11. Risk Management

11.1.1 What Is Risk Management?

11.1.2 Types of Supply Chain Risk

11.2 A Risk Management Process

11.3 Strategies and Tactics for Mitigating Risk

11.3.1 Preparedness and Resilience Strategies and Tactics

11.3.2 Supplier-Related Strategies and Tactics

11.4 Other Topics in Risk Management

11.4.1 Innovating Risk Management

11.4.2 Risk Management Tool: Traceability

11.4.3 Disrupter Stress Test to Estimate Risk of Future Catastrophic Events

Terms

Business-continuity planning (BCP)

Disrupter analysis stress test

Supply chain incident management

11.1. Prerequisite Material

11.1.1. What Is Risk Management?

Risk management is a process of identifying potential negative events, assessing their probability of occurrence, reducing the probability of their occurrence, or seeking to avoid them completely, and preparing contingency plans to mitigate the consequences if they happen (Blanchard, 2007, pp. 241–245). In every stage of the product life cycle, risks are taken as customer demand changes. Risk needs to be managed, reduced, or eliminated to prevent the product life cycle from being shortened. Risk mitigation means lessening or eliminating risk or its impact. In general, there are two types of risk: operational risk and disruption risk (Knemeyer et al., 2009; Wakolbinger and Cruz, 2011). Operational risk involves a supply-demand lack of coordination resulting from inadequate or failed processes, people, or systems (Bhattacharyya et al., 2010). Examples of operational risk include the possibilities of poor quality or unsuccessful delivery. Disruption risk can be caused by human or natural disasters such as terrorist attacks, strikes, earthquakes, and floods. Leach (2011) reports that 51% of the 559 companies in a global survey said the most common disruptions in their supply chains were caused by adverse weather conditions, while 41% reported information technology outages were the next major source of disruptions. Christopher (2011, p. 194) and Flynn (2008, pp. 112–120) suggest there are several sources of disruption risk (see Table 11.1).

Table 11.1. Sources of Potential Supply Chain Disruption Risk

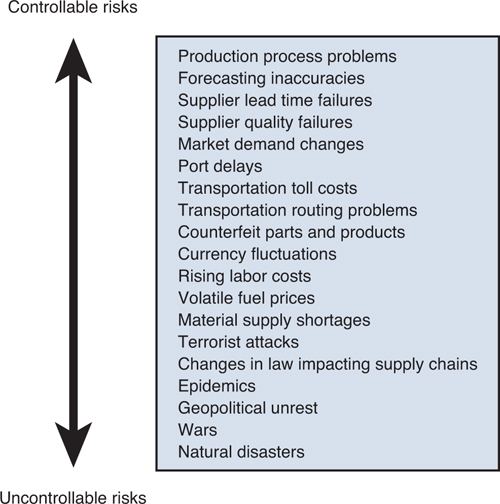

Risks can be categorized into three levels: controllable, somewhat controllable, and uncontrollable (Byrne, 2007). Using this framework, disruption risk is more likely to be uncontrollable, whereas operational risk is relatively controllable. A survey by Byrne (2007) reported that supply chain managers believed the predominant and most daunting risks to supply chains were controllable risks associated with performance of supply chain partners. Figure 11.1 lists a selection of supply chain risks and provides a related continuum of controllability.

Figure 11.1. Types and controllability of supply chain risks

Source: Adapted from Simchi-Levi (2010), Figure 5.1, p. 74.

11.1.2. Types of Supply Chain Risk

One type of supply chain risk is supplier risk, which focuses on event outcomes that are detrimental to the sourcing plans in a supply chain for a purchasing organization (Carter and Giunipero, 2010). These events usually fall into either operational or disruption risk suggested earlier, except if the event relates more narrowly to suppliers: (1) supplier financial distress, and (2) supplier operational failure. Other supplier operational risks that impact the purchasing organization can include factors like those listed in Table 11.2. There are as many types of supply chain risks as there are things that could go wrong in a business. In formalizing a risk management program Fawcett et al. (2007, pp. 105–108) suggests a commodity manager (that is, someone responsible for a particular commodity or grouping of products) should take ownership for the risk management process and oversee risk assessment. One risk assessment method is the risk scorecard (that is, a survey listing risk criteria that can be scored to determine an overall risk rating). Results are later reported to appropriate managers to develop risk mitigation plans.

Table 11.2. Types of Supplier Operational Risk Factors Impacting Purchasing Organization

11.2. A Risk Management Process

The risk management process that is presented here is viewed as a project, but in reality, it should be seen as an ongoing program. Risk creeps into every task that a business undertakes, so supply chain managers should have in place a supply chain system or group to continually scan for risks in their operations or environment. In addition, supply chain managers should have in place multiple means of risk detection within the organizational structure. These multiple means should include automated technology systems, processes, policies, procedures, and personnel within and external to the organization to ensure potential risk is identified and reported quickly.

Many steps can be incorporated into a risk management process. The type of organization, industry, and products can all alter the steps needed during the risk management process. Christopher (2011, pp. 198–206) and Flynn (2008, pp. 112–127) suggested the ordered steps listed here as a framework for a risk management process (see Figure 11.2):

Figure 11.2. Steps in the risk management process

Source: Adapted from Flynn (2008, pp. 112–127).

1. Establish a risk management team: A risk management team is an internal and formal cross-functional team made up of individuals who are connected to the domain of interest and are assembled to undertake and manage the risk management process. In highly supplier dependent or strategic supplier situations, a cross-organizational team that includes members from the key supplier should also be included. While engineers and supply chain managers related to the risk domain of concern will be members of the team, other specialists can be included, particularly those that bring quantitative skills useful for assessing or estimating risk probabilities. Team members must be skilled in identifying potential risk elements, estimating impacts on the organization, developing strategies of mitigation, and suggesting strategy implementation steps. Members may later be added or released when dealing with new or differing issues of risk that are uncovered or become obvious during the latter steps of the risk management process. Also, executive management must decide how much control over the risk situation the team will have. Risks that come from external sources may not be eligible for consideration by a team that is chiefly comprised of internal organization members. Therefore, executive management might reserve the right to control aspects of the team’s decision-making process.

2. Identify the source of risk: The risk management team must identify the sources of risk. The sources of risk can be general in nature like those listed in Table 11.1 that impact broad areas of disruption in supply chain operations. Alternatively, the sources of risk may be focused narrowly on a single area in supply chain management like risks connected with one supplier (see Table 11.2). Using similar reasoning to that of the fishbone diagram (see Chapter 4, “Managing Supply Chains”), which seeks to trace sources of undesirable quality variations, identifying the sources of risk may involve starting with an observed disruption or change in the environment, then tracing it back to the factors that contribute to the cause of the disruption or changes.

3. Estimate the probability of risk occurrence: Assessing the exact probability in any risk situation is almost impossible, but generating a likelihood of a particular event happening (for example, a key supplier going out of business) is what this step concerns. Rating systems that rank or reflect the riskiness of a particular event are common in the literature. Rating the occurrence of an event as (1) very high, (2) high, (3) moderate, (4) low, (5) very low, or (6) unlikely is the subjective-judgment evaluation that is expected. The internal organizational experience of supply chain managers, executives, engineers, knowledgeable staffers and external industry experts, consultants, and lawyers may all be a source, for this estimation process.

4. Estimate impact of risk on supply chain and develop a risk profile: This step requires a judgmentally determined estimation of how risk tolerant an organization is to any likely risk event occurring. A risk profile defines an organization’s risk-aversion level. At this step of the risk management process, the analysis may be complete if a firm is highly risk tolerant and not averse to accepting a particular risk situation. If the risk event is judged to exceed a firm’s tolerance and it is averse to accepting the risk situation, however, the potential impact of the risk event must be determined. This can involve investigating best and worst case scenarios regarding the impact of the risk to the organization. This would also involve looking at the potential impact in terms of various stakeholders (for example, supply chain, other departments and personnel) and estimating the impact on each. This assessment may also lead to the end of the risk management process if the amount of risk is so great that management deems the project too risky an undertaking. A useful scale for measuring impact might be a rating scale (for example, (1) marginal impact, (2) significant impact, (3) critically damaging impact, and (4) catastrophic impact). These assessments are also judgmentally estimated based on executive experience, and in some cases, external expert opinion. The outcome of this step for organizational avoidance of risks is a clearly assessed impact of risks that the firm may be facing and a rating, ranking, or prioritization to delineate an ordering of the importance of each so that they can be dealt with efficiently.

5. Develop risk management strategies: Given that in the previous steps risks were identified, impacts assessed, and risks prioritized according to importance, management strategies can now be developed to deal with each. According to Flynn (2008, pp. 123–124), risk management strategies typically fall into the four categories listed in Table 11.3. Which strategy to accept depends largely on the tolerance of the firm for taking risks. (The next section deals with strategy and tactics in risk mitigation.)

Table 11.3. Types of Risk Management Strategies

6. Allocate resources: In this step, the allocation of adequate personnel, technology, and capital resources must be determined and affixed to each strategy. It also involves estimating the cost of implementing risk management strategies and allocating resources to implement them. One way to rationalize investment in these strategies is to reexamine the assessed impact to the organization of the risk and to measure those costs relative to the costs of the strategies. Although it is difficult to accurately estimate potential cost savings of mitigating a risk versus the actual cost of the strategy, it is often true that the cost of accepting a risky situation far exceeds that of lessening it.

7. Implement strategy: In this step, tactics for the implementation of the risk management strategies are developed and put into place. The implementation of any strategy should begin with alignment to the organization-wide strategies. Once done, the implementation of multiple strategies to deal with risk situations can proceed. This step also involves the execution of allocated resources (from step 6).

8. Feedback results and revise if needed: The risk management team is usually held responsible for ensuring strategies and resource allocations are effectively implemented and desired results are achieved. Sufficient time after the implementation of the strategies should be allocated to the team to assess the success (or lack thereof) of the risk management project. If less-than-desirable results are observed during this evaluation period, changes might be made to correct or realign the strategies to achieve better results. Regardless, the end report of the risk management team is expected to be available to areas in the organization that are impacted by the risk management efforts.

11.3. Strategies and Tactics for Mitigating Risk

Risk taking is inherent in supply chain management. Given the complexity of most supply chains, it is difficult to conceive any supply chain not having risk. Supply chain management and risk taking are synonymous terms for most managers, but that does not mean risk should be excused or ignored. The best defense to reducing risk is a good offense of risk mitigation. Risks should be reduced or eliminated wherever they exist, consistent with the cost viability of reduction or elimination. To that end, a variety of risk mitigation strategies and tactics are evident in the literature.

11.3.1. Preparedness and Resilience Strategies and Tactics

The best strategy for mitigating risk is to build preparedness and resilience into supply chains. A preparedness strategy involves anticipating and preparing for worst case scenarios in supply chain operational disruptions or environmental catastrophes to mitigate risks. Global companies with clear visibility of supplier activities are better able to leverage that visibility and act quickly when a detrimental event occurs. With information, they can make an informed decision to divert to qualified alternative suppliers if necessary, ensuring correct commodity pricing and assessing the effects of currency changes on buying decisions. Companies can strategically utilize information technology to optimize supplier activities and avoid disasters. According to Correll (2011), one preparative tactic to avoid pricing disasters is to use Internet access to track negotiated commodity pricing, commodity index, and final delivery rates to avoid overpayments. Purchasing organizations can use this tactic to avoid supplier-based billing errors and ensure that competitive suppliers in different locations are price reliable in the event a purchasing organization needs to make a last-minute supplier change. Another preparative tactic based on the use of communication technology is to disperse out vendors over a large geographic area to avoid the impact of a natural disaster that might adversely affect production or disrupt a transportation network of a supply chain at any given time. Having a set of preapproved alternative suppliers in multiple geographic locations creates a solid foundation of preparedness in dealing with natural supply chain disruptions. Currency fluctuations can also be costly and potentially might negate expected cost savings of going global. Although no company can accurately predict the risk in a foreign exchange rate that changes over the long term, a purchasing firm can prepare and insulate itself against major impacts by ensuring up-to-date information on the latest currency valuations are available to decision makers regarding supplier pricing.

Sirkin (2011) also suggests a strategy of preparedness to deal with supply chain disruptions that includes the following tactics:

• Diversify supply bases: Identify and recruit suppliers in different locations, including some close to home to avoid regional problems (like war) from risking a loss of key suppliers.

• Secure supplies: When a disaster happens, lock up needed supplies with contracts to avoid shortage risks.

• Flexible supply chains: Create supply chain networks that have the flexibility (see Chapter 9, “Building an Agile and Flexible Supply Chain”) to adjust to sudden changes in demand and supply chain needs, in order to avoid risks associated with meeting market or environmental changes.

• Produce locally: Utilize local suppliers to augment existing distant suppliers to avoid the risk of not meeting shifts in demand and avoid price increases.

• Alter costs: Purchasing firms should lower fixed costs and seek to exchange them for variable ones that fluctuate with the market to avoid the risk of overcapitalization and the associated financial risks. One tactic is to outsource (see Chapter 13, “Strategic Planning in Outsourcing”) to exchange fixed costs, through surrender of capital investments to an outsource provider, for variable costs of an outsourcing contract.

Risk management is not static but dynamic and needs continual consideration of new and varied situations. There is so much change in the types and situations of risk that viewing internal capabilities to resist and deal with future risk has become an important part of risk management. Resilience implies a capacity to return to a normal state quickly after being disturbed. A resilient supply chain is one that can handle negative impacts from risky situations without having its life cycle come to an end. Knemeyer et al. (2009) and Siegfried (2012) suggest firms become proactively resilient by embedding supply chains end to end with resiliency in products, supply chain, planning, and managing incidents. A tactic for a resilient supply chain strategy is product resiliency. Product resiliency involves working with product development staff during the introduction of new products to identify areas of risk in the early product development sourcing phases. Knowing the product risk weaknesses allows for risk reduction efforts prior to the product’s introduction and mitigates risk factors. Another tactic is supply chain resiliency. It involves the identification and mitigation of risk areas in the supply chain that might prevent quick recovery from major disruptions within a specific time period. Working with supply chain organizations and consultants to perform this risk analysis and mitigation is suggested by Siegfried (2012).

Another tactic is through use of Web-based business-continuity planning (BCP). BCP is an information tool that compiles dozens of resiliency data metrics for all critical supply chain partners and keeps those metrics up-to-date. The information, which includes emergency contacts, alternative power providers, and estimated time to recover from a disaster, can be used for a supply chain incident management process. Supply chain incident management takes the information from a BCP and uses an alert service to help monitor worldwide environmental events (for example, disruptions of transportation lanes) that might have disruptive impact on a purchasing organization’s supply chain. Siegfried (2012) reported that firms like Cisco Systems utilize an executive dashboard to provide visibility of the supply chain incident management process to report incidents, as well as to develop a crisis playbook detailing processes for reacting to disasters and mitigating different types of risk. Cisco actually developed a resiliency scorecard that includes four categories of resiliency for manufacturing, suppliers, components, and test equipment (O’Connor, 2008). Still, another resiliency tactic is building redundancy in to supply chain systems (Sheffi, 2005, pp. 270–278). While opportunities to reduce resources and capacity in supply chains are important for cost reduction goals, there should be a balance to avoid distressing the entire supply chain, which could cause disruptions. The amount of excess should be in direct proportion to the variability in the supply chain in much the same way safety stocks are computed to determine a desired service level.

11.3.2. Supplier-Related Strategies and Tactics

Risks related to suppliers can lead to a critical or even catastrophic situation impacting the purchasing firm. Some of the strategies used by purchasing firms that have singularly focused on cost reduction have also led to an increase in risk, according to Carter and Giunipero (2010, p. 11). Strategies that should be reconsidered in light of the desire to reduce supply chain risks include the following:

• Reducing the number of suppliers or having single-source suppliers, risking costly dependency

• Reducing inventory, risking shortages

• A high concentration of business with a few suppliers or customers, risking dependency on those partners

• Dependancy on a specific type of infrastructure, risking bottlenecks in transportation systems or facility loading needs

• Increasing the use of outsourcing, risking dependency on suppliers

• Use of low-cost suppliers in developing countries, risking dependency on sources located in countries that may be politically unstable

• Long lead times, risking timely deliveries and stockouts

Risk mitigation tactics suggested by Carter and Giunipero (2010, p. 11) to deal with a suppliers who may have financial or operational distress include the following:

• Investing or buying the supplier outright

• Giving the purchaser’s business to another supplier

• Paying early to help the supplier with cash flow

• Accepting early delivery to advance payments to the supplier more quickly

• Visiting the supplier to see if long-term help can be provided

• Seeking collaboration from other suppliers to help the disstressed supplier

• Making direct loans with low interest to financially weak suppliers

• Increasing business with the supplier in the short-term to improve cash flow

11.3.3. Managing Global Risks

Experienced supply chain managers know that the impact of a global supply chain adds an additional layer of risk complexity to an already risky environment. The result is an exponential increase in risk that is required in today’s supply chain and yet should require reexamination of the amount of global involvement that a firm should undertake. The literature suggests a variety of different strategies to deal with global risk taking, including the following (Kogut, 1985; Colicchia et al., 2011):

• Hedging: Under this strategy, a supply chain is designed that any loss in one part is offset by gains in another. In global operations, where production facilities are located in different countries, the individual currencies of each country can hedge against currency fluctuations. Where one country’s currency is lowered, another in the supply chain network is increased. This is the same strategy used to reduce risks by diversifying investments in a variety of financial instruments.

• Speculation: Under this strategy, a supply chain is focused chiefly on one goal that provides substantial benefit to the firm. In the past, the primary reason why most firms went global was to seek lower product or operational costs. Speculating on a single unique opportunity, a global organization may have lower production costs in low-wage countries, resulting in a significant competitive advantage through lowering prices to the customers. This strategy can work well, but as time goes on, conditions can change to minimize the primary cost reduction reason. As wage levels increase or inflation impacts an economy, the desire to maintain a goal such as low labor costs might require a continuous process of moving from one country to another to chase lower wage levels globally.

• Flexibility: Building a supply chain based on this strategy would seek to have flexibility in partner quantity, quality, and capabilities. One of the virtues of global operations is the ability to have a much larger supply chain base from which to select partners. Having more suppliers, manufacturers, and distribution operations allow for greater flexibility in dealing with supply chain disruptions in any area of the world. Having redundant production resources and alternative supply chains permits a hedge against many risk factors that keep supply chains from performing well. This strategy allows for quick changes and rerouting when risky environmental changes (for example, wars, weather) take place in one particular region.

Global strategies to overcome risk are almost infinite. Most firms use a combination of the strategies mentioned here to accomplish global goals.

Christopher (2011, p. 194) has hypothesized a function that defines supply chain risk as follows:

Supply chain risk = Probability of a disruption x Impact

Some of the strategies and tactics of risk mitigation in this section can reduce the probability of a disruption of supply chain operations or reduce the impact of the risk event on the purchasing organization. In doing so, the risk to a supply chain can be reduced. That is the purpose of risk management.

11.4. Other Topics in Risk Management

11.4.1. Innovating Risk Management

According to Leong (2012), much of traditional risk management is a backward-looking process at past risk situations, but should be made forward looking to anticipate risks. Leong (2012) reported that four components are needed to innovate risk management programs to a forward looking mode:

• Develop a supplier-based database system: Risk situations are constantly occurring. Under this system, supply chain professionals, working for or in a purchasing organization, continuously feed information about potential or real risk factors they observe in their job situation environment. These observations form a database of real-time information on risk situations that may be developing and that therefore need more attention and focus. This information may be gleaned from public sources such as news releases, annual reports (for example, supplier financial reports), and analyst reports (for example, Harvard Business Review blogs). Observations might include changes in economic conditions, organization leadership, industry, and technology. They may also include initiatives and new strategies from competitors, as well as legal or government action against supply partners.

• Apply business analytics: Taking raw data from the database, heuristics (that is, logic based rules to guide searches), and other search methodologies, artificial intelligence (AI) and data-mining software (that is, a software driven process that seeks discovery of patterns or trends in databases and transforms them into human understandable structures for further use) can be applied to find trends or behavior revealing risk leading situations that are yet to be formally recognized (“Intelligence Agent,” 2012). Combined knowledge of competitors and industry behavior, executive experience, and intuitive judgment can also be applied to analyze data. For example, the loss of several suppliers in a purchasing organization’s network may reveal a competitive risk factor such as a competitor’s moving into markets, which the purchaser previously dominated, and recruiting former suppliers. Although this situation might indicate some other cause and effect, identifying risk possibilities such as competitive actions is worthy of further consideration because it may reveal actual risk-related factors leading to supplier loss.

• Frequent risk assessments: To stay current and have what Leong (2012) refers to as real-time risk assessments requires updates to the database of every significant transaction (for example, a supplier bid transaction). This could require daily or even more frequent reporting efforts. This allows the purchasing organization to keep timely track of risk ideas, risky behavior, and risk assessments and to note changes that might indicate an alteration of risk trends.

• Simplifying the process: The variety of information inputs from a wide and varied set of sources throughout a supply chain network is channeled into useful and timely decision-making information. Under this system, it becomes easier to identify the variety of risks that actually impact a purchasing firm and its supply chain network. Therefore, the opportunity to reduce and simplify risk data collection makes the process easier and more efficient. In turn, the amount of time available to focus on key risk factors is increased and better controlled.

The goal of this risk assessment system is to increase knowledge of risk for a particular purchasing firm and to locate where disruptions may occur using a broad and diverse set of inputs. By increasing awareness, this system allows firms to respond more quickly to risk situations and minimize disruptive impacts on the supply chain network.

11.4.2. Risk Management Tool: Traceability

Sometimes, a product problem (for example, a defective product that may cause a safety issue) surfaces and the firm responsible has to undertake corrective action. The longer a firm allows a known product problem to continue, the greater the risks for impact costs (for example, legal action against the firm). Just finding the source of a problem for a large organization with a global supply chain network is a challenge. The longer a problem remains hidden and is not remedied, the greater the associated costs and other risks to the supply chain organization. Given the complexity of products, their sources of manufacturing, and the length of their supply chains, it can be very difficult to determine where a problem originates. Conversely, the faster a problem’s origin is identified, the less risk and related costs will be incurred.

Siegfried (2011) suggests that traceability (that is, the ability to trace down a problem or issue) is an ideal risk management tool. Being able to trace a product back from its origin can improve supply chain management by facilitating the identification of safety and quality issues. How much traceability is required depends on what an organization wants to achieve and how much it is willing to pay. A product, the component parts, and the location of the materials used for the component parts are all traceable if the firm is willing to expend the effort.

Siegfried (2011) suggests three characteristics are mandatory in the design of traceability systems: (1) breadth (that is, the amount of information that is to be kept on each product or component), (2) depth (that is, the depth of information that traces backward or forward in time for the product or component, which can be updated as the item moves through the supply chain), and (3) precision (that is, the degree of assurance that the tracing system has the ability to pinpoint a particular item’s movement or characteristics).

Technologies like bar codes that are read by scanners and connect to the storage of information on mainframe computer systems can help locate and detail product characteristics. Global positioning systems (GPS) can be used to determine location in transit when timely physical location information is needed. Radio frequency identification (RFID) technologies that permit electronic and distant inventory monitoring can also support a traceability program. Such technologies can make the program easier and more affordable.

Traceability as a strategy for supply chain operational success is becoming a reality. Governmental requirements for product safety and the desire by consumers to trace products as they are logistically moved through a supply chain, are some of the competitive reasons for adopting/enhancing this supply chain capability.

11.4.3. Disrupter Stress Test to Estimate Risk of Future Catastrophic Events

Large firms can handle risk management efforts by allocating one whole department to risk. Referred to as enterprise risk management (ERM) departments (Le Merle, 2011), their purpose is to identify potential business disruptions, determine the most likely effects, and develop risk mitigation plans, while also taking preventive actions to reduce risk exposure. ERM departments focus on more frequently impacting risk issues (for example, failure to comply with government regulations). They tend not to focus on black swans (that is, an infrequent, but extremely impacting disaster that can be related to an environmental, economic, political, societal, or technological cause). A black swan can occur anytime, anywhere and is highly impossible to predict, which explains why most ERM departments are not necessarily prepared to handle these kinds of risk events.

To deal with a black swan event, Le Merle (2011) suggests the use of a disrupter analysis stress test. These stress tests should be administered periodically by a risk management team that would work with the ERM department. While the stress test is not meant to be a continuous effort (that is, they should be considered a project activity), it should be considered as an occasional tune-up effort to anticipate and suggest strategies for dealing with the supply chain ramifications of a major disaster. While ERM departments or a special risk management team would seemingly undertake this task, some organizations may select to have an external third-party conduct the analysis for a host of reasons including external objectivity.

A disrupter analysis stress test can consist of the following four steps (Le Merle, 2011):

1. Map the enterprise to define locations of potential catastrophic risk: This step involves determining a firm’s geographic footprint in terms of operations and supply chain partners. This mapping includes multiple-tiered operations: first-, second-, and third-tier suppliers. This also includes the external industry structure and competitive dynamics in the market the firm faces. Given such information, a map of sources and concentrations of revenue, profit, and capital of the firm is also needed to understand other areas of potential risk and how everything is interrelated.

2. Create a list of black swan events: A list of potential disrupting events should include any that may be related to the organization in the context of environmental, economic, political, societal, or technological impacts. This is expected to be a long list that may be categorized in different ways, such as by type of risk. The categorization helps reduce the number of types of risks, making it more manageable.

3. Explore “what if” scenarios: Determine the relative impact and consequences to the organization of a given catastrophe as it relates to each of the listed black swan events (from step 2) and its relationship to the organization’s mapped concentrations of potential risk (from step 1). The idea is to expand and look for as many possible risk factors and relationships, while also assessing the potential magnitude of what the catastrophes might cause. Matching up concentrations of risk with the potential impact of the catastrophe helps identify how the current structure of the firm (that is, from the mapping effort in step 1) may be a factor contributing to the potential magnitude of the impact.

4. Implement contingency plans: Develop risk mitigation options for each risk situation from step 3. Develop options that address multiple risks and prioritize them by magnitude of risk exposure, expense, and ease of implementation. Coming up with these contingency plans can be a brainstorming activity for the risk management team, the ERM department, or for consultants could utilize with unique experience in risk contingency planning, which an organization hires to augment internal staff knowledge.

The idea in using this disrupter analysis stress test is to prepare an organization in advance with standby emergency plans that could be quickly implemented to minimize future risks and their consequences during black swan events.

11.5. What’s Next?

Based on the World Economic Forum (www.weforum.org) research report, the trend for watchfulness regarding the topic of risk in global supply chains tops the list of major concerns of supply chain managers (“Outlook on...,” 2012). Both businesses and government agree there is a strong need for supply chain security that mitigates risk. Despite the desire for less-risky supply chains, the forecast for the near future appears to be risk endowed. As shown in Table 11.4, there are not only a great many risk factors (this list is incomplete from those originally surveyed by the World Economic Forum [“Global Risks...,” 2011] and other sources) (Simchi-Levi, 2010), but each has a likely to high probability of occurrence. Unfortunately, most of these risks are estimated to be high and will negatively impact global supply chains.

Table 11.4. Global Risk Categories, Examples, and Estimated Probable Occurrences in 2012

Source: Adapted from Global Risks 2011(2011); Outlook on Logistics & Supply Chain Industry 2012 (2012); Simchi-Levi (2010, pp. 73–77).

What can be done to mitigate the global risks that are looming is to take proactive measures that anticipate and strengthen the resilience of supply chains to handle eventual impacts. Similar to previous strategies offered in this chapter, the World Economic Forum research suggests supply chain managers maintain an oversight to capture risk information, synthesize, and analyze it to the point where useful action-oriented information can be shared rapidly to formulate anticipatory decision responses (“Outlook on...,” 2012). Moreover, this research recommends building agility, flexibility, and adaptability in to the supply chain (see Chapter 9) to make it more resilient and better able to handle risky situations and their impacts.