6. Sustainable Supply Chains

6.2 Managing Sustainable Supply Chains

6.2.1 Reasons for Sustainability

6.2.2 Implementing a Sustainability Program

6.2.3 Barriers That Hinder Implementation of Sustainability

6.3 A Model for Sustainability

6.4 Other Topics in Sustainability

6.4.1 Strategy for Achieving a Green Supply Chain

6.4.2 How to Begin Sustainability

6.4.3 Factors to Build on for Sustainability

6.4.4 Measuring Sustainability

Terms

Chief sustainability officers (CSO)

Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes

E-freight initiative

Emergy sustainability index (ESI)

Institute of Supply Management (ISM)

International Air Transport Association’s (IATA)

International Standards Organization (ISO)

Production and Operations Management Society (POMS)

Supplier sustainability scorecard

6.1. Prerequisite Material

A growing philosophy of business has emerged in the past couple of decades that suggests firms should undertake responsible stewardship of capital, ecological, and human resources used in the production and delivery of goods to customers. The philosophy, referred to as sustainability, denotes that firms should meet humanity’s needs without harming future generations (Christopher, 2011, p. 241). Sustainability is often referred to in a more colorful fashion as green initiatives or greening the organization. Supply chain sustainability means working with upstream suppliers and downstream distributors and customers to analyze internal operations and processes in order to identify opportunities to find alternative, environmentally friendly ways of producing and delivering products and services (Mollenkopf and Tate, 2011). It also means extending stewardship across products’ multiple life cycles to include all phases from development and introduction to final decline in demand and disposal. Krajewski et al. (2013, pp. 442–443) suggest that sustainability involves thee basic elements: financial responsibility, environmental responsibility, and social responsibility. As shown in Table 6.1, supply chain managers can make contributions in each of these three areas.

Table 6.1. Sustainability Elements

Source: Adapted from Krajewski et al. (2013), pp. 442–443.

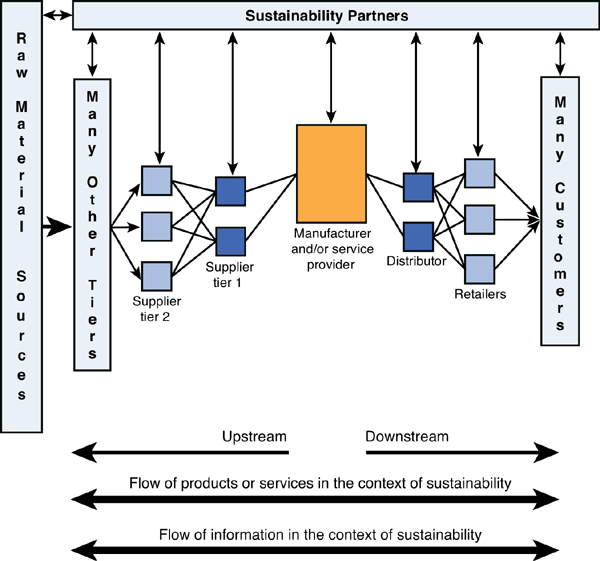

While some firms initiate greening their operations at an operational level (for example, reducing spoilage, remanufacturing old stock into new) many firms are recognizing and implementing sustainability as a strategic imperative. For a manufacturer or service organization, this may entail bringing many supply chain partners into a collaborative arrangement to work together to achieve sustainability throughout the entire supply chain. This collaboration alters more traditional supply chain product and information flows. Comparing the traditional supply chain Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1, “Developing Supply Chain Strategies,” with the sustainability revised version in Figure 6.1, product and information flows now move forward and backward, up and down the supply chain. Customers, for example, may be asked to return products for disposal, particularly those that may pose an environmental hazard (for example, lead in batteries, products with poison components). As depicted in Figure 6.1, the ideal strategy to achieve sustainability includes all supply chain partners sharing information and products as needed.

Figure 6.1. Supply chain network in the context of sustainability

Source: Adapted from Figure 5.1 in Schniederjans and Olson (1999), p. 70.

6.2. Managing Sustainable Supply Chains

6.2.1. Reasons for Sustainability

To manage programs well requires understanding and agreement with the reasons for their existence. What drives sustainability and green initiatives in organizations can actually benefit all supply chain partners. Mollenkopf and Tate (2011) suggest there are at least three reasons why firms embark on sustainability as a strategy, as follows:

• Risk management: Risk management involves reducing risk in all areas of a business. Such as identifying operations in business that may pose a later financial risk to a firm (for example, using toxic or hazardous materials in the production of products that may result in law suits against the company in the future) and reducing or eliminating those risks. (Risk management is an important subject that will be dealt with in Chapter 11, Risk Management.”)

• Government regulation: Without U.S. federal regulations, automobiles would not have seatbelts to protect people, catalytic converters to reduce air pollution, increased automobile mileage to save the Earth’s resources, and many other features that are commonplace today. By anticipating government regulation, many firms implement green initiates well ahead of government dictates and have found that resources can be saved in the long run, which more than compensates for the costs of the initial changes in operating systems. Indeed, recycling efforts can generate profits for organizations (Kuhn, 2012).

• Supply chain influence: Customers expect firms to have a friendly environmental record that provides environmental consideration in product requirements (for example, less packaging waste) and to make investments in sustainability in their facilities. Customers and other supply chain partners have a vested interest in both cost and environmental savings. Supply chain partners in one area of a supply chain can influence other partners to increase participation in sustainability programs. Most firms today embrace and comply with various International Standards Organization (ISO) guidelines to be competitive and in many cases as a requirement to do business. According to Mollenkopf and Tate (2011), customers seek suppliers who are environmentally responsible by using the ISO 14001 certification as a part of the selection criteria. In fact, there are four aspects of a sustainable relationship in the ISO 14001 guidelines: (1) awareness of a company’s impact on the environment, (2) acceptance of responsibility for those impacts, (3) the expectation that harmful impacts will be reduced or eliminated, and (4) assignment of responsibility for environmental impacts (Haklik, 2012).

6.2.2. Implementing a Sustainability Program

There are as many different ways to launch a sustainability program as there are differing programs. To initiate one, a firm can simply identify where environmental and social-responsibility problems or opportunities exist internally within its manufacturing facilities and then expand to include the entire supply chain. In each case, an evaluation of alternative environmentally friendly ways to make improvements should be undertaken. This can be done by mapping the internal production/service processes and expanding to the external supply chain functions. Careful consideration of economic and social tradeoffs should be used to select the most desirable course of action. Once a course of action is selected and implemented, continual measurement of performance is needed to ensure that the program is achieving the right balance of environmental and social considerations.

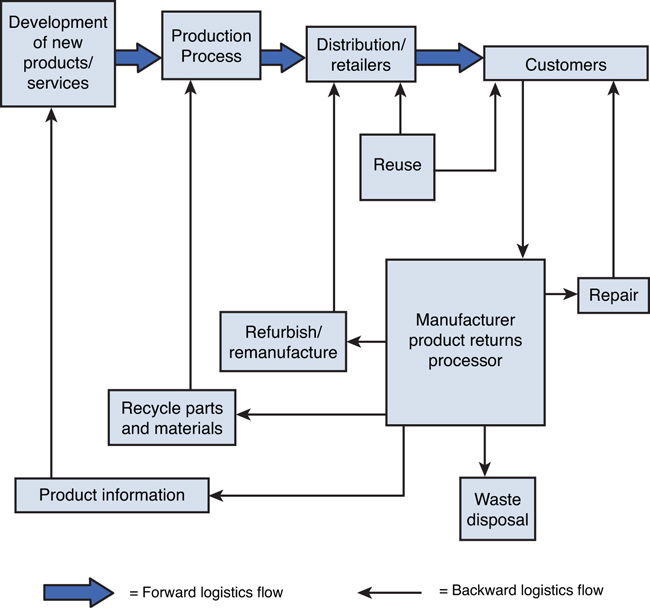

A reverse-logistics program is an example of a sustainability program. Reverse logistics is a process of planning, implementing, and controlling the efficient, cost-effective flow of products, materials, and information from the point of consumption back to the point of manufacturing or origins for returns, repair, remanufacture, or recycling (Krajewski et al., 2012, p. 444). Krajewski et al. (2012, pp. 444–445) suggest that supply chains can be designed to be environmentally responsible if they plan for the entire life cycle of a product. This can be a closed-loop approach of planning that considers all processing possibilities from the product’s creation to its final waste removal. An illustration of many of the features that can be used in a sustainable program are included in a combined forward and reverse logistics supply chain (see Figure 6.2). How many iterations a product or its parts may undertake in this closed-loop system will depend on a number of factors in addition to the product and participation of all the supply chain partners.

Figure 6.2. Sustainability closed-loop supply chain

Source: Adapted from Figure 13.2 in Krajewski et al. (2013), p. 445.

6.2.3. Barriers That Hinder Implementation of Sustainability

Mollenkopf and Tate (2011) have suggested several commonly occurring hindrances to sustainability programs, as follows:

• Financial costs: The upfront investments in waste reduction and reengineering products to be more ecologically friendly may in some industries be so substantial that firms might back away from any sustainability initiatives. This is a short-term view and often does not include consideration of longer-term benefits of such programs. Sustainability programs should be planned and analyzed in the context of the longer-term product’s life cycle. Computer manufacturers have found that remanufacturing and recycling older computer components can generate substantial profits while saving the environment.

• Corporate structure and culture: As mentioned in previous chapters, functional silos can be an inhibiting factor to any kind of change such as programs of sustainability. It is recommended that coordinating a firm’s internal structure, perhaps making it flatter and without the focus on functionality, should be a precursor to considering sustainability programs.

• Supply chain influence: If customers are unwilling to pay the extra costs for implementing a green initiative, resistance to sustainability can be substantial for the customer-focused supply chain. It is recommended that firms educate customers as to the benefits and tradeoffs of environmentally friendly products and services to overcome this hindrance.

• Products and processes: The nature of products, their design and contents, as well as the processes used to produce them can conflict with environmental goals in the areas of energy consumption and product durability. Products should be made so that they are more easily recyclable. Considering the entire life cycle of a product when it is being designed makes it easier to plan for both its use and reuse in a recycling environment.

• Communication issues: Inconsistent terminology and definitions of what sustainability means causes translation problems. Without clear definitions of effective measures and communications about environmental issues, it can be confusing. Without easy-to-measure and understandable performance information on the progress of a sustainability program, it is difficult to control and can lead to program failure. Developing a set of understandable terms and metrics of what green means to the firm will help participants throughout the supply chain be more effective in achieving sustainable goals.

6.3. A Model for Sustainability

In a review of multiple survey research studies, Nirenburg (2012) found a number of commonalities in supply chain practices that, when taken together, can constitute a model for sustainability. Based in part on a similar discussion presented in the preceding section, Nirenburg (2012) found a combination of three components (drivers, barriers, and enablers) forms a framework for a typical firm’s sustainability supply management program. As presented in Figure 6.3, the combination of those three components will eventually lead to a variety of benefits described in the literature.

Figure 6.3. Model for sustainability

Source: Adapted from Figure in Nirenburg (2012), p. 30.

The review of research studies reveals other sustainability drivers beyond cost minimization, including pressure from employees, commitment of the founder, and championing from senior management. Barriers include cost of the program, a gap of employee skills and knowledge to implement and run a program, lack of measurement and reporting, as well as a lack of consistent standards and their implementation. Enablers are also identified in the literature that contribute to developing a successful sustainability program, including partnering with suppliers characterized as being close and cooperative, trusting, and ones that maintain transparent communications, establish effective supplier evaluation systems with rewards and penalties, use cross-functional teams, and collaborate in areas of innovation and process improvement.

To utilize this model to implement a sustainability program, Nirenburg (2012) suggests the following steps:

1. Identify sustainability champions:Regardless of who they are and in what level in the organization they reside, use them to motivate and move the program forward.

2. Conduct a self-audit of drivers:Particular issues that drive sustainability, are the best candidates to focus on and be strengthened in order to justify the program and support buying into it.

3. Find ways to mitigate barriers:Identify barriers and explore the organization for a means to counter or overcome any potential factors that act as barriers to a sustainable program.

4. Utilize other enablers:Identify any possible enabler to operationalize and maximize the outcome of a sustainable program.

The model presented in this section is a general framework for establishing criteria under which a sustainability program can be initiated. Other additional considerations have to be built in to it to ensure success now and in the longer term. Some of these topics are addressed in the following section.

6.4. Other Topics in Sustainability

6.4.1. Strategy for Achieving a Green Supply Chain

Logistics and green supply chain sustainability involve many elements, from packaging to processing time. For supply chains, time is money, and the fastest modes of distribution, particularly air transport and expedited ground freight delivery, often require the most energy-intensive efforts to serve customers. Manufacturing just-in-time modes of production are an additional requirement for speed often at the expense of energy consumption. How then does a logistics operation increase speed of delivery without a substantial cost of increased fuel usage? According to Kaye (2011), the best way to achieve a favorable balance in speed of delivery and fuel usage is by wringing out inefficient and wasteful logistics practices. Issues such as information snags, incomplete or missing data about the status of shipments, an inability to retrieve data when needed, an inability to adequately document shipment status, ill-prepared shipping documents, and inappropriate cargo routing can create huge and unnecessary waste of fuel, requiring expedited and energy-inefficient delivery to overcome delays. If you have ever seen a truck driver whose engine is running while waiting for a delivery paper to be signed, you know what wasted fuel can occur when a snag in paperwork happens.

To overcome these informational issues Kaye (2011) suggests that a supply chain founded on green principles must have comprehensive information on everything from fuel efficiency to aggregating and optimizing loads and routes that aid in the planning, which reduces the fuel consumption and carbon footprint of shippers. This information can facilitate up-to-the-minute route and load scheduling to take into account everything from weather conditions to just-in-time shipment adjustments. Taking these conditions into consideration can help avoid wasted logistic efforts when weather and other conditions cause costly delays. Starting with suppliers through the supply chain to the customer, products should be monitored using electronic tracking systems. This could involve creation of complete databases that show what is happening at every step in the supply chain. This necessitates electronic connectivity between producer, shipper, and forwarder to provide an ability to cross-check and validate progress and timings of shipments.

By using cutting-edge electronic tracking systems, manufacturers can ensure deliveries are on time and maintain proper quality. This improves both fuel efficiency and cost-effectiveness because it creates absolute shipment control at any given time. Other benefits of electronic tracking include elimination of inefficiency from physical keying or writing of routing and freight identification numbers and mistakes that force wasteful backtracking and searches.

Kaye (2011) reports that the International Air Transport Association’s (IATA) e-freight initiative directly addresses the idea of minimizing documentation issues that waste fuel and other resources. The IATA e-freight project aims to replace 20 standard paper shipping documents with electronic documentation. The estimated result is a savings of up to $5 billion a year for the logistics industry in reduced paperwork and faster transit times, because sending shipment documentation electronically before the cargo itself arrives can reduce cycle time by an average of 24 hours (Kaye, 2011). If implemented by the industry, this initiative will eliminate the guesswork and backtracking to find misplaced shipments and affords maximum flexibility in route and load planning to minimize energy consumption and delivery problems. In turn, by saving fuel, energy, resources, and time, supply chain sustainability, based on the latest electronic technology, will give participants competitive advantages while minimizing the ecological footprint.

6.4.2. How to Begin Sustainability

According to Polansky (2012), sustainability initiatives should start by working with key suppliers to uncover ways to enhance supply chain operations and reduce the environmental footprint. These may include purchasing energy-efficient products or reducing packaging waste to increasing the percentage of purchased products made from recycled materials. Then, a list of key suppliers from major purchasing commodity groups who are willing to support sustainability initiatives should be developed. For example, at the plant level, plumbers may be able to suggest new plumbing fixtures that will save water, or local electric companies might suggest ways to reduce electricity usage. Internally, marketing and engineering departments might suggest ways to package products to avoid waste.

Once the sustainability ideas are suggested and converted into goals, supply partners should be selected that support these goals. This selection process should be based on a willingness to participate and offer suggestions to further support the organization’s sustainability goals.

Polansky (2012), suggests that once well-defined goals are in place and the suppliers that will be included in the sustainability initiative are identified the firm should consider developing a supplier sustainability scorecard to measure performance based on sustainability criteria (see Kuhn, 2009). These scorecards can be assessed based on subject criteria (for example, sustainable idea innovations) or objective criteria (for example, reduction in cost of packaging). Creation of a scorecard gives both the purchasing group and the supplier a way to identify, track, and measure activities considered important for achieving a company’s sustainability goals.

Invariably, the issue of price versus value comes up in any procurement program. Normally, price would weigh heavily on the supplier decision, but not so when considering a sustainability program. In a sustainable supply chain, this relationship is still important, but the weight is heavier toward longer-term considerations, such as energy saving offsets, tax incentives, life cycle and maintenance costs, reduced disposal costs, reduced waste, and productivity improvements.

As is the case with sustainability programs, higher upfront costs need to be understood by all partners. The best way to deal with the issues that will emerge from this cost fact of is to provide information to make defend green decisions. Polansky (2012) suggests procurement professionals should fully discuss any questions regarding cost-benefit analyses, life cycle costs, and recycling options with their key suppliers. Suppliers will need to know and be able to explain their products and life cycle costs. By probing suppliers for more cost and environmental options information, procurement managers will gain better insight into the bottom-line impact of sustainable purchasing, as well as potential better insight into impacts on product obsolescence, hazardous-material handling, and overall waste reduction. During these discussions, procurement professionals are more likely to identify suppliers that can work with them to genuinely implement green solutions. These suppliers can also help identify and prioritize green operational projects.

Supply professionals should also ask about internal green practices or programs that partners have undertaken. Working with suppliers who have implemented sustainable strategies helps ensure that suppliers have an understanding about the customers’ needs. Finally, it will be beneficial to look for industry involvement, such as a firm being a member of the U.S. Green Building Council, a Washington, D.C.-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization committed to a prosperous and sustainable future through cost-efficient and energy-saving green buildings (www.usgbc.org/DisplayPage.aspx?CMSPageID=124) or having certification with Energy Star, a joint program of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Department of Energy helping to save money and protect the environment through energy efficient products and practices (www.energystar.gov/index.cfm?c=cbd_guidebook.cbd_guidebook_apply_3). Suppliers that have made investments in organizations like these validate their own sustainability position and tend to keep up with the latest industry information.

In summary, identifying appropriate partners and establishing key action items are helpful first steps in building an effective sustainable supply chain. What can result is a close collaboration that benefits all. Once procurement managers have a sense of how their suppliers can help, they can begin to create solutions that make sense for their business (Polansky, 2012).

6.4.3. Factors to Build on for Sustainability

Slaybaugh (2010), reporting on a larger study by the Boston-based Aberdeen Group “Sustainable Production: Good for the Plant, Good for the Planet,” explored the status of sustainability intentions of more than 230 enterprise initiatives. Among the enterprises surveyed, clues as to the best-in-class that were making measurable steps toward sustainable production were identified. They found the best-in-class performers averaged over 80% with regard to equipment effectiveness (that is, a composite metric accounting for availability, performance, and quality), over 20% in energy-consumption reduction, at least 30% reduction in emissions versus the previous year (as measured by the year-over-year change in emissions controlled for year-over-year changes in production output normalized by energy intensity of the production processes), and almost 20% outperformance of corporate operating margin goals. In addition, best-in-class manufacturers were three times as likely to have appointed a chief sustainability officer.

The Aberdeen Group study also identified what firms could do to become best-in-class performers. They found four primary guiding principles contributed to the best-in-class performers:

• Seek visibility into energy and emissions data by investing in energy management and environmental management solutions. For example, establish a corporate supply chain management responsibility team as Del Monte did, consisting of vice president and director-level executives across functional teams. The company is also planning green plant teams made up of plant-floor employees.

• Seek to clearly outline the company’s sustainability programs. The best-in-class companies are more likely to have standardized business processes in place across three major initiatives of sustainability: energy, environment, and safety.

• Seek to install a framework of data collection to support sustainability. The best-in-class performers are more likely to automatically collect energy data and store it in a central location. For example, Del Monte invested in a solution that collects information regarding sustainability programs every month and then compares it with the company’s baseline year.

• Seek to establish an executive leadership framework. Successful sustainability initiatives require executive leadership support. Best-in-class organizations were found to be much more likely to have chief sustainability officers (CSOs) in place to execute, drive, and have responsibility for the success of initiatives.

6.4.4. Measuring Sustainability

A 2011 survey reported by ProPurchaser.com (www.propurchaser.com/green_supply-chain.html) examined the greening of production operations. They found a greener supply chain was definitely preferred, but it appeared measurement tools were lacking to aid these initiatives. Over 80% of the supply chain professionals in the survey responded by saying they would favor suppliers with green business practices, but only 25% had any type of carbon footprint evaluation process in place. To fill this gap, supply chain organizations like the Institute of Supply Management (ISM) have developed a variety of indices and metrics useful for measuring sustainability. ISM incorporates corporate social responsibility with sustainability. The Institute of Supply Management’s (2012) educational guidelines suggest the following indices might serve as useful measuring tools:

• ASPI Eurozone (Advanced Sustainable Performance Indices) is the European index of companies and investors wishing to commit themselves in favor of sustainable development and corporate social responsibility based on 120 best-rated companies in the Eurozone.

• Dow Jones Sustainability Indexes are the first global indexes to track the financial performance of leading sustainability-driven companies worldwide. They provide asset managers with reliable and objective benchmarks to manage sustainability portfolios.

The ISM also suggests practitioners consider impact, influence, and positioning when selecting and developing metrics. ISM developed a listi of areas for possible metric applications, including the following:

• Supplier qualification and certification decisions

• Product design, redesign, and statements of work

• Training to ensure understanding of decisions related to sourcing, recycling, and so forth

• Internal development, quantification, and basing decisions on financial and other risks related to nonconformance with or lack of support of sustainability initiatives

• Recordkeeping status on corporate sustainability reporting

• Measurement, tracking, and reporting mechanisms embedded at the worker level

• Implementation of end-of-life product management policies and procedures internally and with suppliers

In addition, ISM recommends senior management be engaged across the organization to ensure appropriate governance structures are in place; they also suggest making the CSO’s contact information publicly available. It is also suggested that periodic reports on sustainability be released internally and in the marketplace to permit further transparency of sustainability activities.

Beyond guidelines for sustainability, there are a variety of quantitative ways to measure it. A theoretical approach has been offered by Brown and Ulgiati (1999), who published their formulation of a quantitative sustainability index (SI). This index is a ratio of the emergy (spelled with an m, that is embodied energy, not simply energy) yield ratio (EYR) to the environmental loading ratio (ELR):

Called the sustainability index, the Emergy Sustainability Index (ESI) accounts for yield, renewability, and environmental load. “It is the incremental emergy yield compared to the environmental load.”

Many quantitative metrics for sustainability consist of very simple measures:

• Percent purchases from sustainable sources

• Percent of waste diverted from landfills

• Energy reduction caused by greening a building

• Recycling rates as a percent of total waste

• Percent of suppliers undertaking sustainable programs

• Percent of scape waste reduction

• Dollar investment in sustainability training, programs, initiatives, etc.

Many additional sources of information on sustainability and how to measure it are available:

• Green Office Guide: www.greenbiz.com/toolbox/reports_third.cfm/LinkAdvID=22121 www.greenerchoices.org/eco-labels

• Responsible Purchasing Network www.responsiblepurchasing.org www.energystar.gov/

• US Green Building Council www.usgbc.org

• Center for a New American Dream www.newdream.org/procure

• For specific chemicals and alternatives:Inform (www.informinc.org)Green Seal (www.greenseal.org)Scorecard (www.scorecard.org/chemical-profiles/index.tcl_)

6.5. What’s Next?

Not all firms view sustainability as critical, but it appears they will in years ahead. According to a survey of more than 700 CEOs of major corporations, over 90% believe sustainability issues are critical to future success (“A New Era...,” 2010). Almost 90% of the CEOs believe they should integrate sustainability throughout their supply chains, but only 50% believe they can achieve such integration. The gap between these percentages reflects the anticipated difficulty in selling sustainability to supply chain organizations. Regardless, the present trend for sustainability programs is one of growth. According to CAPS Research, whose findings are translated into guidance for senior supply chain managers, environmentally sustainability supply chains are necessary to deliver future value and performance improvements (Monczka and Petersen, 2011). A further institutionalization of sustainability is reflected in academic organizations such as the Production and Operations Management Society (POMS), which has created the College of Sustainable Operations. This college holds annual meetings on sustainability, developing curriculums and other educational support for this subject. Many other organizations are devoted to sustainability. Some of the more common Web sites for organizations devoted to sustainability in business includes the Business of a Better World (www.bsr.org/), Network for Business Innovation and Sustainability (http://nbis.org/about-nbis/profitable-sustainability/), and GreenBiz.com (www.greenbiz.com/section/business-operations).