CHAPTER 4

CQ KNOWLEDGE

One of the best ways to deal with the ambiguity faced in multicultural situations is by learning more about cultural differences. Even though intercultural understanding by itself doesn’t equal effectiveness, it is an essential part of alleviating the confusion that often ensues from this kind of work. CQ Knowledge asks the question: Do you have the cultural understanding needed to be more effective cross-culturally? Growth in CQ Knowledge can significantly strengthen your effectiveness in a myriad of areas.

CQ Knowledge: The extent to which you understand the role of culture in how people think and behave and your level of familiarity with how cultures are similar and different.

Key Question: What cultural understanding do I need to be more effective cross-culturally?

Sana was born near Detroit, Michigan. Her parents came to the United States from Yemen in the late sixties to study at the University of Michigan. Her dad got a good job, and they ended up staying. Many more of their relatives followed. Last month was the first time Sana visited Yemen herself. She and Haani took a delayed honeymoon to the Middle East and visited Haani’s relatives in Jordan, then her family in Yemen, and ended with a few days by themselves in Dubai before coming home to pack up and move to Indianapolis.

Walking the streets of Sanaa and Amman, the capital cities of Yemen and Jordan, was surreal for Sana. For the first time in her life, she was surrounded by people who looked like her. She felt like she was home—sort of, anyway. In other ways, she felt like a complete outsider. Everyone seemed to make assumptions about her and Haani’s wealth, religious convictions, and views on U.S. foreign policy. After so many years of being stereotyped back home for being Middle Eastern, now they were feeling stereotyped for being “American.” During their last day in Yemen, all of Sana’s aunts sat her down and told her she must reconsider moving away from Michigan to this new city (Indianapolis). Her aunt scolded her, “How can you and Haani leave your families like this? It’s just not right, Sana. This is bringing great shame to us. You’re behaving like infidels.”

Infidels? Moving to Indianapolis from Detroit was very exciting for Sana and Haani. This was a chance to build a new home together. They came here because Haani was offered a two-year research fellowship with a large pharmaceutical company. Despite the small stipend, Haani knew this was a much sought-after opportunity. Sana had agreed to find a steady job to support them. She’s not too worried about finding a job because she’s always succeeded at whatever she set out to do. But the interviewing process is new to her. Before the move, she had worked for her father at his dental practice in Michigan.

This morning, Sana is interviewing for an administrative assistant position at a telecom company. She’s five minutes early for the interview but she has to wait a half hour before Robert, the CFO, brings her into his office. While waiting, she notices everyone is dressed casually. The receptionist says, “Gotta love casual Fridays!” Sana feels like people in Indianapolis stare at her head covering much more than they ever did in Detroit.

When Robert comes to greet her, she wonders why he’s wearing a suit and tie on “casual Friday.” She awkwardly shakes his hand, and he spends the first several minutes talking about his daughter, who is studying in Budapest. Just like my dad, she thought. He’s so proud of his daughter.

Out of the corner of her eye, Sana sees a plaque that says, “It’s not a religion. It’s a relationship.” Just then, Robert says, “So your résumé says you’re bilingual. I must say, you do speak really great English.” Then he asks, “So how long have you lived in the U.S.?” He seems taken back when she responds, “All my life.”

At the end of the interview, Sana says, “My husband would like to meet you. May I give him your number?” For the first time all morning, Robert seems speechless. Finally, he responds, “Let’s see how the interviewing process goes. If you’re back for a second interview, we can talk about it then.”

Robert has fifteen minutes before his next interview, so he pulls out the agenda for today’s big meeting regarding the potential acquisition by the Middle Eastern company. In thinking about the meeting, he wonders if there’s a tactful way to bring up what his friend Sharon told him last week over coffee. When Robert confidentially told Sharon they might sell one of their business lines to a successful Middle Eastern firm, Sharon said, “Just be careful. Business runs on a different set of rules over there.” She told him about a time when her colleague Alvin, a Singaporean manager from her company, was sent to the Middle East to establish a new regional hub for the business.

When Alvin arrived in the Middle East from Singapore, he went straight to the immigration office to deal with the necessary permits for conducting business there. Alvin was smartly dressed for his meeting with the immigration official. He completed the application impeccably and handed over the documents and corresponding fees. But he didn’t offer the official any kind of tip for getting this paperwork completed. He was confused when the officer said some additional paperwork was needed. Alvin brought everything the website said he needed and even called ahead to confirm that he was prepared.

Alvin went back two more times, and on each occasion, he became more irritated at the delays. But despite some broad hints dropped by the immigration officer, Alvin still didn’t offer any cash as a personal accommodation. So the officer persisted in his approach. If Alvin won’t play the game according to the established rules, he will have to accept the consequences.

As Robert listened to Sharon recount this experience, he said, “Well, that’s just corrupt. That isn’t a tip. It’s a bribe.”

“I know” Sharon responded. “That’s what we all thought. And we all have to sign agreements with the company promising that we won’t pay or accept bribes of any kind. But I guess that’s just the way business is done there. Immigration officers are paid a very low wage with the assumption that the individuals served will show their appreciation with small sums of money. I’m just saying, Robert, you better know what you’re getting into if you’re going to do business with a company over there. They play by different rules.”

But there’s no time for Robert to think any more about that right now. The next applicant just arrived for her interview—a loud-spoken woman with a strong southern accent. Oh, dear Lord, Robert thinks. Does HR do any screening before they send me these people?

WHAT’S CQ KNOWLEDGE GOT TO DO WITH IT?

CQ Knowledge is your understanding about culture and how it shapes behavior. This is the area most often emphasized in cross-cultural preparation—learning about cultural values and differences. Its importance cannot be overstated. As we learn more about cultures and different ways of doing things, it helps us better understand what’s going on, which, in turn, helps us relate and work more effectively.

There are so many ways enhanced CQ Knowledge could help Sana and Robert. We get a glimpse into Sana’s level of cultural understanding by the way she receives the criticisms from her Yemeni aunts and the nature of her questions and comments to Robert during their interview. And Robert’s conversations with Sana and his friend Sharon indicate something about his CQ Knowledge. A greater degree of CQ Knowledge will help Robert conduct a better, more effective interview, and it will help Sana be more successful in pitching herself to potential employers.

Again, CQ Knowledge asks the question: Do you have the cultural understanding needed to be more effective cross-culturally? The emphasis here is not on mastering all the ins and outs of each specific culture. If Robert was going to do a lot of extensive work in Yemen, he’d be wise to gain some very specialized understanding of the history, character, and cultural nuances of Yemen. But Robert can’t realistically become an expert on Yemen simply for a forty-five-minute interview. The most important part of CQ Knowledge is developing a richer understanding of culture, its influence on thinking and behavior, and the primary ways cultures differ.

With high CQ Knowledge, you have a holistic, well-organized understanding of culture and how it affects the way people think and behave. It begins with a strong sense of your own cultural identity and the way the cultures of which you’re part shape your behavior. When you have high CQ Knowledge, you possess a repertoire of understanding about how cultures are alike and different. You can encounter unfamiliar cultures and begin to understand a culture in light of your overall cultural understanding.1

ASSESSING YOUR CQ KNOWLEDGE

How is your CQ Knowledge? To what degree do you understand how cultures are similar and different? Based on the feedback report that accompanies the online CQ Self-Assessment, what overall CQ Knowledge score did you receive?*

Overall CQ Knowledge:__________

Did you rate yourself low, medium, or high compared to others who have completed the CQ Self-Assessment? (circle one)

![]()

From what you’re learning about CQ Knowledge in this chapter, are you surprised by the results? Keep in mind that the self-assessment is just one snapshot of your view of your CQ capabilities at a particular point in time. But it’s worth considering the results given the high level of reliability found in the assessment as used among individuals around the world.

In order to dig more deeply into your CQ Knowledge, the inventory also helps you assess your cultural understanding in the four specific areas of CQ Knowledge (business, interpersonal, socio-linguistics, and leadership). Extensive research has examined the way these various bases of knowledge influence your overall understanding and insight as you interact cross-culturally.2 Write your scores for each of the following and note the descriptions of these sub-dimensions.

Business (Legal and Economic Systems): _________

This is the extent to which you understand the various cultural systems that exist in places around the world (e.g., economic, legal, educational). It’s not simply for people in business, but it does refer to your knowledge of some of the different approaches used for business in various cultures. A high score means you have a good grasp of the various systems that exist among different national cultures. A low score means you have limited understanding about the varying economic and legal systems between one country and the next.

Interpersonal: _________

This is the extent to which you know about how cultures differ in their values, norms for social etiquette, and religious perspectives. A high score means you have a strong understanding of cultural values and how they play out in various contexts. A low score means you rated yourself low in your knowledge of the norms and values of various cultures.

Socio-Linguistics: _________

This is your understanding of different languages and your knowledge of various rules for how language gets expressed verbally and nonverbally in various cultures. A high score means you understand the rules for verbal and nonverbal behavior for many cultures and a low score means you don’t.

This is your level of understanding about how effective management differs across cultures. A high score means you rated yourself strongly in terms of your knowledge about managing people and relationships across cultures. A low score means you have limited understanding of how management and relationships differ from one place to the next.

These four sub-dimensions of CQ Knowledge—business, interpersonal, socio-linguistics, and leadership—are the scientific bases for the strategies that follow. You’ll see these sub-dimensions alongside the list of strategies at the beginning of the next section. Not every strategy fits perfectly with a single sub-dimension, but the strategies have been organized according to the sub-dimension with which they are most closely associated. Use your scores from the sub-dimensions of CQ Knowledge to help you pinpoint which strategies to use first (presumably, the strategies that go with the sub-dimension where you scored lowest).

IMPROVING YOUR CQ KNOWLEDGE

The following section is a list of strategies to help you improve your CQ Knowledge. All these strategies are anchored in science and research on intercultural knowledge and stem from the four sub-dimensions of CQ Knowledge (business, interpersonal, socio-linguistics, and leadership). The point is not for you to use all these strategies right now. There are many paths to increasing CQ Knowledge. Start with a couple that interest you.

1. STUDY CULTURE UP CLOSE

There’s no better way to learn about culture than when you’re in it. Culture is all around us and influences everyone and everything. But it’s easy to miss it if we don’t intentionally look for it. Adolescent researcher Terry Linhart traveled with a group of U.S. high school students to Ecuador to observe how they interacted with the local culture during their two-week trip there. He said their interaction with the Ecuadoreans was similar to how people act when they visit a museum. The students gawked at the “living artifacts” from Ecuador without really encountering them. The high schoolers performed for the Ecuadoreans, poured out affection on the children, and visited local businesses. However, with limited ability to understand the culture, and even less ability to speak Spanish, the students were unable to make accurate perceptions about the locals they encountered. Linhart writes, “Without spending significant time with the person, visiting his or her home, or even possessing rudimentary knowledge about the person’s history, students made quick assessments of their hosts’ lives and values.”3

When you encounter another culture, whether it’s a nearby neighborhood or a far-away city, immerse yourself in it and learn about the culture from the inside-out. Here are a few ideas for how you can study culture up close.

People Watch

When you’re in a public place, discreetly observe someone who comes from a different cultural background and observe what he or she does. Listen and watch longer than you would when watching people from a familiar culture. Look for similarities. What appears to be the same about how people interact with significant others, family members, strangers, and others? More important, what differences do you observe? What seems different about the body language, touch, pace, and behavior of the people you observe?

Attend Cultural Celebrations

Locate an ethnic organization in a community near you and attend one of its cultural celebrations. If at all possible, participate in the event rather than just observing from the sidelines. Ask someone to explain the significance of the activities, foods, and rituals. Get a group of friends to go to a Cinco de Mayo party together or attend a religious festival from a faith that is different from yours. If you’re invited to a wedding of someone from a different cultural background, by all means go—mostly to support your friend or colleague, but with the added benefit of learning about how the wedding ceremony takes place in this culture. Observe the way a funeral takes place among various cultures. If at all possible, ask an insider to explain to you what’s going on and the meaning associated with it.

Visit Grocery Stores

Find out where the locals shop and look at what’s on the shelves. Do this in ethnic neighborhoods in your own community as well as when you travel abroad. The products sold and the way they’re displayed provide some interesting cues about what’s there. Or go into other stores that target niche markets like older people, outdoor enthusiasts, or tea lovers.

Eat

Food provides a powerful window into culture. Go to restaurants with ethnically different foods and explore the meanings beneath the entrees. Are the foods served authentic or are they adaptations for the local pallet (e.g., the Chinese food served in many Western locations is significantly different from the typical fare in China. And in many years of traveling to China, I’ve yet to see a “takeout” box with wire handles or a fortune cookie).

Better yet, share a meal with someone who comes from the culture of the food you’re eating and see if he or she can offer some perspective about various dishes. A Thai friend might not be able to offer the history behind pad thai any more than you might know what’s behind some of your own cultural favorites. But at the very least, ask if your friend ate this growing up and what memories, if any, are associated with this dish.

Look at Art

Visit an art museum when you travel or simply notice the art that is displayed in public places. What kinds of pictures, if any, are hanging up in restaurants and stores? What do you see in people’s homes or in office settings? What can you learn about the culture based on the architecture and the layout of a city?

Notice whether solid, straight edges and moldings permeate interior design, architecture, and paintings. Or does the art reflect more fluid, seamless lines? Does the music follow a pattern with fixed pitches and precision, or is it more incremental and blurred?

I recently visited an art gallery in Melbourne, Australia, filled with Aboriginal art. This provided me with a whole different perspective on the indigenous people in Australia than what I’ve learned from books and lectures describing them. A painting, a sculpture, or a graphic novel portray norms of a culture that are hard to understand through words and language alone. We have to beware of assigning one artist’s portrayal to how everyone in that culture sees things. But art provides a multidimensional perspective on a culture.

There are countless other ways to learn about culture wherever you are. Roam the local streets, take in local events, and talk to taxi drivers. I love talking to taxi drivers wherever I go. They usually have strong opinions about almost everything. They’re watching and listening to various people all day long and hear things that aren’t meant for public consumption. Or talk with elderly people. Ask them how this place has changed during their lifetime.

Find ways to experience something more than the faux culture that exists in most places where you travel and instead, look for the authentic life of a place. For example, you can be at the Grand Palace in downtown Bangkok surrounded by thousands of camera-carrying tourists who linger at Starbucks and KFC. Or you can hop on a city bus and be instantly engulfed by locals without a tourist in sight. The real experiences are there to be had. You just have to seek them out. Free yourself from thinking you have to catch all the “must-see” attractions and go for the more authentic, local experiences. This is a fun and powerful way to increase your CQ Knowledge.

2. GOOGLE SMARTER

If you need information on anything—movie times, the temperature in Capetown, or how to deal with sinus pressure—the first default for many of us is Google, the source of all knowledge. Search engines and the Internet provide us with unprecedented amounts of information. And the vast resources on the Web can be powerful for enhancing CQ Knowledge. But how do we begin to wade through the endless information to gather input that’s truly helpful? How do we figure out whether the blog posted by someone about what’s going on in China is accurate?

Edna Reid, an expert in intelligence gathering, consults with leaders around the world to help them gather information that will truly enhance their CQ Knowledge. Reid teaches how to maximize the powers of Google. Let’s assume that you’re going to Qatar and you want to get more than just a Wikipedia or travel site description about the country. Here are a few ways to refine your search:

• To search specific kinds of sites related to Qatar, search using specific domain extensions (e.g., .org, .edu, .gov). Here are some examples:

• To search government sites with information about Qatar, enter: “Qatar site.gov.”

• To search educational sites (universities, etc.) with information about Qatar, enter: “Qatar site.edu.”

• To search Qatar-based sites about Qatar, search: “Qatar site.qa.”

• Remember that quotes limit the search to finding the exact combination of words you enter (e.g., “Qatar commerce” will find only information where those two words occur together).

• Next, wield the power of” Advanced Search” in Google. Here you designate much more specifically what you do and don’t want to have come up in your search results. The “Advanced Search” link is usually just to the right of the main search window on Google’s home page. A few examples of how you can do an advanced search:

• You can limit your search to only retrieving pdf documents by using the “File type” menu.

• You can search specific websites. For example, you can limit your search to anything written about Qatar on an IBM website.

• You can limit the date range in order to pull up only the most recent information or for a specific time period.

• Go to Google Scholar (scholar.google.com) to search academic and research-based material related to your topic. You’ll notice that the search results indicate the number of times the publication has been cited by others.4

With just a few more clicks and keystrokes, you can gain much more credible information from the Internet. When looking for country or culture-specific information, narrow your search to get more accurate and helpful information.

3. INCREASE YOUR GLOBAL AWARENESS

Global awareness is a crucial part of growing CQ Knowledge. It’s difficult to thoughtfully engage cross-culturally without a global perspective. Knowing that Singapore is not part of China and understanding that it’s not a land of squalor is an important (and elementary) point of understanding before engaging with a Singaporean or someone else from the region. Speaking about African countries as specific nations rather than making arbitrary statements about all of Africa as if Nigeria, Sudan, and Morocco are all the same place is again pretty basic, but it’s surprising how often this is a problem and the negative consequences that result.

In addition, a basic purview of major historical and current events around the world is important on so many levels. For one thing, when you know even the basic history between Japan and China, it makes you think differently about what might be going on when a Japanese and Chinese colleague are interacting. For years, Japan attempted to dominate China politically and militarily to secure its vast resources. It’s unlikely that a Japanese and Chinese colleague are consciously thinking about the historical dynamics between their nations every time they interact, but it might be implicitly shaping what occurs based on the “history” lessons they received growing up. And if you’re traveling to the country hosting the World Cup or during a major election there but never mention it, it will probably suggest an ethnocentric ignorance. You might think, I’m not being ethnocentric. I’m just not into sports or politics, but that’s not the point. Referencing these culturally significant events demonstrates some awareness and interest in what’s going on in the local setting.

It requires some intentional effort to increase your global consciousness because many news outlets only report on fads, trends, or events for a local market. And many families and educational systems spend little time teaching much value for understanding what’s going on around the world. But once again, an informed use of the Internet can pretty quickly offer some decent insights.

Americans, in particular, are notorious for our abysmal global consciousness. One of the things that fuels disdain for the United States is the sense that many American know little about the world beyond themselves.

Here are a few ways to enhance your global consciousness:

• Visit BBC news (http://news.bbc.co.uk/) for one of the more robust purviews of world events. The “In Pictures” link is one of my favorite ways to get a quick global purview of the day around the world.

• Read The Economist for a survey of current events internationally.

• Check out http://www.worldpress.org for a quick overview of current stories globally.

• Visit http://www.languagemonitor.com/ to see the top ten words of the year.

• Tune in to public broadcasting.

• Learn to ask good questions when you’re with people from different parts around the world. Most love to talk about their culture and share some of the timely news stories in the region.

There’s little excuse for global ignorance in today’s technologically connected world. There’s no need to be a walking newscast, but even two or three minutes a day spent scanning major global events goes along way in raising your CQ Knowledge.5

4. GO TO THE MOVIES OR READ A NOVEL

Literature and film provide a visceral way to see the world through someone else’s eyes. It’s one thing to understand the concepts and principles of culture described in nonfiction books like this one. But there’s another kind of insight and perspective provided by seeing how cultural dynamics impact the characters and subject matter of a good movie, novel, or memoir.

Almost any novel, memoir, or movie is filled with cultural dynamics because culture is everywhere. Notice how culture shapes what occurs. And look for storylines that specifically take place in a different culture. How does culture influence the way characters interact with their coworkers, friends, and family? How does conflict get resolved? Even if the story presents an inaccurate stereotype, you’ll encounter individuals who defy stereotypes in real life, too.

Stories provide a much more dynamic experience with culture than most principle-based business and professional books. And they’re much more true to how we experience culture—in the context of life, relationships, and a myriad of other circumstances. As you follow a story, think about how you would manage the various individuals. What if the lead character was your boss? How would you relate to her as a peer? To which characters are you most drawn? Which ones rub you the wrong way? How might culture explain some of these reactions?

As compared to when you’re actually interacting with someone from a different culture, books and movies allow you to be an observer rather than having to fully participate and worry about your effectiveness and potentially offensive behavior. You can sit back and observe what’s occurring. This gives you the mental reserves to study the influence culture has on what’s going on and to learn.

National Geographic contributor Daisann McLane suggests a twist on this idea by encouraging us to go to cinemas when we travel abroad to see the destination with new eyes. She writes, “I’ve had some of my most interesting experiences watching films ‘out of context.’ Like the times I was the only American in a youth club in Croatia showing Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and ended up explaining the slang.”6 And, of course, watching a Bollywood epic when you’re visiting Mumbai can provide a whole different level of insight into Indian culture—both the film itself and the experience of going to the movie. Go to a movie, read a good story, and enhance your CQ Knowledge in the process.

5. LEARN ABOUT CULTURAL VALUES

One of the most important strategies for growing CQ Knowledge is understanding a core set of cultural values. Cultural values are a society’s ideas about what is good, right, fair, and just. Researchers have developed a variety of ways to categorize these values in order to quickly compare one culture with another. We shouldn’t carelessly stereotype an entire culture with these values because there will be individuals and subcultures within a larger culture that are exceptions to these norms. But these values provide a helpful starting point for understanding cross-cultural relationships and situations. They give you an educated guess about how someone from a culture is likely to approach something.

The influence of these values is usually subconscious to most people within a culture—including ourselves. However, cultural values play a powerful role in shaping the thoughts and behaviors of individuals, organizations, and societies, regardless of whether they realize it. It’s neither better nor worse for an individual or culture to be one way or another along these values. But they do play a powerful role in how we live and work.

I’ve written more extensively about these cultural values in other books along with offering a deeper discussion about the leadership implications of each of them.7 But here’s a quick overview of some of the most important cultural values you should understand.

Individualism—Collectivism

The extent to which personal identity is defined in terms of individual or group characteristics.

Highly individualist cultures, such as the United States or Australia, emphasize the rights and responsibilities of the individual. Collectivist cultures like China and Jordan prioritize the rights and needs of groups.

Power Distance

The extent to which differences in power and status are expected and accepted.

Low power-distance cultures such as Israel and Canada diminish the significance of formal titles and roles and prefer flat organizational charts. High power-distance cultures such as India and Brazil think titles and clear authority lines are important indicators of how to relate and behave.

Uncertainty Avoidance

The extent to which risk is reduced or avoided through planning and guidelines.

Low uncertainty avoidance cultures such as Hong Kong and the United Kingdom have a higher tolerance and comfort with ambiguity and risk. High uncertainty avoidance cultures such as Russia and Japan look for ways to prevent uncertainty and risk.

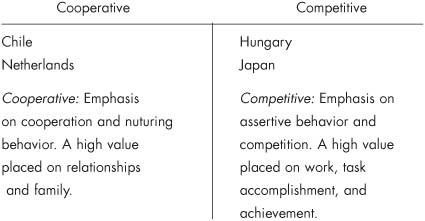

Cooperativeness—Competitiveness*

The extent to which achievement and competition are valued in contrast with a priority on social relationships and emotions.

Cultures that have a cooperative orientation such as Chile and the Netherlands value a more collaborative, nurturing approach to situations. Cultures with a more competitive orientation like Hungary and Japan have a more aggressive and assertive approach to life.

Time Orientation

The extent to which there’s a willingness to await success.

Short-term cultures such as Australia and the United States emphasize instant results. Long-term cultures such as South Korea and Brazil are more interested in long-term innovation and success, even if it means delayed gratification.

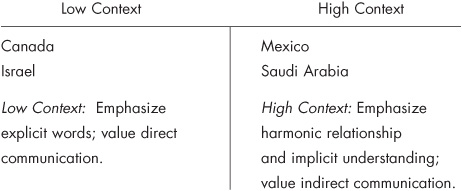

Context

The extent to which communication is direct and emphasizes roles and implicit understanding.

Low-context cultures such as Israel and Canada will usually post a lot of signs and directions and emphasize very direct, thorough communication. High-context cultures such as Saudi Arabia and Mexico presume individuals know how to get along more intuitively where explicit communication is unnecessary.

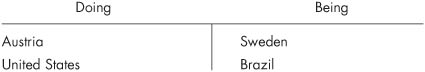

Doing—Being

The extent to which action and results are emphasized and valued.

Doing cultures such as the United States and Austria are extremely task-focused and outcome oriented. In contrast, being cultures such as Sweden and Brazil prioritize relationships and social networks and live for the moment.

These dimensions of cultural values are most often used to describe national cultures (e.g., the individualism of the United States versus the collectivism of Yemen). But the values may also apply to subcultures. For example, one business setting will use a very team-based approach to leadership and decision making (low power distance) and another will use a strong top-down structure (high power distance). The same is true among various generations, which often gravitate toward one direction or the other along these value sets.

Robert doesn’t have time to learn everything about Yemeni culture and even if he did, it might be largely irrelevant to Sana, given that she’s never lived there. But a broad understanding of the values often held by Arab Americans would help him ask much better questions in the interview and enhance his understanding of Sana’s responses. And if Sana uses cultural values to understand the subcultures of Indianapolis, the telecom company, and Robert’s background, it will at least give her a starting point for making sense of what she encounters.

Many resources (e.g., online, books, classes) provide a thorough explanation of cultural values with designations of where various nations lie along these continua.8 It’s increasingly difficult to characterize entire national cultures as being oriented one way vs. another, so we have to apply these values cautiously. But understanding the dimensions themselves is a vital tool for understanding some important ways that cultures differ. Just don’t overextend their use by assigning a cultural value to every situation and person in a particular culture. One of the most helpful ways to use these cultural values is to understand your own personal orientation in each of these areas. To learn more about taking an Individual Cultural Values Inventory, visit www.CulturalQ.com.

6. EXPLORE YOUR CULTURAL IDENTITY

None of us are merely objective observers of culture. We’re all products of culture, and we all play a part in advancing and morphing the cultures of which we’re part. As a result, another important strategy for growing your CQ Knowledge is to understand your own cultural identity. This is often the hardest culture to understand and see because it’s so ingrained in us, and it’s largely subconscious. We’ve grown up with a certain set of implicit rules and assumptions by which to live life and view the world and without CQ Knowledge, it’s easy to assume, that’s just the way the world is.

National cultures usually play the strongest influence in how we see the world. But other cultures where we’re immersed also play a profound role in how we think and behave.

Identify the cultures that most powerfully influence you. Address the following:

• What national and ethnic cultures have most significantly shaped you?

• What other subcultures have most powerfully shaped how you think and behave (consider subcultures like universities, the profession you’re in, your major at school, a corporate culture, religious affiliations, sexual identity, generational dynamics, physical disability groups, etc.)?

• Zero in on the one or two cultural contexts that most strongly define who you are today.

After you identify the cultures that have most powerfully shaped you, begin to think about questions like these in relationship to one or more of these cultures:

• What does “success” look like in this culture? How about failure?

• What professions have the highest salaries? Societies tend to pay the most money for what’s most valued (e.g., entertainers, government officials, cosmetic surgeons, etc.).

• What’s the role of family?

• How are decisions made?

• Who holds the most power?

• Who’s given more respect—the old or the young?

• Where does your country of origin fall along the cultural values listed in the previous strategy? How about other cultures that have been a significant part of your socialization?

Become a student of the history, rules, and norms of your culture. There’s little hope we’ll understand other cultures if we don’t first understand our own. This kind of understanding provides a basis for understanding and respecting the heritage and background of other people. Where do they fall along the cultural values continua?

Ethnocentrism—believing your own culture is the right and best way to go about life—is a major roadblock to CQ Knowledge. However, bashing and deprecating everything about your culture can be equally destructive. I’ve fallen into that trap. There are times I’ve loathed being a white male, a Christian, an academic, an American, and so much more. There are aspects to all those subcultures that are worthy of embarrassment. But there are virtuous elements within each of those subcultures, too. Sometimes, when we’re first exposed to different cultures and see our own culture through that new view, the tendency is to focus on all the negatives of our own culture. A commitment to understanding our own cultural background helps avoid either of these extremes and puts more emphasis on seeking to understand rather than evaluating the culture as good or bad.

Sana’s trip to the Middle East was as much about helping her learn about her own cultural identity as it was about understanding the Yemeni and Jordanian cultures. And Robert’s own background as a minority and a person of color could offer him significant insight into what’s behind some of Sana’s behavior and questions.

Your cultural background is a significant part of who you are, but there are some aspects of your identity that are unique from other individuals who share your cultural background. Examine how you’re like and unlike your culture. Identify the cultural values (from the last strategy) where you’re least aligned with your own culture. Do the same for other cultures with which you regularly come into contact. These are important insights because they’ll likely be the places where you experience the greatest degree of conflict and tension.

Intercultural researcher Edward Hall writes, “Culture hides much more than it reveals, and, strangely, it hides itself most effectively from its own participants. The real job is not to understand foreign cultures, but to understand one’s own”9 (italics added). Taking the time to explore your own cultural identity will enhance your overall CQ Knowledge.

7. STUDY A NEW LANGUAGE

Languages are so much more than words. There’s a clear connection between the ability to speak another language and your CQ Knowledge. Some say language is culture. The two are so seamlessly wrapped together that it’s difficult to have one without the other. Language allows you to interact with people and to pick up on all kinds of things you otherwise miss. The reverse is also true. Foreign language instructors teach students about the related culture because of the integral connection between the two. Environmental factors and societal norms shape the development of language and language further shapes culture. There’s a reason why there are so many different words for fish in the Norwegian language or for snow in Eskimo languages. Wei ji is the Chinese word for “crisis.” Wei means danger and ji means opportunity. This says so much about the dominant Chinese culture, a society that has always looked to leverage hardship into opportunity. Language yanks the blinds off the window of culture and allows us to take a much better look inside.10

Effective study of a new language should also include learning some of the most familiar nonverbal signals and behaviors used in a particular culture. The silent language of gestures and facial expressions is a critical part of growing your CQ Knowledge.

When interacting with someone who speaks a different language, there’s no substitute for learning some of the language itself. Not only does it inspire respect and gratitude, but it will help you understand how that person sees the world. We won’t be able to learn the languages of most of the cultures we encounter, but studying any new language can enhance your overall CQ Knowledge. In Chapter 6, I’ve included another language strategy where using a few key words or phrases in another language will help you behave much more successfully in places that speak that language.

8. SEEK DIVERSE PERSPECTIVES

Most adults pursue relationships and influences that support and reinforce their own perspectives and viewpoints. One of the most valuable ways to enhance CQ Knowledge is by intentionally seeking out diverse viewpoints. The goal isn’t just to minimize the differences to find out what you have in common. It’s to particularly look at and learn from the differences themselves.

This strategy is most helpful when you purposely find a cultural group that represents a set of beliefs or norms that are in conflict with your own. Attend one of their gatherings or events. Go to a religious service, a rave club, or a political gathering that is least aligned with your own preferences and seek to understand what’s behind the beliefs and behaviors of this group. Beware of hasty assumptions and suspend judgment for a while. Have coffee with someone who sees the world differently from you. Don’t go into it trying to persuade them to see it your way. Learn from your differences. Tune in to a news source that has a bias contrary to your own opinion. Pay attention to how it affects you. When I listen to volatile rhetoric about political issues that are contrary to my own, I feel my blood pressure go up. But the challenge here is to regulate that emotion so you can learn from a different perspective than the one you have.

You don’t have to abandon your beliefs and convictions. But for now, purposely put yourself into an uncomfortable setting. Convene a book club with people from varied cultural contexts. Think about how the varied cultural perspectives shape the ways individuals respond to the book. Or when given the choice to do a group project at work or for a class you’re taking, seek out someone from a different background to be your partner. Even if you’re from a similar ethnic background, find someone more conservative or liberal than you. If you’re an atheist, find someone deeply religious or vise versa. Commit to truly entering into dialogue together and learning from each other.

Another way to learn from diverse viewpoints is by finding a different news source than the one you typically choose. Whether driven from a contrasting ideology or originating from a different national culture, examine how the same event gets reported differently. Read the same story on Al Jazeera, NewsAsia, and BBC. And when you travel, look for ways to read a local newspaper. If you’re addicted to the Financial Times, South China Post, or USA Today, at least read it alongside a local paper and compare what gets reported in one as compared to the other. Skim all of it—advertisements, classifieds, public notices, and obituaries. You can gain a fascinating insight into a place by reading what does and doesn’t get reported in the local news.

The same strategy can be applied at home. In the words of President Obama to his fellow Americans, “If you’re someone who only reads the editorial page of the New York Times, try glancing at the page of the Wall Street Journal once in awhile. If you’re a fan of Glenn Beck or Rush Limbaugh, try reading a few columns on the Huffington Post website. It may make your blood boil; your mind may not often be changed. But the practice of listening to opposing views is essential for effective citizenship”11 (italics added).

9. RECRUIT A CQ COACH

A CQ coach, sometimes referred to as a cultural broker or guide, can be another integral part of helping us become more culturally intelligent. This is a strategy that will help in every area of CQ. But it fits best with enhancing our CQ Knowledge. When I first started working in the university setting, my friend Andrew already had several years under his belt as a faculty member. Even though he worked for a different institution, he helped me understand things like tenure, academic freedom, faculty governance, and much more. Friends like Naville, Soon, Soo Yeong, and Judy have spent years helping me understand Southeast Asia. My list of CQ coaches continues in places and cultures around the world.

A CQ coach can be a valuable asset in any cultural context. The challenge is finding one who can truly play that role. For example, sometimes outsiders, like an expat, can be a valuable guide because they too are bridging from another culture into this one. But I’ve also encountered expats who have very skewed, ill-informed understandings of the cultures where they live. Locals can be good coaches, but we also have to beware of assuming that the people who live in a culture make the best guides. They often lack the objectivity needed, too.

An effective CQ coach will use questions to guide us and offer support and feedback. It should be an individual who is careful not to oversimplify things while also offering some helpful, neutral stereotypes. Whoever it is, we have to remember the importance of not generalizing based on the advice we receive from any one individual. Intercultural expert Craig Storti says,

What [individuals] say may be true for people of their own age group, level of education, socioeconomic background (not to mention caste, religion, region or locality, sex, and experience) but not for other sectors of society. Ask a Montana rancher and a Manhattan banker what proper behavior or dress is at a dinner party and try to generalize from their answers!12

Select CQ coaches carefully. Some things to look for include:

![]() Can they distinguish what’s different about this culture from others?

Can they distinguish what’s different about this culture from others?

![]() Do they demonstrate self-awareness? Other-awareness?

Do they demonstrate self-awareness? Other-awareness?

![]() Are they familiar with your culture, including your national culture and your vocational culture (e.g., engineering or health care)?

Are they familiar with your culture, including your national culture and your vocational culture (e.g., engineering or health care)?

![]() Have they worked across numerous cultures themselves?

Have they worked across numerous cultures themselves?

![]() Do they ask lots of questions to help you discover the culture, or simply “tell” you?

Do they ask lots of questions to help you discover the culture, or simply “tell” you?

![]() Can they articulate what kinds of personalities often get most frustrated in this culture?

Can they articulate what kinds of personalities often get most frustrated in this culture?

A CQ coach with a good measure of multicultural awareness will serve you well. Reading an explanation about cultural issues in a book or going through a cross-cultural exercise is very different from receiving an explanation from someone who has lived through what we’re experiencing. Research indicates that expatriates and travelers who have cultural mentors fare better than those without them.13 One of the greatest things CQ coaches do is to help you know what kinds of questions you should ask of yourself and others as you move into this assignment.

BACK AT THE OFFICE

Sana would be better prepared for her interview with Robert and other managers in Indianapolis with a stronger understanding of the mainstream Midwest culture. Even though she’s lived in Michigan all her life, she’s been relatively insulated within the Arab American community surrounding greater Detroit. She should be careful not to stereotype Robert, but with some grasp of cultural values, she could at least think about whether Robert wearing a suit is a reflection of his African American values for dress and appearance.

If I were Sana, I’d be pretty taken aback by the confrontation with her aunts in Yemen. To feel defensive in that kind of situation is normal. But if Sana can see beyond the confrontation and think about how her lifestyle and upcoming move may appear through her aunts’ cultural lens, it might help her deal with the anger of being called an infidel. One of the things about CQ, though, is that it’s a two-way street. So Sana’s aunts would also be helped by some cultural understanding of life for Sana and Haani back in the United States. Before immediately making accusations, a greater degree of CQ Knowledge would, at the very least, allow them to approach the potentially offensive conversation differently.

As for Robert, even though he’s a minority, he seems ignorant that many other ethnic minorities have been born and raised in the United States, too. It’s bizarre, though commonplace, that he assumes Sana wasn’t born in the States. And if Robert knew more about the cultural values of individualism vs. collectivism, he might be less thrown off by Sana’s request to have Haani meet him. It would be a very reasonable request from a collectivist perspective for a spouse—and in particular, the husband in many Middle Eastern cultures—to want to know if he can trust his partner’s boss. Robert comes from a more collectivist culture himself, compared to the mainstream, dominant culture in the Midwest. But because of his marriage to Ingrid and having lived and worked largely in the dominant, professional culture for twenty years, he’s likely to be as much a product of that individualist subculture as of his more collectivist upbringing on the south side of Chicago.

And what about Robert’s friend Sharon advising him about the different rules for business in the Middle East—where her colleague Alvin was expected to pay a tip (bribe?) to get his paperwork processed? Sharon is right about one thing—business in different parts of the world operates by a different set of rules. We have to be careful to presume that different rules and practices are bad simply because they’re different or unfamiliar. But there’s good reason to be concerned about the many ethical dilemmas involved in a situation like the one that faced Alvin. Who is most responsible for Alvin’s dilemma—the immigration officer, the country that doesn’t pay the officer adequately, or other developed nations and their companies that don’t address this issue or who actually perpetuate the practice? Increased CQ Knowledge will caution Robert from stereotyping all Middle Eastern companies as operating this way. But it will also alert him to the idea that written policies, procedures, and contracts don’t have the same binding power in high-context societies as do commitments made through relationships and time spent together.

INCREASING YOUR CQ KNOWLEDGE

An abundance of information is available about various cultures. Don’t be overwhelmed. Start with a couple of these strategies to improve your CQ Knowledge. Then try another one.

Identify two strategies you can begin using to enhance your CQ Knowledge.