Chapter 2: Fighting Viri and Scum

In This Chapter

![]() Quick security checklist — do’s and don’ts

Quick security checklist — do’s and don’ts

![]() Getting the lowdown on malware

Getting the lowdown on malware

![]() Understanding how Windows Defender works

Understanding how Windows Defender works

![]() Scanning for rootkits via Windows Defender Offline

Scanning for rootkits via Windows Defender Offline

![]() Deciphering your browser’s cryptic security signs

Deciphering your browser’s cryptic security signs

Windows 8 was the first version of Windows to ship with a complete antivirus/anti-spy/anti-malware package baked right into the product. Windows 8.1 brings along all those goodies.

On the other hand, you need to hold up your end of the bargain by not doing anything, uh, questionable. I wanted to say “stupid” but some of the tricks the scummeisters use these days can get you even if you aren’t stupid. Book IX, Chapter 1 helps you understand the tactics online creeps use and keep your guard up.

I start this chapter with a very simple list of do’s and don’ts for protecting your computer and your identity. They’re important. Even if you don’t read the rest of this chapter, make sure you read — and understand, and follow — the rules in each list.

Basic Windows Security Do’s and Don’ts

![]() Check daily to make sure Windows Defender is running. If something’s amiss, a red “X” appears on the Action Center flag, down in the desktop’s notification area, near the time. To check Defender’s status, on the Start screen, type def and choose Windows Defender. If Defender’s running, a green check mark appears, as shown in Figure 2-1.

Check daily to make sure Windows Defender is running. If something’s amiss, a red “X” appears on the Action Center flag, down in the desktop’s notification area, near the time. To check Defender’s status, on the Start screen, type def and choose Windows Defender. If Defender’s running, a green check mark appears, as shown in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1: Windows Defender is up and running.

Actually, Windows should tell you if Defender stops, either via a toaster notification from the right side or a red X on the flag in the lower-right corner of the desktop. But if you want to be absolutely sure, there’s no better way than to check it yourself. Only takes a second.

![]() Don’t use just any old browser. Internet Explorer is getting better, but I usually run Chrome (realizing that Google keeps track of where I’m going, all the better to serve me ads) because Chrome has superior Java and Flash support built-in. I switch to Firefox from time to time, but I use it with NoScript or a similar Java and Flash blocker installed and working.

Don’t use just any old browser. Internet Explorer is getting better, but I usually run Chrome (realizing that Google keeps track of where I’m going, all the better to serve me ads) because Chrome has superior Java and Flash support built-in. I switch to Firefox from time to time, but I use it with NoScript or a similar Java and Flash blocker installed and working.

Most Windows infections come in the door through Java, Flash, or Adobe Reader (see Book IX, Chapter 1).

![]() Use anything other than Adobe Reader to look at PDF files.

Use anything other than Adobe Reader to look at PDF files.

All the major browsers are gradually getting their own PDF readers, just because Adobe Reader has caused so many infections.

![]() Every month or so, run Windows Defender Offline. WDO scans for rootkits. I talk about WDO later in this chapter.

Every month or so, run Windows Defender Offline. WDO scans for rootkits. I talk about WDO later in this chapter.

![]() Every month or so, run Malwarebytes. The Malwarebytes program gives you a second opinion, possibly pointing out questionable programs that Windows Defender doesn’t flag. I talk about Malwarebytes in Book IX, Chapter 4.

Every month or so, run Malwarebytes. The Malwarebytes program gives you a second opinion, possibly pointing out questionable programs that Windows Defender doesn’t flag. I talk about Malwarebytes in Book IX, Chapter 4.

![]() Delete chain mail.

Delete chain mail.

I’m sure that you’ll be bringing down the wrath of several lesser deities for the rest of your days, but do everyone a favor and don’t forward junk. Please.

I’m sure that you’ll be bringing down the wrath of several lesser deities for the rest of your days, but do everyone a favor and don’t forward junk. Please.

If something you receive in an e-mail sounds really, really cool, it's probably fake — an urban legend or a come-on of some sort. Look it up at www.snopes.com.

![]() Keep up to date with Windows patches and (especially) patches to other programs running on your computer. See my diatribe about Windows Automatic Update in Book VIII, Chapter 3. For help keeping your other programs updated, use Secunia Personal Software Inspector, which I describe in Book IX, Chapter 4.

Keep up to date with Windows patches and (especially) patches to other programs running on your computer. See my diatribe about Windows Automatic Update in Book VIII, Chapter 3. For help keeping your other programs updated, use Secunia Personal Software Inspector, which I describe in Book IX, Chapter 4.

![]() Check your credit cards and bank balances regularly.

Check your credit cards and bank balances regularly.

I check my charges and balances every couple of days and suggest you do the same.

I check my charges and balances every couple of days and suggest you do the same.

![]() If you don’t need a program any more, get rid of it. Use the Windows Uninstaller that I describe in Book VII, Chapter 1. If it doesn’t blast away easily, use Revo Uninstaller in Book X, Chapter 5.

If you don’t need a program any more, get rid of it. Use the Windows Uninstaller that I describe in Book VII, Chapter 1. If it doesn’t blast away easily, use Revo Uninstaller in Book X, Chapter 5.

![]() Change your passwords regularly. Yeah, another one of those things everybody recommends, but nobody does. Except you really should. See the admonitions in Book II, Chapter 4 about choosing good passwords, but especially take a look at LastPass and RoboForm, which I describe in Book IX, Chapter 4.

Change your passwords regularly. Yeah, another one of those things everybody recommends, but nobody does. Except you really should. See the admonitions in Book II, Chapter 4 about choosing good passwords, but especially take a look at LastPass and RoboForm, which I describe in Book IX, Chapter 4.

Here are the ten most important things you shouldn’t do, to keep your computer secure:

![]() Don’t trust any PC unless you, personally, have been taking close care of it. Even then, be skeptical. Treat every PC you may encounter as if it’s infected. Don’t stick a USB drive into a public computer, for example, unless you’re prepared to disinfect the USB drive immediately when you get back to a safe computer. Assume that everything you type into a public PC is being logged and sent to a pimply-face genius who wants to be a millionaire.

Don’t trust any PC unless you, personally, have been taking close care of it. Even then, be skeptical. Treat every PC you may encounter as if it’s infected. Don’t stick a USB drive into a public computer, for example, unless you’re prepared to disinfect the USB drive immediately when you get back to a safe computer. Assume that everything you type into a public PC is being logged and sent to a pimply-face genius who wants to be a millionaire.

![]() Don’t install a new program unless you know precisely what it does, and you’ve checked to make sure you have a legitimate copy.

Don’t install a new program unless you know precisely what it does, and you’ve checked to make sure you have a legitimate copy.

Yes, even if an online scanner told you that you have 139 viruses on your computer, and you need to pay just $49.99 to get rid of them.

Yes, even if an online scanner told you that you have 139 viruses on your computer, and you need to pay just $49.99 to get rid of them.

If you install apps from the Windows Store, you're safe. But any programs you install on your desktop should be vetted ten ways from Tuesday, downloaded from a reputable source (such as www.cnet.com, www.sourceforge.net, www.softpedia.com, www.majorgeeks.com, www.tucows.com, www.snapfiles.com), and even then you need to ask yourself whether you really need the program, and even then you have to be careful that the installer doesn't bring in some crappy extras like browser toolbars.

![]() Don’t use the same password for two or more sites. Okay, if you reuse your passwords, make sure you don’t reuse the passwords on any of your e-mail or financial accounts.

Don’t use the same password for two or more sites. Okay, if you reuse your passwords, make sure you don’t reuse the passwords on any of your e-mail or financial accounts.

True confession time. Yes, I reuse passwords. Everybody does. LastPass (see Book IX, Chapter 4) makes it easier to create a different password for every website, but I’m lazy sometimes.

True confession time. Yes, I reuse passwords. Everybody does. LastPass (see Book IX, Chapter 4) makes it easier to create a different password for every website, but I’m lazy sometimes.

E-mail accounts are different. If you reuse the passwords on any of your e-mail accounts and somebody gets the password, he may be able to break into everything, steal your money, and besmirch your reputation. See the nearby “Don’t reuse your e-mail password” sidebar.

![]() Don’t use Wi-Fi in a public place unless you’re running exclusively on HTTPS-encrypted sites or through a virtual private network (VPN).

Don’t use Wi-Fi in a public place unless you’re running exclusively on HTTPS-encrypted sites or through a virtual private network (VPN).

If you don’t know what HTTPS is and have never set up a VPN, that’s okay. Just realize that anybody else who can connect to the same Wi-Fi station you’re using can see every single thing that goes into or comes out of your computer. See Book VIII, Chapter 4.

If you don’t know what HTTPS is and have never set up a VPN, that’s okay. Just realize that anybody else who can connect to the same Wi-Fi station you’re using can see every single thing that goes into or comes out of your computer. See Book VIII, Chapter 4.

![]() Don’t fall for Nigerian 419 scams, “I’ve been mugged and I need $500 scams,” or anything else where you have to send money. There are lots of scams — and if you hear the words “Western Union” or “Postal Money Order,” run for the exit. See Book IX, Chapter 1.

Don’t fall for Nigerian 419 scams, “I’ve been mugged and I need $500 scams,” or anything else where you have to send money. There are lots of scams — and if you hear the words “Western Union” or “Postal Money Order,” run for the exit. See Book IX, Chapter 1.

![]() Don’t tap or click a link in an e-mail message or document and expect it to take you to a financial site. Take the time to type the address into your browser. You’ve heard it a thousand times, but it’s true.

Don’t tap or click a link in an e-mail message or document and expect it to take you to a financial site. Take the time to type the address into your browser. You’ve heard it a thousand times, but it’s true.

![]() Don’t open an attachment to any e-mail message until you’ve contacted the person who sent it to you and verified that she intentionally sent you the file. Even if she did send it, you need to use your judgment as to whether the sender is savvy enough to refrain from sending you something infectious.

Don’t open an attachment to any e-mail message until you’ve contacted the person who sent it to you and verified that she intentionally sent you the file. Even if she did send it, you need to use your judgment as to whether the sender is savvy enough to refrain from sending you something infectious.

No, UPS didn’t send you a non-delivery notice in a Zip file, Microsoft didn’t send you an update to Windows attached to a message, and your winning lottery notification won’t come as an attachment.

![]() Don’t forget to change your passwords. Yeah, another one of those things everybody recommends, but nobody does. Except you really should.

Don’t forget to change your passwords. Yeah, another one of those things everybody recommends, but nobody does. Except you really should.

![]() Don’t trust anybody who calls you and offers to fix your computer. The “I’m from Microsoft and I’m here to help” scam has gone too far. Stay skeptical, and don’t let anybody else into your computer, unless you know who he is. See Book IX, Chapter 1.

Don’t trust anybody who calls you and offers to fix your computer. The “I’m from Microsoft and I’m here to help” scam has gone too far. Stay skeptical, and don’t let anybody else into your computer, unless you know who he is. See Book IX, Chapter 1.

![]() Don’t forget that the biggest security gap is between your ears. Use your head, not your tapping or clicking finger.

Don’t forget that the biggest security gap is between your ears. Use your head, not your tapping or clicking finger.

Making Sense of Malware

Although most people are more familiar with the term virus, viruses are only part of the problem — a problem known as malware. Malware is made up of the elements described in this list:

![]() Viruses: A computer virus is a program that replicates. That’s all. Viruses generally replicate by attaching themselves to files — programs, documents, or spreadsheets — or replacing “genuine” operating system files with bogus ones. They usually make copies of themselves whenever they’re run.

Viruses: A computer virus is a program that replicates. That’s all. Viruses generally replicate by attaching themselves to files — programs, documents, or spreadsheets — or replacing “genuine” operating system files with bogus ones. They usually make copies of themselves whenever they’re run.

You probably think that viruses delete files or make programs go belly-up or wreak havoc in other nefarious ways. Some of them do. Many of them don’t. Viruses sound scary, but most of them aren’t. Most viruses have such ridiculous bugs in them that they don’t get far “in the wild.”

You probably think that viruses delete files or make programs go belly-up or wreak havoc in other nefarious ways. Some of them do. Many of them don’t. Viruses sound scary, but most of them aren’t. Most viruses have such ridiculous bugs in them that they don’t get far “in the wild.”

![]() Trojans: Trojans (occasionally called Trojan horses) may or may not be able to reproduce, but they always require that the user do something to get them started. The most common Trojans these days appear as programs downloaded from the Internet, or e-mail attachments, or programs that helpfully offer to install themselves from the Internet: You tap or double-click an attachment, expecting to open a picture or a document, and you get bit when a program comes in and clobbers your computer, frequently sending out a gazillion messages, all with infected attachments, without your knowledge or consent.

Trojans: Trojans (occasionally called Trojan horses) may or may not be able to reproduce, but they always require that the user do something to get them started. The most common Trojans these days appear as programs downloaded from the Internet, or e-mail attachments, or programs that helpfully offer to install themselves from the Internet: You tap or double-click an attachment, expecting to open a picture or a document, and you get bit when a program comes in and clobbers your computer, frequently sending out a gazillion messages, all with infected attachments, without your knowledge or consent.

![]() Worms: Worms move from one computer to another over a network. The worst ones replicate very quickly by shooting copies of themselves over the Internet, taking advantage of holes in the operating systems (all too frequently, Windows).

Worms: Worms move from one computer to another over a network. The worst ones replicate very quickly by shooting copies of themselves over the Internet, taking advantage of holes in the operating systems (all too frequently, Windows).

Viruses, Trojans, and worms are getting much, much more sophisticated than they were just a few years ago. There’s a lot of money to be made with advanced malware.

Some malware can carry bad payloads (programs that wreak destruction on your system), but many of the worst offenders cause the most harm by clogging networks (nearly bringing down the Internet itself, at times) and by turning PCs into zombies, frequently called bots, which can be operated by remote control. (I talk about bots and botnets in Book IX, Chapter 1.)

All these definitions are becoming more academic and less relevant, as the trend shifts to blended-threat malware. Blended threats incorporate elements of all three traditional kinds of malware — and more. Most of the most successful “viruses” you read about in the press these days — Rustock, Aleuron, and the like — are, in fact, blended-threat malware. They’ve come a long way from old-fashioned viruses.

Scanning for Rootkits with Windows Defender Offline

Windows Defender Offline (WDO) sniffs out and removes rootkits. WDO should occupy a key spot in your bag of tricks. It works like a champ on Windows XP, Vista, Windows 7, 8, and Windows 8.1 systems and should be able to catch a wide variety of nasties that evade detection by more traditional methods.

Windows Defender Offline can help in two very different situations:

![]() When Windows won’t boot, you can boot your machine with a WDO CD or USB drive and have WDO perform a malware scan.

When Windows won’t boot, you can boot your machine with a WDO CD or USB drive and have WDO perform a malware scan.

![]() If you think you may have a rootkit — or even if you’re just curious — WDO can scan your system and remove many different kinds of rootkits.

If you think you may have a rootkit — or even if you’re just curious — WDO can scan your system and remove many different kinds of rootkits.

It’s important to understand that, even though Microsoft makes and distributes WDO, it is not a Windows application; it doesn’t use the copy of Windows installed on your PC. Rather, it’s completely self-contained — you boot with the WDO CD or USB drive, and WDO looks at your system without any interference from the installed copy of Windows.

To get WDO up and running, make sure you have a blank CD, DVD, or USB flash drive with at least 250MB of free space. Then follow these steps:

1. Figure out the “bittedness” of the computer that’s going to get scanned.

If you don’t already know whether your PC is running 32-bit or 64-bit Windows, right-click the lower-left corner of the screen and choose System. (If you don’t have a mouse, flip to the desktop, swipe from the right, choose the Settings charm, and at the top, tap Control Panel. Tap the System and Security link, and then tap the System link. And consider buying a mouse.) Windows responds with the System window, as shown in Figure 2-2, and near the middle, it tells you whether you have a 32-bit or 64-bit system.

Figure 2-2: The System window tells you the bittedness of your PC.

You can use any Windows computer for the following steps — you don’t have to use the PC that’s going to get scanned.

If you’re going to create a CD or DVD to boot WDO, you do have to use a PC with a CD or DVD writer. To create a bootable USB drive, the downloading computer has to have a USB port.

2. Go to the Windows Defender Offline site, click and download either the 32-bit or 64-bit version, depending on the bittedness of the system you’re going to scan. Tap or double-click to run the downloaded file.

The WDO site can be found at www.windows.microsoft.com/en-US/windows/what-is-windows-defender-offline.

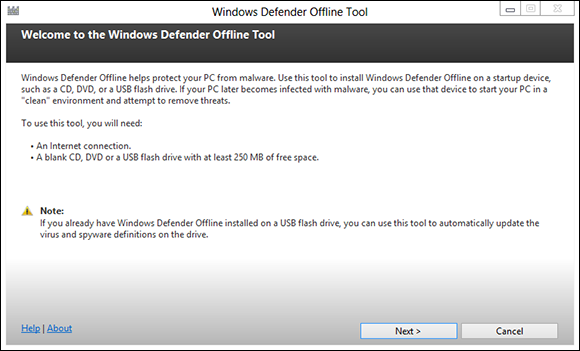

The welcome pane appears, as shown in Figure 2-3.

3. Tap or click Next, accept all the defaults, choose whether you want to use a CD, DVD, or USB drive, and then tap or click Finish.

The ISO file option is primarily for people who are going to run WDO on systems that can boot from an ISO file, which usually means a virtual machine.

If you’re going to create a bootable USB drive, be aware that this installer wipes out everything on the drive.

If you’re going to create a bootable USB drive, be aware that this installer wipes out everything on the drive.

The installer downloads the latest version of the software and signature files (about 210MB for the 32-bit version or 230MB for the 64-bit version) and then creates the boot drive, or the ISO file.

Figure 2-3: You need to sacrifice a CD, DVD, or USB drive to hold the WDO booter.

4. With a bootable CD, DVD, or USB drive properly inserted, boot the PC you want to examine from the device.

If you've never booted the machine from CD or USB before and can't figure out how to jimmy the BIOS to make it work, Microsoft has some suggestions for getting it to work at www.windows.microsoft.com/en-US/windows/windows-defender-offline-faq.

5. If you have a multiboot system, choose which OS you wish to scan.

WDO will scan only one system at a time.

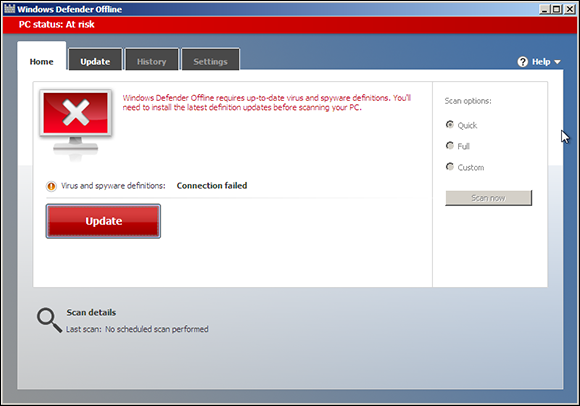

With the OS chosen, you see a Windows 7–like startup screen that dissolves into the Windows Defender Offline screen, as shown in Figure 2-4.

Figure 2-4: Windows Defender Offline may need to be updated before it will scan your system.

6. Update the definitions if need be, by tapping or clicking the Update button. Choose a Quick, Full, or Custom scan, and then tap or click the Scan Now button.

The Full scan option is very thorough — it looks inside all the files on the system, including ancient backed-up e-mails — and can run for six or eight hours. The Custom option lets you select drives and folders for scanning. In my tests on a fresh Windows 8.1 machine, the Full scan took only 30 minutes.

If WDO finds potential threat(s), it displays warning(s) identical to the warning dialog box in Windows Defender.

7. Choose to Remove, Quarantine, or Ignore the threat.

See Book IX, Chapter 3 for a discussion of the options and what they mean. Hint: Unless you have an overwhelming need to do otherwise, choose Remove.

See Book IX, Chapter 3 for a discussion of the options and what they mean. Hint: Unless you have an overwhelming need to do otherwise, choose Remove.

Deciphering Browsers’ Inscrutable Warnings

One last trick that may help you head off an unfortunate online incident: Each browser has subtle ways of telling you that you may be in trouble. I’m not talking about the giant Warning: Suspected Phishing Site or Reported Web Forgery signs. Those are supposed to hit you upside the head, and they do.

I’m talking about the gentle indications each browser has that tell you whether there’s something strange about the site you’re looking at. Historic-ally, if you’re on a secured page — where encryption is in force between you and the website — you see a padlock. That simple padlock indicator has grown up a bit, so you can understand more about your secure (or not-so-secure) connection with a glance.

Chrome

Chrome browsers have four different icons that can appear to the left of a site’s URL, as shown in Figure 2-5.

Figure 2-5: The four different HTTPS padlocks in Chrome.

Here’s what they mean:

![]() The world icon doesn’t look like a padlock because it indicates that the site isn’t secure. As long as you don’t have to type anything into a site, there’s no great reason to require a secure site. If you’re asked to provide information on an unsecure site, be intensely aware that it can be seen by anybody who’s snooping on your connection.

The world icon doesn’t look like a padlock because it indicates that the site isn’t secure. As long as you don’t have to type anything into a site, there’s no great reason to require a secure site. If you’re asked to provide information on an unsecure site, be intensely aware that it can be seen by anybody who’s snooping on your connection.

![]() The green padlock says that there’s a secure connection in place, and it’s working. As long as you’re looking at the correct domain — you didn’t mistype the domain name, for example — you’re safe.

The green padlock says that there’s a secure connection in place, and it’s working. As long as you’re looking at the correct domain — you didn’t mistype the domain name, for example — you’re safe.

If the site has an Extended Validation certificate (see the nearby “What is Extended Validation?” sidebar), you will also see green highlighting in the address bar.

![]() The yellow warning on a padlock says that Chrome has set up a secure connection, but there are parts of the page that can, conceivably, snoop on what you’re typing. That’s what the “insecure content” warning means.

The yellow warning on a padlock says that Chrome has set up a secure connection, but there are parts of the page that can, conceivably, snoop on what you’re typing. That’s what the “insecure content” warning means.

![]() The red X on a padlock tells you that there are problems with the site’s certificate, or that “insecure content” on the page is known to be high risk. When you hit a red X, you have to ask yourself whether the site’s handlers just let the certificate lapse (I’ve seen that on banking sites and other sites that shouldn’t go bad) or if there’s something genuinely wrong with the site.

The red X on a padlock tells you that there are problems with the site’s certificate, or that “insecure content” on the page is known to be high risk. When you hit a red X, you have to ask yourself whether the site’s handlers just let the certificate lapse (I’ve seen that on banking sites and other sites that shouldn’t go bad) or if there’s something genuinely wrong with the site.

Firefox

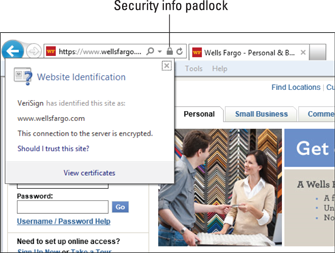

Firefox handles things a little differently. Firefox puts a box to the left of the URL — called a Site Identity Button (see Figure 2-6) — that’s color-coded to give you an idea of what’s in store. If you tap or click the button, you see detailed information about the security status of the site.

Figure 2-6: Firefox gives detailed, site security information, like the fact that Wells Fargo doesn’t identify its site.

The three colors indicate

![]() Gray: Not a secure site

Gray: Not a secure site

![]() Blue: Basic security information

Blue: Basic security information

![]() Green: Complete security information, including an Extended Validation certificate (see the “What is Extended Validation?” sidebar)

Green: Complete security information, including an Extended Validation certificate (see the “What is Extended Validation?” sidebar)

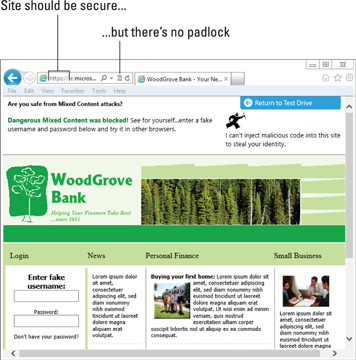

Internet Explorer 11

Internet Explorer 11 has yet another way to tell you about potential problems. It has a padlock icon that works much like the analogous icons in Chrome and Firefox, as shown in Figure 2-7.

Figure 2-7: IE shows site security information if you tap or click the padlock icon.

The padlock icons in the desktop version of Internet Explorer look like this:

![]() No padlock means the connection isn’t secure.

No padlock means the connection isn’t secure.

![]() A gray padlock is for standard security.

A gray padlock is for standard security.

![]() A gray padlock plus green highlights in the address bar is for Extended Validation sites (see the “What is Extended Validation?” sidebar).

A gray padlock plus green highlights in the address bar is for Extended Validation sites (see the “What is Extended Validation?” sidebar).

In addition, IE has a huge variety of nuanced messages, such as the one in Figure 2-8. This Microsoft-constructed demo page shows how an HTTPS site may not trigger a padlock icon in Internet Explorer 11. (Note: There’s no padlock indication next to the web address.)

More than a dozen messages can appear at the top or bottom of the screen. For details, see blogs.msdn.com/b/ie/archive/2011/06/23/internet-explorer-9-security-part-4-protecting-consumers-from-malicious-mixed-content.aspx.

Figure 2-8: A supposedly secure HTTPS site contains parts that aren’t secure.