Chapter 1: Spies, Spams, Scams — They’re Out to Get You

In This Chapter

![]() Determining which hazards and hoaxes to look out for

Determining which hazards and hoaxes to look out for

![]() Keeping up to date with reliable sources

Keeping up to date with reliable sources

![]() Figuring out whether you’re infected

Figuring out whether you’re infected

![]() Protecting yourself

Protecting yourself

Windows XP had more holes than a prairie-dog field. Vista was built on top of Windows XP, and the holes were hidden better. Windows 7 included truly innovative security capabilities; it represented the first really significant break from XP’s lethargic approach to security.

Windows 8 included marginal security improvements to Windows itself, but better safety nets to keep you from shooting yourself in the foot. Also a fully functional, very capable antivirus program is built in. That’s important.

Windows 8.1’s security improvements over Win8 are marginal, but at least we haven’t gone backwards.

Targeted infections, though, are another story. There’s a lot of money to be made — and important governments to please — with very narrowly defined information-gathering techniques. Unless you work for a defense contractor or a Tibetan relief organization, you probably don’t have much to worry about. But it doesn’t hurt to keep your guard up.

In this chapter, I explain the source of real threats. (More details follow in the upcoming chapters in this minibook.) I bet it’ll surprise you to find out that Adobe and Oracle let more bad guys into Windows boxes than Microsoft. I also take you outside the box, to show you the kinds of problems people face with their computer systems and to look at a few key solutions.

Most of all, I want you to understand that (1) you shouldn’t take a loaded gun, point it at your foot, aim carefully, and pull the trigger, and (2) if you’re smart and can control your clicking finger, you don’t need to spend a penny on malware protection.

Understanding the Hazards — and the Hoaxes

Many of the best-known Internet-borne scares in the past decade — the Rustocks, Waledacs, Esthosts, Confickers, Mebroots, Bagles, Netskys, Melissas, ILOVEYOUs, Blasters and Slammers, and their ilk — work by using the programmability built in to the computer application itself or by taking advantage of Windows holes to inject themselves into unprotected machines (see Figure 1-1).

Fast-forward a dozen years, and the concepts have changed. The old threats are still there, but they’ve taken on a new twist: The scent of money, and sometimes political motivation, has made cracking (or breaking in to PCs for nefarious ends) far more sophisticated. What started as a bunch of miscreants playing programmer one-upmanship at your expense has turned into a profitable — sometimes highly profitable — business enterprise.

Figure 1-1: The Conficker worm employs programm-ability built in to Windows or security holes that had been patched months earlier.

The primary infection vectors

How do people really get infected?

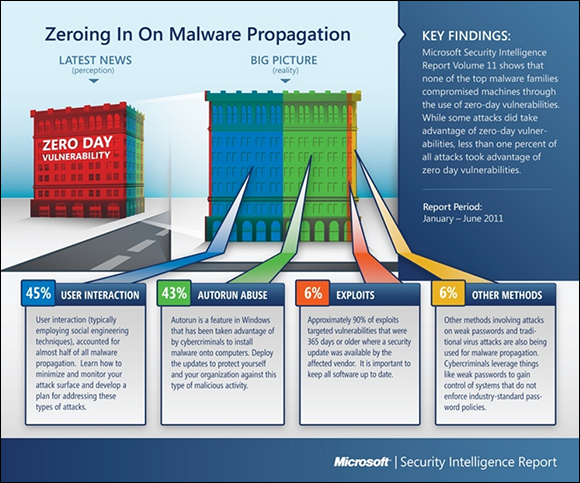

According to Microsoft’s Security Intelligence Report 11, the single greatest security gap is the one between your ears. See Figure 1-2.

Many years ago, the biggest PC threat came from newly discovered security holes: The bad guys use the holes before you get your machine patched, and you’re toast. They traded ’em like baseball cards. Those holes still get a lot of attention, especially in the press, but they aren’t the leading cause of widespread infection. Not even close. A very large majority of infections happen when people get tricked into clicking something they shouldn’t.

Figure 1-2: Most infections happen when people don’t think about what they’re doing.

Narrow, targeted infections, though, tend to rely on previously unknown security holes. It’s hard for the big boys to protect against that kind of attack. Little folks like you and me don’t really stand a chance.

Zombies and botnets

Every month, Microsoft posts a new Malicious Software Removal Tool that scans PCs for malware and, in many cases, removes it. In a recent study, Microsoft reported that 62 percent of all PC systems that were found to have malicious software also had backdoors. That’s a sobering figure.

A backdoor program breaks through the usual Windows security measures and allows a cretin to take control of your computer over the Internet, effectively turning your machine into a zombie. The most sophisticated backdoors allow creeps to adapt (upgrade, if you will) the malicious software running on a subverted machine. And they do it by remote control.

Backdoors frequently arrive on your PC when you install a program you want, not realizing that the backdoor came along for the ride.

Less commonly, PCs acquire backdoors when they come down with some sort of infection: The ZeuS, Rustock, Waledac, TDL4/Alureon, Conficker, Mebroot, Mydoom, and Sobig worms installed backdoors. Many of the infections occur on PCs that haven’t kept Java, Flash, or the Adobe Acrobat Reader up to date. The most common mechanism for infection is a buffer overflow (see the nearby “What’s a buffer overflow?” sidebar).

A cretin who controls one machine by way of a backdoor can’t claim much street “cred.” But someone who puts together a botnet — a collection of hundreds or thousands of PCs — can take his zombies to the bank:

![]() A botnet running a keylogger (a program that watches what you type and sporadically sends the data to the botnet’s controller) can gather all sorts of valuable information. The single biggest problem facing those who gather and disseminate keylogger information? Bulk — the sheer volume of stolen information. How do you scan millions of characters of logged data and retrieve a bank account number or a password?

A botnet running a keylogger (a program that watches what you type and sporadically sends the data to the botnet’s controller) can gather all sorts of valuable information. The single biggest problem facing those who gather and disseminate keylogger information? Bulk — the sheer volume of stolen information. How do you scan millions of characters of logged data and retrieve a bank account number or a password?

![]() Unscrupulous businesses hire botnet controllers to disseminate spam, “harvest” e-mail addresses, and even direct coordinated distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks against rivals’ websites. (A DDoS attack guides thousands of PCs to go to a particular website simultaneously, blocking legitimate use.)

Unscrupulous businesses hire botnet controllers to disseminate spam, “harvest” e-mail addresses, and even direct coordinated distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks against rivals’ websites. (A DDoS attack guides thousands of PCs to go to a particular website simultaneously, blocking legitimate use.)

There’s a fortune to be made in botnets. The Rustock botnet alone was responsible for somewhere between 10 and 30 billion pieces of spam per day. Spammers paid the Rustock handlers, either directly or on commission, based on the number of referrals.

The most successful botnets run as rootkits, programs (or collections of programs) that operate deep inside Windows, concealing files and making it extremely difficult to detect their presence.

That said, Microsoft has been roundly criticized by members of the security community for "hampering and even compromising a number of large international investigations in the United States, Europe, and Asia" while trying to dispense swift justice (www.krebsonsecurity.com/2012/04/microsoft-responds-to-critics-over-botnet-bruhaha).

Botnets on Windows 8 and Windows 8.1 aren’t common, but somebody, some day, is going to figure out how to shoehorn them in.

Phishing

Did you get a message from someone on eBay saying that you had better pay for the computer you bought or else he’ll report you? Gotcha. Perhaps a notification that you have received an online greeting card from a family member — and when you try to retrieve it, you have to join the greeting card site and enter a credit card number? Gotcha again.

Phishing — sending e-mail that attempts to extract personal information from you, usually by using a bogus website — has in many cases reached levels of sophistication that exceed the standards of the financial institutions themselves. Some phishing messages, such as the bogus message in Figure 1-3, warn you about the evils of phishing, in an attempt to persuade you to send your account number and password to a scammer in Kazbukistan (or New York).

Figure 1-3: If you click the link, you open a page that looks much like the PayPal page, and any information you enter is sent to a scammer.

Here’s how phishing works:

1. A scammer, often using a fake name and a stolen credit card, sets up a website.

Usually it’s quite a professional-looking site — in some cases, indistinguishable from the authentic site.

2. The website asks for personal information — most commonly, your account number and password or the PIN for your ATM card. See Figure 1-4 for an example.

Figure 1-4: This is a fake eBay sign-on site. Can you tell the difference from the original?

3. The scammer turns spammer and sends hundreds of thousands of bogus messages.

The messages include a clickable link to the fake website and a plausible story about how you must go to the website, log on, and do something to avoid dire consequences. The From address on the messages is spoofed so that the message appears to come from the company in question.

The message usually includes official logos — many even include links to the real website, even though they encourage you to click through to the fake site.

4. A small percentage of the recipients of the spam e-mail open it and click through to the fake site.

5. If they enter their information, it’s sent directly to the scammer.

6. The scammer watches incoming traffic from the fake website, gathers the information typed by gullible people, and uses it quickly — typically, by logging on to the bank’s website and attempting a transfer or by burning a fake ATM card and using the PIN.

7. Within a day or two — or sometimes just hours — the website is shut down, and everything disappears into thin ether.

Phishing has become hugely popular because of the sheer numbers involved. Say a scammer sends 1 million e-mail messages advising Wells Fargo customers to log on to their accounts. Only a small fraction of all the people who receive the phishing message will be Wells Fargo customers, but if the hit rate is just 1 percent, that’s 10,000 customers.

Most of the Wells Fargo customers who receive the message are smart enough to ignore it. But a sizable percentage — maybe 10 percent, maybe just 1 percent — will click through. That’s somewhere between 100 and 1,000 suckers, er, customers.

If half the people who click through provide their account details, the scammer gets 50 to 500 account numbers and passwords. If most of those arrive within a day of sending the phishing message, the scammer stands to make a pretty penny indeed — and she can disappear with hardly a trace.

Here’s how to fight against phishing:

![]() Use the latest versions of Internet Explorer, Firefox, or Chrome. All three contain sophisticated — although not perfect — antiphishing features that warn you before you venture to a phishy site. See the warning in Figure 1-5.

Use the latest versions of Internet Explorer, Firefox, or Chrome. All three contain sophisticated — although not perfect — antiphishing features that warn you before you venture to a phishy site. See the warning in Figure 1-5.

Figure 1-5: If enough people report a site as being dangerous, you see a warning like this one from Firefox.

![]() If you encounter a website that looks like it may be a phishing site, report it. Use the tools in IE, Firefox, or Chrome. Use all three, if you have a chance! Here’s how:

If you encounter a website that looks like it may be a phishing site, report it. Use the tools in IE, Firefox, or Chrome. Use all three, if you have a chance! Here’s how:

• In the desktop version of Internet Explorer, tap or click the Tools icon (the one that looks like a gear) and choose Safety, Report Unsafe Website. In the tiled full-screen version of IE, swipe from the top or bottom, or right-click, choose the Page Tools icon (which looks like a wrench), and choose View on the Desktop. That takes you to the desktop version of IE, where you can report the page.

• Chrome and Firefox use the same malicious site database. To report a site, go to www.google.com/safebrowsing/report_phish/.

![]() If you receive an e-mail message that contains any links to the web, don’t click them. Nowadays, almost all messages with links to commercial sites are phishing come-ons. Financial institutions, in particular, don’t send messages with links any more — and few other companies would dare. If you feel motivated to check out a dire message — for example, if it looks like somebody on eBay is planning to sue you for something you didn’t do — open your favorite browser and type the address of the company by hand.

If you receive an e-mail message that contains any links to the web, don’t click them. Nowadays, almost all messages with links to commercial sites are phishing come-ons. Financial institutions, in particular, don’t send messages with links any more — and few other companies would dare. If you feel motivated to check out a dire message — for example, if it looks like somebody on eBay is planning to sue you for something you didn’t do — open your favorite browser and type the address of the company by hand.

You can see which site a link really points to by hovering your mouse over the link. There’s no tap equivalent just yet.

![]() Never include personal information in an e-mail message and send it. Don’t give out any of your personal information unless you manually log on to the company’s website. Remember that unless you encrypt your e-mail messages, they travel over the Internet in plain-text form. Anybody who’s “sniffing” the mail can see everything you’ve written. It’s roughly analogous to sending a postcard, with the NSA as the addressee, and Google and Microsoft on the cc list.

Never include personal information in an e-mail message and send it. Don’t give out any of your personal information unless you manually log on to the company’s website. Remember that unless you encrypt your e-mail messages, they travel over the Internet in plain-text form. Anybody who’s “sniffing” the mail can see everything you’ve written. It’s roughly analogous to sending a postcard, with the NSA as the addressee, and Google and Microsoft on the cc list.

![]() If you receive a phishing message that may be new or different, check

If you receive a phishing message that may be new or different, check www.millersmiles.co.uk to see whether it's a well-known, uh, phish. If you don't see your phish listed, submit a copy using the instructions at www.millersmiles.co.uk/submit.php. Hold on to the message for a while to see whether the authorities need a copy of the message header: If so, it'll send you instructions.

Figure 1-6: MillerSmiles maintains a huge database of phishing messages and offers sage advice about identifying, reporting, and recovering from phishing attacks.

419 scams

Greetings,

I am writing this letter to you in good faith and I hope my contact with you will transpire into a mutual relationship now and forever. I am Mrs. Omigod Mugambi, wife of the late General Rufus Mugambi, former Director of Mines for the Dufus Diamond Dust Co Ltd of Central Eastern Lower Leone . . .

I’m sure you’re smart enough to pass over e-mail like that. At least, I hope so. It’s an obvious setup for the classic 419 (“four one nine”) scam — a scam so common that it has a widely accepted name, which derives from Nigerian Criminal Code Chapter 38, Article 419.

Much more sophisticated versions of the 419 scam are making the rounds today. The basic approach is to convince you to send money to someone, usually via Western Union. If you send the money, you’ll never see it again, no matter how hard the sell or dire the threatened consequences.

Here’s one of the new variations of the old 419. It all starts when you place an ad that appears online. It doesn’t really matter what you’re selling, as long as it’s physically large and valuable. It doesn’t matter where you advertise — I’ve seen reports of this scam being played on Craigslist advertisers and major online sites, tiny nickel ad publishers, local newspapers, and anywhere else ads are placed.

“Let me know the price in USD? I am OK with the item it looks like new in the photos I am from Liverpool U.K., i am sorry i will not be able to come for the viewing, i will arrange for the pickup after payment has been made, all documentation will be done by the shipper, so you don’t have to worry about that. Thanks”

Three key points:

![]() The scammer is using a Gmail address, which can’t be traced with anything short of a court order.

The scammer is using a Gmail address, which can’t be traced with anything short of a court order.

![]() He claims to be out of the country, which makes pursuing him very difficult.

He claims to be out of the country, which makes pursuing him very difficult.

![]() He claims that he has a shipper who will pick up the item. The plot thickens.

He claims that he has a shipper who will pick up the item. The plot thickens.

Also, his grammar falls somewhere between atrocious and unintelligible. Unfortunately, that isn’t a sure sign, but it’s not bound to inspire confidence.

I wrote back and gave him a price, but I expressed concern about the shipper. He wrote that he would send the shipper from the U.K. for pickup and said, “I will be paying the PayPal charges from my account and i will be paying directly into your PayPal account without any delay, and i hope you have a PayPal account.”

I gave him a dormant PayPal account, listing my address as that of the local police station. He wrote back quite quickly:

“I have just completed the Payment and i am sure you have received the confirmation from PayPal regarding the Payment. You can check your paypal e-mail for confirmation of payment.a total of 25,982usd was sent, 24,728usd for the item and the extra 1,200usd for my shipper’s charges, which you will be sending to the address below via western union” and then he gave me the name of someone in Devon, U.K. “You should send the money soon so that the Pick Up would be scheduled and you would know when the Pick Up would commence, make sure you’re home. I advice you to check both your inbox or junk/spam folder for the payment confirmation message.”

I then received a message that claimed to be from Service-Intl.PayPal.Com:

“The Transaction will appear as soon as the western union information is received from you,we have to follow this procedure due to some security reason... the Money was sent through the Service Option Secure Payment so that the transaction can be protected with adequate security measures for you to be able to receive your money. The Shipping Company only accept payment through Western Union You have nothing to doubt about, You are safe and secured doing this transaction and your account will be credited immediately the western union receipt of *1,200USD* is received from you.”

Figure 1-7: Oh me, oh my, he’s going to send the FBI.

In the end, the scammer and his cohorts were quite sloppy. Most of the time when scammers send e-mail from “PayPal,” they use a virtual private network (VPN; see Book VIII, Chapter 4) to make it look like the mail came from the United States. But on three separate occasions, the scammer I was conversing with forgot to turn on the VPN. Using a very simple technique, I traced all three messages back to one specific Internet service provider in Lagos, Nigeria.

So I had three scamming messages with identified IP addresses, the name of a large Internet service provider in Nigeria, and a compelling case for PayPal (to defend its name) and Western Union (which was being used as a drop) to follow up.

“All our 3G network subscribers now sit behind a small number of IP addresses. This is done via a technology called network address translation (NAT). In essence, it means that 1 million subscribers may appear to the outside world as one subscriber because they are all using the same IP address.”

So now you know why Nigerians love to conduct their scams over the Nigerian 3G network. No doubt MTN Nigeria could sift through its NAT logs and find out who was connected at precisely the right time, but tracing a specific e-mail back to an individual would be difficult, if not impossible — and it would certainly require a court order.

If you know anybody who posts ads online, you may want to warn him.

I’m from Microsoft and I’m here to help

This kind of scam really hurts me, personally, because I’ve made a career out of helping people with Microsoft problems.

You explain the problem to her. Then one of two things happens. Either she requests your 25-character Windows activation key or she asks for permission to connect to your computer, typically using Remote Assistance (see Book VII, Chapter 2).

If you give her your activation key — or she looks up your validation key while she’s controlling your PC — she’ll pretend to refer to the “Microsoft registration database” (or something similar) and give you the bad news that your machine is all screwed up, and it’s out of warranty, but she can fix it for a mere $189.

The overwhelming con give-away — the big red flag — in all this: Microsoft doesn’t work that way. Think about it. Microsoft isn’t going to call you to solve your problems, unless you’ve received a very specific commitment from a very specific individual in the organization — a commitment that invariably comes only after repeated phone calls on your part, generally accompanied by elevation to lofty levels of the support organization on multiple continents, frequently in conjunction with high-decibel histrionics. Microsoft doesn’t respond to random online requests for help by calling a customer. Sorry. Doesn’t happen.

If the con is being run from overseas — much more common in these days of nearly-free VoIP cold calling — your chances of nailing the perpetrator runs from extremely slim to none. So be overly suspicious of any “Microsoft Expert” who doesn’t seem to be calling from your country.

If you’ve already been conned — given out personal information or a credit card number — start by contacting your bank or the credit card issuing company and follow its procedures for reporting identity theft.

0day exploits

What do you do when you discover a brand-new security hole in Windows or Office or another Microsoft product? Why, you sell it, of course.

When a person writes a malicious program that takes advantage of a newly discovered security hole — a hole that even the manufacturer doesn’t know about — that malicious program is a 0day exploit. (Fuddy-duddies call it “zero-day exploit.” The hopelessly hip say “sploit.”)

0days are valuable. In some cases, very valuable. HP has a subsidiary — TippingPoint — that buys 0day exploits. TippingPoint works with the software manufacturer to come up with a fix for the exploit, but at the same time, it sells corporate customers immediate protection against the exploit. “TippingPoint’s goal for the Zero Day Initiative is to provide our customers with the world’s best intrusion prevention systems and secure converged networking infrastructure.” TippingPoint offers up to $10,000 for a solid security hole.

Rumor has it that several less-than-scrupulous sites arrange for the buying and selling of new security holes. Apparently, the Russian hacker group that discovered a vulnerability in the way Windows handles WMF graphics files sold its new hole for $4,000, not realizing that it could’ve made much more. In 2012, Forbes Magazine estimated the value of 0days as ranging from $5,000 to $250,000. You can check it out at the following URL:

According to Forbes, some government agencies are in the market. Governments certainly buy 0day exploits from Vupen, a notorious 0day brokering firm. The problem (some would say “opportunity”) is getting worse, not better. Governments are now widely rumored to have thousands — some of them, tens of thousands — of stockpiled 0day exploits at hand.

Staying Informed

When you rely on the evening news to keep yourself informed about the latest threats to your computer’s well-being, you quickly discover that the mainstream press frequently doesn’t get the details right. Hey, if you were a newswriter with a deadline ten minutes away and you had to figure out how the new Bandersnatch 0day exploit shreds through a Windows TCP/IP stack buffer — and you had to explain your discoveries to a TV audience, at a presumed sixth-grade intelligence level — what would you do?

The following sections offer tips on getting the facts.

Relying on reliable sources

Fortunately, some reliable sources of information exist on the Internet. It would behoove you to check them out from time to time, particularly when you hear about a new computer security hole, real or imagined:

![]() The Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) blog presents thoroughly researched analyses of outstanding threats, from a Microsoft perspective (

The Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC) blog presents thoroughly researched analyses of outstanding threats, from a Microsoft perspective (http://blogs.technet.com/msrc).

The information you see on the MSRC blog is 100-percent Microsoft Party Line — so there’s a tendency to add more than a little “spin control” to the announcements. Nevertheless, Microsoft has the most extensive and best resources to analyze and solve Windows problems, and the MSRC blog frequently has inside information that you can’t find anywhere else.

The information you see on the MSRC blog is 100-percent Microsoft Party Line — so there’s a tendency to add more than a little “spin control” to the announcements. Nevertheless, Microsoft has the most extensive and best resources to analyze and solve Windows problems, and the MSRC blog frequently has inside information that you can’t find anywhere else.

![]() SANS Internet Storm Center (ISC) pools observations and analysis from thousands of active security researchers. You can generally get the news first — and accurately — from the ISC (

SANS Internet Storm Center (ISC) pools observations and analysis from thousands of active security researchers. You can generally get the news first — and accurately — from the ISC (http://isc.sans.org).

![]() Windows Secrets newsletter, the most-read Windows weekly ever, contains excellent recaps of all the latest problems. Also, my site, AskWoody.com (

Windows Secrets newsletter, the most-read Windows weekly ever, contains excellent recaps of all the latest problems. Also, my site, AskWoody.com (www.askwoody.com), strives to present the latest security information in a way that doesn't require a Ph.D. in computer science (www.windowssecrets.com).

Microsoft releases security patches, usually on the second Tuesday of every month. You can get advance notice about upcoming patches on the MSRC blog. When the patches become available, they’re described and presented in security bulletins bearing sequential numbers, such as MS13-001, MS13-002, and so on. The patches themselves are attached to Microsoft Knowledge Base (KB) articles with numbers resembling KB 912345. Microsoft keeps the bulletins separate from the patching programs because a single security bulletin may have many associated patches. I talk about the bulletins in Book VIII, Chapter 3.

From time to time, Microsoft also releases security advisories, which generally warn about newly discovered 0day threats in Microsoft products. You can find those, too, at the MSRC blog.

Ditching the hoaxes

Tell me whether you’ve heard any of these:

![]() “Amazing Speech by Obama!” “CNN News Alert!” “UPS Delivery Failure,” “Hundreds killed in [insert a disaster of your choice],” “Budweiser Frogs Screensaver!” “Microsoft Security Patch Attached.”

“Amazing Speech by Obama!” “CNN News Alert!” “UPS Delivery Failure,” “Hundreds killed in [insert a disaster of your choice],” “Budweiser Frogs Screensaver!” “Microsoft Security Patch Attached.”

![]() A virus will hit your computer if you read any message that includes the phrase “Good Times” in the subject line. (That one was a biggie in late 1994.) Ditto for any of the following messages: “It Takes Guts to Say ‘Jesus’,” “Win a Holiday,” “Help a poor dog win a holiday,” “Join the Crew,” “pool party,” “A Moment of Silence,” “an Internet flower for you,” “a virtual card for you,” or “Valentine’s Greetings.”

A virus will hit your computer if you read any message that includes the phrase “Good Times” in the subject line. (That one was a biggie in late 1994.) Ditto for any of the following messages: “It Takes Guts to Say ‘Jesus’,” “Win a Holiday,” “Help a poor dog win a holiday,” “Join the Crew,” “pool party,” “A Moment of Silence,” “an Internet flower for you,” “a virtual card for you,” or “Valentine’s Greetings.”

![]() A deadly virus is on the Microsoft [or insert your favorite company name here] home page. Don’t go there or else your system will die.

A deadly virus is on the Microsoft [or insert your favorite company name here] home page. Don’t go there or else your system will die.

![]() If you have a file named [insert filename here] on your PC, it contains a virus. Delete it immediately!

If you have a file named [insert filename here] on your PC, it contains a virus. Delete it immediately!

They’re all hoaxes — not a breath of truth in any of them.

Other hoaxes are just rumors that circulate among well-intentioned people who haven’t a clue. Those hoaxes hurt, too. Sometimes, when real worms hit, so much e-mail traffic is generated from warning people to avoid the worm that the well-intentioned watchdogs do more damage than the worm itself! Strange but true.

![]() A horrible virus is on the loose that’s going to bring down the Internet. (Sheesh. I get enough of that garbage on the nightly news.)

A horrible virus is on the loose that’s going to bring down the Internet. (Sheesh. I get enough of that garbage on the nightly news.)

![]() Send a copy of this message to ten of your best friends, and for every copy that’s forwarded, Bill Gates will give [pick your favorite charity] $10.

Send a copy of this message to ten of your best friends, and for every copy that’s forwarded, Bill Gates will give [pick your favorite charity] $10.

![]() Forward a copy of this message to ten of your friends and put your name at the bottom of the list. In [pick a random amount of time], you will receive $10,000 in the mail, or your luck will change for the better. Your eyelids will fall off if you don’t forward this message.

Forward a copy of this message to ten of your friends and put your name at the bottom of the list. In [pick a random amount of time], you will receive $10,000 in the mail, or your luck will change for the better. Your eyelids will fall off if you don’t forward this message.

![]() Microsoft (Intel, McAfee, Norton, Compaq — whatever) says that you need to double-click the attached file, download something, don’t download something, go to a specific place, avoid a specific place, and on and on.

Microsoft (Intel, McAfee, Norton, Compaq — whatever) says that you need to double-click the attached file, download something, don’t download something, go to a specific place, avoid a specific place, and on and on.

If you think you’ve stumbled on the world’s most important virus alert, by way of your uncle’s sister-in-law’s roommate’s hairdresser’s soon-to-be-ex-boyfriend (remember that he’s the one who’s a really smart computer guy, but kind of smelly?), count to ten twice and keep these four important points in mind:

![]() No reputable software company (including Microsoft) distributes patches by e-mail. You should never, ever, open or run an attachment to an e-mail message until you contact the person who sent it to you and confirm that she intended to send it to you.

No reputable software company (including Microsoft) distributes patches by e-mail. You should never, ever, open or run an attachment to an e-mail message until you contact the person who sent it to you and confirm that she intended to send it to you.

![]() Chances are very good (I'd say, oh, 99.9999 percent or more) that you're looking at a half-baked hoax that's documented on the web, most likely on the Snopes urban myths site (

Chances are very good (I'd say, oh, 99.9999 percent or more) that you're looking at a half-baked hoax that's documented on the web, most likely on the Snopes urban myths site (www.snopes.com).

![]() If the virus or worm is real, Brian Krebs has already written about it. Go to

If the virus or worm is real, Brian Krebs has already written about it. Go to www.krebsonsecurity.com.

![]() If the Internet world is about to collapse, clogged with gazillions of e-mail worms, the worst possible way to notify friends and family is by e-mail. D’oh! Pick up the phone, walk over to the water cooler or send a carrier pigeon, and give your intended recipients a reliable web address to check for updates. Betcha they’ve already heard about it anyway.

If the Internet world is about to collapse, clogged with gazillions of e-mail worms, the worst possible way to notify friends and family is by e-mail. D’oh! Pick up the phone, walk over to the water cooler or send a carrier pigeon, and give your intended recipients a reliable web address to check for updates. Betcha they’ve already heard about it anyway.

Try hard to be part of the solution, not part of the problem, okay? And if a friend forwards you a virus warning in an e-mail, do everyone a big favor: Shoot him a copy of the preceding bullet points, ask him to tape it to the side of his computer, and beg him to refer to it the next time he gets the forwarding urge.

Am I Infected?

So how do you know whether you’re infected?

The short answer is this: Many times, you don’t. If you think that your PC is infected, chances are very good that it isn’t. Why? Because malware these days doesn’t usually cause the kinds of problems people normally associate with infections.

Whatever you do, don’t fall for the scamware that tells you it removed 39 infections from your computer but you need to pay in order to remove the other 179 (see “Shunning scareware,” a little later in this chapter).

Evaluating telltale signs

Here are a few telltale signs that may — may — mean that your PC is infected:

![]() Someone tells you that you sent him an e-mail message with an attachment — and you didn’t send it. In fact, most e-mail malware these days is smart enough to spoof the From address, so any infected message that appears to come from you probably didn’t. Still, some dumb old viruses that aren’t capable of hiding your e-mail address are still around. And, if you receive an infected attachment from a friend, chances are good that both your e-mail address and his e-mail address are on an infected computer somewhere. Six degrees of separation and all that.

Someone tells you that you sent him an e-mail message with an attachment — and you didn’t send it. In fact, most e-mail malware these days is smart enough to spoof the From address, so any infected message that appears to come from you probably didn’t. Still, some dumb old viruses that aren’t capable of hiding your e-mail address are still around. And, if you receive an infected attachment from a friend, chances are good that both your e-mail address and his e-mail address are on an infected computer somewhere. Six degrees of separation and all that.

![]() You suddenly see files with two filename extensions scattered around your computer. Filenames such as kournikova.jpg.vbs (a VBScript file masquerading as a JPG image file) or somedoc.txt.exe (a Windows program that wants to appear to be a text file) should send you running for your antivirus software.

You suddenly see files with two filename extensions scattered around your computer. Filenames such as kournikova.jpg.vbs (a VBScript file masquerading as a JPG image file) or somedoc.txt.exe (a Windows program that wants to appear to be a text file) should send you running for your antivirus software.

Always, always, always have Windows show you filename extensions (see Book VI, Chapter 1).

Always, always, always have Windows show you filename extensions (see Book VI, Chapter 1).

![]() Your antivirus software suddenly stops working. If the icon for your antivirus product disappears from the notification area (near the clock), something killed it — and chances are very good that the culprit was a virus.

Your antivirus software suddenly stops working. If the icon for your antivirus product disappears from the notification area (near the clock), something killed it — and chances are very good that the culprit was a virus.

![]() You can't reach websites that are associated with anti-malware manufacturers. For example, Firefox or Internet Explorer or Chrome works fine with most websites, but you can't get through to

You can't reach websites that are associated with anti-malware manufacturers. For example, Firefox or Internet Explorer or Chrome works fine with most websites, but you can't get through to www.microsoft.com, www.symantec.com, or www.mcafee.com. This problem is a key giveaway for several infections.

Where did that message come from?

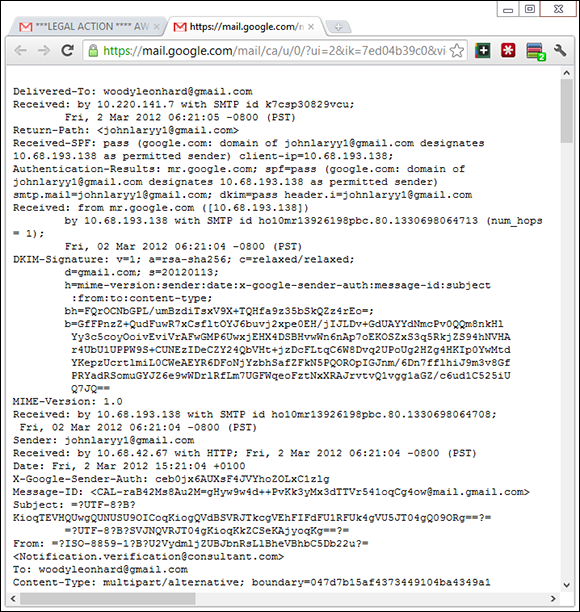

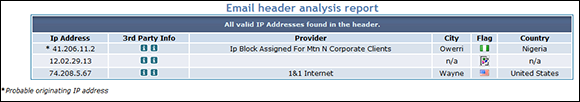

In my discussion of 419 scams, I mentioned that I can trace several scammer messages back to Nigeria. If you’ve never traced a message before, you’ll probably find it intriguing — and frustrating.

You know that return addresses lie. Just like an antagonist in the TV series, House. You can’t trust a return address because “spoofing” one is absolutely trivial. So what can you do?

If you receive a message and want to know where it came from, the first step is to find the header. In the normal course of events, you never see message headers. They look like the gibberish in Figure 1-8.

Figure 1-8: The header for the 419 message in Figure 1-7.

Here’s how to find a message’s header:

![]() If you’re using Outlook 2003 and earlier, open the message and then choose View⇒Options.

If you’re using Outlook 2003 and earlier, open the message and then choose View⇒Options.

![]() In Outlook 2007, you have to open the message and then click the tiny square with a downward, right-facing arrow in the lower-right corner of the Options group.

In Outlook 2007, you have to open the message and then click the tiny square with a downward, right-facing arrow in the lower-right corner of the Options group.

![]() Outlook 2010 and Outlook 2013 will show you the header, but only if you know the secret handshake. Open the message. In the message window, click File and then Properties. The header is listed in the box marked Internet eaders.

Outlook 2010 and Outlook 2013 will show you the header, but only if you know the secret handshake. Open the message. In the message window, click File and then Properties. The header is listed in the box marked Internet eaders.

![]() In Gmail, click the down arrow next to the message subject and choose Show Original. That shows you the entire message, including the header.

In Gmail, click the down arrow next to the message subject and choose Show Original. That shows you the entire message, including the header.

![]() In Hotmail or Outlook.com, click the down arrow next to Reply, which is near the sender and subject.

In Hotmail or Outlook.com, click the down arrow next to Reply, which is near the sender and subject.

Other e-mail programs work differently. You may have to jump on to Google to figure out how to see a message’s header.

After you have the header, copy it, and head over to the ipTracker site, www.iptrackeronline.com/header.php. Paste the message's header into the top box and then tap or click Submit Header for Analysis. A report like the one in Figure 1-9 appears.

Figure 1-9: Confirmation that a message came from Nigeria.

What to do next

If you think that your computer is infected, follow these steps:

1. Don’t panic.

Chances are very good that you’re not infected.

2. DO NOT REBOOT YOUR COMPUTER.

You may trigger a virus update when you reboot. Stay cool.

3. Run a full scan of your system. If you’re using Windows Defender, go to the Metro Start screen, type def, and choose Windows Defender.

If you aren’t using Windows Defender, get your antivirus package to run a full scan.

The Windows Defender main interface appears (see Figure 1-10). See Book IX, Chapter 3 for details about Windows Defender.

4. On the right, tap or click Full and then tap or click Scan Now.

A full scan can take a long time. Go have a latte or two.

5. If Step 4 still doesn't solve the problem, go to the Malwarebytes Removal forum at http://forums.malwarebytes.org/index.php?showforum=7 and post your problem on the Malware Removal forum.

Make sure that you follow the instructions precisely. The good folks at AumHa are all volunteers. You can save them — and yourself — lots of headaches by following their instructions to the letter.

6. Do not — I repeat — do not send messages to all your friends advising them of the new virus.

Messages about a new virus can outnumber infected messages generated by the virus itself — in some cases causing more havoc than the virus itself. Try not to become part of the problem. Besides, you may be wrong.

Figure 1-10: Windows Defender, ready for action.

Shunning scareware

A friend of mine brought me her computer the other day and showed me a giant warning about all the viruses residing on it (see Figure 1-11). She knew that she needed XP Antivirus, but she didn’t know how to install it. Thank heaven.

Figure 1-11: Rogue anti-malware gives you reason to pay.

Another friend brought me a computer that always booted to a Blue Screen of Death that said

Error 0x00000050 PAGE_FAULT_IN_NON_PAGED_AREA

It took a whole day to unwind all the junkware on that computer, but when I got to the bottom dreck, I found Vista Antivirus 2009.

Here’s the crazy part: Most people install this kind of scareware voluntarily. One particular family of rogue antivirus products, named Win32/FakeSecSen, has infected more than a million computers; see Figure 1-12.

Figure 1-12: Win32/FakeSecSen scares you into thinking you have to pay to clean your computer.

The exact method of infection can vary, as will the payloads. Almost always, people install rogue antivirus programs when they think they’re installing the latest, greatest virus chaser — and they’re hastened to get it working because they just know there are 179 more viruses on their computers that have to be cleaned.

If you have it, how do you remove it? For starters, don't even bother with Windows Add or Remove Programs. Any company clever enough to call a piece of scum Antivirus 2012 won't make it easy for you to zap it. Personally, I rely on www.malwarebytes.com — but removing some of these critters is very difficult (see Book IX, Chapter 4).

Microsoft has an excellent review of rogue antivirus products in its Security Intelligence Report Volume 6, available at www.microsoft.com/sir.

Getting Protected

The Internet is wild and woolly and wonderful — and, by and large, it’s unregulated, in a Wild West sort of way. Some would say it cannot be regulated, and I agree. Although some central bodies control basic Internet coordination questions — how the computers talk to each other, who doles out domain names such as Dummies.com, and what a web browser should do when it encounters a particular piece of HyperText Markup Language (HTML) — no central authority or Web Fashion Police exists.

In spite of its Wild West lineage and complete lack of couth, the Internet doesn’t need to be a scary place. If you follow a handful of simple, common-sense rules, you’ll go a long way toward making your Internet travels more like Happy Trails and less like Doom III.

Protecting against malware

“Everybody” knows that the Internet breeds viruses. “Everybody” knows that really bad viruses can drain your bank account, break your hard drive, and give you terminal halitosis — just by looking at an e-mail message with Good Times in the Subject line. Right.

![]() Don’t install weird programs, cute icons, automatic e-mail signers, or products that promise to keep your computer oh-so-wonderfully safe. Unless the software comes from a reputable manufacturer whom you trust and you know precisely why you need it, you don’t want it. Don’t be fooled by products that claim to clean your Registry or clobber imaginary infections.

Don’t install weird programs, cute icons, automatic e-mail signers, or products that promise to keep your computer oh-so-wonderfully safe. Unless the software comes from a reputable manufacturer whom you trust and you know precisely why you need it, you don’t want it. Don’t be fooled by products that claim to clean your Registry or clobber imaginary infections.

You may think that you absolutely must synchronize the Windows clock (which Windows does amazingly well, no extra program needed), tune up your computer (gimme a break), use those cute little smiley icons (gimme a bigger break), install a pop-up blocker (IE, Firefox, and Chrome do that well), or install an automatic e-mail signer (your e-mail program already can sign your messages — read the manual, pilgrim!). What you end up with is an unending barrage of hassles and hustles.

![]() Never, ever, open a file attached to an e-mail message until you contact the person who sent you the file and verify that she did, in fact, send you the file intentionally. You should also apply a bit of discretion and ask yourself whether the sender is smart enough to avoid sending you an infected file. After you contact the person who sent you the file, don’t open the file directly. Save it to your hard drive and run Windows Defender on it before you open it.

Never, ever, open a file attached to an e-mail message until you contact the person who sent you the file and verify that she did, in fact, send you the file intentionally. You should also apply a bit of discretion and ask yourself whether the sender is smart enough to avoid sending you an infected file. After you contact the person who sent you the file, don’t open the file directly. Save it to your hard drive and run Windows Defender on it before you open it.

![]() Follow the instructions in Book VI, Chapter 1 to force Windows to show you the full name of all the files on your computer. That way, if you see a file named something.cpl or iloveyou.vbs, you stand a fighting chance of understanding that it may be an infectious program waiting for your itchy finger.

Follow the instructions in Book VI, Chapter 1 to force Windows to show you the full name of all the files on your computer. That way, if you see a file named something.cpl or iloveyou.vbs, you stand a fighting chance of understanding that it may be an infectious program waiting for your itchy finger.

![]() Don’t trust e-mail. Every single part of an e-mail message can be faked, easily. The return address can be spoofed. Even the header information, which you don’t normally see, can be pure fiction. Links inside e-mail messages may not point where you think they point. Anything you put in a message can be viewed by anybody with even a nodding interest — to use the old analogy, sending unencrypted e-mail is a lot like sending a postcard. Those of you who live in the United States or send mail to or from the United States now know that Uncle Sam himself has been looking at all your mail — the NSA has been sharing the information with the DEA and IRS and lying about it (see the Forbes magazine series by Jennifer Granick).

Don’t trust e-mail. Every single part of an e-mail message can be faked, easily. The return address can be spoofed. Even the header information, which you don’t normally see, can be pure fiction. Links inside e-mail messages may not point where you think they point. Anything you put in a message can be viewed by anybody with even a nodding interest — to use the old analogy, sending unencrypted e-mail is a lot like sending a postcard. Those of you who live in the United States or send mail to or from the United States now know that Uncle Sam himself has been looking at all your mail — the NSA has been sharing the information with the DEA and IRS and lying about it (see the Forbes magazine series by Jennifer Granick).

![]() Check your accounts. Look at your credit card and bank statements, and if you see a charge you don’t understand, question it. Log on to all your financial websites frequently, and if somebody changed your password, scream bloody murder.

Check your accounts. Look at your credit card and bank statements, and if you see a charge you don’t understand, question it. Log on to all your financial websites frequently, and if somebody changed your password, scream bloody murder.

Disabling Java and Flash

I also salute the rapid change from Flash, for automating websites, to HTML5, which does a better job in a faster and more secure way.

Google’s browser Chrome has some serious malware-blocking capabilities, combined with custom-built Java and Flash engines that make surfing with Chrome (debatably) the safest choice of the Big Three.

Using your credit card safely online

Many people who use the web refuse to order anything online because they’re afraid that their credit card numbers will be stolen and they’ll be liable for enormous bills. Or they think the products will never arrive and they won’t get their money back.

If your credit card was issued in the United States and you’re ordering from a U.S. company, that’s simply not the case. Here’s why:

![]() The Fair Credit Billing Act protects you from being charged by a company for an item you don't receive. It's the same law that governs orders placed over the telephone or by mail. A vendor generally has 30 days to send the merchandise, or it has to give you a formal written chance to cancel your order. For details, go to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) website (

The Fair Credit Billing Act protects you from being charged by a company for an item you don't receive. It's the same law that governs orders placed over the telephone or by mail. A vendor generally has 30 days to send the merchandise, or it has to give you a formal written chance to cancel your order. For details, go to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) website (www.ftc.gov/bcp/edu/pubs/consumer/credit/cre28.shtm).

![]() Your maximum liability for charges fraudulently made on the card is $50 per card. The minute you notify the credit card company that somebody else is using your card, you have no further liability. If you have any questions, the Federal Trade Commission can help (

Your maximum liability for charges fraudulently made on the card is $50 per card. The minute you notify the credit card company that somebody else is using your card, you have no further liability. If you have any questions, the Federal Trade Commission can help (www.consumer.ftc.gov/articles/0213-lost-or-stolen-credit-atm-and-debit-cards).

The rules are different if you’re not dealing with a U.S. company and using a U.S. credit card. For example, if you buy something in an online auction from an individual, you don’t have the same level of protection. Make sure that you understand the rules before you hand out credit card information. Unfortunately, there’s no central repository (at least none I could find) of information about overseas purchase protection for U.S. credit card holders: Each credit card seems to handle cases individually. If you buy things overseas using a U.S. credit card, your relationship with your credit card company generally provides your only protection.

Regardless, take a few simple precautions to make sure that you aren’t giving away your credit card information:

![]() When you place an order online, make sure that you’re dealing with a company you know. In particular, don’t click a link in an e-mail message and expect to go to the company’s website. Type the company’s address into Internet Explorer or Firefox, or use a link that you stored in your Internet Explorer Favorites or the Firefox Bookmarks list.

When you place an order online, make sure that you’re dealing with a company you know. In particular, don’t click a link in an e-mail message and expect to go to the company’s website. Type the company’s address into Internet Explorer or Firefox, or use a link that you stored in your Internet Explorer Favorites or the Firefox Bookmarks list.

![]() Type your credit card number only when you’re sure that you’ve arrived at the company’s site and when the site is using a secure web page. The easy way to tell whether a web page is secure is to look in the lower-right corner of the screen for a picture of a lock (see Figure 1-13). Secure websites scramble data so that anything you type on the web page is encrypted before it’s sent to the vendor’s computer. In addition, Firefox tells you a site’s registration and pedigree by clicking the icon to the left of the web address. In Internet Explorer, the icon appears to the right of the address.

Type your credit card number only when you’re sure that you’ve arrived at the company’s site and when the site is using a secure web page. The easy way to tell whether a web page is secure is to look in the lower-right corner of the screen for a picture of a lock (see Figure 1-13). Secure websites scramble data so that anything you type on the web page is encrypted before it’s sent to the vendor’s computer. In addition, Firefox tells you a site’s registration and pedigree by clicking the icon to the left of the web address. In Internet Explorer, the icon appears to the right of the address.

![]()

Figure 1-13: Major browsers show a lock to indicate a secure site.

Be aware that crafty web programmers can fake the lock icon and show an

Be aware that crafty web programmers can fake the lock icon and show an https:// (secure) address to try to lull you into thinking that you're on a secure web page. To be safe, confirm the site's address and click the icon to the left of the address at the top to show the full security certificate.

![]() Don’t send your credit card number in an ordinary e-mail message. E-mail is just too easy to intercept. And for heaven’s sake, don’t give out any personal information when you’re chatting online.

Don’t send your credit card number in an ordinary e-mail message. E-mail is just too easy to intercept. And for heaven’s sake, don’t give out any personal information when you’re chatting online.

![]() If you receive an e-mail message requesting credit card information that seems to be from your bank, credit card company, Internet service provider, or even your sainted Aunt Martha, don’t send sensitive information back by way of e-mail. Insist on using a secure website and type the company’s address into your browser.

If you receive an e-mail message requesting credit card information that seems to be from your bank, credit card company, Internet service provider, or even your sainted Aunt Martha, don’t send sensitive information back by way of e-mail. Insist on using a secure website and type the company’s address into your browser.

Defending your privacy

“You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”

That’s what Scott McNealy, CEO of Sun Microsystems, said to a group of reporters on January 25, 1999. He was exaggerating — Scott has been known to make provocative statements for dramatic effect — but the exaggeration comes awfully close to reality. (Actually, if Scott told me the sky was blue, I’d run outside and check. But I digress.)

![]() Use work systems only for work. Why use your company e-mail ID for personal messages? C'mon. Sign up for a free web-based e-mail account, such as Gmail (

Use work systems only for work. Why use your company e-mail ID for personal messages? C'mon. Sign up for a free web-based e-mail account, such as Gmail (www.gmail.com), Yahoo! Mail (www.mail.yahoo.com), or Hotmail/Outlook.com (www.hotmail.com and www.outlook.com).

In the United States, with few exceptions, anything you do on a company PC at work can be monitored and examined by your employer. E-mail, website history files, and even stored documents and settings are all fair game. At work, you have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.

In the United States, with few exceptions, anything you do on a company PC at work can be monitored and examined by your employer. E-mail, website history files, and even stored documents and settings are all fair game. At work, you have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.

![]() Don’t give it away. Why use your real name when you sign up for a free e-mail account? Why tell a random survey that your annual income is between $20,000 and $30,000? (Or is it between $150,000 and $200,000?)

Don’t give it away. Why use your real name when you sign up for a free e-mail account? Why tell a random survey that your annual income is between $20,000 and $30,000? (Or is it between $150,000 and $200,000?)

All sorts of websites — particularly Microsoft — ask questions about topics that, simply put, are none of their dern business. Don’t put your personal details out where they can be harvested.

![]() Follow the privacy suggestions in this book. You turned off Smart Search already, right? (See Book II, Chapter 3.) You know that Google keeps track of what you type in to the Google search engine, and Microsoft keeps track of what you type in to Bing. You know that both Google and Microsoft scan your e-mail — and that Google, at least, admits to using the contents of e-mails in order to direct ads at you. You know that files stored in the cloud can be opened by all sorts of people, in response to court orders, anyway.

Follow the privacy suggestions in this book. You turned off Smart Search already, right? (See Book II, Chapter 3.) You know that Google keeps track of what you type in to the Google search engine, and Microsoft keeps track of what you type in to Bing. You know that both Google and Microsoft scan your e-mail — and that Google, at least, admits to using the contents of e-mails in order to direct ads at you. You know that files stored in the cloud can be opened by all sorts of people, in response to court orders, anyway.

![]() Know your rights. Although cyberspace doesn't provide the same level of personal protection you have come to expect in meatspace (real life), you still have rights and recourses. Check out

Know your rights. Although cyberspace doesn't provide the same level of personal protection you have come to expect in meatspace (real life), you still have rights and recourses. Check out www.privacyrights.org for some thought-provoking notices.

Keep your head low and your powder dry!

Reducing spam

Everybody hates spam, but nobody has any idea how to stop it. Not the government. Not Bill Gates. Not your sainted aunt’s podiatrist’s second cousin.

By and large, Windows is only tangentially involved in the spam game — it’s the messenger, as it were. But every Windows user I know receives e-mail. And every e-mail user I know gets spam. Lots of it.

Why is it so hard to identify spam? Consider. There are 600,426,974,379,824,381,952 different ways to spell Viagra. No, really. If you use all the tricks that spammers use — from simple swaps such as using the letter l rather than i or inserting e x t r a s p a c e s in the word, to tricky ones like substituting accented characters — you have more than 600 quintillion different ways to spell Viagra. It makes the national debt look positively tiny.

Hard to believe? See www.cockeyed.com/lessons/viagra/viagra.html for an eye-opening analysis.

Spam scanners look at e-mail messages and try to determine whether the contents of the potentially offensive message match certain criteria. Details vary depending on the type of spam scanner you use (or your Internet service provider uses), but in general, the scanner has to match the contents of the message with certain words and phrases stored in its database. If you’ve seen a lot of messages with odd spellings come through your spam scanner, you know how hard it is to see through all those sextillion, er, septillion variations.

![]() Don’t encourage ’em. Don’t buy anything that’s offered by way of spam (or any other e-mail that you didn’t specifically request). Don’t click through to the website. Simply delete the message. If you see something that may be interesting, use Google or another web browser to look for other companies that sell the same item.

Don’t encourage ’em. Don’t buy anything that’s offered by way of spam (or any other e-mail that you didn’t specifically request). Don’t click through to the website. Simply delete the message. If you see something that may be interesting, use Google or another web browser to look for other companies that sell the same item.

![]() Opt out of mailings only if you know and trust the company that’s sending you messages. If you’re on the Costco mailing list and you’re not interested in its e-mail any more, click the Opt Out button at the bottom of the page. But don’t opt out with a company you don’t trust: It may just be trying to verify your e-mail address.

Opt out of mailings only if you know and trust the company that’s sending you messages. If you’re on the Costco mailing list and you’re not interested in its e-mail any more, click the Opt Out button at the bottom of the page. But don’t opt out with a company you don’t trust: It may just be trying to verify your e-mail address.

![]() Never post your e-mail address on a website or in a newsgroup. Spammers have spiders that devour web pages by the gazillion, crawling around the web, gathering e-mail addresses and other information automatically. If you post something in a newsgroup and want to let people respond, use a name that's hard for spiders to swallow:

Never post your e-mail address on a website or in a newsgroup. Spammers have spiders that devour web pages by the gazillion, crawling around the web, gathering e-mail addresses and other information automatically. If you post something in a newsgroup and want to let people respond, use a name that's hard for spiders to swallow: woody (at) ask woody (dot) com, for example.

![]() Never open an attachment to an e-mail message or view pictures in a message. Spammers use both methods to verify that they’ve reached a real, live address. And, you wouldn’t open an attachment anyway — unless you know the person who sent it to you, you verified with her that she intended to send you the attachment, and you trust the sender to be savvy enough to avoid sending infected attachments.

Never open an attachment to an e-mail message or view pictures in a message. Spammers use both methods to verify that they’ve reached a real, live address. And, you wouldn’t open an attachment anyway — unless you know the person who sent it to you, you verified with her that she intended to send you the attachment, and you trust the sender to be savvy enough to avoid sending infected attachments.

![]() Never trust a website that you arrive at by “clicking through” a hot link in an e-mail message. Be cautious about websites you reach from other websites. If you don’t personally type the address in the Internet Explorer address bar, you may not be in Kansas any more.

Never trust a website that you arrive at by “clicking through” a hot link in an e-mail message. Be cautious about websites you reach from other websites. If you don’t personally type the address in the Internet Explorer address bar, you may not be in Kansas any more.

![]() Most important of all, if spam really bugs you, stop using your current e-mail program and switch to Gmail or Hotmail/Outlook.com. Both of them have superb spam filters that are updated every nanosecond. You’ll be very pleasantly surprised, I guarantee.

Most important of all, if spam really bugs you, stop using your current e-mail program and switch to Gmail or Hotmail/Outlook.com. Both of them have superb spam filters that are updated every nanosecond. You’ll be very pleasantly surprised, I guarantee.

Ultimately, the only long-lasting solution to spam is to change your e-mail address and give out your address only to close friends and business associates. Even that strategy doesn’t solve the problem, but it should reduce the level of spam significantly. Heckuva note, ain’t it?

You probably first heard about rootkits in late 2005, when a couple of security researchers discovered that certain CDs from Sony BMG surreptitiously installed rootkits on computers: If you merely played the CD on your computer, the rootkit took hold. Several lawsuits later, Sony finally saw the error of its ways and vowed to stop distributing rootkits with its CDs. Nice guys. (The researchers, Mark Russinovich and Bryce Cogswell, were later hired by Microsoft.)

You probably first heard about rootkits in late 2005, when a couple of security researchers discovered that certain CDs from Sony BMG surreptitiously installed rootkits on computers: If you merely played the CD on your computer, the rootkit took hold. Several lawsuits later, Sony finally saw the error of its ways and vowed to stop distributing rootkits with its CDs. Nice guys. (The researchers, Mark Russinovich and Bryce Cogswell, were later hired by Microsoft.) If you aren’t sure whether you’re being conned, ask the person on the other end of the line for your Microsoft Support Case

If you aren’t sure whether you’re being conned, ask the person on the other end of the line for your Microsoft Support Case