Scan the Market, Manage the Risk

“It is remarkable how far some people will go to avoid thought.”

—THOMAS ALVA EDISON

Every endeavor, from sports to warfare to business operations, demands preparation if you expect to succeed. In a business enterprise, or even a not-for-profit organization, preparation starts with an environmental scan. An environmental scan studies all forces external to an organization that are relevant to its operation. HCM:21 also looks internally at situations that may need reconfiguring in the new term. The key question a scan answers is: What is going on outside and inside that might affect future operations?

There are scans and there are scans. Many scans are little peeks into the future as a preparation for budgeting. Often, there is no intent to change anything. The scan is seen as a perfunctory act, which must be done to satisfy someone. Of course, someone looks at the market, but how broadly or deeply does the person study it? A true scan, however, is both wide and deep. It is not confined to one aspect of the external environment, such as labor demographics or economic trends. The intent is to find something useful, not just collect information that confirms current or past beliefs. True scans cover every potentially relevant variable outside the organization, as well as inside. In the process, this intent acknowledges that there are factors inside an organization that could benefit from an in-depth review, and these include, but are not limited to, the CEO’s vision, brand, culture, leadership, financial viability, and employee capabilities.

The other aspect of a true scan is that it looks for connections between and among the external and internal forces at work in the organization’s environment. This is where the “value door” opens. Because an organization is so complex, the variables constantly connect, collide, separate, and frustrate each other. They can both reinforce and create chaos. This interplay is often unrecognized because most organizations operate as a set of silos. Each function can become so myopic that it doesn’t see, know, or care about the others. Indeed, this is a perennial misalignment problem that many organizations struggle with, and it is a barrier to their sustainable success.

The Big Picture

Predictive management, or the essence of HCM:21, executes a strategic scan of the external forces and internal factors that can affect the three fundamentals of an organization: human, structural, and relational capital. Human capital is your employees. Structural capital is the things you own, ranging from patents and copyrights, to software programs and codified processes, to physical facilities and equipment. Relational capital is the knowledge and contacts you have with external stakeholders, which includes everyone who is touched by your organization—the list can be quite long.

Externally, the forces can include at least the following:

Industry trends

Competitors

Brand reputation

Technological advancements

Regulations and laws

Regional, national, and global economic situation

Globalization demands

Customer demands and interests

Supplier capacity

Materials quality, prices, and availability

Labor supply

Job applicants

Educational institutions

Stockholders

There are also internal matters that might affect the organization’s ability to manage effectively. The inside list includes factors that need to be reviewed in light of recent market trends. The list can include:

Vision

Values

Culture

Leadership

Management wisdom

Mission-critical retention rates

Engagement levels

Facilities and equipment

Product life cycles

Employee brand awareness

General turnover levels

Skills and capability levels

Financial capability

Ability to enter new markets

Quality, innovation, productivity, service (QIPS) levels

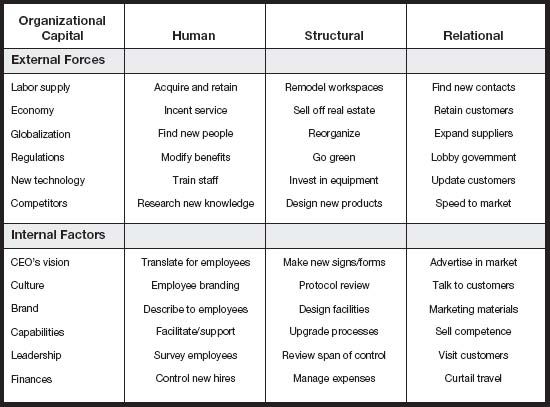

Figure 3.1 is an outline or template, in the form of a matrix, for a strategic scan of an organization’s environment. It is not all-inclusive; in practice, the list of forces and factors that management generates can be much larger. Still, this matrix shows the range of effects likely to be relevant to your organization. By using this matrix, you can see the connections and influences across various cells. Management acknowledges superficially that everything in an organization is tied together; however, the interrelationships are often downplayed. Focusing on these interdependencies is the first place where our model brings in the critical concept of integration.

Look at the template. Do you see how people and facilities interact? How obvious is it that technology affects both employees and customers? Only after you take this initial step can you begin to plan for the future. Otherwise, you are operating like Lewis and Clark, exploring an unknown territory. Every morning, you will wake up wondering what danger will be lurking over the next hill.

You might have noticed that, among the items listed as “internal factors,” is brand. Although brand is a separate factor, in actuality, a CEO’s vision, culture, and brand must overlap and function in a single, integrated manner. Obviously, a CEO’s vision drives the corporate culture; in turn, culture and brand correlate. If your brand stands for high quality, great service, or precision, then your culture must personify that. A loose culture cannot provide great service or high-quality products. Additionally, culture and brand are made visible in the way you design and maintain work spaces (structural capital). Product quality is certainly dependent on good tools, well-maintained facilities, and efficient processes.

Figure 3.1. Template for a strategic scan.

The more you examine the matrix, the more you will understand how interdependent everything is within an organization. Ironically, companies work against that concept as they set up separate silos for functions and reward departments for their performance—performance that may or may not support the overall effectiveness of the organization.

Disruptive Technologies Bring Change

Consider the health-care debate in America today. All parties, from providers to insurers to the government, have a stake in any changes to be made in our health-care delivery system, especially how to curb the steadily rising costs while expanding health care to all people. Providers want to do the best job they can, while limiting their liability for errors. Insurers want to provide coverage as long as they can raise premiums fast enough to maintain profits. Government’s goal is to expand coverage to the uninsured without raising taxes. In all the arguments, the basic point is not being addressed. How do we contain costs and still provide service when 70 percent of the money goes to pay health-care professionals? The answer is disruptive technology.

We have to think differently. The old model doesn’t work because it is inherently inefficient. Hospitals have always run on a cost-plus model. That is no longer feasible, for several well-known reasons. So, how do we disrupt the model? Disruption seldom comes from inside, where all the vested interests lie. It intrudes from outside, where fresh visions are born. In this case, we need a vision from outside of new ways to manage inside costs.

Think of the just-in-time (JIT) inventory control and process optimization that were adopted in the 1970s. America adopted the inventory-maintenance ideas from the Japanese system for reducing costs. And it is not only the material cost that is saved; in a JIT inventory system a company also doesn’t have to pay for a large warehouse. Inventory does not become obsolete as it sits waiting to be used; hence, waste is eliminated. Also, there doesn’t have to be a large staff to manage masses of material.

Applying the idea to health care, we find isolated cases in America where hospital managers use JIT and have cut some material costs by over 50 percent. Process optimization also has cut costs by reducing the time that health-care providers spend on administrative procedures. Streamlining the time it takes to get supplies and to discharge patients has helped hospitals shift nursing staff to providing care in lieu of filling out forms. Additionally, this shift in work cuts down on nursing errors, which often add to a patient’s time in the hospital. Open-minded, in-depth scanning can reveal relationships among forces and factors, and that marketplace data can be turned into management intelligence.

Another Case of Missed Opportunity

The value of scanning comes through in another example. In this one a major retailer had been gradually introducing nonperishable food items into its general operation. Although the food was processed and packaged, it required special handling that the retailer’s regular shoe boxes and sweaters didn’t. Yet, this situation was not immediately appreciated by management. But the scan revealed new problems involving structural capital. Now, warehouses had to be cleaner and more sensitive goods had to be handled differently. The scan showed management that heating and air-conditioning, plus refrigeration, were now mission-critical issues.

Additionally, the scan pointed out that within America’s vastly diverse populations, there were significant differences in food consumption. If the retail stores and warehouses were in Los Angeles or Miami, they needed to stock Mexican and Latin American foods—and this meant more than tortillas and jalapeños. Other cities had large Indian, Greek, and Middle Eastern populations to be considered. Before the scan, some stores in those ethnic enclaves lost sales and market share because they didn’t consider the needs and desires of their customers. For managers accustomed to offering clothing and furnishings, meeting this new need was a challenge.

This example is not offered here to suggest that the managers were stupid. What it showed was that people tend to rely on past experience and so they miss seeing opportunities. The past is not a precursor to the future anymore. When the philosopher George Santayana said that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” he meant the lessons learned from the past, not past methods per se.

The Value of Statistical Analysis

We work to develop algorithms with our clients so as to statistically analyze and weight the connections between their external forces and internal factors, as well as the issues that come later, such as process optimization, service delivery, and performance measurement. To reveal those connections, clients collect operating data and format it in a way that allows us to carry out the statistical analyses. This leads to predictability.

The value of analysis is in the patterns in data that it uncovers. These patterns are not readily apparent in standard reviews and reports. Hence, analytics is more about structure and logic than about statistical procedures. Statistics are useful only if they are applied to the right issues. Large organizations are so complex and their operations so far-flung that it is virtually impossible for management to see some of the vital connections and influences. But using computing power and analytic tools to mine the data can yield vast and varied phenomena. There is a natural reluctance among managers to accept that statistical methods are more accurate than their judgment. Yet, the experience of managers is contaminated by common human traits of bias, misperception, and faulty memory. In 136 studies of the judgment accuracy of experienced managers, only 8 studies showed that manager predictions were more accurate than simple regression equations applied to the same problems. In a post-study review, the analysts believed that random-sampling errors accounted for the mistakes in the predictive power of statistics and that actually regression beat manager memory every time.1

The Importance of Risk Assessment

Risk is a central element in any kind of planning. A statement about the future carries with it the risk of being somewhat to totally wrong. Even grand financial models miss some aspect, which can lead to disastrous investments. Today, there are many more external forces driving companies now than in the past, and that involves recognizing risk. Stability is gone for good; it has been replaced by volatility, extending far into the future. And, unquestionably, human capital management is a high-risk game in this uncertain market. More than ever, human capital planning must now include risk assessment.

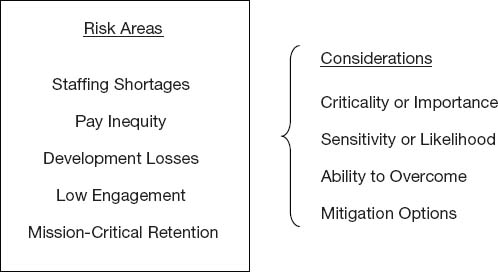

Risk assessment has three steps. First, the scan lists every factor that can potentially have an impact on the organization. For human capital management, those factors are edited to those that could have the biggest negative or positive effect on the organization’s people, operations, structure, and external relations in the foreseeable future. Then, the question is asked: What will be the impact if these occur? See Figure 3.2 for a sample.

At the corporate level, examples of potential risks could be immediate loss of revenue, inability to deliver competitively, harm to the organization’s reputation, legal penalties, and loss of future revenue. On the positive side, if a new product release exceeds expectations, great—but will the company be prepared to service that increased level of uptake?

Figure 3.2. Sample HR risk assessment.

Second, each risk is rated on a scale of, say, 1 to 3 with regard to its likelihood of occurring. How do you decide the likelihood something is going to happen? You have to look beyond the experience of people in the organization and research current media reports. That is where the threat lies—so listen to the maniac fringe. Visionaries and others operating at the outskirts often see ahead more clearly than do those in the establishment, who have something to protect.

Remember, almost every disruptive change has come from outside the current leaders in a business or industry. Consider the personal computer, the mini steel mill, the digital watch, Internet book sales, and overnight package delivery. Each idea came from an outsider. Managers have some control over internal factors but they have little or no control over those outside the organization. If one of these threats or opportunities materializes, what might be the extent of the disruption? How long will it take the organization to respond? And do you have the ability to implement effective risk-mitigation measures?

The third step involves applying the optional responses. From importance and likelihood, you decide how to mitigate the effects of those risks. For example, how will you handle the following?

![]() Avoid the risk by postponing or not implementing something—or just wait?

Avoid the risk by postponing or not implementing something—or just wait?

![]() Transfer the risk to a third party—in which case, who could do it better?

Transfer the risk to a third party—in which case, who could do it better?

![]() Reduce risk by introducing controls, but how and what controls? Accept the risk if the cost outweighs the benefit—but how to balance the situation?

Reduce risk by introducing controls, but how and what controls? Accept the risk if the cost outweighs the benefit—but how to balance the situation?

![]() Capitalize on an unexpected positive result—or how best to stay agile?

Capitalize on an unexpected positive result—or how best to stay agile?

Your task is to develop a risk-mitigation plan that prepares you ahead of any problem’s arrival. It is similar to a disaster-recovery plan. That is, if the worst happens, you are ready to clean up in the most expeditious manner. This approach reduces damage and confusion, and helps you move on with a minimum of distraction. In short, while the unprepared flail about in the bushes, trying to get back on the trail, you distance yourself from the pack.

One of the most effective ways to prepare for the unexpected is to develop a playbook, much as is done in the game of football. The play-book lists the defensive and offensive plays that are ready to be used, given certain circumstances. Jim Ware’s essay “Scenario Planning,” in Chapter Four, describes how to use a playbook.

The Data Speak for Predictive Management

In 2007, The Hackett Group published the results of its research on the effects of managing human assets. It studied 125 human resources/ human capital benchmarks over a three-year period. The metrics were chosen to reflect a balance between talent management and corporate efficiency and effectiveness, and the purpose was to zero in on the effect of human capital planning and management on productivity, customer satisfaction, and employee commitment, and by extension, on sales, profits, and shareholder value.2

Hackett’s research found a strong correlation between improved financial performance and top-quartile performance in four key talent-management areas:

1.Strategic workforce planning, which involves identifying the skills critical to a company’s operation and how these needs match up against those of the existing workforce

2.Staffing services, including recruitment, staffing, and exit management; and workforce development services such as training and career planning

3.Overall organizational effectiveness, including labor and employee relations, and performance management

4.Organizational design and measurement

Companies with top-quartile talent management, which includes planning, outperformed typical companies across four standard financial metrics. They generated EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) of 16.2 percent versus 14.1 percent for typical companies. This gap netted a typical Fortune 500 company (based on $19 billion revenue) an additional $399 million annually in improved EBITDA. How much more do you have to sell to net $400 million?

The most interesting point in the findings correlated with another study, which reported that top talent-management performers operate very differently from their peers.3 According to the report, top performers are 57 percent more likely than their peers to have a formal HR strategic plan in place, more than twice as likely to facilitate strategic workforce planning discussions with senior management, and 50 percent more likely to link their learning and development strategy to their company’s strategic plan.

Ready, Aim, Begin

The environmental scan of external forces and internal factors discussed in this chapter produces a picture of what is likely to happen, what you have to compete with, and how these things will affect your human, structural, and relational capital. Risk assessment prepares you for possible major problems and rates the types of risks you might expect. It gives you a framework for identifying and mitigating that risk. From this you have a foundation for an advanced capability and succession-planning program.

Now, you are enabled to make plans to build management and leadership capabilities across mission-critical functions. Rather than continuing to apply an industrial model of filling holes with interchangeable bodies (gap analysis), you think in terms of building capability for the intelligence age. These are the issues in this chapter.

Notes

1.Ian Ayres, Super Crunchers (New York: Bantam Dell), 120–21.

2.“Companies Can Improve Earnings Nearly 15% by Improving Talent Management Function,” The Hackett Group Research Alert, 2007.

3.Workforce Intelligence Report, Human Capital Source, 2008.

HOW TO IMPROVE HR PROCESSES

The essays that follow discuss issues of how people and profits fit together, how a new view of compensation can be used as a total-rewards process, and what the best-practices companies do to earn that title.

THE INTERSECTION OF PEOPLE AND PROFITS: THE EMPLOYEE VALUE PROPOSITION

Joni Thomas Doolin, Michael Harms, and Shyam Patel

Any study of human capital management is ultimately about one thing: eliciting results. It’s an age-old question—How do you turn a disparate group of individuals into a high-performing team that drives the bottom line? People Report has spent over a decade exploring the connection between people and profits. What we have found is that, now more than ever, people matter.

Human capital is the defining component of any successful business. Between every great business plan and every consumer exist the people who will implement the steps necessary to ensure the plan’s ultimate success or failure. It is at this pivot point that hard and soft sciences collide, and for this very reason, human capital remains enigmatic to many in the business world. It is the human element that makes it so explicitly fascinating—and unpredictable.

While the variability of human behavior can be a source of frustration, any predictability you can garner becomes a key competitive advantage. This is where metrics and the use of measured human capital intelligence become mission critical. People Report is highly regarded as the foremost provider of human capital and business intelligence for the foodservice industry, the largest employer in the United States other than the government. While measuring the people practices of an organization is not always easy, measuring the results is. What we have found is that highly engaged, motivated teams outperform their peers, time and time again. The first step is hiring the right people; the second step is keeping them. As we have known for years in the marketing department, the key to attracting and keeping new consumers is in understanding your value proposition. We have likewise identified and defined the key inside the organization: knowing your company’s employee value proposition.

Exploring the Employee Value Proposition

It is crystal clear to most operators that recruiting and retaining quality employees is as difficult as ever. As one industry CEO recently lamented, “Everything works about half as well as it used to.” But before we simply concede defeat and accept the fact that shifting labor market conditions have made recruitment and retention perilous, consider this: The U.S. Army and Marine Corps continually meet and exceed their recruitment and retention goals. And this comes in the midst of a two-pronged offensive in the Middle East with the prospect of extended tours and mortal danger for new enlistees. This is a clear demonstration of what can be done.

So how does the armed forces do it? It started by adjusting the value propositions it offered new enlistees, from offering sign-on bonuses to changing its internal culture to a kinder, gentler army. We understand the importance of creating a value proposition for our guests—one that will get them to come to you again and again, talk about you to their friends, and use you for different meals and occasions. It’s all about building raving fans. But how many of us think the same way about our employees? What about their value proposition? If we want to attract “raving” employees, how do you do it? How do you convince people they can’t miss the opportunity of working for your company?

What Is Your Employee Value Proposition?

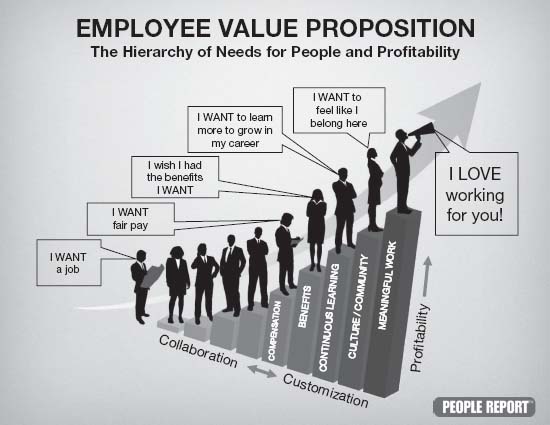

As employee needs and values have transformed and the workforce has diversified, we have started to think about the employee value proposition as the connection between people and profitability: The critical link between employee and guest is the key to organizational performance. Although a lot of lip service is paid to the idea that people are an organization’s greatest asset, they often are treated as disposable assets.

American psychologist Abraham Maslow developed the idea that certain basic needs must be met in each of our lives, and once these needs have been met, it frees us to increase our engagement and continue our development. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs has five levels:

1.Self-actualization: personal growth and fulfillment

2.Self-esteem: achievement, status, responsibility, reputation

3.Belonging and love: family affection, work group

4.Safety: protection, security, order, law, stability

5.Survival: basic life needs—food, shelter, sleep

For most people, work plays a huge role in their lives, and just as individuals have needs, so too employees have needs. While many employers take every available step to separate their employees’ work lives from their “real” lives, making work life more like real life will help attract and retain a talented workforce. This starts with meeting the basic needs of your employees by providing them with necessary compensation and benefits, as well as an environment designed for professional growth. If employers can satisfy the basic needs of their workers, the result will be an engaged group of employees who drive profitability, as Figure 3.3 shows.

If a company wants to succeed—today and in the future—it must attract and retain great employees. As most business gurus contend, “In the long run the most profitable companies are those that take care of their people… . Without qualified people who are happy and productive, the company’s long-term prospects are mediocre at best.”1

Engines of Revenue Growth

The impact of good people on an organization cannot be underestimated. While many in the business community would likely categorize employees as “necessary expenses,” they should be more willing to think of their employees as “engines of revenue growth.” This language may resonate already with chief people officers and human resources departments, but it should sound the loudest in boardrooms and financial departments across the industry.

Figure 3.3. The employee value proposition.

When we look at the financial performance of those companies that have won People Report Best Practices Awards—that is, companies with recruitment and retention numbers that are best in class—the results are astounding. Those companies whose people practices exceed those of their peers’ exhibit markedly stronger total restaurant sales growth and comparable restaurant sales growth.2

Compensation

The concept of a people-driven enterprise means that you must make a strong case for actively recruiting and retaining your best employees. The question is: How do we accomplish this? If we return to the needs hierarchy shown in Figure 3.3, we find it no surprise that the most basic employee need to be satisfied is an individual’s compensation and benefits. Typically, the obvious tool for organizations to meet those needs is periodic compensation increases. However, even in the current recessionary period, a paycheck is easily replicated by competitors; remember—”If people come for money, they will leave for money.”3

That is not to say that a competitive compensation offering is unimportant. But when we look more closely at the compensation practices of the foodservice industry compared to other industries, we find that average starting salaries are exactly that: average. The industry responded by adding bonus and incentive programs, under the assumption that it would attract productive employees who would be paid to perform.

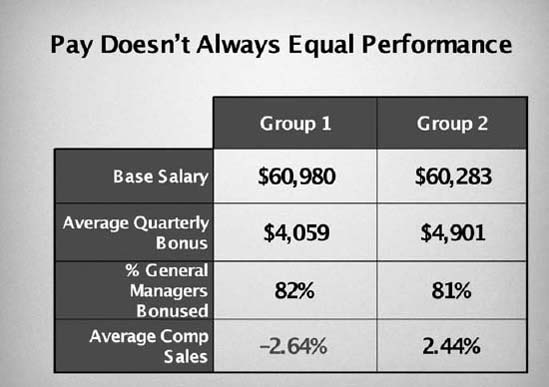

Unfortunately, foodservice industry bonuses have become more of an entitlement than an incentive, and the industry is learning a lesson that professional baseball’s New York Yankees picked up during the past decade: high compensation does not guarantee high performance. In fact, when reviewing the relationship between comparable restaurant sales and general manager bonuses as a percentage of base salary, we see as many companies paying an identical bonus as a percentage of base salary for negative comparable sales results as positive results (see Figure 3.4). Note that the compensation packages offered to Group 1 and Group 2 are strikingly similar, even though their performances are not.

This is not a critique of the industry’s variable pay plans; we understand the complexity of incentivizing thousands of operating managers. Rather, it illustrates how difficult it is to differentiate yourself from your competitors using these practices. That is, underperforming companies are paying as well as high-performing companies.

Figure 3.4. Comparative results of base salary and sales.

Source: People Report, Casual Dining, January–June 2007.

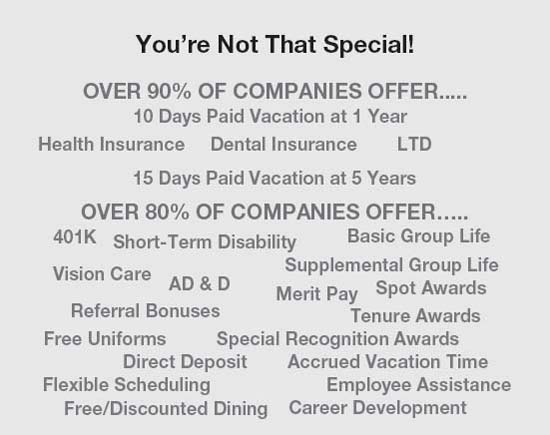

Similarly, it is difficult to stand out from the crowd because of the standard benefits packages your company might offer. Benefits matter— they are often very important to employees—but 85 to 90 percent of our People Report consortium members offer the same benefits; see Figure 3.5 on page 62. They do not differentiate you from your nearest competitor, and your employees have no incentive to stay longer because their next employer is offering basically the same package.

Benefits have become to employees what shelves at the market have become to consumers—a commodity that you must offer but that is less frequently a reason to come or to buy. That said, while a quality, standard benefits package has become commonplace in the industry, companies have been able to differentiate themselves by customizing their packages to best meet individual needs of employees. People want to feel as if they are taken care of and appreciated as individuals. Simply offering a more flexible package can make or break a decision to stay. So, if you have determined that compensation and benefits are not necessarily creating an incentive for your employees to stay with you, where do you look next?

Figure 3.5. Comparative benefits packages in the foodservice industry.

Source: People Report, 2009.

A Paycheck and More

We find it everywhere else in the workplace. As best-selling author and business consultant Chester Elton notes, “While a paycheck gets them to show up every day, it doesn’t buy long-term engagement.”4 As a look at the needs hierarchy shows, people do not want just a paycheck—they want a paycheck and more.

Part of the “more” most employees want can be seen in the higher steps up the hierarchy. They want to grow in their role and have a chance to move up within the organization, and they want to feel that they are appreciated and that they belong. Developing this sense of community and a culture of continuous learning starts with finding the right people.

Nearly all restaurants struggle to find and retain hourly employees. But data reveal that much of the industry’s recruitment efforts seem based on a strategy of hope, as in you hope someone walks in the door, an employee refers a friend, or a candidate reads an advertisement in the paper. Even in this extremely upside-down employment market, there are still open jobs, and the rate of employee turnover means that the search for enough of the “right” workers continues.

Many proactive operators have turned to data mining, as “data mining shows that these personality traits are better predictors of worker productivity (especially turnover) than more traditional ability testing.”5 Data mining and predictive analytics help match employees who are most compatible with particular jobs. Talent assessment and screening firms specialize in helping match applicants to job requirements, assisting companies in streamlining the process. They help find the best fit that leads to hiring employees with a much longer tenure. And while technology is a great way to improve the odds of recruiting and hiring good employees, the operators must also turn to new, diverse pools to find the top talent. Years of research have validated the advantages of both data mining and hiring and retaining a diverse workforce. Both lead to improved retention of managers and employees.

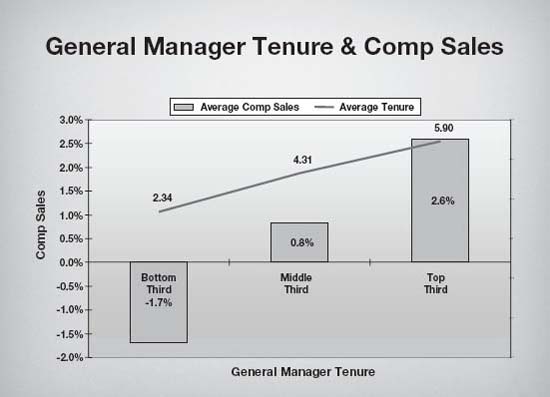

Retention Drives Sales

Retaining quality employees really is like finding that bottle of fine wine that improves with age and increases in value over time. This is especially true in the case of selecting general managers. In reviewing our data, we found that companies that reported the lowest comparable (comp) unit sales also employed general managers with the shortest average tenure. Not surprisingly, those companies whose comparable sales were the highest had hired general managers with the longest average tenure. In short, retention pays off, as shown in Figure 3.6.

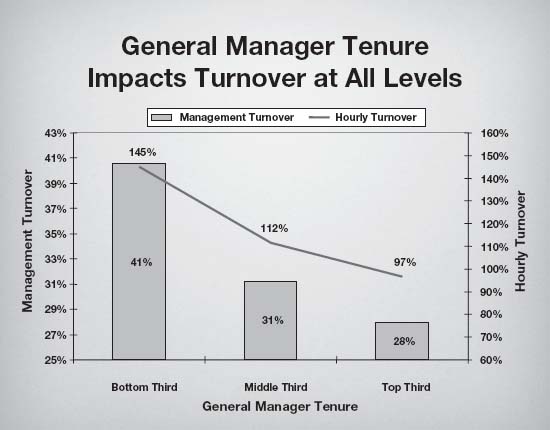

If increased sales are not enough to get your attention, here’s something else that will win you over. The tenure of general managers impacts the retention of managers and employees as well. As the length of employment for general managers increases, line-level management and hourly employee turnover plummets. Among People Report member companies, those that rank in the top third for management tenure—whose managers stay the longest—have almost 20 percent less management and 50 percent lower hourly turnover numbers. This calculates to a massive savings in comparison to the direct competition. Not only do companies with longer tenured general managers see increased comp sales, but they also see significantly reduced rates of management and hourly turnover, as shown in Figure 3.7.

What does all this equate to in dollars? Based on the overall cost of turnover, for every point a 100-unit company saves in hourly turnover, it recoups $205,000 annually in costs. Likewise, for every point saved in management turnover, it recoups $140,000 in annual costs.6

Figure 3.6. Comparative tenure results for general managers.

Source: People Report, 2009.

Now, translate that into what could happen for you. What if your initiative helped you reduce your organization’s hourly turnover by 10 percent and management turnover by 3 percent? That would result in an estimated cost savings in excess of $2.5 million annually for a company with 100 units. We have consistently been able to validate the value of recruiting and retaining quality employees. This is a winning investment; or, authors Bill Catlette and Richard Hadden note in their book Contented Cows Give Better Milk, “In the final analysis, ‘people factors’ are frequently the key source of competitive advantage—the factor least visible to the naked eye and most difficult to emulate. Sooner or later, we must come to grips with the fact that most businesses aren’t so much capital-or expertise- or even product-driven as they are PEOPLE-driven.”7

A Place They Belong

Creating a workforce where people feel included is important, for this reason: People don’t work where they have to; they work where they want to. Even in this economy, the best people will not stay forever where they are not appreciated. Turnover is frequently driven by emotion; feeling overlooked, underutilized, and unappreciated leads people to move on. Chester Elton has dubbed this workplace phenomenon “presenteeism.” While job abandonment continues to plague our industry, how many of us also battle presenteeism? As Elton points out, “Absenteeism is easy to spot, but presenteeism describes workers who show up every day, but aren’t really there.”8

Figure 3.7. Impact of general manager tenure.

Source: People Report, 2009.

Indeed, there’s an undoubtedly human element in retention and performance in all industries, particularly those as labor-intensive as foodser-vice. “Human beings are uniquely capable of regulating their involvement in and commitment to a given task or endeavor… . The extent to which we do or do not fully contribute is governed more by attitude than by necessity, fear, or economic influence.”9 Much of this attitude stems from the culture of the work environment. Do employees feel like members of the work community? Do they feel as if they have a chance to increase their role in the organization or do they simply feel viewed as “replaceable cogs in a machine?”10 One thing is certain: When the work environment begins to sour, the best employees are often the first ones out the door because they have the most options.

One Size No Longer Fits All

Customized experiences are an increasingly popular concept in all aspects of life. Not that long ago, three television networks dominated the national landscape, commanding huge audiences on a nightly basis. Now, they are awash in competition. The same goes for most large daily newspapers, which have seen declining circulation and advertising revenue for years as new, more targeted mediums have become prevalent. We are rapidly progressing toward a “what-we-want-when-we-want-it” society—the music you want at the click of a button, on-demand television, self-designed clothing. You can even customize your M&Ms. Who was Time magazine’s person of the year in 2007? You. It’s a customized world. People are not only comfortable with this level of customization in their lives, they expect it. Why should work be any different?

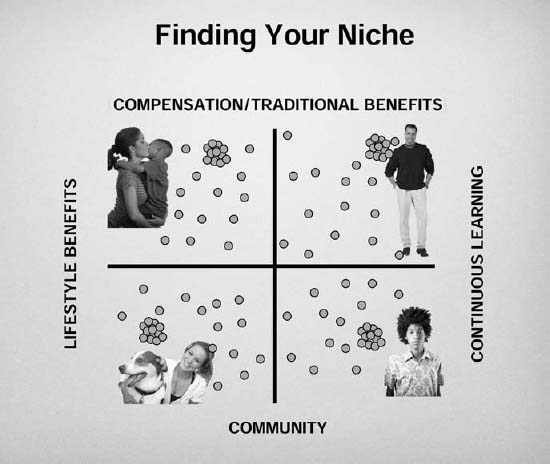

When attempting to satisfy worker needs, it is increasingly clear that you must first identify worker wants. Not all workers want the same things. For example, the employee value proposition that might appeal to college students may not be as attractive to baby boomers. Instead of trying to appeal to everyone, and in the process satisfying no one, successful companies are taking a novel approach to recruiting and providing for their employees. They carefully identify their target worker audience and then appeal directly to that crowd. As Mark Penn, political strategist and co-author of Microtrends, writes, “The power of individual choice has never been greater, and the reasons and patterns for those choices never harder to understand and analyze. The skill of microtargeting—identifying small, intense subgroups and communicating with them about their individual needs and wants—has never been more critical… . The one-size-fits-all approach to the world is dead.”11

Many examples can be found of successful companies that attract and keep great employees because they are successful in following a niche strategy. For example, Figure 3.8 on the facing page lists several highly successful programs.

These companies have discovered underserved and untapped sources to recruit, satisfy, and retain managers and employees. There’s a recognition that different groups of people have different needs, as shown in Figure 3.9. By identifying and satisfying these groups individually, companies can create a pool of happy, loyal, and satisfied employees.

Figure 3.8. Companies that have customized employee programs.

Source: People Report, 2009.

The foodservice industry is, at its core, just that—an industry founded on service. When the employees serve the guests, and the employer serves the employees, everyone’s needs have been met and the foundation is laid for continued growth and success.

Conclusion

Our research indicates that leading companies have long since moved past relying on traditional compensation and benefits offerings to attract and retain a quality workforce. Instead, they operate with a focus on “total rewards,” offering a combination of competitive compensation and benefits, flexible schedules, lifestyle rewards, switched-on training programs, an inclusive workplace, and a commitment to lifelong learning. These same companies think creatively about how they recruit new employees to join them. They cast wide nets that encompass women, minorities, students, retirees, and candidates from other industries. They count on referrals and recognition as a great place to work to attract candidates to their doors. These approaches enable proactive operators to meet the challenge of the times. Change is imperative, and in both the near and longer term, human capital excellence will be a textbook advantage for the winners in this marketplace.

Figure 3.9. Employee niche needs.

Source: People Report, 2009.

Notes

1.Roger Herman et al., Impending Crisis: Too Many Jobs Too Few People (Winchester, Va.: Oakhill Press, 2003), 2.

2.Comparable Store Sales. Year over year sales increase/decrease in units operating for a full twelve months.

3.Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert I. Sutton, Hard Facts, Dangerous Half-Truths & Total Nonsense: Profiting From Evidence-Based Management (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2006), 123.

4.Adrian Gostick and Chester Elton, The Invisible Employee: Realizing the Hidden Potential in Everyone (Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, 2006), 24.

5.Ian Ayres, Super Crunchers: Why Thinking-by-Numbers Is the New Way to Be Smart (New York: Bantam Books, 2007), 28.

6.People Report Survey of Unit Level Practices, Dallas, 2007.

7.Bill Catlette and Richard Hadden, Contented Cows Give Better Milk: The Plain Truth About Employee Relation and Your Bottom Line (German-town, Tenn.: Saltillo Press, 2001), 7.

8.Gostick and Elton, The Invisible Employee, xv.

9.Catlette and Hadden, Contented Cows, xiv.

10.Pfeffer and Sutton, Hard Facts, 68.

11.Mark J. Penn and E. Kinney-Zalesne, Microtrends: The Small Forces Behind Tomorrow’s Big Changes (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2007), xi.

MORE THAN COMPENSATION: ATTRACTING, MOTIVATING, AND RETAINING EMPLOYEES, NOW AND IN THE FUTURE

Ryan M. Johnson

It has become clear that today’s battle for employee talent involves much more than well-designed or competitively generous compensation and benefits programs. While these programs can undoubtedly be critical, the most successful companies have realized that they must take a broader, more holistic look at the factors involved in attraction, motivation, and retention. Further, they know they must deploy all of these elements— compensation, benefits, work life, performance management, recognition, employee development, and career opportunities—in unison with their strategic advantage. Indeed, the organizations that integrate these traditionally disparate elements into a “total rewards” philosophy will be the most competitive organizations in the coming decades.

Total rewards: All of the tools available to an employer that may be used to attract, motivate, and retain employees. Total rewards can include anything the employee perceives to be of value resulting from the employment relationship.

Some Historical Context

For centuries, the basic premise of the employer-employee relationship has been the same: An individual (the employee) provides his or her time, talent, and/or effort to an organization and, in exchange, the organization (the employer) reciprocates with compensation or pay. Despite the long-term stability of this exchange relationship, many employers have struggled in recent decades with a core question: Is pay by itself adequate to effectively attract, motivate, and retain employees?

Fifty years ago, when the fields of compensation and benefits were emerging, the prevailing practices in most companies were based on simple formulas that served the entire employee population. Pay or salary “structures” were just that—rigid and highly controlled—and benefits programs were designed as a one-size-fits-all for a mostly homogeneous workforce. In the 1970s and 1980s, however, the workforce began to change in fundamental ways, and employers began to face a new competitive landscape. As households began shifting away from the sole-breadwinner model that had been prevalent in the 1950s and ‘60s, new government mandates related to employee benefits were becoming law, and huge multinational firms were emerging in an increasingly global competitive environment.

Collectively, these forces and others caused business leaders to seek new ways to improve their talent and labor practices. Personnel or HR professionals—particularly those specializing in compensation and benefits—were challenged to contain costs and contribute to improved business results. It did not take long for many to realize that incremental improvement of one-size-fits-all pay and benefits programs would simply not be enough. New vehicles for delivering compensation, like variable pay and equity—most often limited to the most senior executives—were introduced.

By the 1980s, forward-looking professionals were recognizing that bringing together compensation and benefits, and thinking holistically about them, could create advantages in recruiting. Soon, some organizations were talking about their “total compensation” package in an effort to provide a competitive advantage in attracting and retaining talent. Certainly, increased efficiencies and cost controls were the mandate for survival, but many organizations recognized that an integrated and enriched “value exchange” between employer and employees could accelerate business success.

By the mid-1990s, the holistic concept had evolved again, in response to an ever-changing business environment. The first notions of “total rewards” were advanced as a new way of thinking about combining both the tangible and intangible levers that employers could use to successfully attract, motivate, and retain employees.

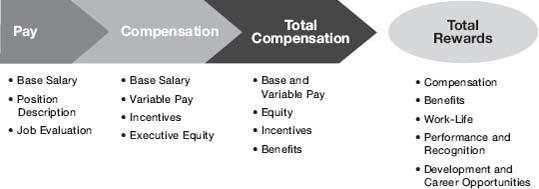

The Evolution of Pay to Total Rewards

Since the late 1990s, a handful of different total-rewards models have been published by consulting firms, thought leaders, and the nonprofit association for total-rewards professionals (WorldatWork). While each approach presents a unique point of view, all of the models recognize the importance of thinking holistically and of leveraging multiple programs, practices, and cultural dynamics to satisfy and engage the best employees and, ultimately, to contribute to improved business performance and bottom-line results, as shown in Figure 3.10.

The Role of a Global Association

As the global association representing the various professions that make up the field of total rewards, WorldatWork has served as a focal point for intellectual-capital development and dialogue about this topic. In 2000, after facilitating a discussion with leading thinkers in the field, WorldatWork introduced its first total-rewards framework intended to advance the concept and help practitioners think and execute in new ways. The model focused on three elements:

1.Compensation

2.Benefits

3.The work experience: acknowledgment, balance (of work and life), culture, development (career/professional), and environment (workplace)

Figure 3.10. The concept of total rewards.

Until the late 1990s, this association of professionals had focused solely on compensation and benefits. Yet, specialists and generalists alike agreed that compensation and benefits—while foundational and representing the lion’s share of human capital costs—could not be fully effective unless they were part of an integrated strategy of other programs and practices to attract, motivate, and retain top talent.

Thus, the “work experience” aspect of the association’s first total-rewards model included aspects of employment that could have been either programmatic or part of the overall workplace experience. For instance, recognition or acknowledgment could come in the form of a formal rewards program or be as simple as a verbal “thank you” from the boss or co-worker. Similarly, workplace flexibility could manifest itself as a formal telework program with policies and procedures or be simply an organizational culture and practices that embrace concepts of a balanced work-life relationship.

The Association’s First Total-Rewards Model (2000)

During the early 2000s, as companies became exposed to the total-rewards concept, understanding of the concept advanced and more organizations began to adopt the philosophy. By mid-decade, survey data from WorldatWork members revealed that professionals were primarily using the terms total rewards, total compensation, or compensation and benefits to describe the collective strategies deployed by their companies to attract, motivate, and retain talent, as shown in Figure 3.11.

But a study by Deloitte in the same year showed the concept still in growth mode in terms of its adoption in the corporate world.1 In response to a survey question about how “employee total rewards” was being defined in their companies, a 56 percent majority viewed it somewhat narrowly, as “compensation, long-term incentives, and all other cash-based items.” Only 11 percent of Deloitte respondents defined “total rewards” as “all possible financial and nonfinancial factors affecting an employee’s experience, including corporate communications, deployment, job training, etc.”

In response to another question, almost two-thirds of respondents said they were exploring the possibility of managing rewards components in an integrated fashion or at least were interested in the concept.

Taking Total Rewards Further

During the past decade, while the concept of total rewards was gradually being adopted by leading organizations, practitioners were beginning to experience the power of leveraging multiple factors to attract, motivate, and retain talent—high-performing companies were able to watch the concepts in action. At the same time, human resources professionals, consulting firms, service providers, and academic institutions made steps toward the notion of total rewards.

Figure 3.11. First total-rewards model.

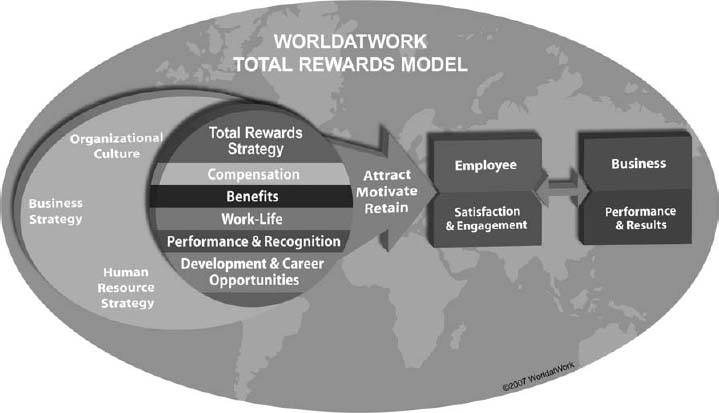

After more than a year of research and input, WorldatWork published an updated integrated total-rewards model in 2006, which reflected the next generation of thinking about total rewards. As with the first model, the second model placed total rewards in a context, presented a perspective to the profession, and championed the delicate art and science of combining five elements to achieve optimum business results, as shown in Figure 3.12.

The new model contained five total-rewards elements, each of which included programs, practices, elements, and dimensions that collectively defined an organization’s strategy to attract, motivate, and retain employees. The five elements were: compensation, benefits, work life, performance and recognition, and development and career opportunities.

On a practical level, the five elements represented a toolbox from which an organization could select to offer an employee value proposition that created value for both the organization and the employee.

The five elements were not mutually exclusive. Nor were they intended to represent the ways companies organize or deploy programs and the functions within them. For instance, performance management may be driven by a compensation function or may be decentralized in line organizations; it can be managed formally or informally. Likewise, recognition can be considered an aspect of compensation, benefits, and work life.

Figure 3.12. Second-generation total-rewards model.

In the six years between 2000 and 2006, both the thinking and practice of aspects that had constituted the work experience evolved considerably. It was important to recognize this evolution in the 2006 model and categorize its work-life element. Other portions of what was formerly considered the work experience became the context in this new model.

The Second Total-Rewards Model (2006)

The second-generation model recognized that total rewards operate in the context of overall business strategy, organizational culture, and HR strategy. Indeed, a company’s unique culture or exceptional brand value may be a critical component of the total employment value proposition. The backdrop of the model is a globe, representing two concepts: (1) that the model’s conceptual framework is applicable on a global basis; and (2) that there are external influences on a business, such as legal and regulatory issues, cultural factors and practices, and global competition.

An important dimension of the model is its “exchange relationship” between the employer and employee (the two-way arrow). As noted at the outset, successful companies realize that productive employees create value for their organizations in return for tangible and intangible value that enriches their lives. That has always been the essence of the exchange between employer and employee, and the model predicts that it will continue to be the case.

Compensation: Includes fixed (base) pay and variable pay (pay at risk). Also includes several forms of variable pay, such as short- and long-term incentives. The most traditional element in total rewards and a key to business success.

Benefits: Programs that protect employees and their families from financial risks. Includes traditional programs such as medical, dental, and retirement, as well as newer, nontraditional programs such as identity theft and pet insurance. During the past decade, this element of total rewards has been challenging for U.S. companies, owing to ever-rising health-care premiums and seemingly shrinking health-care benefits. For at least a decade, businesses have been trying to redefine the traditional benefits program.

Work Life: Any programs that help employees do their job effectively, such as flexible scheduling, telecommuting, and child-care programs. Has become one of the most talked-about areas of total rewards, garnering substantial media attention. Some organizations have indicated that work life is the “secret sauce” to their success in attracting, motivating, and retaining talent.

Performance and Recognition: The alignment of organizational and individual goals toward business success. Recognition is a way for employers to pay special attention to workers for their accomplishments, behaviors, and successes. It reinforces the value of performance improvement and fosters positive communication and feedback. Recognition can be programmatic or cultural in its execution.

Development and Career Opportunities: The concept of motivating and engaging the workforce through planning for the advancement and/or change in responsibilities to best suit individual skills, talents, and desires. Tuition assistance, professional development, sabbaticals, coaching and mentoring opportunities, succession planning, and apprenticeships are all examples of career-enhancement programs.

The Key to Success: Attract, Motivate, Retain

In aggregate, the five elements—or however many elements are represented in another total-rewards model—represent the levers that organizations (and total-rewards professionals) can pull and push to successfully attract, motivate, and retain employees. They are the items the employer exchanges in the exchange relationship.

Obtaining an adequate (and perpetual) supply of qualified talent is obviously essential for an organization’s survival. In many cases, attracting the right employees is a key plank of the business strategy. One way an organization can accomplish this is to determine which “attractors” within the various total-rewards categories bring the kind of talent that will drive organizational success. Attraction strategies can vary widely among industries and companies, and can be substantially different owing to workforce demographics. For instance, older, retired Americans might be lured back into the workforce if the company offers strong health-care or prescription-drug benefits, rather than generous cash compensation. On the other hand, software or gaming companies might offer more cash and relatively light health-care benefits to attract a younger, generally more healthy demographic.

Regarding retention, an organization’s long-term success can hinge on keeping employees who are valued contributors for as long as is mutually beneficial. Desired talent can be retained by using a dynamic blend of elements from the total-rewards package that reflects employees’ needs and lifestyles as they move through their career. However, not all retention is desirable, which is why development of a formal retention strategy is essential.

Finally, the concept of total rewards strives to cause employees to behave in a way that achieves the highest performance levels. Motivation comprises two types:

1.Intrinsic Motivation. Linked to factors that include an employee’s sense of achievement, respect for the whole person, trust, and appropriate advancement opportunities, intrinsic motivation consistently results in higher performance levels.

2.Extrinsic Motivation. Most frequently associated with tangible rewards such as pay, working conditions, co-worker relations, benefits, and such.

Applying a Total-Rewards Model

How can total-rewards professionals apply these concepts to their everyday business practices? Using a fictional Fortune 500 company as an example, I show how attracting, motivating, and retaining talent can— and should—take many forms.

For example, if the company is a high-tech software manufacturer, teleworking may be necessary to the overall business environment. In fact, with knowledge workers, the absence of a telework program could mean an inability to attract future talent, which certainly affects the bottom line. In addition, surveys, conversations with individuals, and analysis of employee demographics may lead total-rewards professionals to realize that those high-tech knowledge workers could be far better motivated by stock options than by substantial health insurance benefits. Thereby, the company measures and molds its total-rewards strategy to fit both workers and organizational needs.

In tailoring a total-rewards program, the savvy human resources professional will need input from both line managers and colleagues before defining a strategy, implementing it, and measuring its success. For example, work life may be viewed as a separate function in some organizations, while other organizations may consider it a component of the benefits strategy.

Where Is Total Rewards Headed?

The membership database of WorldatWork has yielded information on the evolution of job titles, as explained earlier, but there is also anecdotal evidence that some companies are beginning to brand their own versions of total rewards—a type of “internal branding” that seems the next move in this field.

While Notre Dame University promotes total rewards to its employees, the pizza company Dominos encourages employees to get their “piece of the pie,” referring to its variety of rewards programs. Reportedly, the company extends the pizza analogy to its employee collateral materials, showing how various elements of its programs can be combined to customize a “benefits pizza.” Starbucks has branded its total-rewards concept as “your special blend,” again, making an obvious play on its coffee products. “Your special blend” indicates the ability that employees have to customize their total-rewards offering.

In the battle for employee talent that will dominate tomorrow, companies like Starbucks and Dominos are well positioned to compete because they have removed some of the organizational procedures that, in the past, might have led the organization simply to throw more money into the compensation silo, hoping that would solve the retention issue. Branding their own total-rewards programs gives them the flexibility to adapt, thereby meeting the needs of the four generations of workers who will be their future talent pool. But whether it’s a branded program or not, organizations that integrate flexibility into their benefits programs, combining the traditionally disparate elements into a total-rewards philosophy, will be the most competitive organizations in the coming decades.

Note

1.2006 Employee Rewards Survey: The Next Generation, 5.

“BEST IN BRAZIL”: HUMAN CAPITAL AND BUSINESS MANAGEMENT FOR SUSTAINABILITY

Rugenia Pomi

For the past fourteen years, Sextante Brasil has published the Brazilian Human Capital Management Survey, aimed at understanding the discriminators on people management among the best companies in Brazil. This survey has come to be regarded as the prime source of quantitative and qualitative data on strategic positioning of human resources in Brazil. Based on the data, in 2007 Sextante Brasil created the Best in Brazil Seals for Human Capital and for Business Management for Sustainability to acknowledge and recognize companies that presented the best results in these areas. The companies’ scores in the Brazilian survey are based on the following pillars:

![]() Business value creation

Business value creation

![]() Safety and health

Safety and health

![]() Labor and union relationships

Labor and union relationships

![]() Retention

Retention

![]() Equity and internal income distribution

Equity and internal income distribution

![]() Learning, training, and development

Learning, training, and development

![]() HR professionals and HR team

HR professionals and HR team

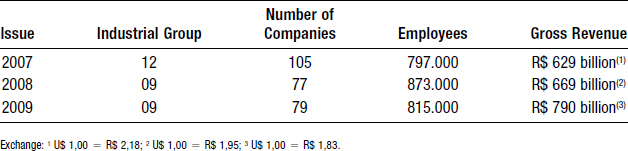

These seven pillars are detailed in seventeen specifics themes, and to be nominated companies need to reach a minimum 70 percent of the criteria shown in Table 3.1.

The companies that have achieved minimum 70 percent in each of those criteria have their scores audited by an independent consultancy company in order to be on the short list for the award, as shown in Table 3.2.

The years 2007 through 2009 represented a period of intense mergers and acquisitions. Table 3.3 lists the companies that have been awarded the seal.

The Essentials

In the age of knowledge, people—their hands, minds, and souls—are the most important assets in a company. The return on investment that an organization gets from its employees depends entirely on human actions, including its managerial capabilities. In the surveys conducted by Sextante Brasil, it becomes obvious that behind the excellent financial and market results of these best companies is a set of values and principles that guides management practices. The qualitative survey identified how these managerial practices are organized and implemented.

Company Mission, Vision, and Values

Each of these companies is clear about its mission, vision, values, and principles. The identified values include:

![]() Respect for the internal and external client

Respect for the internal and external client

![]() Innovation

Innovation

![]() Respect for the employees

Respect for the employees

![]() Individual and group responsibility

Individual and group responsibility

![]() Common good

Common good

![]() Commitment

Commitment

![]() Ethics

Ethics

![]() Respect for the environment

Respect for the environment

Table 3.1. Specific HR themes for Best in Brazil Seal.

| Profitability | >=50% |

| HCVA per capita | >=50 |

| Investments on labor injury prevention | >=75 |

| Labor injury followed by medical license | <–25 |

| Severity of labor injury | <–25 |

| Occupational disease | <–25 |

| Overtime | <–25 |

| Labor suit | <–25 |

| Solidarity on labor suit | <–25 |

| Liability suits | <–25 |

| Voluntary dismissal | <–25 |

| Seniority | >=50 |

| Income equity (CTP) (remuneration) | <–50 |

| Internal income distribution (PLRE) results and profit sharing | <–50 |

| T&D investments | >=50 |

| T&D hours | >=50 |

| HR specializations | Specialist professional |

| >= Management and administrative |

Table 3.2. Candidates for short list.

Table 3.3. Winners of the Best in Brazil Seal, 2007–2009.

In each case, it is considered critical that (1) all employees understand and, furthermore, commit themselves to the company’s mission and vision; and (2) that they put these values into daily practice.

For these companies, HR is responsible for communicating these principles to every new employee, ensuring full understanding and maintenance. Management has the responsibility to disseminate and guarantee these practices in all levels of the organization. In practice, there is costant focus on adding value to all that is done. The realization of growth, shareholder return on investment, reputation enhancement, and sustainability of market share are reflected in the day-to-day actions and in the satisfaction of internal and external customers.

Furthermore, people management is the main pillar of the HR business. There is a connection across the HR department to all staff areas and business units. All units share the company’s values. HR takes part in the company’s strategic planning and, based on that planning, defines and rolls out its own supporting action plan.

Human Resources Strategies and Best Practices

The role of HR is to attract, maintain, develop, and retain people; strengthen attitudes and behaviors aligned to the company’s strategy and culture; and give meaning to work, generating pride in the team’s accomplishments, facilitating organizational changes, and fostering learning and human growth via new scenarios aligned to values and company culture.

HR’s purpose, then, is to add value to the business and to its internal customers, employees, and managers. It is expected by the top executives, managers, and employees in general. HR pursues the following points of excellence:

![]() Alignment focused on the company’s strategic planning

Alignment focused on the company’s strategic planning

![]() Speed in problem solving

Speed in problem solving

![]() High quality in techniques, methodologies, systems, and people support

High quality in techniques, methodologies, systems, and people support

![]() Information system to properly support strategic decisions

Information system to properly support strategic decisions

People are considered and managed as essential to support the business, which is fundamental to the success of both employees and the company. The transparency in all actions is also common in HR departments, though they adopt different processes, programs, and systems to attract and retain excellent people who are committed and engaged with the company through the following:

![]() Integration and company culture acquisition

Integration and company culture acquisition

![]() Performance development and evaluation

Performance development and evaluation

![]() Internal acquisition, career, and succession

Internal acquisition, career, and succession

![]() Leadership development

Leadership development

![]() Climate management and quality of life

Climate management and quality of life

![]() Communication: listen, listen, listen

Communication: listen, listen, listen

![]() Learning organization

Learning organization

A Partnership Between HR and Executives

The human resources function acts as a strategic partner for the line managers, without paternalism or philanthropy, and is perceived and valued for its contribution to the organization. In all of its actions, HR works with simplicity and objectivity. There are no superpower programs; everything is simple, professional, and tailored to the company’s needs.

In all of these best companies, leaders are responsible for people management and they share the final decisions with HR, which provides instruments, methodology, and systems to support the whole process.

Communications with the Employees

The best companies assume that communication is an integral part of achieving planned results. Key actions in this area are keeping the employees informed about all relevant matters, with speed and transparency, and evaluating the effectiveness of the ongoing process. There is freedom of expression in all levels, on all topics. Communications happen naturally and are multidirectional.

These best companies also understand that communication is not only an HR responsibility but also a function that the entire management team should be accountable for. Effective communications promotes engagement, respect, and commitment among employees.

Organizational Climate Management and Customer Service

All the best companies manage their organizational climate and show results above 80 percent for responses to the survey question, “Are you proud to belong to … ?”

HR, with the managers’ participation, reports the results of employee surveys to the internal community, implements action plans as a response, and monitors the project results. For all companies, it is important that there be a healthy relationship between the executives and employees, in all levels and directions. Solid leadership is fundamental in this process, as good internal relationships.

Sustainability Actions

All companies follow sustainability guidelines that are part of a complete chain linking the internal community, customers/consumers/suppliers, and the external community/society/environment. Guidelines for action start with employee participation: The social responsibility is shared, which enhances the employees’ feelings of “belonging.”

Going Beyond the “What” to the “How”

It is confirmed that management practices based on values and principles of sustainability lead to excellence in financial and social results. It is also evident that good companies wish to compare their results with their competitors. However, the best management practice is not always the same for those that operate in the same economic sector or in the same region. Best practices rely exclusively on an enlightened way of being, thinking, feeling, and wanting. This way is unique to each company.

It’s important to go further than what has been done, however. It’s imperative to understand how these results have been achieved. The “how” of good HR management naturally respects the individual company’s particular way of doing business, so knowing the culture of an organization is essential to ensuring people’s commitment to sustainable development. In these best companies, there has been a search for coherence between theory and practice. For them, success has been the result of healthy internal relations; engagement; and commitment to the common goal, a sharing of values and principles, and overall caring for the company.

More than systems and processes, it has been relationships that have made the Brazilian DNA workforce different. A good working environment and healthy relationships guided by respect and genuine interest promote the integration and strengthening of a group that feels proud to belong. Indeed, a group led by competent managers conjointly with a professional HR function can make a big difference, helping these companies achieve exceptional results. For this reason, they deserve the Best in Brazil Seal in People and Business Management.