Customer Value-Add and Its Impact on Revenue

…value is the primary influence on purchase decisions and the leading indicator of revenue growth, profitability, and competitive advantage.1

Customer value-add is the complete set of features and benefits provided by a good or service. What makes any feature or benefit value-added is the fact that a consumer is making a choice to sacrifice time and money and take on inherent risk to obtain the good or service. As we have seen in the previous chapter, though, when we take the concept of value-add inside the organization, we have to recognize that value is created through a series of activities. In addition, even inherently value-creating activities can contain some levels of business value-add and waste. Separating the value-adding aspects of business activities from their counterparts is the objective of value-based cost management systems (VCMS).

The literature on value creation has two primary foci: customers and shareholders. While it is clear that organizations create value for their shareholders when they make a profit, it is obvious that no shareholder value can be created unless some consumer need is met. Value capture references the ability of a firm to seize the largest share of the total value created for the consumer within the industry value chain. Throughout this book, the emphasis is on the consumer. Customers are defined as being end users who actually establish the monetary value of the products and services offered by firms in a value chain. Having clarified the focus of the discussion, let’s now turn to the concept of value attributes.

Defining Value Attributes

The key challenge for a successful business is to understand customer needs. In the current global and intensely competitive environment, it is more important than ever to both understand, and leverage, the relationship between customer requirements (value) and the costs and competencies required to meet these expectations.

A customer-focused organization understands the central role played by its value proposition in defining the firm’s overall revenue potential. A product’s economic value can be defined as the price of the customer’s best alternative (reference value) plus the value of attributes that differentiate the product from its alternatives.2 To understand value from the customer’s perspective is to gain the power to grow the top line of the business, a firm’s revenues which are essential to sustainable growth. While marketing and sales functions have used customer value information to target and effectively position a firm’s products and services within specific customer segments, this knowledge is not as consistently used to discipline the firm’s spending on resources and activities—its cost structure. The result is the cost–value gap, a schism between the market and the firm that if left in place can destroy both a company’s profits and its future.

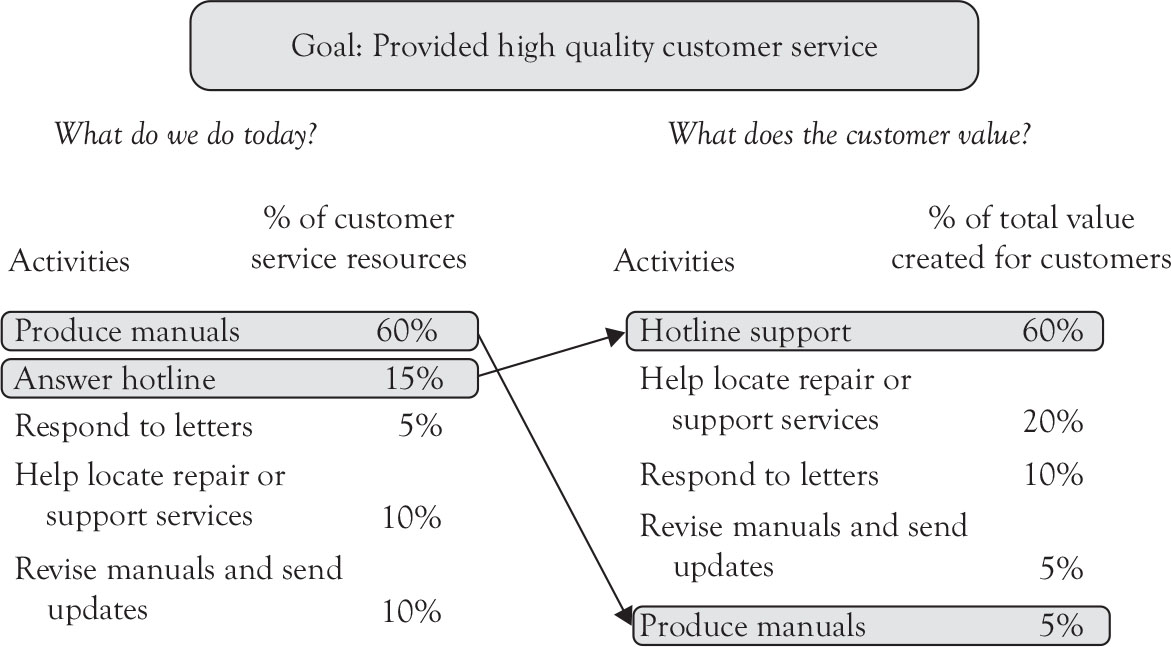

The cost–value gap is the difference between customer preferences for specific product or service features, called attributes, and the cost of the product being offered by the firm. A simple illustration of this gap as identified at a large electronics firm is presented in Figure 2.1.3 On the left side of the illustration is a list of the five primary activities completed by the firm’s customer service group, along with the percentages of the total customer service budget spent on each activity. As can be seen, producing and revising manuals consumes 70% of the total customer service budget, with direct contact customer service activities comprising the other 30% of the budget.

Figure 2.1. The cost–value gap.

Looking at the firm from the customer’s perspective, a very different picture of the importance of the firm’s service activities emerges. Specifically, manual availability and updates represent only 10% of the total service value proposition. Direct contact customer service activities are what the customer values, as evidenced by the 90% combined weighting of these activities by the firm’s customers. In the customers’ eyes, 89% of what the firm spends on manuals is waste.4 The company has failed to align its resources and activities with customer value preferences, and thereby reduced its potential amount of profit.

Activities in the right column of Figure 2.1 could be defined as overall service responsiveness. What the list of activities shows us is that we need the detail we get from an activity analysis, combined with the logic of the VCMS, to really operationalize this attribute in a way that allows the company to improve its service responsiveness. Companies cannot identify which activities are value-adding without understanding the relative importance of specific features/attributes valued by the customer. Bringing the customer’s perspective into the equation is always the essence of managing a customer-driven organization.

What this example illustrates is the fact that value attributes are themselves composed of a variety of value activities that the firm performs in order to meet customer expectations. Unless a firm has a clear understanding of what customers expect in terms of service responsiveness, they could be spending significant sums of money on performing a variety of activities without delivering what is desired by the customer. This is a lesson that has been learned in the design for manufacturability movement—that including the customer’s perspective provides the firm with the necessary knowledge to define exactly what a specific attribute means in actionable terms.

To be considered a value-added activity, then, the activity has to be one that customers value and are able to evaluate in terms of its impact on their ultimate satisfaction with a product or service. Value-added is an external, customer-driven perspective.

The Value Proposition

The entire list of features and capabilities offered by a firm’s product is its value proposition. This proposition is established during the design phase and can be very hard to change once the product or service is launched. Services are more responsive to the need to make downstream changes, but there is always a lag in terms of getting the focus to match customer expectations. It is expensive and time-consuming to try to correct the value proposition offered by a product/service bundle. It is critical to include the customer as soon as possible in the design phase so the resulting product actually hits its market target.

What is a value attribute, then? It is a specific feature of a product or service that the customer recognizes and places value on when making a purchase decision. Products and services create value for customers in a variety of ways: ease of use, performance, quality, service responsiveness, fashion sense, etc. It is important to understand that the customer and not the firm is the judge of whether these attributes create customer value and better satisfy his/her needs. When a bundle of value attributes is combined in a final good or service, a company establishes its value proposition.

In our field work, we have found that managers often don’t have an accurate view of customer preferences or the weight of their importance in customer decisions. Becoming a customer-driven organization means the customer plays an active role in all product/service decisions. The first order of business, then, is to include the customer perspective early in the process of developing a product’s or service’s value proposition.

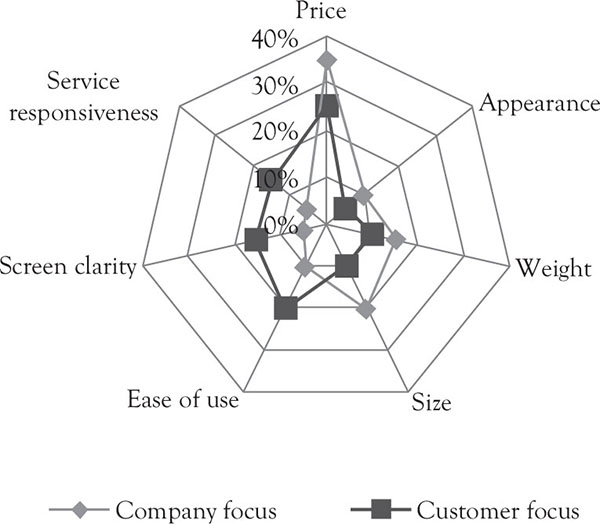

When we look at the entire value proposition of a firm, we usually end up with a list of five to eight items the customer cares about. If we add to this information how important each attribute is to the total value provided by a product or service, we can end up with a spider chart that looks something like Figure 2.2. This is the list of value attributes for a typical cell phone.

Figure 2.2. A spider’s view of value.

Notice that this chart has a very specific characteristic—all of the weights assigned to the value attributes add up to 100%. Why is this important? It is the critical assumption required to transform the attribute data into something that can be used in the accounting framework. Accounting has to add up. Any accounting system that doesn’t “balance” is unlikely to receive strong support from senior members of the management team, who remember this lesson very well from their basic accounting classes.

In developing and designing a VCMS, then, it is important to link together key marketing managers with the financial analysis people who are given responsibility for the revenue and cost aspects of the model. This is where the common language component of the VCMS originates. Different functional areas in the organization, specifically marketing and finance, have to agree on the language and focus when collecting customer information using the same metrics, ones that can bridge the gap between different areas of the firm.

Different methodologies exist for obtaining information on the valuation of customer attributes. Conjoint analysis has the objective of capturing the value of trade-offs in product features in a systematic way and to assign monetary value to specific attributes. Customers are presented with choices of similar products whose prices and features are different and are forced to choose a product they prefer. For technical and industrial products it is often possible to accurately measure the value of attributes by quantifying such features as reduced failure rates, and reduced labor costs, which then allows the firm to compute the value of the feature. Other customer value assessment tools, which are often used for value quantification, are indirect surveys, customer focus groups, and importance ratings.

Vague references to “important” versus “not important” cannot provide the specificity required to link accounting information to the marketing perspective. Having customers assign specific weights to attributes is a small adjustment to marketing analysis with major benefits for the firm. And, customers can provide this information—they inherently weight each value attribute when they are making their purchase decisions. Once monetary values are determined for the features for each identified market segment, the whole organization benefits by understanding exactly what and how much value each type of customer places on what the organization is producing. Marketing gains from this approach as it provides stronger metrics to use in the marketing models used to perform segmentation analysis. It is a change that is for the best for all involved parties, including the customers who ends up with a supplier that is much more knowledgeable about what they value and why.

Price and the Value Proposition

Customers make purchase decisions based on economic value and price paid compared with internal reference prices. The internal reference price is the price level that is expected to be “fair” for the product category.5 Customers form internal reference prices over time and they tend to frame actual purchase decisions and actual prices relative to this reference price. Reference price represents something best thought of as “table stakes.” It is the commodity nature of the product—features that all products in this market have to have to even be considered by a customer in the purchase decision.

Going back to our window example, price can be connected to the basic features of any window. It has to let in light but keep out the elements. These basic features of a window are non-negotiable. A window that doesn’t let in light or that fails to keep the rain out of the house would not be considered by a customer—at least not by many. Price, then, lays down the reference/commodity baseline for a product class, including all of the things that the product or service has to be able to do.

What are the table stakes for a cell phone? It has to be able to send and receive phone calls, and in today’s world, text messages and video clips. To do this effectively, a cell phone needs some basic electronics and a good antenna. If the phone can’t meet the basic requirements of the consumer it won’t be considered in the purchase decision. The challenge for a company is to understand exactly what features, and in what amounts, are critical for a product to be considered as a competitive offering. While this basic list will vary by customer type, it is also quite likely that customers that expect more from the product will be willing to pay a higher price for a differentiated offering.

In other words, price plays a key role in the strategic sense. It helps a company separate out those features that have to be in a basic offering that is positioned to compete on price alone versus a product or service that commands a premium in the market because it does something extra that the customer values. A company with an undifferentiated product will see most of the weighting in its customers’ value proposition collapse into a reference price. This is a difficult competitive position to maintain, as cost cutting becomes the only way to increase profits. It’s hard to grow the top line in an industry where products have become commodities.

Price, then, is defined by basic features, the baseline for a product to even enter into any customer’s purchase decision. The lower price is in the total weighting of attributes, the more important it is for the firm to differentiate itself on other features of the product or service. Knowing the table stakes of the competitive game is the first step in creating superior customer value. Throughout this book, price will be used to refer to the reference price, or table stakes element of the given product or service. This usage is made because in almost all the customer data efforts undertaken by the firms studied, the customers included price in their definition of key attributes.

Tying Value Creation to Revenue

The key innovation contained in the VCMS is the tying of value creation to specific revenue streams. The model makes the simple assumption that customer value identification results in actual revenue, transforming and strengthening the linkages between products and profits in the firm. Optimizing a firm’s profits begins with recognizing that a firm is not, by definition, given a “right” by the market to cover its costs. Instead, it must earn its revenues by meeting customer requirements better than the competition. If costs are kept within the boundaries of the price envelope, then there is profit. Profit is not guaranteed to any firm. This leads to several observations:

• Only by understanding and investing in building the value-added core of activities can a firm increase its “price envelope” or revenue for a product or service.

• Costs can seldom be passed directly through to customers. Those costs that do not add value come out of profit.

• If across-the-board cost reductions are undertaken, then the value-added core is reduced and the price envelope collapses inward (less value is delivered so price decreases).

• Price is a multiplicative function of the value-added activities of the firm. This means that a dollar invested in value-added activities should deliver more than a one dollar increase in revenues as long as the firm is not overspending on a specific value attribute, given market conditions. Conversely, a dollar cut out of the value-added core will result in more than one dollar of revenue lost, creating a death spiral for the firm, under existing market conditions.

• Growth can only occur if the firm leverages its competencies in the areas that the firm’s customers value by reinvesting savings from cost reduction in business value-add activities and waste to activities and investments that support the value-added core.

These are the key assumptions that underlie the VCMS. Based upon this logic, the VCMS develops a strategic analysis of the preferences (value profiles) for various customers and customer segments. This information is then used to create an assessment of firm performance in general or for a specific product/service bundle. The customer is infused throughout this process, playing a central role in all decisions.

The Role of Customer Segments

Customer value analysis often leads to the identification of customer segments. For instance, Impact Communications,6 a public relations firm, was known in the marketplace for its “cause-based” market research. Research was the dominant focus of the owner of the firm and the research value attribute placed high on the list of attributes the firm offered to its customers.

As the firm grew, it acquired a broad range of customers with different needs. The firm, though, continued to place a heavy emphasis on providing research for its clients because it perceived that this was the area where it added the most value over its competitors. Problems began to occur as the firm started to have difficulty retaining new clients. Specifically, clients that wanted the firm to do basic public relations work (smile and dial) were dissatisfied with the service provided by the firm. Since this was the largest customer segment in terms of revenue, the problem received attention.

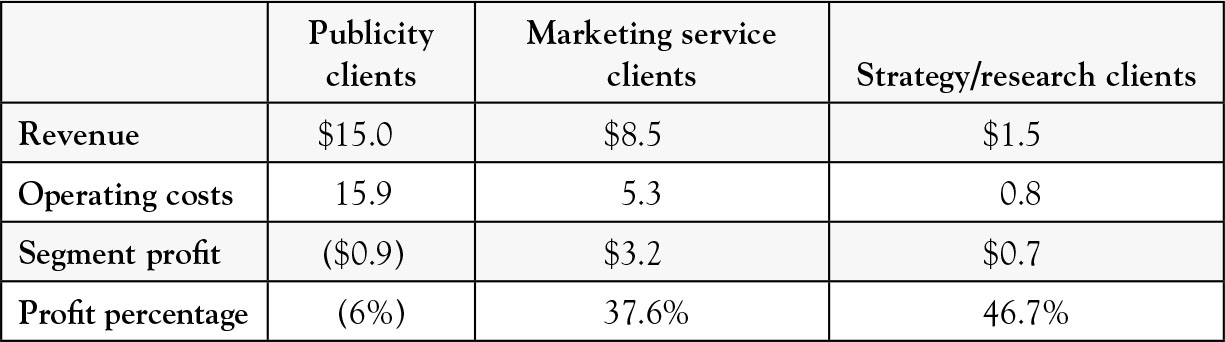

Of the existing $25 million in revenues, the customer base could be divided into the following segments (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3. Impact customer segment profitability (in millions).

As the figure suggests, not only was Impact having trouble retaining its publicity clients, it was losing money on this segment because all of the money invested to gain new clients was having to be absorbed by one, rather than multiple, engagements.

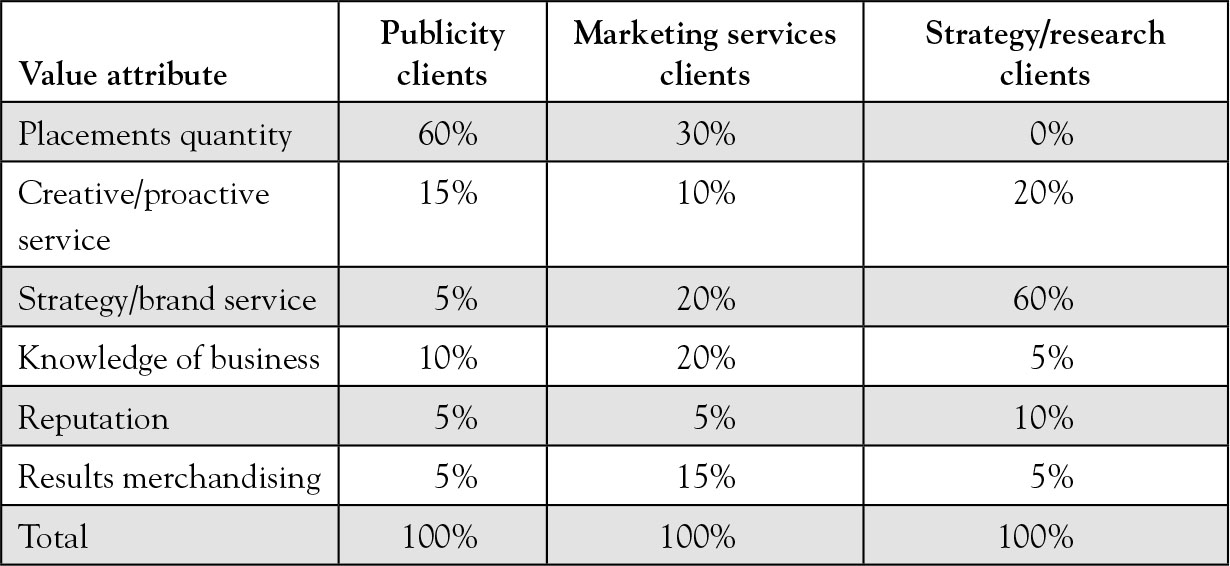

To better understand the problem, the decision was made to explore the value attributes of the different segments. The results, which are noted in Figure 2.4, were striking. There were marked differences in what the customer segments valued. Publicity clients were mainly interested in placements quantity, or namely how many places their product or name showed up in such things as press clippings. Research clients did not care about placements—they were at the firm because of its research expertise. The company was providing a “one-size-fits-all” product for a differentiated market.

Figure 2.4. Impact customer value attributes by segment.

Impact, as one of the early clients in the series of projects underlying the development of the VCMS, went from these unique value profiles to breaking down their internal cost structure by what value attribute was served. No attempt was made to separate out value-added costs at this early stage of the research.

What was learned at Impact Communications? That a firm can be very good at its core competency and leave most of its customers dissatisfied. Since the firm did the same work for every client and considered the placements activity as being a low-skill, undesirable task, it was failing to meet the expectations of its major customer segment—publicity clients.

Finally, during the course of the discussions the concept of “results merchandising” arose, something no one had considered. This translated to how good the individual who hired the firm looked to his or her management based on the quality of Impact’s final presentation. It was a value attribute Impact had not been aware of, one that drove 15% of the value for its general marketing services clients, who were mostly other small businesses that couldn’t afford their own marketing team.

Because of this work, Impact reconfigured its internal work to match up what they were doing with the customer’s value profile. Specifically, they asked customers to provide a value attribute weighting at the beginning of an engagement. Management reports were then created for clients that showed the spending of engagement dollars mapped against the customer’s value preferences. The power of value attributes and knowing how to best serve customer segments are a vital message contained in the results at Impact Communications.

Summary

In this chapter we have examined the concepts of value-added activities and value attributes, emphasizing how important it is to drive these concepts from the outside-in. A VCMS starts and ends with customer-defined value. By a simple transformation of customer data, namely making value attribute weightings add up to 100%, the VCMS merges accounting logic with marketing and strategy approaches to create an effective communication- and action-driving tool for management.

As we have seen so far, then, there are a number of criteria that are essential for any cost management system that seeks to support improvement in the amount and quality of a firm’s value-added core. Included among these are the following:

• Externally focused: The information required to create and support the cycle of growth in a company is not found in the general ledger. It resides in the external market, in the minds and actions of the firm’s customers. An effective VCMS has to focus on external, not internal trends and information.

• Growth-oriented: The cycle of growth is an investment strategy that emphasizes the rewards earned by improving the firm’s alignment with customer preferences.

• Future-oriented: Growth requires an orientation toward the future—one that places the emphasis on ensuring that the firm is constantly adjusting its activities to meet emerging customer requirements. Scorekeeping and reporting prior results are of much less use in a growth-oriented, value-optimizing firm.

• Profit-shaping: While all accounting is designed to capture and report profits, a VCMS is single-mindedly dedicated to supporting profitable growth through improved alignment of a firm’s activities and outcomes with customer preferences. A VCMS proactively shapes profits—it does not simply passively report them.

• Customer-driven: Customers, their preferences, and their satisfaction with current performance are all key constructs in a VCMS. Cost information and analysis is aligned with market-based information that highlights customer requirements.

• Dynamic: The demands of the customer are constantly changing, as new features, products, and needs emerge. The customer data supporting a customer-driven strategy must also be fluid, modified as conditions change.

• Value-based: The activities that take place in the firm have to be analyzed to separate out their value-added component from business value-add and waste. All activities have some component of business value-add and waste, even those that are mostly value creating. Gaining this detailed knowledge at the activity level helps the VCMS support all forms of process and lean management.

• Elegant: The methods for data collections and analysis must be elegant in a VCMS. The need to stay close to the customer, to constantly assess firm efforts against customer requirements, and to support adjustments and action to improve customer-defined strategic alignment requires an information system that can be easily updated, used, and adjusted to meet changing conditions.

These criteria suggest a very different form of cost management, one that is used to shape strategy, not evaluate the outcomes ex post. The result is a proactive, externally focused, customer-driven role for cost information and cost management practice.

All change is not growth; all movement is not forward.

Ellen Glasgow7