CHAPTER TWO

Generating Value in a World of Uncertainty

FROM THE MOMENT WE enter this world as a baby until the moment we depart, we are constantly faced with choices. Those choices may range from the inconsequential to those having tremendous, life-long impacts. Those impacts can extend from us individually, to those immediately around us, and in some cases to many others around the world. Choices also differ from those that are very simple to make to those that are exceedingly complex and multifaceted. Choices can be focused on high-level, long-term objectives such as the selection of a professional career or interest, a more near-term selection of a university degree or educational program that will enable the choice of professional career, or even more near-term choices such as which classes to take, which professor to sign up with, or how much to study for an upcoming exam.

In all cases, however, individuals seek one general outcome for all choices: to maximize the value of that choice, whether in the short term or the long term. For example, if asked whether a two-seater sports car or an SUV offered greater value, a family needing to transport children to after-school activities might logically view the SUV as offering greater value while the bachelor or bachelorette might choose the sports car as offering greater value. Value as used here does not refer to which costs more. Instead, it is related to the perceived return on investment. Only in cases where resources are unconstrained – a very unlikely scenario in the “real” world in which we live – does value reflect benefits absent consideration of resources consumed.

It is important to note that value is “in the eye of the beholder.” One individual or family will evaluate the value of a particular automobile differently than another individual or family. Parents may have different sets of criteria in determining value, as will the various children of the family. Similarly, organizations evaluate the value of the choices before them. However, while individuals make these decisions to support their self-interests, organizations must make decisions to maximize the value delivered to a much broader and potentially more diverse set of stakeholders.

Stakeholder interests in private sector companies must be considered and balanced as a whole, because many – sometimes in conflict with one another – can be key to the organization's success. For example, shareholders seek a good return on their financial investment; customers seek value for money in the products or services they purchase; regulators seek compliance with laws and regulations; and employees seek competitive compensation, good working conditions, and potential for advancement.

However, as diverse as these various stakeholder interests may be, public sector stakeholders in government can be considerably greater in number and even more diverse. Public sector agencies seek to meet citizens and taxpayer expectations, meet the needs of beneficiaries of particular services, comply with guidance from legislative bodies, and respond to many other stakeholder demands. Moreover, stakeholders of a public sector entity can have very divergent interests and expectations, thereby resulting in very different perceptions of what constitutes “value.” Just a single government agency at any level (e.g., federal, regional, municipal), for example, may have to deal with multiple funding committees with very divergent interests and definitions of “value.” This makes the articulation of overall value for a government agency's combined portfolio of products and services typically much more challenging in the public sector than in the private sector.

The authors reject the statement made by some employees in government who say, “We are not a business.” This is shortsighted. It is true that unlike commercial companies, public sector organizations cannot choose their customers and their goal is not to make a profit. But what else is different compared to a commercial company? Just like private sector organizations, government agencies and departments are responsible to attempt to optimize their resources and align them with the policies and strategies of their executive team, all with the purpose of best serving their citizens.

Today, public sector organizations are behaving more like businesses. They are converging with commercial companies in the ways they adopt businesslike improvement methods, such as Six Sigma quality and lean management practices. Many case studies from the private sector cite that using modern management methods has elevated a company's industry rankings and provided increased profits, market share, and customer satisfaction. Government agencies and departments can also expect improved service levels and financial performance.

DEFINING VALUE

We noted that the fundamental management challenge facing any organization is to consistently make decisions that increase, and ideally maximize, organizational stakeholder value. However, while organizations can discuss the importance of generating stakeholder value for achieving success, that discussion will remain largely philosophical until one defines more precisely what is meant by “value.” We began this discussion by suggesting that value was a function of both benefits or results achieved and the costs or resources consumed in achieving those benefits. We can define this as Value = Results achieved/Resources consumed.

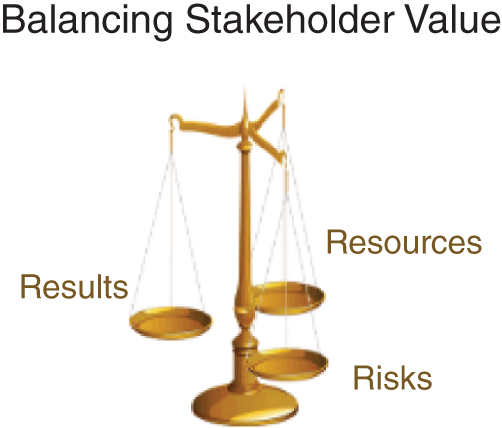

However, at what point do we calculate benefits and costs? In a world of uncertainty, the projected value at any point in time is subject to change. This is because there is some level of uncertainty at the point in time when any initial decision is made to take action to achieve a future result. We thus need to add to this tradeoff a consideration of risk. Evaluation of stakeholder value therefore becomes a three-way balancing act, as depicted in Figure 2.1.

FIGURE 2.1 Balancing stakeholder value.

Source: © Douglas Webster. Used with permission.

All organizations are accustomed to considering the tradeoffs of results to be achieved for a particular level of resources invested. However, too often the analysis leading to a decision stops with a cost-benefit analysis at a point in time. There is no in-depth analysis of the risks faced regarding either the achievement of desired objectives, or the ability to deliver those objectives within the predicted level of resource requirements. Effective management requires that risk not be a minor consideration, or worse yet, a mere afterthought. The element of risk must be analyzed as thoroughly as the elements of results delivered and resources required. Only with a three-way analysis of results, resources, and risks can a decision maker expect to truly understand the options that offer greatest potential value. The importance of risk management will become even more important as we discuss the critical need to operate in a world of constant change.

As was noted, stakeholders define what constitutes value in ways that may be unique to them. However, the criteria for this determination can be generally thought of as a need to balance these three specific considerations. To summarize:

- Results as used in this discussion are those outputs and outcomes of any decision. That decision may be to deliver any one of thousands of services provided to citizens and taxpayers, complete projects or transactions required to run an organization, satisfy employee needs, and so on.

- Resources are those financial assets, nonfinancial assets (such as facilities and physical assets), time (of employees or others), and other elements of limited availability required to achieve a result.

- Risks are the uncertainties associated with achieving the results sought, the ability to achieve those selected results with budgeted resources, or both.

MAXIMIZING VALUE

An organization delivers value by achieving desired results with available resources while recognizing and managing the associated risks. Organizations maximize that value when they balance considerations of results, resources (or costs), and risks in a manner that best meets the overall interests of key stakeholders. This is conceptually depicted in Figure 2.2.

This simple need to balance results sought, resources committed, and risks accepted is certainly not completely new thinking. Investors, for example, seek to maximize a return on investment for a particular level of risk that is deemed acceptable. This is illustrated in Figure 2.3.

FIGURE 2.2 Maximizing stakeholder value.

Source: © Douglas Webster. Used with permission.

FIGURE 2.3 Risk-adjusted ROI.

Source: © Douglas Webster. Used with permission.

VBM brings the following to the management conversation:

- Results, resources, and risks must all be interactively balanced.

- Stakeholder interests can be diverse and internally in conflict, and maximum value generation requires balancing potential conflicts.

- VBM requires a portfolio management approach across the organization.

Balancing Results, Resources, and Risk

All three elements (results, resources, and risks) are equally important in choosing the optimal solution. While results and resources are almost always considered, risk is far too often treated as an afterthought unless high levels of risk are immediately apparent. Moreover, risk is not simply a “gate” through which decisions otherwise already made must pass if value is to be maximized. The challenge is not simply to make a decision with an “acceptable” level of risk, but rather a decision in which the level of accepted risk directly contributes to offering the maximum potential stakeholder value. Risk is no longer thought of as only a negative factor that must be avoided to the extent possible. Instead, it is viewed as a balancing factor recognizing that taking on greater risk can in some cases allow for the achievement of opportunities that might otherwise be lost, or allowing limited resources to be redeployed to other areas that may offer greater value.

Balancing Stakeholder Interests and Values

Achieving maximum stakeholder value requires explicit recognition of the diversity of stakeholder interests typically found in any organization. The goal is not to select a primary stakeholder and focus solely on their definition of value, but to consider all stakeholder needs and determine a balance among those needs that best meets the organization's mission, vision, and strategy.

The ideal balance of results, resources, and risks for one set of stakeholders may be considerably different than for another set of stakeholders. Shareholders of commercial companies, for example, typically seek a return on their financial investment at equal or better risk-adjusted rates than they might have available elsewhere. Employees of those same companies seek competitive compensation, satisfying working conditions, and potential for advancement. Customers seek value for money in the products or services they purchase, and regulators seek compliance with laws and regulations. Moreover, while these generalizations may characterize groups of stakeholders in general, there can be great diversity even among stakeholders of any one particular group.

A Portfolio Perspective

Portfolio management at the enterprise level in balancing considerations of results, resources, and risks is perhaps the most significant addition of VBM to traditional management practices. The ultimate goal of VBM is not to maximize value for any one particular part of the organization, but rather for the organization as a whole. Organizations must therefore consider their business decisions in making tradeoffs among results, resources, and risks from an overall portfolio perspective.

Managing a portfolio of options to maximize overall stakeholder value is much like an investor seeking to maximize the value of an investment portfolio. An investor may invest in stocks, bonds, real estate, and various other options, and even leave some funds in cash. Such decisions are driven by a desire to manage the overall balance between return on investment and the level of risk reflected in the investment portfolio.

Viewing management tradeoff decisions for the overall organization from a portfolio management perspective of course means that all business units, functions, and other organizational partitions must be considered collectively in the balancing of results, resources, and risks. Seeking to maximize overall organizational value does not mean that subordinate parts of the organization do not consider actions they need to take to maximize value at their level. What it does mean, however, is that they are ready to adjust those decisions, resulting in less value for their particular undertaking or part of the organization, if doing so allows for reallocation of results, resources, or risks for the greater good of the overall organization. VBM thus explicitly recognizes that some programs, organizational units, or individual decisions may face suboptimization at the local level in order to contribute to greater value at the enterprise value. Isolation any one part of the organization from such discussions invalidates the essential portfolio view of VBM.

It might be, for example, that reducing resources to one part of the organization will suboptimize the potential value from that part of the organization, but the redeployment of those resources to another part of the organization increases the overall value of the organization as a whole.

It is critical to note that the need to maximize value applies at any level of the organization. Needless to say, executive levels must consider the strategic consequences of their decisions to balance results, resources, and risks. However, every decision maker at every level of the organization must be motivated to maximize value from their part of the organization. The need to balance results, resources, and risks is not limited to a particular level of the organization – it is in fact an inherent part of any management decision at any organizational level. Moreover, aligning the entire organization in pursuit of maximum stakeholder value means that there must also be an integration of requirements and capabilities vertically across the organization. This will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter, but it is important to note that creating a true portfolio management approach across the organization is not something required only of the executive team. It is an enterprise-wide imperative.

BUILDING AN ORGANIZATIONAL STRATEGY TO DELIVER VALUE

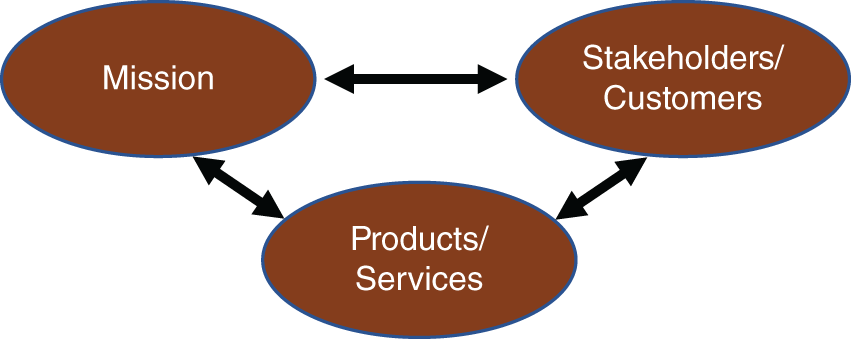

Recognizing the critical importance of stakeholder value to any organization is simply a starting point. Delivering that value requires a number of organizational capabilities, competencies, and actions. The first of these is development of a strategy and strategic planning process that recognizes the importance of aligning three considerations: (1) the organization's mission, (2) the products and services delivered by the organization consistent with that mission, and (3) the alignment of diverse stakeholder interests with both the mission and the organization's selected products and services. This three-way tradeoff must balance a variety of considerations that hopefully guide the achievement of maximum organizational value delivery. This interplay of considerations can be depicted as shown in Figure 2.4.

In the private sector, any of these may potentially be the starting point for establishing an organization. As one example, an inventor or innovator may create a product or service that he or she believes will “set the world on fire.” They may use this vision of a particular product or service to establish a mission of meeting a particular customer need consistent with certain organizational values, such as social responsibility considerations. Once these are defined at a high level, they may further consider investor needs, regulatory needs, subclasses of customer needs, employee needs, and other stakeholder needs.

FIGURE 2.4 Guiding organizational value.

Source: © Douglas Webster. Used with permission.

As an alternative example, a group of individuals may decide to go into commercial banking because they perceive a general opportunity with an above-market financial rate of return. They are not necessarily seeking to employ a new product or service, but seek a competitive advantage through lower cost of operations or other means.

It is thus not essential that a strategy first start with mission, stakeholder analysis, or selection of the products and services to be delivered. However, it is required that all three be considered as part of a balancing act that creates a strategy delivering maximum stakeholder value. Once an initial strategy is established, however, the focus on the influencing drivers of revised or updated strategy may shift over time. For example, if an investor envisions a completely new product or service that has the potential to transform society, that product or service may be the starting point for discussions of tradeoffs in defining mission and multiple stakeholder interests. However, once an organization is established to deliver that product or service, with a clearly articulated mission, and while meeting various and potentially conflicting stakeholder interests, those considerations may easily shift over time. If, for example, the product or service remains leading edge after a year or two, but regulators take notice and begin to focus on that product or service with new and unique regulatory oversight, stakeholder interests may take a much larger role in guiding future strategy.

Research indicates that the majority of strategies fail to be executed effectively – a fact that is potentially the cause of increasing involuntary CEO turnover rates and validated by shorter CEO job tenures with commercial companies. One can conclude that developing a great strategy is not the problem; however, executing the strategy is. What is needed is an understanding of the required modern management methods not only to identify a strategy, but also to bring it to fruition. The same goes for government agencies to deliver on their mission and policies.

The need to balance mission, stakeholder interests, and the products and services provided by the organization (as illustrated in Figure 2.2) is not to suggest any particular order of analysis. The interplay between these three factors will be unique to each organization and may certainly shift over time. However, none of the three should ever be totally ignored in any organization seeking to maximize stakeholder value.

It should also be noted at this point that while the above is a general description of factors to be balanced in maximizing stakeholder value, the diversity of those interests is typically greater in the public sector than in the private sector. Key government stakeholders include beneficiaries receiving services from the agency (e.g., citizens), taxpayers who are funding the delivery of services, and legislative bodies that provide the funding needed to run the agency and provide services. Reaching an understanding of key interests from any one stakeholder body can be challenging.

As an example, in the US federal government, a single agency can have multiple legislative committees overseeing operations, prioritizing agency goals, establishing specific program requirements, and providing funding. Each committee can have subcommittees, and all of these legislative bodies can establish different priorities for different parts of the agency. Adding to this great diversity of stakeholder interests, there will typically be great diversity of stakeholder interest even within a single committee dealing with a specific part of an agency. A universal challenge for any decision maker is to understand the diversity of needs in relevant groups of stakeholders, and this challenge is often greater for public sector decision makers than for their private sector counterparts.

BUILDING UPON A STRATEGY

The Cheshire Cat in Lewis Carrol's Alice in Wonderland had an exchange with Alice that has long been paraphrased as “if you don't know where you're going, any road will take you there.” Knowing where you are headed is certainly the first requirement in undertaking any journey. The strategic planning process establishes strategic goals and objectives that set direction for the organization. However, once you know where you are headed, thought must obviously be given to how you will get there.

This requires translating or decomposing strategic goals of value to stakeholders into operational objectives for the overall organization. These goals and objectives are in turn decomposed and cascaded downward to lower organizational levels that are focused on delivering more specific elements of the higher-level objectives. This can be conceptually represented as shown in Figure 2.5. Whether evaluating the current capabilities of an existing organization or considering the capability requirements of a newly created organization, careful thought must be given to: (1) how higher-level requirements get decomposed and communicated down to lower levels of the organization, and (2) how existing as-is or need-to-be organizational capabilities and capacity are aligned to meet the delegated requirements.

While top-level organizational goals and objectives must be cascaded downward to derive subobjectives to be achieved by lower-level organizational components, it is critical to recognize that the capabilities of every part of the organization, regardless of the organizational level, must be aligned to deliver existing capability to meet those designated goals.

FIGURE 2.5 Moving from goal setting to execution.

Source: © Douglas Webster. Used with permission.

Setting direction for an organization obviously accomplishes little if the organization lacks the capability to deliver on meeting the defined objectives. It is thus a two-way conversation between adjoining levels of organization management to ensure that capabilities at any level of the organization are sufficient and fully leveraged to meet the objectives that are passed down to that organizational level. Through a two-way dialog between adjoining organizational levels, objectives can and should be fine-tuned based on the capabilities of the organization to deliver on those objectives, and organizational capabilities can be fine-tuned based on the objectives that are established for it. Through this iterative process across organizational levels:

- Stakeholder value can be maximized at each level of the organization – and ultimately for the overall organization as a whole – by having managers come together with their direct reports and engaging collaboratively in discussing the balancing of requirements and organizational capabilities.

- Simultaneous balancing is possible of results sought, resources allocated, and risks to be assumed.

- Lower-level objectives can be identified that must be accomplished in order to successfully achieve higher-level objectives.

SUPPORTING THE DECISION-MAKING PROCESS WITHIN APPROPRIATE LIMITATIONS

The pursuit of operational objectives derived from and consistent with strategic goals and objectives must thus be facilitated through the cascading of subobjectives consistent with organizational capabilities, and while balancing results, resources, and risks in a manner that maximizes stakeholder value. However, decision makers who seek to accomplish such an approach to decision-making must have the appropriate processes in place supported by the necessary data. These processes will be explored in detail in the book, but they will include what the authors refer to as the three Rs:

- Result objectives management for achieving results of outcomes, outputs, and processes

- Resources and cost management, with cost-informed financial budgeting

- Risk management and the role of Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) to integrate risk considerations across the enterprise

It must also be noted that the need to balance results, resources, and risks is not without some limitations. Decisions should in all cases comply with legal and business ethics considerations. While some individuals may consider such compliance as a risk consideration, the authors believe that compliance with laws and sound business ethics must always be viewed as constraints within which stakeholder value tradeoff decisions are made.

PROVIDING REQUIRED DATA FOR APPROPRIATE DECISION-MAKING

In addition to having the required decision-making processes for maximizing stakeholder value by balancing results, resources, and risks, the relevant data must exist and be collected, validated, distributed, and used as appropriate in the decision-making processes. In many cases this requires appropriate information technology. Depending on the nature of data required for the organization's decision-making processes, organizations can potentially benefit from a multitude of techniques and technologies, including:1

- Decision algorithms: An algorithm is a procedure with a rigorous design. They can be used to make decisions or aid human decision-making.

- Search applications: A tool that searches a large repository of information such as the internet or a corporate knowledge management system.

- Data analysis tools: Tools that support statistical analysis of data sets.

- Reporting tools: Technologies that allow you to design and generate ad hoc or regular reports.

- Data analytics: Analytics is the automated discover of meaning in data. In many cases, analytics software is specific to a particular domain such as the analysis of web traffic data. The benefit of analytics is that users don't have to understand the underlying data and statistical models to obtain useful reports.

- Information visualization: A generic term for technologies that automatically visualize data or support human-driven design of information visuals.

- Data mining: Analysis of large sets of historical data typically using statistical models.

Technology barriers are an impediment to delivering stakeholder value. Causes for this are the lack of systems integration from various software vendors or homegrown legacy systems and from insufficient decision support information despite, in some cases, substantial raw source data. A simple way of describing this condition is that organizations are drowning in data but starving for information. This is one reason that the application of analytics, including leveraging Big Data, for insights on which to take actions is emerging as an important competency for all organizations to achieve.

The role of information technology will be described in Part Seven.

MANAGING THE ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE

Decisions can be made, but translating those decisions into sustainable actions can be challenging. Evidence abounds that attempted changes internal to organizations have a high risk of failure due to an organization's inability to implement and maintain new direction by the employees and others on whom the change is dependent.

A major obstacle to adopting or successfully implementing organizational improvement initiatives is cultural resistance to change. Another significant obstacle is that internal departments do not share information or collaborate. Combined, these two obstacles imply fear of being held accountable for results. A third obstacle is when the executive team's policies and strategy are insufficiently communicated to their managers and employees.

While not the focus of this book, the critical importance of organizational behavioral change management in making significant change within any organization will receive further discussion in Part Eight.

GOVERNING THE VALUE-BASED MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK

Pulling all of the above considerations together requires a governing process that ensures the organizational leadership collaborates to guide the organization toward maximizing value. This requires a communications and decision-making process that aligns and coordinates decisions intended to maximize value vertically from the top of the organization to the lowest levels – from the top desk to the desk-top. It also requires a decision-making process that coordinates laterally across the organization in a manner that eliminates silos of self-interest and a willingness to subordinate local interests for the greater organizational good.

For such a governance process to be effective in maximizing organizational value, it must integrate all of the elements of the value-based management (VBM) framework. This includes the governance of selected objectives and subobjectives, as well as the elements of results (performance), resources, and risks that must be balanced to maximize value. These are the three scales in Figure 2.1.

As a result, the financial budgeting process allocating resources, establishment of program performance targets, and the risk management governance process must all link together to ensure decisions made are done so fully recognizing the risk-adjusted cost-benefit of those decisions.

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

To summarize the above points, we offer the value-based management model, or the “House of VBM,” in Figure 2.6.

Here are the building blocks of the “House of VBM”:

- “The Goal” at the top of the house is what government organizations should aspire to: to maximize value for stakeholders.

FIGURE 2.6 Managing organizational value.

Source: © Douglas W. Webster. Used with permission.

- “The Direction” is from Figure 2.2. It involves governance to oversee and guide the alignment of organizational mission, understanding and balancing of stakeholder needs, and delivery of products and services meeting those stakeholder needs

- “The Mechanism” is from Figure 2.1. It includes the enterprise performance management (EPM) methods in the ellipse in the floor. The EPM methods contribute to the balancing of the three scales in Figure 2.1. The EPM methods, described in the Chapter 3, are continuously interacting to balance and improve the three scales: the three Rs, results, resources, and risks. This is where decision-making occurs.

- “Technology Enablers” involve information technology (IT) that supports the modeling and calculations used by ERM and the EPM methods (including resources and cost management).

- “The Foundation” is recognition that the core of any organization is its culture. Those people must have the understanding, motivation, skills, and abilities to execute and manage the components of the VBM framework. In many cases this will require a cultural shift in the organization.

The remainder of this book will focus further on exploring the components of this value-based management model, particularly as it relates to governmental agencies. The following list outlines where the VBM components will be further described in each part of the book:

- Part Two, “Strategy Management and Governance,” resides in the box labeled “The Direction”.

- Part Three, “Enterprise Performance Management,” discusses the means of integrating the three Rs.

- Part Four, “The Three Rs: Risk, Results, and Resources,” investigates the three Rs displayed in “The Mechanism.” The first chapter in this part explores risk management's role in helping balance considerations of results sought and resources allocated, along with the role of enterprise risk management in enabling a portfolio view of risk that helps maximize value across the organization. The other two chapters in this section discuss the EPM methods in results management, and managerial accounting practices, including (1) activity-based costing (ABC) to calculate the costs of services and outputs, and (2) capacity-sensitive driver-based budgeting and rolling financial forecasts.

- Part Five, “Management Accounting in Government,” consists of six chapters. Management accounting provides VBM resource information in the language of money. It explains activity-based costing (ABC) as an effective way to report the costs of outputs, including their per-unit cost. It explores driver-based budgeting and rolling financial forecasts, and concludes by describing how an ABC system can be implemented in weeks, not months, using a rapid prototyping implementation method.

- Part Six, “How Information Technology Impacts VBM” – residing in the “Technology Enablers” foundation – will address the role of technology in facilitating the execution of the methods and processes used in results management, resources management, and risk management to maximize stakeholders.

- Part Seven, “Influencing Behavior for VBM.” As noted above, the Foundation of the VBM framework is a capable, motivated, and empowered workforce. While some organizations may already have a workforce able to execute the VBM framework, most organizations will require changes in that workforce. These changes will include: (1) development of understanding of the framework and implications for individual work activities, (2) motivation to become part of the revised organization and processes, (3) developing competencies in the use of new processes and methods, and (4) becoming a learning and growth organization that constantly seeks improvement in the delivery of value.

- Part Eight, “The Future,” describes the future of VBM that the authors envision with adoption of the VBM methodology and mindset.

The next two chapters in Part Two will describe strategy management and governance residing in the box labeled “The Direction” in Figure 2.6.