Chapter 3. Scrum

In 1990, I was a member of the team developing the avionics test bed for an experimental fighter jet called the YF-23. This work required me to stay at a McDonnell Douglas facility in St. Louis, Missouri, for almost a year. Members of the team had gathered from all around the company to prepare the avionics for demonstration to the Air Force. We faced many imposing challenges—most caused because the various components of hardware and software had been separately developed, and they were resisting integration. The avionics were designed to survive destruction of up to half of their components and still perform their function. Unfortunately, the actual hardware could barely tolerate being installed. One key component, a fiber-optic communication interface, was so sensitive that 29 out of 30 initial boards produced failed before our final demonstration!

The team was led by a former F-14 pilot. He was an outstanding leader who didn’t need to understand every detail of how each of us did our jobs. What he excelled at was removing obstacles from our paths.

We were guaranteed to see him every morning at the daily stand-up meeting. Scrum was largely unknown to the world in 1990, but F-14 pilots knew how to have a stand-up meeting. Each of us, in turn, told of our progress, what we were working on next, and what problems we were having.

Our pilot-lead had an interesting habit that I will never forget: He always trimmed his nails during this meeting. He focused on his nail clipper, but we knew he was listening. I didn’t realize it at the time, but my inability to make eye contact with him forced me to speak to the group instead. If a discussion got too involved, he cut it short.

One day I reported that the McDonnell Douglas system administrator was not giving us access to a computer that he had promised to a week earlier. It was cutting into our efforts to test the avionics, and the administrator was being rude to the contractors. As soon as I said it, our lead’s head snapped up. With a steady, steely glare he repeated what he heard me say. I verified that he had heard me right; the administrator was messing with his team.

Five minutes after the conclusion of the meeting, we heard our lead swearing at the top of his lungs at the administrator. They must have a class for F-14 pilots on the creative application of profanity. It was impressive to hear. It was even more impressive to realize that our pilot-lead had our back. He was our “wingman,” and as Tom Cruise’s character learned in Top Gun, you never leave your wingman.

We received access immediately and never had another problem with the administrator. It was a pivotal moment for the team. We had started the day as a collection of contractors from around the country. By noon, we were the team you didn’t mess with. Did it affect our work? You bet. We didn’t have any excuses not to solve our own problems with the dedication demonstrated by our lead.

Our lead demonstrated many of the values and practices of Scrum long before any of us had heard of it. Was he prescient? No, he was merely applying good practices known to many good leaders. Scrum does the same thing. Its practices derive from those who have worked in many high-performing organizations or teams for decades.

Scrum is a framework for creating complex products. It’s not a process or a methodology; its practices aren’t specific enough to tell programmers, artists, designers, producers, QA, and so on, how to do their jobs. A studio adopting Scrum merges its own practices into the Scrum framework to form its own methodology.

Scrum compels a studio to create an incremental and iterative development process with self-managing, cross-disciplined teams. The rules of Scrum are simple, but from these simple rules emerge vast improvements in how teams work together. They increase their productivity and enjoy their work more. It’s like chess; from the simple rules of chess emerge complex tactics and strategy that take a lifetime to master. Scrum is also a never-ending pursuit for continual improvement, especially in the rapidly changing game development industry.

This chapter introduces Scrum. First, we have a rundown of Scrum and look at some of its components and practices in more detail. Next, we examine the various roles involved with Scrum. We finish up discussing customers and stakeholders and how Scrum scales.

The History of Scrum

Product development methods—from the industrial revolution through the information age—have undergone a slow evolution. It’s an evolution of how people work together to create products.

The industrial revolution arose from the limitations of craftsmanship. The limited supply of craftspeople kept the supply of products low and their cost high. The assembly line transferred product creation to workers on the assembly line who were considered replaceable cogs performing only simple tasks. It removed the value of knowledge at every stage to a centralized few called managers.

With the introduction of the assembly line, everyone could afford a product like the Model T car. The cost in doing this was the loss of customization and variety that the craftsperson supplied.1

1 Henry Ford’s famous quote “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black” highlights this lack of variety of choice.

The weakness of Henry Ford’s assembly line, which was optimized by Taylor (1911), was that it didn’t leverage the knowledge and creativity of the people on the assembly line. Working in a factory became synonymous with the loss of humanity to the large machine of society that seemed to be emerging.2

2 Read Orwell’s novel 1984 to get a sense of this attitude toward the future.

Two world wars created demand for large amounts of material from a limited workforce. This drove innovation at the factory level. Millions of “Rosie the Riveters” had to be trained and made productive. This required more than mindless assembly-line workers. Leadership was required to train and guide this new workforce. Knowledge and skill at every level of the assembly line became recognized as a critical asset as valuable as the capital equipment in the factories themselves.

As the war ended, the soldiers returned to their jobs, and America found itself with the only intact industrial base. This led to a languid attitude toward the wartime lessons, many of which were forgotten in the factories. Additionally, the people who filled the roles in the factories of the departed soldiers (the “Rosie the Riveters” of America) left the factories and took much of the new knowledge tools with them.

Overseas the lessons were embraced. For example, as America occupied Japan, many of the industrial consultants who helped American industry ramp up production during the war were brought over to help Japan rebuild its devastated manufacturing industries. Companies such as Toyota merged some of these principles with their own. These companies were able to elevate productivity as American industry had done during the war.

These changes in Japan continued to restore the value of individuals in the workplace and decentralize many of the day-to-day decisions about quality and efficiency. As a result, Toyota, and companies like it, has leveraged the lower cost and higher quality of its products to dominate the world automobile market.

In the mid-eighties, the differences in product development were researched and described in a groundbreaking article titled “The new new product development game” (Takeuchi and Nonaka 1986). This study described how some companies consistently and rapidly released new highly successful and innovative products into the market. What made these companies different was their process for developing products.

These companies didn’t develop products using a traditional “relay-race” model of sequential development, such as the waterfall approach in the software industry. Instead, handpicked cross-discipline teams collaboratively iterated on the development of their products to a much higher degree. This approach to development was compared to the scrum formation of rugby teams that move the ball up and down the field together.

Scrum was first identified as a model for software development in the book Wicked Problems, Righteous Solutions (DeGrace and Stahl, 1990). This model was first applied at the Easel Corporation in the early nineties by Jeff Sutherland (2004) and Ken Schwaber at Advanced Development Methods. Then, Ken Schwaber and Mike Beedle (2002) teamed up to write a book, which popularized Scrum to a broad audience.

Although Sutherland and Schwaber were the first to use and define Scrum, Scrum integrates ideas from many sources. Teams meeting daily, owning the problem, putting the work to be done on a wall, and graphing the amount of work to be done are not novel ideas. What was novel about the earliest Scrum implementations was putting all of these ideas together.

The Big Picture

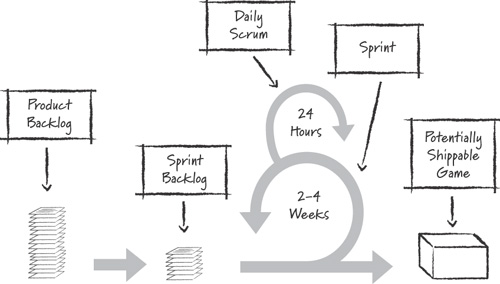

Figure 3.1 shows the major components of Scrum.

Figure 3.1. The big picture

Source: Mountain Goat Software

A game developed with Scrum makes progress in two- to four-week iterations, or sprints, using cross-discipline teams of six to ten people. At the start of a sprint, during the sprint planning meeting, the team selects a number of features from a prioritized list of them called the product backlog. Each feature on the product backlog is called a product backlog item (PBI). The team then estimates the tasks required to implement each PBI into a sprint backlog. Figure 3.2 shows a simple player jump feature and a sprint backlog of tasks to implement it.

Figure 3.2. An example of breaking a PBI into tasks for the sprint backlog

The team only commits to features in a sprint that they judge to be achievable.

The team meets daily during the sprint in a 15-minute timeboxed meeting called the daily scrum. During this meeting, they share their progress and any impediments to their work.

Definition

A timebox is a fixed amount of time given to a meeting, task, or work. This sets a limit on the amount of time spent. For example, a 15-minute timeboxed meeting will end at the 15-minute mark regardless of whether all the agenda items are addressed.

By the end of the sprint, the team has created a potentially shippable version of the game: a playable game, which won’t necessarily pass all the tests necessary to ship. The stakeholders (managers, directors, and publisher staff) of the game gather in a sprint review meeting to evaluate whether the goals of the sprint were met and to update the product backlog for the next sprint based on what they’ve learned.

One other practice is the sprint retrospective. This is a brief meeting held by the team following the sprint review to reflect on how effectively the team worked together over the last sprint and to find ways of improving their practices.

Note

Think of a potentially shippable version of the game as something you could run an informal focus test with.

The Principles of Scrum

Scrum has a small number of simple practices that teams can use to develop games. These practices are not all-encompassing or perfect for every product. As a framework, Scrum is meant to have practices added and changed as teams and products evolve.

It is important to preserve the principles of Scrum:

• Empiricism: Scrum uses an “inspect and adapt” cycle that enables the team and stakeholders to respond to emerging knowledge and changing conditions in real time using actual data. An example of this can be seen in the daily scrum practice, which enables the team to react to daily issues.

• Emergence: As we develop a game, we learn more about what makes it fun, what is possible, and how to create it. Scrum practices don’t ban designs from being developed up front. They acknowledge that we can’t know everything about a game from the start. The sprint review and planning cycle is designed to maximize emergence of features as seen in a working game.

• Timeboxing: Scrum is iterative. It delivers value on a regular basis and enables stakeholders and developers to synchronize and micro-steer the project as value emerges. Sprints are an example of a timeboxed practice.

• Prioritization: Some features are more important to the stakeholders than others. Rather than approaching the development of a game by “implementing everything in the design document,” Scrum projects develop features for a game based on their value to the player who will buy the game. The product backlog is an expression of this principle.

• Self-organization: Small, cross-discipline teams are empowered to organize their membership, manage their process, and create the best possible product within the timeboxes. They use the “inspect and adapt” cycle to continually improve how they work together, often through the sprint retrospective meeting.

By preserving these principles, Scrum teams can alter their practices and improve the benefits of Scrum.

Scrum Parts

In this section we look at some of the parts of Scrum identified in Figure 3.1 in detail as well as some additional practices.

The Product Backlog

The product backlog is a prioritized list of the requirements or features (called PBIs) for a game, a tool set, or the pipeline for making the game.

The following are examples of these requirements:

• Add a filtering function to the animation exporter.

• Add a particle effect to the game.

• Add online gameplay.

The product backlog is allowed to change after a sprint. PBIs that weren’t anticipated are added. PBIs that are no longer necessary are removed, and the priorities are changed as necessary.

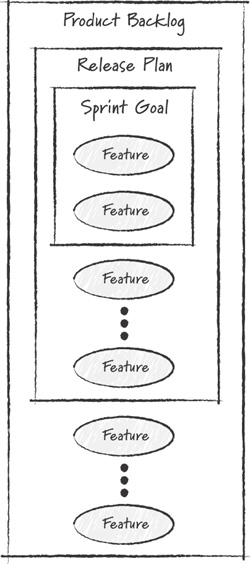

The value of each feature to the player is used to prioritize the backlog. The product backlog is not meant to be a detailed list of every feature we may need; that makes it too cumbersome to manipulate. Instead, the PBIs on the top of the list—in other words, the PBIs of highest value—are disaggregated, or broken down into small enough features for the team to work on over one sprint. Figure 3.3 demonstrates some PBIs for an example platform game.

Figure 3.3. A backlog of features/PBIs

Jump, crawl, and fly are the most valuable PBIs to implement right now and are at the top of the list. These PBIs are small enough to complete in a single sprint. PBIs such as online or in-game map editor are lower priority and are not dis-aggregated into smaller PBIs until the team is closer to implementing them.

Sprints

A Scrum-developed project makes progress in sprints. These iterations are the heartbeat of the project.

Sprints have a fixed duration (timebox) of two to four weeks. Teams commit to PBIs they can complete within the sprint. The overall objective of the sprint is called the sprint goal. A sprint goal is the overall theme of the sprint to which the team commits.

The sprint goal remains unchanged. At the end of the sprint, the team shows a new version of the game to the stakeholders, such as the publisher, which demonstrates the sprint goal.

Definition

A stakeholder is someone who has a stake in the outcome of the game project. These include people on the publishing side, other members of the project, and studio management.

Sprints produce vertical slices of functionality; they are like mini-projects themselves. A sprint contains design, coding, asset creation, tuning, debugging, and optimization—everything necessary to produce a potentially shippable game.

Many features require multiple sprints to develop. Sprints still need to demonstrate value at every review. Sometimes the customer wants to see some of the uncertainty or risk removed from the project as early as possible. Take, for example, a team delivering AI features: One of the most difficult challenges of AI behavior is navigation in a complex environment. The AI system has to identify obstacles that prevent an AI character from moving and calculate a path around them. With the addition of moving characters and objects, the problem can become intractable. Navigation is one the riskiest problems to solve for the entire game.

We want to solve the navigation problem as early as possible. Other related systems—such as character animation and physics—might not be mature enough to support the sprint goal of having a polished AI character walk through a complex environment. In this case, a sprint goal for the team could be to demonstrate simple capsules navigating a complex test environment. This goal doesn’t demonstrate a complete feature, but it does represent value in reducing risk.

Does this remove all the risk associated with AI characters navigating complex environments? No. It addresses a big part of the problem. There still may be other problems that crop up when progress is made with the animation and physics. We want to minimize work built on assumptions. For example, the next sprint goal for the AI team could be to demonstrate the test capsule “climbing” stairs. Discovering that AI characters can’t climb stairs during production could be a disaster if a number of levels and animations were built assuming it worked.

Releases

Releases are a set of sprints meant to bring a game with major new features to a near-shippable state. A typical release lasts between two to four months. The pace of releases is similar to those of milestones on a typical project.

Near-shippable state means “playable by potential buyers of the game but not necessarily ready to package with full content or pass all first-party requirements tests.” On a two-year project, releases leading up to the shipped game should have a “magazine on downloadable demo quality.” Games ship following the release that ensure first-party hardware (technical certification requirement [TCR] or technical requirements checklist [TRC]) or broad hardware compatibility tests are completed.

Releases establish longer-term goals for the team and stakeholders. They require an elevated level of polish and debugging that reduces a great deal of uncertainty about the work left to do to ship the game.

Releases start with a planning session that establishes major goals for the game. A release plan drives the goals for each sprint. Figure 3.4 shows how the release plan is a subset of features from the product backlog and how each sprint goal is a subset of the release plan.

Figure 3.4. Subsets of planning

Scrum Roles

Scrum gains much of its benefit from sprints and teams that make commitments to goals and own their work. There is a distinct separation in the roles and responsibilities between Scrum teams and the customers. Scrum teams and customers agree on goals, which satisfy clearly defined needs of the customer. Figure 3.5 shows the various roles described in this section.

Figure 3.5. The Scrum roles

The Scrum Team

A Scrum team consists of a ScrumMaster, a product owner, and a team of developers.

The ScrumMaster is responsible for educating the team about Scrum, ensuring the members follow the practices established for themselves. The ScrumMaster facilitates problem solving and runs interference for the team against the chickens (or invading pirates) when necessary (see the section “Chickens and Pigs” and the sidebar “Renaming Chickens and Pigs”). This was what our F-14 pilot did for us.

The product owner is responsible for communicating the vision of the game and maximizing the return on investment (ROI). The product owner maximizes ROI by establishing and prioritizing the desirable features in the product backlog.

The team delivers sets of features from the product backlog every sprint. Developers are self-organizing and self-managing; they determine how much work they can commit to at the start of a sprint and take responsibility to deliver the completed work by the end.

In coming sections, we’ll cover the roles on a project that uses Scrum.

The Team

The team includes everyone from every discipline necessary to complete the goals that the team commits to for a sprint. For example, a team committing to a goal that required a walking, talking AI character should have animators, AI programmers, character modelers, and even QA to help the team ensure that the goal is done.

Note

The term teams often refers to everyone on a project. In the book, we’ll call that group the project staff. Therefore, a project staff of eighty people might contain seven to nine teams.

Terminology

There has been a lot of debate about these terms in the Scrum community. The community has settled on these terms for the benefit of consistency. Personally I prefer calling the team the developers to avoid multiple uses of the word team in the official definitions, but I’ll stick with calling them the team for the book.

ScrumMaster

The ScrumMaster role is pivotal for the success of Scrum, yet it is the most misunderstood role. It is neither a traditional lead nor a management role. The ScrumMaster improves the use of Scrum through coaching, facilitation, and the rapid elimination of anything that distracts the team from delivering value.

Responsibilities

The job of the ScrumMaster is to ensure that Scrum is a success. The ScrumMaster must apply the principles of Scrum and deftly guide the team through the practices.

When a team starts using Scrum, they should rigorously apply a subset of Scrum practices “by the book.” Over time, those practices gradually change as the team finds better ways of working together. The ScrumMaster’s role is to ensure that the principles behind Scrum remain intact and that the team sticks to the practices they agree to follow.

The ScrumMaster is the conscience of the team in a sense; the principles of Scrum are inconvenient at times. For example, a team may be ignoring bugs or unpolished assets in their rush to deliver on a sprint. The ScrumMaster must remind them that each sprint delivers a vertical slice of the game and must not defer bug fixing or asset polishing to a future sprint.

One of the main responsibilities of the ScrumMaster is to nurture the sense of ownership within the team. Ownership has great value (see the sidebar “Ownership”). The ScrumMaster knows when to let teams occasionally falter and when to lend support. Much like a good parent, the ScrumMaster knows that protecting the team too much does not lead to growth and independence of thought and action.

The specific responsibilities of the ScrumMaster are as follows:

• Ensures impediments are addressed

• Monitors progress

• Facilitates planning, reviews, and retrospectives

• Encourages continual improvement

• Helps stakeholders and teams communicate

Ensures Impediments Are Addressed

There is seldom a single event that causes a project to be late; there are usually many hundreds or thousands of problems. Losing just a couple of hours a day can extend the time required to finish a one-year project by several months!

Scrum refers to every problem that interferes with progress as an impediment. Impediments take various forms:

• Bugs that crash the game or tools

• Excessive or long meetings that don’t produce results

• Constant distractions or interruptions from, for example, a frequently used intercom system

• Waiting for someone to finish something you need to make progress on your task

The list goes on. Scrum focuses the team on solving many of these impediments through the creation of cross-discipline teams and the daily scrum. A programmer who needs a test asset can turn to a team artist for help. A designer who shares the same sprint goal with a programmer finds that the programmer is easily motivated to help them solve a bug.

A cross-discipline team will rapidly solve most impediments identified throughout the day on their own. The ScrumMaster’s role is to ensure that visibility of impediments is raised to the proper level so they are addressed.

Some impediments cannot be solved by the team. For example, if an animator needs a tool purchased, the team probably does not have the authority to issue a purchase order directly. Much like my former F-14 boss did, the ScrumMaster takes ownership of this problem and raises it to the necessary level for the purchase to be authorized. Without this daily support, the tool purchase could take weeks to resolve.

Sometimes impediments take time to be resolved. The ScrumMaster tracks these to ensure that they are not forgotten.

Monitors Progress

The ScrumMaster ensures that the team remains aware of how well they are performing against their goal. A Scrum team monitors its progress every day and projects progress against the goal. If the team is slipping behind, they must be aware of it as soon as possible.

Facilitates Planning, Reviews, and Retrospectives

The ScrumMaster ensures that all team meetings are prepared for and facilitated. Facilitating a meeting includes scheduling the time, preparing the space, and ensuring that the meeting occurs within the time limits to which everyone agreed.

Ensuring that a meeting runs well is a deep skill that ScrumMasters need to continually develop and help teams learn to execute well on their own.

Encourages Continual Improvement

The ScrumMaster encourages the team to seek ways to improve their performance as a team. This never ceases. Even with the most productive teams, the ScrumMaster encourages them to seek even a single percentage point of improvement. This promotes a culture of continuous improvement. Improvements could be as simple as moving desks closer to improve communication or as hard as requesting new technology that improves the efficiency of the production pipeline.

The ScrumMaster role is mainly a facilitative one. The ScrumMaster might recognize problems before the team and identify a favored solution, but they should never lead by implementing the solution. Instead, a ScrumMaster will help a team recognize problems and own the solution. This teaches them the invaluable skill of identifying and solving problems on their own. In many ways, the role of the ScrumMaster is to coach the team to eliminate the need for a ScrumMaster.

Helps Stakeholders and Teams Communicate

Stakeholders and development teams speak different languages. Stakeholders speak about return on investment, profit/loss calculations, sales projections, and budgets. Development teams talk about technology, gameplay, and artistic vision. This divide of language prevents real communication from occurring between the two groups. It’s the job of the ScrumMaster to facilitate this communication, primarily through teaching the team the necessary amount of business language and focusing much of the communication bandwidth through the product backlog.

Attributes

A ScrumMaster’s role on the team is compared to a sheepdog. They guide the team toward the goal by enforcing boundaries, chasing off predators, and giving the occasional bark. The role of a ScrumMaster requires a proper attitude. An overbearing sheepdog stresses out the flock. A passive sheepdog lets the predators in among them.

The ScrumMaster trusts the team. The ScrumMaster guides the team to do their best work through coaching and facilitation. The ScrumMaster role is not easy, but it is rewarding. A ScrumMaster has to be stubborn and persistent. Many issues facing a team require intervention at a personal level with people who may not want to change their behaviors. For example, take a manager of considerable authority and many years of experience in a command and control environment who does not believe self-organization works. This manager repeatedly interferes with a team in ways that distract the team by assigning new work in the middle of a sprint. The ScrumMaster needs to persistently remind the manager about the purpose of Scrum and the reciprocal commitments between the team and the stakeholders. This needs to be done in a way that does not offend and raise barriers. It’s a coaching role. Not everyone can do it.

There is a formal course meant to introduce Scrum. This “Certified ScrumMaster Training Course” is an immersion in the practices and principles of Scrum given by a Scrum trainer who is certified by the Scrum Alliance.3,4

4 I also provide a Certified ScrumMaster (CSM) class specifically tailored for game development. Visit www.ClintonKeith.com for more details.

This course is highly recommended for anyone new to Scrum, and it will also benefit members of an experienced team by reinforcing the principles and practices of Scrum.

Wearing the ScrumMaster Hat

Sometimes when a developer on the team takes on the role of the ScrumMaster, they carry a hat around with them. They don the hat when they are in the ScrumMaster role and take it off when they are in the developer role. It helps the team know who is speaking to them.

Product Owner

The product owner establishes and communicates the vision of the game and prioritizes its features.

The product owner is responsible for the following:

• Managing the ROI for the game

• Establishing a shared vision for the game among the customers and developers

• Knowing what to build and in what order

• Creating release plans and establishing delivery dates

• Supporting sprint planning and reviews

• Representing the customers, including the player who buys the game

Most video game projects have one true release to get things right. Most of our games can’t slowly grow their feature sets and a market simultaneously like other products. This requires great vision; it makes the role of a product owner on an agile video game project critical.

Manages the ROI

The product owner is responsible for ensuring that the investment in the game is returned with a profit. This requires the product owner to know what the market wants, even years in advance of the release.

The product owner is responsible for other metrics of a project’s success. These include the performance of the game on the target platforms, the final cost of the game, and the ship date. Forecasts, such as average game rankings and profit/loss (P&L) calculations, can be applied, but these are marketing projections that can’t guide projects very well. The product owner creates a bridge between marketing, sales, and the Scrum team by demonstrating the emerging game and collaborating on the direction the game is heading.

Creates a Shared Vision

The product owner is a single voice for the vision that is shared with the team. They ignite creativity and ownership with the team and collaborate with them as the vision evolves with the emerging game.

Having a shared vision is critical for the success of any game. Lacking vision, a large team of developers will go off in separate directions, creating a Frankenstein game of parts that don’t mesh. We’ve all seen these games—the ones that have beautiful art but no great gameplay, the games that have a great mechanic but too many performance problems to be playable, or the games that have dozens of mechanics but not one of them done well.

Sharing a project vision is not easy. It was easier when a game had a few less-specialized developers, but many games being developed today require a small army of specialists. Large development teams allow people to become isolated by discipline. This isolation creates further barriers to a shared vision; programmers sitting together start to see a game project as a computer science project. Artists produce art that satisfy other artists. Designers create baroque control schemes that only other designers can appreciate. Each group focuses on the challenges for their own discipline and loses sight of the business side.

The product owner’s role in creating the vision for a video game project is comparable to the role played by key visionaries such as Shigeru Miyamoto,5 Will Wright,6 Tim Schafer,7 Warren Spector,8 and Sid Meier9 on their projects. A product owner represents the ultimate customer during development: the player. The product owner has to foresee what the market will embrace up to three years in advance. They have to know the mind and emotional responses of the player.

5 Creator of Donkey Kong, Mario, Zelda, and so on

6 Creator of The Sims and Spore

7 Creator of Full Throttle and Physchonauts

8 Creator of Deus Ex

9 Creator of the Civilization series

Owns the Product Backlog

The product owner owns the product backlog and determines the order of features on the backlog. This order reflects the order of when those features are developed.

The product owner usually cannot manage a product backlog alone. The backlog may have features that require a technical, artistic, or design understanding to create or prioritize. Some features support the efforts of sales and marketing to help promote the game, such as in-game advertisements. The product owner needs to work with the various customers and stakeholders of the game to understand all of their needs.

Manages Releases

The product owner manages the releases and calls for release plans and the delivery date. The product owner revises the release plan based on changes to the goals or the progress from the teams during sprints. The product owner guides the various release activities. We’ll cover these activities in more detail in Chapter 6.

Sprint Planning and Review

The product owner has the following major duties during a sprint:

• Establishing and updating the features on the backlog and their priorities

• Participating in sprint planning

• Participating in the sprint review and accepting or rejecting the results of the sprints

Figure 3.6 summarizes the role of the product owner regarding the product backlog and sprints.

Figure 3.6. The product owner role

Customers and Stakeholders

The relationship of customers and stakeholders to the Scrum team is important. They define many of the items on the backlog. They work with the product owner to help prioritize the backlog. Although the product owner is a member of a Scrum team, the product owner is considered the “lead customer.” This person determines the priority of features on the backlog. The product owner provides a service to the team by being the one voice of all the customers and stakeholders.

The ultimate customer is the player who will buy the game. Although the player doesn’t directly define the requirements of the game, all stakeholders represent them. The stakeholders are people outside the team that have a stake in the game being made.

The following are some common stakeholder roles:

• Publisher-producer: The publisher-producer communicates the progress and goals between publisher and the studio. One of the main values of this role is to ensure that both sides have the same vision about the game and that there is transparency about the progress of a game.

• Marketing: Marketing provides input on the relative importance of features in the backlog and, by understanding the backlog, more effectively communicates the key features of the game to the market.

• Studio leadership: Studio art, design, and technology leadership help the product owner prioritize work, especially with respect to cost and risk of feature development. For example, as a former chief technical officer, my role was to work with the product owner and the project staff to address areas of technical risk through the product backlog.

Each of these stakeholders can introduce feature requests to the product backlog. For example, when I was a CTO, I was mostly concerned with the technical risk in implementing various features in the game and the pipeline. As a result, I introduced requirements that helped the team gain knowledge about risk or helped everyone understand the cost of implementing a feature.

Note

Many agile books will combine the roles of stakeholders and customers into the customer role. However, with many games taking years to develop that are externally financed, the distinction is important to game developers. Stakeholders are the proxies for the true customers who do not have a voice to communicate their wants and needs about the game every sprint.

Chickens and Pigs

A book describing Scrum can’t avoid telling the story about “the pig and the chicken,” so here goes:

Once upon a time, a pig and chicken were talking. “I have an idea,” the chicken exclaimed, “let’s open a restaurant; we’ll call it Ham and Eggs.” The pig thought about it for a moment and said, “No thanks...you’d only be involved, but I’d be committed.”

This is how the labels of pigs and chickens got their start (see the sidebar “Renaming Pigs and Chickens”). Pigs are the members of a Scrum team who commit to the work in the sprint. Chickens are the customers and stakeholders outside the team who do not make the personal commitment to the work.

Chickens influence the direction of the project between sprints. Chickens and pigs discuss the goals of an upcoming sprint and prioritize the product backlog. The pigs (teams) commit to implementing features. The chickens commit to allowing the team to achieve those goals without interference. This reciprocal commitment between the pigs and chickens enables Scrum to work. If the chickens are allowed to change a sprint goal, then it is not possible for the pigs to truly commit to it at the start of the sprint.

Scaling Scrum

Scrum teams have less than a dozen developers, but most game projects require more developers to create. Scrum supports these larger teams through scaling. This is done by having a num ber of Scrum teams work in parallel and coordinating their work through practices such as the scrum of scrums, which the book will address in great detail in Chapter 8, “Teams.”

Summary

Scrum practices and roles are simple and easy to start using. So, why read an entire book dedicated to using agile practices, such as Scrum, for game development? The reason is that the practices previously described are only a starting point.

Scrum creates the opportunity for you to measure and question every practice you use to make games (inspect) and enables you to introduce change to improve them (adapt). Scrum gives you empirical tools to measure the effectiveness of your team. These measurements give you feedback about the benefits and drawbacks of every change and enable you to enter the endless cycle of continually improving your practices. The challenge in adopting Scrum is to learn how and why it works and then modify your practices to leverage the transparency that Scrum creates.

The next chapter rounds out the basics of Scrum by detailing the activities involved in sprints. The remainder of the book addresses how game developers inspect and adapt the basic practices for developing their games.

Additional Reading

Schwaber, K. 2004. Agile Project Management with Scrum. Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press.

Takeuchi, H., Nonaka, I. 1986. The new new product development game, Harvard Business Review, pp. 137-146, January-February.