13. Strategic Planning in Outsourcing

13.1.2 The Role of Management in Outsourcing

13.1.3 What Are the Common Types of Outsourcing?

13.2 Strategic Planning and the Outsourcing Process

13.2.1 Relationship of Organizational Strategic Planning and Outsourcing

13.2.3. Risks in the Outsourcing Process

13.2.4 Risks in International/Global Outsourcing

13.2.5 Combining Outsourcing with Lean Strategy in Supply Chain Management

13.3 Other Topics in Strategic Planning in Outsourcing

13.3.1 Measuring Outsourcing Services

13.3.2 Outsourcing Benefits and Planning in the Product Life Cycle

13.3.3 Global Supply Chain Labor Standards in Outsourcing

Terms

Backsourcing

Business process outsourcing (BPO)

Business transformation outsourcing (BTO)

Continual renewal outsourcing agreement

Co-sourcing

Crowdsourcing

Culture

Fixed-term outsourcing agreement

Governmental ideology

Implementation provider-selection criteria

Multisourcing outsourcing

Nearshore outsourcing

Netsourcing

Offshore outsourcing

Qualitative provider-selection criteria

Quantitative provider-selection criteria

Reshoring

Shared outsourcing

Spin-off outsourcing

Transitional outsourcing

Value-added outsourcing

13.1. Prerequisite Material

13.1.1. What Is Outsourcing?

As organizations mature and grow, many find themselves with limitations on labor resources, services availability, materials, or other economic resource shortages in a particular geographic location. To compensate for these shortages, firms subcontract what they need from external sources or businesses. Sometimes these are geographically distant sources outside the contracting firm’s own country. Contracting for or procuring to meet these shortages represents the act of outsourcing if what is needed is acquired from a source external to the organization (that is, not owned by the client firm) (Krajewski et al., 2013, p. 369). International outsourcing involves activities between nations or the boundaries of two or more countries. When sources come from all over the world, they represent global outsourcing (Schniederjans et al., 2005, p. 5). Conversely, some firms keep all their production needs internal or use an internal strategy of insourcing. Insourcing is an allocation or reallocation of resources internally within the same organization, even if the allocation is from different geographic locations. In an outsourcing arrangement, a client firm seeks to outsource its internal business activities, and an outsource provider firm provides the outsourcing services or resources to the client.

13.1.2. The Role of Management in Outsourcing

The fundamental role of managers in undertaking an outsourcing project involves a balancing of allocating insourcing and outsourcing needs to serve the client firm. As shown in Figure 13.1, the balancing process is a function of the costs and benefits to the client firm. How much or how little outsourcing to use depends on balancing the organization’s perception of benefits in using this strategy and the risks associated with it.

Figure 13.1. Balancing outsourcing and insourcing benefits and costs

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, Figure 1.1, p. 4).

Outsourcing can be viewed as a strategy and can be used to achieve many organizational objectives (for example, cost reduction, risk reduction) in any area of business activity. All or part of any of the unique functional areas (for example, accounting, supply chain, information systems) that have been historically insourced can be outsourced. Outsourcing origins can be found in the historic use of subcontracting, which makes outsourcing not revolutionary but an evolution of business organizations (Schniederjans et al., 2005, p. 5).

13.1.3. What Are the Common Types of Outsourcing?

Some common types of outsourcing projects found in the literature are listed in Table 13.1. Strategically, outsourcing can be used as a change agent or a means of altering business organizations to better fit the needs of the client firm and its customers. For example, a business transformation outsourcing (BTO) project might entail a small educational change such as an in-house training session provided by an outsourced educational trainer to educate a client firm’s executives on supply chain legislation (outsourcing used as a change agent). However, business process outsourcing (BPO) might involve the complete outsourcing of all supply chain tasks to a third-party logistics (3PL) provider (a complete alteration of a client firm’s operations).

Table 13.1. Common Types of Outsourcing Projects

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, Figure 1.2, p. 8); Moser (2012).

13.2. Strategic Planning and the Outsourcing Process

13.2.1. Relationship of Organizational Strategic Planning and Outsourcing

The strategic planning process introduced in Chapter 1, “Designing Supply Chains,” begins with an organization’s mission statement, and then continues with general strategies at the organization-level that are segmented and given to individual departments as a basis to establish their own strategic departmental goals (see Figure 13.2). An organization-wide strategy of reducing costs to be more competitive in the market can be translated into an outsourcing strategy in a supply chain department as a desire to reduce costly inefficiency. This would be implemented by finding inefficient noncore competencies in the supply chain process, practices, policies, or tasks that might be better handled by outside outsource providers. The decision to use outsourcing to achieve goals is usually decided at the board of directors level in most organizations, based on finding the core and, more important, the noncore competencies from the external environmental analysis and internal organization analysis. Once the decision to use an outsourcing strategy is approved and accepted, the question of how much outsourcing is needed has to be determined. In situations where whole departments are outsourced (that is, business process outsourcing, BPO), the process would be handled by the CEO or vice presidents as needed. In less-invasive outsourcing efforts, the decision process is directed to the appropriate department. Experts from within and outside the organization are often employed to aid in making these assessments. Experts might be brought in to help in the analysis, including lawyers with international law backgrounds, international economics experts, and cultural experts from universities (Cavusgil et al., 2002, p. 83). During the analysis, board members may find the risks in some aspects of international outsourcing are too great. (We discuss international risks later.) They could change their minds on the outsourcing strategy or on some component of it (for example, a preference for going local, not global to find an outsource provider) and select a new strategy to achieve their goals. This new strategy may still involve international or global outsourcing, just not those aspects that are viewed as potentially too risky.

Figure 13.2. Relationship of strategic planning and outsourcing

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans (1998, Figure 2.2, p.22); Schniederjans et al. (2005, Figure 1.3, p. 10).

13.2.2. Outsourcing Process

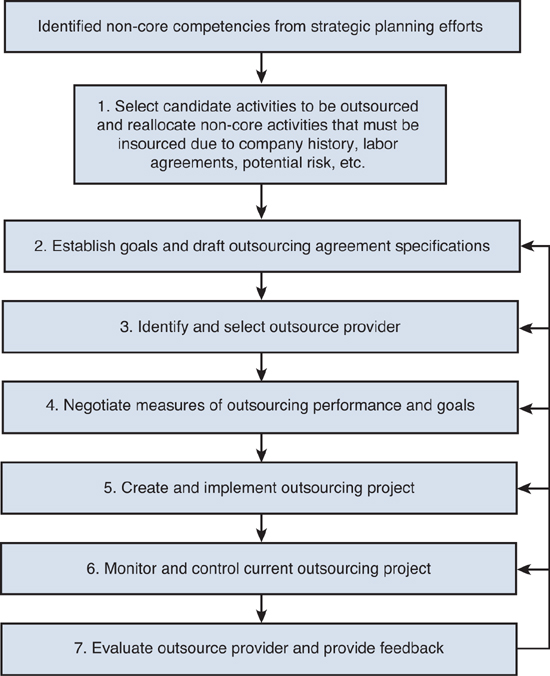

The process by which an outsourcing project is undertaken is much the same for either a fixed-term outsourcing agreement (that is, where there is a fixed, end-time period for the project), or a continual renewal outsourcing agreement (that is, the outsourcing provider expects to be doing the project indefinitely, resulting in an outsourcing program). The general steps in an outsourcing process used to implement an outsourcing project are presented in Figure 13.3 and described here:

1. Select candidate activities to outsource: Not every noncore competency identified will automatically be a candidate for outsourcing. Many of the noncore competencies, once recognized, can be dealt with by improving organizational weaknesses and insourcing them. Those that cannot be handled by insourcing means become ideal candidates for outsourcing.

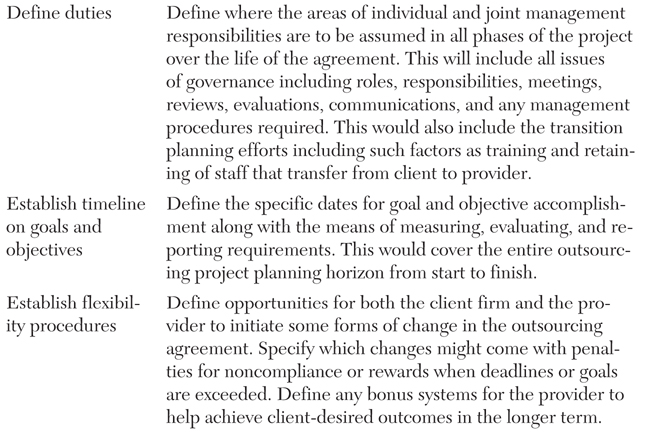

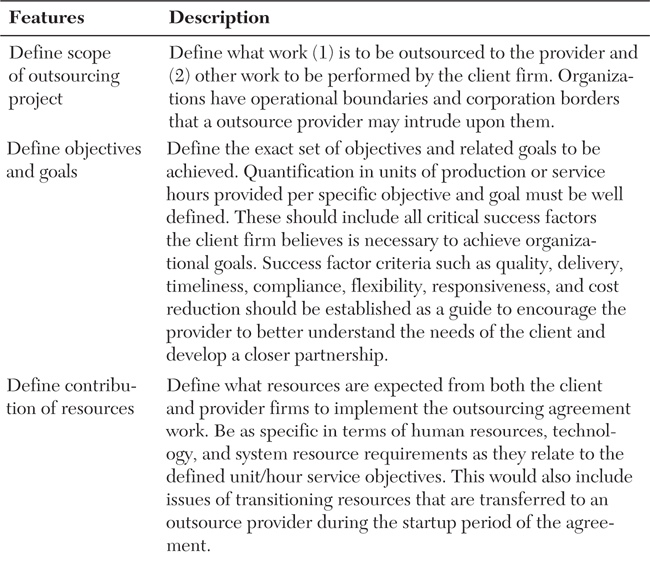

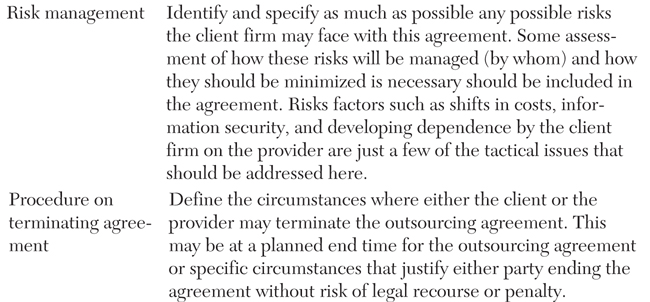

2. Establish goals and draft outsourcing agreement specifications: Once the noncore competency candidates are selected, goals are established in the context of the strategic objectives. For example, if a client firm had a strategic goal of achieving a market growth in sales of 25% per year over the next three years, that figure could be broken down into yearly targets. From that point on, existing client firm capabilities are determined on an aggregate yearly basis. What remains can be used to finally determine what needs to be stated in the outsource agreement. So the client firm would be in a position to start drafting it. Some of the typical outsourcing agreement specifications are presented in Table 13.2.

Figure 13.3. Steps in the outsourcing process

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, Figure 1.7, p. 14).

Table 13.2. Typical Outsourcing Agreement Specifications

Source: Adapted from Cullen and Willcocks (2003, pp. 67–111); Milgate (2001, p. 60); Schniederjans et al. (2005, Figure 4.2, p. 57).

3. Identify and select an outsource provider: Once a draft of the proposed outsourcing assignments is prepared, the next step is to find and select an outsource provider to do the work. Traditionally, a list of known possible providers can be prepared from industry association directories and outsourcing directories (FS Outsourcing Company, www.fsoutsourcing.com). From this list, referrals from experts or other experienced managers can be used in a systematic check-sheet needs and wants selection process to choose possible candidates. Another approach to identifying potential outsource providers is to establish a set of provider qualifications and use them to identify worthy candidates. Qualification criteria might be suited to support the particular needs of the client organization (for example, transportation connections and approved transportation permits in a targeted foreign market). The qualifications might include such criteria as excellence in service delivery, security, trust, flexibility, agility, and value. Pint and Baldwin (1997) suggest evaluating the outsource provider in terms of current capabilities to meet client needs; consideration of costs and risks jointly; knowledge; skills; breadth and depth of experience (including past performance); financial strength; and commitment to technological innovation, quality improvement, and customer satisfaction. Using these criteria, client firms can then make a request for information (RFI) proposal to individual outsource providers to conduct a preliminary evaluation to gauge the market for prevailing prices/rates or any criteria that is viewed as critical. A request for proposal (RFP) can also be used like an advertisement in outsourcing media stating the outsourcing requirements, including who is making the request, project scope, location of business activity, reasons for outsourcing, time horizons, and general pricing information. Both the RFI and RFP help to reduce the selection of an outsource provider, but additional effort is always needed to sort the best from the best and to make an optimal selection of a provider. Provider-selection criteria can be divided into four categories: obligatory, quantitative, qualitative, and implementation. Obligatory selection criteria (that is, must-have requirements to be considered eligible) include risk avoidance factors, English-speaking country, and so on. Quantitative provider-selection criteria and qualitative provider-selection criteria items found in the literature are used to judge the ability to satisfy (at least at some risk-rated level) the additional “niceties,” which a client firm might appreciate. Quantitative provider-selection criteria include such items as financial strength, high-quality service standards, adequate numbers of personnel to do the job, and so forth. Qualitative provider-selection criteria include such items as trustworthiness, outsourcing experience level, proven customer satisfaction, and so on. Implementation provider-selection criteria are focused on three phases of implementation related risk in the design, transition, and follow-up of outsourcing projects.

4. Negotiate measures of outsourcing performance and goals: The client firm is now in a position to begin negotiations for the actual outsource agreement that will clearly list specific goals and how goal accomplishment will be measured in using some form of performance indicator. For guiding principles in negotiating agreements, see Chapter 8, “Negotiating.”

5. Create and implement an outsourcing project: Once the agreement is negotiated, it can be put down on paper as a roadmap to implementation. The transition details for the implementation of the outsourcing project should be included in the agreement so that both parties know and agree to their responsibilities. Although most problems can be anticipated and planned for, many cannot. Therefore, provisions in the agreement must anticipate unexpected events and problems and provide a means for dealing with them during the implementation phase of the process. While the transition phase of implementation may be outlined in the outsourcing agreement, detailed human resource or staff assignments for both client and provider will need to be made at this planning step. The transition planning at the operational level should be very detailed and must cover human resources, facilities, equipment, software, third-party agreements, and all functions, processes, and business activities related to the outsourcing agreement. In addition, management responsibilities and functions of day-to-day planning, coordinating, staffing, organizing, and leading must be defined at this stage of the outsourcing process.

6. Monitor and control the current outsourcing project: After the transition from the client firm is made handing off the supply chain or other tasks to the outsource provider, the day-to-day efforts of implementing an outsourcing agreement are usually performed by middle-level and lower-level managers in both the client and the outsource provider firms. During this step in the outsourcing process, it is important to share information with those people who work in the areas where outsourcing is being implemented. Sharing the planning and implementation efforts is the best way to head off fear, suspicion, anger, or even disruptive behavior. As Elmuti and Kathawala (2) found in their study on international outsourcing, the number one reason for a negative impact on an outsourcing project was employees’ fear of the loss of their jobs. Other international factors such as cultural differences in work attitudes and differences in social norms might surface and reveal the need for education and desensitizing. Also, measures for monitoring ongoing goal achievement must be installed. Both the client firm and outsource provider must agree to measures that are to be taken: who collects information, where and to whom it is reported, and at what times both parties review the measures. These measures should be viewed as a quality-assurance system, which ensures the provider is doing the job it was hired to do for the client firm. Actually, a good monitoring system works for both parties. While the client firm uses the system to monitor goal achievement, the provider uses it to determine whether it qualifies for extra benefits for doing an exceptional job.

7. Evaluate the outsource provider and provide feedback: Based on the monitoring measurements and their comparison to the agreed levels of business performance, monitoring can become a routine process. This should be viewed as a continuous effort of the evaluation phase of the outsourcing process. The goal is to provide a timely system of checks on the outsource provider to the client firm to ensure compliance with the outsource agreement and the expectations of the client firm. Sharing information on the progress of the outsourcing project and providing feedback for corrective control and further improvements is essential for a successful outsourcing project. The evaluations of the outsource provider might also take the form of periodic audits performed by client firm’s staff or outside auditing firms. Greaver (1999, pp. 272–273) suggests an oversight council (that is, internal and external supply chain members who monitor and counsel a firm regarding issues that arise from the evaluation of suppliers) be appointed to review annual supplier performance. In addition, the oversight council could act as a forum for discussing major issues, making recommendations for corrective adjustments based on results and to act as an arbiter if problems arise.

13.2.3. Risks in the Outsourcing Process

The outsourcing process presented in Figure 13.3 has limitations. Most are related to the potential of risks entering each step in the process. Some examples of risks associated with the steps in the outsourcing process are listed in Table 13.3.

Table 13.3. Examples of Risks Associated with the Steps in the Outsourcing Process

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, Table 1.2, p. 15).

Risks abound in outsourcing projects, as surveys of supply chain executives attest to (see “Global Risks...,” 2011; Global Manufacturing...,” 2011; Carter and Giunipero, 2010; Leach, 2011). Yet outsourcing risk can be viewed as a strategy for eliminating risk. In Figure 13.4, the Da Rold model for risk transference is presented (Gouge, 2003). As illustrated, the more a firm outsources its business activities, the less operational risks (like the risks in managing a supply chain) the firm will have to worry about. However, firms run outsourcing risks just by undertaking a project.

Figure 13.4. Da Rold outsourcing transfer of risk model

Source: Adapted from Gouge (2003, pp. 150–152).

Several outsourcing risks that can lead to project failure are listed in Table 13.4. To deal with some of the risks, firms have embraced outsourcing strategies utilizing one or more types of outsourcing. For example, Badasha (2012) reports that large numbers of European manufacturers are focusing on their supply chain risk challenges by turning to nearshoring as a potential mitigation method (reduces geographic distances in supply chains). Moreover, supply chain risk management programs are viewed as a key issue for manufacturing companies going forward. Risks are particularly prevalent in supply chains that operate internationally or on a global basis.

Table 13.4. Outsourcing Risks and Project Failure

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, Table 2.7, p. 32).

In the final analysis, managing risk is a balancing act between acceptance and avoidance. Ideally, the balance is reflected in the number of business activities a firm insources versus outsources, but to accomplish this, supply chain managers must understand the risks faced in international/global outsourcing.

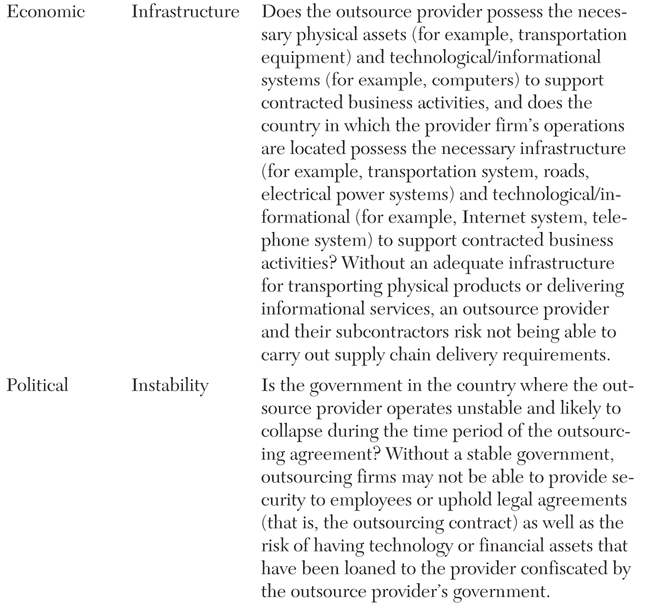

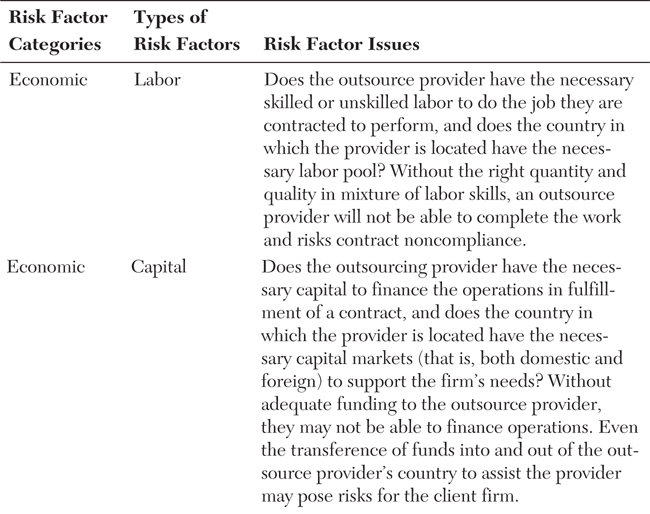

13.2.4. Risks in International/Global Outsourcing

Whether it is recognized or not, outsourcing today, although it can be local, is usually international or even global in scope, dealing with supply chain topics such as procurement, distribution, logistics, inventory, manufacturing, almost anything a supply chain organization can do. Even when a firm believes it is outsourcing to local supply firms, one or two tiers later those suppliers are probably outsourcing to international suppliers. Therefore, grasping the risks that are being undertaken is essential to running a successful long-term outsourcing project. To aid in this task, there is a need to recognize risks that a firm takes when it knowingly goes international with its supply chains. Potential international/global risk taking can be divided into four categories: economic, political, cultural, and demographic risks. Examples of related supply chain international/global outsourcing risk categories are presented in Table 13.5. There are numerous related risks within each of the four categories in Table 13.5. To help conceptualize some of the various risks that exist within the four categories, a framework in Figure 13.5 is presented listing 12 types of risk. Questions related to these 12 types of risk raise are described in Table 13.6. Table 13.6 is not intended to be a definitive listing, but seeks to offer typical questions that may stimulate further consideration of the risk of doing supply chain business with international outsource providers.

Table 13.5. Examples of Related International/Global Risk Factor Categories and Outsourcing Risk in Supply Chain Management

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, Table 3.2, p. 40).

Figure 13.5. Risk factors in international or global business

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, Figure 3.4, p. 41).

Table 13.6. Types of International/Global Risk Factors

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, pp. 41–43).

13.2.5. Combining Outsourcing with Lean Strategy in Supply Chain Management

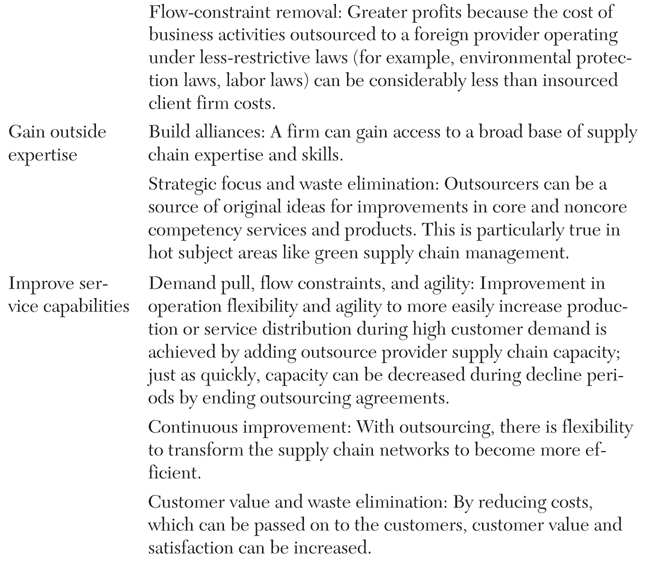

Given the risks and complexity of outsourcing projects, the use of outsourcing has to be driven by the benefits this strategy provides to a client firm. It is clear there exists a substantial body of literature that supports the use of outsourcing as a strategy for many reasons, including the mitigation of risk (Banfield, 1999, p. 228; Slone et al., 2010, p. 136; Schniederjans et al., 2010, pp. 283–302; Zylstra, 2006, pp. 34–35). Few organizations and their supply chain departments use only one strategy to achieve goals. One of the more popular supply chain strategy combinations is a mixture of lean and outsourcing strategies. As previously mentioned, supply chain strategic planning can be greatly enhanced when combinations of supply chain strategies are used to move a firm to world-class performance levels. Table 13.7 provides a list of possible advantages of combining outsourcing with a lean supply chain management strategy. This table can be used to help justify an outsourcing/lean project and provide ideas on areas of possible advantage that an outsourcing project can bring to a client firm.

Table 13.7. Potential Benefits of Outsourcing for Lean Supply Chains

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, Tables 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4, pp. 24–28); Schniederjans et al., 2010, pp. 287–289; Abu-Musa (2011); Boehe, (2010).

13.3. Other Topics in Strategic Planning in Outsourcing

13.3.1. Measuring Outsourcing Services

In the area of outsourcing services, it is important for the client firm to ensure compliance with its goals and directives on the part of the providers. The more attention given to the outsource provider’s behavior in providing services, the more likely that desired results will ensue (Li and Choi, 2009). Li and Choi’s research reported by Wade (2011) suggests employing a rating scale survey divided into two parts where a questions are designed to extract information on both outsourcing outcomes and customer satisfaction. The rating scale is set up on a 1 to 6 scale, where a rating of 1 means the outsource customer completely disagrees with the survey question the way it is stated, and a rating of 6 means they completely agree. For outsourcing outcome questions, Li and Choi suggested they be presented in terms of both negative statements (for example, for the outsourcing services we received, we believe we have paid more than expected) and positive statements (for example, the outsource provider provided timely service). Examples of customer satisfaction survey questions, likewise, should be structured both negatively (for example, our customers were concerned about the services they received) and positively (for example, our customers were pleased the services they received). These combinations help to ensure the rater is thinking about each question and giving an honest response.

Rating and scoring methods to evaluate outsource provider performance are very common methodologies in supply chain management (Schniederjans, 2005, pp. 77–80). When combined with gap analysis (see Chapter 3, “Staffing Supply Chains”), they can provide an ongoing monitoring system of the outcomes and satisfaction of customers with outsource provider performance (Schniederjans, 2005, pp. 84–86).

13.3.2. Outsourcing Benefits and Planning in the Product Life Cycle

As mentioned in several previous chapters, a supply chain life cycle is dependent on a firm’s product life cycles. Operations planning for demand shifts in a product life cycle can be augmented by an outsourcing strategy (Tompkins, 2012; Benkler, 2010). That is, outsourcing activities can be applied to each phase of the product life cycle to enhance efficiency and effectiveness. Some of the potential benefits possible by using outsource providers at various stages in a product life cycle are presented in Table 13.8. Outsourcing at the right time during fluctuations in demand for a product’s life cycle can help support a lean supply chain strategy by stabilizing the broad demand variation inherent in a product’s life cycle by helping to smooth the demand cycle out.

Table 13.8. Potential Outsourcing Roles and Benefits in Supply Chain Product Life Cycle Planning

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005, Tables 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4, pp. 24–28); Schniederjans et al., 2010, pp. 287–289; Abu-Musa (2011); Boehe, (2010).

13.3.3. Global Supply Chain Labor Standards in Outsourcing

With the increasing outsourcing to third parties around the world, many companies have taken an active interest in their conduct related to supply chain labor standards. A survey by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) revealed that 59% of supply chain executives identified bad working conditions as the most significant risk to their supply chains (“Vulnerable to...,” 2008). It was suggested that to mitigate this risk companies need to work in close partnership with suppliers to establish a set of clear expectations of what are acceptable working conditions and what are not. Developing a code of conduct is one way to initiate a risk management project. A research study by Singer (2012) examined the adoption of supplier codes of conduct and supply chain labor policies by major international organizations and governments. The United Nations Global Compact (www.unglobalcompact.org/) was found by Singer (2012) to offer a general framework that focused on labor working conditions and could aid in drafting a supplier code of conduct. In addition, the UN Global Compact offered a useful set of criteria for companies wanting to implement labor condition programs, including social and human rights issues. The UN Global Compact outlined 28 criteria divided into 3 areas of concern that should be considered in negotiations with suppliers when developing codes of conduct (“Supply Chain...,” 2010, p. 22). Useful as a guide for developing a code of supplier conduct, the areas of concern and criteria are presented in Table 13.9.

Table 13.9. Areas of Labor and Social Concern and Code of Conduct Criteria

Source: Adapted from Singer (2012); “Supply Chain...,” (2010).

13.4. What’s Next?

The future trends for the use of outsourcing seem to be mixed, depending on who is doing the forecasting. Freightgate (a logistics software company, www.freightgate.com/) forecast future increasing demand for better collaborative business processes and logistics procurement, coupled with the use of transportation rate management systems that will result in the need for greater execution capabilities, which are currently viewed beyond the knowledge base of most supply chain organizations (“Supply Chain...,” 2012). They believe that response time and budgets of most in-house IT departments will drive a substantial increase in the growth of supply chain outsourcing to better fit the strategic requirements of client firms. The same forecast suggested that trends for increased use of cloud computing (that is, the delivery of computing and storage capacity as a service to end user who access cloud-based applications through a Web browser or mobile technology while other business software and the user’s data are stored on servers at different locations) and mobile applications are creating faster collaborative sharing of information up and down the organization. This faster collaborative sharing is fostering teamwork synergies that improve processes, lessen carbon footprints, ensure adherence to security compliance regulations, reduce noncore costs, accelerate business value, aid in global environmental awareness, improve financial results, and speed up solutions/resolution discovery. Customers expect these outcomes, and so more outsourcing is required to find these capabilities.

Yet others looking to the future believe the outsourcing strategy is not necessarily as beneficial as it has been and therefore will decline. Albert (2011) reported on the KPMG’s 3Q11 Sourcing Advisory Pulse (www.kpmg.com/) survey that disappointment with underachieving outsourcing efforts, changing economics, and a desire for greater control over strategic processes and sensitive data were reasons that firms struggle to make outsourcing work. In addition, the survey suggested client firms would continue to face challenges managing outsourcing transition processes and that their efforts would be hampered by a lack of skilled resources and by inadequate planning and procedures. This means failure in outsourcing transition efforts in terms of not being completed on time, within budget, or not achieving the required functionality. To compensate for the failures and to try to salvage some of the benefits of outsourcing, one trend noticed in the survey was that interest and adoption levels for shared services increased, due in part to disappointing outsourcing efforts and a wish to avoid overly aggressive outsourcing. The report stated that buyers had moderate success in achieving goals sought from shared service efforts, with cost savings being the most often cited goal (Albert, 2011).

Also, according to Leach (2011) and Beatty (2012), some of the most attractive countries (for example, India, China) are expected to have double-digit inflation going into the future. Given the main reason for outsourcing is low manufacturing and labor costs, inflation and local wage cost increases may end the growth and even mark a potential decline in offshoring. Although the current inflation rates and rising costs are yet to change the practice of outsourcing drastically, the next five years might see the disappearance of the term offshoring. In addition, it is clear that the business environment offered in foreign markets is altering. Global business services companies have become so effective in investing in technology that they are providing commercial-grade services. As a result, the old attitude that outsourcing overseas will cut costs but that a firm must accept poor quality has now changed. Firms are seeing improvement in quality from these same sources.

Most outsourcing decisions have been based on cost minimization, and many have failed. As the previously mentioned surveys reveal, the goal of cost minimization using the outsourcing strategy may not be as successful going forward. Regardless of the upward or downward trend of outsourcing in supply chain management, one constant should be followed to avoid the failure of projects. Moser (2012) suggests a new trend in evaluating outsourcing. Any outsourcing venture should be undertaken only with more extensive and inclusive analysis, bringing into consideration criteria that was until now excluded from consideration. Moser (2012) recommends a total cost of ownership (TCO) (Chapter 12, “Lean and Other Cost Reduction Strategies in Supply Chain Management”) approach that includes the following:

• Costs of goods sold or landed costs, including price, packaging, duty, and planned freight costs

• Other costs, including factors affecting them, such as carrying costs for in-transit products, inventory onsite, prototyping, end-of-life or obsolescence, and travel costs

• Possible risk-related costs, including rework, quality, product liability, intellectual property, opportunity costs, brand impact, economic stability, governmental political stability, and recession

• Strategic costs, including impact on innovation, product differentiation, and mass customization

• Environmental costs, including those involved in going green

Moser suggests that by using inclusive analysis, which most firms in the past have not undertaken, not only will outsourcing failure rates be reduced but firms might also realize the TCO of outsourcing a current or future project is not in the best interest of the firm. What this means is that some firms currently involved in outsourcing might need to undertake a reshoring initiative to insource their supply chain and production activities.