NINE

Avoiding the All-or-Nothing Trap

I grew up in a rural community. My father was completely blind. I am the oldest of four sons, and as long as I can remember I have had entrepreneurial desires. Despite some lofty ambitions, I was never any kind of a stand-out kid. I was one of those boys who was often overlooked, and I spent a lot of time hoping I wasn’t the last kid picked on the basketball team. Nonetheless, I had this incredible and deep desire to do something of significance with my life.

I remember when I was 18 years old and just finishing up high school; I wrote down some personal goals. I had always been goal-oriented, and my mother encouraged me to write down my goals. One of those goals was to become the CEO of a major company. Even though I wrote it down, I knew it was as far off of a goal as I could have set. I didn’t think there was any chance in the world of actually ever reaching that goal; in fact, I might as well have written that I was going to sprout wings and flap my way to the moon. And yet that became a powerful goal. It was my beacon in the fog.

I was very fortunate to have been able to get a good education. After graduating, I worked hard and had some incredible opportunities. And I ended up having the opportunity to work as a CEO and a general manager at some large and well-known companies. Midway through my career in corporate America, I was given a leadership role in a large, international organization. I was eager and determined to earn my stripes, and I basically committed to do so at all costs. I was a very young general manager of the U.S. division, and I was determined to do anything that was necessary to succeed. My commitment bordered on insane. I had a young family, but I was traveling hundreds of thousands of miles every year. There were nights I would stay at the office all night long to do what I felt needed to be done. I was going to succeed, and I didn’t care about the costs.

Then I learned the lesson that it is not worth risking everything of importance in your life to achieve success.

The division I headed became very successful. In the middle of our run, my mentor and boss, Dr. Peter Horne, called my secretary and said, “I need to have a visit with Rich.” That meant jumping on a plane, flying to Atlanta, then from Atlanta to Amsterdam, and from Amsterdam across the channel to Birmingham, England. Door-to-door, this was a 22-hour trip.

When I arrived, Dr. Horne pulled me into his office and sat me down. He then said, “Rich, we’re really delighted with the progress you’ve made in the business. Things are coming along rather nicely.” And then he made this comment, which has stuck with me: “I want you to remember one thing, Rich. You can replace almost anything in this world. You can replace a car. You can replace a job. You can replace money. But you can’t replace your health, you can’t replace your trust relationships, and, most important, you can’t replace your family.” Then he shooed me out of his office, and I began the long journey home.

Those 20 hours, which I spent alone on a very crowded airplane, gave me plenty of time to think about what Dr. Horne had just said. Most of my thoughts centered on my wife and children. For years I had been telling my wife, “This next project is a big one for me. I am going to give it my all for six months, so don’t plan on seeing much of me. But once I finish it, things will be different.” The six months would pass. I would complete the project, and then a new project would come along and I would start the cycle all over again. Those six months had turned into years as I kept promising, “If I give my all to this for six months, then we will have it made.”

As I flew back across the Alantic, I reflected on a trip I had taken to India some months before. When I got home, all of my sons and I came down with whooping cough, or pertussis. We had all been immunized, but somehow we contracted this miserable illness. It was terrible. I remember coughing so hard that I would frequently vomit, but I lacked the discipline to take time off from my work to get better and help my wife with our sons. My youngest son at the time was Nathan. He was less than a year old when we all got sick, and it was life-threatening for him. In fact, he ended up in the hospital, where my wife took care of him because I was too busy.

Flying home, I realized I was falling into the “all-or-nothing trap,” and I resolved that I was going to do better as a father and husband. The first thing I did when I got home was to gather my young sons together, give them each a hug, and tell them I love them. But when I went to pick up Nathan, he hollered and screamed. As he pushed me away, I realized he did not even know who I was. At that moment, I realized that achieving my goal of being a CEO was not worth losing the love of my family. And I began to change both my priorities and how I actually lived my life.

Now, that doesn’t mean I lost my intensity. It doesn’t mean that I never end up out of balance. But my short session with Dr. Horne brought great clarity to the fact that it’s not worth giving up the things that matter most for the things that matter least. This insight was part of what helped me see the Zigzag Principle as a far better way to approach life. Now, as I zig and zag from goal to goal, I will still put intense effort into achieving my dreams. But at each turn, I’ve established a reward that for me inevitably includes my family (your rewards, of course, may differ). And for each goal I pursue, I set up guardrails that will determine the amount of time and effort I am willing to invest. There are not many ways to succeed without going out of balance for a period of time. The key is to realize that you are going out of balance for a short period and then bounce back and take some time off to enjoy your life.

My philosophy involves a line of balance. Many people think you achieve balance by being at work exactly at 8 a.m. and leaving within minutes of 5 p.m., by getting eight hours of sleep each night, and by controlling life with a rigid schedule. I don’t live my life that way. At times I live my life extremely out of balance. I’ll work so crazy hard that I think I’m going to die, and then I’ll cross over and go for a cruise where I sleep 18 hours a day. Then I’ll charge back across the line and spend some incredible family time, then I’ll go work my guts out again and not sleep for a couple or three weeks while I start another new business. Then I’ll spend a month in the Himalayas with my family. The way I define balance is not to try walking the perfect line, but to cross that line of balance as frequently as possible. This is the final form of zigzagging I would suggest.

Added to my own bad example of having spent my early years charging straight toward my goals is the example of an individual who completed his MBA program the same time I did. He was a charismatic and brilliant man. He had everything going for him—far more than the rest of us did, really. During school and after we graduated, he was fixated on the same path I was on. He was going to the top, and he was going to succeed at all costs. I guess the only real difference between us is that I am fortunate enough to have a wife who has helped me become grounded and remember what really matters in my life. (Sometimes she has had to beat me over the head to make her point, but I count that as a form of help.)

This man was relentless in his pursuit of wealth. He racked up frequent-flier miles and spent even more time away from his family than I did. He did whatever it took to get to the top, and he got there. In fact, by traditional measures, he has achieved a level of success I might have been envious of at one point in my life. But now, as I look back over my life and this man’s life, I see some significant differences. He has been married and divorced multiple times. He has had more flings than I can count with my hands and my toes. He has no relationship with his children; in fact, they will not even talk to him.

I look at him, and I am so grateful that Dr. Horne took the time to counsel with me—and then put me on a transatlantic flight to think about what he said. As a result, my son Nathan, who would not let me touch him because he did not know who I was, now calls me his hero. Success is not worth heading over a cliff or getting so out of balance that we lose control. Everything in life requires balance. The best skiers cross that line of balance as often as possible as they race down the hill. But they know how to keep their momentum and stay upright through the race, rather than crashing and burning.

A key to maintaining our balance in life and in business is not getting so tightly wound up and so intense that we do not get in a rhythm, or what the best athletes call “flow.” In his book, Golf Is Not a Game of Perfect, sports psychologist Bob Rotella, who has worked with many of the world’s greatest golfers, talks about the mind-set that the best golfers have to get into. When golfers are playing at their peak, Rotella says, they are only using a part of their brain while the other part is shut down. It is almost as if they are in a trance. Things just come naturally to them. They are relaxed, and they let the intuitive and creative part of their brain do the work. That is flow.

Many of us, on the other hand, get so stressed and uptight that we create our own failures. Our stress then creates a form of reverse psychology, similar to what happens when I’m golfing and see a water hazard off to the left. If I allow myself to think (which Rotella would suggest I not do!), I tell myself, “Don’t go left into the water.” And, just like that, the ball invariably ends up going dead left into the pond. The same thing is true as we pursue our beacons in the fog. If we get fixated on the things we think we can’t do or if we get consumed with the possibility of a little error or failure, we get wound up too tight. And that actually translates into negative behaviors that undercut our efforts.

I experienced this phenomenon recently in our business with a client who is one of our biggest and longest-standing customers. Where he was once a pleasure to work with, he had become more difficult, demanding, and disrespectful. He felt our terms and conditions didn’t apply to him. Because we felt such a need to hang on to him, we would make accommodations, which led us to breaking our own rules, abandoning our processes, and crashing through our guardrails. In short, we didn’t want to lose him, and we held on too tightly.

Finally, Curtis and I got pushed to the point where we realized we had wasted far too much energy on this client—and that we were holding on too tight. So, we began to let go a little bit. We knew we might lose his business, but we decided that was better than the alternative. Rather than chasing after him in a desperate mind-set, we adopted a “take it or leave it” attitude, believing that if things didn’t work out with this customer, we would find another one. And that keeps us out of the “all-or-nothing” trap.

In the end, the Zigzag Principle will help us avoid the “all-or-nothing trap” as we work our way toward our beacons in the fog, whereas a straight line will lead us straight into the weeds. I once listened to Jeff Sandefer, a university professor and Harvard MBA who Bloomberg Businessweek named one of the top entrepreneurship professors in the United States. Jeff spoke of a final exam he gave his MBA students, who were required to speak with 10 seasoned and successful executives. Jeff further specified that the first three executives they interviewed needed to be highly successful, but under the age of 35. The next three successful executives were to be in their mid-forties and fifties. The final four interviews were to be with successful executives who were in the final stages of their careers. In each of the interviews, Jeff’s students were to elicit information on how these executives pursued and viewed success.

Invariably, the young bucks were beating their chests and chasing after the brass ring, often in ways that put them at risk of losing their balance. The middle-aged executives were beginning to figure life out. Some of them had regrets and others had chosen to add some balance to their lives.

Of course, it was the older executives who gave the real insight. It did not matter what type of business these men or women were involved with. In each case, they described a pattern of pursuing success that was guided by these three questions:

1. Was it honorable?

2. Did it leave an impact?

3. Who loves me and who do I love?

Many of these older executives were billionaires. And yet they talked very little about money. What mattered to them was how their business helped others and whether their business mattered. They wanted to leave a legacy. And most important, they talked about the people who loved them and the people they loved. Of course, there were those who did not have loved ones, and they talked about that absence with regret. They were honest and open and direct about their successes and their mistakes.

Whatever our goals are, whatever our beacon in the fog is, it is critical that we do what we do for the proper reasons and that we stay within the guardrails and values that we have set for ourselves. If we do, we will get to the end of our lives—a day which will inevitably come—and have no regrets.

The Zigzag Principle is a disciplined approach to business and life. It is not an “easy” approach; in fact, it requires incredible effort to traverse the mountain before you as you make your way to your destination. But being willing to zigzag—and then doing it with control—will help you build a business and a life that will be stable and strong.

As we wrap up this journey we’ve taken together, I want to reiterate the underpinnings of the Zigzag Principle:

You must begin by creating a foundation.

![]() First, you need to look deep into you pockets and see what resources you have right now.

First, you need to look deep into you pockets and see what resources you have right now.

![]() Second, you must determine what your beacon in the fog is going to be.

Second, you must determine what your beacon in the fog is going to be.

![]() Third, you must identify and hold to the values you are going to follow in pursuit of that particular goal.

Third, you must identify and hold to the values you are going to follow in pursuit of that particular goal.

![]() And, finally, you must fuel your efforts with passion and determination.

And, finally, you must fuel your efforts with passion and determination.

Once your foundation is set, you can begin to zig and zag toward your goal.

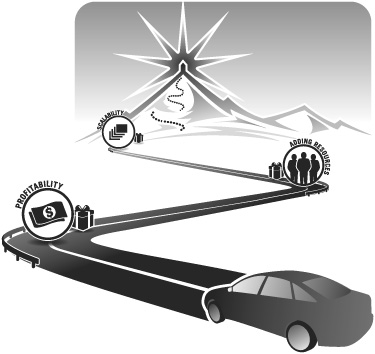

![]() The first zig is always to get to profitability. If you do not meet this goal, then you must try something different and keep trying until you get your business or your life profitable.

The first zig is always to get to profitability. If you do not meet this goal, then you must try something different and keep trying until you get your business or your life profitable.

![]() The second zag is to use the cash from the previous zig to add resources. This requires you to let go just a bit and teach other people how to travel with you in pursuit of your dream.

The second zag is to use the cash from the previous zig to add resources. This requires you to let go just a bit and teach other people how to travel with you in pursuit of your dream.

![]() The third zig is to scale your business. This is the part when you are working on your business, not in your business.

The third zig is to scale your business. This is the part when you are working on your business, not in your business.

There will be more zigs and zags as you work toward your final beacon in the fog.

![]() Look forward and plan three zigs ahead. The third zig out can be adjusted and changed to match the terrain of the trail you are following.

Look forward and plan three zigs ahead. The third zig out can be adjusted and changed to match the terrain of the trail you are following.

![]() Your zigs and zags need to be bound by guardrails. These guardrails are the things that will keep you away from the trees, the weeds, and the cliffs. They are always aligned with your values.

Your zigs and zags need to be bound by guardrails. These guardrails are the things that will keep you away from the trees, the weeds, and the cliffs. They are always aligned with your values.

![]() Each zig and zag is bound by how much money, time, and personal resources you have predetermined to put toward your goal.

Each zig and zag is bound by how much money, time, and personal resources you have predetermined to put toward your goal.

![]() In each case, there is a financial target you need to achieve before you can turn toward the next zig, and this target is always bound by your knowing what you can and can’t afford to lose.

In each case, there is a financial target you need to achieve before you can turn toward the next zig, and this target is always bound by your knowing what you can and can’t afford to lose.

As you hit each zig, there will be a planned reward.

![]() The rewards are the motivation that will make you and those around you choose to make that turn toward your next zag.

The rewards are the motivation that will make you and those around you choose to make that turn toward your next zag.

I set some very ambitious goals for myself when I was a rather ordinary young man living in rural Utah. At the time, I was determined to achieve success in life, and I considered a straight line to be the path to follow in achieving those goals. When I mowed lawns to save for college, I loved to finish a job and look back at those straight lines I had created. If there was a door in my way, I didn’t see any need to open it to get to the other side. If there was a cinderblock wall between me and my goal, I was generally smart enough to recognize my need to go around it, but not without considerable resentment and a consideration of the odds of my crashing straight through.

Given all of the skiing and mountain climbing I’ve done, coupled with my wife’s insistence that we not chart our course to Disneyland as the crow flies, it’s curious to me that it took me as long as it did to realize that zigzagging really is both a law of nature and (with few exceptions) the most effective way of getting to where we’re headed. But I finally did come to that realization, and by adopting a philosophy that was once antithetical to my very nature, I have achieved considerably more success, even as I have maintained my sanity and my sense of balance and control over those things in my life that matter most.

While this book has, at times, focused on business settings and practices, the Zigzag Principle can be used in any part of your life. It changes the rules from “one strike and you’re out” or “it’s all or nothing” to principles that help you navigate toward your beacon in the fog.

You may miss the mark sometimes. That’s fine, as long as you take a minute to get your head above the fog and pinpoint once again where you’re headed. And as long as your zigs and zags are guided by your catalyzing statements.

There is nothing more satisfying to me than standing with a son at the bottom of a ski slope and examining the tracks we’ve made in getting down a seemingly impossible slope. Or standing on a jagged mountain summit with my wife and children and retracing our steps to the top. Both are remarkable views—ones that I hope you too will enjoy.