1700s, when Adam Smith proposed the concept of the division of labor in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). Referring to the 17 operations required to produce a pin, Smith argued that assigning one task to each of 17 workers would be more efficient and would produce more pins than having 17 workers each autonomously perform all 17 tasks. According to Smith, dividing work into discrete tasks provides the following benefits.

- Each worker’s skill increases by repeatedly performing the same task.

- No time is lost due to switching workers from one task to another.

- Workers are well positioned to develop improved tools and techniques as a result of focusing on a single task.

What Smith’s model does not address is that as products and services become more complex and customers require more varieties of them, the need for many more activities and the coordination of the resulting basic tasks comprising these activities becomes extremely difficult. The division of labor has the goal of creating highly specialized workers who can complete basic tasks efficiently. Even if the workers become highly efficient at their tasks, the process as a whole can be inefficient. Inefficiencies in a process design with the division of labor paradigm are primarily related to the need for handing off work from one station to the next and for coordinating the flow of the jobs in the process. Perhaps the most significant drawbacks associated with handing off work are the delays and errors introduced when a job is passed from worker to worker.

Consider, for example, the traditional approach to designing new products illustrated by Shafer and Meredith (1998). The process typically begins when the marketing department collects information about customers’ needs and desires. This information is then relayed to a research and development (R&D) department, which is responsible for designing the product to meet the customers’ requirements. After the design is completed, it is up to the manufacturing department to produce the product exactly as specified in the design. After the product is produced, it is the responsibility of the sales department to sell it. Finally, after a consumer purchases the product, the customer service department must provide after-sales services such as help with installation and warranty repairs. This process, although involving several departments, appears to have a logical structure, but in reality it is not uncommon that the engineers in R&D design a feature that manufacturing cannot produce or one that can be produced only at a high cost. In this sequential approach (commonly known as “over-the-wall design”), the production problem would not be discovered until after the design is finalized and handed off to manufacturing. Upon discovering the problem, manufacturing would have to send the design back to R&D for modifications. Clearly, each time a design has to go back and forth between R&D and manufacturing, it involves yet another handoff and increases the delay in introducing the new product.

This example illustrates an essential issue often addressed in process design—namely, that completing a set of activities sequentially, one at a time, tends to increase the time required to complete the entire process. In addition, significant delays can occur in the discovery of important information that would have influenced the quality of the output from activities already completed; this tends to extend the completion time even further. The solution is to try to do as many activities as possible in parallel. Sophisticated product development teams use the concept of concurrent engineering4 to avoid the “over-the-wall design” problem and shorten the process time.

As just indicated, the road to a good process design starts with a profound understanding of what the customers want and thereby what the process is supposed to deliver. Although understanding customer preferences and purchasing behavior is a field of study in its own right, for process design purposes, four dimensions of customer requirements are particularly important: cost, quality, response time, and variety. Arriving at a good process design also requires a thorough understanding of the current process (if one exists) and any new enablers that change the rules of the game, such as IT developments, breakthrough technologies, or changes in legislation. A first approach, particularly in redesign situations, is to try to eliminate waste, waiting times, and non-value-adding activities to speed up the process. However, it is important not to get stuck in the old ways of doing things and leverage the power of process design by challenging rooted perceptions of how to do things.

Throughout the book, we will use the terms design and redesign interchangeably because from an analytical point of view, no major difference can be distinguished between designing a new process and redesigning an existing one. This statement hinges on the fact that in this book, we make a clear distinction between designing a process and implementing the design. The latter is a tremendously challenging task that requires good skills in change management and in knowing how to motivate and inspire an organization to change. Ultimately, success will depend on the buy-infrom people at all levels of the organization. In implementing a new design, a big difference is evident between making changes to an existing process and establishing a process in a “greenfield organization” (or an organization that does not have any processes in place), the former usually being the more difficult situation to handle. Because the focus of this book is on the analytical modeling, analysis, and design of processes, from our perspective the analytical approach for design and redesign is the same. We will touch briefly upon the important issues of process and change management in Chapter 2. However, for a more in-depth treatment of this important area, we refer to books solely devoted to the subject of how to achieve and sustain organizational changes; these can be found in the management and human resource literature.

1.2.1 INCREMENTAL PROCESS IMPROVEMENT AND PROCESS DESIGN

In our quest to define the essence of what we refer to as business process design, it is valuable to discuss the relationship between incremental improvement and design. Clearly, both are about how to do things in a good way, and most of the tools for analyzing process that are covered in this book are just as useful in an incremental improvement project as in a design project. However, a subtle but important difference can be detected in terms of the objectives and the degrees of freedom available to a process design team compared to an incremental improvement team. The scope for the former usually far exceeds that of the latter.

The difference between incremental process improvement and process design parallels the difference between systems improvement and systems design that John P. Van Gigch so eloquently described more than 25 years ago (Van Gigch, 1978). Van Gigch’s book championed the notion of a systems approach to problem solving, a field from which process design and reengineering5 have borrowed many concepts. In the following, we adapt Van Gigch’s descriptions to the context of process design, acknowledging that if a system is defined as an assembly or set of related elements, a process is nothing else but an instance of a system.

Many of the problems arising in the practice of designing business processes stem from the inability of managers, planners, analysts, administrators, and the like to differentiate between incremental process improvement and process redesign. Incremental improvement refers to the transformation or change that brings a system closer to standard or normal operating conditions. The concept of incremental improvement carries the connotation that the design of the process is set and that norms for its operation have been established. In this context, improving a process refers to tracing the causes of departures from established operating norms, or investigating how the process can be made to yield better results—results that come closer to meeting the original design objectives. Because the design concept is not questioned, the main problems to be solved are as follows.

- The process does not meet its established goals.

- The process does not yield predicted results.

- The process does not operate as initially intended.

The incremental improvement process starts with a problem definition, and through analysis, we search for elements of components or subprocesses that might provide possible answers to our questions. We then proceed by deduction to draw certain tentative conclusions.

Design also involves transformation and change. However, design is a creative process that questions the assumptions on which old forms have been built. It demands a completely new outlook in order to generate innovative solutions with the capability of increasing process performance significantly. Process design is by nature inductive. (See Chapter 3 for a further discussion of inductive versus deductive thinking.)

1.2.2 AN ILLUSTRATIVE EXAMPLE

To illustrate the power of process design in improving the efficiency and effectiveness of business processes, we will look at an example from the insurance industry, adapted from Roberts (1994).

Consider the claims-handling process of a large insurance company. Sensing competitive pressure coupled with the need to be more responsive to its customers, the company decided to overhaul its process for handling claims related to the replacement of automobile glass. The CEO thought that if her plan was successful, she would be able to use any expertise acquired from this relatively low-risk endeavor as a springboard for undertaking even more ambitious redesign projects later. Furthermore, the project would give the company an important head start on the learning curve associated with redesign activities.

The CEO immediately appointed an executive sponsor to shepherd the project. Following some preliminary analysis of the potential payoff and impact, the CEO and the executive sponsor developed a charter for a process design team and collaborated to handpick its members.

Early on, the team created a chart of the existing process to aid in their understanding of things as they were. This chart is depicted in simplified form in Figure 1.6. (In Chapter 4, we will introduce methods and tools for creating several charts for process analysis.) This figure summarizes the following sequence of events for processing claims under the existing configuration.

- The client notifies a local independent agent that she wishes to file a claim for damaged glass. The client is given a claim form and is told to obtain a replacement estimate from a local glass vendor.

- After the client has obtained the estimate and completed the claim form, the independent agent verifies the accuracy of the information and then forwards the claim to one of the regional processing centers.

- The processing center receives the claim and logs its date and time of arrival. A data entry clerk enters the contents of the claim into a computer (mainly for archiving purposes). Then, the form is placed in a hard-copy file and routed, along with the estimate, to a claims representative.

- If the representative is satisfied with the claim, it is passed along to several others in the processing chain, and a check eventually is issued to the client. However, if any problems are associated with the claim, the representative attaches a form and mails a letter back to the client for the necessary corrections.

- Upon receiving the check, the client can go to the local glass vendor and have the glass replaced.

Using the existing process, a client might have to wait one to two weeks before being able to replace his or her automobile glass. If the glass happens to break on a weekend, the process could take even longer.

Given the goal to come up with a radical overhaul of the process, the team recommended the solution depicted in Figure 1.7. The team accomplished this after evaluating a number of process configurations. The evaluation was done in terms of the cost versus the benefits resulting from each configuration.

Structural as well as procedural changes were put into place. Some of these, especially the procedural changes, are not entirely evident simply by contrasting Figures 1.6 and 1.7. The changes in procedures involved the following.

- The claims representative was given final authority to approve the claim.

- A long-term relationship was established with a select number of glass vendors, enabling the company to leverage its purchasing power and to pay the vendor directly. Furthermore, because the prices are now prenegotiated, it is no longer necessary to obtain an estimate from the vendor. (Note that this procedural change is similar to the well-established total quality management [TQM] notion of vendor certification.)

- Rather than going through a local agent, obtaining an estimate, and filling out a form, the client now simply contacts the processing center directly by phone to register a claim.

The structural changes are manifested in the following sequence of events, which describe the flow of the process.

- Using a newly installed, 24-hour hot line, the client speaks directly with a claims representative at one of the company’s regional processing centers.

- The claims representative gathers the pertinent information over the phone, enters the data into the computer, and resolves any problems related to the claim on the spot. The representative then tells the client to expect a call from a certain glass vendor, who will make arrangements to repair the glass at the client’s convenience.

- Because the claim now exists as an electronic file that can be shared through a local area network (LAN), the accounting department can immediately begin processing a check that will be sent directly to the local glass vendor.

A number of significant benefits—some more quantifiable than others—resulted from changing the process to introduce a new design.

- The client can now have the glass repaired in as little as 24 hours versus 10 days. This represents a 90 percent improvement in the process cycle time (i.e., the elapsed time from when the claim is called in until the glass is replaced).

- The client has less work to do because a single phone call sets the process in motion. Also, the client is no longer required to obtain a repair estimate.

- Problems are handled when the call is initiated, thus preventing further delays in the process.

- Problems with lost or mishandled claims virtually disappear.

- The claim now passes through fewer hands, resulting in lower costs. By establishing a long-term relationship with a select number of glass vendors, the company is able to leverage its purchasing power to obtain a 30 percent to 40 percent savings on a paid claim.

- Because fewer glass vendors are involved, a consolidated monthly payment can be made to each approved vendor, resulting in additional savings in handling costs. The company now issues 98 percent fewer checks.

- By dealing with preapproved glass vendors, the company can be assured of consistent and reliable service.

- The claims representatives feel a greater sense of ownership in the process, because they have broader responsibilities and expanded approval authority.

It is evident that the new process was designed by framing the situation in these terms: How do we settle claims in a manner that will cause the least impact on the client while minimizing processing costs? If instead they had asked How can we streamline the existing process to make it more efficient? their inquiry might not have removed the independent agent from the processing chain. The fundamental difference between these two questions is that the first one is likely to lead to a radical change in the process design because it goes to the core issue of how to best satisfy the customer requirements, and the second one is likely to lead to the introduction of technology without process change (i.e., automation without redesign). Could further efficiencies still be realized in this process? Without a doubt! This is where an incremental and continuous improvement approach should take over.

1.3 Business Process Design, Overall Business Performance, and Strategy

To put process design into a larger context, we point out some links among process design, overall business performance, and strategy.

1.3.1 BUSINESS PROCESS DESIGN AND OVERALL BUSINESS PERFORMANCE

What is overall business performance and how is it measured? A detailed answer to this question is to a large extent company specific. However, in general terms we can assert that the performance of a business should be measured against its stated goals and objectives.

For a profit-maximizing firm, the overarching objective is usually to maximize long-term profits or shareholder value. In simple terms, this is achieved by consistently, over time, maximizing revenues and minimizing costs, which implies satisfying customer requirements in an efficient way. For nonprofit organizations, it is more difficult to articulate a common goal. However, on a basic level, presumably one objective is to survive and grow while providing customers with the best possible service or products. Consider, for example, a relief organization with the mission of providing shelter and food for people in need. In order to fulfill this mission, the organization must first of all survive, which means that it must maintain a balanced cash flow by raising funds and keeping operational costs at a minimum. Still, to effectively help as many people as possible in the best possible way requires more than just capital and labor resources; it requires a clear understanding of exactly what kind of aid their “customers” need the most. Furthermore, the ability to raise funds in the long run most likely will be related directly to how effectively the organization meets its goals; that is, how well it performs.

To summarize, a fundamental component in overall business performance regardless of the explicitly stated objectives is to satisfy customer requirements in an efficient way. In the long term, this requires well-designed business processes.

1.3.2 BUSINESS PROCESS DESIGN AND STRATEGY

Strategy guides businesses toward their stated objectives and overall performance excellence. In general terms, strategy can be defined as “the unifying theme that aligns all individual decisions made within an organization.”

In principle, profit-maximizing firms address their fundamental objective of earning a return on their investment that exceeds the cost of capital in two ways. Either the firm establishes itself in an industry with above-average returns, or it leverages its competitive advantage over the other firms within an industry to earn a return that exceeds the industry average. These two approaches define two strategy levels that are distinguishable in most large enterprises. The corporate strategy answers the question Which industries should we be in? The business strategy answers the question How should we compete within a given industry?

Although both strategies are of utmost importance, the intensified competition in today’s global economy requires that no matter what industry one operates in, one must be highly competitive. Consequently, a prerequisite for success is an effective business strategy. In fact, nonprofit organizations need to be competitive, as well. For example, the relief organization mentioned previously most likely has to compete against other organizations of the same type for funding. Similarly, a university competes against other universities for students, faculty, and funding.

Developing a business strategy is, therefore, a crucial undertaking in any business. Many different approaches deal with this issue in a structured, step-by-step fashion. However, developing a sound business strategy requires a profound understanding of the organization’s external and internal environment combined with a set of clearly defined, long-term goals. The external environment includes all external factors (e.g., social, political, economical, and technological) that influence the organization’s decisions. Still, in most instances the core external environment is comprised of the firm’s industry or market, defined by its relationship with customers, suppliers, and competitors. The internal environment refers to the organization itself, its goals and values, its resources, its organizational structure, and its systems. This means that understanding the internal environment to a large extent has to do with understanding the hierarchy and structure of all business processes.

A clear understanding of the internal environment promotes an understanding of the organization’s internal strengths and weaknesses. Similarly, in-depth knowledge of the external environment provides insights into the opportunities and threats the organization is facing. Ideally, the business strategy is designed to take advantage of the opportunities by leveraging the internal strengths while avoiding the threats and protecting its weaknesses. This basic approach is referred to as a SWOT analysis.

The link between business process design and the business strategy is obvious when it comes to the internal environment; the internal strengths and weaknesses are to a large extent embodied in the form of well-designed and poorly designed business processes. By carefully redesigning processes, weaknesses can be turned into strengths, and strengths can be further reinforced to assure a competitive advantage. The link to the external environment might be less obvious, but remember that a prerequisite for achieving an effective process design is to understand the customer requirements. Furthermore, to be an efficient design, the process input has to be considered, which implies an understanding of what the suppliers can offer. In order for the business strategy to be successful, the organization must be able to satisfy the requirements of the targeted customers in an efficient, competitive way.

Our discussion so far can be synthesized through the concept of strategic fit. Strategic fit refers to a match between the strategic or competitive position the organization wants to achieve in the external market, and the internal capabilities necessary to take it there. Another way of looking at this is to realize that strategic fit can by attained by a market-driven strategy or a process-driven strategy, or most commonly a combination of the two. In a market-driven strategy, the starting point is the key competitive priorities, meaning the strategic position the firm wants to reach. The organization then has to design and implement the necessary processes to support this position. In a process-driven strategy, the starting point is the available set of process capabilities. The organization then identifies a strategic position that is supported by these processes. This perspective illustrates that business process design is an important tool for linking the organization’s internal capabilities to the external environment so that the preferred business strategy can be realized.

1.4 Why Do Inefficient and Ineffective Business Processes Exist?

Throughout most of this chapter, we have been praising business process design and advocating the importance of well-designed processes. So, if businesses acknowledge this, then why were inefficient and ineffective (i.e., broken) processes designed in the first place? Hammer (1990), one of the founding fathers of the reengineering movement (discussed in Chapter 2), provided an insightful answer: Most of the processes and procedures seen in a business were not designed at all—they just happened. The following examples of this phenomenon are adapted from Hammer’s article.

Consider a company whose founder one day recognizes that she doesn’t have time to handle a chore, so she delegates it to Smith. Smith improvises. Time passes, the business grows, and Smith hires an entire staff to help him cope with the work volume. Most likely, they all improvise. Each day brings new challenges and special cases, and the staff adjusts its work accordingly. The potpourri of special cases and quick fixes is passed from one generation of workers to the next. This example illustrates what commonly occurs in many organizations; the ad hoc has been institutionalized and the temporary has been made permanent.

In another company, a new employee inquires: “Why do we send foreign accounts to the corner desk?” No one knew the answer until a company veteran explained that 20 years ago, an employee named Mary spoke French and Mary sat at the corner desk. Today, Mary is long gone and the company does not even do business in French-speaking countries, but foreign accounts are still sent to the corner desk.

An electronics company spends $10 million per year to manage a field inventory worth $20 million. Why? Once upon a time, the inventory was worth $200 million and the cost of managing it was $5 million. Since then, warehousing costs have escalated, components have become less expensive, and better forecasting techniques have minimized the number of units in inventory. The only thing that remains unchanged is the inventory management system.

Finally, consider the purchasing process of a company in which initially, the only employees are the original founders. Because the cofounders trust each other’s judgment with respect to purchases, the process consists of placing an order, waiting for the order to arrive, receiving the order, and verifying its contents (see “Original Purchasing Process” in Figure 1.8). When the company grows, the cofounders believe that they cannot afford to have the same level of trust with other employees in the company. Control mechanisms are installed to guarantee the legitimacy of the purchase orders. The process grows, but the number of value-adding activities (i.e., Ordering and Receiving) remains the same. (See “Evolved Purchasing Process” in Figure 1.8.)

Hammer introduced the notion of “information poverty” to explain the need for introducing activities that make existing processes inefficient. Many business processes originated before the advent of modern computer and telecommunications technology, and therefore they contain mechanisms designed to compensate for information poverty. Although companies today are information affluent, they still use the same old mechanisms and embed them in automated systems. Large inventories are excellent examples of a mechanism to deal with information poverty, which in this case means lack of knowledge with respect to demand. Information technology enables most operations to obtain point-of-sales data in real time that can be used to drastically reduce or virtually eliminate the need for inventories in many settings. Consequently, inefficient or ineffective processes can be the result of an organization's inability to take advantage of changes in the external and internal environments that have produced new design enablers such as information technology.

Another reason for the existence of inefficient process structures is the local adjustments made to deal with changes in the external and internal environments. When these incremental changes accumulate over time, they create inconsistent structures. Adjustments often are made to cope with new situations, but seldom does anyone ever question whether an established procedure is necessary.

In other words, inefficient and ineffective processes usually are not designed; they emerge as a consequence of uncoordinated incremental change or the inability to take advantage of new design enablers.

1.5 Summary

Business processes describe how things are done in a business and encompass all activities taking place in an organization including manufacturing processes, as well as service and administrative processes. A more precise definition useful for purposes of modeling and analysis is that a business process is “a network of connected activities with well-defined boundaries and precedence relationships that utilizes resources to transform inputs to outputs with the purpose of satisfying customer requirements.” Depending on the organizational scope, a business process can be categorized hierarchically as cross functional, functional, or individual; typically, the cross-functional processes offer the greatest potential for improvement.

The essence of business process design is to determine how to do things in an efficient and effective way. More formally, business process design can be described as a configuration of the process architecture, (i.e., the inputs and outputs, the flow units, the network of activities and buffers, the resources, and the information structure), so as to satisfy external and internal customer requirements in an efficient way. In this context, it is important that the requirements of the internal customers are aligned with the overall business goals, which ultimately boils down to satisfying the desires of the external customers targeted in the business strategy.

A linkage between overall business performance and business process design can be made through the fundamental need of any business, profit maximizing or not, to satisfy and thereby attract customers while maintaining an efficient use of resources. For a nonprofit organization, this is a necessity for survival because it enables the company to continue fulfilling its purpose. For profit-maximizing organizations, the ability to reach the overarching objective of generating long-term profits and returns above the cost of capital is contingent upon the firm’s long-term ability to maximize revenues and minimize costs. In the long run, this requires well-designed business processes. Similarly, in developing a business strategy, business process design is an important vehicle for linking the internal capabilities with the external opportunities. This allows the company to achieve a strategic fit between the firm’s desired competitive position in the external market and the internal capabilities necessary to reach and sustain this position.

Finally, in this chapter, we also illustrated the fact that the emergence of inefficient and ineffective processes is inherent to most organizations simply because they must adjust to changes in their internal and external environments. These incremental adjustments, which usually make good sense when they are introduced, at least locally, tend to accumulate with time and create inefficient structures. On the other hand, another common reason for inefficiencies is the inability to take advantage of new design enablers such as information technology and automating old work processes instead of using the new technology to do things in a more efficient way. This is why we have emphasized that inefficient and ineffective processes usually are not designed; they emerge as a consequence of uncoordinated incremental change or inability to take advantage of new design enablers.

1.6 References

Anupindi, R., S. Chopra, S. D. Deshmukh, J. A. Van Mieghem, and E. Zemel. 1999. Managing business process flows. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Cross, K.F., J.J. Feather, and R.L. Lynch. 1994. Corporate renaissance: The art of reengineering. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Business.

Davenport, T. 1993. Process innovation: Reengineering work through information technology. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Davenport, T, and J. Short. 1990. The new industrial engineering: Information technology and business process redesign. Sloan Management Review 31, 4 (Summer): 11-27.

Gabor, A. 1990. The man who discovered quality. New York: Penguin Books.

Goldsborough, R. 1998. PCs and the productivity paradox. ComputorEdge 16,43 (October 26): 23-24.

Grant, R. M. 1995. Contemporary strategy analysis. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

Grover, V., and M. J. Malhotra. 1997. Business process reengineering: A tutorial on the concept, evolution, method, technology, and application. Journal of Operations Management 15:193-213.

Hammer, M. 1990. Reengineering work: Don’t automate, obliterate. Harvard Business Review 71(6): 119-131.

Hammer, M., and J. Champy. 1993. Reengineering the corporation: A manifesto for business revolution. New York: Harper Business.

Harbour, J. L. 1994. The process reengineering workbook. New York: Quality Resources.

Lowenthal, J. N. 1994. Reengineering the organization: A step-by-step approach to corporate revitalization. Milwaukee, WL:ASQC Quality Press.

Manganelli, R. L., and M. M. Klein. 1994. A framework for reengineering. Management Review (June): American Management Association, 10-16.

Petrozzo, D. P., and J. C. Stepper. 1994. Successful reengineering. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Roberts, L. 1994. Process reengineering: A key to achieving breakthrough success. Milwaukee, WI: ASQC Quality Press.

Shafer, S. M., and J. R. Meredith. 1998. Operations management: A process approach with spreadsheets. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

Van Gigch, John P. 1978. Applied general systems theory. New York: Harper and Row Publishers.

1.7 Discussion Questions and Exercises

- Requisition Process (adapted from Harbour, 1994)—A large company is having trouble processing requisition forms for supplies and materials. Just getting through the initial approval process seems to take forever. Then, the order must be placed, and the supplies and materials must be received and delivered to the correct location. These delays usually cause only minor inconveniences. However, a lack of supplies and materials sometimes stops an entire operation. After one such instance, a senior manager has had enough. The manager wants to know the reason for the excessive delays. The manager also wants to know where to place blame for the problem!

A process analysis is done at the manager’s request. The requisition process is broken down into three subprocesses: (1) requisition form completion and authorization, (2) ordering, and (3) receiving and delivery. The process analysis also reveals that the first subprocess consists of the steps shown in Table 1.3.

TABLE 1.3 Steps in the Requisition Process

- Classify the activities in this process.

- Who is the customer?

- Translate what you think the customer wants into measures of process performance.

- How is the process performing under the measures defined in part (c)?

- Comment on the manager’s attitude.

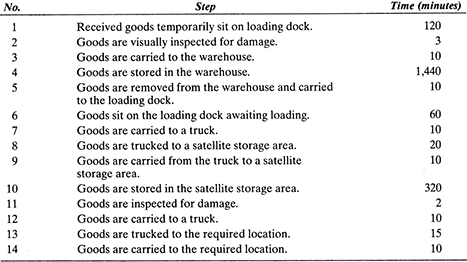

- Receiving and Delivery Process (adapted from Harbour, 1994)—The company in exercise 1 has a large manufacturing complex that is spread over a large area. You are assigned to study the receiving-and-delivery subprocess in order to make recommendations to the senior manager for streamlining the process. The subprocess begins with receiving goods on the warehouse loading dock, and it ends with the goods being delivered to the correct location. Before you were assigned to this project, the senior manager had a student intern do a simple process analysis. The manager instructed the student to observe the process and describe the various steps. Also, the student was told to find average processing times for each step in the process. The information collected by the student is summarized in Table 1.4.

- Classify the activities in this process.

- Who is the customer?

- Translate what you think the customer wants into measures of process performance.

- How is the process performing under the measures defined in part (c)?

- Comment on the instructions given to the intern by the senior manager in reference to the process analysis.

- Hospital Administrative Processes (adapted from Harbour, 1994)—A director of administration for a large hospital complex receives some disturbing news. A recent auditor’s report states that 28 percent of all hospital costs are related to administrative costs. The director is determined to lower this figure. She has read some magazine and newspaper articles about business process design and has decided to try it to see if it works. She calls a special off-site meeting. The meeting is held at a luxury hotel, and only senior-level managers are invited. At the meeting, she presents her concerns. She then states that the purpose of the meeting is to redesign the various administrative processes. A brainstorming session is conducted to identify potential problems. The problems are then prioritized. The meeting breaks for lunch.

After lunch, everyone works on developing some solutions. A number of high-level process maps are taped to the wall, and the director discusses each of the identified problems. One suggested solution is reorganization. Everyone loves the idea. Instead of 12 major divisions, it is suggested to reorganize into 10. After the meeting is over, the director spends 4 hours hammering out the details of the reorganization. She returns to work the next day and announces the reorganization plan. Sitting in her office, she reflects on her first process redesigning efforts. She is pleased.

- How would you rate the director’s redesign project? Would you give her a pay raise?

- How would you conduct this process redesigning effort?

- Environmental Computer Models (adapted from Harbour, 1994)—An environmental company specializes in developing computer models. The models display the direction of groundwater flow, and they are used to predict the movement of pollutants. The company’s major customers are state and federal agencies. The development of the computer models is a fairly complex process. First, numerous water wells are drilled in an area. Then probes are lowered into each well at various depths. From instruments attached to the probes, a number of recordings are made. Field technicians, who record the data on paper forms, do this. The data consist mostly of long lists of numbers. Back in the office, a data-entry clerk enters the numbers into a computer. The clerk typically enters hundreds of numbers at a time. The entered data are then used to develop the computer models.

Recently, the company has experienced numerous problems with data quality. Numerous data entry errors have resulted in the generation of inaccurate models. When this happens, someone must carefully review the entered data. When incorrect numbers are identified, they are reentered and another computer model is generated. This rework process often must be repeated more than once. Because it takes a long time to generate the models, such errors add considerable cost and time to a project. However, these additional costs cannot be passed on to the customer. Prices for the computer models are based on fixed bids, so the company must pay all rework costs. Alarmingly, rework costs have skyrocketed. On the last two jobs, such additional costs eliminated almost all profits. The company has decided to fix the problem. The company’s first step has been to hire an expert in data quality.

The consultant makes a series of random inspections. First, the consultant checks the original numbers recorded by the field technicians. They all seem correct. Next, the consultant examines the data entered by the data entry clerks. Numerous transposition errors are identified. Some of the errors are huge. For example, one error changed 1,927 to 9,127; another changed 1,898 to 8,198. The consultant proposes some process changes, including adding an inspection step after the computer data entry step. The consultant suggests that someone other than the data entry clerk should perform this inspection. Because each model has hundreds of numbers, the additional inspection step will take some time. However, the consultant can think of no other way to prevent the data entry errors. The proposed process is outlined in Table 1.5.

The consultant was paid and left for what he described as a “well-deserved vacation” in Hawaii. The company currently is hiring people to staff the third step in the process.

TABLE 1.5 Proposed Process for Environmental Computer Models

- What measures should be used to assess the performance of this process?

- How would the consultant’s proposed process perform according to the measures defined in part (a)?

- Do you agree with the consultant’s methodology and improvement strategies?

- Would you propose a different process?

- On June 3,2000, Toronto Pearson Airport implemented a new process to connect international flights (for example, those arriving from Europe) and United States-bound flights. The new process was described on Connection Information Cards that were made available to arriving passengers. The card outlined the following nine steps for an “easy and worry-free connection”:

- Complete Canadian and U.S. forms during the flight.

- Proceed through Canada Immigration/Customs.

- Follow signage upstairs to Baggage Claim and pick up your bags.

- Hand Canada customs card to the customs officer; follow sign for connecting customers.

- Proceed to the connecting baggage drop-off belt and place your bags on the belt.

- A frequent shuttle bus to Terminal 2 leaves from the departure level (upstairs).

- Disembark at U.S. Departures; proceed to the carousel behind U.S. check-in counters (“Connecting to U.S.A.”) and pick up your bags.

- Proceed through U.S. Customs and Immigration.

- Leave your bags on the baggage belt before going through security to your gate. Construct a list of activities and include all non-value-adding activities associated with waiting (e.g., waiting for luggage, waiting for an immigration officer, waiting for a shuttle). Estimate the percentage of time passengers spend on value-adding activities versus the time spent on non-value-adding activities. Identify potential sources of errors or additional delays that can result in a hassle to the passengers. Do you expect this process to deliver on the promise of an “easy and worry-free connection”?

- A city council hires a consultant to help redesign the building permit process of the city. After gaining an understanding of the current process, the consultant suggests that the best solution is to create a one-size-fits-all process to handle all building-related applications. What is your opinion about the consultant’s solution?