Impacting Productivity and the Bottom Line: Ingram Content Group

Wayne M. Keegan, Chief Human Resources Officer

The Ingram Content Group (ICG) is part of a long tradition of successful companies built by the Ingram family. Dedicated to helping content reach its designation by providing a broad range of physical and digital services, Ingram has been a partner to publishers, booksellers, and libraries for more than four decades. ICG leads the industry in physical distribution, supply chain management, and fulfillment services with access to all markets both domestic and international. On average, ICG ships 2.4 million units each week to over 85,000 customers from four distribution centers.

Employee turnover had been a chronic problem for Ingram’s distribution and fulfillment division for years, rising steadily until it hit a rate of 81.7 percent enterprise-wide at the end of 2002, and 102 percent in our flagship distribution center in La Vergne, Tennessee. For Operations/Logistics leadership, the revolving door of talent was disruptive in its efforts to operate at best-of-industry standards. For the rest of the C-staff, the attitude was one of resignation—after all, these were tough, entry-level, blue-collar jobs in a warehouse/distribution environment with production standards. In essence, high turnover in the Operations groups was viewed as a fact of life.

Getting the Attention of Leadership

For Operations/Logistics leadership, excessive turnover was a disruptive factor in its efforts to effectively manage its facilities. Intuitively, we all knew that there was a significant human capital expense negatively impacting the bottom line. We were tracking the turnover data and benchmarking that against the data provided by the Department of Labor for Wholesale Trade. However, this practice alone was not capturing the financial impact of excessive turnover in terms that would allow management to make a cost/benefit determination of whether to focus the attention, resources, and efforts of the organization on this matter.

Initially, we explored two highly accepted methods for determining the cost of turnover: (1) capturing the individual expense items impacted by a separation event, and (2) using the more simple calculation of six months of base pay plus benefits for each nonexempt separation and one year for each exempt separation. However, while these are valid and widely used methodologies for calculating the cost of turnover, the expense numbers reported from these methods were such that they failed to pass the “reasonableness” test.

When outlining the expense implications to executive management of any human capital issue, the human resources leader needs to be aware that even C-staff or board leaders have a tipping point for reality, or reasonableness. Presenting a number that reaches a level where the sheer size, no matter how well laid out, simply shuts down the audience’s willingness to accept the number as valid will significantly reduce the chances of influencing that executive leadership on the need to take action. For example, in our case, the total number of nonexempt/hourly separations for 2002 in the Operations/Logistics group alone was 1,821. However, even if we adjusted to include only those separations that exceed the DOL’s Wholesale Trade benchmark, bringing the total down to 1,155, using the simple standard calculation at a rate of $26,000 per separation (base pay + benefits), we would be reporting a cost of excessive turnover for just this group of a little north of $30 million. Even for a company with top line sales of over $1 billion at the time, making a pitch that reducing turnover to the level of the benchmark would add $30 million to the bottom line would not pass the reasonableness test. Furthermore, we would have lost our audience and, more important, lost an opportunity to address a serious issue that was costing the company significant pretax dollars.

We knew that excessive turnover was disruptive to any efforts to maintain best-in-industry standards in the Operations/Logistics group, and we knew that this expense was a human capital loss significantly impacting the bottom line. The challenge we faced was to construct a formula that would capture the expense analytics used by the Operations and Finance groups in measuring operational performance. Therefore, we sought a formula that would establish a model for human capital value that could accurately identify the cost of excessive turnover, but also pass the reasonableness test in order to get the attention of senior leadership and to take action.

Crafting the Right Formula to Gain Leadership Support

Partnering with our Operations/Logistics colleagues, we analyzed the key operational and financial metric for their divisions: cost per unit, or CPU. Production standards had been established for the majority of the positions, so we evaluated the labor costs in relation to unit/line production standards.

From our collective experience, we knew that there was a significant gap between a tenured departing associate and a newly hired replacement regarding production output versus production standard. As a rule of thumb, we had accepted a thirty-day ramping-up period for the average new hire to perform at standard. However, this assumption had never been validated through a scientific production analysis. An analysis of the average production rates for new hires in 2002 revealed that the rampingup time in achieving the production standard was greater than assumed.

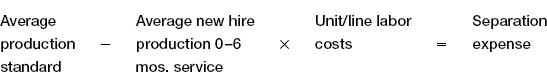

For every replacement of an associate with six months or more of service, who was averaging 106 percent of production standard, the newly hired replacement initially performed at an average of only 50 percent of standard, 83 percent at three months of service, 95 percent for the months three to six months, and finally achieving the production standard after six months of employment. Clearly, there was a dramatic drop in productivity for each separation incident, and the challenge was to craft a metric that would capture that financial impact. We came up with the following metric for our human capital value model:

Applying this formula, we found that the average cost of lost productivity was $3,652 per separation incident.

The Causes, the Metrics, and the Intervention Strategies

Knowing the expense of excessive turnover was half the battle. We needed to identify what factors were driving it, establish the metrics to measure the impact in order to determine which factors warranted our attention, then craft the intervention strategies and track the effectiveness of the strategies once they were implemented. All of these metrics were listed on the HR dashboard and communicated to leadership as follows.

A. Staffing

1. We established quality-of-hire metrics measuring turnover at ninety days and one year; we benchmarked this against data provided by the Human Capital Report from the Saratoga Institute.

2. Utilizing the Activity Vector Analysis (AVA) assessment tool, we identified the behaviors required for each of the roles that would enhance the potential for retention. We administered the instrument to all applicants, correlating their results against the role profile.

3. We implemented a robust screening process for all hourly positions, subjecting these applicants to the same level of scrutiny as we would middle-management positions in the company. In our flagship distribution center in La Vergne, Tennessee, in 2006, we screened 3,875 applicants and hired only 282, or 7 percent; in 2007, we screened 6,869 applicants and hired only 200, or 3 percent.

B. Leadership Development

1. Partnering with a local college, we delivered a tailored ongoing development program for all levels of management in the Operations/Logistics group, but with a series of programs specially focused on Team Leads and Supervisors, the critical links between the company and our associates, to ensure the effectiveness of the leadership team.

2. In partnership with the ICG Legal team, we delivered a series of learning events to enhance communication and to educate leadership on key issues that impact associates.

3. We assessed effectiveness of learning initiatives through follow-up evaluations measuring learning and on-the-job application of newly acquired knowledge, skills, and abilities, as well as continued management inventory assessments. Return on investment was evaluated through turnover reduction, increase in leadership skills as measured through continued management inventories, and internal ascendance.

4. We redesigned performance management to include a focus on turnover. A turnover reduction goal was added to every member of the Operations/Logistics management team, as well as the HR team, as part of their annual performance management reviews.

5. We established cross-functional turnover teams to create strategies, implement action items, and measure effectiveness as a means of achieving turnover goals.

C. Rewards

1. We ensured that base pay was competitive with local market conditions.

2. We implemented a pay-for-performance program system for the hourly team that was based on production and quality standards.

3. We secured their futures through education and communication of the importance of the 401k program. For the Operations/Logistics group during this five-year period, participation rose from 25 to 84 percent, surpassing the Wholesale Trade benchmark of 72 percent.1

D. Associate Relations

1. We established quarterly roundtables chaired by the executive for each department; notes were published, along with specific action items to be addressed.

2. We implemented a retraining program to assist associates who were struggling with production standards. Instead of treating associates who fell short of production standards as a disciplinary problem, we gave them an opportunity to improve through additional training.

3. Management and HR were trained to identify personal issues that may drive associates to leave, and to intervene as appropriate.

4. We increased employee engagement opportunities through inclusion on teams such as the Safety Committee and process improvement/LEAN teams.

Achieving Our ROI

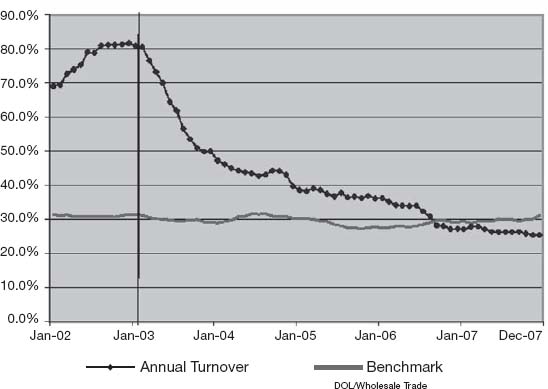

Within five years of implementing the strategies to address excessive turnover, turnover for the Operations/Logistics groups dropped from 81.7 to 25.5 percent, thereby achieving a cost savings tied to added productivity of $13.4 million over the five-year period. See Figure 7.1.

In our flagship distribution center in La Vergne, turnover dropped during the same period from 102 to 28.8 percent. See Figure 7.2.

In 2006, for the first time in the company’s history since 1999, when turnover had begun to be tracked, the Operations/Logistics group’s total turnover was less than the DOL/Wholesale Trade benchmark and, thus, reported the first year of no expense tied to excessive turnover. That accomplishment was repeated in 2007.

Figure 7.1. Operations turnover.

Figure 7.2. La Vergne distribution center turnover.

Productivity increases tied to the reduction in turnover and to the improvement in quality of hires during the five years of this study also allowed staffing levels to be reduced in the Operations/Logistics groups by 39.9 percent, or 913 associates, while volume in the distribution networks remained steady.

At the start of this study in 2003, new hires reached production standards on average at 180 days of hire; by the end of 2007, that number was reduced to 88 days. Additionally, the volume of staffing dropped 55.7 percent, from 1,799 hires in 2002 to 796 by 2007.

Final Thoughts

While the issue of excessive turnover has been addressed, we continue to focus on the quality of our hires in the Operations/Logistics groups in order to attract the best talent. We also continue our efforts to retain that talent by enhancing our onboarding process, ensuring that our rewards system and benefits are competitive, and through a robust communication program, ensuring that Ingram management never loses touch with its associates. In addition, we continue to ensure that those who have the most direct contact with the associates—our Team Leads and Supervisors—are provided with effective ongoing leadership development.

In the twenty-first century, maximizing a company’s human capital is a key competitive factor for success. If human resources leadership is to be effective and add value in support of this effort, they must operate as business leaders who happen to concentrate in the field of HR. The language of the C-staff and the boardroom is numbers. Analytics applied to human capital issues are essential in providing the predictive data that will allow leadership to manage this valuable asset more effectively.

Note

1.Profit Sharing/401k Council of America.