8. Negotiating

8.2 Guiding Principles in Negotiating Agreements

8.2.2 Negotiating Strategies and Tactics

8.3.1 Overcoming Negotiation Roadblocks

8.3.3 Preparing for Supply Chain Negotiations

Terms

Best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA)

Hardball strategy

Knowledge query manipulation language (KQML)

Least acceptable solution (LAS)

Maximum supportable solution (MSS)

Negotiation strategy worksheet

Particle swarm optimization (PSO)

Statement of work (SOW)

Third-party suppliers

Win-win strategy

8.1. Prerequisite Material

The various stages in the product life cycle for any product alters demand and in turn can change the relationships with suppliers. At each stage in the product life cycle, new contracts/agreements have to be negotiated or renegotiated because product demand has altered. This necessitates negotiation skills for anyone who hopes to have a supply chain management future.

On an esoteric level, negotiation is a dialogue between people or parties who seek to reach an understanding, resolve a point of difference, or gain advantage in producing an agreement upon courses of action that both parties will follow. Negotiation is intended to achieve a compromise between two parties, with each party trying to gain an advantage at the end of the dialogue process.

Supply chain negotiations commonly follow an advocacy approach, where a skilled negotiator serves as advocate for one party (for example, a purchaser) in negotiation to attempt to obtain the most favorable outcomes possible from the other party (for example, a supplier). (We use the purchaser and supplier relationship paradigm throughout this chapter.) In this negotiation process, the negotiator (which could be a lawyer, contracts specialist, purchasing agent, a business executive, or in complex situations, a whole teams of individuals) attempts to determine the outcomes that the other party (for example, supplier) is willing to accept, and then adjusts the purchaser’s demands accordingly. In this context, a successful negotiation occurs when the negotiator is able to obtain all or most of the outcomes his or her party desires. Negotiating is sometimes called win-lose strategy because of the assumption that one person’s gain results in another person’s loss. This is not true except in the most limited of negotiation situations, where participants are playing a zero-sum game (that is, what one gains, the other loses).

Table 8.1 describes a typical negotiation process as suggested by the Institute of Supply Management (ISM). As shown in Table 8.1, a great deal of analysis is needed for most any negotiation for the purchaser and the supplier to maximize their positions and to benefit their respective organizations. Like prepping for a debate, both parties must seek an outcome that achieves a winning compromise. Before the actual face-to-face negotiations take place, both parties should be positioned to know the needs of the other and what can be done to provide need satisfaction.

Table 8.1. ISM Overview of Negotiation Process

Source: Adapted from Carter and Choi (2008), pp. 149–183.

8.2. Guiding Principles in Negotiating Agreements

There are only two things important to supply chain managers in the theory of negotiation: what they want, and how to get it the way they want it. What purchasers want is a winning agreement with a supplier that serves their supply chain needs to their best advantage. Likewise, suppliers want a winning agreement to serve their needs. How to obtain an agreement for both parties involves knowing how to undertake negotiation using the right negotiating strategies and tactics.

8.2.1. Winning Agreements

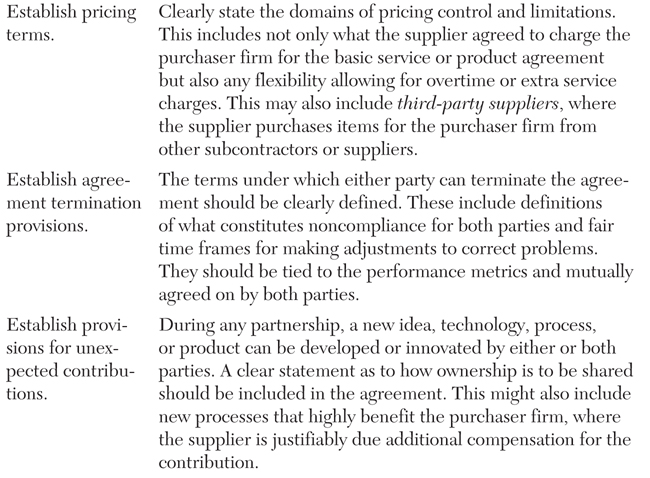

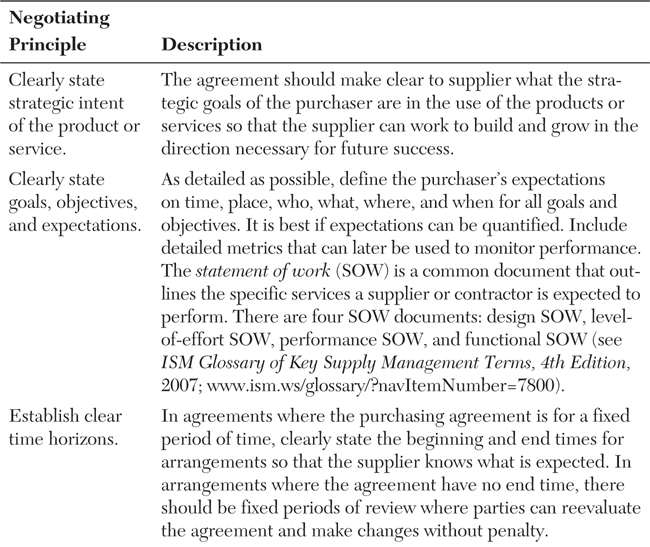

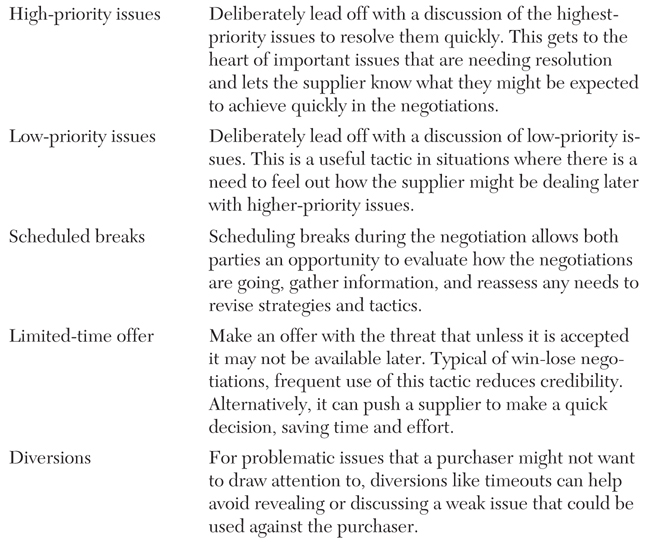

Winning agreements today are those that are transparent and detailed and provide a comprehensive statement of what both parties want and expect. There are many ways to achieve such agreements. The guidelines presented in Table 8.2 are a beginning framework to verse supply chain managers in the general content that should be included in the process of generating purchasing agreements.

Table 8.2. Principles in Guiding Content in Negotiating Purchasing Agreements

Source: Adapted from Schniederjans et al. (2005), pp. 62–63.

8.2.2. Negotiating Strategies and Tactics

Currently, supply chain management is moving too rapidly to waste time making agreements that may have little impact on a firm’s bottom line. That is not to say negotiation efforts of supply chain managers do not make major contributions to a firm’s bottom line; but long, protracted “game playing” is becoming an obsolete practice. However, some game playing might enable a purchaser to procure the best deal from a supplier. Old hardball practices (for example, “good guy, bad guy” or offering a “red herring”) will not lead to successful negotiations.

So, where does a winning negotiation strategy come from? It has been observed that some negotiators possess and use a particular style of negotiation. There are many styles a negotiator can adopt, and each has its own advantages and disadvantages (see Table 8.3). Understanding the differences in styles can help a supply chain manager identify underlying behavior that impacts agreement negotiations. For example, if supplier’s negotiating style is accommodating, the purchaser’s negotiator might be able to take advantage of this sensitivity to weaken or disrupt the negotiation process to the purchaser’s advantage.

Source: Adapted from Shell (2006), pp.112–145.

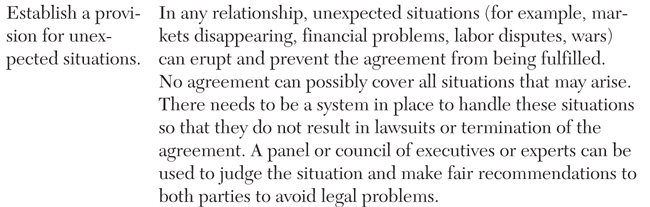

No one formula or single strategy can fit every situation in a negotiation process. The best advice for developing a winning strategy is to develop one that contains elements of criteria characteristic of winning strategies for negotiation. Table 8.4 describes a number of winning strategy criteria. As a check list, the suggestions in Table 8.4 can help supply chain managers avoid oversights in negotiation strategy development.

Table 8.4. Criteria for the Development of a Negotiating Strategy

Source: Adapted from Fawcett et al. (2007), pp. 361–368; Carter and Choi (2008), pp.178–181.

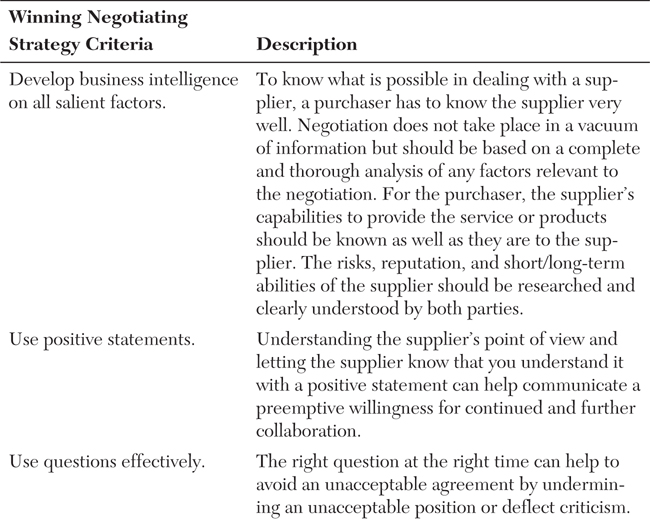

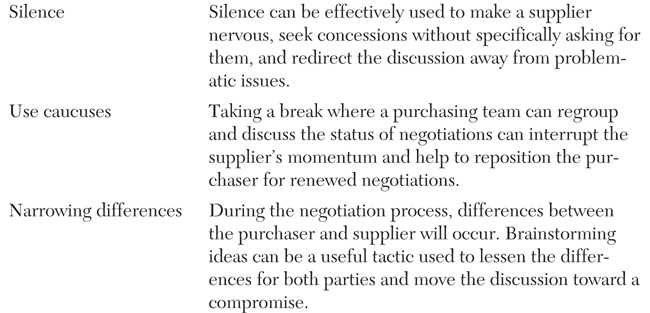

Once a general strategy is planned, tactics to help implement it are needed. Many different tactics can be used in a negotiation process. Table 8.5 describes some of the more commonly used tactics. Which ones you use depend on the preferences of the members on the negotiation team, the nature of the strategy selected, and the primary goals for the purchaser in the negotiation process.

Table 8.5. Common Negotiating Tactics

Source: Adapted from Fawcett et al. (2007), p.366; Carter and Choi (2008), pp.178-181.

8.2.3. Select Best Practices

In general, supply chain managers have found solace in a variety of best practices recommended by colleagues in industry. These best practices change over time. Robinson and Harkness (2011) suggest some best practices should be part of every negotiation strategy, no matter who is on the negotiating team or whether the team is negotiating for a product or a service:

• Silence is golden: Do not engage in outside communications with a supplier during ongoing negotiations. This does not violate the principle of transparency and openness. Some suppliers try to gain competitive information in outside communications that could be leveraged against the purchaser during contract negotiations.

• Maintain secrecy in approved budgets: Do not disclose information about approved budgets, nor about the internal vision for investing dollars in specific projects or whether a project is part of a key initiative or imperative for the purchasing organization. Information on any of these topics could indicate to a supplier that they have the upper hand and in turn could disadvantage the purchaser during negotiation discussions.

• Provide adequate timing: Allow the purchasing organization enough time to work through the negotiating process and communicate this is all parties. Business deadlines should not dictate negotiation strategy and execution.

Another important best practice concerns getting started in the negotiation process. In the beginning of any negotiating process, supply chain managers should maintain tight control over individuals taking part. Every participant should have a clear role and an intended purpose. All business organization staffers with a stake as internal customers should be included during strategy sessions as candidates for the negotiating team. Once the trusted potential members of a negotiating team are identified, supply chain mangers can then decide on the approach most beneficial for the assembled team. It is critical that all internal participants are in lock step with their roles. They should understand the ultimate strategy of the supply chain leaders in the negotiation process.

The outcome of the negotiation efforts is a final agreement that both parties agree on and that should benefit both. The amount of time and effort spent on negotiation of purchasing agreements is usually in direct proportion to the importance of the agreement to both parties. The suggestions offered in this chapter are a starting place and provide general guidelines for a negotiation process. Unfortunately, many issues can occur during the negotiation process and must be dealt with to have a successful agreement. Some of these issues are discussed in the next section.

8.3. Other Negotiation Topics

8.3.1. Overcoming Negotiation Roadblocks

Robinson and Harkness (2011) have suggested that when a planned negotiating strategy is not successful in reaching the desired result, bringing in executive leadership may be appropriate. Timing their entrance and understanding their roles are critical success factors in the use of this strategy.

Experienced or not, negotiators can usually tell when suppliers are stalling or when progress on issues is slowed or halted on purchasing agreement negotiations. Moving things along sometimes requires that negotiations move to the next level, in which the purchasing organization makes a declarative statement to show how serious it is about negotiation efforts. The strategy to break the stalemated process involves bringing in executive oversight. When a high-ranking executive is brought into the process, a clear message is sent to the supplier that the negotiation is strategic to the purchasing business. It can be an effective message communicating the purchasing organization’s desire for alignment and achieving an equitable solution for all parties. Negotiations usually take on increased attention when a high-ranking supply chain professional is engaged.

Once the high-ranking executive has decided to enter into the negotiation process, it is important that the strategic role of the executive be clearly defined, as is the case for the entire negotiating team. The executive’s role, according to Robinson and Harkness (2011), should be confined to when an agreement is nearly complete or when there is a stalemate that can be broken only by discussing or changing internal policy. For example, in an agreement close to completion there may be a few final high-level items that must be incorporated as part of the contract. Robinson and Harkness suggest that is when it is appropriate for an executive to step in. If the executive decides the proposed conditions are met, the negotiated agreement can be finalized.

Robinson and Harkness also suggest that it is critically important that once the supply chain executive is engaged, he or she should not disengage, because the negotiation team will appear weaker if the leader leaves the proceedings for any reason. An executive disengaging or stepping back from negotiations may be interpreted by the supplier that that particular executive is the decision maker who will need to be consulted prior to negotiations being finalized. This may be perceived by the supplier as reduced roles for the rest of the purchaser’s team, and in turn, may diminish the team’s ability to conclude the negotiation.

Bringing an executive into the negotiation process should always be accomplished in a precise manner to achieve a very specific goal. Because the negotiating process changes when a supply chain executive steps into the proceedings, executives should follow two key guidelines to direct negotiating tactics:

• Focus on problem solving in negotiating: This requires an executive to focus on the larger issues, such as long-term strategic vision, research and design initiatives, and collaborative long-term strategic partnerships. Avoid smaller issues that tend to only diminish the executive’s standing in the eyes of the opposing party.

• Learn from the supply management team: Before stepping into the negotiating arena, the supply chain executive should gain a full understanding of key challenges and the competitive landscape of the negotiation.

Executive-level support in the negotiating process can help supply chain organizations navigate the difficult negotiations and execute a successful agreement for all parties. A high-ranking executive, when engaged at the right moment with a clear and defined role, can be a catalyst to help negotiators arrive at a successful purchasing agreement.

8.3.2. Delaying Tactics

Stalling, according to Jensen (2011), is usually employed as a tactic to inspire uneasiness and doubt in an opponent. Stalling can also be used more ethically to buy time in situations where additional research or internal discussion is needed and also if the negotiator is worried about emotions bleeding into the work (that is, gives them time to cool off).

Like any delaying approach, there are risks in using this negotiation tactic. A supplier, for example, might read a sudden absence of communication or a delaying change in discussion as being combative. The effects of a delay may end up placing the purchasing team under even more pressure instead of buying more time. Indeed, a supplier feeling neglected might simply decide to withdraw the offer.

How can we know whether a supplier is stalling? There are several ways. For example, being asked to look at further documentation when all the necessary information to begin negotiation is already present may be a stalling tactic. Similarly, if a supplier’s negotiation team suddenly decides they are not qualified to negotiate, that may be a stalling tactic. In addition, always be on the lookout for the same questions or ideas being recycled.

The best practical way to deal with this is to use the same tactic. Jensen (2012) suggests taking the time the supplier negotiator provides by his or her absence and using it to the purchaser’s advantage. The extra time may be spent on analysis of the supplier to be better prepared when the supplier finally decides to return to negotiate again. The ideal option is to circumvent the situation altogether by setting timetables and deadlines at the outset. If the purchasing team expects stalling tactics from the supplier, they should make sure the supplier understands right off what is expected as far as scheduling is concerned.

Finally, purchasers should be aware that some supplier negotiators stall not as a ploy, but as a defense mechanism. If a negotiator does not appear to want to make up his or her mind, or uses overly formal language or obscure procedural issues, it might be to simply scale things back or take things slower.

8.3.3. Preparing for Supply Chain Negotiations

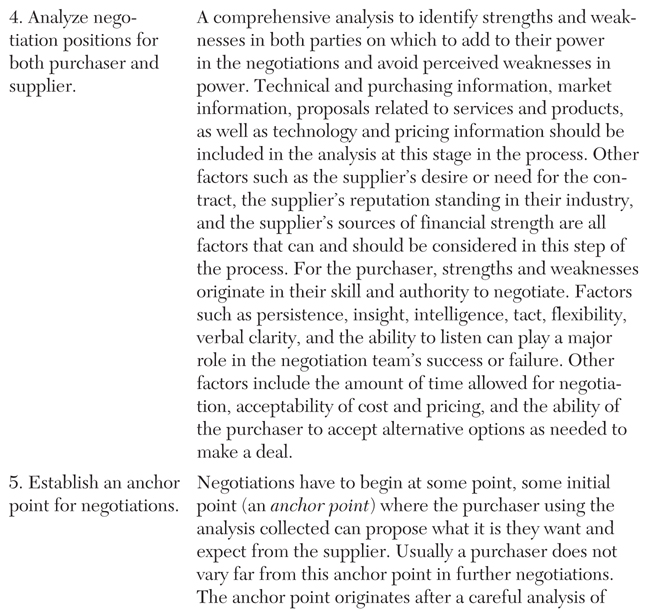

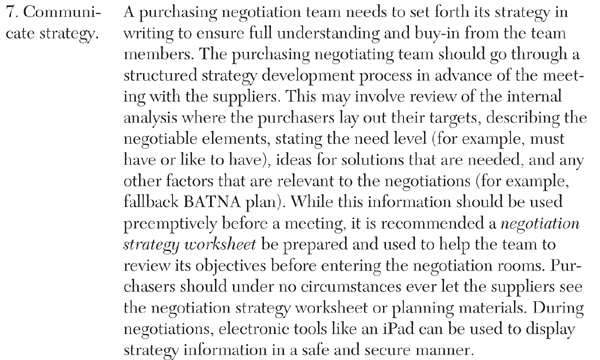

It is essential for purchasing teams to craft a clear strategy for the negotiation. This strategy should formalize the objectives to be addressed with the supplier negotiating team. It should also help to identify acceptable ranges of solutions for each negotiable element such as the maximum supportable solution (MSS) and least acceptable solution (LAS), as well as to clearly identify the best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA) or fallback plan in the event that the negotiation is not successful. Developing the strategy is essential to the preparation work needed to enter purchaser/supplier negotiations. Negotiation experts recommend 75% of the total time spent in the negotiation process should be spent in preparation activities. These preparation activities should include data collection and analysis of suppliers and strategy development and education of the purchaser’s negotiation team. Unfortunately, the levels of preparation of the typical supplier negotiating team is substantially greater compared to their purchasing opponents.

According to Trowbridge (2012), a number of proven steps can be followed to prepare negotiators for even the most complex negotiations with suppliers, as described in Table 8.6.

Table 8.6. Winning Negotiation Preparation Steps

Source: Adapted from Trowbridge (2012), pp. 46–51.

8.4. What’s Next?

Many advances in negotiation theory are continuously appearing in the academic literature. Many of these advances are behaviorally theoretical and do not have much application for many years to come because of their unproven, theoretical nature. One area of development in the trend of negotiation practice is the use of automated technologies to augment and conduct negotiations.

As Ito et al. (2012) illustrate, technology can be used for active negotiations by permitting (or not permitting) revelation of information for decision making. An important and emerging area in the field of negotiation is the use of autonomous agents (that is, software that is at least partially autonomous) and multi-agent systems (that is, MAS composed of intelligent agents that are software applications with algorithmic and other procedural programming). MAS actually has the ability to share information using knowledge query manipulation language (KQML) (a software programming language to search for answers to queries). Autonomous agents and MAS can self-organize and self-steer efforts to control negotiation paradigms operating without human intervention. Autonomous agents can support automation or simulation of complex negotiations and can provide efficient bargaining strategies. To achieve such complex, automated negotiation, advances in artificial intelligence (AI) technologies (that is, logic and mathematical algorithms), genetic algorithm (GA) (that is, a search heuristic that mimics the process of natural evolution), and a particle swarm optimization (PSO) (that is, a computational method that optimizes a given solution through iterative steps) can be used.