5. Social, Ethical, and Legal Considerations

5.2 Principles and Standards of Ethical Supply Management Conduct

5.3 Principles of Social Responsibility

5.4 Measuring Social Responsibility Performance

5.5 Other Social, Ethical and Legal Topics

5.5.1 Legislation: California Transparency in Supply Chains Act

5.5.2 Alternatives to Litigation

Terms

Adjudication

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR)

Arbitration

Business in the community corporate responsibility index

Business law

California Transparency in Supply Chains Act

Commercial law

Common law

Corporate law

Corporate social responsibility (CSR)

CRO Magazine Best Corporate Citizens

ECPI ethical index

Fair factories clearinghouse (FFC)

Fair factories clearinghouse (FFC) database

FTSE4Good

Global environmental management initiative (GEMI)

Information and communications technology (ICT) supplier self-assessment

Mediation

Mediator

Public company accounting oversight board (PCAOB)

Sarbanes-Oxley Act

Social Accountability International (SAI)

Social accountability international (SAI) SA8 tool

Social responsibility maturity matrix

Sustainability and social responsibility for supply management: assessment

Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) Act

World’s Most Ethical Company publication

5.1. Prerequisite Material

This section is chiefly to acquaint less-experienced students of supply chain management with basic and elemental content and terminology. Experienced supply chain executives and managers might be tempted to skip this section in chapters where it is included, but they might instead want to use it as a review of basic concepts and terminology.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is defined by Svendsen et al. (2001) as “a company’s positive impact on society and the environment, through its operations, products, or services and through its interaction with key stakeholders such as employees, customers, investors, communities, and suppliers.” Many business organizations believe the government should regulate the environmental performance of organizations; others prefer to have the flexibility of voluntary standards. The increasing customer demand for companies to provide better environmental safeguards has pressured suppliers, manufacturers, and distributors to be responsible for environmental actions. In response, suppliers and manufacturers have attempted to produce more environmentally friendly products, establish recycling network systems, and minimize emissions to improve their reputations among customers and consumers.

What backs up CSR programs is a dual balancing of a firm’s desire to behave ethically and what must be done because of legal dictates. The individuals who make up a business organization know that behaving ethically attracts customers and avoids legal problems related to issues like pollution and environmental waste. However, a CSR program can be very costly, and customers are not attracted to excessively high product prices, which a CSR program can cause. The balance between a firm’s ethical conduct standards and a firm’s desire not to incur substantial CSR costs is sometimes determined by government regulation. Unfortunately, government regulations often represent a low bar in constraining unethical business operations, but they are a factor and have become an increasingly powerful influence on a corporation’s attitudinal change toward higher ethical conduct. The best firms exceed government regulations in order to not only avoid litigation but also to demonstrate to stakeholders that they do stand for high ethical values in the conduct of business operations.

Table 5.1 describes some of the laws and acts that have been passed that relate to supply chain management concerns. These constitute basic foundation law knowledge for all supply chain managers. On a more narrow focus, the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) suggests that the primary areas of legal concern that govern ethical issues applicable to supply chain management include the following (Carter and Choi, 2008, p. 266):

• Defamation, also called vilification, slander (for transitory statements), or libel (for written, broadcast, or published words), is the communication of a statement that makes a claim to be factual and that may give any person or thing (for example, products, brand name, company) a negative image (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Defamation). For example, one supplier may falsely suggest to a buyer that a competitor supplier cannot be trusted to deliver products on time, when in fact there is no evidence to support that assertion.

• Disparagement is to falsely suggest a connection with persons, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, bringing them into contempt or disrepute (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disparagement). For example, one supplier may make false statements about the brand quality of another supplier’s product.

• Bribery is a form of corruption, an act implying money or gift giving to influence the recipient’s conduct. Bribery constitutes a crime if the offering, giving, receiving, or soliciting of any item of value is offered to unduly influence the actions of an official or other person in charge of a legal duty (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bribery). For example, a manufacturer might offer a kickback to a procurement agent if the agent will do business exclusively with the firm to the exclusion of other competitors.

Table 5.1. General Legislative Laws and Acts That Can Impact Supply Chain Operations

Source: Adapted from Carter and Choi (2008), pp. 278–282.

Suppliers act as agents for their respective buyer or supply chain customers. The law of agency in commercial law deals with relationships whereby a person (the agent) is authorized to act on behalf of another (the principal). The principal authorizes the agent to work on the principal’s behalf, and the agent is required to negotiate on behalf of the principal (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Law_of_agency). The law of agency is the legal basis for rulings concerning bribery in procurement.

5.2. Principles and Standards of Ethical Supply Management Conduct

“We operate with the highest standards of integrity and ethics.”

—Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) statement of values, from the CSCMP Web site: http://cscmp.org/aboutcscmp/inside/mission-goals.asp

Two ethics-oriented supply chain management professional organizations are the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) and the Institute of Supply Management (ISM). These organizations provide training on ethical concepts, principles, and conduct. Their certifications for supply chain managers also include a requirement of knowledge of social responsibility and ethical standards.

The ISM bases its ethical conduct behavior advocacy around three principles: integrity in decision making and actions, the need for supply chain employees to value employers, and loyalty to the supply chain profession (see www.ism.ws/tools/content.cfm?ItemNumber=4740&navItemNumber=15959). Based on these principles, ISM has established a set of standards for supply management conduct (see Table 5.2). These standards are excellent guidelines for supply chain organizations to adopt and use to develop an applicable set of standards. In addition, ISM offers training courses (www.ism-knowledgecenter.ws/KC/courses.cfm), research (www.ism.ws/files/SR/capsArticle_PurchasingsContribution.pdf), publications (www.ism.ws/pubs/journalscm/index.cfm?navItemNumber=5474) and educational materials (Carter and Choi, 2008), which are available to encourage and empower the development of an ethics program.

Table 5.2. Adapted ISM Standards for Supply Management Conduct

Source: Adapted from ISM website www.ism.ws/tools/content.cfm?ItemNumber=4740&navItemNumber=15959. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

5.3. Principles of Social Responsibility

ISM believes supply professionals are uniquely positioned to impact supply chains and encourage promotion of social responsibility through participation on supply chain committees, boards, and panels of governmental and nongovernmental organizations. In their management role, supply chain employees can help develop and implement social responsibility ideals and principles by inclusion and consideration of appropriate business strategies, policies and procedures.

ISM combines the principles of sustainability (see Chapter 6, “Sustainable Supply Chains”) with those of social responsibility (www.ism.ws/SR/content.cfm?ItemNumber=18497&navItemNumber=18499). Table 5.3 describes these principles of social responsibility. They can serve as a foundation for individual firms to map out their own unique set of social responsibility principles.

Table 5.3. ISM Principles of Social Responsibility

Source: Adapted from the ISM Web site: www.ism.ws/SR/content.cfm?ItemNumber=18497&navItemNumber=18499. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

5.4. Measuring Social Responsibility Performance

It is one thing to establish a set of principles for social responsibility and quite another to ensure they are being implemented. Some companies use outside sources of information to determine whether social responsibility programs are working. For example, CRO Magazine (www.thecro.com/content/cr-announces-100-best-corporate-citizens-list) annually lists, in a Best Corporate Citizens list, companies that provide good corporate citizenship. It is viewed as an honor and recognition if a firm has achieved some social responsibility status in its industry and to be listed in this publication. The Ethisphere Institute (an organization dedicated to the advancement of best practices in ethics, corporate social responsibility, and anticorruption) is supported by more than 200 leading corporations. It also publishes a globally recognized publication that ranks contributions that firms make in the area of social responsibility and ethical behavior: World’s Most Ethical Company (http://ethisphere.com/).

To aid in measuring social responsibility program progress, you can use a variety of performance metrics and indices (see Table 5.4). These can provide interesting information to guide results-oriented organizations to better levels of social responsibility performance.

Table 5.4. Social Responsibility Performance Metrics

Source: Adapted from ISM Web site: www.ism.ws/SR/content.cfm?ItemNumber=16738&navItemNumber=16739; www.ism.ws/SR/content.cfm?ItemNumber=4755&navItemNumber=5511. Retrieved on October 27, 2011.

The metrics in Table 5.4 measure what a firm has done after an effort has been made, but to really manage a social responsibility program requires an ongoing measurement of progress to direct and redirect efforts as needed. One way to do this is to install an auditing process to provide feedback to managers and individuals on how well they are doing in specific areas of social responsibility. Table 5.5 describes some of the more popular auditing methods for social responsibility.

Table 5.5. Social Responsibility Auditing Methodologies

Source: Adapted from ISM Web site: www.ism.ws/SR/content.cfm?ItemNumber=4755&navItemNumber=5511. Retrieved on October 27, 2011.

5.5. Other Social, Ethical, and Legal Topics

5.5.1. Legislation: California Transparency in Supply Chains Act

The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act requires companies to disclose the extent of their efforts to evaluate and address the risks of forced labor and human trafficking in their supply chains. This act was passed in 2010 and implemented in 2012 to address human-rights concerns regarding human trafficking. This legislation is based on fundamental social responsibility expectations for companies to assess and respond to adverse human rights impacts associated with their activities. It is further supported by the principles espoused by the United Nations (UN) in Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, approved by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011.

The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act is limited to firms doing business in California and that have annual gross receipts of (U.S.) $100 million. This also includes any retailer, regardless of corporate locations, whose sales in California exceed the lesser of $500, or 25% of total sales.

The act requires a listing on corporate Web sites that details the following:

• Efforts in evaluating and addressing risks of human trafficking and forced labor throughout the supply chain

• A statement from direct suppliers certifying materials incorporated into products comply with the act and other laws in the countries where they do business

• Efforts in conducting audits of suppliers to evaluate compliance with the act

• Efforts to maintain accountability standards and procedures for employees and contractors

• Efforts in training employees and managers on the mitigation of human trafficking and forced labor risk

Similar federal legislation is being planned, so it behooves all socially responsible supply chain managers to take implementation steps now. Altschuller (2011) suggests the following steps for supply chain organizations be implemented to comply with this legislation:

• Review supply chain risks related to forced labor and human trafficking (for example, related to products consumed, services used, supplier activities) to identify possible problem areas that need correcting.

• Review internal organization polices and standards for prohibiting forced labor and human trafficking to ensure compliance.

• Review external organization supply chain partners’ (upstream and downstream) organization polices and standards for prohibiting forced labor and human trafficking to ensure compliance.

• Review audit procedures to determine if independent social compliance audits are needed. This step should consider the nature and scope of the supply chain, risks of forced labor and human trafficking in partner operations, and whether existing auditing procedures are adequate to ensure compliance.

• Review accountability structures to ensure employees and partners are held accountable for compliance.

• Review training programs to ensure they are adequate to support compliance directives.

The requirements under this act for disclosure are specifically intended to provide consumers with the information they need to make purchase decisions related to these firms. For firms whose focus is on customer demand, exceptional efforts to comply with the act might lead to an exceptional customer competitive advantage.

5.5.2. Alternatives to Litigation

The undertaking of any contract involves risk taking. Most contracts and relationships between procurement staffers and suppliers run smoothly, but sometimes what takes place in those relationships creates legal issues that will involve legal remedies. Litigation is the most common method for resolving legal issues and is most suitable for multiparty disputes. Unfortunately, involving lawyers and courtroom time can be costly and may cause considerable damage to reputation and irreparable harm to business relationships. Making it worse, many contracts do not define dispute resolution procedures, complicating matters when problems do arise.

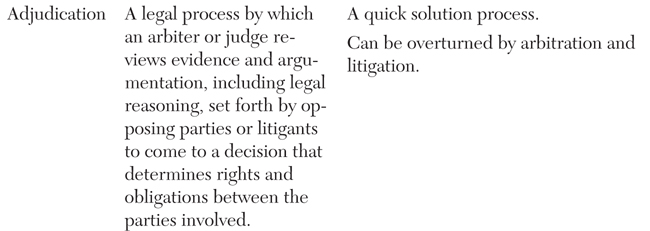

Suggested by Evans (2011) and others, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) processes such as mediation, arbitration, or adjudication provide effective alternatives to litigation (see Table 5.6). ADR processes are common in many countries, such as India, Australia, and the United States, which continue to provide leadership in their development and use.

Table 5.6. Alternative Dispute Resolution Methods

Source: Adapted from Evans (2011).

ADR enables both parties to preserve their commercial relationship while maintaining control during the process of dispute resolution. This keeps operations going despite these differences. Arbitration is particularly valuable with international contracts where parties are based in different countries, making legal judgments difficult to enforce. Arbitration is also conducted by someone with technical knowledge of the field and subject matter. For example, in international arbitration cases in London, arbitrators can be drawn from anywhere in the world and can be handpicked by the parties based on their experience and expertise. Also, arbitration can offer more flexibility than courts and in theory can be speedier, more efficient, and more cost-effective.

Mediation has grown tremendously in the past 15 to 20 years as a way of cutting through disputes. According to Evans (2011), it is a cheaper and quicker way of getting to a solution and has a greater than 80% settlement rate. This method also allows parties to reach an amicable agreement while maintaining ongoing relations. The focus of the process can be on the interests of the parties rather than on their legal rights alone so that other factors such as business pressures can be taken into account.

Adjudication, which is frequently used in the construction industry, is popular because it provides a quick answer. The resolver is likely to be a subject matter expert from the industry, such as an architect, surveyor, or engineer. The Construction Act of 1996 made the option of adjudication mandatory in construction contracts in the United States. Although it can be overturned by arbitration or litigation, it can also be a more economical solution because it minimizes disruption time to settlement in a long-term construction or project dispute, including supply chain project disputes.

The value of ADRs in supporting and building long-term relationships is an important critical success factor for procurement. By adding ADR to contracts, it sets up a framework that makes for more pleasant issue-resolution mechanism. Of course, for individual contracts, a dispute resolution clause has to fit in with the needs of the contract, which will differ greatly for different organizations.

Investment in dispute resolution does not have to be on a massive scale or expensive. For small contracts a focus on dispute-avoidance measures, as opposed to dispute resolution, can prove beneficial. These measures might include partnering or training staff in negotiation techniques. Partnering, for example, can be very formal and structured, forming part of an actual agreement that might include having a partnering coach and implementing team-building exercises. Alternatively, partnering can be merely agreeing to a positive early warning approach to managing the contract conflict. In summary, all of the ADR processes should be made available for the identification, investigation, and resolution of problems before they turn into disputes and before disputes turn into expensive litigation.

5.6. What’s Next?

According to Monczka and Petersen (2011), a growth strategy that commits to sustainability and corporate responsibility is the trend for the near future. They believe that the major drivers found in the survey they undertook include (1) it is the right thing to do, and consistent with a history of responsible citizenship, while also (2) meeting the expectations of customers, consumers, and other supply chain partners.

One of the difficulties in implementing a corporate responsibility program in a global context is trying to make it transparent enough for management to keep track of what is going on in the program (Arnseth, 2012a). The current trends appear to suggest that firms are presently and will increasingly step up in leadership roles to manage social responsibility programs, placing pressure on other firms to do the same. One example is IBM’s Global Supply Social and Environmental Management System (www.ibm.com/ibm/responsibility/report/2010/supply-chain/index.html). Under this system, the first-tier firms that do business with IBM are now required to establish and follow IBM’s management protocol system to address corporate and environmental responsibilities. IBM’s suppliers are now required to

• Define, implement, and maintain a management system that addresses corporate responsibility, including supplier conduct and environmental protection.

• Measure performance and establish voluntary, quantifiable environmental goals

• Be transparent by publicly disclosing results associated with these voluntary environmental goals and other environmental aspects of their management systems

As a part of the program, IBM also expects its first-tier suppliers to communicate these same requirements to their own suppliers that perform work on products and services supplied to IBM in an effort to expand the program globally. This sets an example for the current trends in ethics and social responsibility in supply chain management.